Articles

Girls in "White" Dresses, Pretend Fathers:

Interracial Sexuality and Intercultural Community in the Canadian Arctic

Abstract

In 1903-04, men and officers of the Era and the Neptune and local Inuit socialized extensively while the two ships wintered near Fullerton Harbour (Nunavut). Square dances, the most popular shipboard events, functioned as sites where racial differences were manipulated and enacted through social performance. Examining Inuit women’s choice to wear "white" clothing to these dances allows one to see a specific way that costuming and social performance facilitated intercultural sociability and interracial sexual relationships. Providing clothing that made Inuit women appear more "white" and teaching them square dances allowed whalers to contain, ostensibly, the threat posed by "going native" through miscegenation; however, the clothing also highlighted the women’s racial alterity. Non-Inuit men also produced social performances to facilitate interracial sexual liaisons: the relationships that whalers developed with Inuit women resembled the spousal exchanges practiced in many Inuit communities and their behaviour toward Inuit children mimicked the traditional behaviour of Inuit men toward their families. The sexual and social performances produced by Inuit women and non-Inuit men were recognized as "pretend" by those who witnessed and participated in them, but they also created an actual sense of intercultural community among whalers and Inuit. Considering the community as constituted through performance locates it as a specific site at which ethnicity, like gender, emerges as a performative rather than expressive marker of identity, demonstrating how racial and ethnic identities are "tenuously constituted in time [. . .] instituted through a stylized repetition of acts [. . .] through the stylization of the body" (Butler 519).

Résumé

En 1903-1904, l’équipage et les officiers des navires Era et Neptune ont noué des relations importantes avec les Inuits de Fullerton Harbour, au Nunavut, pendant que leurs vaisseaux y hivernaient. La danse carrée, l’activité la plus populaire à bord du bateau, permettait aux participants de manipuler et de représenter les différences raciales par le truchement de la performance sociale. En examinant le choix qu’ont fait les femmes inuit de se vêtir en « blanches » à l’occasion de ces danses, nous sommes en mesure de voir de quelle façon exactement le costume et la performance sociale pouvaient faciliter la sociabilité interculturelle et les rapports sexuels interraciaux. En donnant aux femmes inuit des vêtements qui leur permettaient d’apparaître plus « blanches » et en leur enseignant la danse carrée, les baleiniers ont pu, semble-t-il, se parer contre le danger menaçant de l’« indigénisation » par métissage; toutefois, les vêtements servaient également à souligner l’altérité raciale des femmes. Les hommes non-inuit se livraient eux aussi à des performances sociales pour faciliter les rapports sexuels interraciaux : les rapports qu’ont développés les baleiniers avec les femmes inuit rappellent les échanges entre époux que l’on voyait dans plusieurs communautés inuit, et leur conduite à l’endroit des enfants inuit évoque le comportement traditionnel des hommes inuit à l’endroit de leurs familles. Les participants à la performance sexuelle et sociale des femmes inuit et des hommes non-inuit, de même que les témoins, savaient que celle-ci était feinte, mais elle servait tout de même à créer un sentiment d’appartenance réel à une communauté interculturelle formée par les baleiniers et les Inuits. Voir la communauté comme étant constituée par la performance nous permet d’en faire un site dans lequel l’ethnicité, comme le sexe, fait fonction de marqueur performatif de l’identité, plutôt que marqueur expressif du même genre, et démontre comment les identités raciales et identitaires sont « constituées, fragilement, dans le temps [. . .] instituées par une répétition stylisée d’actes [. . .] par la stylisation du corps » (Butler 519, traduction libre).

