Articles

Constellation Translation: A Canadian noh Play

Daphne Marlatt’s play, The Gull, explores the form and structure of traditional Japanese Noh theatre to expand the possibilities of translating Noh for a Canadian audience. Marlatt developed the play out of her 1974 collection of poems, Steveston, which touches on the experience of Japanese-Canadian residents of the fishing community of Steveston, BC, who were evacuated and interned during World War II. In 2006, under the direction of Heidi Specht, Pangaea Arts staged The Gull through collaboration among Japanese Noh master Akira Matsui, Noh professionals from Tokyo, and Canadian actors. This research demonstrates that the emphasis on maintaining traditional structures of Noh disrupted the potential for a well-balanced collaboration and in important ways othered the Canadian actors. At the same time, Marlatt’s script, the emotions it explored, and the aesthetic sophistication of the performance allowed for an expansive liminality of identity and location. This essay examines issues of formal and cultural translation for the stage and builds on the scholarship of Susan Bassnett and Jean-Michel Déprats. To the existing conceptions of translation as divided between acculturation and foreignization, this research proposes a constellation translation that enables the cultural locations of translator, actors, artists, and audiences to shape the production.

La pièce The Gull de Daphne Marlatt explore la forme et la structure du nô, un style traditionnel de théâtre japonais, et cherche de nouveaux moyens pour traduire le nô à l’intention d’un public canadien. Marlatt a créé la pièce à partir d’un de ses recueils de poésie, Steveston, paru en 1974, qui met en scène des Canadiens d’origine japonaise vivant à Steveston (C.-B.), un petit village de pêcheurs, et ayant connu l’évacuation et l’internement pendant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale. En 2006, la compagnie Pangaea Arts présentait The Gull dans une mise en scène de Heidi Specht ; la production reposait sur une collaboration entre Akira Matsui, spécialiste japonais du nô, des professionnels du nô de Tokyo, et des comédiens canadiens. Halebsky montre que l’importance accordée au maintien des structures traditionnelles du nô a empêché l’équipe de collaborer de façon équilibrée et, à divers égards, a placé les comédiens canadiens dans la position de l’Autre. En même temps, le texte de Marlatt, avec les émotions qui y sont explorées, et le caractère très complexe du jeu sur le plan esthétique, permettait d’étendre le seuil de perception des aspects liés à l’identité et au lieu. Halebsky s’intéresse ici à divers aspects formels et culturels de la traduction scénique et s’appuie à cette fin sur les écrits de Susan Bassnett et de Jean-Michel Déprats. Aux concepts de la traduction en tant que pratique où prime soit l’acculturation, soit l’ouverture à l’étranger, Halebsky propose d’ajouter celui de la « traduction constellaire », qui permettrait aux lieux culturels que sont le traducteur, les comédiens, les artistes et le public de donner forme à la production.

1 The Stevenson Noh Project: The Gull brought together Canadian actors and artists with Japanese Noh professionals to tell a Canadian story through the staging techniques of Japanese Noh theatre. Heidi Specht, director of Vancouver’s Pangaea Arts, spearheaded the project and invited Canadian writer Daphne Marlatt, composer and Noh teacher Richard Emmert, and Japanese Noh master Matsui Akira to join her. After a three-year development process, the production was staged in Richmond, BC in 2006 with seven Canadian actors and six Noh professionals from Japan.

2 Verbal translation was not a key focus in the production process because Marlatt wrote a script in English based on the structures of Noh. Toyoshi Yoshihara later translated the script into Japanese to allow Matsui to perform in Japanese with some English words. That Marlatt originally wrote the script in English did not diminish the many facets of cultural and formal translation that required navigation to bring the production to fruition. The struggles of employing the traditional units and structures of Noh to tell a Canadian story often fell along the familiar translation divide between what Bassnett terms acculturation and foreignization. As I discuss further below, acculturation translation strives to adjust a source text so that it fits seamlessly into the target language and culture. In contrast, foreignization translation strives to maintain as many aspects of the source text as possible, such as speech, form, and cultural references, even though these aspects may read as foreign to the target audience. A careful examination of Marlatt’s creative process reveals another potential conception of translation that accounts for the cultural locations of playwright, artists, actors, and audience. I name this method constellation translation and attribute the success of The Gull to a sensitive and fluid engagement on the part of Marlatt with both the form of Noh and how it might best be employed to illuminate the cultural history of Stevenston, BC.

