Articles

Sickness and Sexuality:

Feminism and the Female Body in Age of Arousal and Chronic

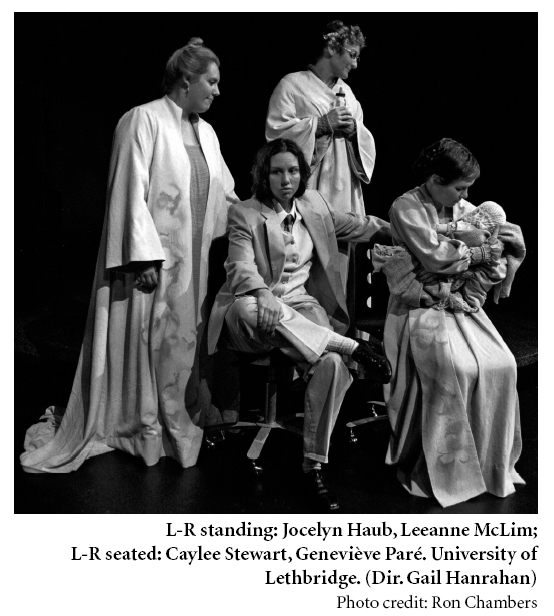

Shelley ScottUniversity of Lethbridge

Abstract

A close comparison between two of Linda Griffiths’s most recent plays yields an inter-textual exploration of the relationship between feminism, female sexuality, and medical conceptualizations of the female body. Chronic premiered in Toronto at the Factory Theatre in January of 2003, and Age of Arousal premiered in Calgary at the Alberta Theatre Projects playRites Festival in February 2007. It is the task of this paper to bring together the seemingly contradictory preoccupations of these two plays— female incapacity and female sexual power—and to show how they are fundamental to Griffiths’s larger investigation of the female body as a site of social conflict. In both their nineteenth-and twenty-first-century contexts, the plays explore changing gender roles, notions of a modern self, and ideas of female power, as they are experienced and expressed physically.Résumé

Un examen attentif de deux récentes pièces signées par Linda Griffith mène à une exploration intertextuelle du rapport qu’entretiennent le féminisme, la sexualité féminine et les conceptualisations médicales du corps de la femme. La première de Chronic a eu lieu au Factory Theatre de Toronto en janvier 2003 et celle de Age of Arousal a eu lieu au playRites Festival de Alberta Theatre Projects à Calgary en février 2007. Cet article a pour objectif d’examiner les préoccupations de prime abord contradictoires de ces deux pièces— l’incapacité de la femme et son pouvoir sexuel—pour montrer qu’elles sont essentielles à l’exploration que fait Griffiths du corps de la femme comme site de conflit social. Dans leurs contextes historiques respectifs—les dix-neuvième et vingt-et-unième siècles respectivement—, les pièces explorent l’évolution des rôles de la femme et de l’homme, les notions d’un soi moderne et les idées associées au pouvoir de la femme telles qu’elles sont vécues et exprimées physiquement.1 Aclose comparison between two of Linda Griffiths’s most recent plays, Chronic and Age of Arousal, yields a surprisingly rich, inter-textual exploration of the relationship between feminism, female sexuality, and a certain medical conceptualization of the female body. In my 2000 review of Griffiths’s plays, I noted that "[Griffiths] is fascinated with the epic, with larger-than-life characters that allow us to grapple with their relevance to our lives" (Scott 84). Her characters are always struggling to have some larger significance, each within her own context; she "draws connections between the particularities of her character’s situation and its larger resonances and implications" (Scott 88). Griffiths acknowledges this common thread when she explains, "My concentration on the sexual lives of women in Age of Arousal is part of a continuing exploration of the relationship between sex, politics and emotions" ("Flagrantly" 137).

2 The exploration in Chronic and Age of Arousal is rooted in an intense preoccupation with the female body as a site of social conflict, beginning with the spectre of sickness and its etiology, whether somatic, psychological, or social. In the nineteenth century of Age of Arousal, women are socially defined by their "natural" reproductive role, which, it is believed, makes them vulnerable on many levels and susceptible to nervous conditions and diseases. In the twenty-first century of Chronic, the central female character is well aware of this historical dismissal of a woman’s right to understand her own body and the denigration of her perspective, and she thus feels entitled to demand a biological rather than a psychological explanation for her mysterious ailment. In both contexts, the meaning of the personal experience is inextricably social. As Rebecca Hyman has argued in reference to the feminist response to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), "the rhetoric surrounding nervous disease cannot be detached from larger debates about the modern self" (189). The notion of a modern self, particularly the self as expressed and experienced physically, leads in both plays to a seemingly contradictory pairing: the power of illness and the power of sexual agency. It is the task of this paper to bring these two strands together and to examine the larger social implications of what Griffiths seems to be working through with her characters. Through the example of Chronic and Age of Arousal, these two threads—female incapacity and female sexual power—are considered as potential obstacles to the possibility of alliances between women.

