Articles

The. Women. The Subject(s) of The Unnatural and Accidental Women and Unnatural and Accidental

Erin WunkerDalhousie University

Abstract

This article has a methodological framework that uses post structural theories of the archive as well as performance theory to compare Marie Clements’s play The Unnatural and Accidental Women with Carl Bessai’s celluloid adaptation Unnatural and Accidental. The article opens with a claim that Clements’s play incites a radical recognition of the Other through a Derridan politics of "hauntology." The article then suggests that while Clements’s play leads the audience in a performative and ethical recognition of the Other, the celluloid adaptation destabilizes the radical politics of the play. The article closes with a consideration of what is lost in Bessai’s adaptation that cuts from its title the very subjects of Clements’s play: the women.Résumé

Cet article propose un cadre méthodologique qui s’appuie sur des théories poststructurelles de l’archive de même que sur la théorie du jeu, lesquelles sont appliquées à la pièce The Unnatural and Accidental Women de Marie Clements et à l’adaptation cinématographique Unnatural and Accidental de Carl Bessai. L’auteure avance d’abord que la pièce de Clements incite à une reconnaissance radicale de l’Autre par une politique derridienne de la «.hantologie.». Il poursuit en faisant valoir que, si la pièce de Clements mène son public vers une reconnaissance performative et éthique de l’Autre, l’adaptation cinématographique déstabilise la politique radicale mise de l’avant dans la pièce. L’article conclut par un examen de ce qui est perdu dans l’adaptation de Bessai, qui retranche de son titre le sujet même de la pièce de Clements.: les femmes."I see you—and don’t worry, you’re not white."

"I’m pretty sure I’m white. I’m English."

"White is blindness—it has nothing to do with the colour of your skin." (Clements, The Unnatural and Accidental Women 82)

1 What is the subject of our looking?1 Like Peggy Phelan, I, too believe that "what one can see is in every way related to what one can say" (Unmarked 2). The somatic bond between the image and the word is flexible, but in the case of bodies is it indivisible from flesh? In the case of the subjects of Marie Clements’s play The Unnatural and Accidental Women and its celluloid adaptation Unnatural and Accidental there is no easy answer. Phelan suggests that images dictate discourse and as "more and more images of the hitherto under-represented other" appear, contemporary culture manages to find increasingly inventive ways to "name, and thus to arrest and fix, the image of that other" (2). Yet, happily, contemporary culture fails to mask fully the image of the other. Representation over-communicates and can never quite pull off a totemic translation of the other. This site of excess meaning is, according to Phelan, supplemental (2). It does not fit into contemporary culture’s semiotic archive. But contemporary culture is an adaptable organism, and I am interested here in a specific case where a resistant text—the play—manages to escape totemic representation, but its adaptation—the film—is eventually arrested and translated into fixed, totemized, and expected modes of representation. In short, it is made subject to recognition.

2 I need to make clear what I mean by archive. Much has been written, of course, about the nature and practice of the archive, and I invoke both philosopher Jacques Derrida and performance scholar Diana Taylor when I speak of it here.2 I understand archive as a collection of memories, moments, and histories that have become collective factualized history through a process of selection and disposal.3 The archive—which becomes material and normalized through the connivance of what Althusser would have called Ideological State Apparatuses—is created and sustained by the referents of pronouns. Clements’s play works to destabilize the archive by creating lines of connections between the women that story and the stage. The central subject of my inquiry is to think through how and why this successful destabilization is co-opted back into the totemic patriarchal archive in its film adaptation.

