Forum

Coherent Confusion and Intentional Accidents:

bluemouth inc.'s Dance Marathon

1 To play ‘Exquisite Corpse,’ one person writes down a question on a piece of paper. That person tells the other people playing to write down an answer to the type of question she is asking, without telling them what the specific question is. For example, “Write down an answer to a why question.” Then she reads aloud her question. Everyone else reads his or her answer. For instance:

2 In Dance Marathon, a drum solo sounds like a (good) drum solo. However, in the pervasive intermediality of Dance Marathon a drum solo also speaks, a drum solo does:

Don’t watch what their body is doing.

Don’t look at the way they’re moving.

What you should be focusing on is the space that is sculpted by their body.

I’m serious.

Look at it.

You should really see a person as a sculpture.

No, you should see a person as a sculptor.

As someone who sculpts space with their body.

What you need to do is imagine the air is clay. Everything is clay.

And the person you’re watching is a sculpting instrument.

Like they’re a sculpting tool.

Like they’re a cutting knife.

So.

You can tell a lot about someone by the space they carve in space.

I’m serious.

It’s like information they’re not even aware of.7

Projected at dizzying speed on the huge jumbotron that claims one end of the dance hall, electronically regulated by the beat of his bass drum, composer Richard Windeyer’s reflections on movement in space sound an anthem and unravel a code (of conduct), warning participants to avoid the obvious, the concrete, the quotidian. Attend, rather, to the peripheral, the virtual, the unexpected. Mistrust your perceptual competence in order to exceed it.

3 bluemouth inc. is a site-specific intermedial performance troupe made up of Stephen O’Connell, Sabrina Reeves, Lucy Simic, Ciara Adams, and Windeyer. It holds split residence in New York City, Toronto, and Montreal and is an intersection of dance, performance art, visual media, electronic music, lyric poetry, and psychological realism. Aggressively collaborative and interdisciplinary in its approach, its material consistently brings both traditional theatrical and event-based performative conventions into problematic and unpredictable collision. One of the defining aspects of this juxtaposition of contradictory orientations—of, on the one hand, establishing a theatrical relationship or ‘contract’ and, on the other, of instigating performative interaction—is the inevitability of confounded expectations. Via intentional and defining miscommunication and misreading, which extends beyond form and content into issues of deep aesthetic and ideological significance, bluemouth invites, ushers, and coerces an audience into an immediate experience of environmental intermediality.

4 During the 1920s and continuing into the 1940s, dance marathons were magnets for popular attention throughout North America.8 They could last for hours, days, weeks, or months, during which participants regularly rested for ten or fifteen minutes per hour but otherwise had to keep moving. Hugely popular and morally suspect, they pitted participants who walked in off the street against seasoned competitors and professional entertainers, effectively blurring these distinctions. As Carol Martin notes, “A coterie of professional contestants developed in response to the demand for showmanship and special entertainments. Novices with ambitions to be celebrities—or at least professional entertainers—and a small contingent who thought of themselves as endurance athletes went from show to show” (51).

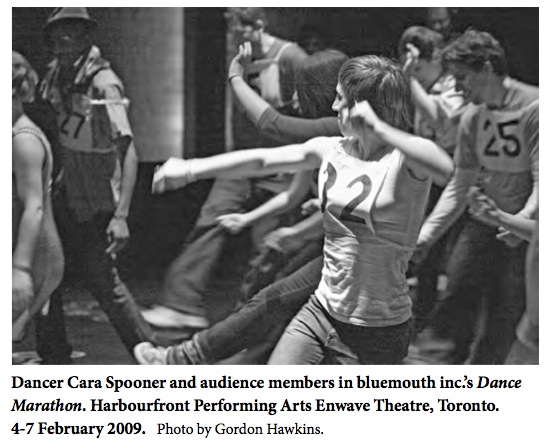

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 15 Contestants were fed and provided with accommodation during the worst of the financial Depression, and were made dubious offers of “fame and fortune”; they were also duped, abused physically and mentally, and often deprived of the most basic dignity. Almost continuously exposed, the contestants’ lives were turned into spectacle, their most incidental and personal activities and choices transformed into a life-and-death match of Trivial Pursuit. In the process, the lines between entertainment and sport, theatre and event, were hopelessly muddied. As such, multiple sets of conventions operated simultaneously, jarring and butting up against one another, complicating, overlapping, and contradicting one another. Meaning was not so much negotiated as disputed, a prize to be won through force, guarded fiercely, and possessed only ever temporarily. Dance marathons helped lay the groundwork for North America’s enduring obsession with mediated “reality,” rendering irretrievable any clear separation between the private and the public domains.

We prayed to god,

To buy more time and celebrate in sacred shrines,

Our lives.

