Articles

The Murmuring-In-Between:

Eco-centric Politics in The Girl Who Swam Forever1

Nelson GrayUniversity of Victoria

Abstract

Viewing one of Clements’s earliest plays through an eco-critical lens reveals how this playwright manages to situate her post-colonial politics within a vision of the world that is unequivocally eco-centric. After detailing how Clements incorporated three primary sources in the conception and development of The Girl Who Swam Forever, this paper (employing Tim Ingold, Christopher Manes, Val Plumwood, Akira Lippit, Thomas King, and Jeanette Armstrong ) shows how the animist assumptions that inform the play’s action are fundamentally distinct from conventional Western ways of seeing. The paper then concludes by arguing that it is precisely this animist sensibility that provides Clements’s female protagonist with what Deleuze and Guattari have called "a line of escape" from the repressive constraints of human-centred thought, enabling her to imagine a world beyond the racist one that threatens to undermine her agency, well-being and self-respect.Résumé

Lorsqu’on examine l’une des premières pièces de Clements en adoptant une perspective écocritique, on voit à quel point cette dramaturge a réussi à inscrire ses politiques postcoloniales à l’intérieur d’une vision du monde qui est catégoriquement écocentrique. Après avoir décrit en détail comment Clements fusionne trois sources primaires dans la conception et le développement de The Girl Who Swam Forever, cette étude démontre (en s’appuyant sur des écrits de Tim Ingold, Christopher Manes, Val Plumwood, Akira Lippit, Thomas King et Jeanette Armstrong) comment les hypothèses animistes qui informent l’action de la pièce diffèrent fondamentalement des façons conventionnelles de voir les choses en Occident. L’étude fait valoir que c’est cette sensibilité animiste, justement, qui donne à la protagoniste de Clements ce que Deleuze et Guattari ont appelé «.une ligne de fuite.» pour échapper aux contraintes répressives de la pensée centrée sur l’être humain, lui permettant d’imaginer un monde situé au-delà de l’univers raciste qui menace sa fonction d’agent, son bien-être et son estime de soi.1 One of our most distinctive characteristics as humans has to do with our ability to imagine ourselves as other selves. Not only do we clothe our bodies, quite literally, in otherness—wearing the skins of animals and fabrics garnered from other life forms—but, as theatre artists are well aware, we engage as well in acts of imagination, enacting, as it were, the subjectivity of other beings. In the predominately human-centred tradition of Western theatre, actors primarily take on the roles of other human beings. The plays of Marie Clements, however, might be considered within another tradition—a more eco-centric one—in which actors give voice to other agencies, assuming the roles of diverse species, elemental forces, and hybrid, inter-subjective beings, comprised of both human and nonhuman selves.2 Eco-critical commentary on the nonhuman and hybrid characters in Clements’s work has yet to materialize—the result, perhaps, of concerns that the very mention of nature and ecology in the writings of a Metis3 artist like Clements might perpetuate colonial stereotypes of the "noble savage" or raise the spectre, characterized by Shepard Krech, of one of their offshoots: "the Ecological Indian." I would argue, however, that to ignore such nonhuman agencies is to perpetuate another kind of colonialism, one based on anthropocentric assumptions endemic in Western thought. For instance, an eco-critical reading of The Girl Who Swam Forever4 —one of Clements’s earliest plays—can show how this playwright draws on an entirely different set of assumptions to situate her post-colonial politics within a vision of self and world that is unequivocally eco-centric.

2 Based on plot alone, The Girl Who Swam Forever might easily be mistaken as psychological realism. Its literal action depicts the story of Forever, an orphaned First Nations girl in the 1960s, who—after a brief liaison with a non-native fisherman—discovers she is pregnant.5 Battling a guilty conscience, Forever runs away from residential school and seeks shelter in an abandoned fish boat. Here, plagued by nightmarish visions, she becomes increasingly desperate: first, because of her young fisherman/ lover’s fearful suspicions that she might indeed be pregnant; and, second, because of an overly-protective elder brother who is angry and humiliated that the father of her infant-to-be is non-native.

