Forum

The Casting and Makeup of Drama, Theatre, and Performance Studies in Canada:

A Report on the Discipline by the Numbers (and Letters)

Abstract

Are we poised at the outset of a faculty hiring crisis in Drama, Theatre, and Performance (DTP) studies at Canadian universities? The question has been raised before, and perhaps at no time more frequently than in recent years as more students are entering graduate school and completing their degrees following the worst financial downturn in seventy-five years. Reactions range from malaise ("It was bad twenty years ago too") or comparativism ("It’s bad in other disciplines, and in other countries too") to economic determinism ("As the stock market goes, so too university hiring; things will get better") and even panic ("After years of sending out job applications I’d be a fool to stay on the job market any longer"). But what do we really know about DTP graduation and hiring rates in this country? This quantitative report updates and deepens past attempts to analyze perceptions about DTP education by offering aggregated "personnel flow" and "student flow" statistics generated from current Canadian university tenure-stream DTP faculty and graduate student population data. Faculty data were gathered primarily from university DTP and English department websites, and graduate student data were gathered primarily from records held at the University of Toronto’s Graduate Centre for Study of Drama, the largest single source of DTP faculty in Canada.

Résumé

Les universités canadiennes sont-elles sur le point de connaître une situation de crise dans l’embauche de professeurs dans le secteur théâtre, dramaturgie et performance? La question n’est pas nouvelle, mais elle se fait plus pressante ces dernières années alors que de plus en plus d’étudiants entament et terminent des études supérieures au moment même où se produit le plus important ralentissement économique en soixante-quinze ans. Les réactions varient, passant du malaise (« C’était difficile aussi il y a vingt ans ») ou du comparatisme (« C’est la même chose dans d’autres disciplines et ailleurs au monde »), au déterminisme économique (« Les embauches en milieu universitaire varient selon le marché boursier ; la situation va s’améliorer ») et à la panique (« Il faut être fou pour choisir de rester sur le marché du travail après avoir cherché un poste pendant plusieurs années »). Mais que savons-nous au juste du nombre de diplômés et du taux d’embauche au Canada dans le secteur théâtre, dramaturgie et performance? Ce rapport quantitatif propose une mise à jour du dossier et approfondit d’autres tentatives d’analyser nos perceptions de l’éducation dans ce secteur en offrant des statistiques globales sur le « flux » d’employés et d’étudiants obtenues en consultant les données actuelles sur les professeurs universitaires occupant un poste menant à la permanence et sur les étudiants de cycles supérieurs dans ce secteur. Les données sur le corps professoral sont tirées principalement des sites web de départements universitaires de théâtre et d’anglais, tandis que les données sur les étudiants des cycles supérieurs sont tirées essentiellement des dossiers du Graduate Centre for the Study of Drama à l’Université de Toronto.

Purpose and Precedents

1 Just over a dozen years ago in these pages, Jennifer Harvie, Erin Hurley, Carrie Loffree, and Shelley Scott wrote four pieces, collected as "Forum: Graduating Professionals," that considered the state of Drama, Theatre, and Performance (DTP) studies from the Janus-headed perspective of the job market. As then editor Deborah Cottreau introduced them, they were "four young professionals examin[ing] the state of the teaching profession such as it stands today" (115). They reflected, respectively, on the troubling ratio between graduating students and available jobs, the problematic dialectic of "intellectual stimulus" versus "marketability," the growing expectations for interdisciplinarity, and emerging graduate funding and training "areas of concern" at the University of Toronto’s Graduate Centre for Study of Drama from where, as Scott noted anecdotally, between 1987 and 1997 about 1 in every 5 graduates found tenure-stream employment. Together, these pieces addressed disciplinary issues of pressing concern for those who were entering the job market at the time, as well as for those already employed in the discipline. The intention of the present report is to update the personnel-related elements of these forum pieces by gathering and analyzing relevant quantitative data.

2 Today, concern—much of it anecdotal—circulates with regard to graduate education and tenure-stream hiring across the humanities. Is there a job market—academic or otherwise—to support actual (or potential) graduate enrolment? I brought the present case for concern to the attention of the Executive of the Canadian Association for Theatre Research (CATR) at our annual conference at Congress 2009. I had observed that during the 2008-09 academic year, of approximately half-a-dozen advertised fulltime DTP positions in the country just one had gone to a graduate of a Canadian DTP doctoral program. I asked whether CATR might view this as a disciplinary phenomenon that deserved further attention.1 After all, there could be "serious ethical questions" (Groarke and Fenske 1), to borrow language from a related study of the discipline of Philosophy, regarding admitting, funding, and graduating an oversupply of students into a market that cannot accommodate them, especially in their own country. Could it be that the very professors who teach and mentor students for a decade or more are not able (or willing) to hire them? Could it be that the quality of the education graduates receive in Canada is not high enough to warrant tenure-stream appointments in the eyes of the very professors who train them? Or, is there a more profoundly endemic situation at play: After decades of hiring non-Canadian-schooled professors, are Canadian humanities departments now populated by foreign-educated faculty who would not deign to hire graduates schooled at universities in the country in which they themselves are employed? Furthermore, what have been the effects of interdisciplinarity on hiring in the humanities since Hurley’s forum piece? In the eyes of an English department, for example, is the Canadian Studies graduate who specializes in literature but is also trained in economics and sociology as employable as the English-studies graduate who specializes in Canadian literature? And in a similar vein, what are the prospects for DTP graduates whose chosen education is "interdisciplinary," yet subject to the discipline-specific hiring habits of more traditional departments? It is the position of this report that these broad questions, marked as they may be by nationalist rhetoric, can in fact be usefully addressed by quantitative methods that have the potential to produce actionable results.