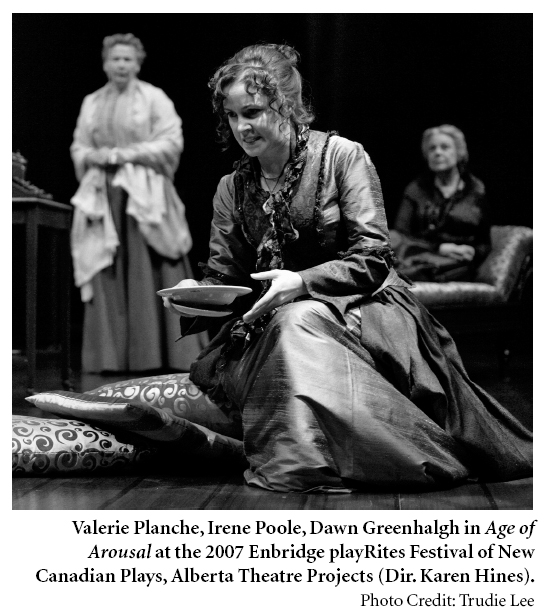

3 Chronic, which premiered in Toronto at the Factory Theatre in January of 2003, and Age of Arousal, which premiered in Calgary at the Alberta Theatre Projects playRites Festival in February 2007, would not appear to have much in common.1 However, Griffiths’s plays all tend to have certain points of comparison, particular thematic elements that run through her whole body of work. For example, in his introduction to Chronic, Jerry Wasserman compares it to the play before, Alien Creature, in 1999. While Wasserman cautions, "I don’t want to push these parallels too hard," he notes that "[a]long with the virtuoso writing that characterizes all her plays appear certain common structural and thematic qualities." For example, "her central figure is almost always a woman engaged in a struggle for power" (iii). In Chronic and Age of Arousal, the central characters in each play, Petra and Rhoda, are single women in their mid-thirties, engaged in white-collar professions dominated by men—in Rhoda’s nineteenth-century context, the secretarial world, and in our own, the high tech realm of computer programming. Their struggle for economic independence, in a non-traditional field and in a changing social climate, is key to both plays.

4 Chronic is set in an unnamed urban centre that one might assume to be Toronto, particularly given the centrality of that city to the high tech "dot com" phenomenon of the 1990s.2 To quote Wasserman in his introductory essay, the time period is "the apocalyptic twenty-first century where new diseases spawn, for which there are no cures, and overburdened systems fail" (iv). In her Playwright’s Note, Griffiths says, "‘It is the age of the virus,’ meaning things propagate quickly now, they can spread with the touch of a key" (Chronic 2). The metaphoric slippage between human and computer viruses is deliberate. Her central character is Petra, formerly a high-powered web designer, now plagued by CFS, who seeks a cure through relationships with her co-workers, her doctor, and a personification of the Virus that may or may not be causing her illness. The Virus, played in the premiere by Eric Peterson, is, in Wasserman’s description, the "smartest, nastiest, sexiest, scariest character in the play" (ii).

5 Age of Arousal, on the other hand, is set in London, England in the year 1885, although, according to Griffiths, the play doesn’t happen "in historical reality but in a fabulist construct—an idea, a dream of Victorian England" ("Playwright’s Note" 12). Although Age of Arousal was inspired by the novel The Odd Women by George Gissing (1893), Griffiths says that her "own research on the women’s suffrage movement and the Victorian age took precedence over the novel" (9). Here the central character is Rhoda, a New Woman who runs a secretarial school with her lover, Mary, a heroine and martyr of the suffrage movement. While the play is set in 1885, Griffiths notes that it encompasses "important points in Britain’s struggle for women’s rights" that happened over a period of forty-five years, from 1869 to 1914. As in Chronic, her focus is visceral:I wanted women’s violence—educated ladies of the middle and upper classes jailed with rats, shitting into buckets, smashing windows, setting fire to buildings, destroying delicate orchids. Women by the hundreds thrown into prison and tortured. ("Flagrantly" 136)If the surprising device in Chronic is the personified Virus character, here it is a technique that Griffiths calls "thoughtspeak," the external vocalization of subtext: in the midst of otherwise realistic dialogue, suddenly "characters speak their thoughts in wild uncensored outpourings" ("Production" 13).3

