Article

"No Good. Go Home":

Past Lives and Disrupted Homes in Catherine Bank's Three Story, Ocean View1

Catherine Banks’s Three Storey, Ocean View explores the concept of home from the perspective of a prospective buyer, Peg, and four families who had previously lived in the house listed for sale. In keeping with Henri Lefebvre’s definition of social space, the space of this home is shown to be both physically and temporally determined as the past occupants remain on stage, in the house, for the scenes of the present day, and Peg and her family respond to their movements and dialogue. Many of these former inhabitants have been disenfranchised through race, poverty, language, or disability and, for them, home is a prison as much as a shelter. Examining the house through Una Chaudhuri’s theory of geopathology reveals not only the instability of home and the ruptures between individual and community, home and the surrounding environment, but also the psychogeopathology of those who live there. In addition, both the playtext and the productions of 2000 and 2003 emphasize the vertical structure of the house, which reflects the architecture of Gaston Bachelard’s oneiric house. Banks thereby explores the effect of home not just on those living there, but also on the community and on future generations.

La pièce Three Storey, Ocean View de Catherine Banks explore le concept du chez-soi en empruntant le point de vue d’un acheteur potentiel, Peg, et de quatre familles ayant déjà habité une maison qui est à vendre. Selon la définition de l’espace social que donne Henri Lefebvre, l’espace de cette maison est défini sur les plans physique et temporel alors que les anciens habitants restent sur scène, dans la maison, pendant que se déroule l’action du temps présent, avec Peg et sa famille qui réagissent à leurs mouvements et à leurs répliques. Bon nombre des habitants passés ont été marginalisés en raison de leur race, de leur pauvreté, de leur langue ou d’une invalidité, et pour eux le chez-soi est autant une prison qu’un refuge. En prenant appui sur la théorie de la géopathologie de Una Chaudhuri pour examiner la notion du chez-soi, nous constatons non seulement l’instabilité du chez-soi et les ruptures qui s’opèrent entre l’individu et la collectivité, le chez-soi et le lieu environnant, mais aussi les psycho-géo-pathologies de ses habitants. De plus, la structure verticale de la maison que soulignent à la fois le texte de la pièce et les productions de 2000 et 2003 rappelle l’architecture de la maison onirique de Gaston Bachelard. Ainsi, Banks explore l’effet du chez-soi non seulement sur les personnes qui y habitent, mais aussi sur la communauté et sur les générations futures.

Home

1 The word “home” can refer to a house, town, region, or even a country where one was born or spent formative years, or where one currently lives; it can include the people living there, and it commonly holds connotations of comfort and safety. Home has been a prominent theme in Canadian literature ever since Catherine Parr Traill and Susannah Moodie wrote of their struggles to create homes in the Canadian wilderness, and Northrop Frye claimed that “Canadian sensibility” is caught up with the question of "Where is here?" (222), thus prompting the question of “Is here home?” or “Where is home?”. Ideas about home have particular resonance in Atlantic Canada, from whence, throughout the region’s history, young people have left to find work (Fuller 35). Often these economic exiles hope to go “back home” or “back East” when times are better, suggesting that such a return is regressive and that the region and “home” are suspended in the past. Indeed, Danielle Fuller notes that the current tourist industry often constructs Atlantic Canada, identified as “down home” by many with connections to the region, “through a filter of nostalgia and idealized as socially coherent spaces that are static in time” (32).

2 Gwendolyn Davies claims that the emphasis on home—and the construction of home as nurturing—found in Maritime literature results from these cycles of displacement and return (192-95). Danielle Fuller agrees with Davies that constructions of home in the region’s literature are predicated on a sense of community and social relationships (30). However, Fuller also notes that contemporary Atlantic women writers frequently challenge romantic ideas about the region and home as sites of comfort and protection, and show home to be a dangerous place hiding physical and emotional abuse, where women are prevented from claiming their own identity (33-34).