3 Picking up where the "Graduating Professionals" pieces leave off, this report updates and deepens ongoing self-analysis of DTP studies by offering a quantitative study of current tenured and tenure-stream DTP faculty at Canadian universities, featuring aggregated results culled from available data. As graduate units may face the possibility of ramped up enrolment at a time of reduced prospects for hiring, this report will be of interest to professional associations such as CATR, as well as program chairs, graduate and undergraduate coordinators, other tenured and tenure-stream professors, scholars now on the job market, current graduate students, undergraduate students considering graduate school, funding bodies, and public policy-makers. The report addresses a range of common assumptions about hiring trends, faculty complements, and specializations taught and researched, as well as graduate "student flow." Specifically, it reports on where and in which specializations DTP faculty are employed in Canada; the highest credentials they hold; where, when, and in what discipline they obtained their credentials; the recent influence that graduates of the University of Toronto’s Drama Centre have had on DTP studies in Canada; and overall hiring trends for DTP faculty in Canada. In a sense, this report starts to bring DTP studies and its constitutive departments up to speed with other disciplines that are currently engaged in collective introspection, with the aim of long-view planning, self-definition, and self-preservation.

4 There are several other precedents to this report, three of which deserve brief mention here insomuch as they partially frame it. A decade before the Harvey, Hurley, Loffree, and Scott pieces appeared, University of Alberta Drama professor Gordon Peacock, in his entry on "Education and Training" in The Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre, referenced the Canada Council for the Arts’ "Report on the Committee of Inquiry into Theatre Training in Canada," commonly referred to as the "Black Report." Peacock stated that by the late 1960s, "almost all French- and English-speaking universities had theatre departments offering a wide range of practical and theoretical courses," though most theatre faculty had been trained in England, France, or the US (193). Between the 1960s and the 1980s, however, the number of Canadian-trained drama faculty rose from one-tenth to three-fifths of university and college teaching positions (193). By 1978, "educational theatre programs in colleges and universities [had] become the largest theatre enterprise in Canada" (191). Though he focused mainly on practical theatre training, Peacock provided some historical context for charting the growth of postsecondary DTP scholarship in this country. Underlying his narrative is the suggestion that by the 1980s, as the "largest theatre enterprise in Canada," postsecondary theatre training could outpace the theatre job market into which more and more graduates flowed.

5 A second precedent, published in the same year as the "Graduating Professionals" forum pieces, is a report jointly commissioned by the Association of Canadian College and University Teachers of English (ACCUTE) and the Canadian Association of Chairs of English (CACE). Authored by University of Toronto English professor Heather Murray and titled "Hiring, Faculty Complement, and Enrolment Patterns in Canadian English Departments, 1987-1997," the "Murray Report" grew out of concerns that "many doctoral candidates (and ACCUTE members) [had become] increasingly alarmed by rumors [sic] that most tenure-track jobs annually advertised in English in Canada were going to candidates (whether Canadian or not) who held PhD degrees from non-Canadian universities" (Holton 11). In fact, the Murray Report found that during the ten years surveyed, one-third of tenure-stream English positions had gone to candidates with non-Canadian doctorates (3% of these held non-Canadian citizenship) (Holton 11). For the 2008-09 annual update, the proportion of faculty hired with non-Canadian doctorates had risen to about half of the 26 new hires at English departments (Ty 12).

6 Third, in November 2009 a study authored by professors Louis Groarke and Wayne Fenske titled "PhD: to what end?" provided "a snapshot of the faculty complement for tenured or tenure-track positions in major Philosophy departments in Canada" (1). They found that "About 70 percent of tenured and tenure-track professors in major Canadian philosophy departments have been awarded degrees from non-Canadian (usually American or European) institutions"; at the four "most prominent" institutions—UBC, Toronto, Queen’s, and McGill—foreign sources for the doctorate made up closer to 80%; and in Western Canada, over 85% (2). Groarke and Fenske went so far as to suggest that in the context of "discussion about discrimination in university hiring [o]ne could argue that Canadian PhDs are, in the eyes of top philosophy departments, ‘educationally handicapped’" and that discriminating against Canadian graduates, if that is what is happening, "is unfair and perhaps illegal" (3). Moreover, they asserted that, on moral grounds, "[s]tudents hoping for academic distinction or high-level employment should, it seems, be dissuaded from enrolling in Canadian programs. Any other approach would be intellectually dishonest" (4). The online publication of the piece has since received more than three dozen comments debating the position or proffering anecdotal additions from a range of other disciplines (one appended comment points to the fact that many faculty job ads state that "in accordance with Canadian immigration requirements, priority will be given to Canadian citizens and permanent residents of Canada"). Even an op-ed piece in the Winnipeg Free Press shook the debate from atop the "ivory tower" by arguing that the Groarke and Fenske proposal was "bizarre" and amounted to "reheated Trudeau-era nationalism." Somewhat more constructively, the columnist suggested that the low number of tenure-stream Canadian-schooled Philosophy graduates simply reflected the low number of doctoral programs in Canada, compared to the United States (Jerema). Still, I wondered, as Groake and Fenske explicitly encouraged their readers to do, if the same circumstances may exist for other disciplines in Canada. Thus, following the Murray Report and the Groake-Fenske study, whereas English departments find half to two-thirds of their hires received the doctorate from a Canadian university, and Philosophy finds as low as one-fifth for the same, DTP has, until the present report, relied on anecdotal speculation.

