Articles

Kneading You:

Performative Meta-Auto/Biography in Perfect Pie

Jenn StephensonQueen's University

Abstract

In the last two decades, it has become an accepted principle in psychology that the sense of self depends on autobiography. Without the ability to organize experience through narration, arguably one cannot have a coherent self. If one’s self is indeed dependent on autobiography, then that same narratively constituted fictive self is especially susceptible to erosion and erasure through memory loss and narrative disability. In Judith Thompson’s Perfect Pie, Patsy is such a character, suffering from trauma-related amnesia that inhibits the realization of a full extended self. Although on the one hand, Patsy’s status as a fictive character leaves her vulnerable to the power of words to undermine the stability of a narratively generated self, on the other hand, her ontological situation as a character born in words also grants her significant power to wield that same performative power to write her self. This article will examine the dialogic self-authoring strategy that Patsy adopts to generate multi-vocal autobiography, weaving thematically associated stories across disparate nested fictional worlds. Ultimately, Patsy’s potential cure lies not in the revelation of an objectively-verifiable historical truth but rather in the pie-making, theatre-making, self-making process of continued reiterative performance.Résumé

Au cours des deux dernières décennies, les psychologues se sont entendus sur le principe selon lequel le sens de soi est tributaire de l’autobiographie. Si on ne peut organiser l’expérience par un fil narratif, il est impossible de construire un soi cohérent. Si le soi compte effectivement sur l’autobiographie, ce même soi constitué par la narration est spécialement susceptible de s’éroder et de s’effacer sous l’effet de l’amnésie ou d’un handicap lié à la narration. Dans la pièce Perfect Pie de Judith Thompson, le personnage de Patsy souffre d’une amnésie liée à un traumatisme, qui l’empêche de se réaliser entièrement. Si, d’un côté, son statut de personnage fictif expose Patsy au pouvoir qu’ont les mots de miner la stabilité d’un soi généré par la narration, de l’autre, sa situation ontologique de personnage créé par les mots lui accorde également un pouvoir important, celui d’utiliser ce même pouvoir performatif pour s’écrire. Cet article examinera la stratégie dialogique d’écriture de soi qu’adopte Patsy pour produire une autobiographie plurivocale en tissant des récits associés sur le plan thématique à partir de mondes fictifs disparates. En bout de ligne, la solution éventuelle ne repose pas dans la révélation d’une vérité historique objectivement vérifiable, mais dans l’acte de fabriquer des tartes, de faire du théâtre, de se créer soimême, un processus de performance qui se réitère en permanence.1 Self cannot be separated from narrative. It seems a bold claim, but there it is—we cannot live without stories. In the last two decades, it has become an accepted principle in psychology that the sense of self depends on autobiography (Neisser; Brewer; Ochs and Capps). Naturally, narrative arises out of experience as we tell the stories of our lives; but conversely, the storehouse of experience—the self—is not only shaped by, but actually created out of narrative. One major proponent of this constructivist theory of the narratively generated self, Jerome Bruner, argues in "Life as Narrative" that worldmaking is the principal function of mind. Just as physics or art or history are modes of making a world (Goodman), likewise narrative is also a way of worldmaking and autobiography a way of "lifemaking" (Bruner 12). Bruner goes on to argue that "we seem to have no other way of describing ‘lived time’ save in the form of narrative. Which is not to say that there are not other temporal forms that can be imposed on the experience of time, but none of them succeeds in capturing the sense of lived time" (12). Not only does narrative best describe life, but life itself is made out of narrative: "Life [. . .] is the same kind of construction of the human imagination as ‘a narrative’ is. It is constructed by human beings through active ratiocination [. . .]. In the end, it is a narrative achievement. There is no such thing psychologically as ‘life itself’" (Bruner 13). And so, just as life is entwined with narrative for us, flesh-and-blood citizens of the actual world, it is even more so for citizens of fictional worlds since the lived experience of these characters is always already formed in words. Divorced from a specific actual embodied self, a fictional self is a purely performative creation. Having already been created once through the performative act of a playwright, fictional characters experience auto/biography-within or what I am calling meta-auto/biography as an applicable reiteration of their own basic constitutive process. But, if one’s self is dependent on performative auto/biography, then that same narratively constituted fictive self is especially susceptible to erosion and erasure through memory loss and narrative disability.

2 Setting aside the idea of a unitary self, psychologist Ulric Neisser proposes a model comprising five aspects of self, reflected in the ways in which individuals know themselves: the ecological self, the interpersonal self, the extended self, the private self, and the conceptual self. Among these disparate selves, it is the extended self that deals particularly with memory and anticipation, projecting the self forward or backward in time. Two kinds of memories contribute to the extended self: episodic memory, which is the recollection of specific experience (things I can remember having done), and procedural memory, which encompasses repeated and familiar routines (things I think of myself doing regularly) (47). Amnesia is the primary pathology of the extended self.