3 Noh is a 650-year-old theatre art that encompasses acting, dance, music, costume, and poetry. Serious, somber, and eloquent, Noh plays often address culturally significant historical events through the experience of one character. Noh is shaped by Buddhism and plays often address the lingering attachments that trap a spirit in the world of the living. In these plays, a communication between the dead and the living offers an insight or a moment of understanding that allows the trapped spirit to find release. Noh’s reflective concentration of serious subject matter is broken by the levity of the comic kyogen interlude that often divides the two acts of a Noh play.

4 Noh dance is performed through an established set of movements called kata. These codified and stylized movements are arranged in various configurations in individual Noh plays. These movements are intricately connected with the many other performance aspects of Noh, including costumes. For example, a number of movement sequences are designed to highlight the eloquent long sleeves and silk patterns of Noh costumes. These kata are a distinguishing feature of Noh and are part of what defines a performance as within the tradition of Noh.

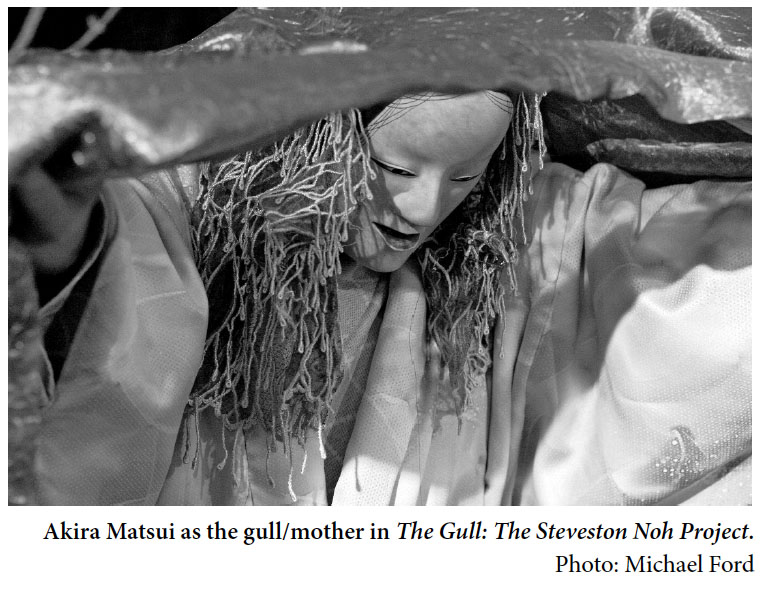

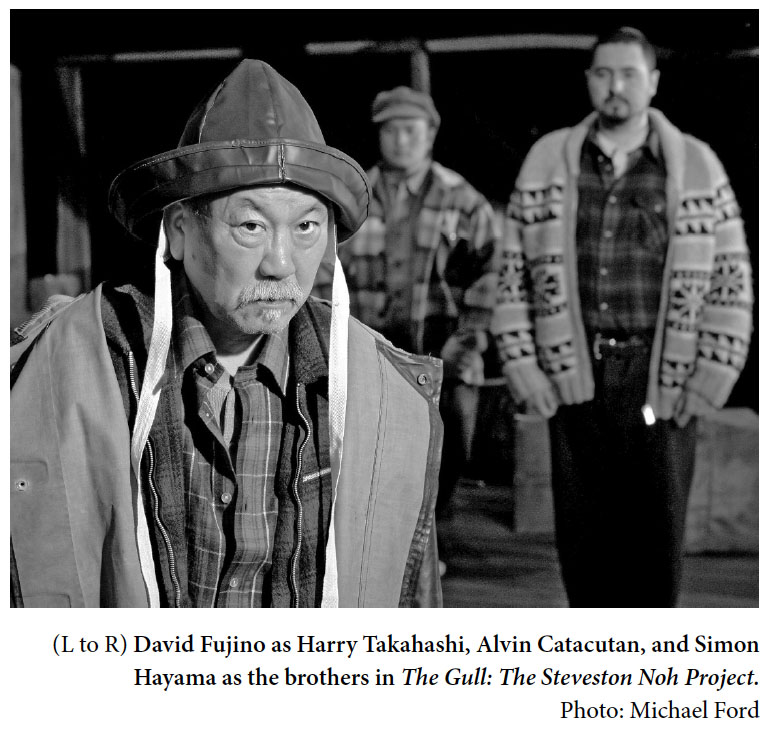

5 Marlatt’s script tells of the trauma and loss caused by the internment of Japanese-Canadians during World War II. In the play, two brothers, played by Simon Hayama and Alvin Catacutan, return to the coast of British Columbia to rebuild their lives as fishermen. The play is set in the summer of 1950: the brothers are among a number of fishermen returning to the coast one year after the federal government finally reversed its wartime prohibition against Japanese Canadians returning to the west coast (Marlatt 16). In the intervening years, the brothers have lost both of their parents. In the first act, the brothers tie up the boat in China Hat (present day Klemtu) to wait for a storm to pass. Although it is dark and rainy, they see something on the wharf. For one brother it is a seagull and for the other it is a woman. Lost and forlorn, this woman/gull, played by Akira Matsui, speaks to the brothers in Japanese with longing for her home in Mio, Japan. Toward the end of the first act, one brother realizes that the bird sounds like their mother missing her home in Mio.

6 In the middle kyogen interlude that separates the two acts of the play, a fisherman named Harry Takahashi, played by David Fujino, visits the brothers. He was a friend of their late parents and shares with them the hardships their parents endured and the hopes they held. As the brothers talk with Takahashi about their mother, waves splash the boat. The mother, in the form of a gull is trying to communicate with her sons. Her message, revealed slowly throughout the play, is for them to return home. Takahashi refuses to accept this interpretation and argues that the men are confused, saying, “Gulls sound like that. You boys have spent too long in the mountains” (59). However, he goes on to admit that other fishers have seen ghosts on their boats.