Articles

Romance, Recognition and Revenge in Marie Clements’s The Unnatural and Accidental Women1

Karen BamfordMount Allison University

Abstract

This essay considers the relationship of Marie Clements’s The Unnatural and Accidental Women to European traditions of drama and folk narrative, and especially its relation to the genres of revenge tragedy and romance. It argues that Clements transforms and subsumes the latter in a feminist, maternal romance. In contrast to the traditional family romance, from Homer’s Odyssey to Shakespeare’s Pericles, and its folktale analogues (Cinderella and Peau d’Asne, and the related Dear as Salt), which operate to gratify paternal wishes, Clements’s romance gratifies a mother’s desire for reunion and reconciliation with her daughter. In contrast to the resolution of Renaissance revenge plots, in which the revenger typically dies to satisfy the claims of justice, here the female protagonist achieves a rebirth symbolized by the recognition she shares with her mother. Like the romance tradition which it transforms, the play offers us a vision of an ideal world, here symbolized in "the first supper" that concludes the play.Résumé

Cet article s’intéresse au rapport entre la pièce The Unnatural and Accidental Women de Marie Clements et les traditions européennes du théâtre et du récit folklorique, surtout en ce qui a trait aux genres de la tragédie de vengeance et du récit romantique. L’auteure fait valoir que Clements transforme et module ce dernier genre en romance féministe et maternelle. Contrairement à la romance familiale traditionnelle, de l’Odyssée d’Homère en passant par le Périclès de Shakespeare, et des contes populaires analogues (Cendrillon. Peau d’Âne et Bien comme le sel, qui portent sur le même thème), où il faut répondre aux souhaits du père, la romance de Clements répond au désir qu’a une mère de retrouver sa fille et de se réconcilier avec elle. Contrairement à la résolution des complots de vengeance de la Renaissance, dans lesquels le vengeur meurt généralement pour satisfaire la justice, dans ce cas, la protagoniste renaît symboliquement dans la reconnaissance partagée avec sa mère. À l’instar de la tradition romantique qu’elle cherche à transformer, la pièce nous offre une vision d’un monde idéal, symbolisé par le «.premier repas.» qui lui sert de conclusion.1 I begin by summarizing some well-known facts: Marie Clements’s The Unnatural and Accidental Women is based on a series of killings that took place in Vancouver between1965 and 1988. Most of the victims were middle-aged Native women who frequented Vancouver’s lower eastside, its Skid Row. The murderer was a white man—a barber called Gilbert Paul Jordan— who induced the women to drink fatal amounts of alcohol. As Clements explains in a prefatory note to her play, several coroner’s reports declared the deaths to be "unnatural and accidental" (5). Although he eventually served six years for manslaughter, Jordan was never convicted of murder: indeed, he was living on probation in the Vancouver area when Clements’s play premiered at the Firehall Arts Centre in November of 2000.2 In answer to the failure of the Canadian justice system and to the social conditions that allowed Jordan to prey upon the women, Marie Clements’s play proposes an alternative: a therapeutic fantasy in which the women move from the isolation and violence of their deaths to form a community after death—a community that both repairs the emotional wounds of the women’s early lives and takes action to stop the killer.

2 Other critics have usefully situated Clements’s play within the context of First Nations’ culture.3 In this essay I would like to consider instead the play’s relationship to European traditions of drama and folk narrative, and especially its relation to the genres of revenge tragedy and romance. As its editors, Monique Mojica and Ric Knowles, observe, The Unnatural and Accidental Women combines elements of "post-modern collage, pre-modern quest narrative, and early modern revenge tragedy" (364). Reid Gilbert, who analyzes the way the play "denaturalizes" genre, points to even more narrative categories, including "police story," "contemporary love story [,...] fictional and utopian revenge, and [...] native dreams of a redemptive North" (133). At the risk of oversimplifying the play’s complexity, I propose to isolate two of the primary genres at work—quest-narrative and revenge tragedy— and to examine the way Clements transforms and subsumes the latter in a feminist, maternal romance.4 As in Shakespearean romance, recognitions are crucial to the comic resolution: here Rebecca, a thirty-year-old writer and the daughter of one of the murdered women (called Aunt Shadie), searches for the mother who abandoned her as a child, while her mother, in the spirit world, searches for Rebecca. They meet at the play’s climax, when Aunt Shadie and the other dead women intervene to save Rebecca from the barber and to help her kill him. In contrast to the resolution of Renaissance revenge plots, in which the revenger typically dies to satisfy the claims of justice, in Clements’s play Rebecca achieves a rebirth symbolized by the recognition she shares with her mother. Immediately afterwards the murdered women sit down to a banquet together. In short, this is a festive resolution for everyone except the barber, who experiences a dramatic reversal and recognition, as he sees his victims return from the dead to claim his life. Part of the satisfaction the play offers its audience is thus the fantasy not only of the women taking collective action to stop the killer, but also of the barber’s recognition of their agency.

