Article

Interculturalism and Theatrefront:

Shifting Meanings in Canadian Collective Creation

This essay examines the process and product of a collaboration between Toronto’s Theatrefront and Cape Town’s Baxter Theatre. The intercultural work Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) expressionistically performs the stories of two generations of a South African family and a Canadian family as their complex associations are revealed against the backdrop of a Toronto university. Ubuntu, a Xhosan word, means, loosely, “a person is a person through other persons”—both community and ancestry—a philosophy that informed both process and production. Through an examination of the histories and mandates of both companies, read through Christopher Balme’s concept of theatrical syncretism, this essay argues that Theatrefront both borrows from and expands the parameters of the tradition of collective creation in Canadian theatre in this collaboration. As it explores perennial questions of self, national, and theatrical identity, Theatrefront employs indirect, globally-minded approaches to collective creation.

Dans cet article, Ratsoy examine le processus et le produit d’une collaboration entre deux compagnies, Theatrefront de Toronto et Baxter Theatre du Cap. Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project), une œuvre interculturelle, met en scène le récit expressionniste de deux générations d'une famille sud-africaine et d'une famille canadienne et leurs associations complexes, avec une université torontoise comme toile de fond. Ubuntu, un mot de la langue xhosa qui signifie grosso modo « une personne est une personne à travers d’autres personnes » —à la fois au sein de sa communauté et parmi ses ancêtres—a informé à la fois le processus de création et le produit qui en a découlé. Ratsoy examine l’histoire et le mandat des deux compagnies à l’aide du concept de syncrétisme théâtral de Christopher Balme, et fait valoir que la démarche de Theatrefront emprunte des éléments à la tradition canadienne de création collective théâtrale tout en élargissant les paramètres de celle-ci. Dans son exploration de question récurrentes liées à l’actualisation de soi, à l’identité nationale et à l’identité théâtrale, Theatrefront emploie des approches à la création collective à la fois indirectes et ouvertes sur le monde.

1 Atestament to the spirit of community and the interconnectedness of all humans from its title onward, Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) expressionistically performs the story of two generations of a South African and a Canadian family as their complex associations are revealed against the backdrop of a Toronto university. Ubuntu, a Xhosan word, means, loosely, “a person is a person through other persons”—both community and ancestry; as Daryl Cloran writes, “This one word [Ubuntu] illuminates both the content of the play and the creative process itself” (i). This Theatrefront collective creation, directed by Cloran, transcends naturalistic temporal and spatial conventions.

2 Jabba, a young South African haunted by a desire to find his missing father, Philani, who left to study in Toronto two decades earlier, retraces Philani’s steps to a microbiology professor, Michael, who denies any knowledge of Philani, despite the fact that Jabba possesses a photograph of the two men together. As the time shifts to Philani’s student days in Toronto, we learn that Michael was, in fact, Philani’s advisor. The lives of the two men are more complexly connected through the character of Sarah, Philani’s lover. In the present time, Sarah’s death has taken a toll on her daughter, Libby, and Michael, Sarah’s husband. Persistent, Jabba capitalizes on a chance meeting with Libby, and the two, eventually aided by Michael’s confession, untangle the complex mystery of the intertwining of the two families. The Sangoma, a Xhosa healer, provides an expressionistic, spiritual, atemporal dimension to the play, an atmosphere augmented by the imposing walls of suitcases that dominate the stage. Metaphors for mobility, transience, and displacement, the suitcases also serve myriad functional purposes as the plot unfolds—hiding a revolving door and transforming into other props, for example. A caretaker at the mausoleum where some of the mystery unravels, played by the same actor who plays Michael, is the sixth character. The play ends with Jabba’s return to South Africa and his eventual acceptance of the cultural differences with which his father could not cope. Dance, mime, and other physical elements add texture to this mystery/love story.

3 The spirit of Canadian collective creation is evident in Theatrefront’s work, with its rejection of hierarchy, reflection on process, and emphasis on inclusion. Scholars credit Theatre Passe Muraille with originating and popularizing collective creations in Canada. Alan Filewod’s description of The Farm Show (1972) perhaps best defines the early stages of the movement as “community documentary theatre based on the actors’ personal responses to the source material” (Collective 24). Other early work of Theatre Passe Muraille, such as 1837: The Farmers’ Revolt, employed the local and the historical to reflect contemporary national, social, and political concepts, often concerning itself with exploring national identity to construct national myths.