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 17 In the second act, the play peaks as the brothers realize the struggles of their mother’s life and are able to apologize for not assisting with her return to Japan after the war. Within this apology, the brothers communicate that while their mother’s home was Mio, Japan, their home is the BC coast. This understanding is a moment of resolution for the mother, which allows her to let go of the lingering conflicts of her life that kept her trapped in this world. Her transformation is highlighted in an extended dance. The play reveals the brothers’ struggle to navigate identity, dislocation, and place as they attempt to rebuild their lives after the deep hostility and discrimination of the internment. Noh has a contained intensity and an immensely powerful internal concentration that made it an appropriate form to communicate a quiet simmering rage for the injustice of the internment.

8 Marlatt drew on her experiences with Steveston, her history of migration, and her ongoing study of Noh in the process of writing The Gull. Emmert, who composed the music and led Noh workshops for the Canadian actors, also served as a dramaturge and guided Marlatt on the formal structures of Noh (Marlatt, The Gull 17). The themes of the play are closely connected with Marlatt’s previous work. A ghost mother visiting living children in The Gull echoes themes of Marlatt’s volume Ghost Works (1993). Her collection of poems Steveston (1974) was about the effect of the commercial fishing industry on the quality of life of the Steveston community. Marlatt also edited the volume Mothertalk (1997) by Roy Kiyooka. Mothertalk, based on interviews with first generation Japanese immigrant Mary Kiyooka, explores issues important to The Gull, such as struggles to find and construct a concept of home and communication between immigrant parents and Canadian-born children. To write The Gull, Marlatt joined issues of displacement, identity and otherness with voices of the Japanese-Canadian experience in Steveston and Mothertalk.

9 Translation Studies scholars, such as Susan Bassnett, generally identify two main approaches to the work of translation: acculturation and foreignization. Acculturation involves the creation of a work that the audience can enter into without a conscious cultural journey. In this process, the script or source text is adjusted to the target culture in such a way that the audience can access the script without a conscious engagement with a foreign culture. In contrast, a script that retains the evidence of a different cultural location is called foreignization. In a foreignization script, translation issues of custom, culture, production language and, to varying degrees, spoken language from the source culture remain so that the audience is aware that the performance originated either in a different language or a different cultural location. Susan Bassnett describes the concerns of acculturation and foreignization:

Within these two means of translation, the eradication or recognition of otherness, issues of accessibility, aesthetic impact, and the intentions and affects of the source text are navigated.