1 On Christmas Eve, 1903, an eclectic group gathered on the D.G.S. Neptune, a Canadian ship deployed to the Arctic to conduct geological surveys, to "patrol the waters of Hudson bay [. . .] [and] to aid in the establishment [. . .] of permanent stations for the collection of customs, the administration of justice and the enforcement of the law" (Low 3). One reason the Neptune was sent north was to locate the Era, the lone American whaler wintering in the Bay that year, in order to ensure that it was complying with new customs regulations imposed by the Canadian government. The Neptune certainly succeeded: it was able to keep a close eye on the American whaler while the two ships spent the winter together near Fullerton Harbour, located approximately 650km northeast of Churchill, Manitoba. Over the winter of 1903-04, the men and officers of the two ships socialized extensively, and on Christmas Eve, the Era’s whalemen and local Inuit joined the police constables, scientists, crew, and officers of the Neptune to celebrate the holiday. Whaling captain George Comer described the evening in his diary:

1 Lorris Elijah Borden, the Neptune’s surgeon, adds to Comer’s observations in his own diary, noting that the evening began with a "big feed for the natives" (57) and that dancing was for "sailors & natives," not commissioned officers and scientific staff (Lost 58). The evening was enjoyable for all members of the shipboard community; however, two distinct celebrations took place: the crew, police constables,1 and Inuit were on the upper deck, enjoying a large meal and a dance, punctuated by the appearance of men dressed as Neptune and his wife, while the officers and scientists briefly appeared at the dance then retired to Low’s quarters to celebrate privately.2

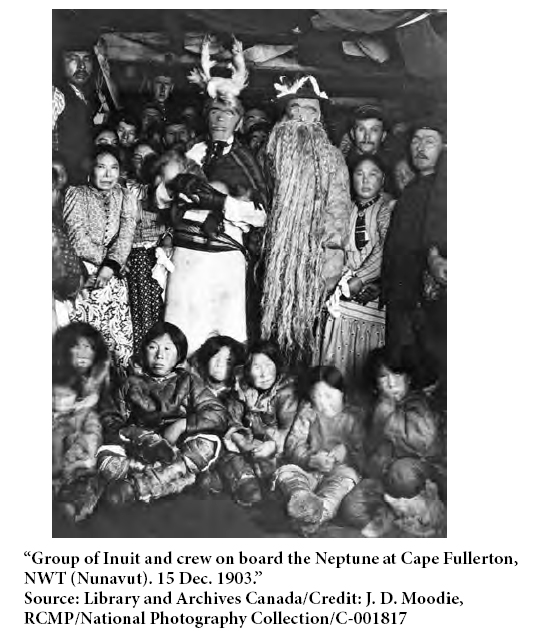

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 12 From Comer and Borden’s descriptions, it appears that this shipboard celebration was divided along lines of rank, with racial differences between Inuit and qallunaat (non-Inuit) being managed by grouping Inuit as part of the same social group as crew. A photograph taken to commemorate the festivities, likely taken by Major Moodie, the Royal Northwest Mounted Police Superintendent, not only provides an image of the celebrations but also hints, in a way that the diary entries do not, that the dance functioned as a site where racial differences were strategically manipulated and enacted through social performance.

3 The men dressed as Neptune and his wife draw the viewer’s gaze to the centre of the photograph because of their position at the focal point, their height, and their prominent costuming; however, if one instead focuses on the women on either side of them, another form of costuming becomes apparent, suggesting that racial difference emerges as a site of contestation at the dance.3 The women are wearing jackets and skirts made out of calico cloth in the style of "white" clothing, as opposed to the fur and skin clothing they often wore in photographs.4

