Articles

Sky Gilbert, Daniel MacIvor, and The Man In The Vancouver Hotel Room:

Queer Gossip, Community Narrative, and Theatre History1

Abstract

This essay outlines how the gossip surrounding Tennessee Williams’s visit to Vancouver in 1980 has influenced the narratives of gay communities and in so doing contributed to queer theatre history in Canada. Stories of Williams inviting young men to his hotel room and asking them to read from the Bible inspired Sky Gilbert and Daniel MacIvor to each write a play based on these events. The essay argues that Gilbert and MacIvor transcend the localized specificity of the initial rumours and deploy gossip as a tool to articulate a process of sexual and cultural marginalization, thereby fostering a dialogue with the past. This dialogue marks a crucial and pedagogical task in gay and queer theatre to address the on-going needs of an ever-changing community.

Resume

Dans cet article, Dirk Gindt montre comment les rumeurs qui ont entouré la visite de Tennessee Williams à Vancouver en 1980 ont façonné les récits des communautés gais et, ce faisant, ont contribué à l’histoire du théâtre queer au Canada. Après avoir entendu dire que Williams avait invité des jeunes hommes à monter à sa chambre d’hôtel pour ensuite leur demander de lui lire des passages de la Bible, Sky Gilbert et Daniel MacIvor ont chacun été inspirés à écrire une pièce à partir de ces événements. Gindt fait valoir que Gilbert et MacIvor transcendent l’origine spécifique des premières rumeurs et les utilisent pour exprimer un processus de marginalisation sexuelle et culturelle. Ce faisant, ils favorisent un dialogue avec le passé qui constitue une tâche essentielle et pédagogique du théâtre gai et queer qui veut adresser les besoins continus d’une communauté en constante évolution.

-Nick Salvato, “Editorial Comment: The Age of Gossipdom”

1 In the fall of 1980 Tennessee Williams was offered the prestigious appointment of Distinguished Writer in Residence at the University of British Columbia. Although the pressures of giving multiple university lectures soon overwhelmed him, Williams’s time in Canada was made significantly more attractive by the Vancouver Playhouse, which was preparing to stage a new version of his play The Red Devil Battery Sign. Directed by Roger Hodgman, the revised and considerably shortened version of Red Devil ran for a month. Reviews were mixed and the production proved as unsuccessful as previous attempts in Boston (1975), Vienna (1976), and London (1977). 2 While Red Devil failed to make a lasting impression on Canadian audiences and critics, the legacy of Williams’s visit inspired a number of colourful stories, some of which paint an unflattering picture of the playwright. On one occasion he apparently gave an endless, alcohol-inspired rendition of “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina” at a party; on another night he lost one of his socks in a restaurant; and during a preview of Red Devil he proceeded to fall asleep (Lederman R1). However, several people who met Williams at the time have shared their fond memories of him. Among others, these include a volunteer at Vancouver’s gay TV station, GaybleVision, who interviewed the famous visitor (Rowe) and a second young man, an aspiring playwright, who received a letter of encouragement from Williams (Emberly). The Artistic Director of the Vancouver Playhouse recalled that Williams was “the easiest writer I’ve ever worked with” (qtd. in Page 94), and one of the actors in Red Devil remembered how Williams, despite some occasionally odd behaviour and comments, “was great in rehearsal, [. . .] very funny and charming” (qtd. in Lederman R1) and willing to rewrite dialogue that did not work. One story in particular, however, has had a significant impact on English-Canadian theatre history. This story recalls how, on several occasions, Williams invited young men to his hotel room and asked them to read from the Bible in nothing but their underwear. Told and re-told countless times in queer circles, this story would eventually inspire two playwrights to write plays based on Williams’s 1980 stay in Vancouver: My Night with Tennessee by Sky Gilbert (first produced at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre in Toronto in 1992) and His Greatness by Daniel MacIvor (first produced at the Arts Club Theatre in Vancouver in 2007).

2 While Williams’s influence on American playwrights is well- documented (see Kolin) and Louise Ladouceur has outlined his impact on Quebec theatre, 3 this essay attends to Williams’s legacy on English queer theatre north of the 49 th parallel. I specifically reflect on how the gossip surrounding the playwright’s visit to Vancouver has influenced the narratives of gay communities and in so doing contributed to queer theatre history in Canada. I argue that Gilbert and MacIvor, influenced by their respective agendas, transcend the localized specificity of the initial piece of gossip to convey more general insights on the human condition and to create a narrative about sexual longing, success and failure, and fear of loneliness. Moreover, my reading of the plays sheds light on how both authors deploy gossip as a tool to articulate a process of sexual and cultural ostracism, thereby fostering a dialogue with the past. This dialogue across time marks a crucial and pedagogical task in gay and queer theatre as a means to address the ongoing needs of an ever-changing community and to remind its members of previous generations’ political struggles to overcome their state of marginalization.