3 During the conception of this play, however, Clements drew on three primary sources in a way that leads away from the conventions of Western realism. One of these was Wayne Suttles’s Katzie Ethnographic Notes, a book that includes two memoirs—one by Wayne Suttles, the other by Diamond Jenness—detailing the traditional beliefs and practices of the Katzies, a First Nations people whose pre-contact territories included what is now known as British Columbia’s Pitt Lake region. Jenness’s memoir derives entirely from his interviews with "Old Pierre," a "medicine man" with a thorough knowledge of Katzie oral history, and it is one of the stories from this history that Clements cites, in quotation marks, at the beginning of her play:The Katzie descended from the first people God created on Pitt Lake. The ruler was known as Clothed with Power. This first chief had a son and a daughter. The daughter spent her days swimming and transformed into a sturgeon. The first to inhabit the Pitt Lake. It was from this girl that all sturgeon descended [...]. (51)While Clements was drawing on the stories of Old Pierre, however, she was influenced by a second source: namely, a series of disturbing media reports about sturgeons beaching themselves on the banks of the river, literally drowning themselves in the air. As she put it, "it was as if these sturgeons were trying to tell me something" (Interview). Moreover, around this same time, another BC writer—Terry Glavin—published A Ghost in the Water, a book that also pays attention to the sturgeons of the Pitt Lake region. Glavin’s book cites a series of unexplained sturgeon deaths similar to those that had drawn Clements’s attention, but it does more, as well, providing an historical account of the near extinction of the sturgeon in the early twentieth century and detailing the fundamental relationship between these remarkable creatures, who have been around since prehistoric times, and the Katzie people, who have lived by the lake and fished it since time immemorial.

4 Clements incorporated all three of these sources to create a scenario in which Forever undergoes a dream-like underwater transformation and encounters her grandmother’s spirit in the form of a hundred-year-old sturgeon lying buried in the thick mud of a polluted river.6 This shape-shifting experience proves a major turning point in the action, renewing Forever’s belief in herself, so that when she regains her human form, her resolve to live is strengthened and affirmed. Forever’s self-realization and survival, in other words, is accomplished via a shape-shifting experience through which she makes connections between the traditional beliefs of her people—beliefs "buried" and denigrated by colonizing populations—and the life-giving nourishment and energies of the sturgeon, a species threatened with extinction due to the greed and pollution of these same colonizers. Clements’s ability to depict this—making links between Forever’s agency as a Katzie woman and that of the sturgeon—ensures that the action of her play is both political and eco-centric: in effect, a post-colonial politics enfolded in an eco-centric vision.7

5 As Mary Midgley has pointed out, the awareness and perceptual worlds of the other life forms with which we co-exist on this planet will always, in some ways, exceed our understanding.8 Yet to argue that Clements disregards this notion and that The Girl Who Swam Forever appropriates the autonomous agency of the Pitt Lake sturgeons to explore an essentially human-based conflict would not only be eliding the particular worldview that this play depicts, but also making assumptions about culture and nature that—while germane, in many respects, to Western ways of seeing—are problematic when viewed in an eco-critical context. In Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, for instance, Val Plumwood shows how a history of Christianity and rationalist philosophy in the West has promoted assumptions about culture and nature as binary opposites that shore up a privileged (and patriarchal) view of "human" as a species removed from and superior to other forms of life. Lynn White Jr., David Abram, Christopher Manes, and Akira Lippit have all made supplementary arguments, pointing out the dangers of Western assumptions about self and world in an age of eco-crisis. Akira Lippit, in his book The Electric Animal, shows how, with few exceptions, Western philosophers from Aristotle to Heidegger have defined the essence of "human" as the negation of what it means to be an animal. "The effort to define the human being," Lippit writes, "has usually required a preliminary gesture of exclusion: a rhetorical animal sacrifice. The presence of the animals must first be extinguished for the human being to appear" (8).