4 A subsequent generation of collective creators, while respecting the elements of process popularized by Theatre Passe Muraille, was less occupied with using history to construct national myths of identity than it was to broaden the concept of Canada and interrogate and undermine monolithic constructions of nationhood. Illustrative of this stage is NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints), a group initiative spearheaded by David Diamond, founder and long-time director of Vancouver’s Headlines Theatre, which saw the company and locals in Kispiox, BC, working (over a four-year period from 1987-1990) from conception through several production rewrites with the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs; the published script is coauthored by Diamond, Hal B. Blackwater, Lois Shannon, and Marie Wilson.1NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) was performed by Indigenous and non-Indigenous actors and incorporates both Aboriginal oral history and written documentation. The play, which encompasses several time periods and centres on Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en history and traditions in both its plot and staging, focuses on the perspectives of two couples, one indigenous to the area, the other Scottish immigrants, on the land claims of the Northwestern British Columbia First Nation.

5 Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) has much in common with NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints). Although it does not rely on historical documents, it eschews the overtly political, and, most saliently, conjoins Canadian and South African theatre in a single work, and thus extends the boundaries of the collective creation form in innovative ways. Superficially, perhaps, the structure of the titles of the two works—incorporating two languages and privileging the non-English words—is similar. More deeply, both plays are as much about process as product—“collective,” “collaborative,” or “devised” creations; both also performatively foreground the communal over the individual and both reject simple binaries. Although NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) is a resolute statement on the ongoing injustices of the project of colonization, the play, through the individual and collective actions of the two couples, places blame not on individuals, but on systems and bureaucracies, and is as concerned with illuminating possible solutions as it is with decrying problems. It also, as significantly, makes a performative statement through the incorporation of Western and Indigenous performance traditions. As the introduction to the work in Playing the Pacific Province states, “Fittingly, given its explicit message about the importance of all peoples acting in harmony with each other and the earth, the play [. . .] is a harmonious fusion of elements of aboriginal and western cultures [. . .]. NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) also incorporates Native spiritual beliefs in transformation [. . .] as it elides conventional time barriers” (396). Likewise, Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) incorporates South African and Western performance traditions, de-privileges Western concepts of time, and highlights nonWestern spiritual beliefs. In terms of binaries, the Western rationalist thinking and apparent emotional detachment of Michael at first seems purely oppositional to the spirituality of Philani and the Sangoma, and the conflict between the two cultures in which Philani participates is clearly problematic for him. However, as the play progresses, while some of Michael’s motivations remain open to conjecture, the scientist reveals inner emotional and intellectual realms that efface the simplicity of pure oppositions, and Jabba’s ultimate responses to Canadian culture indicate his acceptance of differences. In short, both plays address and deconstruct notions of alterity, mirroring in content and style their collective processes.

6 Both plays belong to the intriguing, complex world of crosscultural theatre, defined by Jacqueline Lo and Helen Gilbert as “performance practices characterized by the conjunction of specific cultural resources at the level of narrative content, performance aesthetics, production processes, and/or reception by an interpretive community” (31). Using Lo and Gilbert’s framework, I categorize NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) as intracultural, a production built on “cultural encounters between and across specific communities and regions within the nation-state,” a concept they distinguish from multicultural in that it highlights diversity and interactivity, rather than assuming cohesion (38). Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) is, in their topology, extracultural: a production conducted along a North-South axis, encompassing intercultural experiments, and celebrating and scrutinizing cultural differences “as a source of cultural empowerment and aesthetic richness” (38). They distinguish it from transcultural, which they perceive as cross-cultural theatrical endeavours “to transcend culture-specific codification in order to reach a more universal human condition” (37), although extracultural theatre may incorporate some aspects of the transcultural, as Ubuntu does. Perhaps Mayte Gōmez, in the context of Toronto’s intercultural theatre scene, makes the latter distinction patent: “To search for the universal takes us to the normative, to the static and unchangeable. To search for difference creates movement, interaction” (41).