3 Patsy, the central character of Judith Thompson’s 1999 play Perfect Pie, suffers from trauma-related amnesia that inhibits the realization of a full extended self. In her case, the injury damages her episodic memory leaving experiential gaps, but her procedural memory remains intact. Although on one hand, Patsy’s status as a fictive character leaves her vulnerable to the power of words to undermine the stability of a narratively generated self, on the other hand, her ontological situation as a character born in words also grants her significant power to wield that same performative power to write her self. Drawing on the cognitive pairing of procedural memory and episodic memory, Patsy uses strengths in one to supplement faults in the other. Two monologues by Patsy and addressed to her absent childhood friend Marie frame Perfect Pie. Underscoring these speeches, Patsy rolls pastry dough and goes through the steps of making pies. Beginning with the conjoined acts of pie-making and story-making, Patsy slowly progresses toward self-making. The reflexive process of undertaking performative autobiography, then, becomes not simply self-discovery but a radical act of self-creation.

4 Set in a farmhouse near the town of Marmora in Eastern Ontario, the story of Perfect Pie proceeds along two parallel paths. One day, Patsy is visited by the estranged Marie, renamed Francesca and now a well-known actress. Interspersed with the conversation of the adult women are moments from their past, performed by a second set of younger actresses. As the play progresses both timelines converge on a critical series of events. These traumatic events are the root of Patsy’s amnesia and narrative disability. Patsy’s memory loss manifests in disparate ways but all her symptoms originate with the last night she and Marie were together as teenagers. On that night of the Sadie Hawkins dance, while Patsy stayed at home with a fever of 104°F, Marie was sexually assaulted by a gang of local boys. Later, the shell-shocked Marie and feverish Patsy cling together as they face an oncoming train. The resulting crash leaves Patsy in a coma. When she wakes up her friend is gone. This is the primary loss; Patsy has an experiential rupture, commencing with the crash of the train and ending with her revival eight weeks later. During this missing time, Marie has disappeared and Patsy’s ignorance (or traumatic repression) of her friend’s fate troubles her. Moving backwards chronologically from the crash, Patsy suffers other uncertainties and gaps. Neither Marie’s account of her assault nor Patsy’s witnessing to that account are very coherent. Caught between Marie who is rambling in her distress and Patsy delirious with fever, even the audience receives only a fragmentary impressionistic sense of what happened. As Patsy says later, "But I wasn’t sure... You know, you were talking so—so—fast... And wild, you were turning in circles and... you were, like, in a state of shock, I guess" (21-22). Arguably, Patsy shares in her friend’s emotional trauma, which closes off access to those events. Trauma has a direct relation to memory, causing a violent experience to be effaced; that is, the emotional toll of the original experience overwhelms the subject, and to protect the fragile self the traumatic experience is closed off. And without the imprint of the original experience that event cannot later be recalled as memory: "What returns to haunt the victim… is not only the reality of the violent event but also the reality of the way that its violence has not yet been fully known" (Caruth 6).One more lasting effect of Patsy’s injuries is that she is now afflicted with epilepsy and experiences regular grand mal seizures. A mundane explanation for the onset of her seizures is that concussion can trigger epilepsy. The more magical explanation is that at the moment of the train crash, Patsy and Marie merged, and in the exchange Patsy has assumed Marie’s condition. Epilepsy causes amnesia, not just in the duration of the seizure itself but repeated seizures inflict ever more damage to the brain, increasing memory faults. Linking her epileptic seizures to Marie’s assault as well, Patsy describes one of her seizures in sexualized overtones as rape by a stalker (50-51). This too supports the hypothesis of transference of shared emotional trauma from Marie to Patsy in the moment of the crash.

5 This pathology precisely matches a condition Kay Young and Jeffrey L. Saver term Unbounded Narration in their study "The Neurology of Narrative." While other types of amnesiacs categorized by Young and Saver either lack basic narrative ability (Denarration) or suffer narrative impairment (Arrested Narration, Undernarration), Patsy exhibits an imaginatively rich and multi-faceted capacity for storytelling. Those afflicted with Unbounded Narrationdevelop confabulation, restlessly fabricating narratives that purport to describe recent events in their lives but have little or no relation to genuine occurrences [. . .] [Stories are told] not from a desire to impress, entertain, instruct or deceive, but simply from a desire to respond to another human being’s query with a story. (76-77)Paul John Eakin in his book How Our Lives Became Stories notes that "there is always a gap or rupture that divides us from the knowledge that we seek" (x). He explains that the knowledge we seek is the experience of catching ourselves in the act of becoming selves. Self-reflexive autobiography is one way of looking into this gap. Patsy’s propensity, then, for storytelling is a narrative dysfunction, but it is also appropriately therapeutic. By looking into the gaps in her memory, Patsy not only hopes to catch a glimpse of herself in the act of becoming a self but also to fill those gaps with narrative, regardless of whether or not her autobiography can be authenticated in connection with actual past events. And by doing so, to author a new whole self.

