Articles

Introduction: Marie Clements

Reid GilbertUniversity of British Columbia

you are not worthy of seeing. Extinct, like a ghost..."

(Marie Clements, The Unnatural and Accidental Women 82)

But inside it is a beautiful woman,

alive with happiness and living.

The ancient ones talk to us.

(Marie Clements, Age of Iron 7)

1 Marie Clements is a complex and fascinating theatre artist: dramatist, actor, and director. Her plays are intellectually provocative and challenging, presenting Aboriginal1 and feminist issues in a highly "painterly" style; her website describes Copper Thunderbird as a "two-act play on canvas." As Brenda Leadlay, Artistic Director of Presentation House Theatre, comments, the work is consistently "poetic, imaginative and moving." Mixing western theatrical practice with techniques of Aboriginal storytelling and ritual, Clements interrogates specific historical events (as, for example, the serial murders of Aboriginal women, the development of the atom bomb, the reductive depictions of "The Indian Musicale") and individual memories (as, for example, of domestic abuse, the traumatic residue of Residential school, and the repression of "The System Chorus"). As I have elsewhere argued at greater length, her vision is never simple. Typically, she considers a number of overlapping themes at the same time, simultaneously locating both the differences and the links among these political, racial, and gender strands in a layered semiosis ("Shine"). She combines visual and sound patterns,2 physical movement, and the fluidity of dreamscapes moving through time and space with hard, urban diction and apparently realistic plots ("Profile"). Her stylistic palate is equally complex: she embraces and—again—queries both the Western and Aboriginal modalities she employs, appropriates, re-appropriates, and revises (within the complexity of allusion in her early plays and more directly in her most recent work). Such hybridity and reference make her work compelling and invite examination; her work also presents a problem for analysis.

2 Clements views her own plays (and herself) as reflective of the interconnected subjectivities so obvious in Canada: amalgams of influences, histories, educational backgrounds, performance styles, races, and genders (Personal interview). Her work—as playwright, director, and Artistic Director—reflects the kind of performative negotiation Ric Knowles marked as characteristic of "all public performance in Canada [...,] constituting [...] subjectivities that have inevitably been displaced, hybrid, or diasporic: between settler/invader cultures and First Nations [and] among subsequent waves [...] of immigration" (v). Clements writes against this reality of historical dislocation and the silencing of First Nations voices, yet analysis that aims to salute this politic may, in fact, perpetuate colonization by employing Eurocentric methodologies and theories, especially if the critical voice is non-Aboriginal. Further, by alluding to Classical drama, Jacobean revenge, Renaissance Romance, pop culture, American television, and film noir (among other forms), Clements’s plays further challenge analysis: how to consider her use of such references without losing sight of her simultaneous critique of them in ironic, sometimes searing, and—even more problematizing—often tongue-in-cheek portrayals?

3 This collection of essays grew from papers originally presented at the Canadian Association for Theatre Research conference in 2008 and from a subsequent Call for Papers. Each of the authors who responded recognizes and acknowledges the problematic inherent in reading Clements, but necessarily speaks from her or his non-Aboriginal subjectivity and the training of the Canadian academy. I, therefore, invited Michelle La Flamme to write an article from her subject-position within the Academy, to give voice to a different tradition of performative medicine, and to offer a brief preface to the collection. For La Flamme, Clements is not only "Speaking up, Speaking out, or Speaking Back," but also "speaking within" both Aboriginal tradition and a growing collaborative network of Aboriginal artists. La Flamme links Clements to other playwrights in the Indigenous Performing Artists Alliance and to other Aboriginal artists who have carved out a space in which their concerns may be voiced by themselves.3 Although her play Copper Thunderbird was the first premiere of a First Nations work on the National Arts Centre mainstage,4 Clements remains concerned by the lack of opportunity for Aboriginal writers (Personal interview). She also worries that a general "levelling off" of interest in theatre will have a "trickle-down effect on Aboriginal theatre that is serious" (Personal interview). What seems clear, in fact, is that any revitalization of Canadian theatre turns on the emergence of previously mute voices creating what the Edmonton Fringe in 2003 called "theatre that challenges and celebrates the cultural fabric of our communities" (qtd. in Scott 4).