6 In the extensive notes and essay that accompany the published version of Age of Arousal, further justification is provided for considering its Victorian subject matter through the lens of contemporary concerns. In his Foreword, Layne Coleman suggests, "Linda has chosen the Victorian age as the ship that will carry her richest cargo, and she has chosen well. This age is the one Linda would be most comfortable in. But this is not a look back in time. This play is a cry to race towards the present" (6).The play may be about another age "but inside it is an age remarkably like your own, an age when women have to fight for everything" (6-7). In discussing the importance of costumes in her Production Notes, Griffiths comments,Unlike Shaw, Chekhov, or Strindberg, Age of Arousal is a contemporary play set in the past. How to remind the audience of this modernity without overly commenting or losing the sense of period? [. . .] Any time a costume can have a more sensual feel, go for it, regardless of perfect period detail. (18)Similarly, in describing the furniture for the Calgary premiere, Griffiths explains that the designers aimed for a sense of lightness and chose colours that we would consider fashionable today. The Remington typewriters, which play a central part in the play’s action, were placed on separate, moveable tables and Griffiths suggests that in future productions, they could "even be metal computer tables, bringing the concept of the modern to the furniture as well" (17).4 Most importantly, after conducting research into the early women’s movement and reading books by Betty Freidan, Germaine Greer, and Kate Millett for the first time,5 Griffiths concluded, "Above all, I saw that the suffragettes were frighteningly contemporary" (137). It was a familiarity that also resonated with reviewers: for example, on CBC Radio, Sharon Pollock commented, "Sometimes there’s an explosion of voices with all the women talking at once, which reminds me so much of the kitchen in my daughter’s house with all my five daughters talking at once" (Pollock).

Valerie Planche, Irene Poole, Dawn Greenhalgh in Age of Arousal at the 2007 Enbridge playRites Festival of New Canadian Plays, Alberta Theatre Projects (Dir. Karen Hines).

Display large image of Figure 1

7 The thematic elements common to both Chronic and Age of Arousal all have to do with attitudes towards sexuality and the female body, aligning both plays with typical feminist concerns. It is immediately intriguing to speculate on the potential differences arising from the plays’ time periods: the suffrage movement is considered to be the First Wave of feminism, while the 1960s through the early 1980s was the Second Wave, and we are currently in the Third. Identity, representation, and cultural production are issues particularly pertinent to Third Wave feminism, a movement which is sometimes criticized for its preoccupation with personal choice, popular culture, and sexual freedom. In this construction, a supposedly unified feminist agenda of the earlier Waves has been fragmented by an individualized feminism, nearly unrecognizable to those earlier, more serious struggles.6 But Age of Arousal refutes this construction. What Griffiths accomplishes in Age of Arousal is a kind of reversal, taking us back to the First Wave with a cast of characters that are as passionate, contradictory, rebellious, and sexually aware as we might imagine ourselves to be in the Third Wave. While Chronic gives us the dilemmas of a contemporary woman with very contemporary problems, Age of Arousal reminds us of their earlier incarnations and asks us how far we have come.

Hysteria and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

8 In her books Sexual Anarchy and Hystories, Elaine Showalter points out that part of the response to women’s emancipation, in both the Victorian period and in our own, is a complex relationship with illness. The New Woman was seen as a nervous woman: "Doctors linked what they saw as an epidemic of nervous disorders including anorexia, neurasthenia, and hysteria with the changes in women’s aspirations. Women’s conflicts over using their gifts, moreover, would doom them to lives of nervous illness" (Sexual 40). In her controversial 1997 book, Hystories, Showalter argued that many contemporary illnesses, including CFS, are new manifestations of what was, in the Victorian period, termed hysteria.

9 Showalter is interested in what she calls "individual hysterias connecting with modern social movements to produce psychological epidemics" (Hystories 3). As an example of an illness being identified with an era, she offers, "A number of historians and sociologists argued that hysteria was really a Victorian disorder, a female reaction to sexual repression and limited opportunities, which diminished with the advent of modern feminism" (4). But Showalter disagrees, showing that "[t]hroughout history, hysteria has served as a form of expression, a body language for people who otherwise might not be able to speak or even to admit what they feel" (7), so that, today, "[c]ontemporary hysterical patients blame external sources—[such as] a virus [. . .] —for psychic problems" (4). In tracing its manifestations from the Victorian to the twentieth-century woman, Showalter observes, "Hysteria is a mimetic disorder; it mimics culturally permissible expressions of distress" (15). Where once women might have fainted or developed a paralyzed limb, now the symptoms are more diffuse, but coalesce around exhaustion.

10 Just as sufferers of hysteria were emancipated New Women, the vast majority of CFS patients are white women with frantically busy lives, but Showalter claims that psychological and emotional causes are still discounted, and that "feminist accounts of chronic fatigue tend to insist on viral or neurological explanations" (Hystories 127). Not unlike the Victorian doctors that medicalized women’s discontent and thwarted ambitions into a catch-all diagnosis of hysteria, Griffiths characterizes Petra as a patient chasing a diagnosis and insisting on a physiological condition, even when her doctor is telling her the problem is her contemporary lifestyle, the pace and stress of the successful, modern woman doing it all. Perhaps the complication is to be expected for, as Showalter remarks, "Inevitably, we all live out the social stories of our time" (Hystories 6).7

Science and Medicine

11 In each of Chronic and Age of Arousal there is an early scene set in a doctor’s office. Griffiths argues in her research essay that, if there is one thing the Victorians had in common with us, it is a deep faith in the ability of science and medicine to figure things out and, eventually, to explain and cure all of our ills. In Age of Arousal, the suffrage leader Mary visits her cousin, Dr. Everard Barfoot, for her annual gynecological examination. Despite her apprehension at the prospect of the icy cold speculum, Mary says, "I tell women to be examined once yearly and I must be an example" (54). In Chronic, Petra pays a visit to her new doctor, Diane, a "regular MD" who also does alternative therapies (6). Diane is a privileged character, as only she and the Virus speak directly to the audience, and Petra is strongly attracted to them both.

