Articles

Two Patterns of Touring in Canada:

1896 To 1914

Anthony VickeryUniversity of Victoria

Abstract

In the period immediately preceding the First World War, cities in Canada were regular stops on the commercial touring system. Companies were sent out from New York by major producers and integrated two types of stops into their routes—those booked directly by the producers and those booked via entrepreneurs who operated their own circuits of theatres. Entertainments Ltd., a corporation with both New York owners, the Shubert brothers, and a Canadian owner, Lawrence Solman, operated the Royal Alexandra in Toronto which is given as an example of a directly controlled theatre. Ambrose Small’s group of theatres covering stops in Ontario is given as an example of circuit-booked theatres. Producers in this era had to integrate both types of stops into their schedules to achieve full touring schedules and maintain the profitability of their companies.Résumé

Juste avant la Première Guerre mondiale, plusieurs villes canadiennes figuraient régulièrement sur le circuit des tournées commerciales. Des compagnies y étaient envoyées depuis New York par de grands producteurs, et leur itinéraire comptait deux types d’arrêts — ceux qu’avaient réservé les producteurs directement et ceux que retenaient des entrepreneurs gérant leurs propres circuits de théâtres. Entertainments Ltd., une compagnie qui appartenait à deux New-Yorkais, les frères Shubert, et à un Canadien, Lawrence Solman, exploitait le Royal Alexandra de Toronto, qui est cité en exemple d’un théâtre contrôlé directement. Le cas d’Ambrose Small, qui gérait une série de théâtres en Ontario, est un exemple de théâtres réservés par circuit. Les producteurs de l’époque devaient faire appel aux deux types d’arrêts pour remplir les horaires de tournée et veiller à la rentabilité de leurs compagnies.1 From 1896 to the First World War was the golden age for the theatrical touring in North America. Touring companies, mainly originating in New York City, crisscrossed the continent by the hundreds. While the overwhelming majority of stops were in the United States, there was also considerable activity in Canada. Both of the largest producing firms, the Syndicate and the Shuberts, sent companies across the border into theatres from Montreal westwards. Stops the road companies played fell into two basic categories: theatres controlled by New York producers and theatres on circuits run by local entrepreneurs. To maintain profitability, the producers in New York balanced both types of bookings throughout the era.

2 The theatres in the first group, usually in major cities, were directly controlled by the firms in New York, through either direct ownership or long-term operating agreements. The New York producers were responsible for the operation of the theatre,usually by employing a local representative. Second, there were circuits of theatres in smaller centres assembled into a series of connected dates by a local entrepreneur. The New York producers would contract the local businessman on a show-by-show basis to send their companies over a portion or all of the circuit. The local circuit operator would look after the operation of the theatres, with the producers only supplying the attractions. While direct control provided a simpler relationship between theatres and producers, including easier booking as well as higher potential profits, it also exposed the producers to higher financial risk and usually more extensive initial costs. On the other hand, booking arrangements with independent circuits required little initial financial outlay, but gave the producers less control over their routes and introduced an element of negotiation into the booking arrangements, which could be problematic if the personalities involved were difficult. Both systems more or less equally shared in the presentation of theatrical performances during the era.

3 This article will explain the two patterns of touring using examples from Ontario in the period 1900 to 1918. The first section will examine direct control from the perspective of the Shubert Theatrical Company and its investment in Entertainments Ltd., an Ontario corporation that operated the Royal Alexandra Theatre in Toronto and later the Princess Theatre in Montreal. The second section of the article will shift to the circuit operated by Ambrose Small, also located in Ontario. Both of the above sections will explore the contractual and financial relationships between New York and the theatres in Canada as well as the procedures for booking companies on the road. Finally, a reconstructed touring schedule for the Shubert production of The Kiss Waltz in 1912 will provide an example of how a producer integrated both types of stops into a production’s route.

4 This article builds on the foundations provided by Alfred Bernheim’s The Business of Theatre: An Economic History of the American Theatre, 1750-1932 (originally printed in 1932) and Jack Poggi’s Theatre in America: The Impact of Economic Forces, 1870-1967 (1968)1 by rendering into fuller detail the difference between theatres directly controlled by the producers in New York and theatres booked via agents for circuits. While both Bernheim and Poggi analyze the theatrical marketplace at a high level, this paper drills down into the micro-level transactions that allowed the system to operate and examines the advantages and disadvantages of each system. Bernheim writes that the Shuberts used these two methods, but not the Syndicate. The example of Ambrose Small in this article demonstrates that the Syndicate also engaged in circuit booking.