3 Catherine Banks is frequently identified as an Atlantic Canadian playwright, and four of her produced plays, Bitter Rose; Three Storey, Ocean View; The Summer of the Piping Plover; and Bone Cage, are set in the Maritimes, the last two naming Nova Scotia specifically.2 Home and the role of women are prominent themes in her plays and, in keeping with the writers Fuller discusses, Banks explores darker perspectives of home, the “dysfunctional families” Herb Wylie identifies as common in the literature of the region (86). All of her produced plays are set in a home and feature characters with conflicting views of this domestic space. Banks also focuses on issues important to the region and this, along with her identification as an Atlantic Canadian playwright, has the potential to mark her work as regionalist.3 Critical emphasis on the playwright’s geographic location ignores how the diversity of voices and marginalized groups found in Banks’s work resonate in geographically separated bioregions.4 Not only does her examination of communities and their surroundings engage with the prevailing concept in the Atlantic region of community as “home” (Barton 44-45), but it also lends itself to an analysis of home as a physical, social, and psychological space, rather than as a specific geographic region. Exploring Banks’s plays within the context of space, rather than geographic place, allows for greater awareness of the disparate conceptions of home in Banks’s work and provides an opportunity to critically assess her representation of the disenfranchised: women, the poor, the elderly, the uneducated, the sick, and those in unconventional relationships (Pryse 50).

