Forum

"A Condor in the Andes of the Seats":

Guthrie at Stratford, 1954

Peter CarnahanTheatre and Literature Programs of the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts

Abstract

Peter Carnahan presents a personal memoir of Tyrone Guthrie’s second season as Director of the Stratford Shakespearean Festival of Canada, with observations on his directing techniques for The Taming of the Shrew and Oedipus Rex and other Guthrie productions of the period, and considerations of his contributions to the field of Shakespearean staging, particularly his use of "modern dress" costuming and his pioneering development, along with Tanya Moiseiwitsch, of the open stage for Shakespearean production. The article concludes with personal reminiscences of Tony and Judy Guthrie as they relaxed and enjoyed the life of a small Canadian town after the season opened.Résumé

Peter Carnahan présente un compte rendu personnel de Tyrone Guthrie et de sa deuxième saison à la direction artistique du Stratford Shakespearean Festival of Canada. On y trouve des observations sur les techniques de mise en scène employées pour The Taming of the Shrew, Oedipus Rex et d’autres pièces sur lesquelles Guthrie a travaillé à l’époque, ainsi que des réflexions sur la contribution de ce dernier à la mise en scène de l’œuvre shakespearienne, notamment son emploi de costumes « modernes », et son usage pion-nier, avec Tanya Moiseiwitsch, d’une scène ouverte. L’article conclut avec quelques détails que retiennent Tony et Judy Guthrie d’une vie paisible passée dans une petite ville canadienne une fois la saison de théâtre entamée.1 Theatrical directing, Tyrone Guthrie once remarked, is "writing on water" (A Life 147); when the production is over, it vanishes. True, but not always true. In the summer of 2005 I found myself standing outside a pub near St. Paul’s Cathedral in London talking with the Canadian actor Colin Fox about Tyrone Guthrie’s extraordinary stage skills, thirty-five years after the great director’s death. We both talked excitedly, as if we had seen him work the day before.

2 Fox had done a one-man show, Guthrie On Guthrie,1 at the Stratford Shakespearean Festival of Canada in 1989, and later on CBC radio.Our conversation ignited memories for me of the long-ago summer of 1954 that I had spent watching Guthrie direct.

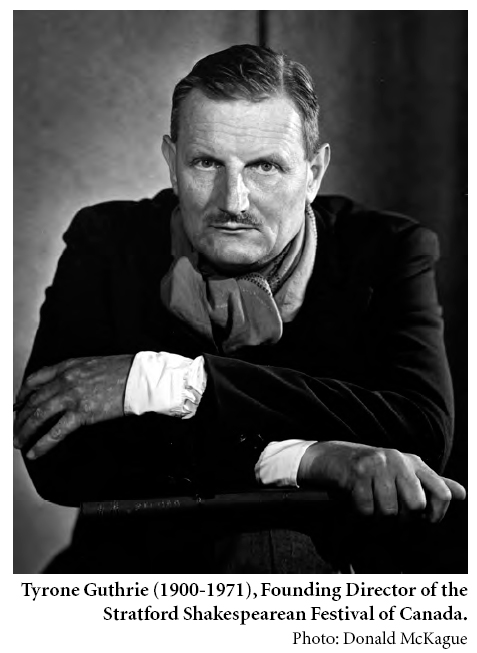

Tyrone Guthrie (1900-1971), Founding Director of the Stratford Shakespearean Festival of Canada.

Display large image of Figure 1

3 It was the second season of the Stratford Festival.2 A week before the opening, on a warm Sunday evening in June, I went down to the large tent theatre by the River Avon where a rehearsal of The Taming of the Shrew was in progress. My escort,my aunt Helen Griffith, a member of the original board of directors, pulled back the tent flap and whispered briefly with the man who was guarding it and we were let inside, amidst the smell of treated canvas and the muffled sounds of actors’ voices coming from beyond a second canvas wall. Another flap opened and we were looking down into the theatre.