5 By 1900, the first-class touring industry was highly developed. A company was considered "first-class" if itshall have appeared and given public performances at some theatre in the City of New York, Boston, Chicago or Buffalo or Philadelphia at which the charge for the greater portion of the orchestra seats during such performances was Two Dollars ($2.00) each in New York City or one and a half ($1.50) dollars in other cities named. (Solman, Shubert, and Shubert 22 December 1908)There were literally hundreds of companies travelling the road each year. In his seminal study The Business of the Theatre, Alfred Bernheim notes that 420 companies were on the road in the first week of December 1904 (75). While the overall number of companies declined after that season, there were still approximately forty-one companies on the road around the end of the First World War in 1918 (75). Typically these companies toured from September to June each year depending on how long they remained profitable. Their touring routes were made up of stops of various lengths relative to the city’s potential audience. In general, companies stayed in a city for one, three, or six nights (with matinees typically on Wednesdays and Saturdays). Toronto’s population in 1901 was 208,040 (City of Toronto Archives) and the city was generally a sixday stop, while the rest of the cities and towns in Ontario were one-night stands (although Ottawa and Hamilton would sometimes host productions for more than one night). Indeed, the majority of North American stops were one-night stands (numbering at any time between 300 and 500 theatres continent-wide). Breaking up the travel between the larger centres with one-night stands was an economic necessity as travel expenses formed a significant portion of total costs, so companies were routed to play eight shows a week to maximize potential revenue. This schedule required that individual stops be no more than six or seven hours apart by rail so the company could easily move to the next city, set-up, and be in a position to mount a performance the next evening. The circuits controlled by local businessmen tended to be comprised mainly of one-night stands, while theatres that were directly controlled were usually three-night or week-long stops.

Entertainments, Ltd. and Shubert Involvement in Canada

6 In 1908, the Shuberts, along with Canadian businessman Lawrence Solman, formed Entertainments Ltd. to control the operations of the Royal Alexandra Theatre in Toronto directly. The Royal Alexandra was originally constructed by local businessmen led by Cawthra Mulock. The ownership group approached the Syndicate originally about a booking contract, but was rebuffed (O’Neill 39). A contact between the Shuberts and Solman covering booking was signed on 13 March 1906, but not put into effect. According to Mora O’Neill in her history of the Royal Alexandra, the Shuberts did not begin to supply road companies to the theatre until 1909 (107). These companies operated under the contract signed on 22 December 1908 between Solman, the Shubert Theatrical Company, and the Shubert brothers themselves. The contract set out the terms for the foundation of Entertainments Ltd. in which Solman contributed $5,100 for 51% of the stock of the company and the Shubert brothers contributed $4,900 for the remaining 49%. The contract also formed an agreement between Entertainments Ltd. and the Shubert Theatrical Company to act as booking agent for the theatre and to supply enough attractions to fill 25 playing weeks.2

7 The agreement contained a number of financial clauses governing the new company. Entertainments Ltd. was to acquire the lease of the Royal Alexandra from its owners at a rate of $20,000 per year. The agreement also stipulated that for each week the Shuberts failed to provide attractions to the theatre, they were to pay to Solman damages of $1,000. Solman was also free to book the theatre in that period and the Shuberts were not entitled to recover any of the damages if he was successful in obtaining replacements (though of course, as part owners, they would get their share of the profits on the engagements). These liabilities (or potential liabilities) were the main factors that separated direct ownership from circuit booking. To begin operation, the Shuberts had to contribute capital to the project and commit to having a certain amount of capital tied up in the company to service its expenses. Since they were also liable to damages, they had to be sure to supply enough companies to the theatre, even if the engagements were not particularly profitable.

8 There were two other financial clauses in the original contract. The first names Solman as resident theatre manager in Toronto at a salary of $100 per week. Finally, the company was required to pay a dividend of 75% of the annual profits to the shareholders each year. These financial clauses were further amended by a contract between Solman, the Shuberts, and Entertainments Ltd. on 13 January 1909 setting the on-hand cash capital of the company at $10,000. If the company sustained an operating loss in any particular week, the Shuberts were to contribute half of the loss and Solman the other half to maintain on-hand cash at $10,000.

