Articles

Age of Iron:

Adaptation and the Matter of Troy in Clements’s Indigenous Urban Drama

Sheila RabillardUniversity of Victoria

Abstract

In Age of Iron, Clements freely adapts Euripides’s Trojan Women. In Hutcheon’s terms, she "indigenizes," drawing on the ancient play selectively and localizing it. Her localization is unusual because she creates a double setting and a palimpsest of Trojan and Indigenous referents. The action occurs in a place which is both contemporary Vancouver and ancient Troy; the fall of Troy is also the conquest of BC’s Aboriginal peoples. This duality allows Clements to lament historical suffering even as she insists that conquest is happening now on the streets of Vancouver. The superimposition of different frames of reference politicizes the gesture of adaptation: Clements’s transformative art implies that past patterns of oppression can be re-shaped. Yet adaptation of a classical text is an ironic gesture, given that the play stages the destructive imposition of European culture. The layered ironies of the play derive, as well, from Clements’s appropriation of the "matter of Troy." Exposing the instability of national mythologies, she rejects the mythic descent of Britons from exiled Trojans, and claims Troy for her Aboriginal-identified characters. She revises British triumphalism, and instead of prophesying Troy reborn uses setting, set, and performance to dramatize the exilic present of "Trojans" in their homeland.Résumé

Dans sa pièce Age of Iron, Clements s’inspire librement des Troyennes d’Euripide. Pour citer Hutcheon, elle «. indigénise. » la pièce, en s’en inspirant sélectivement et en la localisant. Le procédé de localisation qu’elle emploie est inhabituel puisque Clements crée un double espace et un palimpseste de référents troyens et indigènes. L’action se déroule dans un lieu qui est à la fois le Vancouver d’aujourd’hui et l’ancienne Troie; la chute de Troie, c’est aussi la conquête des peuples autochtones de la Colombie-Britannique. Cette dualité permet à Clements d’évoquer la souffrance historique alors même qu’elle insiste sur le fait que la conquête se déroule aujourd’hui dans les rues de Vancouver. La surim-position de cadres de référence fait de cette adaptation un geste politique.: l’art de transformation pratiqué par Clements laisse entendre qu’on peut remodeler les anciennes formes d’oppression. Pourtant, adapter ce texte classique, c’est poser un geste empreint d’ironie.: la pièce met en scène l’imposition destructive de la culture européenne. Les multiples niveaux d’ironie de la pièce découlent aussi de l’appropriation que fait Clements de l’«.affaire de Troie.». Exposant l’instabilité des mythologies nationales, elle rejette l’origine mythique des Britanniques, supposés descendants de Troyens exilés, et réclame Troie pour ses personnages identifiés comme étant Autochtones. Elle revoit le triomphe britannique et, plutôt que de prophétiser sur la renaissance de Troie, elle se sert du lieu, du décor et du jeu pour donner une forme dramatique à la présence exilique des Troyens dans leur patrie.of the fifth generation

of men, but had died before it came,

or been born afterward.

For here now is the age of iron.1 (Hesiod, lines 174-180)

WISEGUY:

The discovery of the first metals and first attempt at civilization thus the earth arose from her confusion. (SFX: Sound of rain) Water from her terror, air from the consolidation of her grief, while fire was essential in all these elements as our ignorance lay concealed in these three suffering in the contemporary age, our Age… the Age of Iron. (Clements, Age of Iron 198)

1 Age of Iron was the first full-length play by Marie Clements to reach the stage. It was produced at Vancouver’s Firehall Arts Centre in October, 1994 and recently published in the collection DraMétis (2001). In many ways this drama anticipates strategies of Clements’s later work, in particular her use of complex, layered imagery.2 She creates a poetry of the stage—sight, sound, gesture—and an inter-textual, inter-cultural poetry of literary, historic, and political allusion. As Reid Gilbert has argued, Age of Iron operates simultaneously in more than one cultural system, "writing text at the intersection of discourses with quite different political and historical markers" ("Shine" 24) and by design frustrates a simple or settled response.3 Given its complexity, there are many possible approaches to this drama which addresses different potential audiences in different ways. I will focus on Clements’s adaptation of Trojan Women by Euripides and the implications of her taking up the matter of Troy. "Adaptation," here, is highly selective and inventive. While some lines closely echo those of Euripides, Clements focuses on the assignment of Cassandra as a war captive (though not her prophecy concerning Agamemnon); includes a version of the death of Astyanax; omits all of the action concerning Helen; weaves these Euripidean elements into material drawn from Indigenous history and contemporary experience; and transforms Euripides’s chorus of Trojan women into four groups: the System Chorus, the Sister Chorus, Apollo’s Muses, and the Wall of Troy (composed of dancers/singers and some of the named characters). As will become clear, the function of the chorus is adapted as well, for while the Wall and the Sister Chorus are identified with the conquered Trojans, the System and Muse choruses are associated with the conquerors. By using the phrase "the matter of Troy," I want to keep in mind not just characters and actions belonging to the story of the Trojan War and its aftermath in the Iliad and the Odyssey,4 but also the subsequent literary elaborations (continuing for many centuries after Euripides took up the subject) which allowed European cities and countries to trace legendary descent from Troy.5

