Article

To Be Dub, Female and Black:

Towards a Womban-Centred Afro-Caribbean Diasporic Performance Aesthetic in Toronto1

This essay traces the contributions of Afro-Caribbean women, particularly Rhoma Spencer, ahdri zhina mandiela, and d’bi.young anitafrika, to a developing performance aesthetic in Toronto that is grounded in Caribbean cultural texts. It focuses on ways in which the work of these women has consciously challenged and queered Canadian and Caribbean theatrical and performance forms as well as heterosexist and masculinist cultural nationalisms and colonial modernities. Spencer, through her company Theatre Archipelago, employs a “poor theatre” aesthetic, a presentational sensibility, exhuberant performances, and a richness of language, all grounded in Caribbean traditions such as carnival, ’mas, and calypso, to speak in complex ways about the politics of class, gender, and race with a clear emphasis on women. mandiela, through her company bcurrent and especially through her plays dark diaspora…in dub! and who knew grannie, has invented and developed a new form, dub theatre, out of the Jamaican-based traditions of dub poetry. d’bi.young anitafrika has followed in mandiela’s footsteps, contributing to the women’s dub tradition through the invention of what she calls “biomyth monodrama” as exemplified in her sankofa trilogy. These women have constituted a Toronto within the city that functions as a transformative space operating at the intersection of nations, sexualities, and performance forms to queer traditional theatrical hierarchies, together with the largely masculinist ethos of much Caribbean performance and the narrow chronopolitics of modernist colonial “development.” They have created and continue to develop entirely new, empowering, “womban-centered,” and “revolushunary” Afro-Caribbean forms that are (re)grounded in traditions of the grannies, the griots, the nation languages of the people, and movement and language that emerge from and celebrate Black women’s bodies in a transnational Canadian-Caribbean diaspora.

Cet article retrace les contributions des artistes afro-caribéennes Rhoma Spencer, ahdri zhina mandiela et d’bi.young anitafrika à la création d’une esthétique de la performance à Toronto, fondée sur des textes issus de la culture caribéenne. Il s’intéresse aux façons dont le travail de ces femmes a remis en question les formes du théâtre et du spectacle au Canada et dans les Caraïbes, de même que les nationalismes culturels hétérosexistes et masculinistes ainsi que les modernités coloniales, en y inscrivant une sensibilité homosexuelle. Avec sa compagnie Theatre Archipelago, Spencer emploie l’esthétique du « théâtre pauvre », une sensibilité aiguisée aux divers aspects de la présentation, un jeu exubérant et une langue riche qui prennent appui sur des traditions caribéennes comme le carnaval, les festivités de Noël et le calypso pour traiter de manière complexe de la lutte des classes, des sexes et des races, en accordant une importance marquée aux femmes. mandiela, avec sa compagnie bcurrent et surtout dans ses pièces dark diaspora…in dub! et who knew grannie, a créé et perfectionné une nouvelle forme, le théâtre dub, en partant de la tradition poétique jamaïcaine, la poésie dub. Suivant l’exemple de mandiela, d’bi.young anitafrika a participé à la tradition dub au féminin en inventant ce qu’elle a appelé le « monodrame du biomythe », un style qu’illustre sa sankofa trilogy. Ces femmes ont créé au sein de Toronto un espace de transformation à la croisée des nations, des sexualités et des formes spectaculaires qui sert à donner un caractère homosexuel aux hiérarchies traditionnelles du théâtre, à l’éthos principalement masculiniste du spectaculaire caribéen en général et à la chronopolitique étroite du « développement » moderniste colonial. Elles ont créé, et continuent de créer, des formes tout à fait nouvelles, « révolushionnaires » et centrées sur la femme, qui servent à pousser plus loin son émancipation. Ces formes afro-caribbéennes (re)prennent racine dans les traditions des grands-mères, des griots, des languages nationaux du peuple, des mouvements et des langues qui, au sein d’une diaspora canado-caribéenne transnationale, émergent du corps des femmes noires et le célèbrent.

1 African Canadian Theatre is distinct from Black theatre as it has developed in the US, the UK, and elsewhere in the African diaspora, in part because of a “nativist” or nationalist strain which locates itself largely in Nova Scotia, and in part because of the influence of a broadly diasporic sensibility introduced by a more recent urban immigrant community.2 In Toronto a large part of the distinctiveness of African Canadian theatre has to do with the contributions of immigrant women from the Caribbean, many of them queer-identified, including centrally the early work of Vera Cudjoe, the subsequent contributions of Rhoma Spencer, and the dub-based work of ahdri zhina mandiela and d’bi.young anitafrika that I wish to explore here. Building on Cudjoe’s foundations, each of Spencer, mandiela, and young anitafrika has consciously challenged received Canadian and Caribbean theatrical and performance forms, as well as heterosexist and masculinist cultural nationalisms and colonial modernities, by developing woman-centered Afro-Caribbean diasporic performance aesthetics rooted in island traditions but grounded in Canadian realities. What these women have done is to constitute Toronto, already one of the most culturally diverse cities in the world, as heterotopic,3 transformative space within which they can work at the intersection of nations, sexualities, and performance forms. That is, they have constituted the city as a space that enables them at once to womanize and queer “the revolushun,” building on Caribbean performance practices such as carnival, ’mas (masquerade), calypso, pantomime, satirical musical reviews, agit prop, and, crucially, dub, to create expansive new performance forms and theatrical hybridities in diasporic space.