9 On 24 April 1909, the agreement was amended to add a lease on the Princess Theatre in Montreal to the assets of Entertainments Ltd. (Canadian), and a later agreement created a booking arrangement between the Princess Theatre and the Shubert Theatrical Company on much the same terms as set for the Royal Alexandra with the exception of the damages for lost weeks (Shubert Theatrical). The April agreement set the rental for the Princess at $22,500 per year plus 10% of the annual profits of the theatre. The lease was for an initial period of five years and was renewed in 1914. However, due to dismal business, Entertainments Ltd. assigned the lease to the Canadian United Theatres to use as a vaudeville house in 1916 (Entertainments). Clause 12a of this contract with Canadian United specifically prohibited the new tenants from presenting any "high-class attractions such as those booked through the Shubert and Klaw and Erlanger [the main Syndicate booking firm] offices." The Shuberts and the Syndicate had an unofficial agreement between 1913 and 1917 to lessen competition in centres where the volume of business did not justify two theatres (Bernheim 70-1). This truce explains the clause prohibiting the use of the Princess as a legitimate house.

10 Typically, touring companies and local theatres split the box office on a percentage basis nightly. There were exceptions when a local theatre could offer a guarantee to a company for a certain amount and keep all the takings at the box office (the local manager thereby taking the risk for the show’s success in the hopes of garnering a larger profit if the production were popular). However, a more common scenario saw the company keep between 70% to 85% of the gross box office and the theatre take the residual amount. The company was responsible for maintaining the production and paying the performers and therefore incurred the majority of the expenses. Large-cast musicals or star vehicles commanded the 85/15 split. In the case of Entertainments Ltd., the Shuberts would be not only getting the profits from the company’s share (if the company was produced by them, which a large number of the companies playing the theatre would be), but also a pro rata share of the theatre’s profits.

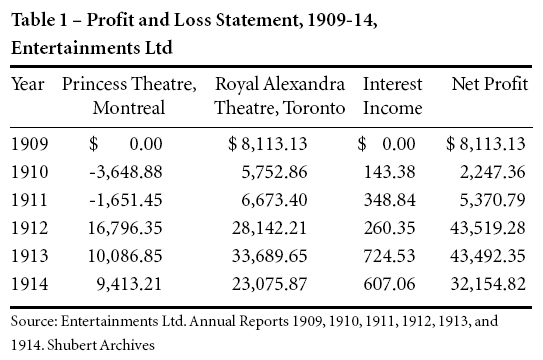

Table 1 – Profit and Loss Statement, 1909-14, Entertainments Ltd

Display large image of Table 1

11 The original December 1908 contract called for a yearly report to be distributed to shareholders at the end of the theatrical season (usually in June or July). Table 1 shows the profits for Entertainments Ltd. for the years 1909-1914.3 The Shuberts’ tenancy during these years was quite profitable for both the theatre owners and the shareholders of Entertainments Ltd. The Royal Alexandra’s first season in 1908, the year before the formation of Entertainments Ltd., might have produced a profit of approximately $8,000 (against a building cost of $750,000) (O’Neill 100).4 After Entertainments Ltd. acquired the lease, the theatre owners were relieved from any financial responsibility for the operation of the theatre and were guaranteed $20,000 per year. While this amount was not overly large, it did allow for a steady recovery of the owners’ initial investment with little risk. The Shuberts also garnered decent profits from the arrangement. Considering that the theatre itself usually received only about 30% of the box office gross, the companies booked into the theatre, including many Shubert companies, must have earned fairly good profits, especially when the earnings of Entertainments Ltd. were high ($43,519.28 in 1912 and $43,492.35 in 1913). The profits rose a good deal between the $5,370.79 of 1911 and the $43,519.28 of 1912 and then fell off shortly afterwards.

12 While Solman was in charge of the day-to-day operations at the Royal Alexandra, the Shuberts sent advice and direction from New York to Toronto. In the correspondence, the Shuberts often urged Solman to keep his costs to a minimum:Beg to acknowledge receipt of yours of the 26th inst., with reference to the curtailment of expenses at our theatre. I agree with you in everything you say and after the first of the year, I will do everything in my power to cut ours. (Solman, 31 December 1913)When business fell during the First World War, the Shuberts wrote to Solman to pressure the landlords in Toronto and Montreal to lower the rent charged for the two theatres:You must see your landlords in Montreal and tell them that they must reduce the rent for the coming year. We cannot continue to pay this rent [. . .]. While on the subject, we wish you would see the people in Toronto. They must reduce their rent pending this war condition. We cannot go on losing money. (J.J. Shubert, 28 June 1915)The tone of this letter is more akin to active direction rather than passive advice.