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 24 The women’s choice to wear "white" clothing to this and other dances held during the winter, along with their participation in shipboard square dances, demonstrates one way that Inuit and non-Inuit relied on costuming and social performance to facilitate intercultural sociability and, specifically, interracial sexual relationships. By providing clothing that made Inuit women appear more "white" and teaching them square dances, whalers could ostensibly contain the threat posed by "going native" through miscegenation; however, the clothing also highlighted the women’s racial alterity and may have fetishized the women for the qallunaat men. Social performances to facilitate interracial sexual liaisons were not only produced by Inuit women for non-Inuit men: the relationships that many whalers developed with Inuit women resembled the spousal exchanges practiced in many Inuit communities, and their behaviour toward Inuit, particularly Inuit children, mimicked the traditional behaviour of Inuit men toward their families. The sexual and social performances produced by Inuit women and qallunaat men were recognized as "pretend" or "just a game" by those who witnessed and participated in them, but they also created a sense of intercultural community among whalers and Inuit and produced a number of real effects in Inuit society, including the spread of venereal diseases and the birth of a generation of children with non-Inuit fathers.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 35 Marvin Carlson grapples with three intertwined definitions of performance: as the display of skills, as the display of "culturally coded pattern[s] of behavior," and as the successful completion of an activity (70). The three examples of performance considered here—square dances, acting "white" or "Inuit" through culturally specific behaviour and clothing, and interracial sexual liaisons— correspond to Carlson’s triad; however, my argument is predicated not just on the conjecture that all three elements are performances but on the hypothesis that it is only by considering how these three forms of performance operated in relation to one another that one can understand how the intercultural community at Fullerton Harbour functioned. Furthermore, considering the community as constituted through performance locates it as a specific site at which ethnicity, like gender, emerges as a fundamentally performative rather than expressive marker of identity, demonstrating how racial and ethnic identities are "tenuously constituted in time [. . .] instituted through a stylized repetition of acts [. . .] through the stylization of the body" (Butler 519). My argument here may appear to be more concerned with performance generally than theatre specifically; however, it will become clear that race and gender were enacted and imagined through what Joseph Roach terms "effigying," a process of surrogation or substitution that "evoke[s] an absence" and "fills by means of surrogation a vacancy created by the absence of an original" (36). The ability to substitute one thing for another, according to Alice Rayner, is a fundamental characteristic of theatrical mimesis, which is based on "the very capacity to substitute one thing for another, to reconstitute a lost object in a present object, to transform the material objects of the world into imaginary objects, and the imaginary into the material" (129). Rayner argues, drawing on Carlson’s work in The Haunted Stage, that in the theatre, substitution occurs in an uncanny, ghostly manner and that this ghosting is critical to the phenomenological structure of all theatrical events: "The theatre itself gives appearances to the unseen, the hidden, and to the chronic return of the theatrical event from nothing into something. [. . .] In this sense, the ghost is not at all a metaphor for something else but an aspect of theatrical practice" (xvi-xvii). Theatre allows for a present object to substitute for a missing object but always preserves—and makes visible—the gap between the two. Examining the performative triad with which this article is concerned—of square dances, costuming and behaviour, and sexual performance—requires attention to the processes of substitution and surrogation and to the ghostly figure of the effigy: this allows one to locate these performances as fundamentally theatrical.

6 The intercultural community of whalers and Inuit developed at Fullerton Harbour near the end of a period marked by extensive contact between the two groups. A brief explanation of this era can be productively situated with reference to Mary Louise Pratt’s description of colonial contact zones. Contact zones are "social spaces where disparate cultures meet, clash, grapple with each other" (Pratt 4). By using the term contact, rather than frontier or border, one can foreground the "interactive, improvised dimensions of colonial encounters so easily suppressed by diffusionist accounts of conquest and domination" (Pratt 7). In 1860, American whaling ships began to winter in Hudson Bay,5 and 117 American and 29 British whalers entered the Bay during the period between 1860 and 1915 (Ross, Whaling 37). Inuit men and women quickly became involved in the whaling industry, assisting with the hunt, providing whalers with meat and warm clothing, and often continuing to hunt on behalf of whaling captains after they returned home at the end of the summer. The two groups grew highly dependent on one another, with Inuit coming to rely on the rifles, metal goods, and consumables that whalers paid them with and whalers counting on Inuit assistance to make the hunt profitable. Renée Fossett notes that although whaling permanently changed Inuit social and cultural life in many, often detrimental, ways, it also produced a number of effects Inuit felt were beneficial, such as increased access to tools, that made hunting more effective (169), and improved living conditions, in the form of limited medical care and a more stable food supply (170, 174). The relationship between the two groups was often a mutually profitable one and many whaling captains developed long-term relationships with Inuit, respected their customs and social arrangements, and reimbursed them fairly (Fossett 170,173). Harry Kilabuk, an Inuk man interviewed by Dorothy Eber, concurs with Fossett and remembers "[t]he qallunaat lived just like the Inuit, and they used to help each other out [. . .] when the Inuit were working for the whalers. [. . .] [E]ven though we were beginning to be run by white people, they were really happy, and enjoyed what they were doing" (qtd. in Eber 165). Locating the relationship between Inuit and whalers in the framework of Pratt’s contact zone allows us to foreground the idea that the relationship engendered by contact, particularly in its early stages, allowed for agency to be exercised by both groups.