12 However, in both plays the medical doctor is also compromised and suspect. At the beginning of Age of Arousal, Everard has already retired from the profession, and by the end of Chronic, Diane has been suspended for unethical conduct. Most importantly, both doctors provoke skepticism and distrust in their patients by articulating the prevailing philosophies of their respective periods.

13 Everard voices the common belief of the Victorian age, that too much intellectual stimulation will impair a woman’s fertility:EVERARD. [. . . ] there are indications that child-bearing capacities are compromised by too much thinking [. . .]. As vital energy is drawn away to support the intellect, the ovaries wither [. . .]. And as women’s nerve centres are in a greater state of instability, they are more easily deranged. (55-56)His feminist patient, Mary, and her companion Rhoda, categorically reject his simplistic idea of "inherent sexual natures." When Everard states, "you are built to bear children," Rhoda counters with, "And you are built to hunt bison" (57).

14 From our contemporary perspective, we easily scoff along with Mary and Rhoda at such unsupported Victorian theories. But in Chronic, Griffiths challenges us with an example of more contemporary medical theorizing by categorizing the alternative healing choices Petra has encountered:PETRA. I’ve had needles in my eyelids, fingers inside my anus, I’ve had cranial therapy, visceral therapy, play therapy, I’ve had my urine analysed, my saliva analysed, my feet punctured, I’ve been submerged in a tank, I’ve watched my own shit pass by me in a tube, I’ve had bear grease rubbed on my back by Native healers, I’ve been hooked up to electrodes [. . .] (3-4)Her latest doctor, Diane, believes that Petra’s problems are emotional. In explaining why Petra is suffering from her mysterious illness, Diane asserts, "There is a profile that goes with these symptoms, a majority of women with driven personalities" (5). Diane’s methods include a powerful forest visualization exercise and, at the end of the play, a kind of drama therapy experiment in which Diane and Chris, Petra’s boyfriend, play Petra’s parents in a re-enactment of her childhood trauma (60). Griffiths seems to give credence to this psychological approach: in her Playwright’s Notes she writes, "Only in nature, inner and outer, is there some balance, only in the inner forest is there light" (2). The psycho-drama appears to push Petra into a healing catharsis.

15 However, the more extreme implications of what Diane is arguing are highly problematic. Late in the play, when pushed to confess her real feelings about her patients, Diane reveals that she basically blames them for their own suffering, claiming, "Happy people don’t get sick" (40). In contrast, even while "debunking" what she sees as modern hysterias, Elaine Showalter insists, "I don’t regard hysteria as weakness, badness, feminine deceitfulness, or irresponsibility, but rather as a cultural symptom of anxiety and stress" (Hystories 9). In the Victorian age, the medicalization of sexuality was connected with the unquestioned authority of science. Ignorant of their own reproductive systems, women submitted to medical authority, which in turn decreed that their physicality rendered women incapable of being educated ("Flagrantly" 148). Griffiths makes a similar point about our own era, in which fear of new and unknown illnesses can lead to unproven diagnoses and desperate measures, especially in a climate of environmental collapse and a constant barrage of contradictory information. In that sense, it is important that both plays take place in large urban centres and evoke their association with a faster pace of living, increased stress, and an atmosphere of intense competition (for men, for jobs, for both personal and material success). Removed from the safety of rural and family traditions, Griffiths’s characters live in an environment where the gap between aspiration and economic reality is a constant presence and where the consequences of failure are dire.

L-R standing: Jocelyn Haub, Leeanne McLim; L-R seated: Caylee Stewart, Geneviève Paré. University of Lethbridge. (Dir. Gail Hanrahan)

Display large image of Figure 2

16 As Rebecca Hyman has argued, while Showalter rejects a nineteenth-century psychoanalytic interpretation of female hysteria as intrinsic to femininity, she advocates a psychological and therapeutic approach to solving the symptoms of CFS. Hyman points out that feminism has empowered women to be their own medical advocates: "They insist it is others’ preconceptions about women and disease that prevent their being taken seriously by Western medicine" (195). In this regard, Mary and Rhoda are ahead of their time and similar to Petra in their ability to reject a diagnosis that dismisses them as victims of their own feminine nature. Petra has the added advantage of a hundred years of feminist activism: she can insist to her doctor that her ailment is physical and must be acknowledged. Yet, in part because of the advocacy of feminism, those intervening hundred years have infiltrated Western medicine with a myriad of alternative therapies and healing philosophies. Ironically, Petra must now reject, not only traditional Western medicine, but also a host of "Eastern" diagnoses too.