13 When Entertainments Ltd. first acquired the Princess Theatre in Montreal, the Shuberts took a very active role in readying the theatre for use. The following letter to their local manager, George S. McLeish, shows that they were actively engaged, but gave some latitude to the man on the spot:I wish you would please carefully go over matters in connection with the engagement of the house staff as we talked and retain no one who in your estimation is not of the calibre you desire. Please do not fail to outline to me fully as soon after your arrival as possible the conditions as they exist regarding the theatre and everything appertaining to it. (Bird, 21 July 1909)5In common with local managers in all parts of the United States and Canada, McLeish was advised on a number of occasions that goods could be procured much more cheaply in New York:Of course the price charged for the sign, the drawing of which you submitted me, is entirely out of the question. I could have the same sign built in New York for less that one-half the money. (Bird, 9 August 1909)This type of letter crops up quite frequently in General Manager Charles Bird’s correspondence to all parts of the continent covering theatre supplies such as heating coal, signage, and labour costs. The Shubert head office also set the ticket prices to be charged: "I am herewith returning to you diagram [sic], together with your list of prices, which you will observe have been altered in a measure by Mr. Shubert. Kindly follow these prices in all instances" (Bird, 11 August 1909). This level of direction was in complete contrast to the way that the Shuberts dealt with their circuit booking representative in Toronto, Ambrose Small.

Ambrose Small: Circuit Booking in Ontario

14 Ambrose Small was one of the most prominent theatrical entrepreneurs of the 1896-to-1919 period in Canada. Not only did he manage to build a large fortune based on theatrical properties, but he disappeared before he had a chance to spend any of his riches. Robert Grau, writing in 1910, gave Small the lion’s share of the credit for establishing theatre as a business in Ontario (311-2). M.B. Leavitt states that Ambrose Small "founded the first successful circuit in that section of the country [Ontario] and has operated it profitably not only for himself but also for the producing manager" (567). Small’s circuit of theatres covered many small and large centres in Ontario (see Figure 1). Grau’s very positive evaluation of Small only reflected the financial success of the producer; however, critic and journalist Hector Charlesworth painted a very different picture of Small in 1928:Despite his ability and despite his wealth he seemed to take a positive pleasure in petty acts of meanness and villainy that left incurable wounds. Some of his actions seemed as motiveless in proportion to the possible consequences as those of the villains of Elizabethan tragedy. (275)These two appraisals of Small’s career reveal one aspect of his complex personality. On the business front, though, Small could not easily achieve Grau’s positive financial evaluation without being hard-nosed in his business dealings. Charlesworth was writing some nine years after Small’s disappearance when his actions, as well as the road, had passed into legend. The story behind Small’s disappearance in December of 1919 is well covered in Charlesworth’s book and in Mary Brown’s article "Ambrose Small: A Ghost in Spite of Himself."

Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

15 Correspondence from the Shubert Archives in New York indicates a distinct pattern in how Small conducted business with the offices in New York. Creating and confirming a booking generally took up to four rounds of correspondence:

- A route proposal sent from New York;

- An amended route sent back to New York or the first route approved;

- Contracts showing the agreed route and financial terms sent from New York;

- Finally, the time would be set and completed copies of the contract were held by all parties involved (Small, the New York producer, and the touring manager of the road company).

For the most part, booking proposals came from New York to Toronto, but occasionally Small reserved time for local groups in his theatres by notifying the Syndicate or Shubert booking offices. In all cases though, his actions were strongly influenced and somewhat constrained by American producers. Small was dependent on New York to provide the majority of his productions and could not rely on local groups to fill his theatres.