4 Clements’s latest work, The Edward Curtis Project, challenges representations of indigeneity. Presented by Presentation House Theatre as part of the 2010 PuSh International Performing Arts Festival and the Vancouver 2010 Cultural Olympiad,5 the show is a dialogue between a Metis correspondent, who "fears she is slipping from existence" (PuSh), and Curtis, whose romanticized photographs of what he imagined to be a vanishing Indian life are juxtaposed with contemporary photographs by Rita Leistner of a life that survives. Clements collaborated as well with composer Bruce Ruddell and Dene singer/songwriter Leela Gilday, mirroring the original partnership of Curtis with Henry Gilbert that produced the "Indian Musicale": here, Ruddell and Gilday revisit the early twentieth-century score to "de-Europeanize the songs" (Clements, Personal interview). The project is typical of Clements’s collaborative methodology (Gilbert, "Profile") and simultaneity of image, producing a multi-disciplinary revisioning of the historiographic record and staging a refusal to "vanish." As Leistner comments, "the present dynamic about appropriation and representation has always existed, but in the past it was subject to asymmetrical information. Today, we have the ability to address that dynamic in our work" (qtd. in Leadlay). Such collaborative performance/installations are educative, "speaking out" to address asymmetry, but they are also curative.

5 In "Theatrical Medicine: Aboriginal Performance, Ritual, and Commemoration," La Flamme offers a view of Clements’s work, and The Unnatural and Accidental Women in particular, from within a tradition of various forms of Medicine and a belief in the power of performance-as-Medicine. She contextualizes Clements with Yvette Nolan, Archer Pechawis, and Rebecca Belmore. In Annie Mae’s Movement, Nolan repositions the death of Annie Mae Pictou Aquash within the historical record, bringing the "disappeared" to the forefront, as Clements does with the murdered women in The Unnatural and Accidental Women. She also takes up the fraught question of Aboriginal feminism, a debate some find "an oxymoron" (as La Flamme puts it). She interrogates the complex position Aquash held within the male-dominated American Indian Movement. As Aquash states, "You gotta stand up, [...] you gotta fight for what’s important, no matter who wants you to shut up" (4).

6 Nolan re-enacts the murder of Aquash, placing the audience in the position of witnesses not only to her death, but to the deaths of those commemorated in a naming ritual: both powerful, Medicinal acts. She also shows the ongoing influence of Aquash, evidenced by the play itself, as testament to her refusal of silence. By evoking the power of absent but active women, and by naming them, the play recalls the chorus of women in Clements’s play, women who assist the protagonist, Rebecca, in her quest for retribution, but also lead her into the physical and communal space of her Aboriginal heritage. As La Flamme concludes, the plays are similar in their refusal to end the drama in the murder(s) of women, instead celebrating their "embodied and active presence."

7 La Flamme introduces two performance pieces by Pechawis and Belmore originally created for Aboriginal audiences, which also document the deaths of women in Vancouver as "memorial rituals for the Aboriginal community and Canadian society." In Belmore’s performance, the names of the women are written on the artist’s body; in Pechawis’s, the names are spoken and projected onto a screen in front of the audience, again cast as witness. As Belmore scrubs the concrete of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (the very pavements that form Earth Mother and from which she breaks forth in Clements’s Age of Iron6), she "implicates her own [living] body," calling for a communal remembering. In Pechawis’s piece, a man takes part in the commemorative ritual, his male body extending the discourse and suggesting a role for both men and women in the healing process. As La Flamme concludes, these four performances are good Medicine.

8 These same paved city streets are the physical setting for the thematic and visual imbrications of Clements’s play, Age of Iron, considered first in this collection by Sheila Rabillard. Discussing the implications in Clements "taking up the matter of Troy," Rabillard argues that Clements’s use of the myth is "highly selective and inventive," while reminding us that the story, itself, is the product of a history of borrowings and elaborations.7 Employing Bhabha’s notion of instability at the site of inscription, Rabillard reads Clements as narrating First Nations community through the Troy myth in a manner that is "multivalent, self-reflexive, and in a sense strategically divided against itself." Clements also deliberately presents the story as a re-telling, as a fiction. By transparently re-writing the ancient story, says Rabillard, the play ruptures the imperialist assumption that the written record is superior to the oral and questions the Western education imposed upon Aboriginal people. The play casts Aboriginal people as Trojans subject to the "System Chorus" of colonizers and their contemporary agents (cops and social workers), but complicates the allusion since, as Rabillard points out, the British who settled British Columbia claim descent from Trojan Brutus but are here cast as the invading Greeks. Once again, Clements does not allow easy inscription, "writing text at the intersection of discourses with quite different political and historical markers" (Gilbert, "Shine" 24) and celebrating the resultant slippages.