3 The subjects of the play are predominantly the victims of Gilbert Paul Jordan. As both literal and figurative apparitions, they invite the viewer to witness their narratives and this potential witnessing upends any attempts to archive their deaths. Learning to speak with ghosts ruptures the stable image of the socio-cultural semiotic archive and subverts the linguistic hegemony that inscribes gender and regulates bodies. The translation of representation, from theory to practice, from monolithic archive to archive-destabilizing force, converses with Peggy Kamuf’s assertion thatto every stranger as well is extended, even before one begins to speak, the promise of the word’s repetition. The given word binding one to another does not even have to be given "in person" as we say. It binds me as well to all those I never encounter except by responding to an address tendered in mediation, through any kind of trace left to be represented by another. ("To Follow" 3)Clements’s play hinges on this question of care, creating a community of witnessing between the characters themselves and the audience as witnesses. As one reviewer puts it, "Clements [...] has managed to turn a true story of murder and tragedy from what is gruesome and despicable at best into a beautifully presented [...] play" (Hopkins 7). Predominantly populated with the murdered women, the play creates a tightly knit community where the murdered women come together to support Rebecca, the living half of the central dyad. The Unnatural and Accidental Women centers around Rebecca who is described as "mixed blood/Native—a writer searching for the end of a story" (n.pag). The play hinges around Rebecca’s search for her mother who "went for a walk twenty years ago and never came back" (13). It is her search that literally sets the stage for the murdered women to tell their stories. Importantly, in the original text, Rebecca’s decision to look for her mother is decidedly unsentimental and very much her own. Early on she reflects thatIf you sit long enough, maybe everything becomes clear. Maybe you can make sense of all the losses and find one thing you can hold on to. I’m sitting here thinking of everything that has passed, everyone that is gone, and hoping I can find her, my mother. Not because she is my first choice, but because she is my last choice and [...] my world has gone to shit. (13)Rebecca’s search for her mother is an attempt to travel back into memory, history, and time in order to meet a ghost. This ghost is an absent referent, whose violent translation into spectre is under erasure; she is both viscerally connected to her and separate from her quotidian existence. Like the Freudian unconscious that is never directly accessible, Rebecca’s absent mother has haunted her for two decades. The play is a narrativization not just of the murders, but also of Rebecca’s own loss and longing. I hesitate to suggest that the play is an analysis of a melancholic patient, but it bears some important similarities to Freud’s claim that the cure for melancholia is a literal storying of the self.4 The audience acts as witness to the stories and bears the ethical responsibility of recognition.

4 The film, however, whose title is changed to Unnatural and Accidental, fails to translate the stories and radical sense of community that are the fabric of the play. The Unnatural and Accidental Women—Unnatural and Accidental: What is lost with the removal of two words? The. Women. An article and the subject. In the remainder of this essay I compare Clements’s play with its Gemini Award-winning adaptation. In so doing I suggest that Clements’s radical feminist politics of community are recuperated back into the monolithic patriarchal archive.

5 Act One of The Unnatural and Accidental Women opens with a series of descriptions. Clements instructs that the "scenes involving the women should have a black and white picture feel [...] animated by the bleeding-in of colour as the scene and their imaginations unfold" (3). The monochromatic tones lend a documentary feel in stark contrast to the live bodies on stage. The women themselves are described in terms of not only their age and appearance, but also their personalities. Rose, the switchboard operator, has "a soft heart, but thorny," while Mavis is "a little slow from the butt down, but stubborn in life and memory" (n.pag). Clements’s women are personable, and the audience is invited to connect with them in the same moment it is reminded that these women are dead. Rather than describe the killer in terms of his own personal characteristics, he is, instead, described as "a manipulative embodiment of [the women’s] human need" (n.pag). Immediately any preconceived expectations are put off—the women, though decidedly victims of their status and situation are not powerless. The killer is not merely a racist misogynist but a fleshly manifestation of human emotion. Here Clements does what Ward Churchill calls the "negation of the negation" (107). By refusing to give Gilbert Paul Jordan agency, Clements refuses the impulse to characterize the women as victims of race, sex, and consequence. Moreover, the audience is unlikely to misrecognize or lose the subjects of the play.

6 The play opens with "a collage of trees whispering in the wind… the sound of a tree opening up to a split. A loud crack—a haunting gasp for the air that is suspended" (9). Across this soundscape the voice of a logger calls a warning in the same moment that Aunt Shadie calls for her daughter. "TIM-BER" is layered over "Re-becca" thereby aligning the two; Rebecca is both warned and warning, tree and daughter, while the tree is at once a looming threat, and a woman felled. Out of this sonic-image of descent "a big woman suddenly emerges from a bed of dark leaves. Gasping, she bolts upright, unfallen" (9). Aunt Shadie rises from the earth, which is simultaneously an image of herself in bed accompanied by the following slide: "Rita Louise James, 52, died November 10, 1978 with a 0.12 blood-alcohol reading. No coroner’s report issued" (9). Clements weaves the city with the forest, suggesting not simply that women are aligned with the earth, but rather that the viewers should correlate the felling of trees with the bodily violence of the women’s deaths.