10 The translation of works specifically intended for live performance must consider the conflicting interests of translating for the stage or translating for the page. Adaptation or translation for the stage broadly embraces change and creates a new version of a script that can succeed emotionally and aesthetically onstage, but is significantly altered from the source text. By contrast, translating for the page emphasizes fidelity to the source text. For Susan Bassnett, success in this option is found in maintaining the literary richness of the source text. For others, such as scholar Jean-Michel Déprats, this method may preserve literary features of the text but does not evoke the effect of the source text for new audiences (134- 35).

11 In discussing the verbal translation of Shakespeare, Déprats notes a third possibility for translation and suggests that a sourceorientated translation created by “major poets or well-known playwrights,” even with limited knowledge of the source language, can create a stunningly rich translation (134). In this third way, Déprats argues that these “famous writers” can understand how the words of the script are performed through the actor’s body and thus create a target language script that can work well onstage. Through Marlatt’s creative process, I explore why a famous writer would be more adept than a skilled translator in making a successful translation. I make a significant departure from work in theatre translation studies by positioning formal production values and areas of creative mastery such as creative writing, Noh kata, and Western acting technique as languages in and of themselves. Within these production languages artists have varying degrees of fluency. Marlatt’s success in writing The Gull did not reflect a particularly intricate knowledge of Noh, but rather, was brought to fruition through her richly cultivated creative practice.

12 To Déprats’s third way, I add constellation translation, which is the ability of these writers to bring voice, and thus a synergy and resonance, to a translation. In constellation translation, a work is shaped by how the concepts and aesthetics of the source text are interpreted and revisioned by the translators. The translators include not only the writer but also the various artists involved in the production, such as actors, musicians, set designers, and costume designers. Rather than being a transparent medium with no influence on the artwork, the translators are aware of and embrace how they shape and integrate their own experiences and points of view into the work through the translation process. Attempts to hide the process of change in a translation can create internal conflicts within a work that weigh down the aesthetic energy of a production. Constellation translation seeks to diminish the romantic possibility of a work that can be both translated and unchanged.

13 Constellation is a series of independent points that connect to and shift proximities with other points. This constellation image reflects the creative process of finding points of connection among lived experience, cultural knowledge, and the source text. This process rests on the artists drawing from their embodied experiences and the cultural knowledge held physically in the body. A creative writer, such as Marlatt, has cultivated her ability to draw from her own embodied experiences and articulate those experiences in words. Constellation translation offers a means of translation that can reveal the fissures, folds, and struggles of the translation process. In these works, the evidence of the translation process and the transformations involved are not only made visible to the audience, but are also embraced as part of the cultural journey of translation.

14 Specht saw The Gull production as a way that formal theatre techniques of performance in Vancouver might reflect the area’s cultural history and diversity (Specht).1 Specht is a talented director with training in many different theatrical traditions and a particularly keen aesthetic sense. Her work is influenced by earlier multicultural initiatives that promote theatre and the arts as a point of connection among ethnic and social groups. Other Pangaea Arts productions, Butterfly Dream (2004) and Jade in the Coal (2010), brought together spoken drama and Chinese Opera theatre artists. This facilitated connections among groups in Vancouver and gave broader community access to an active theatre form within Canada. One significant difference between Chinese opera and Noh is that Noh is not currently practiced in Vancouver. In this way, Noh was not an immediate point of connection between Pangaea Arts and the Japanese-Canadian community. Nonetheless, Specht sought to cast JapaneseCanadian actors and to hold community feedback sessions as modes of community involvement in the production. The Gull was produced during the lead up to the 2010 Vancouver Olympics, which generated interest and funding for positive representations of Vancouver to Canadians and the international community.2

15 The Gull’s production team with Specht as director and Emmert as Noh teacher encountered difficulties in using Noh to showcase Canadian diversity for a number of reasons. Traditional theatre forms, such as Noh, might seem like a way to perform diversity because they can function as a representation of cultural otherness onstage; however, multiculturalism requires the performance of otherness as part of a Canadian identity. To support diversity, otherness needs to be presented as simultaneously other and Canadian (See Kamboureli 92; Shimakawa 150). Employing a foreignization translation of Noh, which heightened Noh as distinctly Japanese, further diminished the possibility of presenting Noh as part of a Canadian identity.