Romance

"Romance, being absorbed with the ideal, always has an element of prophecy. It remakes the world in the image of desire." (Beer 79)3 I have coined the phrase "maternal romance" to describe what I will argue is Clements’s radical and feminist transformation of the genre. Before I turn to a more detailed discussion of the play, I would like to consider the romance tradition briefly. Romance is a protean genre, notoriously difficult to define; however, I am focusing here specifically on what we might call the family romance.5 Rooted in ancient Mediterranean cultures, this tradition is mediated to us powerfully through Shakespeare’s final plays, in which family members are separated, suffer apparent deaths, and are providentially reunited. These romance plots, ancient and early modern, reflect the interests of a patriarchy in which women mattered primarily in relation to men: as daughters, wives, or mothers of males. (Significantly the recognitions in extant Greek tragedy include scenes between husband and wife, brother and sister, and mother and son, but not mother and daughter.6) It is thus not surprising that in these stories, where, as Shakespeare’s Gower puts it, "wishes fall out as they’re willed" (Pericles 5.2.16), the wishes that shape the happy endings are primarily those of men. Fathers generally get what they want; much less often mothers get what they want; and if they do, their gratification is a minor aspect of the plot’s resolution.7 This rule of patriarchal wish fulfillment is preeminently true of The Odyssey, the "fountainhead" of romance (Reardon 6), in which the hero returns, as if from the dead, after a twenty-year absence to recover his son, his wife, and his father. In the Biblical story of Joseph (Gen. 37-47), the hero is separated from his father and brothers but providentially reunited with them after his rise to power in Egypt. In Heliodorus’s Ethiopica—"the apogee of ancient romance," according to Heiserman (186)—the figure of the bereft father is multiplied: the heroine is lost and recovered not only by her biological father, the King of Ethiopia, but by three surrogate fathers.8 The Latin romance of Apollonius of Tyre, the original of Shakespeare’s Pericles, culminates in its hero’s miraculous recovery first of his daughter and then his wife.9 In this case the mother recovers her daughter and husband, but that three-way reunion is relatively perfunctory: the emotional weight is on the earlier, marvelous reunion of father and daughter.

4 Shakespeare’s King Lear is an abortive romance: here the father recovers the daughter only to lose her again. However, Shakespeare’s source play, the anonymously authored True Chronicle Historie of King Leir (c. 1590), features the happy ending his first audience probably expected of this story: the earlier Leir recovers his daughter and in doing so gains an ideal son-in-law to whom he bequeaths his crown (32.2635-9). The King Lear/Leir story is related to innumerable oral tales, including the Cinderella story, in which a father loses a daughter he incestuously desires, but nevertheless regains her and her forgiveness in the happy ending.10

5 My point here is twofold. I wish to emphasize first the persistence and popularity of the paternal fantasy Shakespeare dramatized so powerfully in King Lear, the fantasy of a father’s forgiveness by his wronged daughter. "No cause, no cause," weeps Cordelia to the penitent Lear (Lear 4.6.69). The folktale analogues of this reconciliation are widespread and long-lived.11 Second, I would like to emphasize the asymmetrical treatment accorded to bad fathers and bad mothers in the oral tradition of which these tales are part (type 510, Cinderella and Peau d’Asne (293-6), and the related type 923, Love Like Salt (555-7), in Uther’s classification of folktales). In the "Cinderella" stories (sub-type 510A), maternal figures are split into two radically opposed kinds: the deceased, good natural mother, who may aid the protagonist from beyond the grave, and the living, bad stepmother whose oppression she has to escape. Crucially the goal of the story—the protagonist’s happy marriage—does not include reconciliation with the abusive stepmother. If the stepmother does appear at the tale’s conclusion, she is punished, as in a Finnish version where she is put into a spiked cask and killed (Cox 40). By contrast, in stories of the Peau d’Asne type (sub-type 510B, 295-6) and the related Love Like Salt (type 923, 555-7), the abusive father typically repents his error and achieves reconciliation with his daughter. In short, bad fathers may be redeemed; bad mothers may not. Bad fathers get a second chance; bad mothers do not. Moreover, mother-figures in the "Peau d’Asne" tales frequently act as scapegoats for the father’s sins: the dying mother exacts a promise of her husband that he will only wed a woman as beautiful as she, or who can fit something of hers, thus requiring her replacement by her own daughter. A surrogate mother may also help the father in his attempted incest. Thus in the Egyptian tale "The Princess in the Suit of Leather," an old nurse proposes to the King that he should marry his daughter since she is the only one who fits her mother’s bracelet. The heroine flees the unnatural marriage, but is reunited with her father after she succeeds in wedding a prince. When the old woman who proposed the incestuous match has been flung off a cliff, the king gives half his kingdom to his daughter and her husband, and they live happily ever after. In these tales, as in The True Historie of King Leir, the happy ending is defined by the triangle of father, daughter, and son-in-law, in which the female links the old and young males.