3 As Rosalind Kerr reminds us in the introduction to her volume on Queer Theatre in Canada (2007), the history of queer theatre in Canada, despite important pioneering efforts, is largely untold. One of the most striking gaps, I posit, is the lack of published scholarship on Gilbert and MacIvor, both of whom have established themselves as key figures in English-Canadian theatre. 4 Their plays, which frequently incorporate queer charac- ters, have received international attention and have won multiple awards. Moreover, they are a testimony to the strength and independence of gay and queer theatre in Canada, which, in the last thirty years, has clearly come into its own. At the same time, the scarcity of scholarly attention on their work is symptomatic of a need for further investigations.

4 Although the two plays discussed here are primarily concerned with the narratives of the gay male community, I suggest that My Night with Tennessee and His Greatness invite us to apply a broader queer perspective to Canadian theatre history. Following David Halperin’s evocative suggestion that we understand queer as “a horizon of possibility whose precise extent and heterogeneous scope cannot in principle be delimited in advance” and that queer “is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant” (62), I argue that the plays, as well as the gossip that inspired them, are subversively queer inasmuch as they promote an alternative understanding of theatre history by first, placing the historical marginalization of queers centre-stage and second, by keeping the respective plots outrageously sexual. While the notion of community is often contested (not least for being dominated by gay men and for its hegemonic whiteness), I agree with Tim Miller and David Román that the importance of queer theatre, which is historically rooted in the need to unite audiences and artists in their political struggle against heterosexism, should not be easily dismissed. Not only does queer theatre forge “energies to simulate and enact a sense of queer history and queer community,” but it also offers the possibility of a shared and safe social space that makes possible the staging of subcultural concerns and stories (Miller and Román 173).

5 The essay begins with a theoretical framework that outlines the intersections between gossip, theatre, and queer communities, which then informs my exegesis of, first, My Night with Tennessee and, thereafter, His Greatness. In those detailed analyses I discern similarities and differences between the two works and explain how they relate to each playwright’s respective agenda and oeuvre as well as to similar biographically inspired performances about Williams. In the last section, I discuss the broader cultural implications at stake and demonstrate how Gilbert’s and MacIvor’s plays allow for the exploration of three queer temporalities that range from the age of the closet to the HIV/AIDS epidemic to the contemporary moment characterized by queer rights on the one hand and new forms of social pressure on the other.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1Queer gossip

6 Anecdote and gossip are two phenomena that are particularly unreliable sources of evidence, yet they have become legitimate areas of interest for the humanities in general and for theatre and performance studies in particular. Scholars are increasingly directing their attention to gossip and anecdotal evidence as potential source material for theatre historiography, and as a dramaturgical device to fuel dramatic action in countless plays. In a special issue of Modern Drama on the relationship between gossip and theatre, Joseph Roach claims that gossip works in a similar way to myth in ancient tragedy, that is, as a structuring narratological facet as much as a repertoire of easily recognizable characters. Roach further notes how gossip resembles myth in its potential to create communities and draw attention to questions of normativity versus subversion: “Gossip, like myth, brings secrets into the public light, charming audiences with the socially cohesive pleasures of other people’s pain. Gossip, like myth, unites communities against deviance in the cause of normality or, with equal efficiency, against normality on behalf of popular subversion” (297). While Roach makes these observations as a starting point to explore the symbiosis between the exchange of gossip and the rise of bourgeois capitalism, my interest here lies in the potential of gossip to engender subversively gay and queer community narratives, which in turn invite us to discover and reclaim absent and neglected remnants of theatre history in Canada. Gossip as a form of unofficial and undocumented knowledge offers valuable material to approach the historical marginalization of queers, because it “serves a crucial purpose in the survival of subcultural identity within an oppressive society” (Becker et al. 31); this approach to gossip is especially useful when it concerns a canonical playwright whose entire body of work dramatizes the tension “between the need to reveal and the urge to conceal” his own homosexuality (Paller 11).

7 Well aware of their dubious status as source material, Thomas Postlewait discusses how anecdotes about famous playwrights and actors may “provide interesting, fascinating, bizarre, and sometimes definitive details about theatrical lives and events” (50) and as such have the power to invade and influence theatre historiography. Moreover, “many anecdotes not only contain a kernel of factuality but also express representative truths” (65). Similarly, Jacky Bratton notes the entertainment value of a theatre anecdote, but also asserts that “its instructive dimension is more overt. It purports to reveal the truths of the society, but not necessarily directly: its inner truth, its truth to some ineffable ‘essence’, rather than to proven facts, is what matters most—hence its mythmaking dimension” (103). Bratton further stresses that, in theatre circles, the anecdote is intimately related to “collective memory, the formation and perpetuation of group identities, and the formation of the individual within that” (104). As we will see, Gilbert first heard the anecdote about Williams in 1983, but did not produce My Night With Tennessee until 1992. After that it would be another fifteen years before MacIvor wrote His Greatness. The story about Williams’s visit to Vancouver has thus been circulating in Canadian theatre communities for decades; in some ways, it has served both as an entertaining cautionary tale and as a means to create bonds between performing artists. However, what makes this anecdote even more relevant to the formation of group identity is that its explicitly sexual content served as a source of gossip for the gay community (which in this instance overlapped with the theatre community), which used it to affirm its visibility and reassure itself of its own historical presence.