16 Noh is a marker of otherness onstage due in part to the way it is promoted both within and outside Japan as a uniquely and distinctly Japanese form. As Eric Rath outlines, Noh’s role in society shifted with the many changes brought by the Meiji Restoration of 1868. As Japan opened its doors to the West, the Meiji government sought to build diplomatic relations with America and Europe. They positioned Noh as a traditional Japanese art on par with Western opera and suitable to share with foreign dignitaries. With Noh the Meiji government could present Japan as refined and sophisticated to the rest of the world. Into the Meiji era, with the growing Western influence in many facets of Japanese cultural production, the government sought to promote Noh within Japan as a means to resist Westernization. Rath explains that at the time Japanese historian Kume Kunitake, “advocated that Japan needed pure traditions such as noh [. . .] to preserve and strengthen its native spirit” (224). In this context, Noh became a symbol of an art form untouched by Western influences and celebrated as purely Japanese. Noh has since come to symbolize Japan, marking Japanese-ness within Japan and as presented to the rest of the world through the vehicles of tourism and arts culture initiatives (See Brazell 20-22; Gordon 108-109; Rath 220-24).

17 Multicultural productions are often criticized for presenting an idealistic view of social harmony within a diverse community that masks the inequalities and ethnic hostilities endured by marginalized groups. The Gull, however, gave voice to the struggles of identity and belonging faced by Japanese-Canadians in the aftermath of the internment. In the 1970s and 1980s, the National Association of Japanese Canadians led the Redress movement that called on the government to acknowledge and address the human rights violations of the internment. One of the hard fought gains of this movement was an endowed fund to support activities related to Japanese-Canadian identity. The Gull drew attention to injustice in a historical context, which allowed for an implied critique of current inequalities. The importance of The Gull’s message is reflected by the groups who chose to support the project, including The National Association of Japanese Canadians, the National Nikkei Heritage Center, and the Japanese Canadian National Museum.

18 In The Gull, Japanese nationals performed an art form that marks Japanese-ness. While the production demanded that Canadian actors perform traditional Noh in a foreignization translation, Canadians of Asian descent performed in a production language that marked Japanese-ness. At the same time, the verbal script articulated their identity as Canadian and othered within Canada. Hence, the characters in the script had an agency and a complexity of identity that the Canadian actors did not have within the production. The performance skills of Noh require years of training. Without an active Noh practice in Canada, it was difficult to find actors who had sustained training in Noh. Actor Simon Hiyama has Japanese heritage and grew up in Steveston. Actor David Fujino was brought in from Toronto for the production. Fujino is Japanese-Canadian and has a close personal connection with the subject matter of the play as he was born in an internment camp mentioned in the play. The employment of the physical structures of Noh in movement and acting technique that strived to adhere solely to traditional Noh caused alienation and diminished voice and agency for the Canadian actors.

19 The Gull was portrayed as “[a] collaboration between Canadian theatre artists and Japanese Noh artists.”3 Marlatt developed the content and structure of the script in a responsive dialogue with Emmert and Specht. As mentioned earlier, Marlatt drew from her personal location, her experiences with Steveston, and her study of Noh in the creative writing process. In contrast, many facets related to the production language of traditional Noh had finite value structures that did not allow for individual interpretations of Noh. The emphasis on a foreignization translation of Noh limited the agency of participants to structure and define individual cultural locations. By emphasizing a foreignization translation, the structure of the production positioned the traditional form of Noh and its established kata as correct performance technique. In correlation, this positioned the acculturation of Noh and a Canadian influence on the physical structures of Noh not as new versions of the form but as failed translations of traditional Noh.4 This value structure diminished the possible degree of collaboration because participants were not able to contribute their points of view and prior knowledge to the process.

20 The collaboration in The Gull was not equally weighted among Japanese and Canadians in a shared learning process. The imbalance was apparent to this observer in the rehearsals leading up to the production and confirmed later in actor Fujino’s reflections on his experience published in the Japanese-Canadian newspaper, Nikkei Voice. The Canadian actors were paid not only for the rehearsal of the production but also for the Noh training workshops. They were to learn from their Japanese counterparts, but this did not go both ways. The Japanese Noh artists were to perform in a manner that was traditional and correct to the form of Noh rather than learning from the skills of the Canadian actors. Because the production aimed specifically to be as close to the traditional form of Noh as possible, it did not require the Japanese Noh professionals to learn new performance techniques. This structured the production process so that the professional Noh artists were positioned as authorities and the professional Canadian artists were positioned as students.