16 The following correspondence indicates how closely Small worked with the New York producers, in this case, Klaw and Erlanger. Small sent a letter to Charles Osgood, Klaw and Erlanger’s booking manager, on 7 June 1907. In this letter, marked in upper caps as confidential, Small offered Osgood a share of his profits from the Russell in Ottawa for the next season as a "token of gratitude." Small was entitled to one-third of the profits from that theatre and estimated his share at "easily $15,000 to $18,000 if not better." The key to Small’s offer was spelled out in the fourth paragraph of the letter:The Russell is the only house I have on a percentage or booking basis, where I can suggest a divvy of this kind, to say nothing of the fact that I play it principally with the line of attractions in which you yourself are personally interested–the "dollar shows" are also a good winning proposition and the house gets pretty nearly every "local" in Ottawa.Small seems to be implying that if Osgood sent him more and better productions, Osgood’s share of the one-third profit would be higher. Since these extra shows would probably also be booked on the rest of Small’s circuit, Small would ultimately reap even higher profits throughout his empire by sacrificing a part of his Ottawa profits to "grease" Osgood’s hand.

17 The "rounds" of correspondence introduced above taken as a whole reflect the extended negotiations required to book a company on a circuit. Typically, the initial correspondence came to Small’s office as a request for a route between certain dates or as a direct request for certain cities on particular dates. If Klaw and Erlanger directly requested a city, they were usually asking only for time in the major centres of Ontario:Please hold for "The College Widow" Ottawa January 21, 22 1907; Kingston 23; Hamilton 24; London 25, (all next season) and confirm. (Klaw and Erlanger, 4 November 1905)Please hold April 9, Hamilton, for Richard Carle and confirm. (Klaw and Erlanger, 20 March 1908)Usually Small would return confirmation of the dates, but he might make suggestions:Replying to yours of the 4th, I have marked off for "The College Widow", Ottawa, January 21-22, 1907; Kingston, 23; Hamilton, 24; London, 25. Would like to suggest two nights for Hamilton, if at all possible to arrange it that way. (6 November 1905)Normally, the New York office would accommodate Small’s recommendations because of his superior knowledge of the territory, but sometimes the companies had to get to a town in the United States on a certain date and could not spend the extra time in Canada.

18 A letter from Klaw and Erlanger in 1908 for a production of "The Wolf" contained a typical example of a more general route request:Please submit us 5½ weeks tour from October 12 to November 19. They play Montreal October 5 week–Toronto November 19 week–embody Ottawa 3 nights–Hamilton and London 2 nights each with matinees–please give this immediate attention. (15 July 1908)The Montreal and Toronto dates would occur in theatres directly controlled by Klaw and Erlanger (Her Majesty’s in Montreal and the Princess in Toronto). Two days later, John Doughty, Small’s personal secretary, returned a route schedule covering the time required. Doughty’s reply is the second round of correspondence: a proposal or confirmation of route.

19 Many times the proposed route would be accepted and the process would move on to signing contracts. However, in some cases, such as for "The Pink Lady" in May 1913, Small was forced to propose multiple routes. Small’s first proposal, dated 6 May 1913, opened on 12 September in Brockville and closed in Sudbury on 9 October. About three weeks later on 28 May 1913, Small proposed a second route to open in Kingston on 15 September and again to close in Sudbury on 9 October. In the letter, Small detailed three reasons for the amended route. First, he was already holding 27 September for another Klaw and Erlanger show, "The Garden of Allah." Apparently, he had forgotten about this booking in his initial letter, but was reminded about his commitment in the interim.Second, Small wrote that a new theatre was currently under construction in Berlin [Kitchener] and might not be ready until after 1 November. Finally, he rearranged the route to Port Midland after Barrie to avoid using the exact same rail lines twice. Small wrote again on 5 August 1913 with refinements to the route. In this letter, Small lays out two alternate routes and asks Edward Thurnaer, a Klaw and Erlanger manager, to wire him to "fix up ‘The Pink Lady’ contracts for ROUTE NUMBER ONE or ROUTE NUMBER TWO." On 7 August 1913 Small sent a final letter to Thurnaer confirming the company’s route:Am very glad that this route is cleaned up and out of the way, as we certainly did a lot of figuring on it up here to get the show placed to the best possible advantage.This letter, which is really a part of round three of the booking correspondence, acknowledges completion of round four as well. In the final letter, Small wrote that he had filled out the contracts with the route and dates detailed in the 5 August 1913 letter. Even if alterations to the proposed route were unnecessary, a further round of correspondence was often dispatched. The usual round-four correspondence was composed of a simple letter from New York noting that contracts for a particular show were enclosed and that Small should sign and return them.