Fainting

17 In a related but more comic vein, in each of Chronic and Age of Arousal there is a scene about women fainting. Through most of medical history, the uterus was believed to travel through the body, causing problems wherever it lodged, including fainting (Showalter, Hystories 15). In Age of Arousal, fainting is presented as a romantic emblem of feminine frailty and delicacy, a way to gain attention and sympathy, and as a means to get away from unsolvable problems. In Chronic, Petra comments, "I’ve always wanted to faint," and her co-worker Amber agrees, "Me too, I used to practice fainting and saying, ‘she was never very strong’" (19). A few lines later, Petra further admits "[t]here are some advantages to being sick." Within the strange dynamic of their relationship, which is mainly one of mutual envy, Amber toys with the idea of asking the Virus to make her sick too, imagining it as being glamorous, "Like that Victorian consumptive thing," or bestowing her with a look of ecstatic martyrdom. But as the Virus starts to scream in her face, Amber changes her mind and pulls away:AMBER. I don’t think I’ve thought this out very well. I was just thinking about a fainting spell now and then. But then I could also just fake it, couldn’t I? (20)

18 In Age of Arousal, the last scene of Act One is titled "Rehearsing and Fainting." First, sisters Alice and Virginia have a heated argument that culminates in a competitive exchange:VIRGINIA. I feel faint—

ALICE. Faint, then.

VIRGINIA. I am going to faint.

ALICE. Do you think I cannot faint? I will faint first. Observe. I pant with shame and betrayal, and then …ahhh… Alice faints.

VIRGINIA. Shame and betrayal? I faint from the weighty chains of sisterly love! Ahhhhhh! — Virginia faints. (86-87)

Their beautiful young sister Monica sneers, "Why faint at all if there’s no man to catch you?", while the feminist Rhoda offers a practical assessment: "We faint because our corsets are too tight, we faint because we’re encouraged to take no exercise—[. . .] Women feign weakness to barter for security which creates loneliness—" (87). But much to their surprise, the matriarch, Mary, decides to faint for the sheer physical sensation: "To sink, to flutter [. . .]. So voluptuous to be feeble—." This prompts Monica to take on the challenge, declaring "I will faint better than any of you" (87). Finally, in a comic conclusion to the first act, Rhoda is persuaded to join them all on the floor. While played for laughs in both plays, the underlying implication is that weakness, even sickness, can be an attractive alternative (or strategy) when faced with too much emotional stress.

The Female Body

19 These scenes of medical examination and fainting point to the central preoccupation in both plays—the female body and female sexuality. The significance of one’s gendered body is of profound importance to theatre, and to feminism. Sue Clegg writes,The significance of the life of the mind has been important for both First and Second Wave feminism. This is not surprising given the discursive resilience of mind/body dualism within the western philosophical canon; a dualism in which women became assigned to the swamp of the body while the masculine purity of the mind was lauded. (212)As Clegg acknowledges, the dualism of male and female roles is further complicated when fears about race and class are factored into the equation, and as individuals threaten to exceed their "natural" place in the social order.

20 Griffiths carefully unravels the contradictory Victorian attitudes about women’s sexuality in her research essay. She begins with the theory of separate spheres, the belief that woman is the "angel in the house," exerting her influence in the private realm of running the home and raising the children, untouched by the violence and politics of the public world ("Flagrantly" 140):Woman’s purity was also a societal construct to protect her from herself. It was believed by many that if the velvet chains were released from her delicate wrists, hell would break loose. Because women were ultimately physical, they were like nature itself— unpredictable, unreasonable, dangerous. Women’s passions, once unleashed, would be uncontainable, given that reason had no place in her nature. Without legal and societal boundaries, she might become sexually voracious. ("Flagrantly" 141)As Griffiths points out, this is an impossible contradiction— women are at once purely physical, natural, defined entirely by animal biology and sexual function, yet at the same time believed to be sexless, passionless, and pure, functioning as a civilizing influence on brutish men: "they weren’t supposed to like sex, unless they were unleashed, and then who knew what might happen" ("Flagrantly" 142).

21 "What might happen" is precisely the topic embodied by Monica in Age of Arousal and by Petra in Chronic, women of the First and Third Waves, both defined by their relationship to their physicality. Of Chronic, Wasserman observes that "[h]er obsession with her illness, her hyper-consciousness of her body and its symptoms, has turned Petra essentially inward" (ii). In a key scene, Petra has an argument with her doctor, Diane, about the popular conception of the "mind/body connection."8 As Diane tries to get her to talk about the emotional origins of her illness, Petra angrily mocks her phrases—like "Ask your body," and "Your body is telling you something"—as meaningless (24):PETRA. The mind/body connection is supposed to mean that my mind can tell my body not to be sick. My mind and body don’t talk have never talked will never talk to each other and neither do anybody else’s. It’s a hoax to make doctors feel better. (25)But Diane is insistent and retaliates: "I’d rather be ruled by my body than live in a virtual attic in my head" (25).