21 Canadian cast member Fujino, while very much supporting the project, took issue with the power dynamics between the Canadian actors and the Japanese Noh professionals. In an article in Nikkei Voice, Fujino writes:

Fujino’s comments reflect his dissatisfaction at being part of a collaboration with a definite power structure that situated Noh professionals as authorities and Canadian actors as students and novices. While the Canadians, with the exception of the second supporting actor, were new to Noh, their training as actors and professional experience was not considered a point of contribution to developing the physical structures of the play. They were expected to use their Western spoken drama skills to help them perform traditional Noh well rather than to re-vision Noh for a new cultural location. The result was that the actors performed with their limited skills in Noh rather than integrating their formidable performance skills with the skills of their Japanese counterparts. Ultimately, the acting was a muted version of Noh movement. Their postures, stances, and gestures were within Noh form, but they did not attempt the flourishes of Noh in its complex movement patterns. This muted version of Noh was a failure in the translation process; in effect, the request that the actors only perform Japanese Noh meant that they had to hide their cultural location, particularly in the physicality of their acting.

22 Because of issues that included a limited training time, the comic interlude kyogen scene was adjusted to allow for a less than strict adherence to kyogen movement and speech. The departure of the kyogen scene in The Gull from strict kyogen technique was of great assistance to the overall reception of the play. In the scene, Harry Takahashi comes to visit the brothers on the boat and realizes that he knew their parents. He tells the brothers tender, sad, and humorous stories about their parents. This includes how their father sent a much younger picture of himself to Japan when searching for a bride. The picture leads to their mother coming to Canada much younger than her soon-to-be husband. Harry Takahashi explains, “Aaah! (smacking his lips) Your mother now, she was quite a woman. She had that old Wakayama spirit. What a catch! I used to kid your dad about being a highliner in more ways than one” (Marlatt 58).

23 In keeping with tradition, the kyogen scene in The Gull was a drinking scene. The brothers poured whiskey for the kyogen actor and he drank it in the formal way of angular, sequential movement in the action of drinking from a cup and then indicating swallowing with pursed lips and a satisfied breath out. Fujino gave an energetic performance with humorous dialogue, animated drinking actions, and surprise movements of the waves hitting the side of the boat. Fujino, however, did not escape criticism for differing from traditional form. At the cast party he received feedback from one of the Japanese musicians on the show. In complimenting Fujino’s work, the musician also pointed out that his performance differed from the traditional kyogen and insinuated that this difference was not desirable. Fujino writes:

24 This discussion reflects a structure where traditional Noh and foreignization translation is correct and a Canadian acculturation of that form is not a new translation but an imperfect version of the original. Fujino’s sidebar, “Welcome to Canada,” may read like a sarcastic comment about drinking within Canadian culture, but it points to a broader issue. He is marking The Gull as a Canadian production imbued with the mannerisms and attitudes of the Canadian participants; his comments suggest that the production should not be seen as incorrect Noh but as a Canadian version of Noh, which will be different from Noh in Japan. This, too, can function as a metaphor for the Japanese-Canadian community, no longer exclusively culturally Japanese but informed and shaped by cultural ties to Japan and lived experience in Canada. The actors were not asked to interpret their exposure to Noh or to draw from their cultural location in their performance. Within this structure, it was possible for the Noh artists to view the acculturation of Noh as imperfections in the form rather than as a means of creating a new perspective.

