Articles

Amy Sternberg’s Historical Pageant (1927):

The Performance of IODE Ideology during Canada’s Diamond Jubilee1

Abstract

In 1927, sixty-five chapters of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) staged Amy Sternberg’s Historical Pageant in Toronto to celebrate Canada’s Diamond Jubilee. Accessing primary source documentation, this article argues that Sternberg’s production constructed and conveyed IODE ideology by placing female agency in the service of liberal imperialism. Specifically, the female allegorical and historical characters in the pageant provide an index of values that emphasized the role of women in creating a strong Canada closely aligned with a venerated British Empire. Beyond the script and the stage, the program for the production and press clippings suggest that the IODE used Historical Pageant to promote itself as a modern organization in which female leadership fostered civically engaged action while simultaneously and subtly re-inscribing the traditional hierarchical social structure of the British Empire within Canada. In these ways, Historical Pageant reminds historians of the necessity to consider how theatre has been used by Canadian women to assert their political views publicly even when those views espouse ideology that is no longer acceptable.

Résumé

En 1927, soixante-cinq sections locales de l’Ordre impérial des filles de l’Empire (IODE) ont mis en scène le Historical Pageant de Amy Sternberg à Toronto pour célébrer le jubilé de diamant du Canada. Dans cet article, l’auteure fait valoir, à partir de références documentaires de première main, que le défilé historique de Steinberg a servi à construire et à communiquer l’idéologie de l’IODE en mettant l’action des femmes au service de l’impérialisme libéral. Plus précisément, les personnages allégoriques et historiques de sexe féminin mis en scène dans la production constituent un répertoire de valeurs qui met l’accent sur le rôle des femmes dans la création d’un Canada fort, en conformité avec le vénérable Empire britannique. Au-delà du scénario et de la mise en scène, le programme de la pièce et les articles parus dans les journaux laissent entendre que l’IODE s’est servi du Historical Pageant afin de se promouvoir en tant qu’organisme moderne au sein duquel les leaders de sexe féminin invitaient la population à l’engagement civique tout en reproduisant subtilement la hiérarchie sociale traditionnelle de l’Empire britannique au Canada. Ainsi, le Historical Pageant rappelle aux historiens qu’il faut voir comment les Canadiennes se sont servies du théâtre pour affirmer publiquement leurs opinions politiques, même quand ces dernières endossent une idéologie devenue désuète.

1 In 1927, Amy Sternberg, one of Toronto’s most successful dance teachers and choreographers, wrote and directed Historical Pageant. Staged as part of the celebrations marking Canada’s Diamond Jubilee, the production premiered at Massey Hall in Toronto on Wednesday, 22 June and was performed for three consecutive nights plus a Saturday matinee ("IODE Pageant"; "Municipal"; "Toronto"). The pageant, which received significant press coverage, featured Sternberg’s students, a few of the Hart House players, members of the Navy League, school children, and community members ("Children"; "Gowns"; "Toronto"). The majority of the over 500 performers and the approximately 3,000 production personnel, however, belonged to sixty-five chapters of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE), which produced the pageant under the aegis of its Toronto Municipal Chapter, working in conjunction with administrators for the city of Toronto who were coordinating civic activities in honour of Canada’s sixty years of Confederation ("Progress"; "Three Thousand"; "Toronto").

2 In briefly addressing Sternberg’s pageant in his article about Canada’s Diamond Jubilee festivities, Robert Cupido argues that federal attempts to use the anniversary to unite the country through the rallying of nationalist sentiments were co-opted by the conflicting agendas of organizations like the IODE, which used Historical Pageant to stage their "obliquely imperialist orientation." ("Appropriating" 178).2 Moreover, as Cupido notes, specifically referencing Sternberg’s production, "apart from highlighting the isolated and exceptional exploits of a few exemplary heroines like Laura Secord and Madeleine de [Verchères], Canadian women were still devoting most of their talents to commemorating the nation-building achievements of men" (179).

3 It is true that Historical Pageant, which consists of nine scenes and accompanying tableaux vivants, idealized Canada’s colonial relationships; presented Canadian history as an uncomplicated parade towards modernity and dominion status; and implied that the country had been shaped primarily by men like Jacques Cartier, Samuel de Champlain, Generals Wolfe and Montcalm, and the Fathers of Confederation. Nevertheless, Historical Pageant requires a more in-depth consideration of the nuanced understanding of Empire and gender politics that underpinned the production and defined the IODE in 1927. Certainly, the organization strongly advocated allegiance to the British crown, but this fidelity did not preclude patriotism for Canada. In this way, Historical Pageant was aligned with the liberal imperialism that was commonplace in Canada at the time. While the scenes included in Historical Pageant primarily valorised male explorers, military men, and politicians, the very act of producing the pageant was an assertion of female agency. Moreover, the female characters in the pageant, though outnumbered by their male counterparts, were still dramaturgically important because they conveyed ideals associated with the IODE at the time. The backstage dominance and activities of women are particularly worth examining because they communicated IODE priorities such as providing female civic leadership. In other words, just because the ideals of nation and history furthered by Sternberg and the IODE reified, instead of challenged, the traditional and dominant ideologies, the issue of how these women used theatre to stage their political beliefs should not be negated or ignored. On the contrary, although for many theatrical professionals, the stage is a liminal arena where it is possible to play with and transgress—if only temporarily—established cultural values and to rehearse alternatives perceived as more progressive, we should not forget that the arts are equally available to iterations of the status quo and agendas resistant to social change.