7 The work of Theatrefront, officially incorporated as a notfor-profit company in 2001, can be viewed as extending beyond geopolitical borders the work of Vancouver’s Headlines Theatre, which Diamond founded in 1981. In the intervening two decades between the founding of the companies and in the subsequent decade since Theatrefront’s incorporation, technological change has precipitated previously unfathomable virtual and actual exchanges. Headlines itself has extended its reach to work with different cultural groups in communities throughout the world and takes pride in its role “as a political theatre company [. . .] to lead in the popular use of new technologies” (Diamond, Moment 12). However, additional factors point to Theatrefront as both an heir to the work of such collectives as Headlines Theatre and a distinct young company that reflects additional layers of complexity that have been woven into the Canadian fabric over those decades.

8 NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) can be seen as a second step on a Canadian collective creation continuum. Filewod notes that the 1980s saw a shift in thinking in Canada: “Now the terms of colonization had more to do with gender and ethnicity than with imperial affinities” (“Imperialism” 66). The rise of Quebec nationalism and the country’s changing demographics “showed the nationalism of the 1970s to have been the artefact of a particular segment of Canadian society,” rather than being reflective of the nation as a whole (Filewod, “Erect” 67). Although Filewod suggests that the institution of Canadian theatre was not substantially affected by such government policies as official multiculturalism, I argue that there were some notable “alternative theatre” exceptions. Headlines Theatre came into existence when a group of Vancouver theatre artists “hungry for creative experiences that were connected to reality” found a “real life” social purpose—to draw public attention to a housing crisis in Vancouver (Ratsoy 393). By 1987, when work on NO‘XYA’ (Our Footprints) began, the company had undergone significant artistic and philosophic changes, but that social purpose was, if anything, more deeply felt and thoroughly entrenched. Filewod observes elsewhere that the play “rests on the premise that the white colonizer can participate in and learn from Native traditional culture” (Filewod, Political xi). As I will make clear later in this essay, a similar premise led Theatrefront to approach South African artists.

9 Filewod’s point is significant for at least two reasons: first, it indicates an openness on the part of the Aboriginal partners to having their culture “participated in,” and second, it suggests that the non-Aboriginal partners are in some senses audience to the process and production: students and participants; producers and audience. Furthermore, Diamond reports that when the play was performed in Rotorua, New Zealand, the representative of the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en chiefs, Ardythe Wilson (Skanu’u) organized post-performance ambassadorial sessions with the Maori, who repeatedly saw NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) as “[coming] from another part of the world but [telling] their story” (qtd. in Ratsoy 395). It is also noteworthy that the company’s current website archives credit the play, which was first produced in Kispiox and subsequently toured Canada as well as Maori communities, with “In its small way, [. . .] help[ing] pave the way for the now famous Delgamuxw Court Case that has redefined Native Rights in Canada” (headlinestheatre.com). In retrospect, then, the play’s cultural efficacy is depicted as starting with the non-Aboriginal co-creators, moving to its broad (geographically and culturally) audience, and transcending both to have a very “real world” impact—as contributing to measurable political change within a nation state. This claim, while difficult, if not impossible, to prove, reveals much about the company’s intentions and self-image.

10 NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) seeks to create identity by revisioning historical events, representing the past as a kind of mobile backdrop acting on the present, and foregrounding group creation. The play also extends the processes of earlier collective creations by both critiquing the (historical and contemporary) nation state and fostering intra- and intercultural dialogue with its overt agenda of “social change.” Headlines Theatre, as its website proclaims, utilizes theatre for the ends of “conflict resolution [. . .] community healing and empowerment” (headlinestheatre.com). Earlier collective creations construed their audiences as rather narrowly defined Canadian ones; although NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) exemplifies intracultural theatre, the audience reaches across the world, the commonality being not the nationstate (or a province therein) but a similar history of colonization. In less than two decades, concepts such as “community,” “nationalism,” and “imperialism” assumed new and diverse connotations.

11 If vast and complex change informed the political and social landscape in Canada between the early 1970s and late 1980s, the next fifteen years saw transformation that could best be described as monumental. Federal politics would move in directions highly unpredictable in the late 1980s. Economically, the Free Trade Agreement with the United States in 1987 and the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994, which created the world’s largest free trade area, were part of a proliferation of “globalization” movements. Immigration was also changing the face of Canada: by 2006, Statistics Canada reports, 42% of Vancouverites and 43% of Torontonians were “visible minorities” (Study). In short, both internal and external forces re-created an ever more complex Canada.