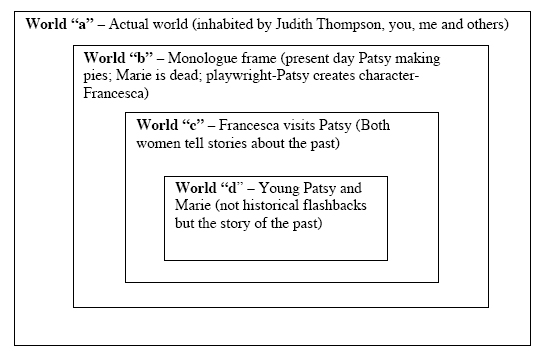

6 Philippe Lejeune, in a seminal text for autobiographical studies, proposes a kind of social contract that directs the veridical expectations of a reader engaged with autobiography. In an attempt to distinguish autobiography proper from first-person novels, Lejeune sets out a number of criteria, but ultimately only two are definitive: First, the author, narrator, and protagonist must be identical and, second, the author/subject must be a real person (5). Figured as a self-story, autobiography actively fosters the assimilation of author, narrator, and protagonist under the single pronoun "I." But, from the perspective of the autobiographical story as aesthetic creation, these three roles do not share equivalent ontological status; they reside instead in a series of nested worlds which we can imagine as a set of concentric rings. The outermost ring comprises the actual world and the autobiographical subject is an autonomous citizen of this world—designated worlda. The narrator, albeit a mirror of the subject and voice for her thoughts, is her fictional creation. This narrative figure is a selective and not fully determinate doppelganger, residing in the inner circle of worldb. Next, the protagonist is the narrator’s character. Although the character is conjured in the first person as "I," nevertheless this "I" is subject to the descriptive control of the narrator. This "I" is yet another layered persona-within, belonging properly to worldc. By affirming the identity of these three roles, Lejeune’s autobiographical pact emphasizes their congruence as aspects of the worlda subject and minimizes their necessarily fictive separation arising out of the constructive act of writing a life. The novel form also conspires to elide this graphical difference by rendering subject, narrator, and character invisible, giving to the reader the illusion of direct and unmediated intercourse with the authoring subject. The textual symbol "I" speaks ambiguously for all three personae.

Display large image of Figure 1

7 However, the dramatic form in performance, which replaces the printed "I" with a fully determinate actor body, works in the opposite direction, tending to highlight the ontological separation of roles. In the theatre, we are always confronted by the embodied actor who is ambivalently both an actual-world person and a fictional-world character. Embodied autobiographical performance fosters tension between the biological equivalency of the subject-author and the protagonist and the necessary ontological difference between creator and character. This situation further augments perceptual slippage between the fiction and the actual-world referent. Even in identity, both performer and audience still must engage with the multiple ontological roles of autobiography. Although Lejeune’s pact fosters a unified view of the autobiographical "I," and the essential duality of theatre demands that these "I’s" be kept separate, the theatrical imperative need not nullify the autobiographical pact. Both these audience attitudes can be held in a productive tension.

8 Amnesia also problematizes the expected unity among these autobiographical roles. Not only are the roles of author/subject, narrator, and protagonist separated by ontology as shown above, they are also divided by time. Each role engages the narrative self from a different perspective and with different knowledge. Without memory, the bridge between the past subject and the present author breaks down. Self and narrative are interdependent, mediated by memory. Without memory there can be no narrative, but similarly without memory there can be no self.

9 Unable to fill her experiential gaps through direct liaison among the tripartite self of subject, narrator, and protagonist, Patsy applies a cross-world metatheatrical strategy to weave a new self story. In this way Patsy-as-playwright-within in Perfect Pie exemplifies a strategy that is increasingly common in contemporary Canadian metadramas, moving across ontological levels to generate stories-within-stories and using insights gained from her fictional forays to illuminate actual world problems.1 Patsy as playwright darns cognitive holes with discovery but also with creation.