22 As its title suggests, Age of Arousal concentrates more on the struggle for women’s sexual liberation than on the right to vote. Griffiths writes that "the themes and characters of that age came bursting out of the keyboard, not as dry historical figures, but sexual and lubricious, explosive and contradictory" (8). In an imagined letter to George Gissing in which she both commends and criticizes him for his novel The Odd Women, Griffiths writes, "Even Shaw never put that many women together in the same work [. . .] I added the element of sex and I don’t think that’s inappropriate, given your first marriage [to a prostitute]" (10). Gissing himself argued that the only way for society to change "is to go through a period of what many people will call sexual anarchy" (qtd. in Spiers and Coustillas 88).

23 All of her characters are grappling with their sexuality in one way or another. Griffiths concludes that, while, "‘Victorian’ has become synonymous with ‘sexless’, ‘repressed’, and ‘joyless,’" to the contrary, they were in fact "sex-obsessed" ("Flagrantly" 139). For example, of her oldest character, the lesbian feminist Mary, Griffiths writes, "This is a hip Victorian woman and she should be dressed as interestingly and as sensually as possible" ("Production"19). Rhoda is caught between her love for Mary and her attraction to the male doctor, Everard. Virginia embraces her celibacy gladly, while Alice chooses to travel to Berlin and dress as a man. But it is the youngest sister, Monica, for whom sexuality is the greatest key to her political awakening: Griffiths writes that in costuming the actor, she should be "deliciously exposed" (18), and "lusciously attractive [. . .] like a piece of confectionary candy" ("Production" 20).

24 The portrayal of Monica is the biggest difference between the play and the original novel. In the novel, Monica makes an unsuitable marriage to an older man, of whom Marcia Fox writes, "Certainly he has found far more trouble than he bargained for in the simple and passive shopgirl he courted" (viii). Monica takes a young lover and suffers the stereotypical Victorian punishment of dying in childbirth. In her Introduction to Gissing’s novel, Fox laments,she plunges into an unsuitable marriage, largely for economic reasons, and becomes a virtual paradigm of the social tragedy the two feminists [Mary and Rhoda] militate against. Rebelling against the restricted domestic role of the Victorian wife, Monica nevertheless is unable to channel her revolt into anything productive or satisfying. (viii)

25 In contrast, Griffiths uses Monica to voice the philosophy of emancipation through sexual freedom, or "free lovism," as the character calls it. To her first lover, Everard, Monica proclaims, "Physical liberty is the personal expression of revolutionary change" and then continues in the "thoughtspeak" subtext "I know the glory of my quim" (93; italics in original). To her rival, Rhoda, Monica is unabashed: "Physically awakened women are a force to be reckoned with—I am beginning to see this power, to know its strength, its reality—" (113). Her sister Alice takes a much dimmer view of the value of sexual liberation: "This is the future, emancipated women claiming their bodies in order to frig as many men as they possibly can" (122). But Monica is as much a pioneer in her way as the suffragists, reforming her culture and, ultimately, our own, through her political promiscuity.

26 The topic of sexuality was, in a sense, forced into public discourse by the demographic anomaly of the Victorian period. By 1885, it was estimated there were half a million more women than men in London, creating the phenomenon of the spinster, or Odd Woman. As the character Rhoda remarks, "Women must come to grips with two things in this age. Loneliness and money" (40). The typical picture for the middle-class spinster was bleak, but Griffiths claims, "the feminist movement created a new kind of spinster—active, educated, even choosing to remain celibate. Some considered spinsterhood a political decision, a deliberate choice made in response to the conditions of sex slavery" ("Flagrantly" 146). Showalter agrees that some feminists and suffragists advocated "celibacy as a ‘silent strike’ against oppressive relations with men," while "More moderate feminists endorsed celibacy on ideological, medical, or spiritual grounds, or advocated it as a temporary political strategy" (Sexual 22). According to Griffiths, other spinsters "explored their sexuality, taking enormous chances, determined to find a way for their sexual selves to be a part of an expanding consciousness" ("Flagrantly" 146).

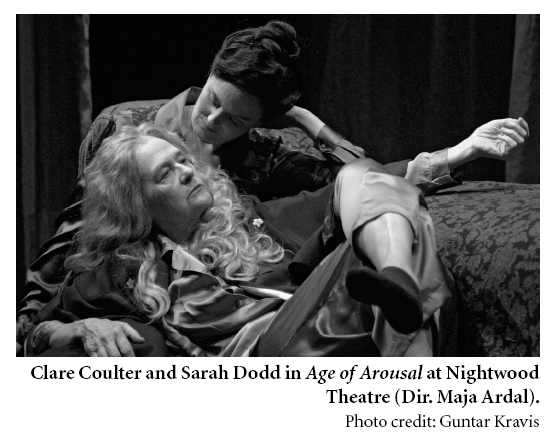

27 Both Age of Arousal and Chronic also explore the theme of lesbian sexuality. In her research essay for Age of Arousal, Griffiths discusses "passionate friendships" between women, some of which were sexual and others not. While male homosexuality was criminal in Victorian England, lesbian behaviour was classified as a sickness because "for women to initiate sexual action without prompting from a male is not only unnatural but physically unhealthy" ("Flagrantly" 147). The play begins with Mary and Rhoda as lovers. Their sexual relationship ends when they quarrel over how to run the school and as Rhoda finds herself passionately attracted to Everard. In the end, however, Rhoda chooses a non-sexual destiny, turning Everard down and remaining with Mary as business partners and friends.