6 Participants are given a number to wear when they arrive and are asked to fill out a form with questions about their general health and information about rules, water, rest periods, and pee breaks.

And European monarchs flung

their partners round the banquet hall with ease.

Each number corresponds to a set of ‘dance lesson-style’ feet taped to the floor somewhere in the dance hall. Each participant must ‘find her feet’ before the performance can begin. Everyone is paired—closely—with someone other than the person they came with. It takes time to find your feet.

Used country-dance to get them close,

handed down through centuries

this folkdance is still popular today.

Rule #1: Never stop moving your feet.

A war had made things all seem strange,

Folks sought opportunities for fun,

Any excuse to put down that old gun!

The night gets under way amid much laughter, nervous small talk, freeform movement, and some cautious groping. Gradually, more rules are introduced, then adopted, then changed, then increased, then policed, then broken. There are trivia quizzes, athletic competitions, celebrity guests, stray moments of theatre, nightclub songs, full-floor dance numbers, and much, much dancing.

Oh it proved, we could move, just by,

Kicking our legs out.

7 What could be more private than dancing? Two people, insulated from the world by movement and sound and the level of attention only possible when locked in a physical embrace. What could be more public than dancing? A room full of people, executing shared and mutually approved choreography— gestures, rhythms, pacing, spatial organization—and, in the process, validating the concept of culture. With the unblinking gaze of a network of stationary and hand-held video cameras, its participants projected relentlessly and unpredictably (yet never arbitrarily) throughout the performance space, Dance Marathon uses this complicated series of paradoxes to explore the possibilities of relational performance by both celebrating and demystifying the possibility of intimacy within an intermedial communal event.

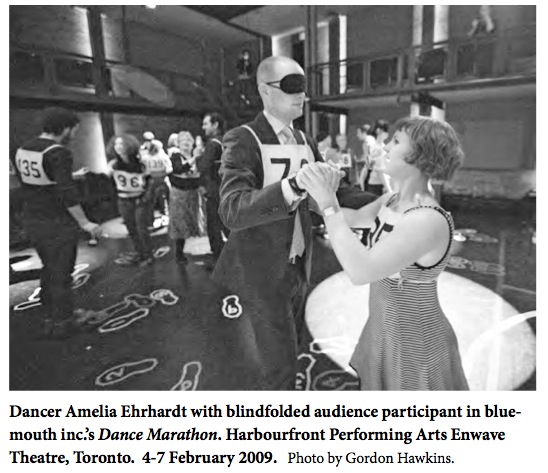

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 Psychologist Karen J. Prager makes a distinction between intimate relationships and intimate interactions. Intimate interactions refer to behavior that exists within a clearly designated space-and-time framework, whereas intimate relationships exist in a much broader, more abstract space-and-time framework and continue in the absence of any observable behavior between partners. Unlike intimate relationships, intimate interactions are highly influenced by the conditions of the immediate context. And while only a few of the interactions in an intimate relationship are actually intimate, intimate disclosures may occur in interactions between strangers precisely “because of the unlikeli-hood of a further relationship and the attendant opportunities for betrayal” (19, emphasis in original).

9 In my experience of bluemouth inc.’s performances, the uncertainty and ambiguity that characterize the company’s commingling of theatricality and performative action consistently risks, commits, and then recuperates precisely this deeply intimate “betrayal” of expectations. This emphasis on intimate interaction that is at once intense and volatile, while also rehearsed and adjudicated, thus takes the form of a particularly charged variety of intermedial ‘misfiring’—one that ignites at sites of pronounced vulnerability and self-exposure, both propelling and perpetually disrupting the possibility for stable performer-audience interaction.

10 Dance Marathon invites and enforces an endless succession of involuntary intimate interactions throughout its four hours. As noted, participants who arrive in pairs are intentionally separated from the outset, and many of the sequences involve extended dance sessions with constantly changing partners. At the same time, however, every possible corner in the theatre is under video surveil-lance, vulnerable at any time to being suddenly projected on one of the multiple video screens throughout the space. In a related gesture, the general openness that is fostered through the many forms of exchange between participants is regularly complicated by the demand to compete, individually and in pairs, in foot-race derbies, in morality quizzes, in dancing contests. “Survival” on the dance floor is thus equally dependent on two opposing dynamics among the participants: mutual support and competitive individualism.

11 Similarly, the performance begins with no clear indication of who—beyond the Master of Ceremonies,9 the band, and the Referee10 —is an audience member and who is an ‘embedded’ performer. Over the course of the evening recognizable ‘characters’ begin to emerge: Little Stevie O’Connell (O’Connell); Lady Jane (Adams); Ramona Snjezana Knezevic (Simic). But their ‘stories’— often subtle yet at times grandly spectacular—are indistinct, piecemeal, and subject to contradiction. The first betrayal—that which separates performers from the rest of the audience through the assumption of apparently stable, theatrical character traits—is thus followed by another, as the same ‘characters’ fail to cohere or adhere to the expectations they have generated.