7 Collectively, what these precedents suggest is that among junior and senior scholars in Canada there is measurable concern over "personnel flow" across humanities disciplines. I define "personnel flow" here as the paths scholars follow from their initial interest in pursuing graduate education in a discipline, to subsequent admission into graduate school, to graduate-degree completion, to tenure-stream appointment within the discipline. It is the interest of this report to begin to get DTP studies "caught up" with other disciplines in terms of self-knowledge and disciplinary direction.

Methodology

8 This report’s methodology arises from the discursive position that the state of a discipline within a given geopolitical area can be productively, if partially, understood through analysis of the composition of its constitutive personnel. Thus, the report follows an overtly structural approach to the otherwise fluid constellation of cultural practices that constitute the teaching, research, and practice of DTP studies. It provides both a snapshot of DTP studies at the present moment and a long view of the discipline’s dynamics over time.

9 Among all possible personnel, the report focuses on university tenure-stream faculty under the assumption that permanency of hire reflects institutional commitment to personnel, research, and teaching specializations, as well as the discipline broadly drawn.2 In order to generate data, during the month of January 2010 I conducted searches of all graduate and undergraduate English-language DTP and English departmental websites from universities that are members of the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC). At universities where no English-language DTP department or English department exists, the French-language equivalent was surveyed (e.g. Université Laval’s Département des littératures or Université de Sherbrooke’s Département des letters et communications). In total the report recorded 506 currently employed DTP faculty members in 93 departments (48 English, 34 DTP, 4 combined English and DTP, and 7 others) at 52 universities across Canada, hired as far back as 1965.3 For each faculty member her or his rank was recorded, followed by department name, university, stated DTP-related specializations, calendar year of appointment, and each degree or certification earned (with corresponding program, institution, country, and calendar year of completion). Where data from online department listings were incomplete, they were supplemented with data obtained from searches in Digital Dissertations and other reliable web resources such as personal websites and university web magazines. The report’s per capita statistics made use of recent population data available on Statistics Canada’s website. The size and breadth of these data allow for a robust aggregated picture of current DTP teaching, research, and practice among tenure-stream university professors across Canada.

10 For "student flow" findings at the University of Toronto’s Drama Centre, in May 2010 I collected data for the calendar years 1999-2009 from the Centre’s own records as well as the university’s "Repository of Student Information" (ROSI) computer system. This was accomplished with the kind aid and guidance of Drama Centre staff.4 I used dissertation defence dates to track completions (post-September defences normally result in convocation in the following calendar year). In July 2010 I gathered graduate employment data from web searches.

11 A note on selectivity: whereas this report tracked the institutional paths that faculty members have taken to their present destinations, it did not collect demographic data such as citizenship, ethnicity, sex, or age. Whereas it presents data related to emergent "boom" and "bust" years for graduation and hiring, it does not draw definitive conclusions as to the reasons for these ebbs and flows, in large part because it recognized the varied and complex local conditions that can influence hiring decisions. Whereas it sought to address employment prospects for Canadian university graduates, only once (for the Drama Centre findings) did it survey options for employment outside of universities, including private and community colleges, and non-academic employment such as government, the private sector, and professional or non-professionalized theatre. And whereas it aspired to inform, it was not interested in making moral judgments (as the Groarke and Fenske piece did for Philosophy).

12 Finally, there are two factors that may contribute to potential inaccuracies or misleading data. First, DTP faculty whose names were not listed on department websites as of January 2010 (very recent hires, for example) would not be represented here. And second, errors, omissions, embellishments, or outdated material within faculty biographies on department websites may be reflected here if they could not be corrected through the reliable web resources mentioned above. Nevertheless, given the volume of data collected and the care taken to track and enumerate these data, I am confident that this report paints a reliable portrait of faculty who are teaching, researching, and producing drama, theatre, and performance at Canadian universities today.