6 We recognize this happy triangle in the festive conclusions of Shakespeare’s romances where fathers—Pericles, Cymbeline, Leontes—recover daughters who bring them sons-in-law.12 When Pericles regains Marina he immediately betrothes her to Lysimachus. Cymbeline regains Innogen and thus Posthumous as a son-in-law, though since he also recovers his long-lost twin boys, Posthumus is not as crucial to the succession as is Lysimachus. (We should also note that Innogen’s wicked stepmother is culled from the family party: she dies a punitive death, "[w]ith horror, madly dying, like her life, / Which being cruel to the world, concluded most cruel to herself" [5.6.31-33].) Prospero, who notably designs Miranda’s match with Ferdinand, gains an ideal son-in-law, while Alonso recovers his son and gains a daughter-in-law. But The Winter’s Tale complicates the general rule of primary paternal gratification. Here, although the erring patriarch Leontes does recover a daughter who brings him a sonin-law, as well as his wife, the more emotionally significant reunion is the one between mother and daughter; Shakespeare doesn’t even stage the father-daughter reunion. Hermione says she "preserv’d" herself in the hope that her daughter would be found (5.3.127), and only returns when Perdita does. She comes back to life for her daughter, not her husband, and it is to her daughter that she speaks when she finally does. I call this an instance of maternal romance because the plot preeminently satisfies a mother’s desire for reunion with her child. I contend that such satisfaction is rare enough in the romance tradition and its folk tale analogues to be remarkable.13

7 Like The Winter’s Tale, The Unnatural and Accidental Women features a mother whose longing for her daughter is so strong that she returns from the dead to find her. Indeed, Aunt Shadie’s first and last words are her daughter’s name. Significantly, however, while Hermione, the idealized mother and wife, embodies the patriarchal virtue of chastity, Aunt Shadie, who abandoned her family for life on Skid Row, resembles a conventional type of bad mother and wife. That stereotype, however, proves inadequate in the world Clements constructs, a world in which Aunt Shadie embodies "mother qualities of strength, humour, love, [and] patience" (Clements 5), and in which she is allowed a reunion with the daughter who has finally forgiven her abandonment. Paraphrasing Gillian Beer (79), we might say that in this play Clements remakes the world in the image of maternal desire— that is, the desire of a mother for her child.

Recognition

"Recognition [...] is a change from ignorance to knowledge, producing love or hate between the persons destined by the poet for good or bad fortune." (Aristotle XI.2) "[...] being invisible can kill you." (Clements 82)8 In addition to the climactic and emotive recognitions of the play’s final moments, to which I will return later, Clements builds her maternal romance through a series of earlier recognitions between "persons destined by the poet for good [...] fortune" (Aristotle X.2) in the afterworld: the dead women come together, moving from ignorance to knowledge of each other, from the isolation of their deaths into a community. During the first act of the play we see the deaths of eight women represented in various surreal ways.14 They have names and identities: they are individuals. Clements gives us glimpses of their particular broken lives, the families they have lost, the emotional needs that make them vulnerable to the barber. However, these scenes of past violence and grief—the motive for the revenge plot—are framed and, I will argue, made bearable by the divine comedy of the romance structure. In counterpoint with the painful dissolution of the women’s lives, we see not only Rebecca in the eastside bar where she’s come to look for her mother (13), we also see a community begin to emerge in a space Clements describes with characteristic generosity as the "[h]appy hunting ground and/or heaven" (7). There the two oldest women, Aunt Shadie and Rose, though they meet as strangers, soon form a close bond: their implicit recognition of each other as sisters establishes the basis of a matriarchal community in which they act as elders. Aunt Shadie’s function is suggested by her name: she is an "Aunt," a surrogate mother, to the younger women.15 Rose, a switchboard operator in the "happy hunting ground and/or heaven," announces her own maternal function. As she explains,I’ve always been right here. No matter where I am, I am in between people connecting [...] I wait for the cry like a mother listening, hoping to slot the right thing into its void—hoping to be the one to bring about the pure answer. Again, the pure gentle darkness that says I have listened and you were lovely, no matter how loud your beeping cry becomes, no matter how many times I wanted to help but couldn’t. There is something maternal about it, the wanting to help, the trying, going through the motions on the switchboard, but in the end just being there it seems just listening to voices looking for connection, an eternal connection between women’s voices and worlds. (19)

