Articles

Theatrical Medicine:

Aboriginal Performance, Ritual and Commemoration (for Vanessa Lee Buckner)1

Michelle La FlammeUniversity of the Fraser Valley

Abstract

The paper begins by discussing some Aboriginal teachings offering the author’s working definition of Medicine based on the teachings that elders have shared. These cultural traditions reflect a belief in the power of performance and the possibility of performance as medicinal. The paper applies some of these teachings about Medicine to suggest that the form and experience of these theatrical events can be understood as contemporary good Medicine. These performances and plays by Aboriginal people bring balance to the witnesses through honouring the deceased by way of naming rituals, they bring balance to communities by showing the humanity of Aboriginal women, and they provide a cathartic ritual or ceremony for the release of trauma.Résumé

Cet article commence par présenter un certain nombre d’enseignements et de cérémonies de la tradition autochtone, pour ensuite proposer une définition de la médecine fondée sur les enseignements des Anciens. Ces traditions culturelles reflètent une croyance dans le pouvoir de la performance et dans ses possibilités médicinales. L’article étudie quelques enseignements sur la médecine et décèle dans la forme et l’expérience de ces événements théâtraux des propriétés médicinales contemporaines. Les performances et les pièces d’artistes autochtones contribuent au mieux-être des témoins qui rendent hommage aux femmes décédées par une lecture rituelle de leurs noms; elles contribuent au mieux-être des communautés en montrant l’humanité des femmes autochtones et elles fournissent un rituel ou une cérémonie cathartique qui permet d’évacuer le traumatisme.1 There are many different definitions of Medicine as unique and diverse as the peoples and cultures that create them. As a woman of mixed heritage (Metis, African-Canadian, and Creek) I consider myself fortunate to have been exposed to a diverse range of Aboriginal teachings and ceremonies. My own definition of Medicine has been distilled from the teachings of traditional elders who have shared their cultural insights with me regarding the power and meaning of Medicine.

2 There is Medicine involved in seeking advice from elders by way of offering them tobacco or other sacred medicinal plants or objects. There are Medicine Wheel ceremonies that involve respect for the four directions and the balance between the physical, mental, spiritual, and emotional aspects of an individual. There is Medicine in the practice of creating art whether that be carving, weaving, canning, beading, drum-making, or painting. Medicine can also be an active process that is understood in a psychological or philosophical way, whereby individuals go through a form of catharsis when they are guided by traditional teachings. There is participatory Medicine involved in being a witness or participant in ceremonies. There are physical forms of Medicine such as tobacco, sweet grass, sage, and cedar. Some traditional languages do not have a word for theatrical performance, so they use the closest word, which is ceremony. There is Medicine that is inherent in ceremony, whether these be sweat-lodge ceremonies, rites-of-passage ceremonies, moon-lodge ceremonies, naming ceremonies, or longhouse ceremonies, or certain traditional performances of dance or song.

3 These cultural traditions reflect a belief in the power of performance and the possibility of the performance being understood as ceremonial and potentially medicinal, for any or all of these cultural associations with Medicine. I want to apply some of these teachings about Medicine to suggest that the form and experience of four important Aboriginal theatrical events can be understood as contemporary good Medicine involving ceremonial and medicinal elements. The plays I examine are Annie Mae’s Movement by Yvette Nolan, The Unnatural and Accidental Women by Marie Clements, Archer Pechawis’s performance "Elegy," and Rebecca Belmore’s "Vigil." These Aboriginal performances and plays bring balance to the witnesses through honouring the deceased by way of naming rituals, they bring balance to communities by showing the humanity of Aboriginal women, and they provide a cathartic ritual or ceremony for the release of historical and racialized trauma.