7 A second slide is displayed and reads "TIMBER." As lights train in on Rebecca seated in her Kitsilano kitchen reading, writing, and drinking, Aunt Shadie and the logger continue walking and working. Rebecca considers the nature of nature:Everything here has been falling—a hundred years of trees have fallen from the sky’s grace. They laid on their backs trying to catch their breath as the loggers connected them to anything that could move… Hotels sprung up instead of trees—to make room for the loggers. First, young men sweating and working under the sky’s grace. They worked. They sweated. They fed their family for the Grace of God. And then the men began to fall. First, just pieces. (10-11)It is important to note here that while there is a palpable tension between the male loggers and the trees—they are later described as doomed lovers—both men and trees fall to a larger, unnamed hunger that consumes them both. The trees are uprooted from their natural habitats to be carved into homes for the loggers, who are also uprooted from their lives and live in camps while they work to sustain the logging industry. The trees and the loggers become locked together in a deadly embrace. "[Y]ou never knew what might be fallen," Rebecca muses. "A tree. A man. Or, a tree on its way down deciding to lay on its feller like a thick and humorous lover, saying....." "Honey," continues Aunt Shadie, "I love you—we are both in this together. This love till death do us part—just try and crawl out from under me" (11). The relationship between logger and trees is transposed, exposing what Cynthia Sugars, Jack Forbes, and Deborah Root have variously referred to as "wendigo psychosis [.. .. .] the cannibalizing and psychotic [.....] condition marked by greed, excessive corruption, violence, and egoism" (Sugars 79).5

8 While Clements’s play is decidedly focused on the women’s murders, I understand her overarching concern to be with the universally malevolent repercussions of contemporary society. The opening scene suggests that consumerism performs its identity; it infects everything in its path to such an extent that no one is capable of seeing the root of the problem. In other words, Clements inverts the audience’s semiotic relations and in the process begins to revalue the relationship between visible and invisible, present and absent. The bodies of the women, which the audience expects to see, remain invisible, while the bodies of trees and loggers are etched in its collective imagination.

9 As marked, concrete objects, bodies are visual reminders of the often-unremarked narratives of Self and Other. Phelan’s assertion that "the link between the image and the word [.....] is in every way related to what one can say" again comes to mind (Unmarked 2). For while visibility politics exist, they overlook their implicit dependence on the image (7). She goes on to argue that the desire for a broader scope of representation rests on the following presumptions:

- Identities are visibly marked. [...] Reading physical resemblance is a way of identifying community.

- The relationship between representation and identity is linear and smoothly mimetic. What one sees is who one is.

- If one’s mimetic likeness is not represented, one is not addressed.

- Increasingly, visibility equals increased power. (7)

Thus, one’s body is not represented, then. Not only is it stripped of its potential power in reality, it is also left out of language. There is no lexicon for recognition. Moreover, if somehow I recognize an Other, I am trained to translate her into something to which I can relate. "Representation," concludes Phelan, "reproduces the Other as Same" (3). So, if addressing the Other in theory requires a difficult process of rearticulation, then addressing her in practice means finding a way to rupture reality. Clements achieves this effect by delaying the audience’s introduction to the women of the play. This delay initiates a new lexicon of looking that begins to unsettle the audience’s normative relationship with representation. The audience encounters the women in a state Joan Retallack has termed in medias mess, in the midst of some of the most vulnerable and visceral moments of their lives (79). These are real women with real messy lives that the audience encounters. Scenes with the individual women create an intimate relationship with the audience: as Mavis sits in her chair yearning for human contact the audience is unable to reach her and can only watch as her chair develops human arms, holds her close, and eventually subsumes her. Nor can the audience intervene when Violet is accosted by a dresser. Instead the audience must bear witness as she is literally and figuratively compartmentalized. Stark slides stating the barest facts of their real-life deaths are juxtaposed with these viscerally human women. Clements makes palpable the arbitrary relationship between the image (the individual women) and the word (Woman) and in so doing calls into question habitual modes of representation. The live women on stage defy totemic representation and instead embody the shifting, playful, and arbitrary nature of the signifier. They are dead, yet they are the most vibrant characters on the stage. They moved in visible contradiction to the static words on the slides, which represent the totality of the media’s attention, and sustain the fiction that finite representation is possible. The oppositional images create a tension that renders the violence of representation unsettlingly plain for the audience or the reader. Unfortunately, this refiguration is undermined and undone in Unnatural and Accidental.