4 Post-colonial scholarship in the arts has often focussed on the subversion of imperialism by colonial subjects, while how some of those subjects willingly facilitated the continuation of imperialism has arguably received less attention. Within this scholarly context, the goal of this article is neither to defend the concept of Empire nor to disclaim the fact that the vision of Canada and its past as staged in Historical Pageant was not shared by most French Canadians or by those English Canadians who, in 1927, advocated for more political independence for the Dominion. Instead, my objective is to position Historical Pageant in response to Philip Buckner’s appeal for more research examining how and why average citizens participated in the perpetuation of the British Empire in Canada during the twentieth century through a variety of cultural and ideological ways:

4 Buckner is particularly interested in how interwar imperialism led to Canadian support of the British at the beginning of World War II, but his comments also invite a consideration of how and why "ordinary English-speaking" Canadian women used theatrical performance to assert their political views publicly.

5 Happily, a significant cache of archival materials related to the production has been saved. Although a complete script has not been found, the program for Historical Pageant contains a detailed synopsis of the pageant and the tableaux vivants. Other archival documents include portions of a draft manuscript outlining some of the scenes. A brief familial memoir that illuminates Sternberg’s private life and a remembrance about Sternberg written by a former student are also accessible. Numerous (though often fragmented) newspaper clippings, programs, and brochures related to Sternberg, her school, and her artistic activities also survive. The history of the IODE in Canada is well documented and the organization’s interest in the Diamond Jubilee is discussed in the pages of Echoes, its quarterly magazine.

6 Basing my analysis largely on these primary sources, I begin by briefly introducing Sternberg and her involvement in the creation of Historical Pageant before situating the production within the interwar liberal imperialist sentiments that prevailed in English Canada at the time—sentiments that simultaneously accommodated both domestic and imperialist allegiances. The remainder of the article examines the intersections of gender, theatre, and Empire that Sternberg and the IODE used to further their campaign to promote the importance of women in forging a proudly robust Canada in the service of a fortified and glorified British Empire.

7 Sternberg’s pageant transmits IODE’s philosophy in a variety of ways. It becomes apparent, for instance, that traditionalism not only defined the affinity Sternberg and the IODE had for maintaining the status quo politically, but also characterized Sternberg’s dramaturgical approach. Her strategy of using the stage to voice political views echoes the work of earlier women in Canadian theatrical history such as Sarah Anne Curzon and Edith Lelean Groves, among others.3 Similarly, in writing the script for Historical Pageant, Sternberg closely followed the standard practices for the historical pageant genre while simultaneously stressing IODE political views. As in many other historical pageants, for instance, Historical Pageant featured women embodying allegorical political entities that symbolically equated women with countries. In Sternberg’s pageant, this symbolism accentuated the closeness of Canada’s relationship to Britain. In addition, Sternberg’s portrayal of the historical female characters included in Historical Pageant, particularly Laura Secord, Madeleine de Verchères, and the Ursuline nuns, may be interpreted as the staging of the feminine ideals promoted by the IODE—ideals that cast women as protectors of home, country, and King. Finally, acknowledging that the construction and conveyance of ideological positions is not limited to onstage activities, but extends to all facets of theatrical productions, this article moves beyond the script to consider how Historical Pageant and the material conditions of its production "performed" the IODE and promoted its values. In its dealings with the Toronto media, for instance, as well as in the program for Historical Pageant, the IODE portrayed itself as an organization defined by modern and civically engaged female leadership. At the same time, however, this gender-specific self-depiction subtly minimized the exclusivity of the IODE’s class-based membership—a stratification that replicated and re-affirmed the traditional hierarchical social structure of the British Empire within Canada.

8 The aggregate importance of these various aspects of Historical Pageant, its production and the organizational context is the facilitation of a fuller understanding of how, in 1927, the duel allegiance to nation and Empire provided a platform for some women in Canada to assert their political views in the public sphere a decade after female agency had gained political traction through federal electoral emancipation and sixty years after Confederation.4 The goal of these women, which was to perpetuate ideas that are undesirable and untenable within Canadian society at the beginning of the twenty-first century, should not deter historians from attempting to understand why Sternberg and her colleagues in the IODE believed that theatre could function as an effective medium for their political agenda.

Setting the Stage

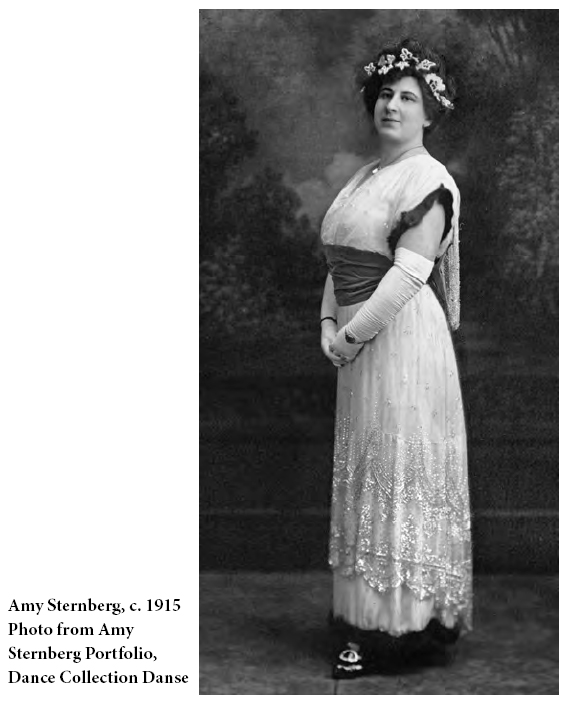

9 Born in Montreal in 1876, Sternberg and her older sister Sarah studied physical culture at Miss Barnjum’s Gymnasium before Sarah secured the patronage of Lady Aberdeen, the wife of the newly appointed Governor-General, and opened her own physical culture school in Toronto in 1893 (Warner 55). Sternberg joined as a teacher the following year and, by 1910, was the sole director of the school, which had added dance to its curriculum around the turn of the century.