9 Significantly, the community they form crosses racial barriers. Though Aunt Shadie, like most of the women, is Native, Rose is English—a racial difference that is first humorously emphasized then transcended.16 Later Aunt Shadie explains to Rose why she left her Metis husband and their daughter: "I was afraid she [Rebecca] would begin to see me the way he saw me, the way white people look up and down without seeing you–like you are not worthy of seeing. Extinct, like a ghost [...] being invisible can kill you" (82). Thus, according to Aunt Shadie, the original violence that destroyed her family twenty years earlier, the trauma that drove her away—into the Skid Row bars and ultimately to her death—was a failure of recognition: her husband did not see her, could not see her. However, if, as Aunt Shadie claims, being invisible can kill, the play suggests that recognition, along with acceptance and affirmation, can heal. When Aunt Shadie and Rose first meet, the former is naked and Rose’s face is severely bruised, but in a first gesture of recognition and relationship Rose lends Aunt Shadie her cardigan (16): when they next meet, Aunt Shadie is "putting trapping clothes over her young housewife clothes" (37-8), symbolically reappropriating the culture she was born into, and "ROSE’s face is no longer bruised" (38). The healing has begun. When, subsequently, Aunt Shadie tells Rose that "being invisible can kill you," Rose replies, "I see you and I like what I

see":AUNT SHADIE. I see you—and don’t worry, you’re not white.

ROSE. I’m pretty sure I’m white. I’m English.

AUNT SHADIE. White is a blindness—it has nothing to do with the colour of your skin.

ROSE. You’re gonna make me cry.

AUNT SHADIE. You better make us some tea then.

ROSE. That will help?

SHADIE. No, but it gives you something to do. (82-3)

10 And so Rose "goes through her serious ritual of making tea" (83). Although Aunt Shadie prescribes the preparations for tea as a distraction for Rose, the "serious ritual of making tea" is just that, a symbolically significant ritual of incorporation. Drinking tea together, like eating together, confirms membership in a community. Later Violet, the youngest of the women, sets a dinner table in the "happy hunting ground/heaven" with Rose; she places the silverware "in a setting ritual" (106)—an action that somehow allows Violet to reach maturity with Rose’s help. (Rose instructs Violet about the meaning of existence as they work.) When Violet places the last knife, she turns to look at Aunt Shadie, who nods: Violet walks away "like a woman" (107). The healing the play represents thus depends upon the women’s willingness and ability to recognize each other as family in spite of their differences.

11 As the first act draws to a close Aunt Shadie summons three women from the barbershop mirror: they begin to emerge as she "calls to them in song and they respond, in song, in rounds of their original languages" (58). These three then "call to each fallen woman, in each solitary room. THE WOMEN respond and join them in song and ritual as they gather their voice, language and selves in the barbershop [...]. [The song] grows in strength and intensity to the end of Act 1 where all their voices join force" (58).

12 Though their song is primarily in their original languages—and will thus be unintelligble to most readers and theatre audiences— the English refrain, "Do I hear you sister like yesterday today," emphasizes their sisterhood across time and space. The women gather to watch Rebecca, sitting in the bar, and also the barber, who has clearly marked Rebecca as a potential victim. In counter-point to the women’s spectral surveillance of the barber and Rebecca (the revenge plot), we see Aunt Shadie nurturing Violet (the romance plot). Violet, who "becomes smaller and more childlike" after death, backs away from the scene of her murder to sit on a swing: "AUNT SHADIE moves tenderly behind her and begins to swing her," replacing the father Violet recalls from her childhood (62). Although Violet wants to join the other women in the bar, Aunt Shadie won’t let her: "No, you’re too young," she tells Violet. "Besides," she adds, "I need someone to walk with me" (63), like a mother who soothes a child by insisting on her importance. In the "happy hunting ground and/or heaven," Aunt Shadie introduces Violet to Rose, who embraces her. "She’s squishing me," Violet complains, still childlike:AUNT SHADIE. She’s hugging you.

VIOLET. No, she’s squishing me.

AUNT SHADIE. Hugging—squishing. It’s all the same thing.

VIOLET. The same what?