10 Another core feature of autobiography is that it is always relational. Whereas the autobiographical pact considers the vertical relation of subject-narrator-protagonist, there is also the horizontal relation to be accounted for. Even the self-story of a single individual includes the story of others—parents, children, spouses, friends, and acquaintances. And so autobiography implies biography. Conversely, biography also entails autobiography. Focusing on the process of creating biography and autobiography, Susanna Egan, in her book Mirror Talk: Genres of Crisis in Contemporary Autobiography, targets this particular relational aspect of biography, which blurs the traditional distinction between biographer and subject. Invariably, in such narratives, the biographer him/herself becomes the subject as well. She identifies the graphic novel Maus by Art Spiegelman as a key example of this phenomenon. In Maus, the story is divided between the biography of the father Vladek and the shared experience of father and son in the recounting of that story and so both men stand both inside and outside the narrative. Taking on dual roles as both autobiographer/biographer and biographical subject, these paired characters each straddle two worlds.Mirror talk, for Egan, then, is plainly "the encounter of two lives in which the biographer is also an autobiographer" (7). This is the reason for my use of the blended and/or construction "auto/biography." It is intended to denote the interdependent dialogue of the primary autobiographical subject and the biographer who finds her own life inextricably reflected and embedded in the shared process of creating a narrative self: "Such collaborations seem far less concerned with mimesis, however, than with authenticating the processes of discovery and re-cognition" (7). This focus on the processes of self-discovery and renewing cognition is especially relevant to the potential for auto/biography in Perfect Pie where the central character suffers significant memory loss, making recovery of an objectively authenticated past difficult at minimum and, in some important ways, impossible.

11 Typically mirror-talk pairs share an ontological equivalency both inhabiting the same world and working interdependently to tell the story of two lives. In Perfect Pie, however, mirror-talk roles are blurred with these usually disparate perspectives housed within a single intra-dialogic person. Although Perfect Pie is populated by four characters—Patsy and her friend Marie as children/teenagers and the older Patsy and an older Marie who has changed her name to Francesca—the geography of the narrative structure is such that they do not have equivalent status. In fact, as I will argue, Patsy is quite alone. Through the hierarchical organization of stories-within-stories and worlds-within-worlds, the adult Patsy is established as the preeminent playwright, ontologically superior to the others who are her fictive creations. From one perspective, the arrangement of the two pairs of girls and women, divided between past and present,seems like a straightforward use of memories or flashbacks nested into a present-day main narrative.2 However, the play subverts this simple understanding, suggesting quite strongly that Francesca is not real. Marie did not survive the train crash and the older version of Marie as Francesca has been conjured into existence by Patsy.3 Drawing evidence from Patsy’s opening monologue in which she declares, "I know in my heart you did not survive" (4), several commentators acknowledge that "the narrative line is ambiguous enough for the whole play to be read in retrospect as a story about Patsy keeping the precious gift of her dead friend alive in memory" (Nunn 320-1; cf. Moser).4 However, this interpretation has significant repercussions for the play as auto/biography. If Marie’s survival as Francesca has been authored by Patsy, then all the ‘present day’ scenes of the two women as adults are also a fictive creation. So, Patsy as playwright has given birth to the adult Francesca but also to a fictive version of herself. The borders between worlds have become permeable and Patsy of worldb is talking to her own character born into worldc. Thus, Francesca is Patsy’s mirror-talk partner. Patsy has created her own mirror, bringing Marie into the present, reincarnated as Francesca. This scenario of cross-world mirror talk is further complicated by scene two, which consists only of this stage direction: "Light on MARIE/FRANCESCA, in her own dark apartment in the Big City, a great view of the city at night behind her. She remembers..." (4). The illumination of Francesca marks her ‘birth’ into worldc through Patsy’s creation, yet critically the stage direction "She remembers..." admits her as a co-creator of the past memories of worldd. Just as Patsy is ontologically fragmented by her amnesia, so the character of Francesca is not fully contiguous with Marie. Autobiography normally separates the narrator from her created protagonist in time, but here that gap is exacerbated by the ambiguity of Francesca’s existence and Patsy’s memorial control over both the historical Marie and the fictive Francesca. This persistent ambiguity regarding the genealogical links between author/subject, narrators, and protagonists precludes any possibility of accommodating Lejeune’s expectation of a reliable unitary identity across roles.