10 During the 1910s and early 1920s, Sternberg instructed hundreds of students every year; and her year-end recitals annually filled the 3,500-seat Massey Hall on two consecutive nights. In the late 1920s, Sternberg’s studio offered classes in "classical" and "national" dancing for children as well as adults, which led to the performance of choreographic works like Air de Ballet and Spanish Dance in the yearly recitals ("Recital"). Other types of instruction included acrobatic, tap, toe (i.e. pointe work), and ballroom dancing ("Miss Sternberg," Brochure). Her students were often hired to perform as professionals in the large, lavish, and interdisciplinary productions that she staged for the annual Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) Grandstand Shows (Warner 61; Tilly; and "Dance"). One student, Eric Forbes, found employment in the Denishawn Company in the United States. Another, Helen Codd, was appointed the director of the Vaughan Glaser Repertoire Company, which was featured at Loew’s Uptown Theatre in Toronto during the 1920s (Warner 61).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 111 Sternberg was particularly interested in pedagogy. In addition to offering technique classes at her studio, she created a two-year teachers’ training program whose graduates found work as dance and physical culture teachers ("Miss Sternberg," Brochure). Sternberg’s own talents as a teacher were so highly in demand that by 1919, in addition to her own studio, she also taught at the Canadian Academy and College of Music, the Hambourg Conservatory of Music, St. Andrew’s College, the Toronto Conservatory of Music, and Upper Canada College (Warner 61).

12 Although it is uncertain if Sternberg was a member of the IODE, she maintained close ties to the organization.5 Advertisements for her studio appeared in the IODE’s Echoes ("Miss Sternberg," Advertisement). Her students were billeted in the homes of IODE members when they toured Ontario in a production of Sternberg’s choreographic work, The Gypsy Maid (Warner 61). The IODE was also one of the sponsors of the 1915 pageant Fantastic Extravaganza—a fundraiser for the Red Cross during World War I, which was performed in Toronto at Massey Hall to packed houses and appreciative critics ("Fantastic"). Sternberg was a central member of the creative team for Fantastic Extravaganza in her role as the main choreographer, which—like the CNE productions—required the choreographer to work with large numbers of performers on stage at the same time ("300 Performers").

13 Sternberg’s participation in Historical Pageant was one of the factors that distinguished the production from the other pageants created for the Diamond Jubilee in Canada, making it one of the few to be written and staged by a Canadian dance professional. While it is unknown when or how Sternberg became involved with the Historical Pageant project, as early as the IODE’s 1926 Annual Meeting, the Provincial Chapter of Ontario suggested that the IODE stage an historical pageant in honour of Canada’s Diamond Jubilee ("Report of the Annual"). Sternberg’s well-established association with the IODE and her proven ability to choreograph for and direct large groups of performers with varying levels of training and stage experience made her an obvious choice for the job.

14 Sternberg possibly based some of her script for Historical Pageant on a list of scenes from Canadian history published in the December 1926 issue of Echoes that had been recommended for Diamond Jubilee pageants by IODE’s National Committee ("Recommendations").6 As suggested in the Echoes article, for instance, Sternberg began her pageant with a depiction of Jacques Cartier’s encounters with indigenous people in 1534. She followed this with the first tableau: "A Day of Good Cheer, 1606," in honour of the founding of the Order of Good Cheer in Port Royale, highlighting European ingenuity in overcoming the hardship of colonial life through communal entertainment; the theatricalized culinary feast signified the triumph of European civility over the inhospitable wilderness of New France.

15 In the next scene, Sternberg moved away from the recommendations printed in Echoes to create "The First School," which featured indigenous and French children together in a classroom under the tutelage of a teacher played by a woman who was a member of the John Ross Robertson Chapter of the IODE in Toronto. As if to animate the deeds of the Europeans whom the pupils might have encountered in their lessons, the second tableau was "Henry Hudson Discovering the Hudson’s [sic] Bay."

16 The third scene was set at a ball at the French court at Quebec under Buade de Frontenac et de Palluau that was performed by the Rosedale IODE Chapter along with dancers from Sternberg’s studio. In the script, the festivities are disrupted when a messenger arrives with news of an impending attack. The theme of the threat to the colonies was paralleled in the accompanying tableau, "Madeleine de Verchères, 1692," which depicted Marie-Madeleine Jarret de Verchères, a young woman who led a successful defence of her family’s seigneury against the Iroquois.

17 The Sanctuary Wood Chapter, in conjunction with a chorus of dancers from Sternberg’s school, then performed Longfellow’s poem "Evangeline" to tell the story of the Acadians, whom Sternberg called "unfortunate if misguided people" (Historical Pageant 48). Afterwards, members of the IODE’s Lord Nelson Chapter hurried on stage to take their places in the fourth tableau, "Ursulines Landing at Quebec," a tribute to the religious order of women who arrived in New France in 1639 to educate aboriginal and French children.

18 It is odd that a production staged by the IODE would venerate French historical figures. Yet, the "Recommendations for Celebration of the Jubilee of Confederation," encouraged the inclusion of scenes from New France. It is also possible that the successful 1908 tercentenary pageant staged in Quebec City and which marked the founding of Quebec, inspired Sternberg as she wrote Historical Pageant. In the script for her pageant, as in the text for the 1908 Quebec pageant, Jacques Cartier raises a cross and the Fleur-de-Lis of France, humbling the gathered natives. The Ursuline nuns also are featured prominently in both pageants (Nelles 34).7 Whatever Sternberg’s motivation, one of the effects of her choice to set a significant number of scenes in New France was that the political tensions between French and English citizens that had been exacerbated by the conscription crisis of World War I were smoothed under a pan-Canadian revisionist view of history.