2 Although Black theatre in Canada has a history dating back to at least 1849 (see Breon, “Black,” and “Growth”; Saddlemyer 14; Sears iv), the first professional theatres were an outgrowth of a wave of immigration from the West Indies that began in the 1960s. In Toronto, the first of these companies, Black Theatre Canada (BTC), was founded by a Trinidadian immigrant woman, Vera Cudjoe, in 1973.4 BTC was unapologetically Caribbean from the outset, and, although it staged such work as Lorraine Hansberry’s iconic African American play A Raisin in the Sun in 1978, under Cudjoe it was also dedicated to the early development of an Afro-Caribbean Canadian performance aesthetic. This commitment manifested itself in the production of plays by Caribbean writers such as Trevor Rhone, Roderick Walcott, Daniel Caudieron, and Mustapha Matura, and in the bringing to Toronto of major Caribbean performers such as Paul Keens Douglas and, crucially, Louise (“Miss Lou”) Bennett. In these ways BTC introduced and exposed the community to AfroCaribbean performance forms and languages that were to have a powerful influence on new work developed by the company itself and by many others in subsequent years, including Spencer, mandiela, and young anitafrika. “Miss Lou,” in particular, was crucial, in that her published and performed poetry legitimized the popular “nation language” of Jamaica on which dub poetry came to be based—the rich African-influenced creolized language spoken by the descendants of slaves, labourers, and servants of the colonizer that had hitherto been denigrated as substandard English. Bennett lived for a number of years in Toronto, and her work was crucial to the development of the city’s Caribbean community and its art forms. BTC also made direct contributions to the cultivation of an Afro-Caribbean diasporic dramaturgy by developing such things as playwright Amah Harris’s school-touring Anansi Tales beginning in 1977, structured by the stories and rhythms of African folk tales (Gingell, “jumping”11n12), and by producing the award-winning “Caribbean” Midsummer Night’s Dream, directed by Azra Francis in 1983 and structured by the rhythms of carnival, ’mas, and calypso.5

3 BTC folded in 1988, but over its fifteen years it had helped to develop a generation of Black theatre artists, predominantly of Caribbean origins, who would lead the way in subsequent years, alumni who included Amah Harris, whose Theatre in the Rough focused much of its efforts on training Black youth through its hugely influential “Fresh Arts” program, alumni of which in turn include d’bi.young anitafrika. Neither BTC nor Theatre in the Rough were revolutionary in their politics, or even in their aesthetic experimentation, but both paved the way, though exposure to African and Caribbean storytelling and performance forms, through mentorships and training, and through the validation of Caribbean “cultural texts,”6 for the more radical experimentation that was undertaken by their alumni and successors over subsequent decades.

4 Toronto is now home to four major continuing Black theatre companies,7 the earliest of which to emerge, b current, being the most direct descendent of BTC. b current was founded in 1991 by Jamaican-born BTC alumna ahdri zhina mandiela to nurture exploration, engage community, and develop talent that reflects the aesthetics, language, and speech of the Black diaspora. mandiela says that BTC was “how I got hooked on the scene here” (Knowles), and in many ways mandiela inherited the mantle of Vera Cujdoe both in terms of her mentoring role, particularly for women, and her (more radical) exploration of Caribbean performance forms. In 1998 her company mounted its first “raiZ’n the sun” ensemble training program of workshops and classes for young career-oriented artists, and in 2001/2 it launched its annual “rock.paper.sistahs” festival because, according to mandiela in an interview with Toronto’s gay and lesbian weekly, Xtra, “I needed a forum within the company where we could do some unconventional presentation of work, particularly by sisters.[…] Shorts, experimentations, out-on-a-wire stylistic wrangling, where it wasn’t just productions as usual” (qtd. in Alland). Broadly diasporic in mandate, the company nevertheless began with a Caribbean, Jamaican-based form, dub poetry, and with a landmark production of mandiela’s own dark diaspora…in dub, of which more below. It also launched the Canadian careers of many key Afro-Caribbean artists, most notably d’bi.young anitafrika—then debbie young—and Rhoma Spencer.

5 Indeed, the most recently formed African Canadian company now operating in Toronto grew directly out of the 2004 edition of rock.paper.sistahs. In 2005 Trinidad-born Rhoma Spencer turned two one-woman one-acts mounted there into the first production of her own company, Theatre Archipelago: Jamaican Honor Ford-Smith’s “Just Jazz” (an adaptation of Dominican writer Jean Rhys’s Let Them Call It Jazz) and Spencer’s own “Mad Miss” (an adaptation of Jamaican-born Canadian Olive Senior’s You Think I’m Mad Miss?). Archipelago, named of course for the Caribbean archipelago, is dedicated to serving “as a catalyst for propagating Caribbean theatre in the diaspora” and staging plays “by Canadian and Caribbean playwrights at home and abroad” (Theatre Archipelago).8 Its productions, frequently co-produced with b current, have been dominated by plays by and/or about women.