28 In Chronic, Petra and her co-worker Amber have an erotic encounter when Amber bathes Petra. However, Petra turns down the prospect of a relationship, saying, "I don’t need any more attention" (50), and advises Amber to pursue their boss, Oscar, instead. Wasserman writes of Petra that "She has no circle of girlfriends nor systems of family support so it doesn’t seem completely strange that she should find herself drawn to other women." Of Amber, Wasserman remarks, "A sexed-up bubble-head who is after Petra’s job, she develops surprising empathy for her rival and becomes another key element in the complex symbioses that comprise Petra’s life" (ii). A Third Wave reading of Amber would suggest a young woman entirely comfortable with her sexuality and would characterize her adventurousness with Petra as a disavowal of old-fashioned binary labels. In fact, one could even argue that Amber unleashes Petra and sets her on the course that will ultimately cure her. After her encounter with Amber, Petra next propositions Diane, who responds by admitting that she slept with Chris, Petra’s boyfriend. Rather than destroy any of these relationships, however, the admissions seem to lead to a breakthrough, as Diane and Chris re-enact Petra’s parents’ abusive dynamic and lead her to what appears to be an emotional catharsis (60).

Clare Coulter and Sarah Dodd in Age of Arousal at Nightwood Theatre (Dir. Maja Ardal).

Display large image of Figure 3

29 Leslie Heywood and Jennifer Drake, the editors of Third Wave Agenda, maintain that the biggest difference between Second and Third Wave feminism is a Third Wave comfort with contradiction and pluralism. Amber’s choices, like Monica’s, may not look like stereotypical feminism, but both characters ultimately prove that their loyalties lie with other women.

Between Women

30 Ultimately, it is the complex and sometimes antagonistic relationships between women in both these plays that make them most Third Wave in their feminism. When Amber brings Petra a gift and says she is trying to be friendly, Petra observes, "I’ve always thought people with lots of friends were kind of gross" (15). Amber, in turn, acknowledges that, in her competition with Petra, her stereotypical attractiveness might actually work against her. When trying to decide which woman to fire, their boss, Oscar, reassures Amber: "Beautiful girls can go places, people with big businesses want beautiful girls." Amber responds, "You know, Oscar, beautiful doesn’t get you bupkas anymore. Beautiful can turn against you these days" (51).

31 In Age of Arousal, Everard is attracted more to plain Rhoda, or even to his older cousin Mary, than to beautiful young Monica:EVERARD. [. . .] that pretty girl in the park was very sweet, but women like this, old and young, hawkish and proud, the thought of lifting their skirts and seeking out the moist folds beneath, of bringing brilliant heady women to their knees moaning, grasping at me— (60)In fact, in both Gissing’s novel and Griffiths’s play, Monica’s desirability eventually traps her: in both she becomes pregnant and dies in childbirth. In the play, Monica and Rhoda admit being jealous of each other and wish they could have been friends, but Rhoda is the one with energy and hope for the future, while Monica somehow knows she will need to be sacrificed so the other women can raise her child (126).

32 Each wave of feminism has been about choices for women, often won through the pleasures and hazards of female friendship. As

Alice says, "The bonds between women are laughable to the world, but they are marriages in a sense, and they may be betrayed" (111). Most explicitly, Third Wave feminism has not been afraid to address questions of conflict between women, particularly when conflict arises over differing opinions of what constitute good choices. This is summed up in a confrontational way between Mary and Rhoda, as they debate bringing in new pupils to their school:RHODA. I shouldn’t have invited them. Suddenly I hate them—

MARY. Then you hate women, then our struggle is for nothing.

RHODA. So sick of prompting and praising, only to have them put the shackles back on their own wrists. (50)

Griffiths acknowledges an acute awareness of these issues when she writes of her subject matter: "Here were the contradictions, hypocrisies and bizarre scenarios of the sex war. I felt it was a good time to admit all the flaws of the struggle while still popping the champagne" ("Flagrantly" 166). Griffiths herself ends her essay on a surprisingly ambivalent note, with an anecdote about her own reluctance to embrace the feminist label (166).9

Conclusion

33 Intriguingly, that ambivalence is directly reflected in the real-life feminist discourse around nervous disease. In her article on CFS, Hyman concludes that, in the narratives of the women who believe they suffer from this disease, there is a strong subtext that blames feminism for making women believe they could "have it all"— beauty and fitness, a marriage and children, and a fulfilling career. Hyman writes of "the implicit blame placed on feminism for creating a social order that causes and exacerbates nervous disease," and that "CFS patients see the feminist agenda as in part responsible for their breakdown in health" (197). The most successful cure for CFS has proven to be "the 50% solution," a prescription to cut the victim’s previous activity level in half and simply do less (198), which Hyman believes proves her contention that the nervous disease has a social cause. It is neither biological nor a result of personal psychology, but rather a reaction to "a world we created that makes people sick" (199).