The Report

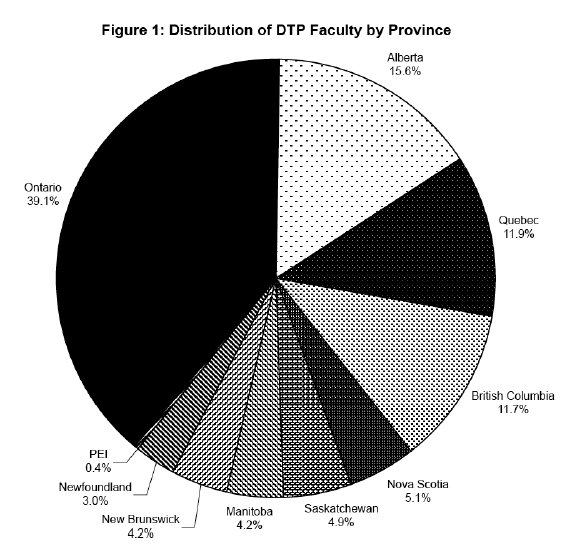

- Where are current DTP faculty employed? The report found that nearly half of all DTP faculty in Canada are appointed to DTP-specific departments, while just over one-third are appointed to English departments. The impact of inter-disciplinarity on DTP studies is evidenced by appointments to interdisciplinary departments and by cross-department appointments, which when taken together employ one-fifth of all DTP faculty. Geographically, the university-rich province of Ontario employs the most DTP faculty in the country (one-third), Alberta the second largest, followed by Quebec and British Columbia [Fig. 1]. These numbers represent a fairly even per capita employment distribution across the provinces—between 1.3 and 2.9 DTP faculty per 100,000 people—with a spike across the Atlantic provinces and a dip for Quebec (this dip may result from the fact that the report focuses primarily on English-language programs supplemented by fewer equivalent French-language programs in Quebec).

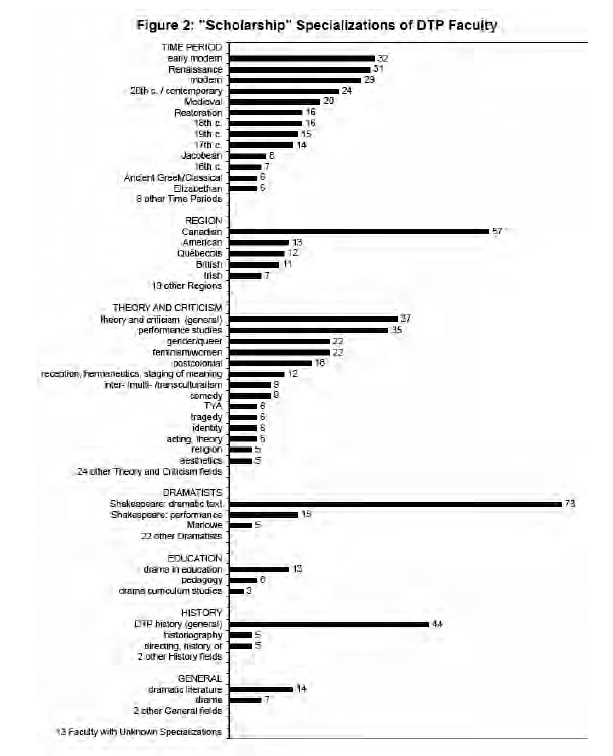

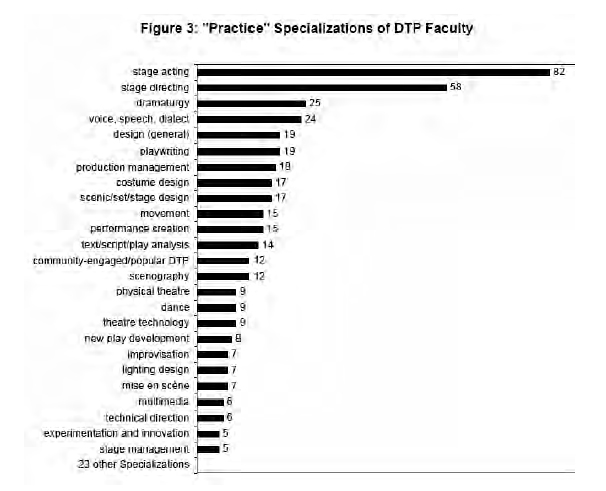

- In which scholarship and practice specializations, and in what proportion, are current DTP faculty engaged? The report recorded 141 unique DTP-related specializations among faculty clustered into several broader categories under the general headings "Scholarship" and "Practice" [Figs. 2 and 3].5 There is wide topical breadth here, with the 15 most common specializations pursued by between 16% and 4% of all current DTP faculty. It should be kept in mind that several of these specializations overlap and could be combined. For example, early modern, Renaissance, and sixteenth-century drama could be combined to rank among the most common; the same would be true if modern drama were combined with twentieth-century/contemporary drama. They are left separate here to reflect the vocabulary distribution articulated by faculty members (or their departments). The fact that most faculty list multiple specializations is no doubt symptomatic of hiring and career path conditions in most arts and humanities disciplines in which multiple specializations are sought to fill present needs. Moreover, the history of DTP is that of an emergent discipline, always already "performing" its various roots and influences in English, History, Interdisciplinary Arts, Anthropology, Sociology, and so on. It may also be attributed more specifically to recent pressures to overlap traditional periodization with a variety of methods or approaches (see Knowles vii). Habits within the discipline may encourage multiplicity as graduate education increasingly emphasizes interdisciplinary training and departments align themselves to offer an increasing number of non-traditional specializations while still serving the periodized and thematic breadth of the discipline. It is therefore important to note that faculty who specialize in one or more time periods or regions, for example, may list multiple theory and criticism specializations as well. Moreover, the very terms they use—"contemporary," "Canadian," "Shakespearean text," "acting," "drama"—may find destabilization in their own teaching, research, and practice. Indeed, the terms "scholarship" and "practice" themselves may find their most comfortable home in academe when they are brought into question, even as they are listed for the sake of discursive and biographical concision.