10 Unnatural and Accidental was directed by Carl Bessai and had a strong cast of actors. However, Tantoo Cardinal who plays Aunt Shadie, Carmen Moore who plays Rebecca, and Callum Keith Rennie who plays the barber, are unable to rescue the film from a stereotypical pedantry fraught with alienating acts of violence and utterly devoid of a sense of community among the women. Consider the opening scene: instrumental music girded with thumping drums grows louder as a camera pans a wide-angle panoramic shot of a forest. The scene quickly cuts to a darkened room. We see Aunt Shadie nude but with a sheet covering her lap. She is prone with eyes open smiling vacantly and caressing her breast. The shot widens to reveal a small, dingy apartment. A hologrammatic and clothed Aunt Shadie sits up out of herself and walks away from her prostrate other who says to her "You look good." The camera returns the viewer’s gaze to the naked Aunt Shadie who has bruises covering her head, arms, and breasts. She smiles to her clothed self and says, "No rush at all for Indians like us. Long line up on the other side, anyways." The scene fades into a thundering sky. Gone are the associative alignments between human and nature. The audience is not urged to make a connection between the living Rebecca, the felled trees, and her mother who calls to her as another tree teeters in the balance. Instead, Aunt Shadie’s passive acceptance of her role as "Indians like us" suggests that there is no other narrative for women like her. The image she presents is easily translatable.

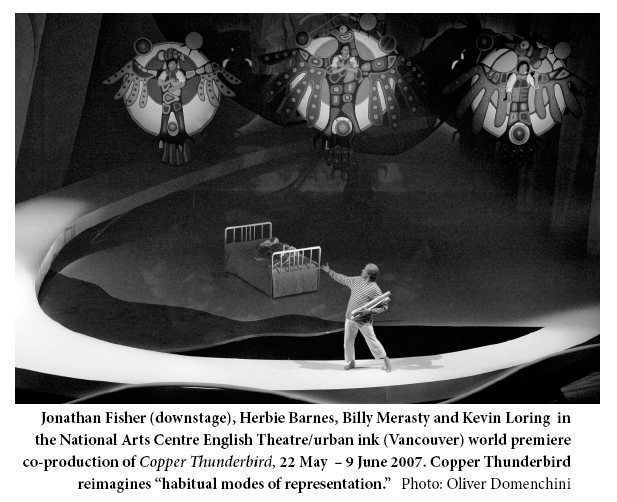

Jonathan Fisher (downstage), Herbie Barnes, Billy Merasty and Kevin Loring in the National Arts Centre English Theatre/urban ink (Vancouver) world premiere co-production of Copper Thunderbird, 22 May – 9 June 2007. Copper Thunderbird reimagines "habitual modes of representation."

Display large image of Figure 1

11 What is perhaps more unsettling about the opening of the film is what is not represented. Rose, the English switchboard operator whose appearance in the play sets into motion the radical community of women that is forged, is utterly absent. Instead the camera cuts to the interior of a taxi. This is our first image of Rebecca. She has her hair pulled tightly back and is wearing a dark, monochromatic suit. She appears agitated, and as the camera pans out to show her surroundings the audience sees the dissolution that is East Hastings. The camera pays most attention to a series of young Aboriginal women whose images recur throughout the film. These are the women who are named in the play, but here are referred to in the credits only by the colour of their clothing. They are each dressed predominantly in one bright colour. The juxtaposition with Rebecca’s suit suggests that these women are flamboyant, ebullient, and unwieldy. The camera slows as it takes in these women, focuses in, and urges the audience to consume the images on screen. Whatever the directorial intent, the result is predictable: these women are anonymous, here for you to look and touch with your eyes. You need not know their names. Suddenly, the taxi strikes one of the women. As she rolls off the hood she makes eye contact with a shaken Rebecca. "Be careful," she warns. Instead of making any attempt to ascertain the woman’s well-being, Rebecca looks away and continues her journey to her dying father’s bedside. Here, she is met by a character who is not in the play at all. A priest, clearly a close confidant of hers, meets her in her father’s hospital room. The priest plays a small but crucial role as facilitator in the film. It is clear that he is the one who has called Rebecca, and after her father reveals that he forced her mother to leave, it is the priest who comforts Rebecca and helps her begin her search for mother. As a shaken, wan Rebecca weeps over her prostrate father, the audience is left wondering why her mother was forced to leave. The camera then cuts to an Aboriginal man with long braids in what appears to be an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting led by Gilbert, leaving the impression that Rebecca’s father evicted his wife because he could see what she would become: just another drunk Indian.