12 Because Patsy is the primary playwright of Perfect Pie (we never hear anyone else’s voice), all the stories she tells are reflections of her own creative process. Rather than pursuing a resolutely linear search, Patsy’s narrative is linked associatively. And instead of applying performance directly to repair a damaged self, Patsy makes her lost friend as a pie. Her preoccupation with pie-making and her thematic associations with pies embedded in her monologue and subsequent nested fictions are all part of her process of self-reconstruction. She metaphorically blends her use of performative language with her culinary art of assembling pastry and fillings to create both past Marie and present Francesca. During her opening monologue/letter to Francesca, Patsy makes a rhubarb pie and sends it in the mail to her friend. In the final framing speech of the play, Patsy begins to craft another pie and makes explicit the Francesca-as-pie metaphor: "And I’ll be looking at the snow and I will feel the pastry dough in my hands and I will knead it and knead it until my hands are aching and I think I’m making you. I like... form you; right in front of my eyes, right here at my kitchen table into flesh" (91). It is noteworthy that the rhubarb pie-filling of the play is substituted for steak and kidney in the pies Patsy makes in Thompson’s 1994 monologue "Perfect Pie," which constitutes an ur-text for the play. As in the play, Patsy’s earlier monologue is accompanied by actions of pie making. Images of internal organs and organ meats linked with Patsy’s mother’s cancer and the dead Marie permeate this monologue (167, 170). The plot of the monologue deviates from the play quite significantly in relation to Patsy’s friendship with Marie. In the full-length play, Patsy is Marie’s stalwart defender. She seems to hold her own against other kids at school, while maintaining a close friendship with the bullied Marie. In the monologue, however, Patsy buys her way into the dominant social circle by betraying her friend: "I know, I promised you, I swore on the lives of my future kids, I would never tell a soul as long as I lived and I never planned to tell at all, Marie, not at all. It just spilled out of my mouth. Like organ meats" (166). Organ meats are associated with Marie and also organ meats are the story, the telling of the secret spilling out. Patsy’s crime then is the telling of Marie, Marie herself being a prohibited story. The parallel processes of Marie created by a story and Marie baked as a pie are much more clearly aligned in the earlier monologue; nevertheless, traces remain in the play. Since Patsy is the author (perhaps in combination with Francesca) of the past memories, the selection of these memories is significant. Many of the memories of the younger girls concern moments in which Patsy ‘improves’ Marie: Patsy gets rid of her lice, carefully picking out her nits and covering her hair with margarine (29-30). Patsy advises her that she needs to bathe more regularly (68-69). Patsy corrects her language (38). Finally, Patsy dresses her for the dance: she brushes her hair; she does her makeup, Patsy having even sewn the dress (76-79). Marie is Patsy’s art. In an act of projection, when Patsy imagines her lost friend into the future she calls her Francesca ("free") and makes her an actress, someone who makes new characters with her own voice and body.

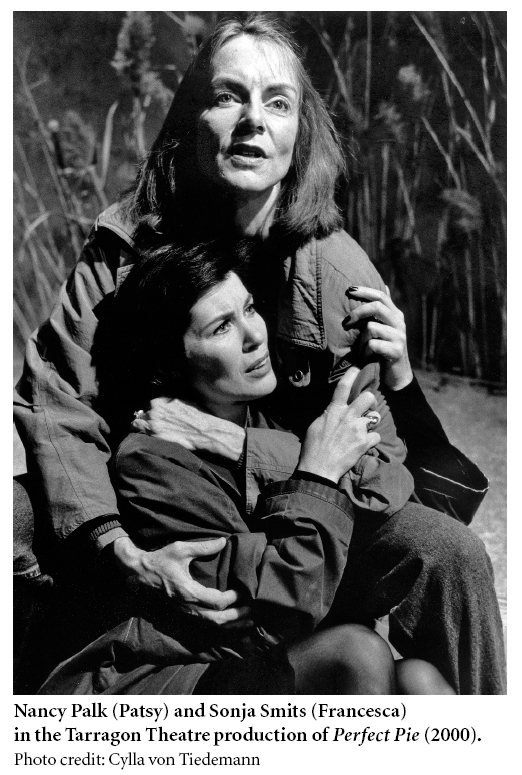

Nancy Palk (Patsy) and Sonja Smits (Francesca) in the Tarragon Theatre production of Perfect Pie(2000).

Display large image of Figure 2

13 If Francesca is a pie, is she perfect? Pies in Perfect Pie are prizewinning but are also burnt and frozen. Leaving aside burning pies for the moment, ice images pervade the play. Virtually every nested-narrative in the play is associated with ice or snow. More than once the word "Ice" is used with anomalous capitalization (7, 76, 79). "Ice" seems to function as a trigger word, a key which opens up other memories. In addition to Patsy’s experience of narrative disability stemming from basic memory faults, individuals with epilepsy also often have difficulty with retrieving memories out of context. The memories have been correctly stored but access is blocked. Moreover, a distraction, in the form of a similar memory, can also become an obstacle to memory (Barr). The seemingly random collection of stories told by Patsy and by her subordinate fictive personae appears to cohere in this way. They share similar associative elements, which may or may not be helpful, as Patsy circles to get closer to the hole at the centre. One therapeutic technique used with amnesiacs requires a psychologist to provide random words, attempting to draw up associated memories, as the afflicted person works gradually closer and closer to the temporal borders of the empty landscape of the post-traumatic amnesia period (Crovitz). This seems to be what Patsy is doing.