6 Like mandiela, Spencer is interested in the discovery and development of a uniquely Afro-Caribbean diasporic aesthetic. For Spencer—and I believe this is crucial for each of the women I am discussing—Caribbean (as opposed to island-specific) culture only exists in diaspora (see Knowles) and a Caribbean aesthetic is at once fundamentally African and globally hybrid—what Tobago playwright Tony Hall calls “creolization, hybridity, betweenity and assimilation” (qtd. in Citron). But this diasporic space is enabling for Spencer in part because it is more possible for her, as a woman, to direct in Toronto—“back in the Caribbean, theatre seemed to be a man’s space” (qtd. in Knowles)9 —and because Toronto is also broadly constituted as queer. In an interview in Xtra in March 2011, Spencer explains that part of the draw of Toronto for her was that “I was aware of the black lesbian movement taking place in the city, and I felt like I wanted to be part of it…. When you come from a space where you have to hide who you are, coming to Toronto is an awakening” (Dupuis). Spencer, then, deeply critical of Canadian multiculturalism,10 is nevertheless consciously using Toronto as a heterotopic, enablingly queer and female space for the development of transformative panCaribbean diasporic performance forms, and her work extends that of BTC in its explorations of carnival, ’mas, and calypso. Indeed, the company participated prominently in the 2011 Scotiabank Caribbean carnival (formerly “Caribana”), presenting original “Jouvay” (“jour ouvert,” or opening of the first day of Carnival) ’mas characters and costumes in the carnival parade for the first time in its forty-four year history (see Merringer), and reintroducing the political critique inherent in carnival, but suppressed in the early years of the festival.

7 Archipelago’s mainstage productions have been equally political and have equally drawn upon and developed Caribbean forms in a Canadian setting. On some occasions this has meant producing Caribbean plays such as Trinidadian Tony Hall’s Twilight Café in 2007, or the Groundwork Collective of Jamaica’s Fallen Angel and the Devil Concubine in 2006,11 the latter brilliantly transported by its director, mandiela, to Toronto’s diverse Parkdale neighbourhood and making provocative use of crosscasting. But Archipelago has also developed new work by Caribbean Canadians, such as Haitian Canadian Edwige JeanPierre’s Our Lady of Spills in 2009, the story of an elderly white woman and her Black caregiver. All of the company’s work is characterized by a “poor-theatre” aesthetic, a presentational sensibility, exuberant performances, and a richness of language that are typical of Caribbean theatre, and all speak in complex ways about the politics of class, gender, and race, with a clear emphasis on women.

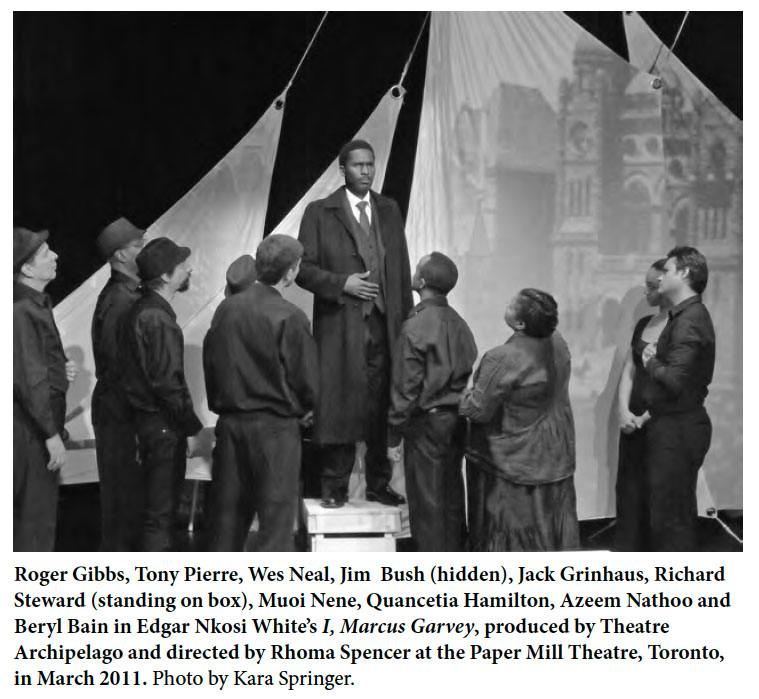

8 The company’s evolving aesthetic may be seen to have crystalized in the 2011 North American premiere production of Monserrat born Edgar Nkosi White’s I Marcus Garvey, directed by Spencer and co-produced with b current. In telling the politically charged biography of the great Jamaican Black nationalist and pan-Africanist leader, Spencer used a mélange of mostly presentational styles, using a stripped-down set that thrust the action forward to the audience, extensive doubling, choral speech and movement, direct address, comic exaggeration, and a generally carnivalesque atmosphere that was greatly assisted by the presence of an on-stage five-piece band that occasionally joined in the action, feeding the call-and-response and swelling the crowd scenes. In an interview for the Caribbean scholarly journal Macomère, ahdri zhina mandiela identifies “having a whole lot of show going on” as “part of our Caribbean aesthetic” (Knowles), and Theatre Archipelago’s production of I Marcus Garvey exemplified the style.