7 The dances that occurred aboard the Era and Neptune, and the sexual relationships they helped facilitate, constitute part of a genealogy of performance, described by Joseph Roach as attending to "‘counter-memories,’ or the disparities between history as it is discursively transmitted and memory as it is publicly enacted by the bodies that bear its consequences" (26). In this genealogy of performance one can see the "highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination" (Pratt 4) that frequently characterize contact zones being, albeit temporarily, disrupted by social and sexual performances that enacted the possibility of a mutually beneficial intercultural community. It is particularly critical to pay attention to these performances—the dances and the sexual performances—because they occurred at a time when Inuit and non-Inuit lived and worked together in relative harmony: extensive contact had occurred but the detrimental effects of colonization had not yet begun to be felt.

Men at Sea

8 Shipboard sociability relied on the maintenance of a delicate balance of homosocial relations; this balance was threatened when men’s relationships with one another transgressed appropriate boundaries. In order to trace out how non-Inuit men’s relationships with each other are linked to square dances and interracial sexual relationships with Inuit women, it is essential to briefly outline how the two primary threats to shipboard sociability—homosexuality and mutiny—were understood and controlled.

9 Unsurprisingly, there are no statistics to indicate how frequently consensual or forcible homosexual relationships occurred on Arctic whaling ships; however, there is no reason not to assume that these liaisons were as common on Arctic whalers as on other whalers and, more importantly, that they were considered a threat to homosocial relations on Arctic whalers.6 John Winton claims "conditions in ships often encouraged sodomy: not only lack of women, but lack of leave and privacy, long sea passages, very crowded lower-decks and the close proximity of older men to young boys" (184-185). While it is difficult to reconstruct, as Winton attempts, precisely how homosexual relationships developed, his comment reflects the perception that homosexuality was relatively common aboard ships and that it was necessary for officers to be vigilant in preventing its occurrence. One only has to consult literary representations of nineteenth-century American whaling that address the threat homosexual desire posed, such as Melville’s Billy Budd, to see the intense anxiety that these relationships, real or imagined, provoked.7 William Eskridge Jr. notes that by the 1890s, Americans were obsessively concerned with the threat of homosexuality (40) and that "there was a revolutionary expansion of American sodomy law and its enforcement between 1881 and 1921" (50). One reason why consensual homosexual relationships may have been particularly problematic was that they could masquerade as "normal" male friendship, particularly because men were encouraged to relinquish their attachments to women at home and to form close bonds with their fellow crew (Creighton, "Davy Jones" 126). Many whaling captains recognized that in order to contain homosocial desire within appropriate boundaries, men needed an alternate sexual outlet: surviving records do not suggest that whaling captains, generally speaking, restricted "fraternization with Eskimos living near the ships" (Ross, Whaling 119).