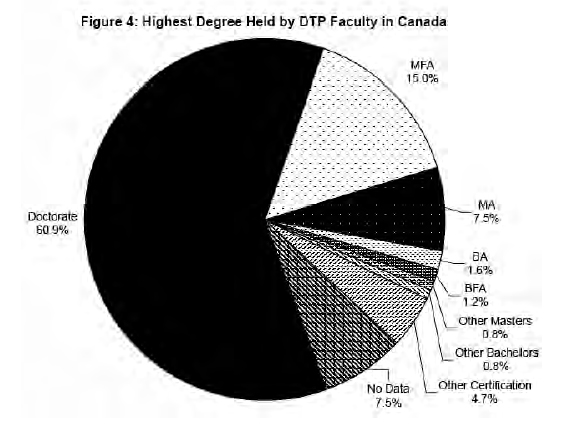

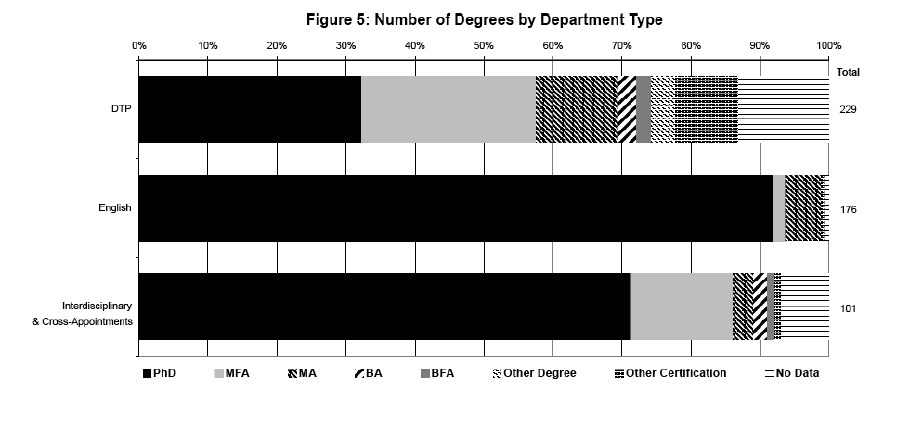

- What is the highest degree held by current DTP faculty? Could any other discipline permit more education and training paths to faculty appointment than DTP studies? While three-fifths of DTP faculty in Canada hold the doctorate, the remaining two-fifths is composed of about two dozen other university degrees and non-university certifications [Fig. 4]. Undoubtedly, DTP studies’ defining blend of scholarship and practice has led to this plurality, wherein the doctorate is normally received as preparation for academic research and teaching, while the remainder of the degrees and certifications are largely preparation for practical work. However, the proportions differ when English, DTP, and interdisciplinary appointments are separated out [Fig 5]. Whereas only one-third of DTP faculty employed at DTP departments hold the doctorate (and one-quarter the MFA), a decisive nine-tenths at English departments hold the doctorate. Among DTP faculty appointed to interdisciplinary departments or cross-appointed to multiple departments, nearly three-quarters hold the doctorate.