34 What brings these two plays together is Griffiths’s understanding of the way issues continue to resonate, still unresolved, from the awakening Victorians to the conflicted couples of today:These are our ancestors. These long-forgotten laws continue to have an impact on us. Behaviours and beliefs echo for generations after, reverberating into the perfect condos of young married couples, sneaking into the air systems of family homes, polluting the atmosphere as we all attempt the oh-so-delicate balance of love, sex and the outside world. ("Flagrantly" 145)In her study Sexual Anarchy, Elaine Showalter compares the Victorian Odd Women phenomenon to late-twentieth-century magazine articles that warn women of the likelihood of spinster-hood the longer they wait to marry. The message of such articles seems to be that "[t]he sexual anarchy of women seeking higher education, serious careers, and egalitarian spouses [. . .] engendered its own punishment" (35). With Age of Arousal, Griffiths makes clear that the revolution has been a long time in the making, but in Chronic, she suggests that we have still not come to grips with how to live with all its implications. One disturbing implication is that feminism has actually done women a disservice by putting too much emphasis on achievement. The promise of sexual liberation is a powerful tool, but also an emotional and biological trap (as in the cautionary case of Monica). Competition and jealousy threaten real alliances between women in both plays. Can women really respect other women who have made different choices? These are explosive issues, not fully resolved in either play. It is a testament to the imaginative power of the plays that they offer tentatively hopeful visions for reconciliation, but the more troubling interpretations remain.

Works Cited

Bruns, Cindy M., and Colleen Trimble. "Rising Tide: Taking our Place as Young Feminist Pyschologists." The Next Generation: Third Wave Feminism Psychotherapy. Ed. Ellyn Kaschak. New York: Haworth, 2001. 19-36. Print.

Clegg, Sue. "Feminities/masculinities and a Sense of Self: Thinking Gendered Academic Identities and the Intellectual Self." Gender and Education 20.3 (2008): 209-221. Print.

Coleman, Layne. "Foreword." Griffiths, Age 6-7.

Fox, Marcia R. "Introduction." The Odd Women. By George Gissing. 1893. New York: Norton, 1977. i-viii. Print.

Gamble, Sarah, ed. The Routledge Companion to Feminism and Postfeminism. London and New York: Routledge, 2001. Print.

Gissing, George. The Odd Women. 1893. Ed. Arlene Young. Peterborough: Broadview, 1998. Print.

Griffths, Linda. Age of Arousal. Toronto: Coach House, 2007. Print.

— . Chronic. Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 2003. Print.

— . "A Flagrantly Weird Age: A reaction to research, time travel and the history of the suffragettes." Griffiths, Age 136-168.

— . "Playwright‘s Note." Griffiths, Age 8-12.

— . "Production." Griffiths, Age 13-22.

Heywood, Leslie, and Jennifer Drake. Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminism. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1997. Print.

Hyman, Rebecca. "Vampire of the body: The politics of chronic fatigue syndrome." Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 11.1 (1991): 187-201. Print.

Johnston, Kirsty. "Review of Chronic." Canadian Literature 191 (Winter 2006):147-148. Print.

Kamen, Paula. Her Way: Young Women Remake the Sexual Revolution. New York: New York UP, 2000. Print.

Kaplan, Jon. "Hot Stuff for the Cold Season," NOW Magazine 22.18 (2003): n.p.Web.

— . "Thin Script," NOW Magazine 22.20 (2003): n.p.Web.

Pollock, Sharon. The Homestretch. CBC Radio: Calgary. February 2007. Radio.

"Age of Arousal." Enbridge playRites Festival. Program. 31 January-4 March, 2007. 8-9. Print.

Richardson, Elaina. "What is Your Body Trying to Tell You?" O: The Oprah Magazine (2008): 122-127. Print.

Scott, Shelley. "Review: Sheer Nerve: Seven Plays." Theatre Research in Canada 21.1 (2000): 84-89. Print.

Showalter, Elaine. Hystories: Hysterical Epidemics and Modern Media. New York: Columbia UP, 1997. Print.

— . Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the Fin de Siècle. New York: Viking, 1990. Print.

Spiers, John, and Pierre Coustillas. The Rediscovery of George Gissing: A Reader’s Guide. London: National Book League, 1971. Print.

Wasserman, Jerry. "Alien Creatures and the Ecology of Illness: Linda Griffiths’ Chronic." Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 2003. i-iv. Print.

Notes