6 In contrast to these notions of "human" as the negation of animal or as a species that comes into being by mastering or overcoming "the animal within," many animist cultures understand human identity as that which can only come into being through a dialogical relationship with nonhuman nature (Ingold 114). Jenness, for instance, describes Old Pierre’s accounts of Katzie puberty initiations in which the youths of the tribe, as a crucial part of becoming an adult, must acknowledge their personal connections to the vitality or "spirit power" of some nonhuman creature or force of nature. In other words, according to Katzie traditional practice, it is only by becoming other-than-human that one can become authentically "human" (qtd. in Suttles 41-64).

7 The idea of becoming a social being by taking on the vitality of an animal or of some elemental force may seem peculiar to the Western mind, but it makes complete sense from an animist perspective that, according to Graham Harvey, views the world as comprised "of persons, only some of whom are human" (Harvey xi). Moreover, as Harvey and others have taken pains to point out, this animist perspective has some obvious ecological implications (179-186; Manes 339-50; White 1204-07). The anthropologist Tim Ingold, for instance, observes that when humans "are brought into existence as organisms-persons within a world that is inhabited by beings of manifold kinds," the relationships "which we are accustomed to calling ‘social’ [become] but a subset of ecological relations" (5).

8 In The Girl Who Swam Forever, as in all of her plays, Clements ushers in this animist sensibility at the very outset

of the action. Here, by opening with Old Pierre’s genesis story, she situates her coming-of-age story in a realm where social relations are ecological ones, and she continues to underscore this by establishing direct links between the traditional narrative and the actions of her protagonist. Such links are unequivocal, for instance, in the scene where Forever and her brother are "dreaming" to the bottom of the river to meet with the spirit of their grandmother, and the latter, as The Old One, relates a second version of the Katzie story:THE OLD ONE. The Lord above gave my forefather a wife by whom he had two offsprings, a son and daughter. These children never ate food, but spent all their days in the water—(FOREVER and BROTHER BIG EYES begin to move in slow motion, as if through water.)

F/BBE. I remember the river.

THE OLD ONE. "My friends," he said, "you know that my daughter spends all her days in the water. For the benefit of generations to come, I have decided she shall remain there forever."

BRO. B. EYES. Forever?

THE OLD ONE. He led her to the water’s edge and said, "My daughter, you are enamored of the water. For the benefit for generations to come. I shall now change you into a sturgeon." (FOREVER begins to transform and move like a sturgeon, the image of a sturgeon appears on her as she moves.) (63-64)

As Thomas King has so eloquently observed, "The magic of Native literature—as with other literatures—is not in the themes of the stories—identity, isolation, loss, ceremony, community, maturation, home—it is in the way meaning is refracted by cosmology, the way understanding is shaped by cultural paradigm" (Truth 112). To fully appreciate how this occurs in The Girl Who Swam Forever means delving into animist ideas of transformation and inter-subjectivity that inform the conflict and resolution in this play. These two structural ideas, however, which ultimately give rise to modes of perception, are so interwoven in Clements’s writing that to speak about one inevitably means touching on the other.

9 The central conflict in The Girl Who Swam Forever involves Forever’s physical transformation, since, if the fetus that is developing in her womb is brought to term, the child that will be born will be perceived as an individual from two divided cultures. Implicit in this, then, is the inter-subjectivity of this First Nations woman, the idea that she is by no means an isolated entity, but is rather an embodiment of natural and cultural forces in a state of becoming that has, due to racist fears about miscegenation, reached an impasse. From a Western humanist-feminist perspective, to speak about Forever in this way might appear to reduce her agency as an individual, yet this very idea of individuality, along with the kind of conflict it anticipates, is at odds with animist thinking.