9 Using Hutcheon’s work on adaptive drama, Rabillard argues that Age of Iron disrupts any notion of the Greek drama as universalizing, making clear that her own story of Troy is a device, "a strategy for the occasion." And the duality of her characters—at once antecedent and contemporary—echoes and simultaneously "explodes" the original myth in order to "politicize its grief." The mourning extends beyond the figure of Hecuba, here pushing her shopping cart through the downtown streets, to include the male figure, Wiseguy; like Pechawis, Clements unites Aboriginal women and men in lament over their past, while offering only "a contested future." Clements further complicates issues of gender and responsibility in the figure of the street fighter, Raven, the Trickster who, as s/he always does, refuses stability and can act for, or against, her/his own people. In the overall pattern of the play, Rabillard traces "a transition from mourning to rebuilding community," yet Clements, she believes, "asserts a homeland which is also a place of exile." This place—pictured as the slums of Vancouver, but resonant with ancient myths of dislodgement and the historic subjugation of women—reappears in Clements’s next play, The Unnatural and Accidental Women.

10 Contributors bring a number of perspectives to their readings of this play. Karen Bamford places this story within a history of European drama and folk tales, especially examining "the genres of revenge tragedy and romance." Like others in this collection, she posits a "radical and feminist transformation" of the tradition by Clements, creating what Bamford calls a "maternal romance." Clements writes within a literary convention of selfless mothers returning from the dead to find and assist beloved daughters, but the mother she creates is not the type of the chaste woman; once again, Clements draws a more multifaceted picture. Aunt Shadie "embodies mother qualities of strength, humour, love, [and] patience," but she and her sisters—whose deaths at the hands of a serial killer are shown in Act 1—are also prostitutes and alcoholics, women who have, in some cases, left their families, and women who (in Act 2) make bawdy comments and jokes while inexorably moving toward their collective act of revenge. Within a dreamscape or memory narrative, these isolated and lonely women (and Rebecca) find and come to know each other. Bamford proposes "the scenes of past violence and grief—the motive for the revenge plot—are made bearable, by the divine comedy of the romance structure."

11 While the official reaction to these deaths was to ignore the victims, this variant of romance names the women (who are always shown as individuals with personal stories), and this "festive" conclusion, though expected in the romance tradition, follows the realization by their killer of the agency of the women in his execution. Indeed, while the revenge plot concludes, as does the quest narrative, the final image ("THE FIRST SUPPER—NOT TO BE CONFUSED WITH THE LAST SUPPER") is, in fact, a beginning.

12 This same empowerment of women is not, unfortunately, carried forward to the film version, significantly renamed Unnatural and Accidental. The change, as Erin Wunker succinctly states, removes "The. Women. An article and the subject." The play, which is so highly filmic in design, seems to invite a screen treatment, but the movie simplifies the allusions, moving almost entirely into the genres of Hollywood and television crime dramas. It silences and exhibits the women (none of whom is particular enough for the definitive article) and shifts subjectivity to the male killer (Gilbert, "From"). Using Phelan, Derrida, and Diana Taylor, Wunker claims that Clements’s play co-opts the power of a normalizing archive by building lines of communication among the women. If the play "destabilizes the semiotic archive," as she proposes, or "radically revises genre," as Bamford shows, or goes so far as to "denaturalize genre" itself, as I have previously argued ("Marie"), the film, as Wunker demonstrates, "co-opt[s the project, moving the action and its traces] back into the totemic patriarchal archive."

13 Wunker compares the two media, detailing important changes and omissions in the film and building a case for an "ethics of witnessing," initiated in the play by Aunt Shadie in her meeting with the English telephone receptionist, Rose—who is absent from the film. As Wunker points out, "the repercussions [of this absence] are highly visible," as the film denies the interchanges among the women that are crucial to the play’s resolution, removes the inter-racial bonding, and isolates each story for the camera’s scrutiny. In the final film adaptation (which differs in key ways from the original screenplay by Clements who does not find this version "gratifying, as an artist" (Message), the camera claims the gaze, the audience loses its subjectivity just as the women do, the execution of the killer becomes simply another sensational murder, and the film incorrectly names Aunt Shadie as object petit(a), falsely suturing over loss and misrecognition, and returning the viewer to the scopophilic field of cinematic desire (Gilbert, "From"). Indeed, as Wunker concludes, "the moment of destabilizing (mis)recognition is lost [...,] sacrificing the majority of the play’s radical gestures."