9 But it is Spencer’s mentor at b current, ahdri zhina mandiela, who has been responsible for the invention and naming of the first unique and identifiable Afro-Caribbean diasporic performance form in Canadian theatre. With her 1991 show dark diaspora…in dub!, subtitled “a dub theatre piece,” mandiela not only launched b current, but forged a new form, not out of carnival, ’mas, or calypso, but out of her own political and poetic practice as a dub poet.12 Dub poetry emerged in the 1970s and 80s in Jamaica out of the practice of MCs, or “toasters,” talking over the “dub,” or instrumental side of reggae recordings, where the songs were stripped to their bare, rhythmic essentials and used as dance tracks. The rhythm-driven, embodied, and performance-based poetic form that emerged from this was deeply influenced by the revolutionary and celebratory Black politics, practice, and popularity of Bob Marley and Louise (“Miss Lou”) Bennett,13 their bringing into respectability of Jamaican, or “nation language,” and Marley’s Rastafarianism.14 As dub developed and spread globally in the 1980s, the three international centres where it most flourished were Kingston, Jamaica, London, England, and, notably, Toronto (see Allen 16), where, partly because of the developing feminist scene in the city, many of the form’s leading practitioners have been women. And many of these women—including Lillian Allen, Afua Cooper, Motion (Wendy Braithwaite), Dee (Deanne Smith), amuna baraka-clarke, and d’bi.young (see Knopf)—have either womanized or queered the dub form itself, in reaction to its mainly masculinist roots. Included prominently among these artists is ahdri zhina mandiela herself, whose early, 1985 volume Speshul Rekwes (“special request”) includes distinctly womanist poems such as “young girls on the street” (12-16), “ooman gittup” (38), and especially “black ooman” (41-41). Although many since the 80s have rejected the term “dub poetry,” preferring the more expansive terms “performance poetry” or “spoken word,”15 others feel that these later rubrics for an already expansive form strip dub of its politics, its roots in class, race, resistance, and empowerment,16 its distinctly Caribbean lineage, and its ties to the nation languages of the archipelago. As Carolyn Cooper argues, “when ‘dub’ poetry is dubbed ‘performance’ poetry it goes genteelly up market” (81).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 110 And it is interesting that from the beginning, partly because of the overwhelming influence of Louise Bennett, and evident in the work of early practitioners such as Faybienne Miranda, Lillian Allen (whose 1993 collection of poems was called Women Do This Every Day), and Jean Binta Breeze, dub has been amenable to women who brought to it “new agendas and new voices, different sounds and riddims” (Afua Cooper, “Utterances” 2). Dub, then, has succeeded in avoiding or derailing some of the masculinist— indeed misogynist—aura of much rap and hip hop. mandiela herself, noting the expansion of meaning of “dub poet” beyond its original reggae “base” and its increasing use of standard or Black American English, prefers to call herself a “dub aatist” (qtd. in Gingell, “jumping” 10): “for me, anything that works against the concept of nation language is a negative” (qtd. in Gingell, “jumping” 7). A large part of the importance of dub poetry for mandiela is that it “bridges traditional and contemporary experience,” it “exists as both old and new” and therefore has the potential to become part of what she calls “classical black orality” (qtd. in Lee 7) while also advancing the politics and poetics of dub into a more broadly diverse and inclusive future.

11 In adapting dub for the stage, mandiela was influenced by distinctly womanist African American playwright and poet ntosake shange’s legendary “choreopoem,” for coloured girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, and by African traditions of call and response (already incorporated into much dub poetry).17dark diaspora consists, as script, of a series of dub poems that “explores the present day psyche of the black diaspora,” spanning “some 30 years of (social/political/economic) events and emotion influencing the psychological make-up of the black psyche as evidenced in a black woman’s journey in 1990s Canada” (mandiela, “about” vii). “In creating ‘dark diaspora…in dub,’” mandiela writes, “the aim was to expand the literary tradition of dub poetry—by producing an integrated stage script composed entirely from dub poems—as well as to present a totally new stage experience: dub theatre” (mandiela, “evolution” x). “By working with a dub aesthetic,” as Loretta Collins argues, mandiela

The resulting show, located in a generative diasporic space, Collins argues, “generate[s] a vertical velocity with the fluidity of a deejay’s wizardry at the sound system controls” (46).18 And as Rinaldo Walcott asserts, that velocity, fluidity, and movement are evocative of forced and other migrations undergone by Black people globally since the middle passage. As such, they are fundamentally “[characteristic] of Black diasporic consciousness” and form “the bases of a diasporic aesthetics” (“Dramatic” 100). Walcott’s insight is important and has implications beyond dark diaspora itself. What the play exemplifies is the ways in which travelling between mixed and multiple forms, styles, and sign systems captures and asserts resistant creative control over the often involuntary migration experiences that have characterized Black diasporic life—including the life of mandiela herself and the lives of Vera Cudjoe, Rhoma Spencer, d’bi.young anitafrika.