10 In the West the idea of conflicted subjectivity has been influenced by Freud’s theories of an internal division of the self, comprised of a struggle between id, ego, and superego that must, for the health of the individual, be brought into balance. The inter-subjectivity implicit in animist cultures, however, has more in common with ecological ideas of interrelationships, placing emphasis on the individual’s responsibility in terms of the human and nonhuman environment in which that individual resides. The First Nations novelist and poet Jeannette Armstrong, for instance, speaks about the "four selves" that, in the indigenous Okanagan language, are each inherently linked to relationships with family, with a larger human community, with the land, and with the ancient, ongoing life of the Earth (319-324). Thomas King refers to a similar notion of identity in his discussion of "All my relations"—"the English equivalent of a phrase familiar to most Native peoples in North America." "All my relations," he writes, "is at first a reminder of who we are and of our relationship with both our family and our relatives. It also reminds us of the extended relationship we share with all human beings" (Relations ix). As King goes on to explain, however, "the relationships that Native people see go further, the web of kinship extending to the animals, to the birds, to the fish, to the plants, to all the animate and inanimate forms that can be seen or imagined" (Relations ix). From this cultural perspective, then, subjectivity is neither singular nor divided internally, but exists as a plurality in a world of reciprocal inter-relationships, and, because these inter-relationships involve both humans and nonhumans, subjectivity is less ego-centric and more particularly eco-centric—less concerned, that is, with individual striving than with how one acts as part of an interdependent web of relations. Accordingly, in Clements’s play, when Forever is in such despair that she no longer sees the point of living, the stage directions call for an image of a sturgeon to be projected onto her body (68). Similarly, when the grandmother spirit comes to Forever’s aid, she places her hand on her granddaughter’s stomach, and speaks about the continuation, within her, of an entire cosmos:Here. Here. These pieces, these stories have found a place in you. Found a place to grow from the beginning and circle to include everything that is you and circle to include everything that is us. Here. Here. It circles and in this motion a million year old dream surfaces. (68)As Forever’s grandmother’s words suggest, notions of transformation and inter-subjectivity, which figure so prominently in the depiction of Forever’s conflicts, are equally instrumental in their resolution and in how the grandmother/Old One brings this about. At the beginning of the action, immediately after Clements cites the Katzie genesis story, "a voice speaks—large, dark and old," and a light "splashes down into the darkness" to reveal, on the bottom of the river, "the OLD ONE," rocking in a rocking chair. "Sometimes," she says, "you don’t know your own story from the bottom up, or from the top down, until it meets you."Meets in you. Words and silence, swimming and falling to the middle, circling each other in a dance of remembering. A remembering transforming. A dream from the here and now to the beginning, and again from the here and now to the beginning again. (52)As an opening to the play, this is mysterious-sounding language indeed—bound to "communicate," as T.S. Eliot observed about "genuine" poetry, "before it is understood" (238). But what does this communicate and how is it, eventually, to be understood? The script’s character description tells us that the OLD ONE is both the girl’s dead grandmother and "an ancient Sturgeon, Old, gentle, and deep" (51).

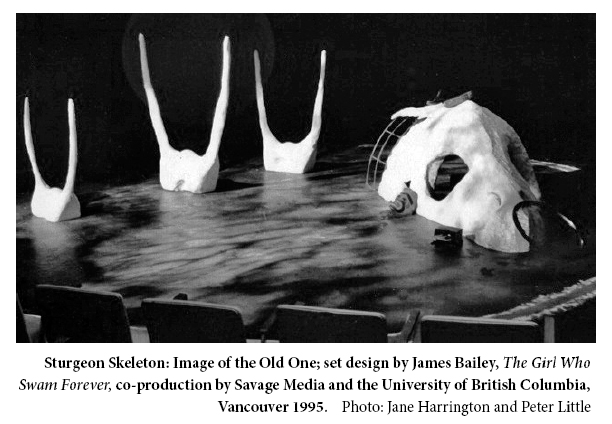

Sturgeon Skeleton: Image of the Old One; set design by James Bailey, The Girl Who Swam Forever, co-production by Savage Media and the University of British Columbia, Vancouver 1995.