19 The fifth scene was one of the pageant’s most ambitious—a re-enactment of the battle of the Plains of Abraham. The scene began in dim light with, as one reviewer described, "the scarlett-coated figures" upstage as a voiceover recited Thomas Grey’s "An Elegy Written in a Country Church Yard." The scene culminated with the deaths of Generals Montcalm and Wolfe, the staging of the latter based on Benjamin West’s painting, The Death of Wolfe ("Children"; "People"). Jumping ahead in time, Sternberg paired this scene with "Alexander MacKenzie Discovering the Pacific Ocean," a tableau of the first European explorer to reach the Pacific Ocean by crossing land north of Mexico in 1793.

20 In theatricalizing life in the British colony, Sternberg extolled Canada’s role in the Underground Railway and the virtues of the United Empire Loyalists in the prologue to Scene Six, a scene depicting the first elected Assembly under Governor Simcoe, the first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada. Sternberg named the sixth tableau "Meeting of Brock and Tecumseh"—perhaps a reference to the same-titled 1920s illustration by the artist C.W. Jefferys. (In fact, it is possible that in creating her series of tableaux, Sternberg was inspired by an exhibition of Jefferys’s paintings of scenes from Canadian history that had been on exhibition in Toronto in honour of the Diamond Jubilee and which were published in a handbook intended for teachers, but also advertised as "invaluable to those who are planning Canadian plays and pageants" Pease 10).

21 This tableau set the stage for Scene Seven, a reenactment of the War of 1812. In her Prologue to this scene, Sternberg proclaimed that once the news of war spread, the colonists upheld their duty to the British crown and "the plough gave once more to the sword [sic]" (Historical Pageant 75). The ambitiousness and dramaturgical importance of this scene was underscored by the large number of onstage performers representing fourteen chapters of the IODE and portraying farmers and their families ready to fight against the Americans. This scene was twinned with the next tableau: Laura Secord informing the British of the impending American attack.

22 The evening continued with a scene Sternberg called "Homesteading the West," in which hardworking colonists "settled" the West, even though—as Sternberg noted in her Prologue—the westward movement of the Europeans disrupted the claim to the lands held by the indigenous and Metis populations (Historical Pageant 82-83). The performance of a "down-home" dance, replete with a fiddler, was followed by a more formal scene in the eighth tableau: "Fathers of Confederation." This tableau was modeled after Robert Harris’s 1884 painting Conference at Québec in 1864, to settle the Basics of a Union of the British North American Provinces (also known as The Fathers of Confederation). One by one the actors portraying the Fathers of Confederation rose from the tableau and recited brief excerpts from the Confederation Debates ("People"; and "Progress").8 When the actors finished, the curtain closed and then rose again to reveal the performers once more "exactly as the painting pictures the conference," as one reviewer later wrote ("Progress").

23 After an intermission, "Sixty Years of Confederation," the pageant’s finale and most spectacular scene began.9 All of the standards of the various participating chapters of the IODE were carried in by white-clad standard-bearers who stood upstage to create a formal backdrop ("Progress"). Whereas the first eight scenes in the pageant interpreted life in Canada up to and including Confederation, this final scene presented the audience with a procession of Canada’s natural resources and products, as well as technical, cultural, and legislative advances since Confederation, each depicted by members of several IODE chapters parading across the stage in "symbolical costumes" designed by Sternberg (Historical Pageant 99). Young women representing the Dominion’s military forces "danced prettily" before ushering in the evening’s patriotic finale—the appearance of a woman dressed as the personification of Canada followed by another woman in the role of Britannia ("People"). As the curtain lowered, Canada stood beside Britannia.

Positioning IODE Ideology in Relation to Liberal Imperialism

24 Historical Pageant was typical of the pageant genre in that portrayals of the past in historical pageants were often prescriptive. In his study of historical pageants in the United States, David Glassberg suggests that the pedagogical imperative of Progressive Era American pageants was largely predicated on the theory that "history could be made into a dramatic public ritual through which the residents of a town, by acting out the right version of their past, could bring about some kind of future social and political transformation" (4).10

25 As in the United States, late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century historical pageants in Canada also provided ideologically loaded and didactic directives for participants and audiences. During the 1908 tercentenary of the founding of Quebec, for example, Sir Albert Henry George Grey, the 4th Earl Grey and the Governor General of Canada, wanted to use the occasion to strengthen bonds between the Dominion and Britain, and to persuade French Canadians to rethink their rejection of British imperialism (Nelles 319).

26 Unlike the 1908 pageant, the politics underpinning Historical Pageant embraced both domestic and imperialist loyalties and, as such, reflected the IODE position in 1927. Founded in 1900 by Scottish-born Montrealer Margaret Clark Murray as a way to mobilize Canadian women to aid Britain during the Second Boer War (1899-1902), the IODE—originally called the Federation of British Daughters of the Empire—advocated an allegiance to civic service and national patriotism while promoting the British Empire (Buckner 190). As a result, the organization was a mix of maternal feminism, in which women’s perceived innate nurturing could be harnessed for good deeds in the public sphere, and a twinning of national and imperialist patriotism that believed the best path for Canada was to maintain and strengthen its historical ties with Britain. Or, as articulated in the IODE’s "Aims and Objects of the Order," which was reproduced in the program of Historical Pageant, members were to pledge their commitment "To stimulate and give expression to the sentiment of patriotism which binds the women and children of the Empire around the throne and person of their Gracious and Beloved Sovereign" (Historical Pageant 5).