4 In Yvette Nolan’s Annie Mae’s Movement, the main character, Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, is represented as one of the "disappeared" warriors in the struggle for Aboriginal empowerment. Nolan revises the historical account of Aquash in a way that suggests that "disappeared" women warriors will not be left on the margins of history. Marie Clements also tells a story of murdered Aboriginal women in her play The Unnatural and Accidental Women. These plays and two performances by Aboriginal performance artists Rebecca Belmore and Archer Pechawis provide important moments of collective grieving and medicinal witnessing for all Canadian audiences. I will start with a close reading of Nolan’s play, compare it with Clements’s play, and follow the thread of performance as Medicine through an examination of two examples of performance art which achieve many of the same goals. These Aboriginal artists have created work that inspires others and, simultaneously, transforms communal and national grief through the ritual of witnessing and naming in commemorative performance.2

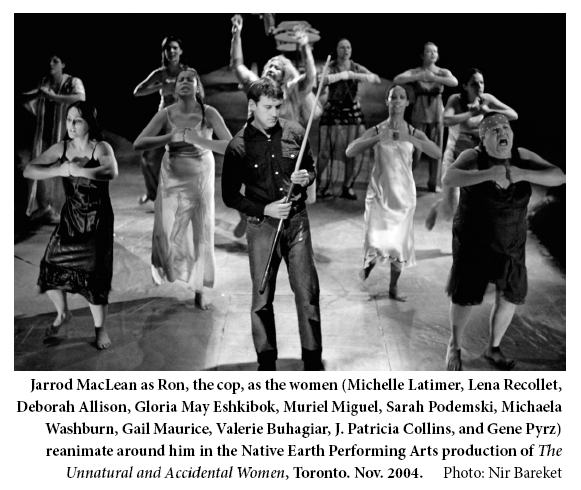

Jarrod MacLean as Ron, the cop, as the women (Michelle Latimer, Lena Recollet, Deborah Allison, Gloria May Eshkibok, Muriel Miguel, Sarah Podemski, Michael Washburn,.Gail Maurice, Valerie Buhagiar, J. Patricia Collins, and Gene Pyrz) reanimate around him in the Native Earth Performing Arts production of The Unnatural and Accidental Women, Toronto. Nov. 2004.

Display large image of Figure 1

5 The most infamous story of a murdered Aboriginal woman in Canadian history is the story of Annie Mae Pictou Aquash. A version of her story was brought to Canadian stages in Yvette Nolan’s play Annie Mae’s Movement. Nolan’s play was first presented as a staged reading at the Weesakechak Begins to Dance festival of new plays at Native Earth Performing Arts in Toronto, 17-22 February 1998, and premiered in Whitehorse, Yukon, 17 September 1998. Nolan’s play has been produced a number of times and most recently was staged as part of the 2006 Honouring Theatre event that offered a trilogy of plays by Aboriginal artists from Canada, Australia, and Samoa. It was produced again in October of 2007 at the Firehall Theatre in Vancouver. This play provides an interesting representation of Aquash that can be understood within this cultural context as medicinal.

6 In order to evaluate the impact of Nolan’s play as medicinal, we need to engage in a close examination of the ways in which she characterizes the central figure of Aquash. Whereas some playwrights address transnational and transhistoric feminist struggles, Nolan investigates feminist struggles within the American Indian Movement itself. Nolan delves into the patriarchy of the American Indian Movement by documenting the complex position Aquash occupied as a woman in the largely male-dominated

organization. Nolan’s Aquash offers her own perspective on her political views and feminist ideals in the opening monologue:ANNA. You gotta stand up, you gotta fight for what’s important, no matter who wants you to shut up. We have to fight, even if it seems like we’re fighting ourselves. Or else we will disappear, just disappear. (4)

Here the Aquash character in Nolan’s play is given an interiority and first-person perspective on the need to resist erasure within the organization itself. In this respect the play is emancipatory for women because it documents the culturally specific contours of patriarchal oppression within the American Indian movement and, by extension, other Aboriginal community contexts.