12 But in bringing dub to the stage through women’s bodies, the play also womanized a Caribbean form that, grounded in competition and virtuosic display, had been overwhelmingly masculinist. The play is also and crucially, as mandiela says (evoking lesbian womanist Audre Lorde’s term “biomythography”19), “automythobiographical” (mandiela, “evolution” x, emphasis added). “Biomythography, together with its variants, is a fundamentally womanist form, and in the workshops and productions of dark diaspora mandiela herself played the central autobiographical role as ‘poet maestra’” (Cooper 444).20 The staging involved no less than seven women in its first production, directed by mandiela and Djanet Sears, six of them serving as dancers and “chanters,” and the published script in one suggested staging calls for as many as fifteen to fifty women as “voice/shape/sound.” In each option, however, in addition to the dub poetry at its core, “mandiela used sound, riddims, movement, dance, the spoken word, and [women’s] textile art” in what Afua Cooper has called “truly an integrated script” (444).

one

of many/million

dark tales (mandiela, dark 3)—

treats materials that range from personal longings as a lover, as a “sistah,” as a black woman in Canada, through laments about the real and metaphorical coldness of Canada—including Canadian “just/ice” (34)—, to sequences addressing diasporic issues such as immigration and exploitation, returning home, the neo-colonialism of bauxite mining in Jamaica, whiteness, racism, Black politics, resistance, and solidarity. And it evokes love between women throughout, most explicitly in the poem about bisexuality, “who is my lover, now?”—

moan in the recess of my desires

peaking obsessions

in the basal drops of dark sticky tones

this sister sounds/

slide past my throat

unto the lifesongs I peal

she is your lover? now (8)—

creating, again, an expansive and creatively queer space within the diaspora, and ending with the assertion “black/woman.i.be” (8). As Afua Cooper says,

The show ends with seven strong Black women onstage

chanting arms

chanting arms

chanting (53)

13 The central contributions of dark diaspora in dub to a developing Afro-Caribbean diasporic aesthetic, then, are to build upon the heterogeneity and carnivalesque hybridity of existing Caribbean and Caribbean Canadian theatrical forms by introducing into the mix the language and politics of dub poetry, “womanized” through the admixture of automythobiography and embodiment in the choreographed movement of powerful Black women’s bodies.

14 In the 1990s, as she ran b current and mentored a generation of Black women in Toronto, mandiela found herself and her collaborators21 at the centre of what she calls “an africanadian theatre aesthetic trek” that continues to this day (“africanadian” 69). The trek has taken her backward, to re-explore her own roots in such things as Jamaican pantomime—which she calls “my biggest influence” (Knowles)—, miss lou and ’mas ran (Louise Bennett and Rannie Williams), Lorraine Hansberry, ntozake shange, Vinette Carroll, and the early dub poets (mandiela, “africanadian” 69-70; Knowles; Gingell, “jumping”; Collins). But the trek has also taken her forward into “the grunt work of carving out a fresh aesthetic… a fresh concoction of styles and form, as well as uniquely Canadian content” (mandiela, “africanadian” 70)—one that, she acknowledges elsewhere, is “woman-centric” (Knowles), if also expansive and inclusive in the ways that the term “queer” itself is expansive:

“[F]or black people/peoples of african descent,” she argues, “our experiences & the way we deal with them are rooted in our blackness/our afrikanness—the ways we talk/celebrate/fight/desecrate/consecrate/rejuvenate—these are elements which determine what our art looks & feels like.” mandiela’s “africanadian aesthetic trek,” then, “meant searching & developing beyond form & content; toting styles which may be unfamiliar in theatre, but are familiar in other forms of black art” (qtd. in Lee 4). Much of mandiela’s work as a director in the decades since dark diaspora has involved “toting” such styles and introducing such “other forms of black art” to the stage, including, in addition to poetic text: music, dance, textile arts, visual arts, games, oratory, and elements of “ring shout” and call-and-response forms of expression,22 and she has carried this through to her own writing for the stage.