10 Mutiny also posed a serious threat to shipboard sociability. Whaling captains believed that men developed antisocial and potentially mutinous desires when they grew bored with lack of activity, frustrated with poor living conditions, or irritated with their superiors. In the Arctic, serious rifts between men were a particular danger in winter, as Borden noted: "It had been known that when as few as two men were living together all winter expressions had become exhausted [. . .]. We were a much larger company but during the dark days we could observe little rifts developing which might have been serious had not remedies been taken to alter the situation" (Memoirs 82). Most concerning was when rifts developed along lines of rank, leading to overly close bonds between a group of crew or junior officers who could, often with little provocation, decide to mutiny. Comer explicitly referred to mutiny as a potential consequence of his men’s growing unhappiness with conditions on the Era compared with the Neptune; he wrote that the tension "would be as the point of a wedge, for a refusal to work and then would come mutiny" (105).

11 Dances were the most popular of the activities organized by Comer and Low to keep men distracted during the long winter. Low encouraged his men to participate in regular exercise and hunting expeditions and noted "[g]ames and cards were provided for the use of all; musical instruments [. . .] were in frequent use, while a weekly lecture, dance and newspaper went far to agreeably pass away the long winter evenings" (28). Borden recognized, however, that dances held a special place in shipboard social life: "it was the dances, held at intervals, which allowed everyone to shake off any inhibitions and thus remove those hostile attitudes which were developing" (Memoirs 84). Borden’s statement suggests that dances allowed men to "let off steam," releasing the tensions that arose from living in close quarters and preventing mutiny. It is significant that dances were also the only social activity sanctioned by the officers that relied upon the participation of women: this strongly suggests that dances contained both mutinous and homosexual desires.8

12 Although American seafaring involved men from a range of races and nationalities (Creighton, Rites 8) and whalemen were typically exposed to more non-white women than their contemporaries ashore, it is unlikely that white, American whalers were immune to racist attitudes or, more specifically, to the widespread anxiety that engaging in sexual relations with native women led to "going native."9 Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin note that the negative connotations of "going native" indicate

12 Anne McClintock adds that interracial unions were believed to represent "the paramount danger to racial purity and cultural identity in all its forms. Through sexual contact with women of color European men ‘contracted’ not only disease but debased sentiments, immoral proclivities and extreme susceptibility to decivilized states" (48). At least one member of the shipboard community at Fullerton Harbour shared these anxieties: Borden complained,

12 Borden’s observation that miscegenation was common is consistent with the historical record: although Comer is not known to have fathered any children while in the Arctic, he had a long-term relationship with an Inuk woman, Nivisinaaq. Whether Comer provided the "bad influence" or not, interracial relationships between whaling crew members and Inuit women produced many children: birth records Comer compiled indicate that of 36 children born near Fullerton Harbour between 1897 and 1911, 22 had non-Inuit fathers and 15 of these fathers were crew members on American whalers (qtd. in Ross, Whaling 122).

13 It is well documented that many whalers engaged in sexual relationships with Inuit women. Less attention has been paid, however, to how whalemen reconciled their sexual desires with widespread cultural anxieties concerning "going native." The archive tends to be silent on this issue, both because of taboos concerning interracial sex—Comer wouldn’t have dreamt of recording details of his relationship with Nivisinaaq in his diary, for example—and because the majority of men engaged in these relationships—crew members—kept no written records. While it is impossible to reconstruct the contours of sexual desire, one can speculate that the dances, and particularly the clothes Inuit women wore to the dances, allowed men to overcome the fear of "going native" by making their sexual partners "go white."

Girls in "White" Dresses

14 Inuit women had had limited access to "white" clothing since the 1850s, but these items, particularly rare pieces such as corsets, were highly coveted in the early twentieth century. Tackritow, who visited England in the 1850s, seems to have been the first Inuk woman to bring "white" clothing to the Arctic.10 She "stimulated a demand for imported items of clothing" and when whalers began wintering in the Arctic, they frequently brought American items—ball gowns, fancy hats, corsets, fabric, and ribbons—so that "during the winter the native women could appear at shipboard dances dressed like the girls back home" (Ross, Distant 138). Ross argues that "[t]hese articles had strong purchasing power as well. They could be traded for souvenir items of skin and fur [. . .] and were doubtless also offered in return for sexual favours," highlighting how material and sexual economies were intricately intertwined (Distant 138).