14 The first image is ice, specifically the emotional impression that ice is beautiful and romantic. Young Patsy describes kissing as like making strawberry ice cream by hand: "it’s getting colder and churning and if you put your face in right into the churning ice cream at that moment when it’s going pink with the red juice and turning from cream to ice cream.. THAT... is the moment of a kiss" (74). As an adult Francesca narrates in detail a dream of living alone in the Arctic "near water, and giant shifting icebergs, surrounded only by violets and snowdrops and rough weeds, with the occasional hare racing by my little snow house" (59). Just as the red juice of the berries blends with the cold cream, and there are flowers in Francesca’s arctic imaginings, quite a few of the ice and snow images combine some living thing covered over by snow, sometimes beautifully preserved in death by the cold. In their first meeting as children, Patsy invites Marie to her birthday party: "We’ll be skating on the river" (14). Also there will be a game of musical chairs using a "really cool song about this pretty girl who is on her way to a party? And it’s like really cold like a hundred below zero and so she like falls asleep in the snow and she freezes in her Sleighride thing?" (14). Later, there is a quite lengthy scene as the girls act out this song, Patsy calls herself Annabel Lee (a likely reference to the poem of the same name by Edgar Allen Poe)5 and Marie becomes Bon Bon McFee (41-43). In act two, scene eight, Marie rehearses an audition monologue. Patsy describes her audition rhyme saying, "It was the one about these girls? Skating in the summer? And falling through the ice…" (62).6 The name that Patsy gives herself "Annabel Lee" connects to two other deaths in Perfect Pie. Annabel is also the name of Patsy’s stillborn daughter: "I kissed her sweet little face with the white down, her toes,like Lily Of The Valley… But I did not cry" (54). She is not frozen but the imagery of being covered in white down and white lilies is analogous. In this thematic rhizome, Patsy’s narrative compounds the image of ice as a romantic kiss or utopian landscape to ice as a frozen idealized beautiful death.

15 As she continues to circle around the amnesiac block, she associates the baby Annabel with another "Belle"—the lost dog of Patsy’s childhood. In a non sequitur at the end of one scene, Patsy wishes for the return of her dog: "She’s been gone for so long" (57). In another scene a little later, she recounts unexpectedly discovering the dog tied to a tree, dead. The description of the rotting corpse of the dog is gruesome. This death with the flies and the smell and Patsy gagging is far from the bloodless perfectly preserved icy deaths of the first two Annabels. Following this thematic line still nearer to the amnesiac blank time, Patsy adds Marie to this catalogue of lost beloveds. Frequently, Marie in her tormented and scapegoat state is associated with dogs. Patsy brushes dog shit off Marie’s coat. The boys call her "You Dog" (84). She herself says "I’m the town dog" (74). As an adult Francesca describes Marie as "a weird sister I have dogchained in the attic" (6). As with Belle, Patsy yearns for her return, made impossible by her death. And in contrast to the ‘beautiful’ deaths of Annabel Lee and the baby Annabel, the dog Belle’s body in death is grotesque, and so we might imagine would be Marie’s.7 And with this Patsy gets right to the edge of the blank space, almost to the brink of knowledge for the thing she cannot see.

16 Following this thematic spiral, the thing that floats just beyond Patsy’s awareness is Marie’s corpse. Already filthy and distressed from the boys’ assault, Marie’s body is crushed by the impact with the train. We can only imagine what Patsy saw. Although the play, Perfect Pie, progresses chronologically toward the dual trauma of sexual assault and the train crash, these are not the events that need memorial reconstruction. The thing Patsy does not remember is what happened to Marie after the train crash. This reading I am suggesting in which Patsy’s associations lead to this horrific image opens up two possibilities: either Patsy did see the mangled corpse of Marie and has suppressed that traumatic image of her dead friend or she truly does not know,and this traumatic image is one that she has conjured but will not actively consider. There can be no definitive answer. Likewise, although this narrative cycle enacted in Thompson’s Perfect Pie moves Patsy close to admitting this image, the amnesiac block is not removed. And yet, the cyclical structure of the play, beginning and ending with the same phrase and actions, implies that there will be other attempts, one of which may succeed.

17 These narrations spiralling towards this blank at the centre span several ontological levels: the fictive Francesca living in worldc tells her dreams creating a worldd, young Patsy—herself already several fictional worlds removed from Patsy the principal narrator—narrates her own past experience in discovering her dog, the girls assume the characters of Annabel Lee and Bon Bon McFee to perform the play-within of the sleigh ride, and so on. Patsy uses these stories-within to create a cross-world rhizomatic network in an effort to fill in the blank spaces of her own history. The self that emerges is not singular or necessarily coherent but rather takes its strength from its multiplicity of perspectives, putting down roots in multiple fictional worlds. Patsy makes deliberate use of explicit theatrical duality to build the bridge between subject and protagonist, finding herself in the stories of herself. For an autobiographer engaged with another actual person—a person who resides on a shared ontological level—there can be some promise of equivalency between the present subject and the past protagonist as his or her recollections are supported and authenticated as ‘true.’ For Patsy, as a solitary auto/biographer engaged in mirror talk with her own characters, authentication is beyond her reach. Patsy develops a many-to-one web, feeding the creation of self from multiple possible protagonists.