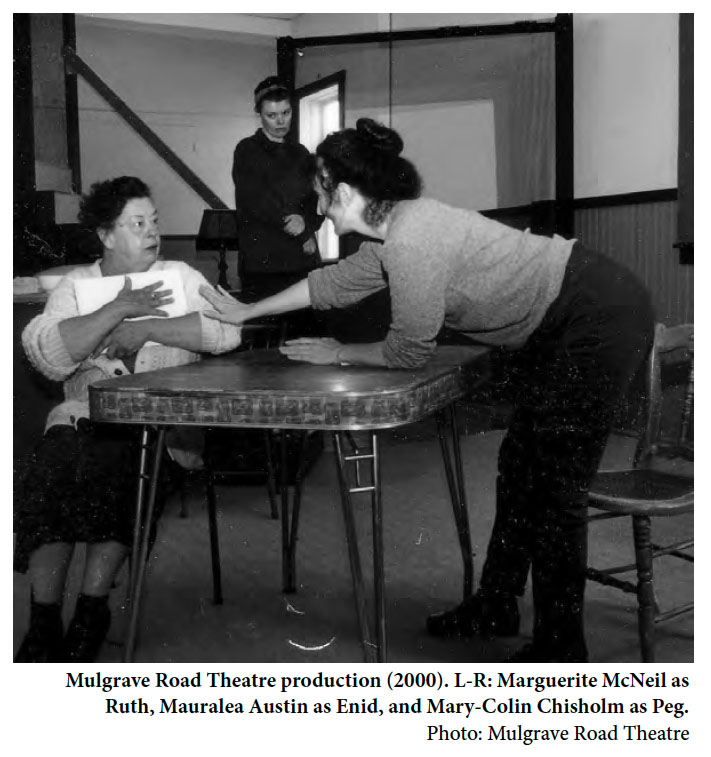

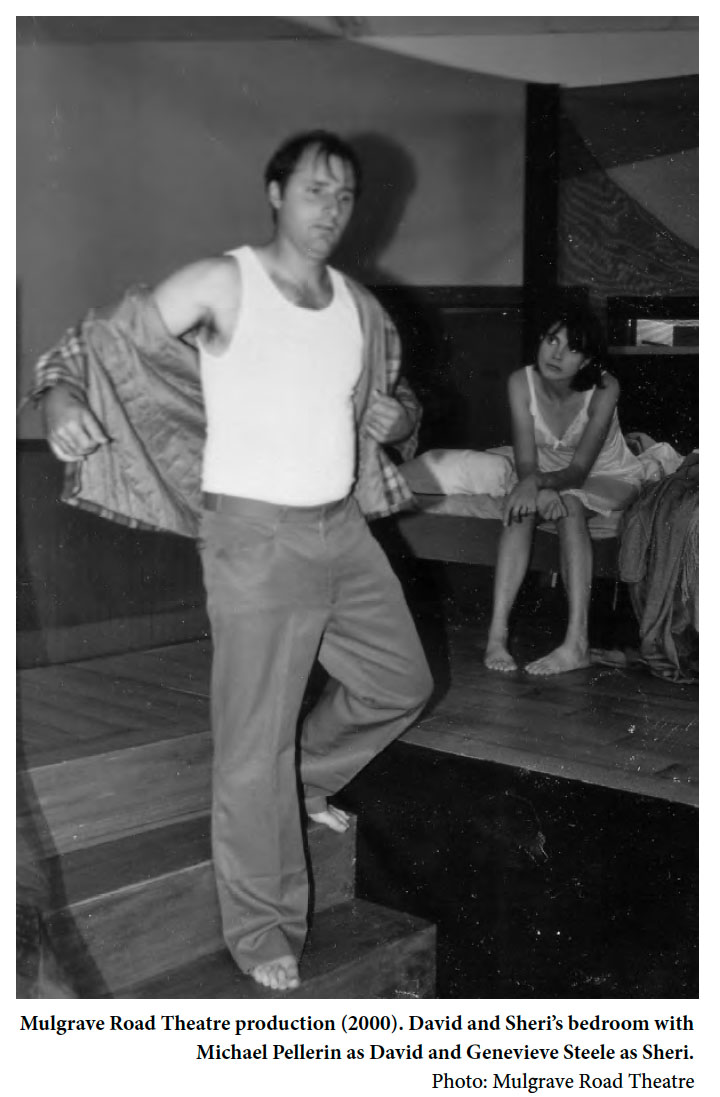

4 In Banks’s award-winning Three Storey, Ocean View, almost all of the twelve characters are marginalized.5 Set in a house for sale that is advertised as having three storeys and an ocean view, the play examines what the house means to four families, including Peg, a middle-aged divorcee who is contemplating buying the house; her mother, Ruth, who suffers from senile dementia; and Peg’s rebellious teenage daughter, Zoë. During the course of the play, former inhabitants of the house appear: the impoverished and obese Bonnie and her daughter, Cindy; the widowed singlemother, Sheri, with her new francophone husband, David, and her bitter ex-mother-in-law, Beulah; and the abused Carole, along with her disabled husband, Lud, and their young neighbour, Marsha, whom Lud has sexually abused. The play was first mounted in 2000 by Mulgrave Road Theatre as a touring production under the direction of Philip Adams, and it saw a second production in 2003 by Equity Showcase Theatre in Toronto, directed by Pamela Halstead. In both productions, a multi-level stage was dedicated almost entirely to the inside of the house, emphasizing the structure of its space. The play thereby not only explores the psychological and social space of home and its relationship to the larger community, but also, through its staging, the physical nature of that space.

Home Space

5 When thinking about home as a physical, social, and psychological space, Henri Lefebvre’s theories of space, first published in La production de l’espace in 1974, are most useful. Not only have they had significant impact on more recent theories, including Una Chaudhuri’s concept of geopathology which will be discussed later, but also they provide a way of considering space as social space. Lefebvre’s theories emphasize the process through which social space is created as compared to place as a more static marker of space. He argues that space is labelled according to the human activity that occurs there, the name or label identifying the space as a place and separating it from the surrounding unnamed (non-place) space (117-118, emphasis in original). Social space in Lefebvre’s terms may therefore be considered similar to, yet more abstract than, place as named or particularized space (Cresswell 8-10). Lefebvre begins by noting that natural space is the basis of all social space, and he distinguishes the physical, social, and mental aspects of social space using a tripartite structure, which he labels “spatial practice,” “representations of space,” and “representational space” (30, 33). Lefebvre associates spatial practice with the body, its actions, and personal awareness of inhabited space; he relates representations of space to ideas about space, conceptions usually linked to language; and representational spaces he considers to be imagined space: the “dominated—and hence passively experienced—space which the imagination seeks to change and appropriate” (38-39). He concludes by noting that the triad can be defined as “the perceived, the conceived, and the lived” (39). These divisions are helpful when thinking about theatre space, with the stage embodying spatial practice as well as being both a representation of space and a representational space (Findlay 10).

6 Differing perceptions and conceptions of the space of the house in Three Storey, Ocean View are apparent from the beginning. On first seeing it, 14-year-old Zoe proclaims it to be “[g]ross,” while her mother sees it as having “wonderful light” and “amazing potential” (2). Peg’s perception of the space is coloured, however, by her conception of it and how she envisions it as lived space. She imagines a “beautiful hardwood floor” under the “crappy linoleum” and the barn as “[a] real studio” (2). Ruth, on the other hand, regards the house as “[n]ot my house” (3), her perception introducing the idea of home and community as spaces of belonging. The house is in the village where she grew up and Peg tells her it is “[t]he house we have come home to look at” (4, emphasis in original), but Ruth does not see it as her home. For Ruth, the house does not embody the human activity associated with the social space labelled “home” and remains indistinct from the surrounding space of the village.