27 Canada’s relationship to the British Empire, however, was a matter of debate in 1927 among IODE members. The organization did not automatically defer to its British counterparts, such as the Victoria League, but instead exercised autonomy (Bush 88, 100-101). Indeed, the Echoes article "Recommendations for Celebration of the Jubilee of Confederation," urged IODE chapters to remember that "[t]he National aspect of our work as an Order needs to be more universally stressed and we should all conform to a National expression in the celebration of our National unity" (23). Similarly, as reported in the October 1926 issue of Echoes, at the IODE’s annual meeting that year, Miss R.M. Church, the National President of the organization, "reminded the members of the Jubilee of Confederation to be held in 1927. This she declared would be an opportunity for the members of the Order to demonstrate that they were true Canadians as well as Imperialists" ("Report of the Annual"). Yet, in the same report, it was noted that Miss Joan Arnoldi, the First National Vice-President of the IODE, had told the delegates "Canadians were receivers and not givers, and asked what we brought to the mother country compared to the advantages that were ours under the British Crown" ("Report of the Annual" 16).

28 This debate within the IODE was arguably a reaction to the liminality of Canada’s political and legislative landscape in 1927. Canada’s participation in WWI contributed to a growing national pride and was a factor in the dissipation of support for an imperial federation. Moreover, the Balfour Declaration, the outcome of the Imperial Conference in 1926, was the realization of this rethinking through the recognition of the increased autonomy for the British dominions:

28 Law would follow to secure sentiment when the British Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster in 1931.

29 Yet, the shift from colony to nation was neither simplistic nor homogenously embraced; it did not signal the end of allegiance to the British Empire for many English-speaking Canadians. Instead, during the 1920s there were numerous political leaders, social commentators, and citizens who subscribed to a "liberal imperialism" (a phrase coined by John W. Dafoe), which espoused the compatibility of a prosperous and essentially sovereign Canada existing within and at the service of a vigorous, though decentralized, British Empire (Buckner 187). After all, Canada and Britain continued to be linked through shared history, cultural and political institutions, and parliamentary practices (Berger 38-39).11 While allegiance to the British crown during this time was still assumed, the Balfour Declaration unequivocally stated that "Every self-governing member of the Empire is now the master of its destiny" ("Report of the Inter-Imperial" 14). The Prime Minister of Canada, William Lyon Mackenzie King, encapsulated this duality of thinking in expressing his pleasure with the Balfour Declaration. He claimed that his vitriolic grandfather, William Lyon Mackenzie—one of the leaders of the 1837 Upper Canada Rebellion and an advocate for Canadians having the same rights as British subjects in the motherland—would have been delighted by Canada’s increased self-rule. At the same time, however, King wholeheartedly envisioned Canada as "the Britain of the West" (Bothwell 321).

30 It was not long before the arts became a conduit for political commentary about the status of the Dominion. Near the end May 1927, for instance, just one month prior to the premiere of Historical Pageant, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) hosted its first CPR Festival. With multiple festivals to follow each year in cities across the country, the CPR Festivals were a brilliant marketing campaign initiated by John Murray Gibbon, the company’s publicity manager. In addition to selling train tickets, the Festivals were intended to celebrate Canada’s cultural diversity by featuring the music, dances, and traditional crafts of the various ethnic groups that comprised what Gibbon later coined as the "Canadian mosaic."12 Yet, for Gibbon, who programmed the festivals, Canadian nationalism was spoken with a British accent. In the CPR Festivals, nationalist pride in Canada was not seen to preclude allegiance to the British Empire, and British culture was always given a privileged place of honour (Lazarevich 12).

31 Historical Pageant was certainly not the first theatrical production written by a Canadian woman to reify governing ideology.13 As Kym Bird has noted, late nineteenth-century writer Sarah Anne Curzon was a supporter of Imperial Federation, a movement that had begun in the late nineteenth century with the goal "to gain imperial unity through forging closer economic and military ties to the British Empire and acquiring influence over imperial policy" (22). Similarly, Beverly Boutilier has argued that "[i]t was Curzon’s fervent hope that Canadians of her own time would recognize their indebtedness to these early patriots by working to promote the political destiny of Canadians as ‘Britons’" (60). By the late 1920s, the emphasis in Canada’s relationship to Britain had shifted a little closer to one of partnership. Nevertheless, pride in Canadian history is present in the plays of Curzon and, just as Historical Pageant provides access to the type of views in currency in 1927, Curzon’s plays such as The Sweet Girl Graduate (1882) and Laura Secord, The Heroine of 1812 (1887) reflect the political and gender concerns of their own period.

Using Female Characters to Convey IODE Ideology

32 In promoting the political status quo, one dramaturgical strategy employed by Edith Lelean Groves, another female playwright predecessor to Sternberg, was to use allegorical characters that personified values and places. Canadian audiences had had previous opportunities to see the Dominion cast as a female character and embodied on stage. During World War I, for instance, Groves had written several patriot plays and pageants for children, such as The Making of Canada’s Flag (1916), Saluting the Canadian Flag (1917), and Canada Calls (1918), which featured the allegorical characters, often calling for women to portray Canada and Britannia. (On occasion the allegorical personifications of Canada were male, though in Groves’s The Wooing of Miss Canada [1917], which celebrated fifty years of Confederation, there was also a female allegorical character because the plot involved Miss Canada finding happiness and protection in the arms of Jack Canuck.)

33 Sternberg’s choreography for the 1915 pageant Fantastic Extravaganza demonstrated that she was conversant in the conventions of the genre, particularly the use of allegorical characters as a means to convey a political stance. The culminating section of Fantastic Extravaganza, "War," asserted Canada’s loyalty to the British Empire by featuring a procession of dancers dressed as soldiers, sailors, and a messenger of peace. The appearance of Britannia and the colonies preceded several of Sternberg’s students dressed as Canada’s industrial products and the arts, as if visually pledging Canada’s manufacturing and cultural resources to the war effort and, in so doing, implicitly reiterating support for Canada’s place within the British Empire.