18 Ultimately, Patsy’s diagnosis of Unbounded Narration is also her therapeutic strategy. She expresses unbounded performative creation (in a way that might be perceived as excessive, or we might just call it art) as a way of dealing with her seizures. She reclaims space and opens up new spaces through the imaginative re-performance/reliving of those experiences stripped away by memory loss, caused by the entwined factors of epilepsy and emotional trauma. Perfect Pie therefore can be read as a kunstlerroman (artist-coming-of-age story) for Patsy. But the epilepsy challenges her bardic gift: she constantly needs to carve out space, to preserve the past with words.

19 As twelve-year-olds, Patsy and Marie are forced by Patsy’s mother to hide in a closet until the lightning storm passes. But later in their lives, lightning represents power. The train is lightning and the train is power: "I stare out the window and I see just the glimpse of it, of the train speeding on to Montreal, the crash… does flash out, in my mind, like a sheet of lightning" (4). Thinking back to the way she was abused by local children, Francesca tells Patsy, "You know its funny, I stand backstage sometimes and I conjure… their faces and I am filled with a kind of electric energy, you know? And then I go out like a lightning bolt; I guess it’s revenge. I take my revenge on the stage somehow" (33). The lightning power absorbed in the crash is transmuted into an artistic power but it also flashes out in Patsy’s seizures. The stage direction accompanying her entry into seizure instructs "the lights flicker as a lightning storm" (45). In June 1996, Judith Thompson spoke about her experiences with epilepsy and the relationship of fear to the creative process. When she describes her first grand mal seizure at the age of nine, the language she uses is very similar to that she gives to Patsy to describe her seizures. Both women identify the peak moment of fear as being pulled through the floor, out of the world, into invisibility. As mentioned earlier for Patsy the fear is a sexual stalker:[h]e is pulling and pullin’ me closer… can’t breathe… Can’t breathe now and the people are so far away it’s like he is moving me under the floor, the linoleum-marble floor and under the mall and the people and into the dark the pipes and the loneliness and they are all so far away and I will die under this floor like a cockroach all my life over, all over. (51)In the next section of her speech, Thompson draws inspiration from a poem by Audre Lorde to assert that "[m]aking theatre or any kind of art is taking up space." She connects the creation of art to epilepsy, presenting both as strategies for rebelling against a restrictive mask of imposed femininity; both are ways of taking up space. After writing her first play The Crackwalker she observed that "not surprisingly I am seizure free" ("Epilepsy" 6). For Thompson, art substitutes for the seizures as an alternate way of taking up space. It is noteworthy that both Thompson and her creation Patsy describe their seizures as being removed from the world, as not being allowed to take up space. So, paradoxically, whereas the inner imaginative experience of the seizure is to be without space, the outer experience of the seizure does take up physical and social space in a decidedly unfeminine way. Like her creator, Patsy draws power from her epilepsy and the lightning even as she creates stories to fill the void that lightning creates.

20 Patsy’s nested stories of stories express a meta-auto/biographical awareness of process, each one meditating reflexively on the craft of performative storytelling, highlighting the distinct ontological status between the teller and the tale, between the artist and her art. In the early scenes of the play, woven into the conjuration of Francesca, the two women share a potent memory:PATSY. And I think of the time

FRANCESCA. that all but disappears

PATSY. We woke up.

FRANCESCA. when you wake up…

PATSY. We were both in these softy soft flannel pajamees and you woke me up and you said, "look" and I look out the window and I saw all this…

FRANCESCA. Ice.

PATSY. Glistening, Shimmering, Crystalline—

FRANCESCA. Ice. (7)

The girls run outside in their nighties and slide all over laughing and shrieking: a joyful memory. After this, Francesca materializes in Patsy’s kitchen. Out of the relived memory of the crash, Francesca realizes that in fact she saved Patsy’s life. At some point, Marie recovered her senses and tried to get off the track. But the feverish Patsy became consumed with the idea of the power of the train: "We are gonna die beautiful, we are gonna get crashed by the train and then fly through the sky" (88). Marie pulled her to safety. The adult Patsy says, "You saved my life… but you always had… saved my life, Marie. Ever since we were little girls […] Ever since you looked at me. With those eyes, like the bottom of Mud Lake. And spoke, with your mouth, all those thoughts. You

will never… know" (89). Patsy is saved by Marie, because it is Marie who makes Patsy into an artist. She is saved by her art. As she says, remembering Marie and the magical unexpected ice, "you woke me up and you said, ‘look’" (7).