7 Indeed, past activities and family relations in the house demonstrate the difficulty others have had in seeing it as a home and underscore Lefebvre’s argument that space is both physically and temporally determined as an ever-shifting transition between past and present (116-118). He writes, “The past leaves its traces; time has its own script. Yet this space is always, now and formerly, a present space, given as an immediate whole, complete with its associations and connections in their actuality” (37, emphasis in original). The idea that past use of a space affects current perceptions of it also coheres with Gaston Bachelard’s views on home and his belief that the first home influences all others. Applying psychoanalytic and phenomenological approaches, Bachelard sees the house as “a privileged entity” that allows for examination of “the intimate values of inside space” (3) and always bears “the essence of the notion of home” (5).6 Connecting past and present, Bachelard writes,

8 This “house of dream-memory”—the oneiric home—is always a protective space, influenced by memories of the first home, even as it shapes those memories and the perception of that home and all future inhabited spaces (15).7 When it comes to an understanding of home, the immemorial, the imagined, and the remembered past continuously intrude on the present.

9 In Three Storey, Ocean View, present space is clearly shown to be continually influenced by the past. Owned by an American artist and her family who “stopped coming in the sixties” (24), the house then becomes home to Bonnie and her husband, Bill Hamilton, “the coloured fellar,” and their children (25); in the 1970s, Sheri lives there first with Buddy and, after he drowns, with David, “the Frenchy’s son” (26); and in the 1980s, Carol and Lud move in “after they los[e] their farm” (27). These families simultaneously appear in the house as represented on stage, along with Enid, a long-time neighbour, and with those who have come to view the property. Characters react to the voices and movements of inhabitants from another time, Ruth being particularly attune to those who have lived there. On hearing Bonnie call after her daughter, Ruth asks Enid, “Who are the people in this house?” (24). Later, she tries to warn Enid that Bonnie will kill herself by eating a lobster sandwich (116). She also repeats what Marsha says to Lud (54); and reaches out to David and Sheri in bed, seeing them as her lover Frankie and herself (43-44), while they appear to rouse at the sound of her voice (34), suggesting that the present can also affect the past.

10 The influence of the past on present space is additionally shown by characters’ views of the house as a home. Not only do Zoë and Ruth reject Peg’s conception of the house as a potential home, but the artist’s children who are selling the house also appear to have little attachment to it. For Bonnie, it is a place of entrapment (27), representing the way she is trapped in her obese body; for Sheri, the house reflects Buddy’s failure to provide “a decent place to live” (94); for Carol, it is where Lud “led [her] quite the merry dance” and where his oppressive presence is still felt (39). The house as a home is shown to be unsafe, even dangerous, especially for female characters. Given the way various characters define the concept of home and compare the house to their conception, Three Storey, Ocean View lends itself to an examination using the theories of Una Chaudhuri. Drawing on Lefebvre’s tripartite construction of space, Chaudhuri examines the idea of home in modern and contemporary drama, believing that home becomes particularly important when realism is the dominant dramatic mode. She writes, “The figure of home lends itself to one of the basic impulses of realism—the attempt to locate a space of personal experimentation: experimentation with the definition of persons, and with selfhood,” before adding, the “contradictory conditionality of the figure of home—its status as both shelter and prison, security and entrapment—is crucial to its dramatic meaning” (8).

11 Chaudhuri, like Bachelard, connects home with the architectural structure of the house; however, unlike him, she believes that the concept of home is in “uneasy contention with the figure of the house” (49, emphasis in original), noting that this troubled relationship results from “[t]he problem of place—and place as a problem”: what Chaudhuri terms “geopathology” (55). The theories of Bachelard and Chaudhuri, grounded respectively in psychoanalysis and geopathology, thereby allow an examination of Three Storey, Ocean View through the lens of psychogeopathology.8 Rod Giblett describes psychogeopathology as a psychopathology present not only at the private individual level, but in the larger public arena of community or nation-state, and resulting from “interactions with the bio- and other –ospheres” (180). He notes that psychogeopathology always accompanies geopathology and is revealed through exploration of “the underlying cultural, historical and ecological causes of psychopathology”: areas traditionally overlooked in psychoanalysis (179), but precisely the themes emphasized by Banks through the disruption between individuals, families, and the environment—domestic, communal, and natural—in Three Storey, Ocean View.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1Geopathology: divisions at home