12 That changes in a globalized, technologically mediated, and highly intercultural Canada have left an indelible mark on Canadian theatre has been widely acknowledged within the discipline. In 2002, Jerry Wasserman wrote, “Today, Canadian plays peopled by African-, Latino-, Native- and Indo-Canadian characters, among many hyphenated others, examine personal and cultural boundaries complicated by postcolonial hybridization, media manipulation, and fractious diasporic politics” (82-3). Seven years later, Ric Knowles indicated the increasing importance of intercultural theatre in Toronto, specifically:

Knowles places the intercultural companies into four categories: those dedicated to specific cultural communities; those whose main programming originates from “their cultural ‘homelands’”; those (such as African Canadian, Asian Canadian, and Aboriginal) who are internally diverse and produce “new work that speaks across such differences”; and those who are “more broadly intercultural” (74-5). Into the fourth category he places Cahoots Theatre Projects, Modern Times Stage Company, and Nightwood Theatre. Theatrefront, as an extraculturally-focused group who calls Toronto, or at least Canada, home, and that strongly identifies as Canadian, but whose cultural reach is determinedly international, would seem to fit into the wide fourth category (or perhaps a separate fifth category for those with international reach is now worth considering).

13 To suggest that a nation’s theatre uncomplicatedly mirrors— or even distorts/resists—its socio-political changes would be a gross oversimplification. However, to ignore the effects of those changes—to imply that theatre exists in a vacuum—would be equally short sighted. Instead, I am suggesting that while Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) shares with NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) a self-identification with, and an embracing of “risk, innovat[ion] and experiment[ation]” (as Theatrefront’s website announces), as well as an obvious commitment to collaboration, it also signals a third generation—a border-crossing movement. This movement cannot be classified as post-national in the same way that Frank Davey used the term to describe select post-1967 Canadian novels—as depicting “a state invisible to its own citizens, indistinguishable from its fellows, maintained by invisible political forces, and significant mainly through its position within the grid of world-class postcard cities” (266). Rather, it reflects a generation that not only acknowledges its Canadianness (historical and contemporary) as it seeks to discover answers to (or at least to explore) perennial questions of self, national, and theatrical identity, but also employs more indirect, globally-minded collective approaches than its predecessors.

14 Neither Theatrefront’s website nor Daryl Cloran’s introduction to Ubuntu identifies with overt markers of social change. On the website, the group briefly proclaims nationalism: “We are proud Canadian artists [. . .]” and emphasizes its ensemble approach (theatrefront.com). Moreover, the group elaborates upon its intercultural commitment: the claim that they are crossing borders, geographical and artistic, is repeated twice in a short space, and the company places itself in a world context. However, although it aspires to “challenge and inspire,” nothing rings of socio-political change. The mandate is expressed in positive, broad rhetoric. Similarly, in the play’s introduction, Cloran narrates a brief overview of the process and production history: he states that the purpose of the five members of the Toronto ensemble and the four South African actors is “to develop a common theatrical language, to find the meeting point between the two cultures, to learn about ourselves while learning about people from the other side of the world,” and expresses gratitude to Tarragon Theatre for its support of a “ridiculously complicated international endeavour.” He concludes by stating that the play is “a truly international creation that presents the universality of our struggles and the responsibility we all hold to reach out to each other.” His preface is remarkably free of the rhetoric one might expect about such issues as race, politics, and inequality (i-ii). Again, the rhetoric is positive and general, with connotations of harmony that echo an early 1960s utopian vision, perhaps even liberal humanism. Gōmez has cautioned, “Discourses of universality can easily turn into political strategies for powerful groups to perpetuate their power” (4).

15 However, further examination reveals that the relationships Theatrefront has cultivated eschew clear divisions into levels of power, and that the desire for universality need not erase the desire for difference. In a 2011 interview, Cloran states that Theatrefront’s projects focus on difference as well as universality. Gōmez, one will recall, equates the search for the universal with the normative and static and the search for difference with movement and interactivity, and Theatrefront seeks—and stages— movement and interactivity. Theatrefront perceives itself as being “more [about] discovering connections with other performers” than espousing a political agenda. As he emphasizes performativity and cultural growth, Cloran paints a picture of mutual discovery that goes to the roots of theatre and enhances all participants’ sense of what “sets it apart” from other performance, particularly mediated performance—a concern more immediate for theatre practitioners in thetwenty-first century, perhaps, than for preceding generations, given the proliferation of electronic means of sharing performance.