4 I won’t forget that first sight from the rim of the auditorium: the precipitous, bowl-shaped arena of seats below us, a startling anomaly in a world of proscenium stages, a few people sitting or standing here or there on its slopes, tent poles spearing up like masts of some enormous ship, the prow of the stage building projecting out into the audience way down there at the center of the 210 degree arc of seats.Helen and I quietly slipped into two seats near the top.A small scene from Act 4 was under way with three or four characters, Vincentio, Baptista, Tranio. . . that ended in a tussle and the line "Call forth an officer" (2469).3

5 Immediately, from all over the empty auditorium under its huge sail of a roof, police whistles shrilled and continued to shrill; up, back, and around us people yelled; crowds came streaming down the aisles, out the doors of the stage building, vomited up out of the ramps below the seating. In a matter of seconds the nearly empty stage was filled with sixty citizens of Padua, all shouting, haranguing, laughing, dancing, witnessing, and commenting on what had been a small argument at the center of the stage. It was a bus accident, a scene from Brueghel. It left me breathless. It was my first experience of the tumultuous stage magic of Tyrone Guthrie.

6 And there he was, an out-sized figure standing in the fourth row, bare-footed, dressed in blue pants and blue jacket top that couldn’t quite meet at the waist to cover his six-foot and more than six-inch frame, clapping his hands and stopping the action. He said a few, a very few polite words to the throng of actors, who listened intently, then clapped his hands again and uttered a loud, braying "Baack!" and everyone reversed up the aisles and down into the vomitoria. Guthrie sat and a dark, equally aquiline woman, a pre-Raphaelite priestess, handed him tea from a thermos in the plastic top. "Judith Guthrie," my aunt whispered to me, "his wife."

7 When the Festival began the previous summer, bursting upon the Canadian scene with a brilliance that immediately established it as one of the world’s important theatres, I had been in the final year of my service in the US Army, and directing plays on post in my spare time. I was in Stratford the following winter and found the town still humming with excitement from the glory of that first season. So when my army term was up the next June, I got in my car and drove from Fort Knox, Kentucky, to Stratford in a day and a half, ending up that night high in the Festival seats watching the magician Guthrie do things I never dreamed the stage could be made to do.

8 "Stage magic" was—literally—one of Guthrie’s favorite techniques: the magician’s stock-in-trade of diverting the attention with one showy hand, while the other sly one accomplished the trick.

9 In his production of Six Characters in Search of an Author4 in New York City the following winter, he used this technique for the first appearance of the mysterious family of the title. Another director might have brought them up on an elevator from below the stage or revealed them with light from behind a scrim or through smoke. Guthrie never used mechanics when people would do—a trait that was perfect for Stratford’s thrust stage. You want to elevate an actor? You don’t build a cumbersome stage platform to stumble over the rest of the play. You get three people around him and they lift him up. You want musical underscoring for a scene? No amplifiers, buzzes, pops, cues to be missed. Three actors go to the side of the stage and sing softly. No mechanics. Everything human. Everything from the body, the actor’s instrument.

10 For the appearance of his six characters, Guthrie engineered an extremely loud commotion just before the entrance of the family, in which the ten actors then on stage all shouted and rushed frantically over to the down right corner of the stage. When you looked back, six mysterious people were standing quietly at the center. The other actors gasped. You gasped. They seemed to have appeared from nowhere. They had, very likely, simply walked on to that position, but such is the magician’s power to divert attention that you could not have seen them enter.

11 The Six Characters production was full of virtuoso touches like that. The director and critic Harold Clurman called it "a course in stage direction" (130).

12 Perhaps Guthrie’s most ambitious piece of stage magic was described by Jessica Tandy in Alfred Rossi’s book Astonish Us In The Morning.5 Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night turns on the remarkable resemblance of identical twins Viola and her brother Sebastian, who, sinceViola is masquerading as a boy, are comically and romantically mistaken for each other throughout the action. Guthrie cast Ms. Tandy in both roles. This worked easily, as Viola and Sebastian scenes alternate and they never meet, until the final scene, when they are, after long separation, reunited, to their mutual joy. How did Guthrie manage that? With a double, yes, but as Ms. Tandy described it:I spoke all the lines, either one or the other. Earlier in the play [. . .] Olivia had given me a flower, which I had tucked into my hat as Sebastian. So after that, every time I came on as Sebastian, the flower was in the hat. Now when they were both on at the same time—there were a lot of people on stage—I would say one line as Viola, and we would rush together and turn, and the flower would be in the hat, and I’d say the next line [as Sebastian], so it was a sort of ballet. It worked, and was very exciting. (Rossi 232)But to recount such bits of magical invention does not do justice to Guthrie’s scope as a director. His talent was much more than just a bag of tricks. As a colleague of mine remarked, it was Guthrie’s concept of a play that was often highly original.