AUNT SHADIE. Love. (64)

Visually the triangle of Aunt Shadie, Violet, and Rose (mother/daughter/mother), a consolatory emblem of regeneration, offsets the larger group below in the barroom, where, as the lights begin to fade, the gathered women "shift all their energy towards the BARBER" (65). The first act thus concludes with the elements of both romance and revenge in place and ready for fruition.

Revenge

"A mourning woman is not simply a producer of pity, but dangerous." (Foley 55) HEKABE. These tents hide Trojan women.AGAMEMNON. You mean the prisoners of the Greeks?

HEKABE. With them I shall take vengeance on my murderer.

AGAMEMNON. And how can women prevail over men?

HEKABE. There’s a strange power, bad power, in numbers combined with cunning. (Euripides, Hekabe 139)

13 With the killing of the Barber at the end of act 2 the play fulfills the expectations of revenge raised in act 1. I would like briefly to consider the genre of revenge tragedy before returning to the romance structure.

14 Although revenge in ancient Greece, as Burnett argues, was not in itself unethical, immoral, or illegitimate,17 the revenges exacted by women in Greek tragedy are arguably so horrific as to alienate the sympathies of contemporary audiences.18 As Aristotle states flatly, "[t]here is a type of manly valour; but valour in a woman, or unscrupulous cleverness, is inappropriate" (XV.2), and women who demonstrate manly valour and unscrupulous cleverness in achieving revenge are demonized in Greek tragedy.19 Thus Blondell observes, "when the violent, vengeful nature typical of the heroic [Greek] male is unleashed in the person of a woman, it leads to acts of appalling violence against intimate family members" (164-65). Euripides’s Medea, "the incarnation of disorder" (McDermott), murders her sons to punish her husband. As Lee Sawchuk has argued persuasively, "Medea’s victory comes at the cost of her femininity and her humanity."20 Pursuing "masculine" revenge, she destroys herself as woman and "earns the horrified condemnation of her community" (Blondell 165). Euripides’s Hecuba (Hekabe) is also a mother who murders children, though not her own: to revenge the death of her son, and aided by the other Trojan women, she slaughters the infant sons of Polymestor before blinding him with their brooches. In sum, however much sympathy an ancient Greek audience was prepared to offer a male avenger like Orestes, tragedy has from its inception demonized female anger, the female avenger, the "strange power, bad power, in [female] numbers combined with cunning" (Euripides, "Hekabe" 139).21

15 In Renaissance drama, where revenge runs counter to the Christian ethos of the dominant culture, the quest for revenge typically entails the protagonist’s psychic disintegration. In Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy—one of the most popular and influential plays of the period—Hieronimo, grieving for his murdered son, goes mad before effecting the deaths of the villains, killing some bystanders, biting out his tongue and finally stabbing himself. In Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, heavily influenced by Kyd, the hero, grieving for a daughter (who has been raped and mutilated), also goes mad, and in his madness slaughters the rapists like pigs, feeds their flesh to their mother at a banquet; kills his daughter to end her shame; and completes his revenge by slaying the evil Empress Tamora. Female revengers are no less monstrous than their male counterparts: in Titus Andronicus Tamora avenges the sacrifice of one son by urging her surviving sons to rape Titus’s daughter: "away with her," she tells them, silencing Lavinia’s pleas for immediate death, "and use her as you will—/ The worse to her, the better loved of me" (2.3.166-67). In The Maid’s Tragedy, by Beaumont and Fletcher, Evadne takes revenge on the King who has sexually corrupted her by tying him to his bed while he sleeps, then, deaf to his pleas, repeatedly stabbing him: she herself dies, as Allman observes, "wild and unmourned, neither woman nor man" (140). The general rule in Renaissance drama is that the revenger loses his—less frequently, her—humanity and dies appropriately to restore order.22

16

The Unnatural and Accidental Women seems to me remarkable in its revision of this generic convention. Rebecca does not become monstrous in taking revenge on the barber, in part because the killing is not a premeditated act; it is spontaneous. This spontaneity is in strong contrast to all the revenges listed above, which are the fruit of careful planning. Indeed the artfulness of the revenge, in classical and Renaissance drama, is usually a source of self-conscious pride for the revenger. But Rebecca is seeking her mother, rather than her mother’s killer, and she acts on impulse when she first attempts to slay him. When she does succeed in killing him it is an act of self-defence: he very nearly kills her instead. Most importantly, perhaps, Rebecca acts in concert with her dead mother and the other women. The barber’s blade "is about to cut her open," whenAUNT SHADIE emerges from the landscape as a trapper. She stands behind REBECCA. She puts her hand over REBECCA’s hand and draws the knife closer to the BARBER’s neck. He looks up and panics as he sees AUNT SHADIE and the WOMEN/TRAPPERS behind her. Squirming, they slit his throat. (125)