12 The tension between “belonging and exile, home and homelessness” caused by geopathology (Chaudhuri 15) is evident in Banks’s characters. Peg is thinking of buying the house on the bay because she erroneously believes that her mother wants to return to the village where she grew up. Peg cannot take Ruth to her original “home place” (12) as it has already been sold,9 but on arrival at the house for sale, she tells her mother, “We are home. [...] This is the village where you grew up. This is HOME” (5, emphasis in original). Ruth, though, considers the house “No good” (5), whereas Zoë is adamant that she is “not living here. I’m not” (8). Zoë, apparently more in tune with Ruth’s feelings than Peg, insists that she knows her grandmother “doesn’t want to be here” (33), and it becomes evident that Ruth does not have happy memories of home. While unable to agree on the house as a home, the three women are all homeless in a way. Zoë feels homeless as she refuses to live in the house Peg wants or with her father who now lives with another woman and her daughter. She insists that she can live with her friends, though Peg says what she really wants is her mother “back home and everything [...] the way it was” (10). Ruth is also homeless as Peg has removed her from the institution—the home—where she was living because she cannot afford the fees, while Peg sees herself as having “a mother to care for, a daughter to bring up and no home” (10). Despite the attitudes of her mother and daughter and the poor condition of the house, Peg persists on seeing it as a home, claiming, “It has everything, everything, we want doesn’t it?” (3). Homeless, these women cannot agree on what constitutes a home even as they seek one.

13 The women recognize that home is not always a safe place, however. Peg presumes she is bringing Ruth back “to the place she was happy” (40), a belief founded on lies her mother has told about her childhood. Peg thinks that her maternal grandmother was “a quiet woman” who sent money for Christmas (45), until Enid reveals that Ruth “didn’t have the easiest time growing up. [...] Her father drank, that made it hard. / Her mother wasn’t easy—she had this voice on to her” (33). In keeping with psychogeopathology, Enid directly connects the abuse in Ruth’s home with the appearance of the house, saying, “It wasn’t a pretty place back then was it? Outside or in” (104). Ruth has also lied about Peg’s infancy, telling her stories about being happily married to Frankie, Peg’s father, and his early death when, in fact, Frankie was already a married man, and Ruth’s mother threw her out of the house when she learned of the pregnancy. Ruth has also told Peg, a burgeoning artist, that Frankie drew the sketches she carries, though she did them herself. When Peg discovers this, she feels separated from her mother by “this made-up father between us” and asks, “all of your stories untold for some untrue stories that were supposed to what? Make me happy?”. Enid attempts to explain: “She told those things so you would have something to hold on to” (119). Ruth’s creation of a safe dream-home for herself and Peg is not only a response to her own unstable childhood home, but is also related to Bachelard’s concept of the oneiric home. Indeed, Peg complains that her mother’s stories have created her need “to marry into being safe. SAFE. Now I’m not married and I’ve got two lives depending on me and the one place I thought was safe was horrible for her.” She adds that if she had known the truth, “We could have shared something—a passion” (119), suggesting that Ruth’s attempt to disguise the rift between her mother and herself has created a divide between her and her daughter. The breakdown of both relationships, however, is caused by something both women have in common: “a voice” that prevents any home from being safe.

14 Peg remarks that Ruth had “this voice” (36), a voice Peg realizes she has inherited when she asks, “[D]id I ever make Zoë feel loved? No, all I have done is laid harsh words on her skin and now they are etched on her bones” (83). Not only has Peg’s experience of her mother’s voice affected her treatment of her daughter, but it has also led her to marry someone with the same “measuring up voice” (75). In addition, Peg thinks that if her mother had told her about her own artistic ability, it would have encouraged her to pursue a career in art much earlier.10 Though Peg recognizes how her mother’s stories and her own childhood experience affect the home she has created, she too fashions stories for her daughter. Peg is shocked to learn that Zoë knows intimate details of her separation (9) and admits that there were “[m]iles of bitter words” between her and her husband, “enough to collect a divorce.” She continues, “What I didn’t see was that those words travelled between us through the bodies of the kids. Even the ones we made sure they didn’t hear, even the ones we kept inside” (75). With the ruptures in her home, Peg cannot disguise her psychological turmoil and realizes that all she has shown Zoë is “self-denial and anger” (83). Peg cannot create a safe home any more than her mother could, for such safe space can only be realized in a dream house, not in the real world (Bachelard 7).