2 Clements has said that she began to write this play, during a tour of northern Ontario, out of "a serious desire to understand and integrate the elemental connections between Greek mythology and Native thought" (Gilbert, "Profile" 148).6 Clements links ancient Troy; the history of the material, political, and cultural dispossession of the Indigenous people of North America; and contemporary Vancouver in a meditation on conflict, oppression, and survival. She adapts what Nicole Loraux has called the mourning voice of ancient Greek tragedy (Mourning 1)7 and the strategy of using "Trojan" characters allows Clements, who claims Metis ancestry, to suggest shared aspects of the experiences of Metis, status, and non-status Indigenous peoples. At times, the play presents details specific to a locality or culture (Whistler Mountain, trickster as Raven); at other junctures it refers to experiences potentially common to many Aboriginal-identified people: residential schools, unjust treatment of war veterans, and systemic discrimination by police, judiciary, and health services.8 Further, in staging the streets of Vancouver as simultaneously those of ancient Ilium,9 Clements takes a place in the succession of writers who through the ages have claimed the story of Troy in order to narrate their own nations. As Homi Bhabha argues, there is a precarious "split" between continuist and recursive temporalities in the production of a nation as narration. Noting the unaccommodated presence of marginalized or unassimilated people in the modern state, Bhabha asserts as well that "the conceptual ambivalence of modern society becomes the site of writing the nation" (145-146). Drawing on this analysis, I suggest that Clements exploits the instabilities Bhabha identifies. She narrates First Nations through the matter of Troy in a way that is multivalent, self-reflexive, and in a sense strategically divided against itself. She invites attention to the narration of nationhood as precarious, historicized gesture; she mourns painful divisions within First Nations dislocated from their cultures; and she disturbs Canadian national narratives.10

I. The Matter of Troy

3 On the largest scale, the play presents a series of analogies between the story of the fall of Troy, the history of the colonization and subjugation of Indigenous people in North America, and events in the lives of a present-day ad hoc "street family" (214) of Indigenous and marginalized people in a rough area of Vancouver during a brief span of time. This dramatic meditation is informed by awareness of the cultural uses both of stories and of their telling. The stage directions at the opening of Act One state that the performance should beThe annual re-telling of a legend, a story. Not a new story but one known to all and re-enacted in an Urban Troy Drama. The characters regard this as a custom, a sureness of movement, a festival, a showing off of dance and song, an unfolding of a great drama. (197)In other words, Clements deliberately takes up the matter of Troy and her presentation of it in the manner of a "re-telling," as a story "re-enacted," and suggests that she is pointing out some ironies as well as drawing upon Native traditions of story-telling and performance ("a sureness of movement, a festival, a showing off of dance and song, an unfolding of a great drama"). For the story of the fall of Troy becomes in the Aeneid the story of the origin of Rome and its empire, and the tale is taken up again by writers such as Geoffrey of Monmouth who makes the Trojan Brutus into the founder of Britain.

4 According to Virgil, Aeneas fled his conquered homeland, the city of Troy in flames, and eventually reached the shores of what is now Italy where, in turn, he conquered the local inhabitants and established the line whose descendents would found Rome. In Geoffrey’s twelfth-century History of the Kings of Britain, Aeneas’s great-grandson, Brutus, joins forces with enslaved Trojans in Greece, leads them in a successful fight for freedom, and then on a series of military adventures culminating in the settlement of an island, Albion. He re-names the island "Britain" from his own name and builds London as "New Troy."11 The Trojan story of a people conquered and a city destroyed has been used in the past, then, to establish an identity for states that became centres of power12 and then fell from power themselves.13 Notably, Geoffrey begins his story with a proleptic reference to the waves of successive conquest that would overcome Britain in the years between its foundation and his narration:Lastly, Britain is inhabited by five races of people, the Norman-French, the Britons, the Saxons, the Picts and the Scots. Of these the Britons once occupied the land from sea to sea, before the others came. Then the vengeance of God overtook them because of their arrogance and they submitted to the Picts and the Saxons. It now remains for me to tell how they came, and from where, and this will be made clear in what follows. (54)A drama which prompts its audience to consider re-tellings of Troy’s story invites contemplation of uncertainties, ambivalences. The fall of Troy is at once a story of making and of unmaking nations, a narrative of identity in which, paradoxically, Trojans become Romans, and then Britons. Framed by dance and by performance designed to show the story-telling art of the characters as well as the performers (i.e. by orature), Clements’s play implicitly critiques the supposed stability of the written as it explicitly critiques the compulsory schooling which imposed the textual "truths" of the conquering culture.

5 Clements plays upon the ambiguities of the historical transformations of the Trojan material, then, as well as the instabilities inherent in narrating a nation. Layering Trojan and Indigenous frames of reference, but never quite collapsing them into identity, she invites attention to contending histories and to what is at stake in their telling. There is an ironic wit in her artistic appropriation of the matter of Troy, a mythic history formerly used by the very nation that colonized British Columbia and its Indigenous peoples. In Clements’s re-telling, the colonizers, who are the supposed descendants of Trojan Brutus,14 by reversal, are turned into the invading Greeks who have just conquered Troy.15 That is, the "System chorus"—"the voices of social, law, and governmental bodies" (195) who represent the dominant (white) culture in contemporary Vancouver—are shown as threats to the First Nations characters who are identified in the cast list as also Trojans ("Wiseguy: Veteran Trojan Street Warrior / Elder" 194). Correspondingly, a member of the "System Chorus" is "Detective Agamemnon," a name that identifies him as one of the Greek leaders who conquered Troy. The "British" of British Columbia are thus doubly displaced: figured as intruders (in the city of Troy and, by implication, Vancouver) and no longer the central subjects of the mythic history of the Trojans’ fate, the heirs to reborn Troy. Although Canada’s national mythology does not include the matter of Troy, the structure of a dominant culture claiming origins in a history of displacement and dispossession finds parallels in the stories a settler nation tells about its immigrant past.