Aunt Shadie’s hand is on Rebecca’s hand, giving her the strength to draw the blade. The artistry of this revenge is thus not Rebecca’s; it is not even Aunt Shadie’s or that of the others who cooperate in the revenge. We might say the design of the revenge is providential: whatever force brings the women together in "the happy hunting ground and/or heaven," whatever force allows Aunt Shadie to find Rose, and Violet to find them both and herself, brings them all to the barbershop at the crucial moment. This is the way the universe is organized.

17 Significantly, too, the killing of the barber is framed by Aunt Shadie’s memories of working the trapline. Just before Rebecca picks up the razor we hear (but don’t yet see) Aunt Shadie saying, "I used to be a real good trapper when I was young [...]" (124). As she speaks Rebecca joins in, echoing phrases, until they say in unison: "I felt like I was part of the magic that wasn’t confused" (125). At this point they are both "part of the magic," unconfused, and once Aunt Shadie’s hand is on Rebecca’s they deal with the Barber as effectively as Aunt Shadie once dealt with the trapped animals.

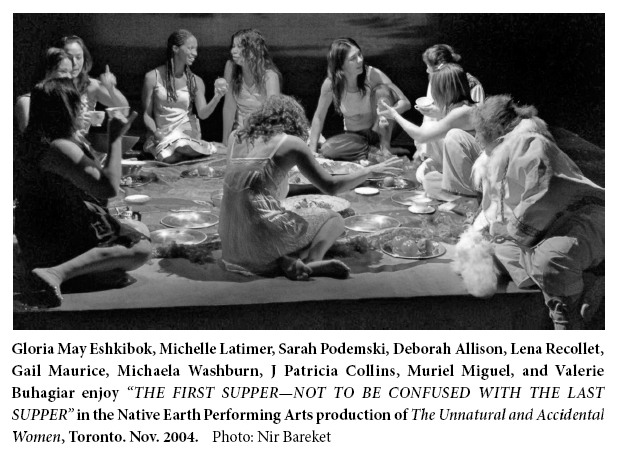

18 As horrific as this killing must be on stage—with the red blood on the white barber’s apron, like blood on snow—it is immediately subordinate to the romance structure, for as soon as the barber is dead, Aunt Shadie and Rebecca look at each other for the first time. This is the moment the audience has been waiting for through the whole play, the answer to Aunt Shadie’s first word, "Re-becca..." (9), and the gaze is a long one: "as REBECCA and her mother stare at each other," the other women "take the razor, wash it and replace it," symbolically restoring order (126). Immediately afterwards Rebecca hands each of the women her braid, giving back the identity the barber took from them. "THE WOMEN leave in a line. Her mother remains standing. REBECCA reaches in her pocket and hands her mother her braid of hair" (126). Aunt Shadie calls her daughter by name—"Re-becca"—and touches her face. Rebecca thanks her in Cree and in English, before Aunt Shadie turns to follow the other women off. This mutual recognition, a kind of blessing, is clearly, we understand, regenerative and liberating for both: Rebecca watches the women with "their long, long hair spilling everywhere," sit down to a "beautiful banquet à la the Last Supper" (126). A legend projected from a slide tells us that this is "THE FIRST SUPPER–NOT TO BE CONFUSED WITH THE LAST SUPPER." Like the Last Supper, this is an image of communion, but it is a beginning, not an ending. Rebecca exits from the barbershop, walking we are told, "in the wind and the trees"—that is, in freedom (126). Northrop Frye observes that in romance the "world of the final festival is a world where reality is what is created by human desire" (Natural Perspective 115). "It is the world symbolized by nature’s power of renewal; it is the world we want; it is the world we hope our gods would want for us if they were worth worshiping." (116). In Clements’s play, in contrast to most romances in the Western tradition, it is also particularly and specifically a world created by a mother’s desire.

Gloria May Eshkibok, Michelle Latimer, Sarah Podemski, Deborah Allison, Lena Recollet, Gail Maurice, Michaela Washburn, J Patricia Collins, Muriel Miguel, and Valerie Buhagiar enjoy "THE FIRST SUPPER—NOT TO BE CONFUSED WITH THE LAST SUPPER" in the Native Earth Performing Arts production of The Unnatural and [r.sc]ccidental Women, Toronto. Nov. 2004.