15 The friction in Ruth’s and Peg’s geopathology between home as nurturing and home as imprisoning is also present in the lives of the women who have lived in the house and “had it hard” (123). Bonnie is isolated by poverty and her unconventional marriage as a white woman to an African-Canadian. She is also trapped in the house by her obesity and bad legs. Desperately lonely, she has a dream in which her abusive father treats her kindly and feeds her lobster—to which she is, in reality, fatally allergic. Bonnie’s dream demonstrates Bachelard’s claim that dreams of the first home have even greater sway than memories (Bachelard 16-17).11 In addition, Bonnie’s fantasy and its contrast to her memories of childhood increase her desire for “one small pleasure” (81): to eat a lobster sandwich she has prepared for her husband as a birthday present. Consuming the sandwich can be seen as Bonnie’s attempt to escape from the homes in which she has been trapped. It can also be seen as her attempt to transform herself into her father’s favourite child and a woman who has the freedom to walk where she wants and to eat lobster if she chooses.

16 The concept of home as a place for self-transformation is also apparent in Sheri’s story. Like Bonnie, she has experienced abuse, spending five years in an abusive marriage before her husband, Buddy, drowns. She then meets and marries David, a “good husband” (63, 114). Nonetheless, the community is critical of this marriage as it happens soon after Buddy’s death, and David is an Acadian—an outsider. Like Bonnie, Sheri dreams about her abuser but, rather than having a pleasant fantasy, she has nightmares of Buddy drowning David. Sheri’s fear of the sea, caused not by Buddy’s death, but by seeing Lud drown a puppy, leads her to be reticent about the future David plans, which includes a house on the point. Sheri’s second marriage, though, gives her space to overcome her fear of the sea. In keeping with Chaudhuri’s claim that home can be a space for “personal experimentation” and transformation (8), Sheri now has the opportunity to redefine herself. Despite the superstition that women on a boat are bad luck, David persuades Sheri to face her fear and come out on his boat with Garyleigh by telling her, “We’ve got to teach our kids not to be scared” (63). When David’s boat returns empty, Sheri has the courage to search for him and ensure that the future he has planned happens. Focusing on her children’s need, she yells, “[Y]ou promised to be a good husband. David. What about Magi? What about Garyleigh?” (114). Leaving the house and having the courage to get in the boat therefore allows Sheri literally to move on and live in the house David builds on the point with windows facing the sea.

17 Lud, the cause of Sheri’s fear, is a menacing presence despite being confined to a wheelchair and unable to speak due to a stroke. Even after his death, Enid remarks, “sometimes when I look out my kitchen window I swear I see him still” (39). Lud had abused his wife and sexually abused his daughters and a young neighbourhood girl, Marsha. Even after his stroke, his wife is at the mercy of his physical disability, though she tells him, “That don’t scare me anymore. That don’t keep me home now” (51). Carol, like Sheri and Bonnie, has not forgotten the abuse; but rather than dream, she and Marsha take revenge on their oppressor. Marsha taunts Lud with the very things she remembers him for: orange Live Savers and games that clearly became sexual in nature. She leaves him humiliated: half naked, his hair and the front of his pants spray-painted orange. Carol gains her revenge by cutting her hair. She tells Marsha, “Told me when he married me, if I cut my hair he would leave me. Good many nights on the farm I sat in that kitchen with scissors in hand” (53). When she returns to find him on the floor, Carol leaves him there while she “slowly and deliberately slips off scarf to reveal very short hair,” and observes, “I wish Marsha was here to see it. / I wish our girls could see my hair.” At the same time, she knows her defiance is too late: “[I]t don’t change the past,” she says (112). Carol previously tried to save her daughters from their father by asking for help from the community. No one came to her rescue, reflecting one of the most tragic rifts between family and community. Such “ruptures and displacements in various orders of location [...] from home to nature, with [...] neighborhood, hometown, community and country ranged in between” are symptomatic of geopathology (Chaudhuri 55), and in Banks’s plays, they frequently destabilize a sense of home.12 The specific rift between Carol and the community results from the cultural psychogeopathology that viewed men as masters of their environments: spouses, children, livestock, and land were property owned by the male head of the household. Lud, though, is a poor master: he fails to nurture the natural environment as a farmer, he violates and terrorizes the community, and he isolates and tortures his family.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 218 The geopathological division between individual, family, community, and the natural world apparent in Three Storey, Ocean View is most fully represented by Enid, the only character who moves through all four time periods and who acts as the voice of the community. She is the quintessential nosy neighbour. She sees and knows everything but provides no help. She sells eggs to Bonnie, but refuses to stay and chat even though she knows her neighbour is desperately lonely, offering the unhelpful adage, “We all have hard days Bonnie” (81). Enid refuses to take Carol’s daughters, insisting that the children belong to Lud. She asks, “How could I do that? Take a man’s children?” (105). When Carol later tells Enid that her help “might have made a difference,” she is still defensive and replies, “I wasn’t the only one you asked” (97), identifying herself with the rest of the community that ignored Lud’s abuse. When Sheri goes to search for David, Enid again ignores her neighbour’s wishes, and takes Garyleigh to his paternal grandmother, Beulah, despite Sheri’s insistence that she not do so.13 In each case, Enid, as part of the community, refuses to help these abused and isolated women. Enid also confesses that she could have done more to help Ruth, for she makes no attempt to help Frankie when he returns looking for Ruth, admitting, “He would have gone to Toronto if Ruthie’s mother or I had told him where she was” (118).