16 The Toronto contingent of Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) built on the experiences of their first collective creation, Return (The Sarajevo Project), in a process Cloran describes as “trial and error” (Interview 2011). They learned, for example, that while having one co-director from each of the participating countries seemed ideal, it wasn’t practical in the end. For both projects, a playwright worked with the collectives, but the position became “nebulous” and evolved to that of scribe or recorder. The writing was “never handed to a single voice [. . .]. Ownership was taken over by the collective.” In the process in South Africa, in a busy, experientially-focused atmosphere where the group posted charts and lists and were surrounded by other visuals and inspirational objects, Cloran saw his job as director as “really focusing it” (Interview 2012). Because each of the collective members was required to undertake a variety of roles, such as acting and creating, each day saw them involved in a series of activities that required use of different parts of the brain. After the first week, when “everything was up for grabs” and the group was becoming acquainted and creating objects, each week became more focused on the play, the arc, and the characters. The Cape Town experience reaffirmed the collective’s commitment to intercultural theatre at the same time as it made them open to other models for future collectives. Intercultural work has proven to be the most artistically stimulating as well as responsible for putting the company “on the map” (Interview 2012).

17 It is imperative to recognize the theatrical history of the South African partner—and of South Africa itself—in this intercultural exchange. As Christopher Balme indicates, from at least the 1970s onwards, companies such as Junction Avenue Theatre Company were committed to multi-racial theatre and experienced in the collective process (119). Mannie Manim, director of the Baxter Theatre Centre in Cape Town in 2004, was, in fact, the senior partner in the Ubuntu collaboration. After about twenty years in technical and administrative positions, Manim co-founded The Market Theatre in 1976, and was instrumental in establishing its international reputation as a co-producer of intercultural theatre, with a remarkable thirty-three international tours in fifteen years (Manim).2 Cloran, aware of Manim’s role as a “pioneer of integration” in attracting international playwrights and companies because of The Market Theatre’s opposition to societal and theatrical segregation, managed to connect with him, specifically through an introduction by South African performers working in Canada. Manim proved influential in introducing Theatrefront to the Cape Town theatrical community, and although Manim didn’t play a day-to-day role in the play’s development, he did “provide dramaturgical guidance” (Interview 2011). Clearly, Manim’s mentoring was invaluable to the young Canadian troupe.

18 Of course, Manim’s work is part of a broader spectrum of important theatrical work in both pre-and post-apartheid South Africa. Furthermore, as Cloran points out, both Sarajevo and South Africa “had a history of social change” (Interview 2011). Therefore, this was no case of uncomplicated appropriation—of the initiator of the exchange acting from a relative position of power and pillaging in an instance of neo-colonialism. As Craig Latrell maintains, “Power is more complicated, localized, and provisional than a simpler victim-victimizer narrative would allow, and to apply this narrative to intercultural transfer (as is frequently done) is to miss the reciprocal essence of these relationships” (53). Theatrefront, a troupe of young, relatively inexperienced professionals from a Western country approached a seasoned, internationally recognized professional from a country with a long theatrical history in a fairly new political and social circumstance. From Cloran’s perspective, “The work for us was to bring the Canadian viewpoint to the table” (Interview 2011). That table was, apparently, well set by The Baxter Theatre. Theatrefront also felt that it was imperative for the play to have “a real tie to the people who created it,” rather than being about one or the other, which indicates a sensitivity to the potential for appropriation by either partner, as well as an apolitical—or at least an emphasis on a personal over a political—perspective.