25 Pangaea Arts sought community participation and a broader impact for The Gull through staged readings, Noh workshops, and a Noh mask exhibit. One of the important aspects of involving the Japanese-Canadian community in The Gull was the staged reading held in May 2005. At this event some of the performers wore Noh clothing of dark kimono and wide split-leg pants. Feedback from the audience, which included a significant turnout of first and second generation Japanese-Canadians, requested that the brothers wear costumes that reflect the clothing of fisherman in the 1950s rather than Japanese Noh costumes. This feedback was acted upon and in the final production the actors wore clothing typical of coastal fishing the in 1950s such as a cable knit wool sweater and a plaid work jacket.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 226 Specht’s willingness to respond to feedback from the staged reading demonstrated her commitment to involve the local community. However, it also created a conflict in the acculturation/ foreignization translation of Noh. Noh kata, which include set units of movement, are arranged, sequenced, and patterned into different dances. Part of the structure of these movements is to show the audience the beautiful, highly detailed Noh costumes. The sleeves of Noh kimono are an especially dazzling part of the costume. Master artists make highly ornate and detailed silk kimono with patterns that display aspects of a particular character. For example, a character who will turn into a snake wears a diamond patterned kimono. The colors and designs of the kimono are part of what communicates a character’s age, gender, and disposition. Noh movements aim to show off the pattern and long flowing sleeves of the kimono. In these movements, the visual effect is created not through movement alone, but by how the movement displays the costume. When the costume is changed, particularly to a sweater that does not have flowing sleeves, the Noh movement is taken out of context and loses its significance. This was a major roadblock in acculturating some aspects of Noh’s production language into The Gull. Changing the costume to a localized, Canadian style lost the significance of the movements of Noh dance. If the dance is then maintained in Noh kata with a localized costume, it is for the sole purpose of being “like Noh,” rather than creating the artistic effect of traditional Noh. The production team ultimately resisted a better integration of costume and choreography values in favour of a foreignization translation that sought to maintain Noh kata.

27 Overall, the foreignization in The Gull’s casting and acting technique ran up against problems that Marlatt’s writing process navigated successfully. The collaboration structure that valued traditional Noh over Canadian contributions displaced the Canadian actors. The actors were denied the opportunity to perform from a point of fluency in spoken drama, which hampered their ability to bring an energy or excitement into their performance of Noh. They did not have agency in discussions about how their roles should be performed. Their point of view was diminished within the acting technique of the performance, which caused their performance to be subdued. Marlatt’s script, on the other hand, is an example of how work that reveals translation as a process of change can succeed, and allow the actor other ways of embodying the aesthetics of Noh.

28 Central to Marlatt’s translation process is the concept of change. Change is a key tenant in the Buddhist philosophy that informs the aesthetics of Noh and is also a strong theme in The Gull. Marlatt’s script aligns acculturation translation and foreignization translation as unfixed and shifting points in a constellation of fluencies. In this translation, values that attempt to define traditional Noh and Canadian culture are sets of symbols that shift and move in relationship to each other. Ongoing change is made explicit at points in the script. As the mother asks her sons to return home, the chorus chants, “home, it changes like the sea’s/rough waves we ride/its changes constant, changing/our quick lives—” (72). The word/symbol for home is revealed to have different meanings depending on the context and the speaker. This meaning can also be understood as created through its location within a constellation and reveals the mother’s location as different from each of her sons. Here the process of change in translation brings together shifting cultural locations between generations within this family. Other lines from this section point more directly to how the meanings of words shift with location and point of view. The supporting actor speaks to the bird/ his mother: “what was home to you/Mother, is not home to us” (71). This line unswervingly shows that the meaning of words can change because the values of points within the constellation are in constant flux. The change manifest in our brief lives is evident in the change of point of view among generations, individuals, and also in the meaning of distinct words.

29 Marlatt’s background and history of confronting difference, in addition to her cultivated writing practice, contributed to the success of The Gull. Marlatt’s constellation translation reveals different points of view in the play through the brothers’ challenge to find and access their mother’s position. When the mother/bird first comes to the boat, one brother sees a woman and the other sees a bird. Two people look at the same image and see it in stark contrast. This is a metaphor for how words work in translation. They do not hold fixed meanings because their meaning is created through the standpoint of the reader and the work of reading.

30 Lingering attachments that the dead have with the world of the living are a central theme in Noh. A Noh play often presents a moment when these attachments can be resolved. The most important journey in The Gull occurs when the mother communicates her feelings and the sons come to understand that their point of view and interests are different from their mother’s point of view. After the war, the mother had wanted to repatriate and leave Canada. However, her Canadian-born sons, despite the hostilities of the war, wanted to stay in Canada. Resolution for the ghost of the mother is accomplished when the son gains insight into his mother’s outlook as different from his own. He says, “Mother, we failed to understand/how deeply you felt/abandoned there—” (71). Through this insight, the brother shifts his location in the constellation. For this moment, the proximity among the sons and the mother is diminished. It shows that we can create and change our locations within the constellation. It is also the communication the mother needs to resolve her attachments with the living world.