15 It is significant that women wore "white" dresses to dances: dances, as social performances, allowed Inuit women and non-Inuit men to enact membership in the same social group. Dances marked the participants, at least temporarily, as a group that shared a specific, embodied form of knowledge. Although neither Borden nor Comer described the dancing on Christmas Eve, Borden’s detailed description of a dance held to celebrate Thanksgiving provides a sense of what shipboard dances were like:

15 I have reproduced this passage in full in order not only to allow one to imagine what shipboard square dances were like but also to examine how Borden observed the women’s clothing. On Thanksgiving, Inuit arrived around 4:30, after the crew had eaten their dinner. Music began an hour after the Inuit began to arrive, so the two groups likely mingled while waiting for people to arrive and for the dance to begin. The dancing, which lasted almost six hours, was quite vigorous: the temperature on the crowded upper deck would likely have been below zero, so Borden’s comment that the police constable danced in his shirt sleeves indicates that he was dancing enough to work up a sweat. The dances were mainly lancers, a form of quadrille that originated in the late eighteenth century and evolved, in the United States, into a square dance performed by four couples (Chujoy and Manchester 750). The group that Borden found so noteworthy was racially mixed, including four Inuit women, a black sailor, and a "half breed." The police constable and sailor were likely white, since Borden did not find it necessary to remark upon their race. Borden’s careful clarifications of racial difference, his use of the terms "coon" and "half-breed," and his naturalization of whiteness as unremarkable indicate the extent to which the idea of white superiority was deeply embedded in his world-view; however, Borden saves his most pointed comments for the Inuit women. Although Borden says that the Inuit "danced fairly well," he found it difficult to describe their baffling "movements & looks," suggesting that the dance steps masked racial differences that were revealed not only by physical appearance but also by gestures and expressions. This suggests that the dances created a social situation in which the ability to participate successfully in the group performance linked the members, allowing racial differences to be temporarily overlooked. It is easy to imagine, for example, the two white dancers having fun, laughing, and forgetting or not caring that they were dancing with members of "inferior" races.

16 Although Ross suggests that the women wore "white" clothing in order to dress "like the girls back home" (Distant 138), Borden recognized that their clothes were an imitation of what American women would wear, both in terms of style and quality. To readers today, his complaint that the women’s dresses did not have low necks or trains and that they did not have bouquets of flowers may seem petty, and his criticisms of the women’s bodies as short, fat, and shapeless may seem offensive; however, this passage suggests something critical to understanding how some men might have viewed the women’s clothing. While it is plausible that wearing "white" dresses allowed Inuit women to "go white" and thus allow qallunaat men to avoid "going native," Borden’s recognition of the gap between the clothing and the women’s racialized bodies indicates that something else was also happening: the women’s failure to pass as white might have been precisely the point.

17 Joseph Roach uses the term effigy to describe a particular form of surrogation that evokes an absence by filling the vacancy created by the absence of an original (36). While we often think of effigies being made of wood or cloth, Roach makes the tantalizing suggestion that "more elusive but more powerful effigies" can be "fashioned from flesh" and "made by performances" (36). Inuit women in "white" clothing ostensibly functioned as effigies, replacing women at home by dressing, acting, and presumably fornicating like them. But Roach also tells us that surrogation "rarely if ever succeed[s]" because "the intended substitute either cannot fulfill expectations, creating a deficit, or actually exceeds them, creating a surplus" (2). The deficit created by the women failing to be "white" enough to pass, in Borden’s eyes, is critical.