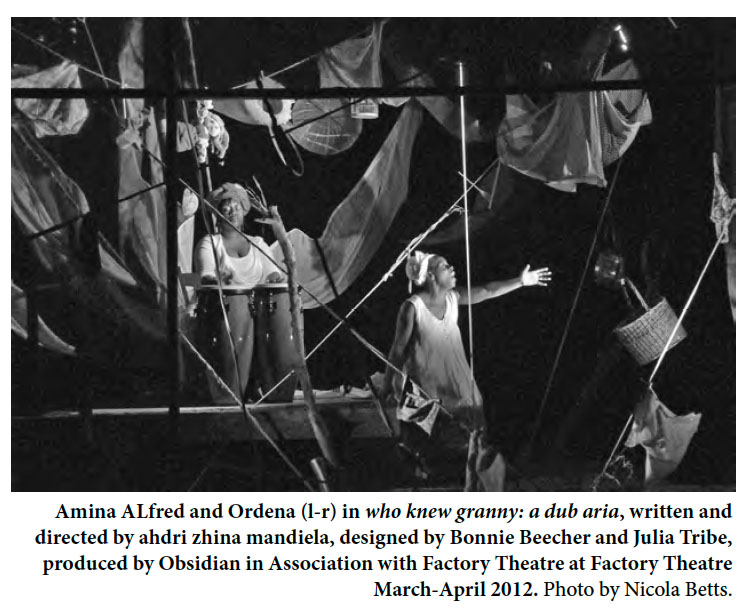

15 If dark diaspora was the starting point in her trek as a playwright—and she admits to not having written for five years after it was produced while focusing on lobbying for and running her company and its programs (Process Panel), and at one point to having contemplated leaving theatre for the film world, where she is also active (“africanadian” 69)—the next major nodal point in her own writing for the stage came almost twenty years later in March 2010 when she directed the premiere production by Obsidian Theatre of her new work, who knew grannie.23 The play is subtitled, “a dub aria in several movements [as opposed to scenes] signifying on24family ties vested in a generation of cousins each attempting to hold onto themselves all the while celebrating/ mourning/transporting/grasping/saying so long grannie/forever/in their hearts.” On the title page of the unpublished script mandiela defines a dub aria as “an emotional flight usually done in a single melodic voice.” But the single melodic voice is not that of a solo autobiographical subject, or even a single “character.” There are continuities with the automythobiography of dark diaspora, but one major step in the development of her particular dub theatre aesthetic taken by who knew grannie is to move it out of the consciousness of a single character. Here there are not only five voices heard, but those voices are spoken out of the bodies of five distinct characters, though a woman, the titular, recently deceased grannie, remains central, and mandiela maintains that the play “bring[s] several characters in one voice through a single journey” (Program). grannie lives and dies in Jamaica, but after her death her four grandchildren are called together from the four major centres of the transnational dub diaspora: kris, now 23, is a queer male celebrity chef in the US; likklebit, now 29, is a teacher in, and recent immigrant to, Canada; tyetye, now 37, is a musician stuck in prison in the UK; and vilma, now 39, is a respected politician “at home” in Kingston.

16 Like mandiela in her aesthetic trek, and like the sankofa bird that is the play’s central symbol and cultural text, who knew grannie looks both backward and forward. After a brief “overture” that introduces the cousins, grannie is organized into fourteen musical “movements” and structured around seven Jamaican children’s games: “children children,” “bull in a pen,” “chick chick chick,” “redlite,” “rockstone/manuel rd,” “show me a motion,” and “what’s the time, mr wolf” (2), all of which position the children as children, answering call-and-response style—or in one instance, “no call, just response” (26)—to grannie’s reiterated invocation, “children children.” Indeed it is grannie’s calling—her vocation and her invocation—“to bring the grown children back in tune with themselves” (4). She does this explicitly by taking them back to their childhood and reminding them through her teachings to “walk good” (41), and by invoking, indeed imitating and embodying, sankofa. Sankofa is a crow-like bird of West African myth that flies forward while looking back and taking an egg (the future) off of its back; it teaches that we must go back to our roots in order to advance. The bird is pictured on the show’s poster and program, where the egg consists of a circle of black children’s joined hands.

17 In performance who knew grannie was deeply moving, mellower than dark diaspora in its politics but equally rich in resonance and reference, and incorporating an increasingly rich blend of styles and performance genres. It was located on what one reviewer called a “cat’s cradle of a set” (Bradshaw) with a scattered diasporic foreground linked together by brightly coloured strands and backed upstage by grannie’s warm and bright Jamaican hearth, from which the show’s live Jamaican music emanated and to which the cousins returned. The show ends with the return complete—“sankofa now”—as grannie signifies on “swing low, sweet chariot,”25 and the children urge her to

kris: with sweet cocoa tea

tyetye: and bush mint

vilma: with a river bursting off rain (41-2),

and to “walk good.” Grannie “caaaaawww…caaaaaaww”s, “the sankofa crow continues” and the solo Jamaican nyabinghi drums (42).26

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 218 who knew grannie’s use of multiple voices, live music, stylized movement, evocative call-and-response exchanges, its resonant use of signifying tropes central to pan-African cultures, its formal, “dub aria” structure, and its embodiment of sankofa, all significantly enrich mandiela’s developing dub theatre aesthetic. The play’s expansiveness, generosity of spirit, and connection to community are exemplary and are representative of the way the form has developed in the work of her widely successful protégé, the Jamaican born d’bi.young anitafrika (“young” after her father, “anita” after her mother, anita stewart, a pioneering dub poet in Jamaica, and “afrika” after, well, Africa).

19 young anitafrika identifies as “a black, queer, African Jamaican, Canadian, Caribbean mother” (Luhning 11), and she argues significantly that her queerness and “feminist analysis” are both part of her “Canadian reality” within diasporic space:

young anitafrika’s work grows directly out of mandiela’s, making still more explicit the woman- (or for young “womban”-) centeredness of mandiela’s work from dark diaspora through the rock.paper.sistahs festival to who knew grannie.27 It adopts, adapts, extends, and explicitly queers her dub aesthetic. Some have read the “’bi” in “d’bi” as an assertion of her bisexuality, and young anitafrika welcomes the interpretation, appearing on the cover of the gay and lesbian Xtra as a way of explicitly challenging homophobia in the Caribbean community and layering dub, as she says, with her “heavy feminist rhetoric” (Flynn and Marrast 42, 46). Finally, young anitafrika re-adapts mandiela’s “automythobiographical” to “biomyth monodrama,” a subtitle that has replaced “dub theatre” for all of her recent plays.