12 In addition, the professional dancers that mingle throughout the other unsuspecting participants reveal themselves only slowly at first—through a too-graceful move, or a sudden unusual competence that appears but then dissolves back into the mix, leaving those who witnessed it unsettled and unsure of what they have experienced. Eventually, there is a “Blindfold Dance,” during which the professional dancers place blindfolds on their partners and do an elaborate piece of group choreography around them. During the first run of the performance, many of their partners did not realize what had happened and failed to recognize the dancers as ‘plants.’ By the time the floor came alive with larger scale choreography that everyone could see (particularly when streamed live throughout the hall), many audience members were deeply resistant to ‘surrendering’ the floor, even in the most strenuous and complicated of pre-established dance sequences. Participants hung on, refusing to let theatre (let alone media) claim the performance space, competing with the dancers in terms of endurance and ability. Agency and ownership of the space, as in the original dance marathons, were not so much negotiated as disputed, prizes to be won through force, guarded fiercely, and possessed only ever temporarily.

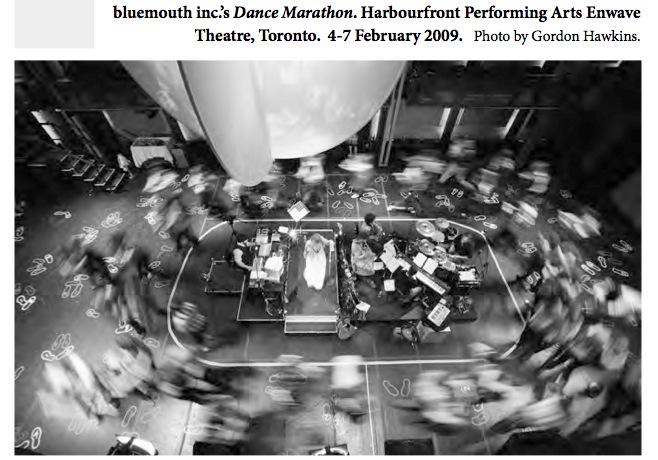

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 313 There is one almost still moment in Dance Marathon. Little Stevie O’Connell is invited up to the microphone to read a poem, entitled “Yellow Bike,” for the audience that has been dancing for several hours.

Wrong shoes

Wrong life

Wrong father

Married to the wrong wife

Everyone shuffles softly as Stevie gets sentimental. The bustling, contrary performance settles back on its haunches, almost but not quite still. It is a lovely poem. It is lovely theatre. Then

The Referee. The figure tasked with keeping everyone moving. Refusing to concede, to accommodate (theatre?). Stevie replies, timidly,

The Ref is unsympathetic (unempathetic?). Just doing his job.

What are we waiting for? Against our better judgment, but irresistibly, Stevie speaks for us.

Results from a grant that I wrote so long ago that I don’t even remember what I said.

My grey-faced and bald mother gently receiving her second round of chemo drip at Columbia Presbyterian. Lucy to come home from work at 6 am, uncertain if she is having an affair or has been mugged on her bike ride home from NDG to Old Montreal. Secretly hoping the latter because the former would be too difficult to handle.

The pain in my head to stop throbbing.

The light to cease shining.

The swelling of my brain to subside.

An entire weekend for the results of my blood test to determine if the lump on my groin that has been growing over the past six months is benign or malignant.

My uncle to die because he no longer recognizes my aunt and the gargling sounds of his collapsed lungs make me want to cry.

My mother to return from her adulterous affair in Europe.

The return of the gentle man who emotionally revealed himself in my mother’s absence.

Third grade report card.

The overdue visa bill.

The fucking idiot on table 23 to sign his god damn credit card at 4 in the morning so I can process his 10% tip and do my cash out and go home.

You to stop talking so I can tell what I think.

Song to end.

Document to download.

Interests rates to go down.

Exchange rates to go up.

A train at 2 am.

My student loan cheque to arrive in the mail after being sent back because the zip code was incorrect.

My luck to change.

By this point in every performance of Dance Marathon that I have attended the dance hall was hushed, barely moving. There was not a dry eye in the house. The moment is crucial to Dance Marathon. It is the still eye in the storm—and it is Dance Marathon’s other. It is what the entire evening waits for—and then resists, defiantly. And it is perfectly wrong. There was a palpable sense of the whole event stepping on its own intermedial toes, catching itself gazing at its own awkward reflection in the mirror of representation, both play and ‘a play,’ entranced, before it shook free its many, contentious limbs and began the uneven lurch back to movement, to contention, to celebration, to the animating betrayals of performance. Because, finally, the participants were not only waiting.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4