34 In a sense, Fantastic Extravaganza was a rehearsal for Historical Pageant, though this latter production was arguably more ambiguous in its positioning of Canada in relation to the British Empire. The allegory of Canada’s resource affluence was transposed from Fantastic Extravaganza to Historical Pageant’s finale, "Sixty Years of Confederation," which began with a procession of allegorical characters portrayed by several IODE Chapters. The provinces were represented by natural resources and followed by Dairy Maids, Fruit Pickers, and Miners. These were followed by IODE members portraying Telephones, Electricity, Art, Literature, Legislation, Mother’s Allowance, Workman’s Compensation Act, Soldiers’ Civil Re-Establishment, the Air Force, the Mounted Police, the Navy, and the Army.14

35 These images invoked pro-Canadian propaganda, but it was a pride in Canada that was clearly situated within the larger context of the British Empire. The image of imperialist allegiance would have been unavoidable for most audience members during the "Sixty Years of Confederation" section of Historical Pageant, when Mrs. Vera McLean Somerville, the woman cast as "Canada," mounted a dais draped with the Union Jack and sang O Canada, in an arrangement by Violet E. Clarke, a member of the William Lyon Mackenzie Chapter of the IODE ("Gowns"; "Progress"; and "IODE will Present").15 After Clarke finished, soprano Miss Agnes Adie, made her grand entrance as "Britannia" ("Gowns"). Holding a trident to show Britain’s sovereignty over the seas, she roused the audience with what one reviewer proclaimed, the "climactic thrill" of the evening with her rendition of Rule, Britannia ("Progress"). As the curtain descended on the final tableau, Canada and Britannia stood shoulder-to-shoulder under an Arch of Confederation ("Toronto").

36 It is unclear whether this final image was intended to signal that Canada’s place was beside Britain, or that Canada and Britain were equals, or possibly and even probably to convey both messages at once. What is clear, however, is that although it is possible to interpret Historical Pageant as less of a vote for parity between Canada and Britain than a pragmatic compromise and clarion call that Confederation and dominion status should not mean the end of Empire, national pride in Canada’s resources, legislative and cultural accomplishments was certainly celebrated. Furthermore, to at least one reviewer who attended Sternberg’s production, Historical Pageant presented the option of a conciliatory partnership between nationalist ambitions and imperialist allegiance as the way to proceed as a dominion, writing that Historical Pageant advanced "the sentiment deftly introduced at intervals of loyalty to Canada within the Empire" ("People"). Indeed, dramaturgically, Historical Pageant repeatedly saluted the accomplishments of Canadians while simultaneously revivifying Canadian support for the continuance and prosperity of the British Empire. Moreover, in her program notes, Sternberg wrote that she was interested not only in maintaining "the spirit of entertainment in its higher sense, which should be [theatre’s] role and its only raison d’être," but also in creating a production that "would mark a distinct advance in the placing of the stage at the service of the people for national weal" (Historical Pageant 17).

37 The use of allegory in Sternberg’s pageant, and in the pageant genre more generally, accomplished several theatrical and political goals. Allegorical characterization was less demanding of performers’ skills and therefore advantageous for large-scale productions involving a multitude of non-professional performers. It might be difficult to imagine how Mother’s Allowance or the Workman’s Compensation Act were actually represented onstage, but the visual impact invited a reading that the IODE supported the view that living under the aegis of the British Empire had facilitated Canadian prosperity. More importantly, the inclusion of women in allegorical roles in Historical Pageant and, in particular, the act of assigning IODE members—many married and middle-aged—to personify the Dominion and Britain, materialized the notion of "motherland," as if asking viewers to respond to the concept of patriotism with the same loyalty and visceral attachment usually reserved for maternal bonds. As Sternberg’s pageant illustrated, message, not subtlety, took centre stage.

38 In short, the concept of imperialism promoted in Historical Pageant did not preclude support for Canadian nationalism; Historical Pageant was not co-opting the occasion of the Diamond Jubilee, but rather artistically reifying a contemporaneous and operative political position that national sovereignty and Empire were compatible.

39 Political authority was—and is—not just a matter of legislation and law enforcement. As Lynn Hunt as argued, "Governing cannot take place without stories, signs, and symbols that convey and reaffirm the legitimacy of governing in thousands of unspoken ways" (54). Thus, Sternberg’s theatrical procession of female performers wearing symbolic costumes was not simply quaint and (now) antiquated fun, but the physical donning of political allegiance—a public display through which the women of the IODE—encouraged the equation of applause with ideological acquiescence.

40 The implications of abstracting and co-opting of women’s bodies on which to project political ideology—even IODE ideology—does not seem to have occurred to Sternberg. As David Glassberg has noted, American guidebooks for pageant planning that had been in circulation since the early twentieth century frequently encouraged the use of allegorical characters and symbolic tableaux vivants as a means to materialize virtues and nations (though the allegorical uses of women extends back beyond historical pageants) (18). As a result, "[s]uch tableaux offered women, who generally were excluded from the line of march, their major opportunity to appear in public celebrations, seen but not heard as they adorned floats pulled by their fathers, husbands, sons, and brothers" (18). In addressing the allegorical representations of women in published materials such as Simpson’s Confederation Jubilee Series, 1867-1927, Jane Nicholas states, "Men were idealized and constructed, but based on elements that could be connected to lived historical experiences. Women, however, were often allegorical figures representing space as well as national and imperial connections" (269). Likewise, in his discussion of the festivities planned to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee across the country, Robert Cupido suggests that the members of the national Pageants Subcommittee did not really recognize or attempt to incorporate women’s contributions to contemporary life into their directives. Instead, they recommended simply featuring women in allegorical roles (176).