Display large image of Figure 1

19 By re-scripting the revenge plot to allow the protagonist’s (or protagonists’) empowerment rather than punishment, does Marie Clements irresponsibly encourage her audience to take the law into their own hands? Is she implicitly advocating vigilante justice? I do not think so. I think what she offers is a kind of therapeutic fantasy: a way of managing grief. In Michelle La Flamme’s words, the play "provide[s] a healing ritual for the audience members through [...] commemorative acts that are based on [...] the act of witnessing and the power of naming." I argue further that this offers us, like the romance tradition which it transforms, a vision of an ideal world symbolized in "the first supper" that concludes the play; one that is as good as the Skid Row world of Act 1 is bad. This therapy would perhaps have been especially relevant for the Vancouver audience and actors in its first production, but its healing power is certainly not limited to that production. It is there for readers of the text as well. The Unnatural and Accidental Women allows its audience the opportunity to recognize not only injustice and racism, violence and loss, but also to recognize the agency of the murdered women, and to consider the possibility of a world created by maternal desire, where sisterhood triumphs over isolation and grief.

Works Cited

Aeschylus. Agamemnon. Trans. Richmond Lattimore. Grene and Lattimore 33-90.

— . The Eumenides. Trans. Richmond Lattimore. Grene and Lattimore 133-71.

— . The Libation Bearers. Trans. Richmond Lattimore. Grene and Lattimore 90-131.

Allan, William. Euripides: Medea. London: Duckworth, 2002.

Allman, Eileen. Jacobean Revenge Tragedy and the Politics of Virtue. Newark: U of Delaware P, 1999.

Aristotle. The Poetics. Aristotle’s Theory of Poetry and Fine Art. Ed. S. M. Butcher. 4th ed. New York: Dover, 1951.

Beaumont, Francis, and John Fletcher. "The Maid’s Tragedy." Ed. R. K. Turner. The Dramatic Works in the Beaumont and Fletcher Canon. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1970. 1-166.

Beer, Gillian. The Romance. London: Methuen, 1970. The Critical Idiom 10.

Birnie, Peter. Rev. of "The Unnatural and Accidental Women." Vancouver Sun 2 Nov. 2000, final ed.: C21.

Blondell, Ruby, et al. eds. Women on the Edge: Four Plays by Euripides. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Blondell, Ruby. Introduction to "Medea." Blondell, et al. 149-69.

Bowers, Fredson Thayer. Elizabethan Revenge Tragedy 1587-1642. Gloucester: Peter Smith, 1959.

Burnett, Anne Pippin. Catastrophe Survived: Euripides’ Plays of Mixed Reversal. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1971.

— . Revenge in Attic and Later Tragedy. Berkeley: U of California P, 1998.

Carson, Anne. Preface. "Hekabe." Carson, Grief Lessons. 89-97.

—, trans. Grief Lessons: Four Plays By Euripides. New York: NY Review of Books, 2006.

"Catskin." Cinderella in America: A Book of Folk and Fairy Tales. Ed. William Bernard McCarthy. Jackson: U P of Missippi, 2007. 4-42.

Clements, Marie. The Unnatural and Accidental Women. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005.

Cox, Marian Roalfe. Cinderella. London: Folklore Society, 1893.

"De Little Fox." The Penguin Book of English Folk Tales. Ed. Neil Philip. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1992. 86-90.

Dundes, Alan. "‘To Love My Father All’: A Psycholanalytic Study of the Folktale Source of King Lear." Cinderella: A Folklore Casebook. Ed. Alan Dundes. New York: Garland, 1982. 229-44.

Euripides. "Hekabe." Carson, Grief Lessons. 101-59.

— . Medea. Trans. Ruby Blondell. Blondel, et. al. 149-215.

Foley, Helene. Female Acts in Greek Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2001.

Fuchs, Barbara. Romance. New York: Routledge, 2004. The New Critical Idiom.

Frye, Northrop. A Natural Perspective: The Development of Shakespearean Comedy and Romance. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1965.

— . The Secular Scripture: A Study of the Structure of Romance. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1976.

Gilbert, Reid. "Marie Clements’s The Unnatural and Accidental Women: ‘Denaturalizing’ Genre." Theatre Research in Canada/Recherches théâtrales au Canada 24 (2003): 125-46.

Goldberg, Christine. "The Donkey Skin Folktale Cycle (AT 510B)." The Journal of American Folklore 110 (435): 28-46.

Grene, David, and Richmond Lattimore, eds. The Complete Greek Tragedies. Vol. 1. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992.

Hallett, Charles A., and Elaine S. Hallett. The Revenger’s Madness. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1980.