14 Giorgia Severini returns attention to Age of Iron. She applies Bhabha’s concept of the Third Space but questions the limits of this theory, noting "hybridity does not stop whiteness acting with the power to Other." As she observes (as does Rabillard), even "whiteness" is a hybridity developing through time and a complex of mythologies and "individual and collective narratives of oppression," but, "in the end, whiteness still appears to be dominant" and resistant to the Third Space. (The treatment of Metis people in Canada serves as a chilling reminder of this intolerance and is particularly apt, given Clements’s heritage.)

15 In this version of the myth, Cassandra is a central character: abjected by the dominant culture, as well as by men in her own community, and yet determined to recount the history of her abuse at Residential School: she is a woman to whom no human will listen. She can, however, speak with Earth Mother and the stars of the Sister Chorus of erased women who await her arrival. In associating Cassandra with the Sister Chorus, argues Severini, Clements reinscribes the "cultural significance of the Pleiades [...] to address the present-day oppression of First Nations women." These women speak from a place generated by a new myth applied backward onto the old (which, La Flamme suggests, is a worthy enterprise, and Lacan might propose is a consequence of the inevitable effect of retroversion8), but, observes Severini, "the resulting space is one that exposes hierarchies. It is not able to fully dissolve the oppressive hierarchies." There are no easy solutions for Cassandra or her comrades, as there are no simple answers for the audience of any Clements play. Finally, Cassandra urges Raven (who has raped her, but now acknowledges her power) to sing, "so others might hear and know they are not alone." This forging of an alliance between Aboriginal women and men, suggests Severini, is, at least, hopeful. As Rabillard warns, such hope resides within exile, but Severini argues that a turn inward is a positive step toward new negotiations of subjectivity.

16 Notions of self-identity within community and of hybrid subjectivity arise again, but position themselves quite differently, in Nelson Gray’s consideration of The Girl Who Swam Forever, an early play that Gray directed at UBC in 1995 and which was revised for publication in 2008. Reading the play from an ecological perspective, Gray acknowledges and resists the colonizing image of the "noble savage," but he argues that the "anthropocentric assumptions endemic in Western thought" are equally normalizing. He claims Clements employs "an entirely different set of assumptions to situate her post-colonial politics within a vision of self and world that is unequivocally eco-centric."

17 Clements drew upon three sources for this play: oral tales of the Katzie people, media reports of sturgeons beaching themselves on the banks of Pitt Lake, and a book by Terry Glavin that provides the history of the traditional relationship between these ancient fish and the Katzies. In a characteristically tiered style, Clements weaves these histories together with the story of a young woman running away from Residential School and becoming pregnant by a non-Aboriginal man, to create a "dream-like underwater transformation" in which the woman "encounters her grandmother’s spirit in the form of a hundred-year-old sturgeon lying buried in the thick mud of a polluted river." The play, according to Gray, is a "post-colonial politics enfolded in an ecocentric vision." While acknowledging that such a worldview is alien to Western ontologies, Gray suggests (Western) "animist ideas of transformation and inter-subjectivity [...] inform the conflict and resolution in the play." Gray believes they may also offer a possible answer to the questions of identity and belonging implicit in inter-racial birthing and central to this story. Drawing on Deleuze and Guattari, he proposes a "becoming" that avoids "the binary thinking that would define one race against another and that would conceive of nature and culture as opposites."

18 Such an idea of becoming—of moving among translucent layers of self, dream-self, historical/fictional self, and memory; of finding centre and agency in a community that may extend beyond the human or the concrete; of emerging from a chrysalis of ancient traditions, myths, and ontologies; of becoming-by-speaking out—is fundamental to Clements’s vision and informs all her work. In Copper Thunderbird, she traces the "powerlines [among] Objibway cosmology, [a] life on the street, and [the] spiritual and philosophical transformations" that crafted Norval Morrisseau as "The Father of Native Contemporary Art, and a Grand Shaman" (Clements, Homepage). Such "powerlines" also reverberate through the intricate semioses of Marie Clements’s plays: reversing erasure; bridging races; and connecting women with their heritages, with men, and with each other. They speak from the Lacanian Real, gathering their strength in the jouissance of women (Gilbert, "From"). Though invisible except to the theatrical eye, they bring visibility to lives that must be seen. Though silent, they bring volume to voices that insist on being heard.