19 Enid comes to regret her failure to help her friend and neighbours, however. She tells Ruth, “I wish I’d done things different. [...] I’d do it different now” (123), and it is possible that Enid has already tried to remediate her wrongs. For someone who “keep[s her] eye on” the house (31) and knows everything going on there, it is remarkable that she does not see Lud fall in the ditch, and she evades Peg’s question of whether anyone saw him by noting that he was unable to speak because of his stroke. She is good to her word of “do[ing] it different now” when she realizes that Peg needs help to pursue her art, create a home for Zoë, and care for her mother. Noting that she has “been lonesome since Jack died” (128), Enid asks Ruth to stay with her.14 Disengaged from her neighbours’ problems, Enid’s life has been sterile, limited to “crying over a dead cat” (123), but through Ruth she has an opportunity to reconnect with people in her community. Like Carol, Enid cannot change the past, but by caring for Ruth she can provide Peg and Zoë an opportunity to make a future home for themselves in Toronto.

Postgeopathology: no going home

20 Not only do characters in Banks’s play experience the psychogeopathology associated with the instability of home and the division between home and community, but they also have “multiple experiences of place,” a characteristic of “postgeopathology” (Chaudhuri 15). For example, while Bonnie is afraid to leave the house, she feels trapped within it; Sheri sees it as a “dump” (94) when married to Buddy, but when there with David, she has the courage to seize the future she wants; and Carol, once “scare[d]” and “ke[pt] home” (51) by Lud, gains her revenge while there. In addition, Peg, Zoë, Enid, and Ruth offer multiple experiences of the house. Once “the house of the village” (31), Zoë immediately condemns it and, even as Peg sees its potential, she cannot make it the dream home she wants for her mother and daughter. Aware of her neighbours’ problems, yet believing they were “never none of our affair” (106), Enid regards the house as a home occupied by others, one to which she holds the key but that she can only visit and look into. For Ruth, the past inhabitants still live in the house. She is even more aware than Enid of the events that have taken place there as she experiences them as the present, not the past. For her, the house remains someone else’s home, not hers (12). The multiple perspectives of the house are further emphasized by the different times of the day and year that each story takes place: Peg, Ruth, and Zoë arrive mid-afternoon in spring suggesting “hope and renewal”; Bonnie’s story begins early on a morning in late fall, “a time when hope seems many long months away”; Sheri and David appear around midnight at the height of summer “when no one really expects a fisherman to drown”; and the audience meets Carol around noon in “the raw days of February— bleak” (Banks, “Re: 3SoV”).

21 Chaudhuri notes that postgeopathological works, with their multiple perspectives on place, emphasize homecoming rather than home leaving, and reveal the difficulty of making such a return (92). Indeed, despite the characters’ various opinions of the three-storey house as a home, Banks’s play demonstrates the impossibility of returning home.15 Peg believes that her mother’s request “to go to the water, the ocean” (70) indicates her desire to return home when it actually reflects Ruth’s wish to drown herself. What she discovers is the impossibility of bringing her mother home not only because the house for sale is not the “home place,” but also because her mother’s childhood home never existed as Peg imagined it to be. When Ruth rejects the house for sale as a home, and Peg realizes that her mother did not want to return to her home but to where the water was deep enough to drown, it is evident that no one can simply turn the clock back. Neither the community nor the landscape is the same. The fish have gone, and fishing is no longer the main occupation; farms have failed, and not even the beach looks like it did. Zoë also learns that she cannot return to a united family with her mother at home, while Peg has to learn not to treat Zoë like a small child. Instead, they come to a compromise, Peg agreeing to live in Toronto and Zoë content with sleeping on a pull-out couch—a return to home as well as a new home for the two of them.