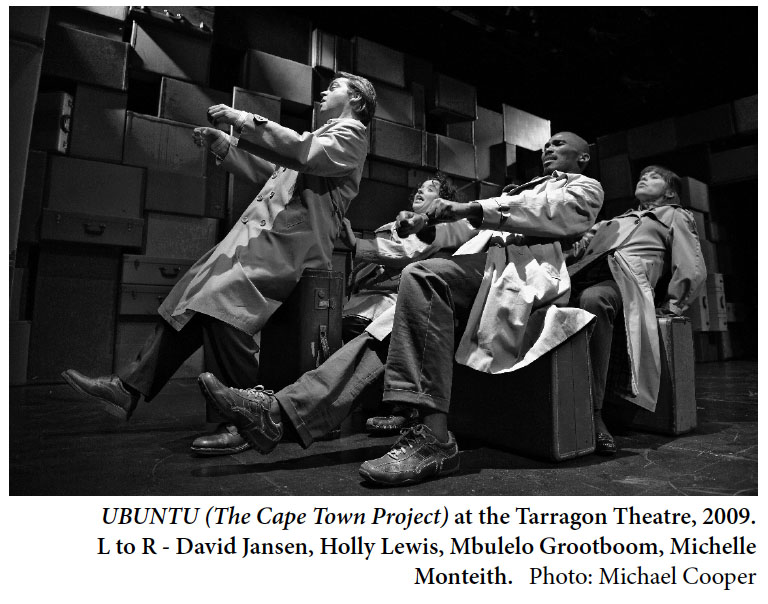

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 119 On the cusp of a vision of a post-apartheid South Africa, Malcolm Purkey, long-time South African artistic director and academic, posed seven questions in speaking of and to “oppositional theatre makers”; the final four are especially pointed in signalling the inevitability and necessity of change:

Can we move from a “protest” to a “post-protest” literature? Can our literature and theatre become proactive rather than reactive?

Can we rethink form and find new content for the new South African theatre? Can we build on the remarkable developments of the last four decades?

How do we prepare to make a theatre that contributes to a post-apartheid society? (156).

Purkey indicates both a rich appreciation for the recent theatrical history of South Africa and a conviction that with a political and social change of such magnitude a theatrical change is necessitated. He also suggests a transition period in post-1994 South Africa, something Manim himself confirmed to have been the case in 2007, when he explained the inclusion of two theatrical classics3 in the Baxter Theatre season: “The theatre of South Africa is really at a turning point. Under apartheid we were a theatre of protest, a theatre of social justice and a theatre with a heavy responsibility. Today, in the post-apartheid period, we have to continue to prove ourselves relevant” (qtd. in Breon).

20 Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) found Theatrefront in the process of creating itself and Baxter Theatre in the process of recreating itself. The former was young and working to establish its identity; members of the latter, with a long combined history of practice in both theatre of protest and international theatre, met with tremendous change and the need to reconfigure identity. Thus, while the collaboration between the groups was intercultural in process and product, it was also, on another level, about an identity exploration that went even deeper than culture. Cloran, in terms free of a larger social agenda, acknowledges that the collaborators sometimes employed terms like “multicultural,” “multidisciplinary,” and “cross cultural,” but insists that they did so “not to proclaim or present a particular viewpoint.” His company, he maintains, is “a politically aware company,” but not one that takes a particular political perspective (Interview 2011). Cloran’s response might be seen to take a narrow perspective on what is a broad term; Augusto Boal, for example, posits that “all theater is necessarily political, because all the activities of man are political and theater is one of them” (ix). However, Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) concerns itself with what are, ostensibly at least, private more than public realm issues and avoids what Filewod calls “the authority of factual evidence” that he sees Canadian drama as historically favouring (Collective 5). Indeed, it could be argued that Theatrefront’s exploration of the shifting nature of scientific notions of truth replaces strategies used in earlier collective creations, which offered revisionist histories and critiques of imperialism. In two scenes in (uncharacteristic) monologue form, Michael lectures to his students about the common ancestry— African—of all humankind and the contemporary reflection of that commonality in Toronto streets, concluding, “For the first time in human history our paths are taking us back towards each other [. . .]. We’re walking home” (73). To return to earlier comparisons, land claims issues and questions of political and social inequality do not take centre stage here, where Michael affirms the conviction behind the play’s title.

21 Christopher Balme defines theatrical syncretism as “the process whereby culturally heterogeneous signs and codes are merged together” (2). As bi- or multicultural, this process “decoloniz[es] the stage, because it utilizes the performance forms of both European and indigenous cultures in a creative recombination of their respective elements, without slavish adherence to one tradition or the other” (2). Theatrical syncretism comes into play in both the process and the production of Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project). As indicated, Theatrefront initiated the project in Cape Town, which was also the site of initial development and a public workshop. The group further developed the project in association with Toronto’s Tarragon Theatre, and its initial productions were at Tarragon and Neptune Theatre in Halifax. Although the majority of the play is set in Toronto, it begins and ends in Cape Town, and its creators and cast reflect similar representation from both countries.