6 Clements takes the long view of history—the view from Olympus, one might say, which in this play is compared to the view from Whistler (218)—suggesting through the act of re-telling itself and the connection of Native and Trojan histories that a sense of potential, an assertion of collective strength, can be wrested from the sorrowful tale of Troy’s fall and appropriated to a Native context.16 As in Euripides’s tragedy, the opening action of the play situates the First Nations/Trojan characters at a point when they have been conquered and the invaders seem able to determine their futures: after the fall of Troy, assigning captives to servitude under various Greek leaders; in contemporary Vancouver, exerting both hard and soft control as cops, judges, social workers, medical personnel in a psychiatric hospital:COP. The assignment has been made, if that is your dread. They have been assigned to different masters.

WISEGUY. Is there good luck ahead for any of Troy’s children?

COP. I can tell you, but you must particularize your questions.

WISEGUY. Alright then. Who will get poor Cassandra?

COP. Detective Agamemnon took her as a special… eh…case. (228)

Here, as elsewhere

in the play, the different cultural and temporal frames of reference are layered, neither given precedence: Cassandra, as in Euripides’s tragedy, is allotted to Agamemnon who will be her "master" and also taken by Detective Agamemnon as a "special…eh…case"—a woman living on the streets, a prostitute, prone to prophetic raving. (The ambiguity of "took her" combined with the suggestive pauses in the phrase "special…eh…case" imply that the forced marriage to Agamemnon which awaits Cassandra in Trojan Women has an analogy in the contemporary action as her sexuality is exploited and policed by various representatives of the System.) The very similar exchange in Euripides reads:TALTHYBIUS. [a messenger of the Greeks]: You have now been assigned by lot to your masters, if that is what you were afraid of.

HECUBA. Ah me! What city of Phthia or of Cadmus’ land do you mean?

TALTHYBIUS. You are each assigned to a different man, not all together.

HECUBA. Then who has been assigned to whom? Who of the women of Troy has blessedness awaiting her?

TALTHYBIUS. I know the answers. But ask particulars, not everything at once.

HECUBA. Tell me, who has won my daughter, Cassandra the unblest?

TALTHYBIUS. King Agamemnon took her as his special prize. (Trojan Women, lines 240-249)

Yet as the ancient and more recent sorrows reinforce one another, suggesting not the inevitability of conquest but certainly its lamentable iteration throughout history, past uses of the matter of Troy imply a rise will follow the fall of Clements’s Trojans. Instead of a spatial journey from Troy destroyed to a new land and a Troy reborn, as in the stories of Aeneas and Brutus, the play gives us images from different points in time—suggesting a temporal journey—and interlaces them in one-and-the-same space to create a figurative dislocation. The characters belong to both ancient Greek legend and the history of our time, the audience cannot quite "fix" them in either setting, and the continual slippage between ancient and contemporary suggests as well that the characters themselves may experience an uncertain location in culture. By the close of the final act, we gather the force of Wiseguy’s statement: "Exiled, we survived in our homeland [...]. We are here, we are not gone for good" (271). The "exile" of Indigenous peoples in Canada has been an experience of political, economic, and cultural conquest rather than the geographic diaspora of the Trojans: a dispossession from power and cultural knowledge, while still present in the same homeland. Within the context of the myths of Troy, Wiseguy thus asserts the particular nature of First Nations exile: "We are here", and promises a (figurative) return: "we are not gone for good."

II. Adaptation

7 If this play can be seen as an intervention in the matter of Troy, it can also be regarded more specifically as an adaptation of Euripides’s Trojan Women. As I have shown, Clements takes the initial setting and action of her drama from Euripides and echoes some of his language.17 In discussing Clements’s play as adaptation, however, I do not mean to give superior value to the classical text, nor claim universality for Greek tragedy. As Linda Hutcheon argues, time itself changes the meaning of a canonical text because the circumstances of reception are altered (145);18 and where a text has been repeatedly adapted (as is the case with Trojan Women),19 the multiply-authored, historically developing tangle of versions penned by many hands might be thought of as a "discourse" (154), which is itself altered by each new addition. In the spectrum of adaptive interventions Hutcheon describes, Clements’s belongs to the most free, selective, and localizing kind, a transformation of a previous work across time and culture in a new context that produces something new. "People pick and choose what they want to transplant to their own soil. Adapters of traveling stories exert power over what they adapt" Hutcheon argues, and adapt what they take to "a usable form for a particular place or context" (150).20 I want to focus, then, on Clements’s very particular and located choices.

8 Ric Knowles’s analysis of adaptation as a strategy that allows The Death of a Chief to present material too painful to treat directly informs my consideration of the uses Clements finds for a canonical author, uses both analogous to those Knowles discusses and distinctly her own.21 Further, I argue that Clements draws attention to her adaptive gesture in part to evoke the difficult history of Native and European cultural interaction.