41 While all these readings are insightful and helpful, they articulate late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century perspectives. Instead, it is possible that in 1927 Sternberg and the IODE felt that the allegorical use of women to embody virtues or political entities was an important way to shore up patriotic sentiments and enforce women’s role—the IODE’s role—as society’s moral leaders.

42 In justifying the time and energy the IODE members invested in producing and performing Historical Pageant, a case could be made that Sternberg’s script facilitated the participating IODE chapters in collectively addressing several of the core directives outlined in their organization’s "Aims and Objects of the Order," including "To supply and foster a bond of union amongst the daughters and children of the Empire"; "to celebrate patriotic anniversaries"; and, of the utmost importance, the sixth goal:

42 The phrase "to draw women’s influence" requires further consideration. During a period so closely following female emancipation in Canada and in a political climate that would, just two months later, see the initiation of the Person’s Case, it is possible that some audience members expected an even more overt assertion of female agency performed on stage. Nevertheless, Sternberg’s choices of female characters subtly reinforced longstanding goals of the IODE and stressed that the values the IODE cherished had antecedents in Canadian history. The seventh tableau, for instance, was of Laura Secord, an iconic figure within Canadian history. By including a tableau of Secord warning Lieutenant James Fitzgibbon of the impending American attack, Sternberg used the War of 1812 as a stand-in for the IODE’s desire in 1927 to rally support for the British Empire. Sternberg underscored this image with a note in the program that when the Americans attempted to invade the British colonies to the north in 1812, "the Canadas reaffirmed once more their stand for British institutions and backed this decision by the offer of their lives" (Historical Pageant 75). Similarly, although Madeleine de Verchères was not a British subject, her bravery in saving her home against "foreign" invaders could be read as emblematically championing the power women wielded in the private sphere just as the inclusion of the Ursuline nuns, who came to New France in 1639 to provide a Catholic education to native and French children as depicted in the fourth tableau, underscored the influence women had on children during their formative years.16

43 It was as if the choices of these specific historical figures provided an index through which IODE members could convey guiding principles: be proud of Canada and loyal to the Empire, defend one’s home and homeland, and help shape the future generations. Laura Secord, Madeleine de Verchères, and the Ursuline nuns were role models—personifications of the IODE’s sense of duty, both to Canada and to the British Empire.

Female Leadership in the Service of IODE Ideology

44 If the historical female characters in Historical Pageant stressed the IODE’s connection to women from Canada’s past, the program available to audiences positioned the organization and its membership as modern female civic leaders—an image aligned with other IODE materials produced at the time. In the months preceding the Diamond Jubilee, for instance, Echoes, the IODE’s magazine, had included various stories related to Confederation and its aftermath (e.g. Church; Hammond; and Coupland). The image of women presented here was not nostalgic, but rather embraced the modern and emancipated woman. As one unnamed IODE writer argued, women in 1927 had progressed a great deal since 1867:

44 The writer credited the civic leadership role by organizations like the IODE for providing important opportunities for contemporary women:

44 During the interwar years, the IODE’s membership numbers dropped—the 1930s would see a low of twenty thousand in contrast from a WWI high of fifty thousand (Buckner 196-97)— so perhaps, with the dwindling membership of the IODE in mind, these words were written as a way to attract new members.

45 Publicity material for Historical Pageant can be read as similarly functioning as an advertisement and membership drive for the IODE by depicting the organization as a modern and vital entity. That is, to a large degree, Sternberg and the IODE used the production to script a positive image for the organization and, thus, the political views and values that the IODE promoted.

46 Certainly, the centrality of the IODE would have been difficult for Historical Pageant’s audiences to miss. Reminders that the pageant was an IODE production were omnipresent. The first pages of the program distributed to audience members, for instance, contained a photograph and biography of the organization’s founder, Margaret Polson Murray. The program also included photographs of Mrs. R.M. Church, the National President, as well as photographs of the IODE’s regents. Several of the advertisers in the program, including the International Varnish Co. Ltd. and the Hygienic Hair Dressing Parlors, congratulated the IODE on the success of its pageant. Ad space purchased by a few of the IODE chapters as well as by the staff of the IODE official publication, Echoes, also appeared throughout the program. The charitable works of the IODE were represented in the program by a photograph of children in the care of a nurse at an IODE Preventorium. The official image of the IODE, as constructed by the program, promoted civic leadership by a well-organized association of outstanding women.

47 The very act of producing the pageant signalled that the IODE was an energetic organization, engaged in creative and social projects. Thus, while the organization’s agenda was serious and required dedication from its members, the message was that the IODE could fulfill its mandate through activities defined by communal "play": the IODE was a social, as well as political, entity.

48 The portrayal of the IODE as a convivial community of female civic leaders, however, was somewhat deceptive as it obscured the impulse to stratify society along race and class lines that was embedded in the foundation of the organization at the time. The massive numbers of participants and the civic-minded didacticism of pageants generally have led to a reading of the genre as community-oriented.17 While the same could be argued for Historical Pageant because of the large numbers of participants, the production was clearly dominated by the IODE, and, although the IODE theoretically welcomed "all women and children in the British Empire or foreign land who hold true allegiance to the British Crown," most members were from social positions of relative economic affluence and privilege that allowed its members time to participate in IODE activities such as Historical Pageant (Pickles 23, 24). In fact, the press reported that the intense preparations for Sternberg’s pageant had caused many IODE members to delay their yearly sojourns to their summer homes and trips to England ("Summer"). Moreover, membership in the IODE was, in practice, primarily initiated through invitation (Pickles 24), and access to Massey Hall, the venue for the production, was arguably limited to those who could have funds for leisure activities and who also might be already inclined to receive the IODE point of view. It is, therefore, possible to suggest that Historical Pageant actually unwittingly projected an exclusivity determined by the parameters of the IODE’s membership and served as a reminder that the concept of Empire was originally predicated on a belief in social hierarchies.