31 The shift in proximity among the points of view of the sons and their mother reflects the core interests of Marlatt’s writing. She writes from the edges, from places of otherness and marginalization. As seen in The Gull, Marlatt strives to find points of connection and means for people to come together in ways that maintain a respect for difference. In Readings from the Labyrinth, she articulates the challenge of creating difference at the same time as creating shared ground:

Here Marlatt describes othered groups as the many fringes, opening the concept of multiple identities and multiple ways of being outside of dominant society. She uses the word delicate to stress the difficulty of making relationships among othered groups in a way that supports difference while at the same time finds points of connection. The brief quotation above is an example of the issues that guide much of Marlatt’s writing and inform the themes of The Gull. She draws on the ways in which she is othered as woman and immigrant in order to explore shifting personal locations and identities.

32 In her work, Readings, Marlatt positions her writing process as a body-based practice in which she makes an intentional physical journey. Déprats attributes a successful translation to the ability of the translator to create a text that actors can physically perform well (136). However, the success of Marlatt’s writing is found in her embodiment of the translation process. To write The Gull, Marlatt pulled from the corners of experience stored in the body, and connected memories from her earlier works, Steveston and Mothertalk, with the compositional structure of Noh. The Gull reveals issues central to Marlatt’s journey that recur in many of her writings. She explains:

Through the concept of “drift,” Marlatt explains a process of finding meaning through writing rather than attempting to explain predetermined ideas. This responsiveness reflects Marlatt’s process as based in learning and exploring shifting complexities in creating a text. Her ability to link into a body practice that can navigate multiple stories, histories, and situations comes from a fluency in a highly attuned writing practice. This synergy of multiple influences with a creative writing practice is what differentiates an accomplished creative writer’s translation from a skilled linguist’s translation. The “drift” that Marlatt describes allowed for the changes in point of view and Noh form that are key to the responsiveness of her script.

33 Marlatt offers a third way of translation that, because it has no fixed points, requires an attention to the present moment and a sensitivity to shifting values. This constellation translation exists through spectators actively creating their own points of engagement within the play. While Marlatt’s verbal script gives voice to constant change, this change is also present within the structures of the script. Both assist the audience in making significance. This active engagement on the part of the audience involves the audience in finding their own connection to the script and navigating their own shifting locations within the constellation.

34 As a performance, The Gull adhered to many of the structures of traditional Noh and, at the same time, resonated with historical and emotional sentiments within Canada. Adhering the physical performance of the play to the structures of traditional Noh disrupted the possibilities of constellation translation on the part of the Canadian actors. All artists need to find their own relationship with the form and subject matter of a production. Strict adherence to Noh kata was problematic because it displaced what should have been the Canadian actors’ task of finding their own meanings in the Noh form and The Gull script. While Marlatt’s text openly demonstrates the translation process, the actors were asked to conceal their processes of interpreting Noh. Ideally, a constellation translation supports all artists in making their own connections within the translation. With each connection, little points in a constellation, locations shift. This continual shifting is part of the energy and vibrancy of a translation that make it alive, urgent and responsive to contemporary experience.

35 Conflicts around issues of acculturation and foreignization brought up many difficulties in employing Noh in The Gull. These difficulties are present in the undercurrents of daily life in Vancouver and reflect the struggles of migration: how to become Canadian, how to maintain distinct identities, and how to confront historic and continued hostilities. Noh in The Gull did not cause these difficulties nor were these difficulties failures of the production. The Gull created an opportunity to explore the problems constructively within the context of the production, which are also present in contemporary society. The Gull allowed for a reflective and emotive engagement with issues of diaspora and dislocation. It asked the audience to address the legacy of the internment. It also drew attention to the permitted social locations of othered groups through the example of Japanese-Canadians and showed shifting constellations of identity. These issues were not resolved in The Gull, but their articulation presented an occasion to begin to address them. Marlatt created a nuanced script that had space within it for the diverse audience to connect with the production and find voice within the performance.