13 In the production of Shrew that I walked in on that June evening in 1954, the next surprise was Petruchio. When he appeared on stage, he was not the usual blustering, strutting, macho male, but a gangly, mumbling, bumbling Bill Needles, who with his hesitant manner and horn-rimmed glasses (the production was dressed circa 1910 western Canada) looked and behaved for all the world like the silent movie comic Harold Lloyd. This was Petruchio? The tamer of the most shrewish woman in Padua?

14 Guthrie later explained where he got the idea. He had been directing a production of Shrew at a community theatre in Finland—in the days before Stratford, Guthrie would go anywhere in the world and direct in any theatre, if the project were interesting. He was stuck with an amateur Petruchio who was just not up to the usual bombast, and as he watched the hapless actor struggle through his part, he suddenly realized, this was the way the role made sense.

15 In real life, he said, how often do you see a blustering, boastful type of man pairing with a loud, aggressive woman? Isn’t it much more common for such a woman to marry a meek, "hen-pecked" husband—who often turns out to be, in private, a very tiger about the house? He recognized this psychological truth in his struggling actor’s performance in Finland. In the Stratford production of Shrew, Katherine, played by Barbara Chilcott, came roaring on the stage to confront her arranged suitor and send him packing. She stopped, utterly confounded by the sight of this nervous, timid soul. She looked out at us and uttered a soft, touched "Oh!" and we knew she had taken him to her heart. Everything worked after that. As Petruchio struggled to master Kate, his inner strength emerged, and as she learned to accept him, her inner warmth and softness.

16 It was not just pop psychology, however brilliant. Guthrie credited Shakespeare, who has Petruchio say "‘Tis a world to see / How tame when men and women are alone, / A meacock wretch can make the curstest shrew" (1191-93).

17 One of Guthrie’s concepts that most intrigued Stratford audiences in those beginning years was "modern dress" Shakespeare. Through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, despite a few experiments by producers such as Harley Granville-Barker, Shakespeare was usually staged either in "realistic" dress, i.e. Julius Caesar in togas, Macbeth in kilts, or in Elizabethan dress. Guthrie had done a modern dress Hamlet, the court in evening dress, with Alec Guiness at the Old Vic in the late 1930s, but when he came to Canada, the newness of the scene, of the thrust stage that he and Tanya Moiseiwitsch designed, the desire to do "Canadian Shakespeare" rather than a tepid imitation of the English style, all led to new thinking about the physical productions. In the first season Richard III was costumed in historical period, but for the other production, All’s Well That Ends Well, the Court of France was costumed in gorgeous high-Edwardian style.

18 The production of Shrew that I encountered the second season was done in a kind of crazy, off-beat "wild west" costuming that represented Guthrie and Moiseiwitsch reaching rather hard for a "Canadian" style. Neither was happy with the result; it went too far, or did not go far enough. After the production was on, Guthrie was discussing the failure with Ray Diffen, their highly-reputed costume cutter imported from the London theatre. "Oh," said Ray, "if you had just said that one word, ‘ballet,’ I could have done it for you" (Guthrie, Conversation).

19 Guthrie productions were not, in fact, "modern dress," but dress of a period other than Shakespeare’s or the supposed period of the story. What distinguished them was that the period was always chosen for a reason: All’s Well because the gilded age was close enough to be remembered and suited the splendor of the French court, Shrew because the production was going to be more than a little wild and uninhibited. For a later Stratford production of Twelfth Night6 he and Tanya decided on costumes based on Van Dyck’s seventeenth-century portraits, because the shoulder-length hair styles of the men made the resemblance of Viola and Sebastian easy and because the warm browns of Van Dyck’s palette seemed to them to suit the mood of the play.

20 Perhaps the greatest gift of Guthrie and Moiseiwitsch to the contemporary theatre was the open Stratford stage itself. In the mid-twentieth century, the theatre seemed inexorably locked into the picture-frame stage. The curtain goes up on a pretty, painted scene, comes down and goes up on another pretty, painted scene: pictures in frames, viewed from a gallery seat.