8 A number of scholars have outlined the potential connections between gossip and queerness. Chad Bennett reminds us that gossip is not always a queer phenomenon, but argues that “all gossip, by virtue of its constitutive interest in the non-normative, potentially entails queer effects” (313). This non-normativity manifests itself not least through the association of gossip with “bodies that are gendered (whether women’s talk or masculine shoptalk or scuttlebutt), classed (from servants’ tittle-tattle to society chatter), and sexualized (as in old wives’ tales, the homosexual’s camp dish, or the nosy spinster’s gab)” (314). Exploring the historical links between gossip and male homosexuality in particular, art historian Gavin Butt suggests that gossip, given its deviant and marginalized status as a reliable source in academic writing, has a “decidedly queer epistemic status” (6; original emphasis). As a result he suggests a double approach to the use of gossip as a discursive practice that produces meaning and knowledge. The first use stresses “gossip’s role in history, approaching it as an important mode of communication for disseminating queer meanings” (9). As such, it played a crucial part in an age before gay liberation; it served to disseminate unofficial knowledge and thereby make visible an historically marginalized position and identity. Indeed, gossip about Williams’s sexuality informed the reception of his plays since his heyday in the immediate post-war era, in the U.S. and beyond. 5 Of greater relevance for our context is Butt’s second use of gossip, which suggests “a consideration of how gossip’s narratives might operate as history, and how such unverified forms of knowledge might come to queer the very practice of historical accounting itself” (9).

9 My analysis is influenced by these arguments on the community-building power of gossip, its subversive potential, and the challenge it poses to normative historiography. I wish to stress that My Night with Tennessee and His Greatness are far from being the only stage works inspired by the life and work of the American Southern playwright. Williams’s life story, including his decline and fall from grace, is documented in a growing number of plays and performances, whose dialogue and plot are often assembled from various published sources such as memoirs, notebooks, letters, and interviews, and insert quotations from Williams’s dramatic characters that interested audiences can easily recognize and appreciate (LaRocque). 6 Gilbert’s and MacIvor’s plays form part of this larger phenomenon, but importantly take their inspiration from a locally specific episode and create two stage works that, despite some intertextual moments and references to Williams and his work, are independent creations that reveal important functions of queer gossip and, by extension, inseparable threads woven into the development of English-Canadian gay and queer theatre history.

My Night with Tennessee

10 As co-founder of Buddies in Bad Times Theatre in Toronto, Sky Gilbert has not only written and directed numerous plays, but also served as a mentor to countless aspiring queer performing artists. 7 In his theatre memoirs, Ejaculations from the Charm Factory (2000), he offers a detailed account of how and when he first heard about Williams’s stay in Vancouver:

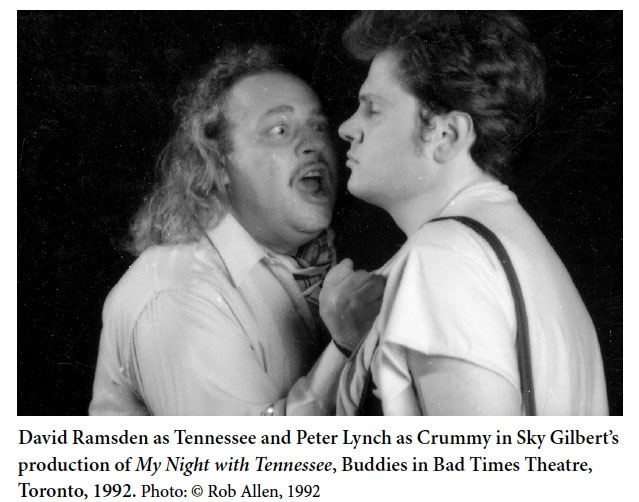

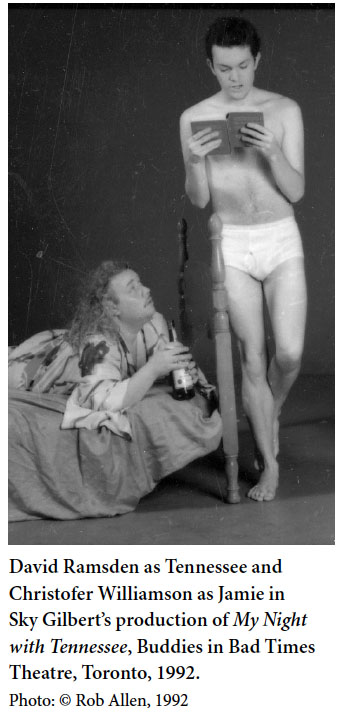

Loosely adapted from those encounters, the one-act play My Night with Tennessee depicts the triangular relationship between an elderly and once successful playwright called “Tennessee,” his assistant-cum-boyfriend Crummy whose bond to Tennessee is characterized by both love and frustration, and a teenage boy named Jamie whom the playwright first sets eyes on in a café. Fascinated by the young man’s beauty, he invites him up to his hotel room, a proposition that makes Crummy leave in a fit of jealousy. After some initial hesitation, Jamie agrees to visit, but when he knocks on the hotel door, Tennessee has passed out from a cocktail of alcohol and drugs. Once he regains consciousness, Tennessee convinces Jamie to take off all of his clothes except for his underwear and read him a poem by Rupert Brooke, whose sentimentality moves Tennessee to tears. The boy then leaves and Crummy returns to reconcile, cuddle, and spend the night with the playwright.