22 Cultural elements, which include South African music and dance, are similarly integral to the play. Balme discusses the tradition of both the township musical and internationally successful work like Mbongeni Ngema’s productions of Sarafina! and Magic at 4 am, noting that music and especially dance can function counter-discursively in syncretic theatre (201). Both do so in Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) as the mainstream Canadian audience is unlikely to have more than passing familiarity with the traditional South African gumboot dance and music elements. However, it is also clear that incorporating these traditional elements inspired the group to make physical and technical innovations. For example, actions often assume dance-like forms, and characters frequently transform into objects; physicality frequently serves as an expressionistic replacement for dialogue in the play. Indeed, Cloran made small but significant modifications to the play for a spring 2012 Western Canada Theatre production in Kamloops and other areas of BC, not in response to a different audience, but as a result of time to reflect on the play. Observing that “[m]ore theatre companies are becoming interested in physical and devised theatre,” Cloran replaced some dialogue-based elements with greater physical reinterpretation (Interview 2011). Whether the intercultural collaboration precipitated or was precipitated by this interest, it has apparently become a hallmark of Theatrefront.

23 The creative recombination is also notable in the spiritual figure of the Sangoma, the Xhosa healer who appears and reappears throughout the play, functioning for much of the play in tension with the scientific bent of Michael. Serving as a potent reminder of the belief that each individual is connected, and therefore has a responsibility, to her/his ancestors, the Sangoma is both a catalyst for much of the play’s action and a connection to the title and central concept of the play. The embodiment of alternative (to scientific and other Western-based) ways of seeing and knowing, the Sangoma is in some senses the play’s spiritual centre and wellspring—and, like the music and dance, a challenge to dominant Western theatrical conventions. However, as discussed earlier, the play ultimately rejects binaries; in the second-to-last scene, Michael declares, “Our cities are the new savannahs and we’re evolving to suit them; but black or white, we’re all Homo urbanus” (72). Moreover, its last scene may be read as a passing of the torch from the elderly Sangoma to Jabba and a subsequent acceptance of two traditions—a success from the Sangoma’s perspective because harmony and connectivity are re-established.

24 Both Balme and Gōmez insist that intercultural elements, when de-contextualized, are recoded but not stripped of their meanings or smoothly homogenized into the larger work. Gōmez advocates acceptance of difference: “The point is, precisely, not to transcend the difficulty in decoding the cultural code” (41); Balme advocates “a consciously sought-after creative tension between the meanings engendered by these texts in the traditional performative context and the new function within a Western dramaturgical framework” (5). Like the music, dance, and Sangoma, the extensive use of the Xhosa language is a significant counterdiscursive element. Although the text of the play provides English translation, the production does not. Code switching is at once inclusive and exclusive. Examining its functions in three Chicano plays, Carla Jonsson concludes that it “can be used to add emphasis to a certain word or passage, to add another level of meaning, to deepen/intensify a meaning, to clarify and to evoke richer images, to instruct the audience about a particular concept, to attempt a more faithful representation of the voice of someone else, to mark closeness, familiarity, to emphasize bonds, and to include or, on the contrary, to mark distance, break bonds and exclude” (1309). Of course, the effect of code switching on the stage is subjective, even beyond primary considerations of language fluency. However, in Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project), it clearly functions as both an introduction to (for many English-language speakers), and an affirmation of, the non-dominant language of the play, as well as a device likely to encourage a sensory transfer from aural to visual for at least some. Regardless of the range of responses to code switching, it is, as Balme states, “a theatrico-semiotic process comparable to the recoding of dances, songs, or rituals” and evidence of “the polyglottal stage” of syncretic theatre (110). This stage was all the more complex in Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) because, Cloran states, “Xhosa is not really a written language; the oral had to be approximated in writing” (Interview 2011). In tandem with the other Xhosa cultural elements, the code switching makes the play an intriguing, and, to some extent, elusive hybrid, particularly as crucial parts of the play, including the resolution, are in Xhosa, and thus require English-speaking audiences to rely on movement for interpretation.