9 Clements’s title signals that her play is more than a commentary upon, or reaction to, Trojan Women. Age of Iron draws attention to temporality—an element of the Greek tragedy, though Clements makes the theme more prominent and develops a striking temporal structure. The ancient tragedian focuses his play on a suspended moment immediately after the Greeks have taken the city. In this moment between the glorious past and the uncertain future of Troy, the Greeks take steps to prevent a resurgence of the Trojans (dispersing captives, killing Hector’s son), and (in elements Clements omits) Trojans speak of the future awaiting certain Greeks (Hecuba arguing for Helen’s execution and Cassandra foretelling Agamemnon’s fate). In a sense, then, Euripides folds into the dramatized moment a struggle over the future. I have argued that Clements seizes upon the promise inherent in the "matter of Troy." She also makes Euripides’s theme of a contested future her own, particularly when she shows members of the System Chorus engaged in policing the Trojan inhabitants of the street. But her layering of time-frames creates an effect peculiar to her own purposes. Because there are two simultaneous temporal settings in her play—both ancient Troy and contemporary Vancouver—it is as if we are always at an historic moment when the future is being determined. This doubled time—the time of adaptation—suggests both that the past controls the future (as the contemporary characters echo words and actions from the ancient past) and that the present moment is a crucial decision-point for creating the future (for it doubles the past moment of determination). The hope of Troy rebuilt becomes less a foretelling than a present challenge to act, and the very freedom of Clements’s adaptation signals that both the literary and the historical past can be recast in order to find a way forward. In this respect, the instability of national narratives is turned to advantage.

10 Clements does not revise the matter of Troy into an unambiguous national myth of her own. Her insistence that the play’s characters are two things at once—always both Trojan and Indigenous, as Gilbert has noted ("Shine" 24, 28-31)—implies that the tale of Troy is a device, a strategy for the occasion, a way of speaking rather than a defining myth which elides internal inconsistencies and supposes a singular nationhood. In this highly reflexive play, hope, or futurity—necessarily problematic— lies in the power of the authorial gesture itself: in Clements finding a way to acknowledge the weight of past suffering without conceding strength, turning a tale of the dominant culture against itself, demanding a present response.

11 Clements adds further temporal complexity and political urgency by transforming the single act of Euripides’s play into two acts, incorporating in the second a flash-back to the childhood of Cassandra. Within the double time-frame Clements has established, this movement backwards in time from the contemporary scene has great power. It is frightening because it suggests that Clements is taking the audience back towards the traumatic history of European invasion and subjection of the Indigenous people of North America, events otherwise dealt with indirectly through the ancient conquest of Troy. And as the play moves closer to conquest temporally, so the events dramatized—experiences in the residential school system—are linked to it thematically, with the implication that such systems were (and are) conquest also.22 Because this flashback occurs in the second act, following a first act that evoked the assignment of Trojan captives to Greek generals, it reads in some respects as a consequence of those events, suggesting a parallel between Greeks taking Trojans into servitude far from home and the Canadian government taking children from their families and exiling them in the residential schools where language, religion, and culture were foreign.

12 Clements, then, explodes the lyric moment of Trojan Women and does so in order to politicize its grief. The simultaneously ancient and contemporary setting presents contact as conquest, and conquest as ever-recurring. The shift of focus from single event to historic and present-day process is particularly evident in her revision of the chorus. Clements follows Euripides in creating a chorus of women who lament their fate and the fate of their people; this is "The Sister Chorus." Yet even here there are crucial differences. Euripides presents a chorus of Trojan captives, but members of "The Sister Chorus" (while they evoke the prisoners of the ancient conquest) lament contemporary modes of subjugation. These "sisters of the streets" (194) sing of abuses they have suffered because they have been identified with what the dominant society rejects: "I am the one whom you have been ashamed of, and you have been shameless to me" (213). Further, the multiple functions of this chorus, combining Native and classical associations, suggest cultural assimilation as a form of conquest. The three earthly sisters, who belong to the Seven Sisters constellation, double as Apollo’s muses and thus are bound up with his myth and with his dramatized role in imposing schooling and religious instruction on Native children. Clements further revises Euripides by adding "The System Chorus," and her assignment of a collective function to representatives of the occupying forces underlines her concern to dramatize the dispersed—systemic— continuation of conquest.

13 As Clements makes the temporal structure of Trojan Women more dynamic and political, so, too, she transforms the action of the play. Age of Iron mourns—the single action of Euripides’s remarkable "oratorio" (Loraux 13). It also rages, and its acts of anger are directed both outward and inward. As in Euripides’s play, an important aspect of the action is the lamentation of mothers for dead children and their lost future. Hecuba, a "Trojan Street Warrior" who pushes a grocery cart of belongings, is also "Queen of Mothers," like her classical antecedent who was Queen of Troy, and mother of many children.HECUBA. I’ll tell you who I was and then you’ll pity me. I ruled a country once. My husband was king and all my sons were princes. I have seen them lying with whiteman’s spears through their hearts, and watched their father die. Now I must be a slave. My dress is torn, ragged and filthy. My whole body’s filthy. (205)

"What shall I do now?" she asks. The answer is that she must grieve: "I shall sing and cry

like a bird [...] when her nest is destroyed and her children" (206). It is significant, however, that Clements departs from Euripides in making mourning an action performed by both male and female characters; although Hecuba is the principle mourner, Wiseguy commiserates with her. This alteration disrupts the classical association between women and lamentation,23 insisting upon a whole community in sorrow. Further, Wiseguy’s designation as a "veteran" suggests that he is meant to bring to mind the discrimination Indigenous fighters met when they returned from war service and were denied veterans’ benefits.24 "A fighting man has no race, I thought" says Wiseguy. "When I came back half a man and more. I became even less in their eyes" (238). Wiseguy lives on the streets; he is clearly not honoured by the dominant society and at times is treated roughly by the police: "Cop raises his hand and places it over Wiseguy’s face, silencing him and pushing him back towards the Wall" (231). Though the military theme is hinted rather than developed fully, it acquires force because it is a reminder of yet another institution (like the residential schools) that has disserved Indigenous people. As Clements shows conquest to be an ongoing process, she also suggests the mourning which results is a reiterated action, with various specific topics of lament.