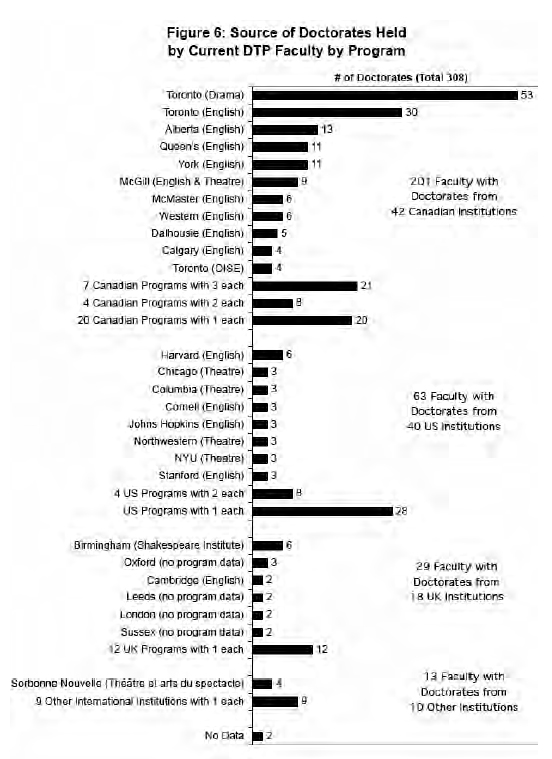

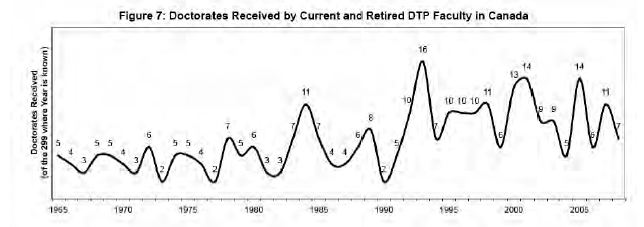

- Among DTP faculty with the doctorate, from where, in which discipline, and when did they obtain it, and where are they currently employed? Concern circulating among faculty and students in the humanities regarding the source of the doctorate (foreign or homegrown) as evident in the Graduating Professionals Forum, the Murray Report, and the Groarke and Fenske survey is arguably symptomatic of Canada’s long-running and highly complex identity positioning in relation to the United States and Europe. Are we willing and able to hire "our own" and do we make our own students competitive (and successful) in our own job markets? Or, is variety among sources of degrees more crucial to the health of disciplines in this country? In fact, the breakdown of doctorate sources among DTP faculty who hold that degree suggests some variety among source countries [Fig. 6]. Two-thirds of all DTP faculty with the doctorate (201) earned it from Canadian universities, one-fifth earned it from US institutions, one-tenth from UK institutions, and less than one-twentieth from institutions elsewhere in the world. Nevertheless, the number of distinct source programs balances out internationally: represented are 42 Canadian programs (including 5 distinct University of Toronto programs), 40 US programs, 18 UK programs, and 10 programs from elsewhere in the world. Thus, while there are, of course, more doctoral DTP programs to be found outside of Canada than within, among current DTP faculty with the doctorate most earned the degree in Canada. However, when the data field is widened to include all DTP faculty regardless of highest degree, Canadian-source doctorates amount to only two-fifths of all current DTP faculty employed in Canada. In other words, the majority of faculty (three-fifths) teaching DTP at Canadian universities does not hold a doctorate from a Canadian university. In what discipline were these doctorates earned? Nearly half of all doctorates held by current DTP faculty in Canada are from English studies, while just over one-quarter are from DTP studies. Rather than indicating that a DTP studies doctorate holds less potential than an English studies doctorate, this distribution may simply reflect a larger proportion of English studies drama graduates available to the job market over the past half-century. The University of Toronto leads the way among all source institutions, accounting for more than one-quarter of all doctorates held by current DTP faculty in the country: one-sixth earned it from the Graduate Centre for Study of Drama and another one-tenth earned it from the Department of English. Among foreign programs, Harvard’s Department of English and Birmingham’s Shakespeare Institute are the most prevalent, though their numbers are relatively slight with each accounting for barely 1 in every 50 doctorates held. Of data for doctorates earned as far back as 1965 by current as well as (web-listed) retired DTP faculty, half were completed in 1994 or later and nearly one-third since 2000 [Fig. 7].6 Of current DTP faculty with the doctorate as their highest degree, only 45 have both the year of doctoral completion and year of hire available. Of these, 17 completed the doctorate between 2000 and 2009; nearly half were hired within one year (or earlier) of completion. This is higher than the same one-year-or-less hire rate in both the 1990s (one-third) and the 1980s (also one-third).7

- Among DTP faculty with the Master of Fine Arts as their highest degree, from where did they obtain it, and where are they currently employed? The report found that DTP faculty who hold an MFA practise an array of specializations that includes directing, design, scenography, playwriting, creative writing, acting, voice and speech, "drama," and "performance." Most (about two-thirds) of the current DTP faculty who hold the MFA as their highest degree earned it from a Canadian university (NB same rate as for the doctorate), as compared to one-quarter who earned it from a US university (c.f. one-fifth for the doctorate).

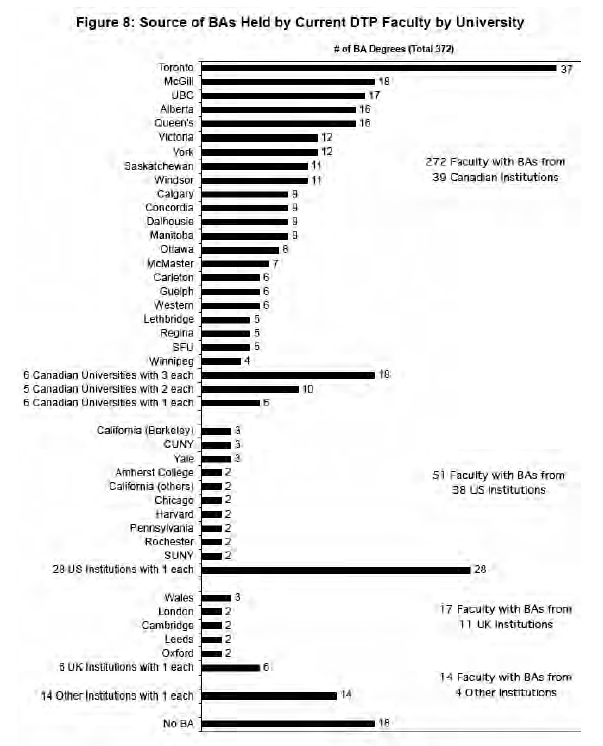

- From which countries and institutions did DTP faculty obtain their Bachelor of Arts degrees? Seven out of 10 current DTP faculty earned a BA degree (inclusive of Honours, General, and Combined BA degrees) for which data is available (about one-quarter do not list a post-secondary degree below the Masters level). More than three-quarters of all known BAs were earned at Canadian universities [Fig. 8]. As with the doctorate, the BA (any discipline) was most often earned from a program at the University of Toronto (about 1 in every 10). The balanced ratio between national and international distinct source institutions for the BA is also comparable to that for doctoral programs: 39 Canadian institutions, 38 US, 11 UK, and 4 elsewhere in the world.