7 Besides this feminist impulse, Nolan chooses to have the character "Anna" re-enact her murder on stage. This scene both places the audience as witness to this murder and simultaneously allows the audience to express its grief over her murder. These two objectives are finely balanced in the staging of the story surrounding this important Canadian Aboriginal woman. In Annie Mae’s Movement, Nolan stages the murder after this prophetic speech:ANNA. My name is Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, Micmac nation from Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia. My mother is Mary Ellen Pictou, my father is Francis Thomas Levi, my sisters are Rebecca Julien and Mary Lafford, my brother is Francis. My daughters are Denise and Deborah. You cannot kill us all. You can kill me, but my sisters live, my daughters live. You cannot kill us all. My sisters live. Becky and Mary, Helen and Priscilla, Janet and Raven, Sylvia, Ellen, Pelajia, Agnes, Monica, Edie, Jessica, Gloria and Lisa and Muriel, Monique, Joy and Tina, Margo, Maria, Beatrice, Minnie, April, Colleen…

You can kill me, but you cannot kill us all. You can kill me. There is a gunshot. She falls, curls into a foetal position. Blackout. (41-42)

8 There are several aspects of Nolan’s choice that deserve attention here. By pairing this hopeful speech with the dramatic murdering of this character on stage, she implicates the audience as witness to this murder. Nolan structures this scene in this way to allow the audience members who are grieving the murder of many Aboriginal women, understood here as witnesses in a ceremony, to have some commemorative moments throughout the play. The importance of community and the bonds that exist in the seven generations of Aboriginal women are traditional elements in this play expressed through the power of naming. This naming ritual serves a larger communal purpose in that by naming family, friends, and Aboriginal playwrights and by claiming that "You can kill me, but you cannot kill us all" (42), the character suggests the powerful and enduring effect that Aquash’s actions have had, and will continue to have, on Aboriginal women. Thus these first two aspects—the role of the audience as witness and the naming of the deceased—have traditionally been powerful means to alleviate grief and validate the life of the deceased: lest we forget.

9 This scene also allows Nolan to suggest that the intergenerational effects of this woman warrior/martyr will inspire other Aboriginal women. The figure of Aquash becomes more than an individual in this moment in the play and she reminds the audience that the struggles are not over for Aboriginal women in this celebratory speech. Interestingly in Nolan’s play, Aquash is prophetic in that she has a first-person perspective on her existence before her staged death. This first-person perspective enables the actor and the audience to consider the possibility of Annie Mae’s conscious awareness of her role as a martyr for a larger cause. After an intense interrogation, when her death becomes inevitable, Aquash reflects on the power of women to bring about change and ruminates on the effect that her death will have on other activists. In addition, this final speech extends the life of Aquash beyond the point of her physical death and presents her quite clearly as a martyr.

10 There is yet another aspect to Nolan’s version of Aquash’s story that relates to its effect on Nolan as an Aboriginal woman. One might say that Nolan’s play documents her own refusal to accept the silencing of women. Seen in this light, Aquash’s death is a marker and political touchstone of feminist resistance in a way that provides both a defiant and a tragic example of some of the consequences of being an Aboriginal woman warrior.

11 The second contemporary Canadian play that can usefully be compared to Annie Mae’s Movement is Marie Clements’s The Unnatural and Accidental Women. The play was written in 1997 and a staged reading was given at the Vancouver East Cultural Centre in the same year. It premiered in 2000 at the Firehall Arts Centre in Vancouver and was first published in 2002. Clements’s play, like Annie Mae’s Movement, offers a vision of Aboriginal women whose influence extends beyond the point of death, and she also utilizes various aspects of ceremony in the theatrical Medicine she offers. Clements, like Nolan, has managed to write beyond the death of these Aboriginal women characters by employing specific narrative techniques. Both playwrights have also managed to provide a healing ritual for the audience members through these commemorative acts that are based on colonial trauma, the act of witnessing, and the power of naming. Although Clements’s play is not about Aquash, her drama does focus on the murder of Aboriginal women, and so it is this point that forms the basis of my comparison between the two plays.