14 In adapting the mourning voice of ancient tragedy, Clements extends its range to compass rage. Clements gives her Hecuba a lament for a dead child which closely echoes lines spoken by Euripides’s Hecuba for her grandson Astyanax:25Oh dear mouth, you are gone, with all your pretty prattle. It was not true, what you used to say to me, climbing on my bed: "Mother, I’ll cut off from my hair a great big curl for you and I’ll bring crowds of my friends to your grave and give you fond farewells." (209)But Clements alters the plot of Euripides to disturbing effect. In the ancient tragedy, Astyanax is killed by the conquering Greeks because they fear that he might grow up to be a warrior like his father Hector. However, the lines of mourning spoken by Clements’s Hecuba are said over the broken body of a doll that she herself, along with Raven, just smashed. The contrast between adaptation and source intensifies the shock of witnessing an injured people turning their anger upon themselves. The subsequent action in the first act pursues the theme of suffering causing a reaction that further damages self and community. Clements shifts the dramatic focus from Hecuba to her daughter, Cassandra, and by shifting emphasis to a subsequent generation suggests the effects of extended suffering on a society and the transmission of its culture. Seemingly provoked by Cassandra’s prophetic ravings, Raven sexually assaults the prostitute/seer. Though in Euripides’s play Cassandra is raped by a Greek warrior and then assigned to another, here she is attacked by one of her own people who is also a figure from Native mythology—Raven is Trojan street warrior as well as trickster.

15 In her Act Two treatment of the Cassandra figure, Clements develops her fullest dramatization of suffering and resultant rage. In this Act, Clements moves beyond the situation delimited by Euripides’s play to stage events particular to the history of Indigenous people in Canada, specifically the abuses of the residential schools. Through Cassandra, Clements shows us that when the causes of anger are not acknowledged, or accusations are disbelieved, then rage and protest are misperceived as madness. The result is a seeming psychological conflict, an "inward" rage allied in its source, but distinct from, division sown between members of a damaged community.

16 Using elements of classical mythology Euripides omits,26 Clements establishes early in the play that Cassandra was made a seer by Apollo but that when she rejected his sexual advances he afflicted her with madness, condemned her prophecies to be disbelieved, and spat in her mouth (225-6). This image of violation assumes political force when Cassandra’s dream-flashback of Act Two takes us to a residential school. The figure of Apollo, who is also "a Christian priest of a residential school" (195), brings together religion, schooling, physical abuse, and a cursed gift. Clements thus establishes a pattern of tainted gifts: Cassandra’s prophetic utterance; the physical mistreatment and sexual abuse of First Nations children; and the ruin of familial bonds and cultural knowledge, resulting from the "gift" of mandatory, Eurocentric residential education. Apollo’s "Muse Chorus" (likewise absent from Euripides) underlines the ‘Trojan horse’ character of the church-run residential schools as they use "the beautiful choir music of Christianity to manipulate" (195).

17 In Cassandra’s flashback, Clements presents two institutional settings simultaneously: in the past, the school where Cassandra’s siblings, Eileen and Alfred, are imprisoned; and the present-day psychiatric hospital, where she is held by the "system" after she is attacked by Raven. Eileen and Alfred are separated, stage left and right, a separation that reflects the residential school practice of educating boys and girls apart, thus further isolating siblings already taken from their families. In her dream, Cassandra runs back and forth between them and her frantically divided attention reads both as distress and as madness (given the psychiatric setting). Thus the gestural language of the scene performs the transformation of rage into apparent insanity; without the figures of Eileen and Alfred one would see a self divided against itself.

18 Later in the Act, Clements revisits the relationship of Cassandra and Apollo, this time emphasizing not Apollo the god (who has at least some positive valence as an aspect of the divine), but the abusive priest. She presents the incomprehension and disbelief met by Cassandra’s prophetic utterances as the reaction of the judicial system confronted with the testimony of someone who claims to be a victim of rape by a residential school priest. The spokesperson of Apollo quietly insinuates that Cassandra must have misinterpreted the priest’s gesture: "I mean, did he have an affection for you. Surely it must have been an innocent concern for a child" (265). It’s a telling use of the classical Cassandra. In the ancient myth of a raving, disbelieved prophet, Clements finds a figure for the mad distress resulting from the psychological harm of such abuse and from the anguish of unheeded protest.