21 Guthrie had long felt that this method of staging was particularly awkward for Shakespeare, with his many brief scenes and changes of locale (A Life 202-14). The first production of Tanya’s that he saw, The Merchant of Venice at the Playhouse, Oxford, in 1944, he pronounced "too uppy downy," the curtain constantly descending for another brief scene to be set (Barlow 9). Tanya agreed, and over the next nine years the two of them worked on the problem individually and together.

22 Guthrie had been profoundly impressed by a near-mischance in 1937. They had taken his Old Vic production of Hamlet with Laurence Olivier to Elsinore in Denmark, to be performed out of doors. On the appointed night the rain came down "in bellropes" (A Life 190).In an hour’s time the production was moved to a hotel ballroom and performed in the middle of a circle of chairs. Guthrie never forgot the effect, the swift flow of the action, the vital closeness to the audience.

23 In 1948, in searching for a hall to stage The Satire of the Three Estates at the Edinburgh Festival, he elected the large, square room of the Assembly Hall (A Life 307-09), and there the three-sided thrust stage that was to become, in Moiseiwitsch’s beautiful design, the Stratford stage, was first tried out, to great acclaim.

24 After the triumph of Stratford, Moiseiwitsch went on to design similar stages for the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis, MN, and the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield, England (Behl 85). The design was copied by many theatre architects, not always successfully. The first large theatres built in the US in imitation of Stratford were unfortunate failures of nerve. Designers couldn’t quite bring themselves to give up the fly loft of the proscenium theatre, so they built, at Stratford, CT and Lincoln Center in New York, awkward compromises. The first was a conventional proscenium theatre separated from the audience by a large apron, the second a wrap-around audience where the people on the sides couldn’t see into the proscenium opening.

25 Eventually, the lessons of Stratford took hold. Now open stages are common in Canada and the US, using Moiseiwitsch’s steep stadium seating and the single-chamber construction that puts the actors in the same room as the audience. These new theatres preserve what Guthrie and Moiseiwitsch gave us: a fresh, revived relationship between actor and audience.

26 Somewhere during that week before the Festival’s 1954 opening, Helen introduced me to Guthrie at a social event. The thing you noticed about him was his size. He was a giant of a man, and his authority first, but only first, stemmed from that. "Guthrie a condor in the Andes of the seats," I wrote in a poem describing rehearsal, "From a great nest of politeness, the threat of soaring" (Carnahan). I remember once, at a crowded reception, looking across the room and seeing Guthrie’s head, with its triangular Roman nose, a full head above the sea of other heads.

27 But the moment you met him another force took over: the enormous attention that he focused on you.Questions pelted down the searchlight of his stare—Who are you? What brings you here? What do you do in life? What do you want to do in life? Why do you want to do that? He shut the entire world out for a few minutes and concentrated on you alone, soaking up your life story and filing it away for future use. All grist. It left you amazed and flattered, even as you watched him move on and do it to someone else.

28 Later that summer, we were all up at the Lake Huron shore where my aunt Helen’s friends had cottages. After a mellow picnic on the beach, we were expected at one of the cottages where Helen had promised to introduce the great director. It was dusk after a long day and we had an hour’s drive back to Stratford, but Guthrie greeted the hosts with gusto and insisted on a tour of every room in the cottage. "So this is how Canadians live in summer cottages! Ah, and this is the laundry! I see! Oh, and what is through here? A bedroom! And are those stones from the beach? And how do you heat the water?" In a matter of twelve minutes we were back in the car, leaving our hosts dazed but pleased, with Guthrie sitting in the back seat having sucked up every detail, locking away the information under Summer Cottage Living/Ontario.

29 As we drove down the lane, he looked out at the dusk sky. "Those clouds—peculiarly Canadian clouds. We don’t have those clouds in England," then at the ripening fields of grain, "What is that? I think it’s barley.Yes, barley."

30 To which his wife Judy said,"Oh, don’t be silly, Tony."And to us, "He doesn’t have the least idea what that is." He put his great head back in the back seat and went to sleep.

31 While these qualities—curiosity about everything, concentration, listening—served him well socially, they were also the qualities, applied professionally, that made him a great director.