Display large image of Figure 1

11 Sturgeons are old in a couple of ways. As a species, they antedate human history, and individual sturgeons live to be over a hundred years old, having the ability to exist for extended periods of time "in a state of suspended animation so pronounced that it is not unlike death" (Glavin 27). All the same, though, there is still a good deal of mystery in what the Old One is saying when she speaks about "[a] remembering transforming" and a "dream from the here and now to the beginning, and again from the here and now to the beginning again."

12 This mystery can be partly understood by keeping in mind the belief in re-incarnation that persists—despite the incursion of Christianity—in the ethos of many First Nations people (Mills). In Clements’s play, Forever’s internalization of this belief becomes readily apparent when, after escaping from residential school, she re-encounters her fisherman/lover and senses his fearful suspicions that she might be pregnant:FOREVER. He just stared at me. Quiet for a long time. So quiet he was almost begging me not to tell him so I just sat there and he just sat down. Me wishing he would say something and him wishing I wouldn’t say anything. So quiet I started listening to my insides. I could hear Grandmother’s voice inside me. Right inside my stomach with it. Listening, guggling [sic], bubbling through my veins. Not so much words but a song she used to sing to me when I was a kid and scared. Vibrating through my body like the heartbeat of a drum. He got quieter. I asked him if he could hear anything.

FOREVER. Can you hear anything?

JIM. No.

FOREVER. No? No ..... I wasn’t about to tell him about my Grandmother was there inside me too ..... he looked scared enough. (63)

By making it evident that Forever’s child-to-be is, in some sense, a re-incarnation, Clements sheds light on the pronouncements that the Old One makes at the beginning of the play, since, as a reincarnation, the child is a kind of "remembering transforming." In this play, however, the notion of transformation always carries the additional import of the nonhuman, and when, in the conclusion of the action, "the image and cry" of Forever’s child is brought forward, it is bracketed, immediately before, by "the carcass of a sturgeon [that] is strung up and cut open" and, immediately after, by the image of a leaping sturgeon (70).9 Such juxtapositions serve as reminders of the parallels established throughout the play between Forever’s actions and those of the sturgeon/girl in the Katzie story. If we read the metaphors of the play through the particular cultural paradigm that Clements invokes, however, the implication is that Forever’s child is but the latest incarnation of an ongoing transformation that began with the original genesis story. In this sense, then, the spirit of Forever’s grandmother is both an ancient 800-pound sturgeon and a voice that echoes all the way back to the first chief’s daughter, the one who discovered her agency in the shape of a fish and forged a connection between it and the Katzie people, and Forever, by "becoming sturgeon," has re-situated linear time in a synchronous field of relations, reincarnating and re-awakening an ancestral past that has long been silenced, and giving voice to it anew. Forever’s grandmother, speaking as the Old One again, conveys something like this in a monologue half way through the play:THE OLD ONE. A hundred years I have been talking but no one has listened. I weigh 800 pounds with words spoken but not heard. 800 pounds. I have grown 100 years to reach you but still nothing. Nothing until I heard my voice swimming inside you. I took those 800 pounds of silence and spun them in years of circles to create you. You are made of words in my silence. You are made of a silence that is me before everything. (61)

What emerges, then, both in this monologue and in the action of this play as a whole, is an animist view of existence, described by the anthropologist Tim Ingold as a perpetual process of becoming. In animism, he explains,no form is ever permanent; indeed the transience or ephemerality of form is necessary if the

current of life is to keep on flowing [...]. Borne along in the current, beings meet, merge and split apart again, each taking with them something of the other. Thus life, in the animic ontology, is not an emanation but a generation of being, in a world that is not pre-ordained but incipient, forever on the verge of the actual. (113)Ingold’s observations can help us to see that the Old One is, in effect, giving expression to this "animic" view of the world as an open-ended, ongoing transformation in which existence as it moves forward, continually folds back, re-informing the past and being revitalized by it.

13 What this discussion of animism has not touched on, though, is how Forever’s encounter with her grandmother/sturgeon resolves the racial tensions that are at the source of Forever’s initial dilemma. While it is easy enough to understand how Forever’s experience of her sturgeon self might affirm her own ancestral identity, how, one might ask, does it resolve Forever’s concerns that her child will owe its heritage to two apparently conflicting cultures?