- How many current DTP faculty were hired by the same university at which they pursued their highest degree? Few issues are as polarizing as the debate over whether or not a university should hire its own. After committing oneself for half-a-decade (or more) to a university while pursuing one or more degrees, it can be demoralizing for a graduate to be overlooked for a faculty position at that same university with which she or he is so familiar; conversely, an unsuccessful external applicant may feel embittered if sensing the decision had been made before a job was posted when an internal applicant is chosen. In fact, the report found that just 3 out of every 25 current DTP faculty are employed at the same university at which they completed their highest degree. This breaks down to one-tenth of those with the doctorate and one-quarter of those with the MA as the highest degree. About 7 in every 50 faculty who hold the MFA as the highest degree were hired by their MFA alma mater, but this lower number is no doubt accounted for by the fact that the MFA is often sought to earn training and credentials for practical theatre work and not necessarily for immediate positions within the academy. Many MFA graduates go on to national or international careers before teaching at universities (if they ultimately do so at all). Of note, 6 of the 10 DTP faculty who hold the BA as their highest degree are employed by the same university at which they earned it; 2 of the 7 who hold the BFA as their highest degree are employed by their BFA alma mater.

-

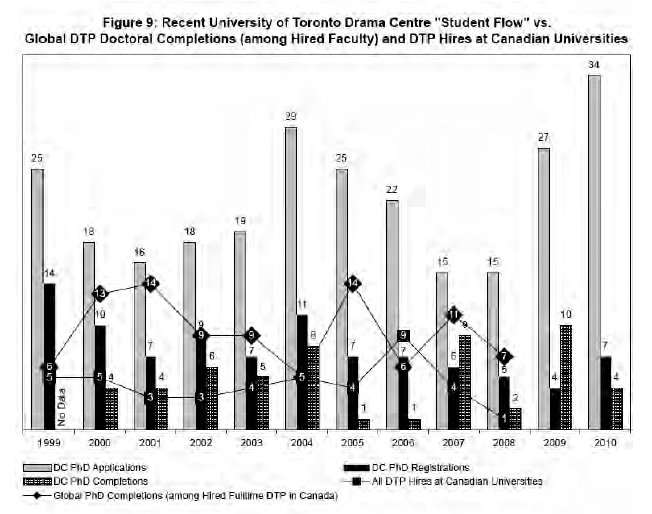

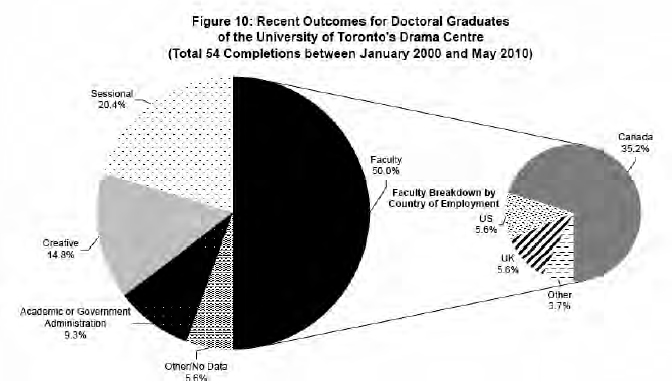

What is the recent impact of the University of Toronto’s Graduate Centre for Study of Drama on DTP studies in Canada? According to the Council of Graduate School’s PhD Completion Project, which studied doctoral completion rates at research universities across Canada and the United States, There is a general acknowledgement that studying in the humanities is more individualistic and is done more in isolation [than in other fields]. And funding for graduate students is lower in the humanities, so students are more likely tempted to abandon the PhD program and move on to a good job. (Susan Pfieffer qtd. in Strauss)The PhD Completion Project tracked cumulative completion and attrition rates for each year of doctoral work up to ten years. For example, it found that by year four of a humanities doctorate only 6.6% of students had completed and 19.4% had dropped out; by year five 12.4% had completed and 22.0% had dropped out; and by year ten 48.9% had completed and 32.7% had dropped out (Council, "Table 4"). For "Arts - History, Theory and Criticism" and "English Language and Literature" in particular, the year ten completion rates fall close to the overall humanities rate: 52.0% and 49.8% respectively (Council, "Table 9"). The Project’s overview states that "Research has shown that the vast majority of students, including minority students, who enter doctoral programs, have the academic ability to complete the degree," but that six "institutional and program characteristics emerge [. . .] as key factors" that influence a student’s ability to complete: selection, mentoring, financial support, program environment, research mode and the field, and processes and procedures (Council, "Project"). These numbers illustrate broadly one aspect of "student flow" at doctoral programs that directly feed faculty hiring across the continent, and they provide a backdrop for the present report’s findings. When Shelly Scott singled out the Drama Centre in her 1998 forum piece, her justification was that "The Drama Centre is by far the largest graduate drama programme in Canada" (202). More than a decade later this remains true. More specifically, it receives extended attention here because it admits and graduates more doctoral DTP students than any other program in the country and it has been doing so for much longer than any other program (since 1966). Moreover, its doctoral program is the largest single source for current DTP faculty in Canada [see Fig. 6] and the largest single source for current DTP faculty regardless of highest degree. By tracking "student flow"—that is, the number of annual applications, admission offers, new registrations, degree completions, and subsequent hires—during the past decade, the report traced the current impact of the Drama Centre’s doctoral program on the discipline in Canada.8 Over the past decade, between 40 and 60 doctoral students were registered there at any given time. During this period, its "student flow ratio" (applications : registrations : completions) was 263 : 94 : 54 (reduces to 4.8 : 1.7 : 1.0) [Fig. 9]. Thus, of 263 applicants, just over a third of that number (94) accepted offers and registered, and just over half the number who registered (54) completed during this time. (Notably, this rate is almost 8.5% higher than the year-ten completion rate across the humanities cited above.) By adding the number of national and international tenure-stream hires (27) to the end of the equation the flow ratio becomes 9.7 : 3.5 : 2.0 : 1.0. Thus, 2 of every 7 students who entered the program not only completed it but were also hired to a faculty position, and nearly one-tenth the number of program applicants was subsequently hired to a faculty position during this time [Fig. 10]. Half the number of students who completed the program found faculty positions (most at Canadian universities); one-fifth have sessional teaching positions (all in Canada); and one-third have found work in creative, administrative, or "other" non-scholarly fields.9 There is some variety in the specializations pursued by Drama Centre students. During this period, those who graduated had most commonly completed dissertations on the following topics: Canadian DTP (5 of 12 are now faculty), Shakespeare (3 of 6 are now faculty) and twentieth-century DTP (2 of 4 are now faculty). These "most common" specializations echo those "scholarly" specializations most commonly pursued among all current DTP faculty [see Fig. 2]. Looking ahead, whether the Drama Centre will maintain its influence on Drama, Theatre, and Performance studies in Canada is a matter for speculation. Unlike other DTP doctoral programs in Canada—such as the one offered at one time at the University of Alberta—the Drama Centre has consistently admitted and graduated doctoral students. In addition, during the past decade, three new programs emerged: a doctorate in Performance Studies at the University of Calgary dissolved shortly after its inception in 2006, the University of Guelph and Wilfrid Laurier University’s joint PhD program in Literary and Theatre Studies in English has recently shed its Laurier component, and the Theatre Studies program at York University began admitting doctoral students in 2006.