18 Interracial sex was imagined as not only dangerous but also tempting. McClintock comments that

18 Ann Laura Stoler expands on this, arguing that "[t]he tropics provided a site for European pornographic fantasies long before conquest was under way, with lurid descriptions of sexual license, promiscuity, gynecological aberrations, and general perversion marking the Otherness of the colonized" (43). If one accepts that the same structure of desire operated in the Arctic, one can argue that sex with Inuit women both posed a threat which needed to be contained and aroused long-standing porno-tropical fantasies. The women’s "white" clothing could have allowed for these competing desires—for containment and eroticism—to be fulfilled simultaneously. The women ostensibly looked more "white," thus becoming more appropriate sexual objects, yet their clothing also highlighted their racial otherness, thus heightening the temptation of interracial sex. Homi Bhabha uses the phrase "almost the same, but not quite" to describe how colonial mimicry produces both similarity and irreconcilable difference (123); in this case, it appears that the Inuit women’s "almost the same, but not quite"-ness in their "white" clothing was precisely the point of encouraging them to wear the clothing since it allowed them to be figured simultaneously as almost civilized women and as promiscuous, taboo Others.

Pretend Fathers

19 Inuit women chose to wear "white" clothing, were willing participants in sexual relationships with qallunaat men, and benefitted economically and socially from these relationships. They were not, to borrow Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s wording, simply "objects of exchange," but were "users of symbols and subjects in themselves" (50). The interracial sexual relationships that developed were part of a larger economy in which each group depended on the other for material goods, services, and social support. The non-Inuit men who engaged in these sexual relationships were, as much as the women, performing an idea of racial identity in order to facilitate the sexual-social system. While examining whalers’ practice of wearing fur clothing is initially tempting, as it would lead to tidy parallels in this argument, men’s clothing choices do not seem to have been as central to Inuit’s acceptance of interracial sexual relationships as other forms of performance: first, the structure of interracial sexual relationships mimicked that of spousal exchanges practiced in Inuit culture and, second, non-Inuit men, intentionally or not, imitated gendered behaviours in a way that was recognizable to Inuit.

20 John Bennett and Susan Rowley draw together Inuit oral histories of the practice of spousal exchange:

20 Fossett emphasizes the importance of the kinship ties created by spousal exchanges:

20 Spousal exchanges were practiced during the winter of 1903-04; Commander Low noted that "[a]n exchange of wives is customary, after certain feasts, or after the angekok has performed his conjuring tricks [. . .]. These customs make polyandry easy where it is found necessary" (164). Low locates spousal exchange as part of spiritual practices but then seems to undermine the spiritual aspect of spousal exchange with his final suggestion that the ritual aspects make the practice easy to accept. He does not mention any non-Inuit involvement in the ceremonies; however, this omission does not mean that it did not occur: Comer did not remark upon his relationship with Nivisinaaq in his diary and it would have been even more inappropriate for Low to suggest in a report prepared for the Dominion government that interracial sexual liaisons occurred.

21 Knud Rasmussen’s interview with an Inuk woman, Takornaq, suggests that Inuit viewed interracial sexual relationships as an acceptable continuation of the existing practice of spousal exchange:

21 It is necessary to take his comment, and Low’s above, with a grain of salt: suggesting that Inuit women are not naturally monogamous might indicate that Rasmussen and Low are attempting to let qallunaat off the hook for infidelity to their partners at home and for potentially corrupting Inuit women through these liaisons.12 It does seem, however, that Inuit viewed interracial sexual relationships as a continuation of spousal exchanges and thus viewed them as economically and socially beneficial, because of the goods received in exchange for women and the creation of kinship relationships with whalers. While it is tempting to understand these exchanges as cuckoldry and thus to argue that they allowed qallunaat men to exercise power over Inuit men by sleeping with their wives, it is essential to remember that these relationships were not secrets in the intercultural community and that women were not simply exchanged but appear to have been agents in the exchanges.13