14 To answer this final question, it is helpful to allude briefly to the philosophical discourse of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. In their writings on "Becoming Animal," Deleuze and Guattari propose an ontology that bears two significant similarities to Ingold’s descriptions of the animist one: first, like animism, it configures existence as an open-ended mode of becoming; and, second, it avoids anthropocentric assumptions by asserting that human beings can participate in this "becoming" through abandoning the notion of a fixed identity and entering into a reciprocal or dialogical relationship with what they call the "animal." "We believe," they write, "in the existence of very special becomings-animal traversing human beings and sweeping them away, affecting the animal no less than the human" (87). Furthermore, as in the animist transformations of the kind that Forever undergoes in Clements’s play, the "becomings-animal" to which Deleuze and Guattari refer provide a version of "human" that, like their own view of existence, is always in process. "A becoming," they write, "is always in the middle; one can only get it by the middle. A becoming is neither one nor two, nor the relation of the two; it is the in-between, the border or line of flight or descent running perpendicular to both" (94). For Deleuze and Guattari, understanding "human" as a continual state of "becoming" provides a way out of the restrictions assumed by essentialist and teleological thinking. Yet, in this same discourse, they take pains to point out that such "becomings-animal" are neither regressions nor identifications, nor are they a simple "return to nature," but, rather, that they offer "a line of escape" from such reductive ways of thinking, allowing for more heterogeneous relationships to take place. "To become animal," they write, "is to participate in movement, to stake out the path of escape in all its positivity, to cross a threshold, to reach a continuum of intensities that are valuable only in themselves" (96).

15 The transformation that Clements’s protagonist undergoes in The Girl Who Swam Forever is a similar "line of escape"— neither a regression nor an essentialist identification nor a simplistic return to nature—and one of the ways to illustrate this is with reference to another Katzie story, one that Clements specifically drew upon as a way to resolve her play. In this story, told by the elder Old Pierre and recorded by the ethnologist Diamond Jenness, a "half-breed Indian near Abbotsford" rather than acknowledging an animal, bird or "force of nature" as his "guardian spirit," claimed that the source of his vitality inhered in a locomotive (qtd. in Suttles 48). Jenness quickly adds that this particular "guardian spirit" was "abnormal," and that "the other Indians" initially laughed at the one who proposed it, but such disparagements, as the ethnologist goes on to explain, did not alter the man’s "abnormal" belief:He insisted, however, that it enabled him to control the weather, because a locomotive goes everywhere through rain and sunshine; and he said that because they had mocked him, he would make the weather very cold for two months. When snow fell the next day and the weather did remain cold for two months, the Indians believed him. (qtd. in Suttles 48)Early on in the action of The Girl Who Swam Forever, Clements employs the idea of this aberrant "guardian spirit," when a train comes storming through the town and Forever, longing to catch it, thinks "about an elder who wanted his spirit guardian to be a locomotive because it was so strong and made of steel" (54). At this point, Forever merely watches the train pass by, but the next time the train whistle sounds, it is after her shape-shifting experience, and this time she boards the train and heads off into the city. What Clements’s stage directions would have us understand, however, is that for Forever (as for the "abnormal" Katzie "half-breed") this train is an extension of the nonhuman vitality embodied by the sturgeon. "The train," Clements writes, "becomes a white sturgeon and a train, a white sturgeon and train, white sturgeon, train. Like it is dancing between the two" (69).