49 The exclusivity of the IODE was further affirmed by Historical Pageant’s patrons, and the production and its publicity implied that the politics advocated by the IODE was supported by the financial and social elite of both Canada and Britain. The weekly Saturday Night magazine issue immediately preceding the opening of Historical Pageant contained a notice enumerating the patrons of Sternberg’s production ("Patrons"). The list was a "who’s who" of polite society: His Royal Highness, The Duke of Connaught and Strathearn; Her Highness Princess Marie Louise; Their Excellencies, the Governor-General of Canada and the Viscountess Willingdon; His Honour the Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario and Mrs. William D. Ross; His Grace the Most Reverend Archbishop Neil McNeil; the Right Reverend Bishop Sweeny and Mrs. Sweeny; the Right Honourable Sir William Mulock, Chief Justice of Ontario; the Honourable G. Howard Ferguson, Prime Minister [Premier] of Ontario and Mrs. Ferguson; and His Worship the Mayor of Toronto, Sir Joseph Flavelle and Lady Flavelle. Mrs. Timothy [Margaret] Eaton. The list continued.

50 The patrons of Historical Pageant reveal a great deal about how the IODE publicly positioned itself. As if to validate the importance and quality of the pageant by promoting that it was supported by the upper echelon, patronage became a marketing tool—a calling card to attract the attention of the media. It also implied that in 1927 the IODE and the values it represented had enough cachet to attract the support of financial and social elites in Canada and Britain—that the IODE had access to the socially ascendant and politically powerful in both places and, thus, by association, assumed those attributes for itself. The exclusivity of the IODE’s membership and its published list of patrons further implied that whether or not the British political presence in governing Canada was in retreat, its influence in creating an implicitly vertical social hierarchy with British royalty at the apex was still securely fastened into the minds of many Canadians, even during a nationalistic event like the Diamond Jubilee.

Conclusion

51 According to the press accounts, the Historical Pageant was a success. The production was praised in Echoes for depicting the history of Canada with "dramatic vividness" ("Ontario"). As one newspaper observer noted, "judging by the line-up yesterday at the box office, the idea of the historic spectacle seems to have captured public fancy" ("IODE Will Present"). Another reviewer was impressed by "the applause of the large audience which braved the heat wave" ("People"). Yet, the accolades, media attention, and the appreciative audiences are not the only reasons why Historical Pageant should be remembered. The production was the last theatrical hurrah for Sternberg, whose mental and physical health had been in decline since her mother’s death in 1925 (Hehner). Her family had been so concerned about her depressed state that they had persuaded her to take an extended tour of Europe during the summer of 1926. After this hiatus, Sternberg began to accept student registrations for the 1926-1927 season; however, her continued dejection necessitated that her sister Sarah return to the studio to teach. These events also point to the likelihood that Sternberg had been in the throes of depression while she worked on Historical Pageant. Further, the stock market crash and economic tailspin of 1929, compounded by the deterioration in Sternberg’s health, resulted in the closure of the Sternberg Studio of Dancing. It was a harsh end to a veritable Toronto cultural institution—one of the few small business enterprises in the city run solely by a woman, who became a local legend for her large yearly school recitals that packed Massey Hall, for her "mammoth" interdisciplinary productions at the CNE Grandstand Shows, for the "spectacular rhythmics" of her choreography of "mass dancing" in Fantastic Extravaganza, and for her most ambitious and successful production, Historical Pageant ("Amy Sternberg"; "Dance"; and Tilley). After she died in the summer of 1935, while a patient in a hospital for the mentally ill, Sternberg was eulogized in the press as "one of Toronto’s memorable geniuses" (Hehner; and "Amy Sternberg").

52 Looking back it is possible to see that Sternberg’s private pain and the slow dissolution of her school were not the only fissures concealed by the celebratory tone of Historical Pageant. Although liberal imperialism was well subscribed in 1927, the "British Empire" was slowly being replaced with the "British Commonwealth of Nations"—a phrase found in the Balfour Declaration and a concept that reflected a transition away from past colonial relationships. The strong support for Britain during World War II, for example, did not prevent the swelling of nationalism in Canada during and after the War. The passing of the Citizen’s Act of 1947 meant that Canadian nationals were no longer British subjects. Two years later the Supreme Court of Canada became the final legal authority in the country when the possibility of appealing Canadian decisions to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London was terminated. In 1948, Canadians elected Louis St. Laurent, a vocally anti-imperialist Prime Minister. Vincent Massey became the first Canadian-born Governor General in 1952. Throughout this period, Canadian nationalism did not fully negate loyalty to the British Empire—after all, Massey’s sense of Canadian culture was largely attuned to British models—but by the 1960s, the denunciation of the kind of dual loyalties embraced by the Sternberg and many of her colleagues in the IODE was largely complete.18

53 Scholarly studies of how Canadians have rejected their colonial past are arguably more in vogue than examinations of Canadian allegiance to the British Empire. Yet, we should not ignore early twentieth-century Canadian supporters of liberal imperialism whose motivations and strategies offer insight into how social positions are produced and perpetuated. In this light, Historical Pageant serves as a reminder that, in 1927, the idea to stage IODE ideology could be entertained and entertaining.