Staging home space

22 Even as the house of Three Storey, Ocean View reveals ruptures at all levels between the individual and the natural world, and even as it reveals the psychogeopathology of those who live there, it also reflects the vertical structure of Bachelard’s oneiric house. Bachelard describes this “dream-memory” house as having three or four floors, with the middle floors representing everyday life and community, the attic holding pleasant memories and dreams, and the basement guarding painful memories rejected from consciousness (18-25).16 The vertical structure of the house in Banks’s play was fully staged in both the Mulgrave Road Theatre and Equity Showcase Theatre productions. In each, there was a three- or four-level set, complete “[W]ith the widow’s walk reaching into the gods” (Adams).17 As in the oneiric house, the main floor is the space of greatest interaction and conflict, a space dominated by Lud’s oppressive and Bonnie’s tragic presence; the second floor is a space of comfort and intimacy with David and Sheri’s bedroom there, a room that “has a nice feel” according to Peg (44); while the widow’s walk is a space of contemplation and seeking, a place where Zoë goes to be alone, and where Ruth and Peg wait when Zoë is missing. The floors of the house also reflect the movement of time: the main floor holding the tragic past and uncomfortable present, the second floor the comic present and hopeful future, and the widow’s walk looking only toward the future.18

23 The productions of Banks’s play also reflected Bachelard’s claim that “space contains compressed time” and that we “want [...] time to ‘suspend’ its flight” (8). Not only apparent in the interconnected narratives of the play text, the suspension of time can also be emphasized through staging. In both productions, each group of characters had their own space: what Philip Adams, director of the Mulgrave Road production, describes as “their own home inside the home house” (emphasis in original). However, these areas were open to each other, Adams believing that “all the stories told from within and about the house were one and the same, they were all buried in the walls, in the floorboards, under the beds, and, as such, didn’t disappear with the residents’ deaths or leave-taking.” While Bachelard insists that the memories and dreams of our first house/home influence our interpretation of all other spaces, in Banks’s play it is the lives, dreams, and memories of past inhabitants that influence those in the future.19

24 In keeping with this idea of the influence of the past, Adams had all the present-day characters respond in some way to those of the past. Halstead, on the other hand, had only Ruth respond to them. Certainly, Ruth is the character in the text who is most responsive to previous residents, her dementia reducing her understanding of the present but perhaps creating a stronger connection to the past. In both productions, she also moved freely between the spaces occupied by characters of the past. Halstead writes, “Ruth is key to making Three Storey work on stage. The transitions should be as seamless as possible from present to past and back. It is Ruth’s attention and where she is engaged that drives our focus.” Adams, conversely, had all the actors remain on stage for the duration of the play as a reminder of the strong influ ence of the past lives, the characters moving quietly about until their scene, when the lights followed them. Lud, as the most oppressive character in the play, was kept in full view throughout. Adams explains his rationale for this, “I found most people [...] want to disappear these tough stories, bury the truths about their relatives/themselves. I worked against this trend.”

25 In drawing attention to the “tough stories” of the Atlantic region, Adams stays true to the “truth-telling” he sees in Banks’s work. He considers it “the bedrock upon which she stands her characters, it predicts how they will react, how they respond, and how they choose to live out their lives: the truth will out.” Through her truth telling in Three Storey, Ocean View, Banks explores the multiple perspectives of home as seen by the marginalized, mostly women: the ostracized, lonely, sick, impoverished, abused and those unable to prevent abuse. In doing so, she examines the circumstances that lead to the marginalization of such individuals and the conditions related to rifts in family, community, and natural environment. Such ruptures are symptomatic of geopathology as described by Chaudhuri and, as an examination of Banks’s play reveals, are accompanied by an inherent instability of home: a need to leave it and an inability to return. Such experiences of home are often related to characters’ childhoods and thereby reflect Bachelard’s argument that even as the first home affects and is affected by the oneiric home, it also has an impact on all future homes. Banks explores the impact of the experience of home not just on the individuals who live in them, but on their communities and future generations. There can be no return to an idyllic, bucolic state. Characters can never fully rectify past wrongs. They can only offer uncertain hope for the future. However, such hope can transform the bleakest lives.