19 Clements revises Cassandra’s central prophetic function in Euripides. In the Greek tragedy, she foresees her part in the death of the Greek Agamemnon and the dreadful fate of his house. In contrast, Clements gives to Cassandra, who embodies so much of the history of damage done to indigenous culture, a challenging vision of hope. Cynical Raven complains that her prophecy is difficult to accept:She says the old Troy is inside us growing, waiting for the wakening moment… rising up from the ashes of the earth. Like our dead ancestors are rising up in us, that they’re actually in us, like the land is in us […]. So I’m left here with all these freakin’ images. Thanks bitch. (234)There is reason for Raven’s lasting cynicism, even for his shocking Act One attack on Cassandra: as we discover in the dream sequence, she once looked forward to what the residential school might offer and persuaded her younger brother and sister towards the same hope. This painful association—between hope and madness, hope and a history of betrayal—is made more painful still by the suggestion of fissures within the Native community; that is, the anger Raven directs against Cassandra hints at rage children may feel towards parents who were unable to prevent their removal to residential schools. And there is a self-reflexive irony built into the structure of this play which opens with an affirmation of the value of the traditional knowledge of Native culture: "If I do not understand how the fire came to be, I will burn in it because I will not know my own roots" (198) and offers a prophecy of Troy reborn as the product of the cursed gift of foresight to Cassandra from Apollo/residential school priest. Perhaps here is some ambivalence about the play itself and its adapted matter, about dislocations of meaning.

20 In the overall pattern of her play, Clements adapts Trojan Women by staging a transition from mourning to rebuilding community. Age of Iron begins with lamentation for the fall of Troy into the hands of the Greeks, which is also the fall of Indigenous people under the rule of European colonizers. This grief intensifies into anger both inwardly and outwardly directed at the climax of Act One; then this action is recapitulated in the much briefer Act Two, but with the crucial difference that by the end of the play the Indigenous/Trojan characters (with no "Greeks" on stage) are able to offer one another comfort, teaching, and mutual acceptance. Even Raven who has earlier attacked Cassandra (and is now reduced to plucking his own feathers) accepts her help:RAVEN. I have no song.

CASSANDRA. Let it come from you, ancient and new. It’s there rooted in you. You have a song. Sing it, so others might hear and know they are not alone, that we are all there in voices ancient and new, too many to be silenced.

RAVEN. Sing it, so others might know they are not alone. Sing it. (270)

21 Stage directions tell us that the movements of the characters near the end of the play turn into a lovelier kind of dance than we have seen before: "Either traditional and/or a mixture of Trojan warrior movements similar to prologue but less fierce and more beautiful, flowing" (272). The last words of the play are an invocation of the Moon, addressed respectfully and as a member of the family: "Grandmother Moon. Kiss us, please." The blood-red planet Mars, war god of the classical world—dominant at the opening of the play—and the shimmering, strangling, golden strands associated with Apollo (who is also the Christian god of institutional oppression and residential school abuses) have been replaced at the close by the sky and earth as defined by Indigenous culture. So it is Raven who speaks and to whom sky and earth respond:Final drum beat, music stops, movements stop.

RAVEN. How you doing, sky?

SISTERS. Fine, thank you.

RAVEN. How are you Mother today?

Earth Woman points at him.

RAVEN. Me? Just fine, thanks for asking.

WISEGUY. Grandmother Moon. Kiss us, please. (273)

Elsewhere in the play Clements uses doubled Trojan and Native frames of reference to evoke enforced cultural assimilation and disrupted Native heritage. Here, the drama moves towards its end by means of a shift in tone and strategy. Strength is drawn from mourning accomplished, classical imagery fades (although not completely, for it necessarily leaves memory traces upon the playing space and in the partly "Trojan" warrior movements of the dancers), and the transformed dramatic structure asserts Clements’s own culture and purposes.

22 A brief scene just preceding these closing lines recapitulates the play’s central action of mourning and transforms this action into an articulation of potential community. In this passage, Hecuba says farewell to her daughter Cassandra, speaking for her ears but addressing a doll, one of many she has carefully placed around her. This indirect communication suggests the sufferings of disrupted families: doll as prop distracting Hecuba’s gaze from Cassandra, doll as substitute for absent real child, doll as surrogate means of addressing what is difficult to confront. But Hecuba’s mediated speech also indicates an emotional and ethical investment extending beyond her offspring to community and kin broadly conceived. "(Cassandra goes to turn away. Hecuba talks intently to doll.) There is hope, isn’t there? If you love there is hope. Isn’t there? Never, never will I let you go. I see your eyes in others and know that you are here in numbers that need to be mothered" (271). As Hecuba declares "I will manage" (271) and "dotes on her [doll] children" (272) Clements creates a tenuous promise of Troy reborn not through further deeds of conquest but through mothering work. Hecuba: "There is no chance but life. Remember that. Now I know I stumble and fall on each tile of these streets, but at least I am upright some of the time. At least I AM still here fumbling with gravity" (271). It is important to note that this concluding articulation of hope is interrogative and conditional and that it is not spoken by Cassandra whose prophecies are so distressingly entangled with the curse of Apollo, and hence with the imposed narratives of alien schooling.