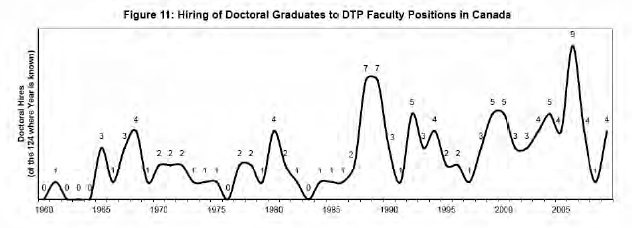

- What overall hiring trends are evident for DTP faculty in Canada? Of 565 current and retired DTP faculty hired since 1960 almost two-thirds (338) hold the doctorate, a portion somewhat greater than today’s current employed DTP faculty [c.f. Fig. 4]. Of these, about one-third (124) indicate their year of appointment to their tenure-stream position. Though this sample is relatively low, moderate hiring spikes are evident about twice every decade (except during the 1970s) [Fig. 11]. The fact that the year 2006 presents the largest hiring spike of all years among current and (web-listed) retired faculty could be explained by the fact that the "baby boom" generation was expected to enter retirement just as mandatory retirement was eliminated in Ontario (December 2006), Newfoundland and Labrador (May 2007), Saskatchewan (November 2007), British Columbia (January 2008), and Nova Scotia (July 2009) ("Mandatory").10 Of all current DTP faculty (i.e. excluding retired faculty) whose year of hire is available (107), one-third were hired during the past decade (after 2000). Three-quarters of these are appointed to DTP departments and one-quarter to English departments (compared to the half versus one-third ratio dating back to 1965). During the same decade just over half of hired DTP faculty held the doctorate, three-fifths of whom obtained it in Canada (primarily from the Drama Centre or McGill University) and one-third of whom obtained it in the UK or the US. A total of 19 distinct programs are represented among DTP faculty hired during this ten-year period. If this small sample were to be indicative of the full range of doctoral hires during the past ten years, we might speculate that the two-thirds majority of Canadian-earned doctorates across the last forty years may be eroding (to three-fifths or less). This would follow the overall trend for English studies as articulated by the annual updates to the Murray Report. Of present significance, among the 27 Drama Centre doctoral graduates noted above who were hired to tenure-stream positions between 2000 and 2009, no more than 4 were hired in Canada between the 2006 DTP hiring spike and January 2010. The reasons for this drop may include a convergence of the post-2006 lifting of mandatory retirement in six provinces and the post-2008 recession to which many universities have reacted with hiring freezes or curtailments. Whether the hiring pace will pick up again in the near future, or whether those who graduated during this lull will be competitive for faculty positions several years after completing their degrees, remains to be seen, particularly in light of the fact that during the past decade nearly half of DTP faculty were hired within one year or less of completion [c.f. point 4 above]. And while the number of Drama Centre doctoral completions is approximately equal to the number of DTP hires in Canada in the first few years of the decade (where year of hire is known), later completion and hiring rates rose and fell significantly [see Fig. 9]. These changes did not occur in lockstep, nor are they apparently keyed to global doctoral completion rates. While the academy’s faculty and administrative members constitute the discipline’s internal structure and its power relations, there is no national or international rhythm to which these drums beat.11

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11