12 This is not at all the direction taken by the play. In the play, Aunt Shadie’s self-induced resurrection reminds the audience that the text is not woven together by western mythology; Aunt Shadie is no Christ-figure called home by the Father. Rather, as Reid Gilbert suggests is typical of Clements’s approach, the "complex layering of myth and iconography operating simultaneously in more than one cultural system [...] form[s] a new typology of signs" (49). Reid Gilbert cautions that this is not to suggest that Clements’s drama operates outside the realm of her non-native audience members’ intelligibility, but rather that she troubles dominant ideologies and narrative structures by integrating Aboriginal mythologies with western ones. Clements disrupts normative essentialisms not only by crossing cultural borders, but also by exposing inherent and deep-seated hypocrisies and stimulating a radically different interaction between audience and performance.

13 "These new signs," says Gilbert, "add to earlier sign-vehicles. They are often quite translucent overlays that urge us to read through layers of the composite, multidimensional icon [...]. They reposition the spectator as subject" (49). In other words, because the audience can no longer easily translate difference into familiarity, it in turn is othered. Thus when Aunt Shadie rises out of her own dead body the audience is certainly meant to read traces of resurrection narratives, but the implications of a spectre emerging from her own murdered body simultaneously implicates the audience in her murder simply by recognizing the iconography of her dead body. Further, Clements interlaces Canada’s history of abuse to Aboriginal people with the concurrent semiotics of hauntology. Aunt Shadie’s exchange with the switchboard operator Rose (who is an English immigrant) depicts the interaction between western colonial mythologies and assumptions, and liminal Aboriginal ones:AUNT SHADIE. Excuse me.

ROSE. (not looking at her) Can I help you?

AUNT SHADIE. Yeah sure. I’m looking for a place to leave my baggage for a while.

ROSE. I’m sorry, I can’t do that.

AUNT SHADIE. Why, because I’m I’m…

ROSE. …naked. Yes, that’s it. You’ll have to register first. I can’t be taking just anybody’s baggage now, can I? Can you write your name?

AUNT SHADIE. Listen, I’m naked, not stupid.

ROSE. Oh. Well, I’m just trying to help you people out.

AUNT SHADIE. Why don’t you look at me when you say that?

ROSE turns slowly around revealing a black eye and bruises on her face.

AUNT SHADIE. Wow, they sure dragged you through it. (14-15)

In this exchange the audience undoubtedly identifies the implicit history of embedded racism and (white) cultural assumptions about the capacities of Aboriginal intelligence. Yet, this exchange does not merely address historic wrongs. Clements inserts semiotic markers in this exchange that are read by Aunt Shadie when she identifies with Rose’s bruises. The semiotic emphasis of experience sutures the concurrent narratives without obscuring the tear. The audience understands both the clash of cultures and Aunt Shadie’s ethical gesture of self identification in Rose’s battered face. Reid Gilbert states thatto position Canadian (theatrical) icons within the history of Canada in order to evaluate their importance in the development of a national consciousness is [...] to subscribe to the notion—now suspect—that one national history exists, or that the process of history making is somehow apart from the notion of creating theatre, the mimetic one to be weighed in terms of the absolute other. (50)And I agree with him that Clements’s integrations of iconic national narratives with narratives of (and by) the absolute other work to "reform the Canadian narrative" (50).

14 I would go one step further and suggest that Clements’s reform of the Canadian narrative is radically feminist insofar as it is embodied in the semiotic gesture of giving m(O)ther to the other woman. By identifying herself in the battered reflection of a British middle-aged white woman, Aunt Shadie begins to refigure the Canadian ideology of identity. An exchange occurs here, again at a threshold like the opening scene. Rose is a switchboard operator who facilitates communication between individuals. It is never clear where Rose’s switchboard is located though, and I want to suggest, given that she intercepts communication from some of the other murdered women, that Rose operates at the threshold of identification. She is the operator who operates on a rupture and mimetically mimics the function of poetic language as it animates the connection between the real and reality. For though she is the operator who is meant to connect people, Rose habitually misunderstands what people are saying. Instead it is Aunt Shadie who matter-of-factly points Rose in the right direction, thereby inverting naturalized power balances. Rose too has a slide that projects the details of her death: "Rose Doreen Holmes, 52, died January 27, 1965 with a 0.51 blood-alcohol reading. Coroner’s inquiry reported she was found nude on her bed and had recent bruises on her scalp, nose, lips, and chin. There was no evidence of violence or suspicion of foul play" (18-19). But while the details of the slide are accurate, it is Aunt Shadie who truly gives Rose the gift of death through her recognition and acknowledgement of Rose’s bruises. Aunt Shadie realizes that she and Rose are different, but she does not co-opt Rose’s experiences as her own. Rather, by recognizing and giving voice to Rose’s injuries, Aunt Shadie assumes the responsibility of bearing witness to the life (or death) of another. She does not become the white woman’s shamanic spiritual leader, though. Instead, Rose is left to educate herself about communication by watching the way that the other women communicate with each other. Rose’s confusion, latent racism, and prudishness are juxtaposed with Aunt Shadie’s matter-of-factness. And while neither woman is depicted as "better" than the other, it is impossible to overlook the fact that it is Aunt Shadie who initiates conversations. She is the one who deliberately engages in discourse with the other without translating the other as same. The performers essentially lead the audience through ethical acts of recognition and teach the audience how to bear witness to the other.