20 But it is clear that young’s roots are in dub: her practice grows directly out of that of her mother, and she is a published and recorded dub poet. All of her early work as a playwright was billed as dub theatre, including two early two-person plays, yagayah: two.womyn.black.griots (2001, co-authored and performed as “debbie young” with naila belvett—now naila keleta mae), and androgyne (2004-07), that are the most explicitly queer of her work. Both plays bring to the dub theatre aesthetic a new, positive exploration of transgressive Black female sexuality. Indeed, both plays, as Andrea Davis argues of yagayah (which was directed by mandiela), directly treat Black female sexuality as a bridge between Canada and the Caribbean (Davis 116-19), and this element is characteristic, if not always so explicitly, of all of her work. young anitafrika’s work has also continued to be deeply steeped in a dub tradition, and it is striking how much of it builds upon and directly echoes that of mandiela: the use of sankofa, of children’s games, of grannie’s “children children” summons, and so on. As her work has evolved, however, young anitafrika has increasingly come to think of what she does less as dub theatre than, overarchingly, “storytelling,” but more specifically for her theatre work, “biomyth monodrama,” evoking Audre Lorde and, again, mandiela’s automythobiography.” Young defines “biomyth” as

“biomyth monodrama,” then, is “a mythologized auto-biographical play told by the story’s creator/performer” (Email).

21 As she has worked, particularly on her now complete major trilogy, the three faces of mugdu sankofa, she has been at once focusing on single-actor, multiple-character work, and working out what she now calls “the sorplusi method.” She began theorizing her practice through the four principles of dub poetry taught to her by her mother: “rhythm, political content, language, and orality” (Luhning 12).28 To these she first added sacredness, integrity, and urgency (“because my own spirit wants to move towards a place of negotiating what it means to be a revolutionary” (Luhning 12)), and eventually one more, inventing the acronym “sorplusi” (standing for self-knowledge, orality, rhythm, political content and context, language, urgency, sacred- ness, and integrity). “these ideas,” she argues,

22 At her anitafrika studio in Toronto and at the pan afrikan performing arts institute training program that she now runs in South Africa,29

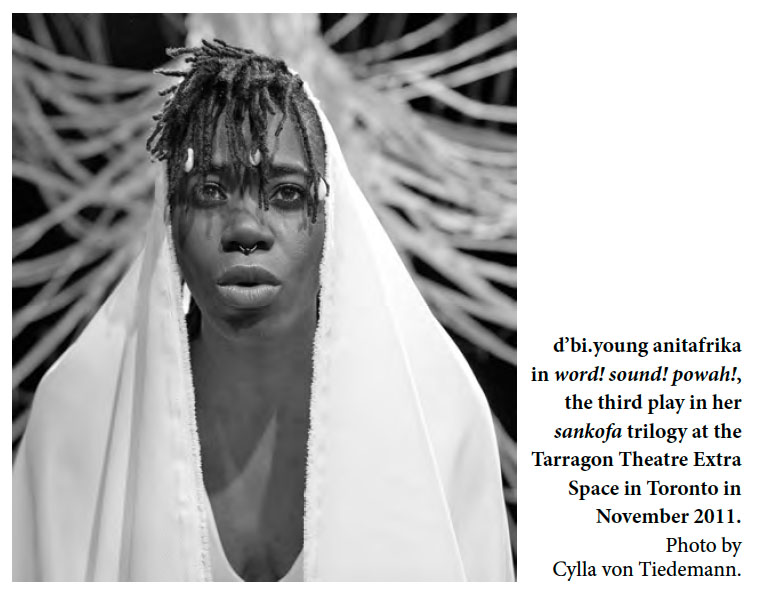

23 Biomyth monodrama and the sorplusi method are further articulated in her “wombanifesto” on “art for social transformation” posted on her website, and they manifest themselves in the sankofa trilogy, originally called the three faces of mudgu sankofa and consisting of blood claat, benu, and word! sound! powah! The plays present a complex, non-linear mapping of versions/myths of young anitafrika’s own life—her growing up in the “hard core,” “ghetto” area of Whitfield town in Kingston, Jamaica and her schooling from a young age at the legendary Jamaica School of Drama (now Edna Manley College) and the exclusive Campion (aka “Champion”) College, her early engagement with the community of artists, activists, and dub poets, her mother’s departure to Canada for three years leaving her in the care of her grannie, her sexual abuse at the hands of her uncle, and finally her own coming to Canada—onto three generations of the fictional, mythologized sankofa family women in Jamaica and Canada. The sankofa women as depicted in the trilogy are descendants of the maroons, and in particular of “queen nanny,” the powerful “obeah woman” who led the slave rebellion in 1730s Jamaica and whose story is most fully told in blood claat, but recurs throughout the trilogy. The trilogy does not constitute a linear story; indeed, like its titular sankofa bird it looks both backwards and forwards; indeed, in the first versions of the trilogy the sankofa women moved backward in chronological time as they moved forward through the generations. In the first play, blood.clatt (2003-2005), set mainly in Jamaica “in the present day,” mugdo was a young girl who had her first period at the beginning of the play and was pregnant at fifteen years of age at the end (as young anitafrika’s own mother had been); in the second play, benu (2010), mugdo’s daughter, sekesu, was a 28year-old new mother in Toronto, and in the third play, word! sound! powah! (2010), mugdo’s 20-year-old granddaughter, sekesu’s daughter benu, was involved in the “poets in solidarity” movement surrounding the 1980 election in Jamaica, the bloodiest since independence in 1962, in which socialist leader Michael Manley lost to the US-backed Edward Seaga. As revised for production at Tarragon Theatre in Fall 2011 and for publication by Playwrights Canada Press, blood claat’s “present day” is 1972; benu’s title character is only twenty years old, and the play takes place in 1992; and word! sound! powah!, retaining its 1980 story line, is simultanously projected forward to be also taking place at a future date in 2012.30