20 Occasionally, a clause contained in the contracts was unacceptable to a local manager and a round of negotiations began. The most contentious point in these contracts was usually the percentage division of the box office:Respecting the enclosed telegram from Jack Welch, dislike to trouble you in the matter, but if not asking you too much I wish you would kindly explain to him that the terms for "Officer 666" are the same as conceded all other similar attractions in the Canadian cities; that is, 70% in my personal houses at Ottawa, Kingston, Hamilton and London, and 75% in the other cities. The latter, with the exception of Brantford and Peterboro [sic], are all limited to strictly one attraction per week. This idea is not varied or butchered up in any way and we really cannot consistently expect the local manager, under such circumstances, to agree to such a prohibitive percentage as 80/20, which is the sharing basis Mr. Welch has suggested.We want to do everything we possibly can to make it both pleasant and profitable up here for the Cohan & Harris attractions, but at the same time I hope Jack Welch will be fair enough to give the local managers some little lee way for their money, also. (Small, 8 January 1913)The route for the above production of "Officer 666" was already agreed on, but, according to Small, the show’s manager was asking for an inequitable share of the box office. While on occasion Small directly wrote to the manager concerned, this time he called on Klaw and Erlanger to intercede because the "offending" firm was the popular Cohan and Harris partnership. If the owner of the production was less powerful, Small would deal more directly with the problem. Writing to Klaw and Erlanger about the production of "Madame Sherry" on 2 May 1911, Small’s tone is more dismissive:During my absence from the city several very discourteous communications have been sent here by Woods, Frazee & Lederer’s booking representative respecting the [. . .] time for "Madame Sherry" [. . .]. Terms for all of the above to be 80%, excepting Brantford, where 75% is the best the local manager will agree to on Victoria Day, May 24th (formerly called the Queen’s birthday).If they do not care for the time and terms as indicated, they are at liberty to cancel same, but in so doing it will also of course cancel the time held for this attraction in the Canadian cities next season.On the same day, Small wrote an even sterner letter to R. V. Leighton, the representative of the Woods, Frazee and Lederer firm:Don’t bother writing anymore letters about the "Madame Sherry" time. It will be played as originally laid out from Stratford, May 17th, to Belleville, May 26th, or it won’t be played at all, and if you do not care for it that way, simply call it off altogether and cancel the route at present held in the Canadian cities for the same attraction next season. It is a matter of perfect indifference to me whether the attraction comes into this territory at all and I may say to you here that the pleasure of doing business with your office has diminished to such an extent that I prefer to discontinue any further communication with the firm of Woods, Frazee & Lederer while the booking remains in your hands.

21 Small definitely picked his fights carefully; instead of wanting "to do everything we possibly can to make it both pleasant and profitable up here for Cohan and Harris attractions" as in the case of "Officer 666," for "Madame Sherry" "[i]t is a matter of perfect indifference to me whether the attraction comes into this territory at all [. . .] ." The bases for Small’s indifference was doubtlessly his confidence that the Cohan and Harris attraction would generate more income than the Woods, Frazee and Lederer production and that Cohan and Harris were more directly allied to the Syndicate leadership than the other firm. In addition, since most Cohan and Harris attractions were very popular and profitable, it was certainly in Small’s best interests to deal cordially with them.

22 The above exchanges demonstrate the impact of Small’s personality, as he could be quite caustic in his exchanges which could lead to some difficulty for visiting managers. However, his was the only circuit in Ontario that could provide three weeks of bookings. Solman and the Shuberts were trying to establish their own circuit specifically to cut Small out of the business. Solman’s letter to J.J. Shubert on 1 February 1910 makes his attitude very clear:Your shows certainly have been a saviour for Small, and if it were not for them, he would have lost a lot of money on his circuit, outside of Toronto. Do you know, he does not appreciate it, and I, for one, would be glad when we got three weeks in Canada independent of him.At the time, Solman was negotiating with the Bennett company who controlled the Russell Theatre in Ottawa as a first step in establishing their own circuit.6 However, the Shuberts did not establish their own circuit and continued to deal with Small and his personality:The first application I have had for a Shubert attraction this season has just come to hand for "Pinafore", which attraction I would certainly like to play, but hardly at the terms suggested by Mr. Murry. I doubt very much if you will find in any other part of America [sic] territory that would be equally as good for a Gilbert & Sullivan revival as the Canadian cities and I really think you could well afford to accept the terms I have offered Mr. Murry at Hamilton and London, 80%, instead of holding out for such an absolutely prohibitive arrangement as 85/15. (Small, 13 October 1911)