11 While the main source of inspiration for Gilbert is the anecdote he retells in Ejaculations, the play occasionally alludes to aspects of Williams’s works and biography. Anticipating the boy’s visit, the drunken Tennessee states that he will “await the angel… [. . .] Is it the angel that has come for me? I am ready for the angel. And when the angel comes he will not hurt me because he does not know how to hurt one as me, one as wounded as me” (161). Williams’s entire oeuvre makes frequent references to angels, and the quoted lines can be read as an allusion to the short story “The Angel in the Alcove” (1948) and the play Vieux Carré (1978), in which the main character is waiting for the angel of his dead grandmother to materialize and grant him forgiveness for his (homosexual) sins. The young man in those two works, however, is very shy and chaste, and Gilbert’s allusion seems at odds with his own unapologetic celebration of queer sexuality in all its manifestations. However, we are well served to remember that the play is not meant to be an accurate biographical study.

12 My Night with Tennessee is only one of many Gilbert plays that are based on a historical figure. Both Pasolini/Pelosi, or The God in Unknown Flesh (1983), and In Which Pier Paolo Pasolini Sees His Own Death in the Face of a Boy (1991) are dramatizations of the murder of film maker Pasolini by a teenage boy; More Divine (1994) includes a fictitious encounter between Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault; and the more recent The Situationists (2011) narrates the story of a group of intellectual and sexual revolutionaries by offering a queer take on the Situationist International. While these plays offer audiences an opportunity to rediscover and reclaim gay male history and critically review the dominant historiography that is informed by heteronormative regulations, historical accuracy and biographical correctness matter considerably less to Gilbert than dramatic conflict. Gilbert uses the historical characters as spokespersons for his own activist agenda and as channels for his own sexual politics; this usage is particularly explicit in My Night with Tennessee. For example, when Crummy has an outbreak of jealousy because of young Jamie, Tennessee justifies his actions by referring to his devotion to beauty or, more specifically, the beauty of the male body:

These lines expose more about Gilbert than they reveal about Williams, who, despite his later outspokenness on the subject of homosexuality, was never actively affiliated with lesbian and gay liberation. The character of Tennessee becomes a representative for Gilbert’s agenda to promote promiscuity as a defining feature of gay life and identity. In a provocative manner and unafraid of negative reactions, Gilbert transforms a piece of chitchat into a broader claim for and affirmative comment on gay men’s sexuality. By the time My Night with Tennessee opened, Gilbert’s outspokenness and harsh condemnation of middle-class gay men’s increasing attempts to become socially respectable by openly distancing themselves from the more sexual members of the community, including drag queens and leather men, had in fact led to outrage and severe criticism against him on several occasions. “Some fags would literally spit at me on the street,” he later remembered (Ejaculations 126).

13 In a thesis on Williams as the subject of biographical solo-performances, Jeffrey LaRocque discusses the political agenda behind My Night with Tennessee and argues that Gilbert “shifts the perception of Williams’s homosexuality from a contested space to a site of sympathy and empowerment” (40). Of relevance here is La-Rocque’s short observation on the historical moment: “Produced at [sic] Toronto in 1992, at a time when the AIDS crisis and its human devasta- tion was still in the minds of many gay men, My Night with Tennessee is a play that reconfigures Williams’s sexual behaviors as a manifestation of longing, mourning and loss” (50-51). Since the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Gilbert has been an outspoken activist against the shaming of gay men into monogamy, the risks of a renewed medicalization by the pharmaceutical industry, and the criminalization of people with HIV/AIDS (Gindt, “Your asshole”). He has regularly returned to the topic in countless debate articles, but also in several plays including Drag Queens on Trial (1985), The Bewitching of Max Gunther (2001), Rope Enough (2005), I Have AIDS! (2009), Bus Stop Hamilton (2010), in addition to the novel I am Casper Klotz (2001). Set in 1980, My Night with Tennessee never mentions HIV/AIDS, but LaRocque’s observation is nevertheless important. When the play was produced in 1992, many audience members at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre could undoubtedly relate to one of its main motifs—Tennessee’s grief over his late lover Frank, clearly identified as Williams’s long-time partner Frank Merlo who died in 1963. Tennessee’s mourning is first alluded to when Jamie knocks on the door—“I knew an angel once … but … he went away” (162)—and becomes explicit at the end of the play when Tennessee explains to Crummy how much the teenage boy reminded him of Frank. However, he also describes Frank as an inaccessible ideal:

Commenting on this paragraph, Robert Wallace argues that Tennessee “wants to relive an experience of deferral, of a desire that was only pursued, never fulfilled” (24). Frank is the one person Tennessee truly loved; yet he also admits that he never knew him, as each person forever retains a sense of mystery. Frank is sublimated into an unattainable ideal, a manifestation of beauty, artistic drive, sexual longing, and personal regret. At the same time, he also becomes a symbol of promiscuity and represents the previously mentioned “insatiable craving for beauty” as manifested by the endless chase after an always-elusive lover who “can never be gotten hold of” (24). In a 1985 paper, Gilbert identified the theme of regret and missed opportunities as distinctly related to gay men’s experiences and sensibility: “Our obsession with beauty, while at the same time the realization of the inevitability of aging, makes regret inevitable” (“A Gay Sensibility” 19). 8 Once again, the generalizing nature of the state- ment is debatable and numerous are the gay men who may disagree with it. Nevertheless, the quote is relevant in this context for enhancing our understanding of a play in which Gilbert attempts to transcend scuttlebutt about Williams’s sexual life in order to propose a larger statement about human love, sexual longing, grief over a dead lover, and regret.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2His Greatness

14 Daniel MacIvor’s play His Greatness introduces similar dramatis personae to My Night with Tennessee. Set in a Vancouver hotel room, the action spans from late afternoon just before the opening of “the Playwright’s” new stage work and a night of hedonistic partying to the brutal wake-up the following morning when the negative reviews arrive. Though the Playwright’s name is never revealed, he is easily recognizable as Williams. In honour of the occasion, the Playwright tells his “Assistant,” another unnamed character, to rent a callboy who can accompany him to the premiere. Once again, the relationship between master and servant is filled with jealousy, love, barely concealed anger, and continuous power struggles. Nevertheless, the Assistant reveals a very loving and caring side when he instructs the hustler, identified as “Young Man,” not to provide the Playwright with any drugs and only to speak highly of his plays (of which the callboy is completely ignorant).

15 Unlike Gilbert’s episodically structured play, His Greatness is divided into two acts and framed by a short prologue and epilogue. In the prologue, the Playwright addresses the audience and explains that inspiration has deserted him and that he is “in a place that must be near the end, because the river now runs dry, the voices are silent” (3). In his description of the set, MacIvor evokes vintage Williams:

The epilogue offers a coup de théâtre, as the Playwright decides to turn his infatuation with the Young Man, his complicated relationship with the Assistant, and his crushed hopes of a critical comeback into a new play. He sits down in front of his typewriter, types the lines quoted above, and reads them aloud. Theatre scholar Paul Halferty sees this framing device as a way for the otherwise realistic play—an exception in MacIvor’s dramatic output—to draw attention to its own theatricality: “In doing so, the play positions theatrical performance as a means of collective possibility through the ways it enacts dialogical communication and, hopefully, empathy” (“Defying Hope” 106). Building on this statement, I suggest that MacIvor not only uses theatrical performance, but also a piece of gossip to create a community narrative and a dialogue with the past. The play, like the anecdote, begins in a hotel room in Vancouver and the closing lines take us right back to that hotel room in 1980. MacIvor, like Gilbert, articulates the struggles and challenges of one of the community’s key figures, a significant pedagogical task of queer theatre to which I shall return in the last section. Moreover, rather than ending his play on a tragic note with the Playwright having been deserted completely, MacIvor suggests that the emotional roller- coaster of the last two days has given him a new creative burst to attempt yet another comeback in the chase of former greatness. While gossiping often serves a derogatory purpose by spreading unconfirmed speculations with the intention of defaming someone or even destroying a reputation, His Greatness proposes the opposite by showing that the Playwright’s creative spirit remains unbroken, thereby offering the audience “hope for redemption” (Halferty, “Defying Hope” 105) or, in the words of MacIvor himself, “an understanding of the transformative magic the theatre brings to our lives” (qtd. in Q&A). 9

16 Just like My Night with Tennessee, numerous parallels and allusions to Williams’s life and work permeate His Greatness, which is an exercise in playful intertextuality that never verges into superficial pastiche. 10 In the opening dialogue, the Assistant tries to wake up the hung-over Playwright with a “Rise and shine” (4), reminiscent of Amanda Wingfield’s obnoxious cheerfulness in The Glass Menagerie. Yet another intertextual reference is established when the Playwright finally wakes up and, due to a considerable hang-over, struggles to orient himself:

Assistant: Do we have to start every day like this?

Playwright: Humour me.

Assistant: A hotel suite in Vancouver.

Playwright: That’s different. And Vancouver is where?

Assistant: A city in a country north of Seattle.

Playwright: Who’s the president?

Assistant: They don’t have a president, they have a prime minister, and he’s usually somebody French. (5)

This dialogue bears some striking resemblances to the relationship between Alexandra del Lago and Chance Wayne in Sweet Bird of Youth, a play that includes some of the most famous hotel scenes in Williams’s oeuvre. Just like the fugitive actress in Sweet Bird, the Playwright does not remember where he is or who his younger companion is. This short conversation also offers an opportunity to generalize and poke fun at American citizens’ perceived ignorance of all things Canadian, including basic geographical facts. Indeed, Canadian filmmaker Harry Rasky, who produced a documentary on Williams, notes the playwright’s lack of geographical knowledge: “He always assumed, like many American southerners, that Canada was somehow all the same city. Toronto and Montreal and Vancouver must be the same place” (109). MacIvor’s witty use of this exchange in the opening scene almost certainly guarantees immediate laughter when performed north of the 49 th parallel.