16 Like many of this playwright’s stage directions, the metaphorical complexity that this image proposes would be challenging to achieve in a stage production.10 To disregard it, however, would be a mistake, since what it underscores is, in effect, the idea that Forever’s "line of escape" will be to avoid the binary thinking that would define one race against another and that would conceive of nature and culture as opposites. Instead of an essentialist portrayal of a First Nations woman as inherently "natural," an identification that might relegate her to the misty forests and dusty plains of some long-lost wilderness era, what Clements is proposing here, in this affirmation of cross-cultural hybridity, is an image of something much more heterogeneous and open-ended, and at the end of the play, as the sturgeon/train enters the city, it is as if Forever’s underwater transformation, by demonstrating the possibility of a dialogic relationship between species, were now enabling her to conceive the possibilities for further transformations and dialogue, and, in particular, for those that might allow the very embodiment of the cultural heterogeneity that is swimming, fish-like, within her, to be born:FOREVER. (Voice-over) I am swimming Grandma. I am going to have this baby, this dream. Maybe it will have blue eyes and brown skin. Blue eyes so it won’t have to stare at us anymore because it would know us, because it would know itself. (70)

Forever’s voice-over—the last words to be uttered in the play— points the way to a culture free of racist attitudes and ways of thinking. However, by making nonhuman others central to the action in this play and by doing so in a way that consistently undermines the nature/culture binary, Clements is also able to extend the pluralist vision of post-colonial politics to portray an eco-centric worldview.

17 Engaging with the philosophical, cultural, and political underpinnings of this worldview moves the play a good deal, it seems to me, from the reductive stereotypes of the "noble savage" and "Ecological Indian," but it also makes it apparent that to read the sturgeons in this play as examples of the "pathetic fallacy" in any pejorative sense is to make ontological assumptions that are, in effect, anti-ecological. Such assumptions can hardly do justice to the kind of world that Clements is portraying here: one where human identity is not something fixed, closed, and set off from a world of others and other species that it seeks to repress and master, but, rather, something more fluid and permeable, to be discovered in an experience of inter-subjectivity. And in Clements’s depiction of this complex inter-subjective identity—of a Katzie girl and a Katzie ancestor who are also sturgeons, and of a child-to-be that is both native and non-native—there is room for multiple agencies, comprised of both human and other-than-human forms, and a voice that speaks of neither one nor the other, but of the murmuring-in-between.

Works Cited

Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Vintage, 1997.

Armstrong, Jeannette. "Keepers of the Earth." Ecopsychology. Ed. Theodore Roszak, Mary E. Gomes, and Allen D. Kanner. San Francisco: Sierra Club, 1995. 316-324.

Clements, Marie. The Girl Who Swam Forever. Footpaths and Bridges. Ed. Shirley A. Huston-Findley, and Rebecca Howard. Ann Arbour: U of Michigan P, 2008. 51-70.

— . Personal interview. 15 November 1995.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. "Becoming Animal." Animal Philosophy. Ed. Mathew Calarco, and Peter Atterton. London: Continuum, 2004.

Eliot, T.S. Selected Essays. London: Faber, 1932.

Freud, Sigmund. The Ego and The Id. Trans. Joan Riviere. New York: Norton, 1962.

Glavin, Terry. A Ghost in the Water. Vancouver: New Star, 1994.

Harvey, Graham. Animism. New York: Columbia UP, 2006.

Ingold, Tim. The Perception of the Environment. London: Routledge, 2000.

King, Thomas, ed. Introduction. All My Relations. By Thomas King. Toronto: McClelland, 1990. ix-xvi.

— . The Truth About Stories. Toronto: Anansi, 2003.

Krech, Shepard, III. The Ecological Indian. New York: Norton, 1999.

Lippit, Akira. Electric Animal. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2000.

Manes, Christopher. "Nature and silence." Environmental Ethics 14 (1992): 339-50.

Midgley, Mary. Beast and Man. London: Routledge, 2002.

Mills, Antonia, and Richard Slobodin, eds. AmerIndian Rebirth: Reincarnation Belief among North American Indians and Inuit. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1994.

Plumwood, Val. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. Opening Out. London: Routledge, 1993.

Suttles, Wayne. Katzie Ethnographic Notes. Ed. Wilson Duff. Victoria: British Columbia Provincial Museum, 1979.

White, Lynn, Jr. "The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis," Science 155 (1967): 1203-1207.

Notes