21 Patsy’s potential cure lies not in the revelation of an objectively verifiable historical truth but rather in the pie-making, theatre-making, self-making process of continued reiterative storytelling. For Patsy, her location in an already fictive world precludes access to any kind of worlda truth. And so this displacement of memory recovery shifts focus to the ongoing process of imaginative creation:Dysnarrativias highlight why narrative is the fundamental mode of organizing human experience. Narrative framing of the past allows predictions of the future; generating imaginary narratives allows the individual to safely (through internal fictions) explore the varied consequences of multitudinous response options. (Young and Saver 78)Performance is an external variation on this same kind of imaginative exploration of the "what if?" scenario. Patsy cannot have auto/biography; for her it is not a noun. Rather auto/biography describes the action of the story of the story. As an ongoing verb, it reaches into the future. Likewise procedural memory is also future-oriented, as one follows the steps of a process moving forward to some end. In the end, Patsy projects this kind of future arising out of repeated process of artistic creation and exploration: "I’ll be sitting here six months from now and making pastry" (91) and making her friend once again. Through performative auto/biography, Patsy reconciles the present tense and future-oriented author-subject of auto/biography with the creation of a historically-limited protagonist, accepting both to be mutually contingent and fluid works-in-progress

Works Cited

Barr, William. "Types of Memory Problems." Epilepsy.com. Web. 18 February 2008. <http://www.epilepsy.com/articles/ar_1063660416 15 Sept 2003>.

Brewer, William F. "What is Autobiographical Memory?" Rubin 25-49.

Bruner, Jerome. "Life as Narrative." Social Research 54.1 (1987): 11-32. Print.

Caruth, Cathy. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1996. Print.

Crovitz, Herbert F. "Loss and Recovery of Autobiographical Memory after Head Injury." Rubin 273-290.

Egan, Susanna. Mirror Talk: Genres of Crisis in Contemporary Autobiography. Chapel Hill & London: U of North Carolina P, 1999. Print.

Eakin, Paul John. How Our Lives Became Stories: Making Selves. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1999. Print.

Grace, Sherrill. "Performing the Auto/Biographical Pact: Towards a Theory of Identity in Performance." Tracing the Autobiographical. Ed. Marlene Kadar. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2005. 65-79. Print.

Goodman, Nelson. Ways of Worldmaking. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1978. Print.

Knowles, Ric. "Documemory, Autobiology and the Utopian Performative in Canadian Autobiographical Solo Performance." Theatre and Autobiography: Writing and Performing Lives in Theory and Practice. Ed. Sherrill Grace and Jerry Wasserman.Vancouver: Talon, 2006. 49-71. Print.

Lejeune, Philippe. "The Autobiographical Pact (bis)." On Autobiography. Ed. Paul John Eakin. Trans. Katherine Leavy. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1989. 119-137. Print.

Moser, Marlene. "Identities of Ambivalence: Judith Thompson’s Perfect Pie." Theatre Research in Canada 27.1 (2006): 81-99. Print.

Neisser, Ulric. "Five Kinds of Self-Knowledge." Philosophical Psychology 1.1 (1988): 35-59. Print.

Nelson, Katherine. "The Ontogeny of Memory for Real Events." Remembering Reconsidered: Ecological and Traditional Approaches to the Study of Memory. Ed. Ulric Neisser and E. Winograd. New York: Cambridge UP, 1988. 244-276. Print.

Nunn, Robert. "Crackwalking: Judith Thompson’s Marginal Characters." Siting the Other: Re-visions of Marginality in Australian and English-Canadian Drama. Ed. Marc Maufort and Franca Bellarsi. New York: Peter Lang, 2001. 311-323. Print.

Ochs, Elinor, and Lisa Capps. "Narrating the Self." Annual Review of Anthropology 25 (1996): 19-43. Print.

Rubin, David C., ed. Autobiographical Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1986. Print.

Theatre Passe Muraille. The Farm Show: A collective creation. Toronto: Coach House, 1976. Print.

Thompson, Judith. "Epilepsy & the Snake: Fear in the Creative Process." Canadian Theatre Review 89 (1996): 4-7. Print.

— . "Perfect Pie." Solo. Ed. Jason Sherman. Toronto: Coach House, 1994. 163-171. Print.

— . Perfect Pie. Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 1999. Print.

Yanco, Richard J., ed. "Three children sliding on the ice." Mother Goose Rhymes. Web. 8 July 2009. <www.amherst.edu/~rjyanco94/literature/mothergoose/rhymes>.

Young, Kay, and Jeffrey L. Saver. "The Neurology of Narrative." SubStance 94/95 (2001): 72-84. Print.

Notes

Upon a summer’s day,

As it fell out, they all fell in,

The rest they ran away.

Now had these children been at home,

Or sliding on dry ground,

Ten thousand pounds to one penny

They had not all been drowned.

You parents all that children have,

And you that have got none,

If you would have them safe abroad,

Pray keep them safe at home. (Yanco)