23 Terms were always the most problematic issue with Small. Hector Charlesworth in his More Candid Chronicles recorded that Small tried to manipulate the box office split in his favour by essentially switching the percentages behind the road manager’s back. He often got away with it, but when caught would blame it on his personal secretary, John Doughty.7 Of course it might be argued that neither Small nor any other businessmen could have built such a large empire by conceding the best terms to other companies. Indeed, the Shuberts were notoriously hard-nosed about their business dealings as well.

24 For a tour to be a financial success, producers had to strike a balance between one-night stands and multi-date stops. The performers preferred staying in one location for longer periods, as continuous, daily travel was quite exhausting. For the producer, however, one-night stands could be quite lucrative. The smaller towns were usually less expensive in terms of accommodation and general expenses, and the producer needed to control expenses (which excluded most large-cast productions) due to a smaller potential audience. Larger cities also had more entertainment competition than smaller stops where the theatre might be the only alternative on any particular night. Producers and companies had to work harder to draw audiences in the larger centres. Ultimately, though, simple geography determined the split between one-night and multi-night stands. In the Northeastern United States, there were many multi-night stops. In the Midwest and West, as well as Ontario, the Canadian Prairies, and West Coast, there were many fewer multi-night stops and more frequent movement of companies.

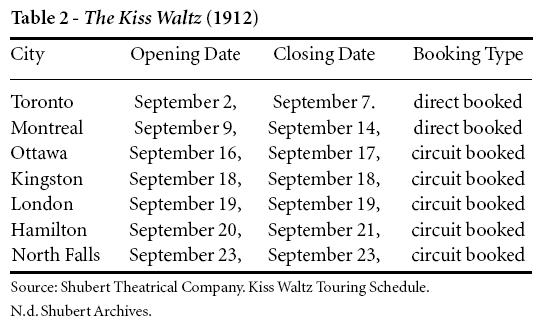

Easy Integration: The Kiss Waltz, 1912

25 The Kiss Waltz was a marquis Shubert production of a Viennese-style operetta that began touring in January 1912. Correspondence from the Shubert Archives shows that during its first year, the original stars from its New York run remained in the show, but for the touring segment in Ontario and Quebec in September 1912, the star was Valeska Suratt. The Canadian portion of the route played in 1912 is detailed in Table 2. The company played Toronto for a full week including matinees on Wednesday and Saturday. On their off day (Sunday), the company travelled to Montreal to be ready for a Monday opening. After a full week in Montreal, the company headed back to Ontario. In Toronto, the production played at the Royal Alexandra and in Montreal it played the Princess Theatre, both directly booked by the Shuberts through Entertainments Ltd. The rest of the dates in Ontario were circuit booked. In order to make this high-cost, large-cast operetta financially viable, the company played only major stops in Ontario, with the exception of North Falls, after which date the company headed back into the United States. The stops on this route were easily reached either by overnight train or on the company’s day off. If this was a smaller and less expensive company, they would have played more one-night stands in Ontario before returning to the United States.

Table 2 - The Kiss Waltz (1912)

Display large image of Table 2

26 During the first two decades of the twentieth century, the booking of theatre companies on the road had become systematic. Two types of arrangements had evolved to allow companies to tour profitably: direct control and circuit booking. The Shuberts engaged in direct control in Canada via a subsidiary corporation called Entertainments Ltd. While this company was a partnership with a Canadian businessman, Lawrence Solman, the Shuberts had full control over the companies sent to the theatre and also exerted a great deal of influence over the actual theatre operations. In the correspondence between New York and Toronto, booking matters are mostly absent as the Shuberts arranged the booking directly from New York. The arrangement was quite profitable for both the Shuberts and for Solman. The Shuberts, however, garnered profits not only as theatre owners, but also as the owners of many of the other companies that played the Royal Alexandra and Princess Theatre. While there was little difficulty in the booking arrangements for the directly controlled theatres, the circuit-booked theatres required more negotiation. Many rounds of correspondence were required to arrange for tours across the circuit belonging to Ambrose Small. This extra effort was worthwhile because the circuits provided dates between the major centres that would break up the travel required and provide revenue for the companies on the road to fund their extensive travelling. Essentially, the circuit stops only had to generate enough revenue to cover expenses because the producers would reap their major profits in the directly controlled theatres. Since the producers had no financial investment in the circuits, when business began to decline, they rerouted their companies to more profitable territory and integrated the directly controlled theatres into their schedules in an alternate fashion. While the road was flourishing, both of these systems worked together to provide profits for theatre owners and producers. However, this system broke down after the First World War and circuit booking disappeared, though companies continued to visit Toronto and to a lesser extent Montreal.