III. Adaptation as Location

23 What hope, then, that Troy will rise again? Clements uses the physical images of the stage space to make a claim on the urban terrain of Vancouver as Indigenous land. Though the Trojans are exiled from power they are still here. The famed wall of Troy is an ordinary wall bordering a street but, extraordinarily, it is made up of the living bodies of actors. Perhaps Clements’s most eloquent invention is this "structure." As the play begins, under the red glow of the planet Mars,Native drumming rises up and as it does it awakens movement from a great breathing city wall. As lights fade up the exterior of the wall is made up of street debris that begins to breathe as one and move slightly to the call of the drum. As the living wall awakens the sound of breath increases to form vocals that meet the drumming. As the sound increases the movement on the wall begins to clatter as the wall reveals human shapes of warriors dressed in iron street armour of shields and masks. Wiseguy emerges from the wall fierce and war-like. As Wiseguy talks, the wall comes alive. (197)The characters emerge from and return to the wall in the course of Act One, and their literal embodiment of a defining urban structure asserts vividly that they form a part of the social ecology of the city.

24 Further, Clements builds upon the bond between suffering mother Hecuba and the earth of her native land already strongly marked in Euripides’s play, where the opening dialogue of the gods takes place as the queen lies flat on her back, weighed to the earth by grief. Clements gives the earthy aspect of Hecuba’s grief an independent embodiment and much richer existence in the person of the Earth Mother who sleeps in a cement-covered concavity in the street and is brought to light when chunks of pavement are pulled away. Wiseguy tells the audience:You have only seen this land of Troy from the outside. The walls and floors are thick and grimy with the wars and plagues and now hardened. But inside it is a beautiful woman alive with happiness and living […] You envy that. You have no such land because you have covered it with an ungiving surface. (202)Key, then, to the play’s searing vision of the effects of human action, over the long span of history and in the immediate present, is its theatrical imagination which literally grounds its characters in the substance of their surroundings. Clements places us here, in Vancouver, in an "age of iron—a loss of way for all peoples. An age of war but also of transition, bravery, courage." (194) The close of the play, in a species of envoi, puts aside the past tense of myth and history and the future tense of prophecy to (re)present the present not reduced to significant mythic outline, but sprawling before us in all its uncertainties and contradictions. This present is enacted by dance and drumming, echoing the opening and emphasizing the performance itself. The present is announced in a quick succession of assertions by Sisters, Cassandra, and Hecuba, each beginning "I am," assertions which are summed up by Wiseguy in a paradox-filled speech suggesting both "loss of way" and "transition, bravery, courage": "We are the knowledge and ignorance. We are shame and boldness. We are shameless and we are ashamed. We are strength and we are fear. We are war and we are peace. Give heed to yourselves. We are all the disgraced and the great one" (273). Through the alien and indigenized imagery of Troy, Clements asserts a homeland which is also a place of exile. The tone at the close, I suggest, is not so much hopeful as challenging, and the final speech act, fittingly, is a prayer.

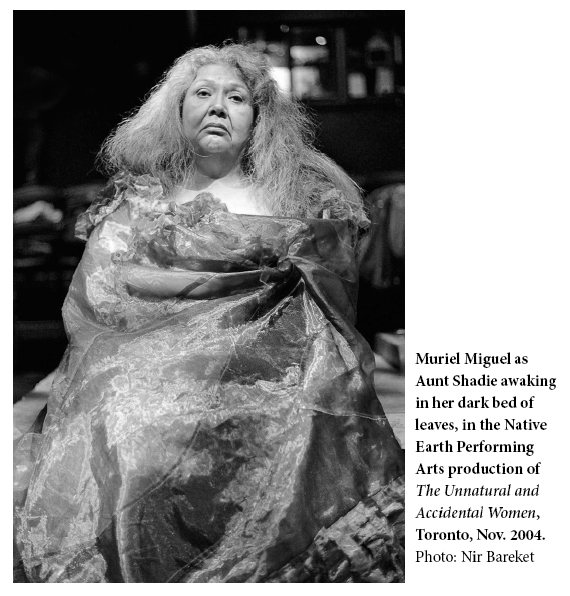

Muriel Miguel as Aunt Shadie awaking in her dark bed of leaves, in the Native Earth Performing Arts production of The Unnatural and Accidental Women, Toronto, Nov. 2004. Photo: Nir BareketWorks Cited

"Aboriginal Veterans: Essential Facts and Time Line." The War Amps. 2003. Newsroom. Web. 30 Jan. 2009. <http://www.waramps.ca/newsroom/archives/abvet/back.html>.

"Aboriginals and the Canadian Military." CBC.ca. 2006. CBC News in Depth. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. <http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/aboriginals/aboriginals-military.html>.

"Benefits Under the Veterans Charter Not Applicable for Most Métis or Treaty Indians." News Release from the National Council of Veterans Associations in Canada. 2002. Turtle Island. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. <http://www.turtleisland.org/news/veterans.pdf>.

Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. London and New York: Routledge, 1994.

Budelman, Felix. "Trojan Women in Yorubaland: Femi Osofian Women of Owu." Classics in Post-Colonial Worlds. Ed. Lorna Hardwick and Carol Gillespie. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 15-39.

Butler, Judith. The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1997.

Cheng, Anne Anlin. The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis, Assimilation, and Hidden Grief. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001.

Clements, Marie. "Age of Iron." DraMétis: Three Metis Plays. Ed. Greg Daniels, Marie Clements, and Margo Kane. Penticton, BC: Theytus, 2001. 193-273.

— . The Unnatural and Accidental Women. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005.

Eng, David L., and David Kazanjian, eds. Loss: The Politics of Mourning. Berkeley: U of California P, 2003.

Euripides. Trojan Women, Iphigenia Among the Taurians, Ion. Ed. and trans. David Kovacs. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1999.