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 324 Each play of the trilogy is framed within different elements of ancient “folklore, myth, and magic,” much of it Yoruban, almost all of it womanist, and each play is grounded in a different element. Thus blood.claat (water, blood) opens stunningly when young anitafrika as the storyteller enters naked from the waist up and trailing a blood-red train—a “river of blood”—and offers a “libashun” to elogua to clear the path, and to her ancestors, for “gratitude, guidance, and protection.” She makes an offering to “yemosha [blood], mawa mother of all,” and, removing her headdress, asks the goddess ochun for “permission and her blessing for life birth” (19) and the goddess oya, for “safe passage” (20). Elsewhere, the play’s negative blood energy is wielded by the Yoruba warrior orisha ogun, who “governs metal works [and] misdirects blood fire energy” (18), and whose story is told by queen nanny, who then proceeds to tell her own story of the maroon resistance. In benu (air), the mythical and magical are represented through the benu bird, a predecessor of the phoenix and the bird of life and death in ancient Egypt, who is threaded throughout the play as “bird-womban,” with “the beak of a cock, the face of a swallow, the neck of a snake, the hindquarters of a stag, the tail of a fish, the breast of a goose…. and wings covered in white eagle feathers” (21). This bird-womban “sits atop her tree/ nesting an egg of myrrh that contains her mother’s ashes” (8) at the play’s outset, and her flight to the sun creates the world—her “children, children” (45)— by the end:

25 Part of the magic of word! sound! powah! (earth), the most overtly social, political, and historical of the plays in the trilogy, is the poetry itself, as performed by the characters, including the wordless performance of the “physical,” or “action poet,” “stamma.” But the play also incorporates opening and closing invocations of spirits and ancestors as a way of “opening up dem eyes. dem third eye. de one that lead to your soul” (36), and includes a witty and compelling creation myth about the beginnings of race. And the play is very much about beginnings. young anitafrika has said of blood.claat, but it applies to the whole trilogy, that “a lot of the mythology that comes up in the play is about envisioning new possibilities, new endings—which are also new beginnings” (qtd. in Varty). And the final stage direction in word! sound! powah!, the final play in the trilogy, is not “The End,” but “Beginning.”

26 The differences in form and content among the trilogy’s three parts demonstrate the flexibility of a form that is nevertheless deeply steeped in Afro-Jamaican cultural politics and practices. Formally, blood.claat is in part a coming-of age dub play reclaiming the curse word that is its title31 and celebrating women’s power to give life; benu is a social drama exposing the injustices perpetrated on single mothers by the Canadian medical, social, and judicial systems; and word! sound! powah! has its dub roots in Jamaican agit-prop as it mythologizes the story of young’s own mother and her activist friends in the Jamaica of the 1980s. The effectiveness of all three shows is their embodiment in a charismatic and chameleon-like dub writer-performer deeply steeped in the histories and specificities of a diasporic culture, including that of contemporary Toronto.

27 young anitafrika’s work is at once more transgressive, more political, more personal, more explicitly spiritual, and more expansively queer than that of either Spencer or mandiela, but like mandiela’s it is deeply invested in poetic language, specifically the poetry of nation language, and it is deeply “womban-centered.” And it clearly emerges from the same developing tradition. “dub theatre” and “biomyth monodrama,” as created by mandiela and young anitafrika out of an evolving, womanist Afro-Caribbean tradition in Toronto, go beyond postcolonial resistance with its tendency to reify the dominant as dominant (and therefore to-be-resisted). They expand and extend the revolutionary (and celebratory) politics and principles of dub poetry as it emerged from reggae and rasta into expansive feminist and queer realms not imagined by its inventors. These women, their predecessors, their collaborators, and their contemporaries have constituted a Toronto within the city that functions for them as a transformative space operating at the intersection of nations, sexualities, and performance forms to queer traditional theatrical hierarchies, together with the largely masculinist ethos of much Caribbean performance and the narrow chronopolitics of modernist colonial “development.” They have created and continue to develop entirely new, empowering, “womban-centered,” and “revolushunary” Afro-Caribbean forms that are (re)grounded in traditions of the gannies, the griots, the nation languages of the people, and movement and language that emerge from and celebrate Black women’s bodies in a transnational Canadian-Caribbean diaspora.

sweet chariot/sing low

sweet/sweet low (41)