15 There are myriad discrepancies between the play and the film, but it is this first omission of the exchange between Rose and Aunt Shadie that allow for the rest that follow. Without the ethics of witnessing that Aunt Shadie initiates, Rose would not be allowed into a community of women. The repercussions are highly visible in the film. There is no scene where Rose calls to check on Mavis’s well-being, nor does the viewing audience witness the murdered women surround, sing to, and support Violet as she narrates her own death. Instead, the camera keeps the women separate, showing them in a dilapidated hotel, all looking out from their own solitary rooms. And in the final scene when Rebecca murders the Barber it is not

in his barbershop with all the other women as witness. In the play this final scene is crucially communal. As Rebecca begins to shave the Barber, who is still under the impression that he will overpower her as he did the others, Aunt Shadie appears in the mirror, bodied forth by the effigy of her stolen braid:[The Barber] closes his eyes. As she spreads foam on his face, a forest reflects in the mirrors as it is being covered by a billowing snow… A voice from the darkness approaches through the landscape… At first just a movement and glimpses of brown.

AUNT SHADIE. I used to be a real good trapper when I was young. You wouldn’t believe it, now that I’m such a city girl... I would walk down that trapline...

REBECCA. I would walk down that trapline...

AUNT SHADIE... like a map, my body knowing every turn, every tree, every curve the land uses to confuse us.

REBECCA... like a map, my body knowing every turn, every lie, every curve they use to kill us.

REBECCA / AUNT SHADIE. I felt like I was part of the magic that wasn’t confused.

REBECCA. The crystals sticking to the cold and the cold sticking to my black hair, my eyebrows, my clothes, my breath. A trap set. (124-25)

As Rebecca raises her hand to slit the Barber’s throat, he opens his eyes and nearly slits hers instead, but Aunt Shadie and the rest of the murdered women emerge from the mirror. They hold Rebecca’s hand steady and together they kill the Barber. Killing the Barber is literal, but on another level the act can be read as killing the father, though not in the strictly Oedipal sense. In Clements’s rearticulation, it is a woman who kills and she is killing the man who prescribed her narrative and sustained the archive. Clements’s interlacing narrative reaches across generations and across the gulf between real and reality to embody a future-oriented investment. The rearticulated orders of the real and the imaginary band together in an impossibly possible body (both spectral and somatic) and fracture the symbolic order.

16 By contrast, the film’s revision of this scene has Rebecca in the backseat of an old car. This new site—the backseat of the car— suggests among other things a loss of innocence, the scores of women disappeared along British Columbia’s Highway 16, sex workers who enter cars and never return from "bad dates." Thus, while the mirror remains, it is refigured as a rear-view mirror, which, while suggesting hindsight, complicates the remarked and revalued relationship that the play sets up between Rebecca and Aunt Shadie. The mirror scene of the play is an imaginative return to the Real, where Rebecca’s words and her mother’s intermingle and create a new narrative together. In this version, Rebecca recognizes her m(O)ther, but does so outside the patriarchal lexical archive. In the film, though Aunt Shadie is there to offer encouragement, she does not defy possibility (the real) by reaching out to steady Rebecca’s hand. Instead, because she is already marked and misrecognized as Other—translated as Same—the Barber’s murder is simply as sensational as the ones he executed. The film makes Aunt Shadie subject to representation. Similarly, the women, who are wholly absent from the murder, are denied entrance into the radical community established in the play.