12 In The Unnatural and Accidental Women, the tragedy of the women’s deaths is transformed by Clements’s use of a fictional revenge plot in which the murdered Aboriginal women, who appear as ghosts, execute the man who has murdered them. The "truth" about these murdered women is that the killer, Gilbert Paul Jordan, was only sentenced for one of the eleven murders, served six years, and was released. Although the basis of this play is factual, Clements takes creative license to extend the power of these murdered Aboriginal women to effect change beyond the grave by giving them an embodied and active presence as ghost murderers. I must point out here a crucial difference in staging. Unlike Nolan, Clements chooses not to represent the murder of an Aboriginal woman on stage, but, rather, closes her play with the murder of the killer by an Aboriginal woman. In both cases, the death scenes place the spectators in uncomfortable roles as witnesses to murder. However, by choosing to construct a play in which the murderer is killed on stage, Clements effectively rewrites the events in a way that empowers the Aboriginal women who were murdered.

13 Clements does not represent the murder of the women on stage; she chooses to focus on the last few hours of their lives before they were killed. Slide projections indicate that the women have been murdered; they document the "official" versions of the coroner’s reports that state that each woman died of "unnatural and accidental" causes. Only one murder is shown on stage, and that is the murder of the killer. In this respect, Clements’s vision is similar to Nolan’s in that the playwright, in each case, refuses to close the play with the horrific murder(s) of the Aboriginal women, while simultaneously finding a way to foreground the murder(s) in the performance.

14 Annie Mae’s Movement and The Unnatural and Accidental Women use the power of drama to document the lives of real and murdered Aboriginal women. In this respect, both plays commemorate these lives and, consequently, have the potential to heal communities. They are also postcolonial (and feminist) narratives that attempt to retell Aboriginal women’s stories from the fictionalized perspective of the women themselves. This single choice has larger historical implications. Because of these two plays, the hushed stories of these murdered Aboriginal women have been rescued from the margins of history. They are intrinsically emancipatory gestures by Clements and Nolan because the plays bring the lives of murdered Aboriginal women to the stage. In this respect, both plays function as memorials for the "disappeared" Aboriginal women in Canadian society and as "good Medicine" for Aboriginal audiences.

15 Other Canadian artists have more explicitly used performance as a means to create memorials for Aboriginal women who have been victims of violence in Canada. The following two artists use different means to rescue Aboriginal women’s lives from historical occlusion and obscurity. Their performances are raw and immediate because both artists ritualize the violence and implicate their own Aboriginal bodies and not just the audience in this horror. Both performances use the lighting of candles and a ritualized naming of the missing women as both performance art and elegy. Despite the different means and the different values attached to "theatre" and "performance art," Pechawis and Belmore, like Clements and Nolan, provide Medicine by way of performance.

16 Aboriginal performance artist Rebecca Belmore has created a performance art installation entitled "Vigil" that commemorates missing and murdered Aboriginal women in Vancouver.3 Belmore set her performance in an alley in the downtown Eastside where Aboriginal women’s bodies have been found. In the performance, Belmore wore a white tank top that revealed the names of some of the murdered women written on her body in black. She vigorously scrubbed the cement in preparation for the ceremonial naming of the deceased while an audience member lit a candle for each woman. Once the candles were lit, Belmore put on a red dress and nailed parts of it to telephone poles that lined the alley. She then violently ripped the dress so that pieces of red fabric remained on the poles. To close the performance, she read the names of the women from her own body, one at a time. With the recitation of each name, she used her mouth to rip the thorns and leaves from red roses for each of the women. The candles, the red bits of fabric on the poles, the violently discarded roses, and ritualized naming of each woman formed the core of this performance.

17 Belmore also used her own body as a script that memorialized the murdered women and used ritual to bring the notion of embodiment to the centre of the performance. The performance piece became a video installation that was presented as part of the Talking Stick Festival in Vancouver, 2002. Belmore implicates her own Aboriginal body and suggests an intimate, ironic, and horrific counterpoint between her own very alive body, that vicariously experiences the violence of murder, and the dead bodies of the women she memorializes. As it must in Nolan’s and Clements’s plays, the audience is again forced to confront both the vitality and murder of Aboriginal women.