22 The example of Nivisinaaq and George Comer’s relationship demonstrates how interracial relationships were understood by Inuit and how women benefitted socially and economically from them. Nivisinaaq (also called Shoofly) was married when the relationship began but, according to Ookpik, an Inuk woman who was a child at the time, Nivisinaaq’s husband Tugaak "knew the captain had Nivisinaaq as a girlfriend, but they were real good friends to each other" (qtd. in Eber 115). Their relationship was acknowledged by the Inuit community, who "looked upon [them] as man and wife" (qtd. in Eber 114). Comer brought Nivisinaaq a sewing machine, making her the first Inuk woman to have one, and she often sewed dresses for friends and relatives (Eber 121). These clothing items are remembered by Eugenie Tautoonie Kablutok as "really useful" and were highly coveted: "People would keep the same dress [. . .] for about two summers [. . .] washing it carefully and making sure there were no tears" (qtd. in Eber 122). Nivisinaaq’s access to imported fabric and ability to sew it are among the things Inuit remember about her and marked her as "an innovator" and "a pioneer and trendsetter" (qtd. in Eber 121, 122). That she was regarded by Inuit as "one of the leaders among our people" and "a superior person" (qtd. in Eber 114) suggests that her relationship with Comer certainly did not hurt her social status; her access to desirable commodities likely improved it. The relationship between Comer and Nivisinaaq seems to have been a caring one, evidenced by Comer’s comment, shortly after returning from his last voyage, that "[w]e got attached to the natives" (qtd. in Eber 164) and by the report that "[u]ntil her death [in the 1930s] he continued to send her presents and, as John Patterk, a great-grandson says, ‘her pension’" (qtd. in Eber 123). Although Nivisinaaq is an extreme case, the benefits of interracial sexual relationships were well recognized, even by children.

23 Anirnik, who was a child at this time, recognized both how the economics of these relationships worked and the performative component of them. She remembers how

23 Anirnik’s recollection suggests that while children might not have been aware of the sexual component of their mothers’ relationships, they recognized that the whalers were acting like their fathers by bringing them food and by being paired up with their mothers. She also suggests that children were aware that these "pretend fathers" were acting outside the bounds of normal behaviour: rather than distribute food to all Inuit in a relatively equal manner, Anirnik hints that whalers gave special gifts and attention to their "pretend children," that is, the children of their Inuit partners. By bringing their "pretend children" food, crew members imitated Inuit men’s family roles; neither the children, nor their mothers, nor the whalers seem to have found it problematic that even the term "pretend fathers" suggests that the whalers were standing in for the children’s biological fathers. Although food shortages were less common by the early twentieth century, starvation was still a real threat to Inuit populations: providing the children of sexual partners with food—in other words acting like Inuit men—links the sexual and subsistence economies through the qallunaat men’s performances.

24 While it is impossible to establish whether Inuit women and non-Inuit men explicitly understood their actions as performative, Anirnik’s recognition of the "pretend" quality of the men’s behaviour suggests that it is productive to link these events—the Inuit women donning "white" clothing and participating in square dances, the structural replication of spousal exchanges, the non-Inuit men acting like fathers—within the structure of the performance genealogy. Locating this genealogy in terms of colonial mimesis helps clarify the relationship between performance, interracial sexuality, and intercultural community further. Michael Taussig argues that mimesis in colonial paradigms can be "understood as redolent with the trace of that space between [. . .] so mimesis becomes not merely of [an] original but by an ‘original’" (79). Inuit women and non-Inuit men were not simply imitating what they thought members of the same gender in the opposite race were like, but actually creating a new form of colonial subjectivity: Inuit women did not become white by dressing in "white" clothing and qallunaat men did not become Inuit by having sex with Inuit women or acting like Inuit men; however, these performances created a group of subjects who knew race on the level of an embodied, improvised, strategic performance. A new form of colonial subject was created on a biological level as well: one must remember that these relationships produced a generation of children with non-Inuit fathers and Inuit mothers, blurring the line between make-believe and reality and bringing to mind Bert O. States’s well-known observation on the phenomenology of theatre: "in theater there is always a possibility that an act of sexual congress between two so-called signs will produce a real pregnancy" (20).