17 Clements’s play takes on the risk of real bodies and in doing so challenges the audience to become aware of their relationship with the other, if only in the space of the theatre or the space between the hand that holds, the eyes that read, and the text that performs. Her work radically undermines the socio-cultural semiotic archive. However, as the adaptation demonstrates, such radical revisions are all too susceptible to recapitulation. In his work considering the ethical potential of art, Theodor Adorno makes an observation that crystallizes what I see at work in Clements’s play: the revisionary relationships between reader and text, audience and actors that call for a new kind of recognition and representation. He says,In the final analysis aesthetic behavior might be defined as the ability to be horrified [...] the subject is lifeless except when it is able to shudder in response to the total spell. And only the subject’s shudder transcends that spell. Without that shudder, consciousness is trapped in reification. Shudder is a kind of premonition of subjectivity, a sense of being touched by the other. (455)Adorno writes on the edge of referentiality, gesturing both to theory/real and to practice/reality. He speculates about how aesthetics can trigger identification and recognition between subjects. The shudder, which is both literal and theoretical, breaks the power which keeps subjects separate from one another. When my body shudders at the sight of your suffering, I take on the reality of your pain. In so doing, I acknowledge you, I see you, and I am responsible for bearing witness. I am responsible for recognition.

18 The Unnatural and Accidental Women is performance on the edge of referentiality. The narrative action of Clements’s play touches the body of the audience, and in so doing imbues it with an ethical responsibility to the body of the other. In this last moment of the play Aunt Shadie and her daughter Rebecca finally see each other, they embrace, and behind them the women sit down to a banquet. Their voices "become the sound of trees" (126), but touched as they are by each other, by the body of the audience, they are unfelled. Protected by the recognition of the other the body is safe "in the dreaming part inhabiting us" (Brossard 68). Clements figures the body as imaginary and as real. This impossibly possible body, as exemplified in the racialized bodies of the Aboriginal women subjects, demands and incites a new way of looking at one another. The racialized female body in performance demands that the audience shudder, and in that shudder the archive shatters.

19 If the archive stabilizes images and prescripts recognition, then the archiviolent text undoes passive recognition and capsizes the viewer’s (reader’s, human’s) passive engagement. However, as I have worked to demonstrate, the slippage between archive and archiviolent is unstable territory. Indeed, as the celluloid Unnatural and Accidental demonstrates, what is lost in this particular process of adaptation is not just the physical closeness of bodies on stage and of the audience. As Linda Hutcheon has observed, adaptation is risky business, and we would do well to consider the adaptation on its own terms, not simply on the basis of its fidelity to the original: "Whether it be in the form of a videogame or a musical, an adaptation is likely to be greeted as minor and subsidiary and certainly never as good as the original," cautions Hutcheon (xii). She goes on to explore the ways that "shifting the focus from particular individual media to the broader context of the three major ways we engage with stories [...] allows a series of different concerns to come to the fore" (xiv). With this approach in mind, it is particularly interesting to note that the adaptation of Unnatural and Accidental is from performance to performance, or what Hutcheon would refer to as showing-to-showing. In this case, the means and medium of representation do not shift, yet something of substance is lost such that I, a reader of a text of a live performance, am left unmoved when experiencing the cinematic adaptation. Where Unnatural and Accidental fails then is in its reproduction of habitual modes of representation. The film viewer is not compelled to question her relationship or responsibility to the women on screen. Otherness is reproduced and passes as sameness, and familiarity instead of confronting the viewer and challenging her to experience and recognize another.

20 Phelan argues that there is a paradox in "using visibility to highlight invisibility," and offers the example of gays and lesbians who choose to pass as heterosexual (97). If sexual preference is virtually invisible because it is assumed to be the norm, then choosing to pass as such underscores the "‘normative’ and unremarked nature of heterosexuality" (97). Phelan reads Jennie Livingston’s Paris is Burning (1991), a documentary of the culture of competitive drag balls in Harlem in the late 1980s, and suggests "misrecognition contains within it an affective power" (106). While my instinct may be to change what I see but do not recognize into something I know, I can effect the change only by repressing the "fact of the transformation" (107). In other words, I mark the unmarked by killing its difference. Or, in the case of Unnatural and Accidental, I am cast as a passive viewer who does not need to know anything about the women on screen other than the colour they are assigned to identify them. Rather like the function of the absent referent, no? By arresting difference I not only strip the other of her specific perception and experience of the world, I translate her into something knowable, and in that translation I recuperate her to the patriarchal archive. Remembering the murder of Venus Xtravaganza who was a pre-surgery (male to female), Phelan ruminates: "[director] Livingston implies that Venus, found under a bed in a cheap hotel after four days, was murdered because she could not finally pass as a woman" (109). But Phelan realizes that this assumption is in effect what I mean when I suggest recuperation into the patriarchal archive. There is a distinct possibility that "Venus was murdered precisely because she did pass. On the other side of the mirror, which women are for men, women witness their own endless shattering. Never securely positioned within the embrace of heterosexuality or male homosexuality, the woman winds up under the bed, four days dead" (109). Or on a pig farm. Or in a barbershop. Without an engagement with the other I am reminded of Lacan’s trot-bébé, looking in the mirror and recognizing myself only because I am not that Other, that unreal reflection.