17 When he finally is awake and conscious, the Playwright is interviewed on the phone about his upcoming premiere. The name of the play is never revealed, but the Young Man’s enthusiasm over “that guy’s howling” (40) alludes to Red Devil and its anarchistic ending when gang members identifying themselves as “wolves” take over the stage. The interview fails miserably, as the probing journalist upsets the Playwright who gets so agitated that he hangs up. The scene is an accurate dramatization of Williams’s complicated relationship with the press as he described it in “Too Personal,” an essay originally published in 1972 as the foreword to Small Craft Warnings. Further parallels to Williams’s life (and death) are established with the entrance of the Young Man, a street-smart prostitute and aspiring porn star who does not hesitate to manipulate people for his own benefit. In addition to working as a callboy, he also makes money as a drug dealer and provides the Playwright with cocaine and nasal spray, which the old man needs to alleviate his inflamed nostrils after sniffing the white powder. A stage direction reads: “Holding a drink in one hand the Playwright expertly opens the bottle with his teeth and snorts the spray with his free hand” (70), a foreboding allusion to the way Williams choked on a medication bottle cap and died in a New York hotel room in 1983.

18 Early on the Assistant informs the Young Man that the Playwright likes being read to, but such a scene is absent in MacIvor’s play, unlike in My Night with Tennessee where the entire plot leads up to the climactic reading. Here, however, it is merely referenced at the end of the first act, when the Young Man strips to his underwear and asks whether he should read a section from the hotel Bible. The Playwright cheekily refuses the offer, only to hand him a different book: “It’s a special night. Read one of mine” (48). Just before the Young Man starts reading and the lights fade, the Playwright exclaims: “You are beautiful. You are perfect. You are an angel” (48), another intertextual bow to Williams (and possibly to Gilbert).

19 In the foreword to the published play, MacIvor explains that he has always been drawn to the brokenness of Williams and his characters: “These plays were not slick, smooth easy rides—confi- dently built from clear thought—but rather confused and questioning and contradictory. Just like life, just like us” (ii). It was while attending the same party as Gilbert that MacIvor first heard the infamous story of Williams in Vancouver, which appealed to him as “the archetypal portrait of a broken man. [. . .] It was a story I continued to hear in different forms and from many people for years. It was the theatre practitioners’ cautionary tale. Just the way we like it, sordid and beautiful” (ii). In 2006, after dissolving da da kamera, the successful alternative theatre company that he had co-founded two decades earlier, MacIvor turned to the story as a valuable source of inspiration. At the time, MacIvor was himself “battling a few dark and poetic demons” (ii), as he mysteriously puts it, and looked critically at his previous artistic output and the perceived flaws and failures of his own stage works. While partially conceived as a tribute to Williams, His Greatness also attends to MacIvor’s own preoccupations with and doubts about success, legacy, audience expectations, exhaustion from constant touring, the euphoria of an opening night, and the brutal hangover that comes with bad reviews.

20 His Greatness illustrates the stark reality of reviews when the Playwright and his entourage come back to the hotel to celebrate after the opening night. When the papers arrive the next morning, the critics are merciless; the Playwright’s hope for a comeback is smashed once again. In this context, the idea of greatness is most explicitly debated. Whereas the Playwright once knew greatness and was celebrated as an important author, the other two characters never got and probably will never get a taste of it. The Playwright, however, also knows that “in reality greatness has no currency—it only really exists in the distance between where we think we are and what we think greatness is. It only really exists in its inaccessibility” (78). In My Night with Tennessee, Frank represents an ultimately unattainable ideal that propels the artist to love and create; for MacIvor’s Playwright, greatness constantly slips away, yet it needs to be pursued in order to give meaning to life: “Perhaps there is true greatness. In compassion, in loyalty. In love” (78). Greatness, as defined by The Playwright, is also what all of Williams’s characters long for, even though they are not always able to offer it themselves. Once again, the deployment of gossip goes beyond Williams’s escapades in Vancouver. MacIvor uses it to articulate and work through some of his own concerns at a particular time in his life. In the process he also makes an emphatic observation about the human condition, our longings and struggles, and the disappointment and disillusion when faced with failure.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 321 Both Gilbert and MacIvor dramatized the same rumour at a point in their lives when they had experienced successes and failures, on both a professional and personal level. MacIvor projected his own insecurities after abandoning da da kamera onto the character of his Southern Playwright, while Gilbert externalized his sexual politics through the character of Tennessee. My Night with Tennessee and His Greatness reveal a number of common themes, all of which we recognize from Williams’s own oeuvre: searching for beauty, being haunted by the past and the memories of broken dreams, fearing loneliness, longing for one more critical and commercial success, and deploying the combination of regret and sexual energy as a creative drive. By equating aesthetic motivation with sexual desire, the plays mirror a major characteristic of Williams’s production. According to David Savran, “one of the most persistent and compelling linkages in Williams’s work [is] the association of writing with lovemaking” (156). This relationship is best illustrated in the novel Moise and the World of Reason (1975), wherein the narrator articulates his loneliness and sexual longing by frantically writing down his thoughts and memories in his beloved notebooks, thereby illustrating “the symmetry of writing and sexuality, pencil and penis, page and anus” (Savran 156). According to Shelley Akers, for both Williams’s fictional characters and the playwright himself, acts of writing “fill an emotional void, ease physical discomfort, and satisfy sexual yearnings” (49). Writing is thus a way to give meaning to the human condition, to transcend loneliness, and to articulate desire. Most importantly, writing becomes a decisively sexual and marvellously queer activity.