18 The memorializing and naming of missing Aboriginal women are still represented in performance today and continue to achieve the same transformative goal of commemoration and theatrical Medicine for murdered Aboriginal women in Canada. Aboriginal women who have gone "missing" are also commemorated in Aboriginal performance and new media artist Archer Pechawis’s performance "Elegy," which was first presented at the Talking Stick Festival in Vancouver, 2006. On his website, Pechawis states that this performance isa memorial to the missing women of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Using video projections and an original score by drummer/singer Anthony Favel and cellist Cris Derksen, ‘Elegy’ is a meditation on the lives of these women and on the tragically indifferent response of the Vancouver Police Department.4

19 Like "Vigil," "Elegy" also involved the lighting of candles and a ritualized naming of the missing women. As Aboriginal cellist Cris Derksen spoke the names and Pechawis lit a candle for each woman, their names were simultaneously projected onto a screen behind the performance space. Viewing an Aboriginal male engaged in this Medicinal and commemorative act, the audience was drawn to the gendered aspect of this performance. Unlike the plays I examined earlier and Belmore’s own use of her Aboriginal body, Pechawis’s male body implicitly added a new dimension to the mix—"Elegy" suggests the communal grief for both Aboriginal women and men.

20 In sum, Pechawis and Belmore used the medium of performance to document real Aboriginal women’s lives in such a way that the performances explicitly functioned as memorial rituals for the Aboriginal community and Canadian society. Pechawis and Belmore created their performances specifically for Aboriginal audiences within cities where there is still enormous grief about murdered Aboriginal women, and, so, it is fitting that they more explicitly use performance as community ritual and commemoration for Vancouver’s Aboriginal community. Aboriginal playwrights Clements and Nolan use the medium of theatre less explicitly to document and memorialize the lives of these women. In addition, each of these performances in their own way confront audiences with the issue of missing Aboriginal women in order to ensure that we remember their lives, their deaths, and their names.

21 Nolan sets in motion a revisionist narrative that, ultimately, allows the story of Aquash’s warrior activism to extend beyond the grave. Nolan’s Aquash character is murdered on stage and members of the American Indian Movement are implicated in the murder. The influence of the deceased is evident in the closing lines of both plays. In Nolan’s play, Aquash is given a first-person perspective on the intergenerational empowerment that her story will have on women. Clements, like Nolan, has created a play that extends the influence of murdered Aboriginal women beyond the grave, but her play does not show the murders on stage. Where Nolan ends with a prophetic speech about warriors living on after the close of her play, Clements uses a fictionalized revenge plot in order to extend a hopeful vision. Clements’s final scene is predicated on the power of the murdered Aboriginal women to effect a different outcome in the "real time" of the play and finally to achieve a crude form of justice.

22 Each playwright uses different narrative, visual, rhetorical, aesthetic, and dramatic means in order to suggest that these Aboriginal women have not been murdered in vain. Each playwright presents a feminist vision that suggests other women will be inspired (like the playwrights and performance artists themselves) to remember and retell these stories of resistance. If I consider the traditional teachings about Medicine that inform my central premise, I have to conclude that these performances are "good Medicine" addressed through ritual in the form of performances that ultimately heal. Each artist addresses the murder of Aboriginal women in performances that function as national commemorations. Together, these performances document, historicize, and elegize the deaths of Aboriginal women in Canada. As live performances, they create moments of collective remembering in Canadian theatre history, and, as a result, they are important examples of commemoration that have the potential to transform the trauma of the past.

Works Cited

Belmore, Rebecca. Grunt Gallery. Web. 15 Oct. 2007. <http://www.rebeccabelmore.com/home.html>

Bessai, Carl, dir. Unnatural and Accidental. By Marie Clements. Raven West Films, 2006.

Clements, Marie. The Unnatural and Accidental Women. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005.

Gilbert, Reid. Email to the author. 29 Nov. 2009.

Nolan, Yvette. Annie Mae’s Movement. Toronto: PUC Play Service, 1999.

Pechawis, Archer. Homepage. Web. 15 Oct. 2007. <http://www.apxo.net/home.html>.

Notes