21 The mirror in the final scene of Clements’s play is not a woman reflecting man back to himself, as in the Western myths of psychoanalysis or Plato’s cave. Rather, it is the women reflecting and reaching for one another. But this scene is absent from the film, which ends with Rebecca, soaked in the Barber’s blood, walking down a deserted street alone. The archive remains intact and the moment of destabilizing (mis)recognition is lost. For while I could argue that as a film the work may reach a larger audience, I cannot ignore the fact that it would do so by sacrificing the majority of the play’s radical gestures. Without the scenes of camaraderie and community that the women create and sustain for one another, the film is at best a stark depiction of the isolated urban existence, especially for lower class, middle aged, and racialized women. Further, it is hard to ignore that the film is categorized as a "thriller," which suggests that it is merely entertainment. How will we see each other if we are consigned and contained? Clements’s play is radical because its narrative, whether seen live with an audience of many or read as text alone, incites a performative recognition of the other: the action of the narrative, itself an artistic adaptive revision of an historical event, ruptures normative narratives of witnessing. But without an inter-ventionist adaptive revision of my critical reading skills as an audience member, and as a member of society, the radical un(re)marked moment of recognition is lost, the mirror unshatters, and I forget that I ever shuddered at all.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Trans. John Cumming. New York: Continuum, 1972.

Brossard, Nicole. Fluid Arguments. Ed. Susan Rudy. Trans. Anne-Marie Wheeler. Toronto: Mercury P, 2005.

Churchill, Ward. "Nobody’s Pet Poodle." Indians Are Us? Culture and Genocide in Native North America. Monroe, ME: Common Courage, 1994. 89-113.

Clements, Marie. "marie clements." Web. 13 Feb. 2009. <http://www.marieclements.ca/index.asp>

— . The Unnatural and Accidental Women. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005.

The Cultural Memory Group. Remembering Women Murdered By Men: Memorials Across Canada. Toronto: Sumach, 2006.

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Trans. Eric Prenowitz. Chicago: Chicago UP, 1998.

— . Spectres of Marx: The State of Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. Trans. Peggy Kamuf. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Forbes, Jack D. Columbus and Other Cannibals: The Wetiko Disease of Exploitation, Imperialism and Terrorism. Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 1992.

Gilbert, Reid. "‘Shine on us, Grandmother Moon’: Coding in Canadian First Nations Drama." Aboriginal Drama and Theater. Ed. Rob Appleford. Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 2005. 49-58.

Hopkins, Zoe Leigh. "Well-Written, Well-Performed Tragic Tale." Rev. of The Unnatural and Accidental Women. Raven’s Eye 4.7 (2000): 7.

Howard, Rebecca, and Shirley A. Huston-Findley, eds. Footpaths & Bridges: Voices from the Native American Women Playwrights Archive. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2008.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Kamuf, Peggy. "To Follow." Derrida’s Gift. Spec. Issue of differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 16.3 (2005): 1-15.

Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked: Politics of Performance. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Retallack, Joan. The Poethical Wager. Berkeley: The U of California P, 2003.

Root, Deborah. Cannibal Culture: Art, Appropriation, and the Commodification of Difference. Boulder: Westview, 1998.

Sugars, Cynthia. "Strategic Abjection: Windigo Psychosis and the ‘Postindian’ Subject in Eden Robinson’s ‘Dogs in Winter.’" Canadian Literature 181 (2004): 78-91.

Taylor, Diana. "Performance and/as History." TDR 50.1 (2006): 67-86.

— . The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham: Duke UP, 2003.

Notes