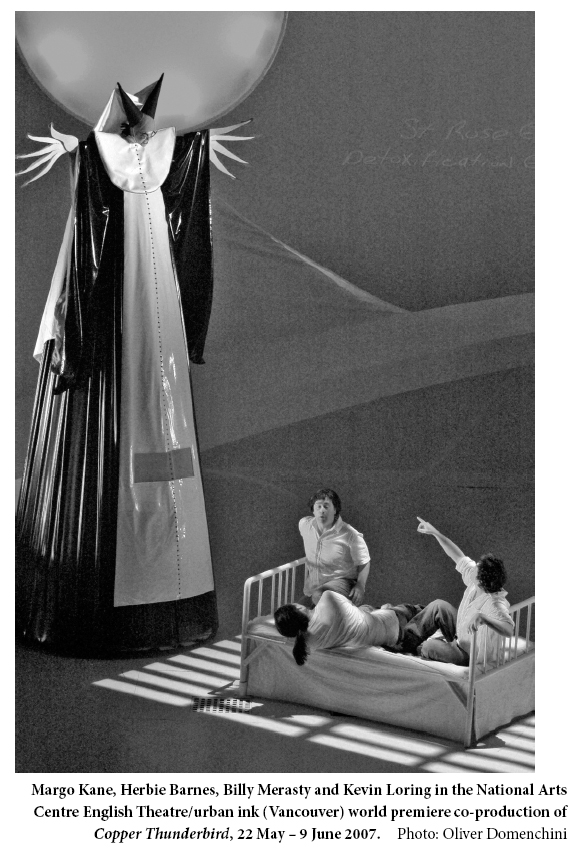

Margo Kane, Herbie Barnes, Billy Merasty and Kevin Loring in the National Arts Centre English Theatre/urban ink (Vancouver) world premiere co-production of Copper Thunderbird, 22 May — 9 June 2007. Photo: Oliver DomenchiniWorks Cited

Clements, Marie. The Unnatural and Accidental Women. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005.

— . Email to the author. 3 Mar. 2008.

— . Personal interview. 21 Jan. 2010.

— . Homepage. Web. 18 Feb. 2010. <http://www.marieclements.ca>.

Gilbert, Reid. "From Trapper to Trapped: Marie Clements’s The Unnatural and Accidental Women in Three Media." CATR/ACRT conference. University of British Columbia. May 2008.

— . "Marie Clements’s The Unnatural and Accidental Women: ‘Denaturalizing’ Genre." TRiC/RTaC 24 (2003): 125-46.

— . "Profile: Marie Clements." Nations Speaking: Indigenous Performance Across the Americas: Special issue of Baylor Journal for Theatre and Performance 4 (2007): 147-51.

— . "Shine on us, Grandmother Moon’: Coding in Canadian First Nations Drama." Theatre Research International 21 (1996): 24-32.

— . "Staging the Pacific Province." Canadian Theatre Review 101 (2000): 3-6.

Knowles, Ric. Introduction. Performing Intercultural Canada: Special issue of TRiC/RTaC 30.1-2 (2009): v-xii.

Leadlay, Brenda, in conversation with Marie Clements and Rita Leistner. PuSh 2010 Curatorial Statement: The Edward Curtis Project. 12 Jan. 2010. Web. 8 Feb. 2010. <http://pushfestival.blogspot.com/2010/01/push-2010-curatorial-statement-edward.html>.

"Norval (called Copper Thunderbird) Morrisseau: Artist and Shaman between Two Worlds,1980." Cybermuse. National Gallery of Canada/Musée des Beaux Arts du Canada. Web. 20 Feb. 2010. <http://cybermuse.gallery.ca/cybermuse/search/artwork_e.jsp?mkey=104329>.

Nolan, Yvette. Annie Mae’s Movement. Toronto: PUC Play Service, 1999.

PuSh International Performing Arts Festival. PuSh Jan. 20-Feb. 6, 2010. 20 Jan. 2010. Web. 12 Feb. 2010. <http://pushfestival.ca/index.php?mpage=shows&spage=main&id=102>.

Robinson, Donald C. "Introduction: Norval Morrisseau Exhibition, ‘Honouring First Nations.’" Kinsman Robinson Galleries, Toronto, 1994. Cybermuse. National Gallery of Canada/Musée des Beaux Arts du Canada. Web. 26 Feb. 2010. <http://cybermuse.gallery.ca/cybermuse/docs/bio_artistid3864_e.jsp>.

Scott Shelley. "Cultural Diversity at the Edmonton Fringe Festival." alt.theatre 3.1 (2004): 4-5.

Žižek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. London and New York: Verso, 1989.

Notes