Foley, Helene P. "Bad Women: Gender Politics in Late Twentieth-Century Performance and Revision of Greek Tragedy." Dionysus Since 69: Greek Tragedy at the Dawn of the Third Millennium. Ed. E. Hall, F. Macintosh, and A. Wrigley. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. 77-111.

Geoffrey of Monmouth. The History of the Kings of Britain. Trans. Lewis Thorpe. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966.

Gilbert, Reid. "Profile: Marie Clements." Baylor Journal of Theatre and Performance 4.1 (2007): 147-51.

— . "‘Shine on us, Grandmother Moon’: Coding in Canadian First Nations Drama." Theatre Research International 21.1 (1996): 24-32.

Goldhill, Simon. How to Stage Greek Tragedy Today. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007.

Grimal, Pierre. "Cassandra." The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Trans. A.R. Maxwell-Hyslop. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986.

Hardwick, Lorna, and Carol Gillespie, eds. Classics in Post-Colonial Worlds. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007.

"Heroes." The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. 2nd ed. 1989.

Hesiod. The Works and Days, Theogony, The Shield of Herakles. Trans. Richard Lattimore. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1959.

Highway, Tomson. Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing. Saskatoon, SK: Fifth House, 1989.

"Homer." The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. 2nd ed. 1989.

Howatson, M.C., ed. The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1989.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation. London and New York: Routledge, 2006.

"Indian Residential Schools." CBC.ca. 2009. CBC News. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. <http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2008/05/16/f-faqs-residential-schools.html>.

Indian Residential Schools Settlement. 2009. Official Court Website. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. <http://www.residentialschoolssettlement.ca/>.

Indian Residential Schools Resolution. 2009. Government of Canada. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. <http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/ai/rqpi/index-eng.asp>.

Indian Residential Schools Resolution. Report on Plans and Priorities. 2007. Treasury Board of Canada. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. <http://www.tbssct.gc.ca/rpp/0708/oirs-brqpa/oirs-brqpa-eng.asp>.

Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission. 2009. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. <http://www.trc-cvr.ca/indexen.html>.

Indian Residential Schools Unit. 2008. Assembly of First Nations. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. <http://www.afn.ca/residentialschools/history.html>.

Knowles, Ric. "The Death of a Chief: Watching for Adaptation; or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bard." Shakespeare Bulletin 25.3 (2007): 53-65.

Kuch, H. "Euripides und Melos." Mnemosyne 51 (1998): 147-53.

Loraux, Nicole. Mothers in Mourning. Trans. Corinne Pache. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1998.

— . The Mourning Voice: An Essay on Greek Tragedy. Trans. Elizabeth Rawlings. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2002.

Lycophron. "Alexandra." Trans. A.W. Mair. Callimachus, II, Hymns and Epigrams Lycophron: Alexandra Aratus: Phaenomena. Trans. A.W. Mair and G.R. Mair. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard UP, 1921.

Martin, Carol. "Lingering Heat and Local Global J Stuff." The Drama Review 50.1 (2006): 46-56.

McDonald, Marianne. Ancient Sun, Modern Light: Greek Drama on the Modern Stage. New York: Columbia UP, 1992.

— . "Rebel Women: Brendan Kennelly’s Versions of Irish Tragedy." New Hibernia Review 9.3 (2005): 123-36.

Mendelsohn, Daniel. Gender and the City in Euripides’ Political Plays. .Oxford: Oxford UP, 2002.

Ratsoy, Ginny, and James Hoffman, eds. Playing the Pacific Province: An Anthology of British Columbia Plays, 1967-2000. Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 2001.

Remembering the Children. 2009. The Anglican Church of Canada. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. <http//www.rememberingthechildren.ca/history/index.htm>.

Resolution 2007-12, "Aboriginal Veterans Compensation Package." 2007. Congress of Aboriginal Peoples. Web. 30 Jan. 2009. <http://www.abo-peoples.org/about/2007_Resolutions/2007-12.html>.

Resolution 2008-05, "Compensation for Aboriginal Veterans." 2008. Congress of Aboriginal Peoples. Web. 30 Jan. 2009. <http://www.abo-peoples.org/media/RESOLUTIONS2008revised.pdf>.

Sheffield, R. Scott. "A Search for Equity: A Study of the Treatment Accorded to First Nations Veterans and Dependents of the Second World War and the Korean Conflict." April 2001. Report for The National Round Table On First Nations Veterans’ Issues. Turtle Island. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. <http://www.turtleisland.org/news/veterans.pdf>.

Suzack, Cheryl. "On the Practical ‘Untidiness’ of ‘Always Indigenizing.’" English Studies in Canada 30.2 (2004): 1-3.

Thompson, Ruth. "Theatre/s of Peace and Protest: The Continuing Influence of Euripides’ Play The Trojan Women at the Nexus of Social Justice and Theatre Practice." Australasian Drama Studies 48 (2006): 177-88.

"Trojan War." The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. 2nd ed. 1989.

van Erp Tallmann Kip, A.M. "Euripides and Melos." Mnemosyne 40 (1987): 414-19.

"Veterans Group Asks That Payment for Aboriginal Veterans Not Be Delayed." The War Amps. 2009. Newsroom. Web. 30 Jan. 2009. <http://www.waramps.ca/newsroom/archives/abvet/2006-06-28.html>.

Žižeck, Slavoj. "Melancholy and the Act." Critical Inquiry 26.4 (2000): 657-81.

Notes