Historical fragments and queer temporalities

22 Biographical information, dramatic fiction, anecdote, and gossip are conflated not only in Gilbert’s and MacIvor’s plays, but also in the general reception and perception of Williams. The two assistants and the two young men are characters that can be traced back to the omnipresent, yet interchangeable personnel that populated Williams’s life. Crummy and the Assistant are variations of the various paid “traveling companions” that Williams hired and who, according to his friend Maria St. Just, first appeared in 1962, when his relationship with Merlo started deteriorating and he needed an assistant to pack and carry the luggage (181). Rasky recalls: “There was always a Robert or Victor, some blond young man of twenty-five or so, with wide shoulders and not much to say, who was introduced more or less as Tennessee’s ‘secretary’ or ‘companion’” (13; see also Spoto 244). 11 Stories of Williams inviting young men to his hotel room or hiring male prostitutes to stay with him until he fell asleep have been repeated or alluded to in various forums. The playwright himself contributed to his reputation as an enfant terrible by openly discussing his idiosyncratic habits with journalists during his “confessional decade” (Bray 68), which stretched from Williams’s public coming out on the David Frost Show in 1970 to his death in 1983. In 1973 Williams stated in an infamous interview with Playboy:

Author and journalist Dotson Rader expresses things in a more vulgar way: “[Williams] often would call an escort service and have a male hooker sent over, not for sex but just to keep him company. He always thought he would die in his sleep, alone, so he never wanted to be alone when he took his pill and closed his eyes” (119). Truman Capote’s unfinished novel Answered Prayers includes an unflattering satire of a once successful Southern playwright who lives with his dogs in a dirty hotel room, hires callboys, and suffers from paranoia and hypochondria. In a biography that offers little insight into Williams’s work and is primarily interested in detailing his sexual escapades and growing dependency on alcohol and chemicals, Ronald Hayman insists that Truman’s caricature is an accurate portrait of the aging Williams and his “most repulsive traits” (211). All these accounts are variations of the same core theme, but their qualitative implications and vested motivations vary greatly, ranging from pure spite to a desperate attempt to sensationalize Williams. 12 Many Williams biographies are riddled with inaccuracies, factual errors or exaggerations, contaminated by (deliberate) misrepresentations and unreliable statements, and spiced with sensationalizing details about Williams’s sex life, mental health, and substance abuse to increase their commercial potential. 13

23 Though at first sight, My Night with Tennessee and His Greatness seem to follow the same pattern, they differ significantly from most of these sensation-mongering accounts. While they are undeniably informed by rumour and gossip, they do not use those accounts for self-promotion or commercial interests, but as narrative elements in a larger scheme. Here, I wish to recall the etymological origin of the word gossip, which the Oxford English Dictionary traces back to the Old English godsibb, meaning “godfather or godmother,” with whom one has a “spiritual affinity.” It is not too bold to claim that Williams ranks as one of the most influential representatives of gay and queer drama, a godfather if you will. While Gilbert and MacIvor pay homage through affinity, it is worth noting that they do not write a play about Williams at the height of his success, popularity, and artistic powers. Rather than casting him as a representation or embodiment of gay pride, they explore the downfall and decline of a once celebrated playwright who was marked and ravaged by alcohol, prolonged substance abuse, grief, loneliness, lack of success, and constant critical ridicule and homophobic attacks by the American theatre establishment. Williams’s own cultural and critical marginalization at that this point in his life offers a crucial source of identification and serves as a reminder for a community that was and, to some extent, continues to be shamed and ostracized.

24 As the late Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick cogently pointed out, every generation of gays and queers need to rediscover their own cultural history and “patch together from fragments a community, a usable heritage, a politics of survival or resistance” (81). Williams’s stay in Vancouver represents such a fragment, which is distinguished by its impressive longevity. This fragment demonstrates how gossip proves to be a useful tool in the process of rediscovering and preserving a sense of history and thereby help to foster community narrative. Moreover, it illustrates how gossip can make the move from the margins to the centre of official culture. In the words of Leigh Woods, “gossip seems oddly to appropriate a greater authority to itself once it is written down. And the more often it is written, the greater the weight of the authority it assumes” (235). Indeed, as long as the story of Williams’s stay in Vancouver was passed along from mouth-to- mouth in Canadian theatre circles, it remained in the realm of unofficial knowledge. Once written down, whether in a play or a theatre memoir, this gossip assumed a new dimension of cultural authority and was made available to people outside of the group or community of origin.