25 In 2012, following a successful Western Canadian tour of the play, Cloran responded with a clear appreciation for Balme’s “creative tension,” when asked to articulate the most important lesson Theatrefront gleaned from the collaboration in Cape Town: “While we were building the production, the Canadian impulse was often to sit down and write a text-based scene, while the South African performers always wanted to get up and explore story and character through movement and physicality. These images and scenes became the most striking moments of the play.” Canadian audiences found these scenes and the Xhosa language demanding, challenging, and, ultimately more rewarding and memorable.4 Thus, in a sense, they replicated the process of creation and discovery of the play itself. Cloran reflects, “We chose to work with artists from other countries to challenge ourselves and our artistic process […]. We were excited to learn that audiences wanted to be challenged as well” (Interview 2012).

26 In its experimental form and celebration of difference, Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) is an example of extracultural theatre that not only exposed its creators to “universals” of theatre through interaction but also introduced mainstream Canadian audiences to South African culture without diluting its Xhosa elements. NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) and Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) reflect the development of collective creation as a response to different and increasingly multi-faceted stages of both national and theatrical development. As Bruce Barton observes, “increasing diversity in terms of artist intentions and increasing complexity in terms of critical response” is responsible for the movement in both Canadian theatrical practice and scholarship explored in this paper: “from nationalism to multiculturalism to interculturalism and internationalism” (ix). Marc Maufort’s reflections in a comparative study of several hybrid Aboriginal plays from Canada and Australasia are also germane to this paper, particularly his recommendation for alternative Western and Native lenses. Similarly, South African scholarly lenses on Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) would yield welcome and, likely, diverse perspectives. In addition, Maufort encourages critical acknowledgement of “the provisional rather than totalizing nature of the conclusions reached” (107). The ephemerality at the base of theatre, the complexities of the collaborative process, and the particularly knotty circumstances of intercultural endeavours must be recognized.

27 David O’Donnell’s “Quoting the ‘Other’: Intertextuality and Indigeneity in Pacific Theatre” explores recent works that transcend the boundaries of resistant texts and coloniser/indigenous oppositional boundaries in order to “allow texts to speak to each other, deconstructing the oppositional framework of postcolonial debates and opening up new possibilities for dramatic representation” (131). Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) similarly eschews simplistic oppositions. Although it does not overtly re-cast canonical Western plays, deconstruct Western anthropological notions in any extended fashion, or intermingle direct quotation of Hollywood cinema with traditional spirituality (as the plays O’Donnell examines do), it does speak to Canadian theatre history in its own somewhat oblique but nonetheless strong way. Although it does not speak to its antecedents in the direct way that, for example, Michael Healey’s The Drawer Boy speaks to (indeed, to some extent recreates) the canonical Canadian collective creation, The Farm Show, Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) is an heir to and an extension of them. In fact, Cloran acknowledges, “We’re very aware that collective creation is a Canadian tradition. Paul Thompson’s The Farm Show shaped my understanding of collectives” (Interview 2011). Filewod encapsulates the legacy of first-generation collective creation: “Collective creation made it possible for actors to find indigenous models of performance, and to explore personal (often romanticized) responses to the sources of Canadian culture” (Collective 22).

28 Although the Canadian contingent of the creators of Ubuntu (The Cape Town Project) consciously sought and found performance models beyond Canadian borders, Canadian models informed their work and the intercultural project also renewed their interest in Canadian culture and history. Theatrefront reveals that concerns about Canadian identity continue to be relevant for new generations: the process of creating Ubuntu “evoked a lot of questions regarding Canadian identity” (Interview 2011). Indeed, Cloran credits it with “feeding” the creation of the company’s next work, The Mill, a Gothic, four-part exploration of Canadian identity through Canadian history connected by an Ontario mill. Part Three: The Woods scrutinizes our history through a plot in which settlers propose construction of the mill on the site of a First Nations burial ground. Written by Tara Beagan, who is of Ntlaka’pamux (Thompson River Salish) and Irish Canadian heritage, Part Three: The Woods, like NO’XYA’ (Our Footprints) centres on land disputes that have contemporary resonance. Like 1837: The Farmers’ Revolt, The Mill revisions Canadian history through a present lens. It is a reflection of our complex, globalized contemporary environment that an “exploration of home” emerged from Theatrefront’s initial exploration of geographically distant places like Sarajevo and South Africa.