Haugo, Ann. "Decolonizing Motherhood: Images of Mothering in First Nations Theatre." Performing Motherhood workshop. Mount Allison U, Sackville, NB. Oct. 2008.

Hawthorn, Tom. "Gilbert Paul Jordan, the ‘Boozing Barber’: 1931-2006." Globe and Mail 8 Aug. 2007, natl. ed.: S7.

Haynes, Katherine. Fashioning the Feminine in the Greek Novel. London: Routledge, 2003.

Heliodorus. [Ethiopica.] An Ethiopian Romance. Trans. Moses Hadas. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1957.

Heiserman, Arthur. The Novel Before the Novel. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1977.

Kortekaas, G. A. A., ed. Historia Apollonii Regis Tyri. Groningen: Bouma, 1984.

Kyd, Thomas. The Spanish Tragedy. Ed. Philip Edwards. London: Methuen, 1959. Revels Plays.

La Flamme, Michelle. "Theatrical Medicine: Aboriginal Performance, Ritual and Commemoration." The Medicine Project. Prod. Glenn Alteen. 19 Aug. 2008. <http://themedicineproject.com/michelle-laflamme.html>.

McDermott, Emily A. Euripides’ Medea: The Incarnation of Disorder. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State UP, 1989.

McCulloch, Sandra. "Women, drink send killer to jail." Times-Colonist [Victoria] 9 August 2002, final ed.: B2.

McClure, Laura. Spoken Like a Woman: Speech and Gender in Athenian Drama. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1999.

McHardy, Fiona. Revenge in Athenian Culture. London: Duckworth, 2008.

Mojica, Monique, and Ric Knowles, eds. Staging Coyote’s Dream: An Anthology of First Nations Drama in English. Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 2002.

Mossman, Judith. Wild Justice: A Study of Euripides’ Hecuba. Oxford: Clarendon, 1995.

Nussbaum, Martha. The Fragility of Goodness. New York: Cambrige UP, 1986.

Pedrosa, José Manuel. "Comer con sal, comer sin sal, o lo civilizado frente a lo salvaje: el cuento ATU 923 (El amor como la sal) y otras fábulas de princesas desterradas y recuperadas." Culturas Populares. Revista Electrónica 4 (2007). <http://www.culturaspopulares.org/textos4/articulos/penadiaz.pdf>

Philip, Neil, ed. The Cinderella Story. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.

"The Princess in the Suit of Leather." Arab Folktales. Ed. Inea Bushnaq. New York: Pantheon, 1986. 193-200.

Rabillard, Sheila. "‘Being in a memory but present in time’: Re-inscription of Multiple Memories in Marie Clements’ The Unnatural and Accidental Women." Signatures of the Past: Cultural Memory in Contemporary Anglophone North American Drama. Ed. Marc Maufort and Caroline De Wagter. Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2008. 197-207.

Reardon, Bryan P. The Form of Greek Romance. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1991.

Rehm, Rush. Greek Tragic Theatre. London: Routledge, 1992.

Rose, Chris, Kim Pemberton, and Robert Sarti. "Bodies in the Barber Shop." Vancouver Sun 22 Oct. 1988, 3rd ed.: A12.

Sawchuck, Lee. "Hegelian Recognition in Euripides’ Medea." Unpublished paper presented at the conference on "Recognition from Antiquity to the Post-Modern and Beyond," Victoria College, University of Toronto, April, 2008.

Schotz, Myra Glazer. "The Great Unwritten Story: Mothers and Daughters in Shakespeare." The Lost Tradition: Mothers and Daughters in Literature. Ed. Cathy N. Davidson and E.M. Broner. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1980. 44-54.

Shakespeare, William. The Norton Shakespeare. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, et al. New York: Norton, 1997.

"The True Chronicle Historie of King Leir." Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare. Ed. Geoffrey Bullough. Vol. 7. London: Routledge, 1973. 337-402.

Thompson, Stith. Motif Index of Folk Literature. 6 vols. Rev. ed. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP, 1955-58.

Uther, Hans-Jörg. "The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Part I: Animal Tales, Tales of Magic, Religious Tales, and Realistic Tales, with an Introduction." FF Communications 284 (2004): 293-6, 555-7.

Winnington-Ingram, R. P. Studies in Aeschylus. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1983.

Wohl, Victoria. Intimate Commerce: Exchange, Gender, and Subjectivity in Greek Tragedy. Austin: U of Texas P, 1998.

Young, Alan R. "The Written and Oral Sources of King Lear and the Problem of Justice in the Play." Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 15.2 (1975): 309-19.

Notes