25 The various incarnations of the Vancouver story invite us to take a closer look at three layers of queer temporality. First, Williams’s visit to British Columbia in 1980 inspired the initial anecdote. In the wake of lesbian and gay liberation that was unfolding across North America, and spurred by the partial decriminalization of homosexuality in 1969, the Canadian queer community was becoming increasingly politically organized and gaining visibility, at least in urban centres such as Vancouver, Montreal, and Toronto (Kinsman 288-329). Despite these advances, the community continued to face multiple challenges and forms of discrimination, which lasted well until the 1980s, including the Cold War perception of queers as potential risks to national security (Kinsman and Gentile 221-335). Moreover, queers were subjected to organized harassment by police who regularly raided queer social spaces including bars, book stores, and, not least, bathhouses, charged people for frequenting “bawdy-houses” and placed them on trial (Kinsman 330-374; Warner, Never Going Back 99-118).

26 The idle gossip about Williams in the early 1980s was thus still very much imbricated with the realities of the proverbial closet; it served to disseminate unofficial knowledge, reaffirm a marginalized identity and presence, and strengthen the idea of community. It is also set at a liminal point, on the eve of the bathhouse riots in February 1981 in Toronto (see Hannon) and only a few months before the emergence of a mysterious and initially unidentified disease that would soon decimate the queer community (among others) and unleash a renewed wave of homophobia. When My Night with Tennessee premiered, which is the second historical moment here, the function of the gossip about Williams in Vancouver had already altered; it now offered a way to preserve a past before communal memories and recollec- tions were erased. 14 Gilbert’s play indirectly alludes to the community’s mourning at the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis. In the published version of His Greatness, MacIvor points to the significance of the time frame of his play that depicts “three gay men living fully and openly in the world of the early 80s, just before everything was about to change forever” (“Foreword” iii). This aspect is pronounced more clearly in the 2011 revival in Toronto. In the concluding monologue the Assistant now informs audiences that the Young Man will eventually get HIV, thereby offering them “a glimpse into a future—a future which from the perspective of 2011 is in fact now a ghosting past” (High et al. 72).

27 This brings us to the third moment at stake here, that is, the twenty-first century. When His Greatness opened in 2007 and again in 2011, lesbians and gay men and, to a lesser extent trans-gendered persons, had gained significant social and political rights, most notably legal recognition of same-sex marriage since 2003 (see Rayside 92-125) in addition to a larger cultural visibility. Today, queer theatre is “no longer confined to a cultural ghetto” (Miller and Román 174). 15 The queer gossip about Williams has, by now, truly come out of the closet, but this piece of chitchat originally told at a party in 1983 still proves to be of interest three decades later, even if it no longer addresses an exclusively gay or queer audience. According to Roach, “[t]he value of gossip [. . .] increases with its circulation, at least during the inflationary period before everyone who wants to hear it has heard it already” (298). Judging from the success of His Greatness, the inflation has yet to hit its peak. The next chapter is about to unfold in Montreal, where Sa Grandeur will open in the 2013/14 season at the Théâtre du Rideau Vert, in a translation by Michel Tremblay. This raises the question: why is there still a need for the dissemination of the story of Williams in Vancouver? The answer, I believe, is to be found in the articulation of cultural and sexual marginalization through theatre and idle gossip.

28 Despite undeniable political progress, we should not be blind to the multiple forms of discrimination that queers in the twenty-first century continue to experience, sometimes on a daily basis; these range from hate crimes motivated by homophobia or trans- phobia to various political and religious movements and/or parties set on implementing a neo-conservative social agenda and revoking basic human rights for both women and queers (see Warner Losing Control). While the regime of the closet has loosened over the last forty years, the main beneficiaries of these changes are largely white, middle-class, gay men, a part of the community which Gary Kinsman has identified as the “professional/managerial stratum;” these men value “an association of lesbian and gay progress with the continuation of capitalist social relations” and “want to achieve social ‘respectability’ in a social order still based on oppression and exploitation” (299). Such respectability is achieved not least through downplaying sexual outspokenness and promiscuity, but also through a disassociation with political activism and queer solidarity in order to be assimilated into neoliberal consumer culture and individualism. This process, which Lisa Duggan identifies as homonormativity leads to “a demobilized gay constituency and a privatized, depoliticized gay culture” (50). These developments make it even more urgent to write and document our own history. Even in the age of pride festivals, political rights, and greater visibility, we need reminders of our historical marginalization, of the realities of the closet, and of less media-friendly queer characters. Queer communities, just like queer theatre audiences, are not static and homogeneous entities, but diverse and dynamic, sometimes even internally conflicted groups (Miller and Román 176-77). 16 Just as the queer community continues to evolve, so too do the meanings and functions of queer gossip change over time. Queer gossip, originally and exclusively a product of the closet, fulfils different, if related needs today and helps fostering community and preserving narratives about our (theatrical) past.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the two anonymous readers and Glen Nichols for their generous feedback, John Potvin for his insightful comments on various drafts of the essay, Denys Landry for our stimulating discussions on Tennessee Williams in Canada, and Marlis Schweitzer for her careful editorial guidance.