Works Sited

Bernheim, Alfred L. The Business of the Theatre: An Economic History of the American Theatre, 1750-1932. New York: Benjamin Blom, 1964. Print.

Bird, Charles A. Letter to George McLeish. 21 July 1909. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to George McLeish. 9 August 1909. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to George McLeish. 11 August 1909. Shubert Archives. TS.

Brown, Mary. "Ambrose Small: A Ghost in Spite of Himself." Theatrical Touring and Founding In North America. Ed. L.W. Conolly. Westport: Greenwood, 1982. 77-88. Print.

Canadian Theatre Co. Ltd. and Entertainments Ltd. Contract. 24 April 1909. Shubert Archives. TS.

Charlesworth, Hector. More Candid Chronicles. Toronto: MacMillan of Canada, 1928. Print.

"Toronto History FAQs." City of Toronto Archives. Web. 5 July 2008. <http://www.toronto.ca/archives/toronto_history_faqs.htm>.

Entertainments Ltd., Canadian United Theatres Ltd. and the Canadian Theatre Co. Ltd. Contract. 30 October 1916. Shubert Archives. TS.

Grau, Robert. The Business Man in the Amusement World. New York: Broadway, 1910. Print.

Klaw and Erlanger. Letter to Ambrose Small. 4 November 1905. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Ambrose Small. 20 March 1908. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Ambrose Small. 15 July 1908. Shubert Archives. TS.

Leavitt, M.B. Fifty Years in Theatrical Management. New York: Broadway, 1912. Print.

O’Neill, Mora Dianne Guthrie. "A Partial History of the Royal Alexandra Theatre, Toronto, Canada 1907-1939." Diss. Louisiana State University, 1976. Print.

Poggi, Jack. Theatre in America: The Impact of Economic Forces, 1870-1967. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1968. Print.

Shubert, J. J. Letter to Lawrence Solman. 2 February 1910. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Lawrence Solman. 2 March 1915. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Lawrence Solman. 28 June 1915. Shubert Archives. TS.

Shubert Theatrical Co. and Entertainments Ltd. Contract. June 1909.

Shubert Archives. TS.

Small, Ambrose. Letter to Klaw and Erlanger, 6 November 1905. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Charles Osgood, 7 June 1907. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Klaw and Erlanger. 2 May 1911. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to R. V. Leighton. 2 May 1911. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Lee Shubert. 13 October 1911. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Klaw and Erlanger. 8 January 1913. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Klaw and Erlanger. 6 May 1913. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Klaw and Erlanger. 15 May 1913. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Edward Thurnaer. 28 May 1913. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Edward Thurnaer. 5 August 1913. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Edward Thurnaer. 7 August 1913. Shubert Archives. TS.

Solman, Lawrence. Letter to J. J. Shubert. 29 December 1909. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to J. J. Shubert. 1 February 1910. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to J. J. Shubert. 31 December 1913. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to J. J. Shubert. 1 January 1916. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Lee Shubert. 8 April 1916. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Lee Shubert. 8 April 1916. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Letter to Lee Shubert. 4 October 1918. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Telegram to J. J. Shubert. 9 October 1918. Shubert Archives. TS.

Solman, Lawrence, Lee, and J. J. Shubert, and Entertainments Ltd. Contract. 13 January 1909. Shubert Archives. TS.

— . Contract. June 1909. Shubert Archives. TS.

Solman, Lawrence, Shubert Theatrical, and Lee, and J. J. Shubert. Contract. 22 December 1908. Shubert Archives. TS.

Solman, Lawrence, Shubert Theatrical Co., Lee, and J. J. Shubert, and Entertainments Ltd. Contract. 30 October 1916. Shubert Archives. TS.

Notes