32 I had already worked with a number of "strong" directors. One of the pitfalls for such an artist is that he often cannot see what the actor is doing, only what he wants the actor to be doing to fit into his brilliant scheme. Most of the battles between actor and director stem from this. Guthrie rarely battled with actors. He was unique in the extent to which he could see and hear what the actor was actually doing, rather than what he wanted him to do, and take that and make something of it. This could lead a scene off in a strange direction, not part of the master plan, but that didn’t bother Guthrie if it worked. His productions would often be jumbles of disparate things, messy assemblages with plenty of rough edges. What I learned from him was the rough edges don’t matter. It is the strong parts that matter, and are remembered. If he could make a strong moment, he made it, and the Devil take consistency.7

33 This democratic willingness to take what the actor proffered and work with it, seemed unexpected humility in such a great intellect. (Guthrie was always amazing us with the scope of his thinking. While we were trudging up the ladder of an idea, step one, step two, step three, he would vault to the top in a single bound.) But there was method in his humility. When a scene was rehearsing, he would often prowl the auditorium and plunk himself down next to a surprised observer. After a moment he would lean over and say, "What do you think of that choreography there, when they go out the door? Is it the right rhythm? Does it work?" Overcome with your sudden importance, you would nod a "Yes," and watch him take off and prowl again.Your heady moment would be somewhat tempered when you saw him sit down next to a minor actor,one who was considered one of the slower wits in the company, and ask the same whispered questions. Then he would stop the action and say, "Keith suggests that it would work better if you came down to the steps before the speech. Let’s try it. Baack!" Guthrie realized that even the dimmest mind can have a fresh idea. Keith is enormously flattered. Guthrie gets a better scene.

34 My great learning experience that summer was watching Oedipus Rex, which, since it opened several weeks after Shrew and Measure, was just in the middle stages of rehearsal. It was the chorus that fascinated me: fifteen male members of the company, among them Donald Harron, Bruno Gerussi, and William Shatner, led by William Hutt. Guthrie divided them into tenors, baritones, and basses, and divided up the lines of each chorus, giving a solo line here, a line to three tenors, a line to two basses, then three lines for all fifteen voices, topped by a solo line by William Hutt soaring out above the symphony of sound. It was thrilling. Guthrie later wrote that he chose the William Butler Yeats version of the play because the choruses were poems in their own right.8 And what use he made of them, crafting each one as a triple quintet, even at one point having the poem rise spontaneously into song.

35 The fascination of watching Guthrie develop these choruses was only surpassed by seeing their effectiveness in performance. A chorus of actors commenting in unison on the action of a play seems to us the most rickety and antique of theatre conventions. Okay for the Greeks back then, but in our realistic theatre, pompous and slightly absurd. The chorus in Oedipus Rex was the most exciting thing in the show. They were physically in the middle of the action, passionately involved, and it was their passion that electrically transferred to us in the audience the passion of the elevated, masked, iconic figures who were Oedipus, Jocasta, and Creon.

36 It is sometimes difficult in a classical play to figure out what is happening, but with a chorus of fifteen on stage reacting to every nuance of Oedipus’s growing doubt, Jocasta’s growing fear, Creon’s indignation, our reactions were keyed immediately to the chorus. Watching them, we knew—and felt—exactly what was going on.

37 (In his Shakespeare productions as well, Guthrie used a "chorus," twenty or thirty extras, anonymous characters who would become townspeople, soldiers and camp followers, courtiers, courtroom audiences. Their reactions signaled us in the audience in the same manner. It was always very clear what was happening at any moment in a Guthrie scene.)

38 A second lesson I learned from Guthrie’s Oedipus: passion reflected is passion redoubled. It used to be a cliché that in Greek drama all the real action happened off stage. Either the Greeks were squeamish or clumsy at dramaturgy. In Guthrie’s Oedipus, when the second messenger, played by Douglas Rain, came on to describe Jocasta’s suicide and Oedipus’s blinding of himself, he was, from the start, shaken. As the scene built and he remembered what he had seen, his terror mounted to the climactic lines: "He dragged the golden brooches from her dress and lifting them struck them upon his eyeballs, crying out ‘You have looked long enough upon those you ought never to have looked upon, failed long enough to know those that you should have known; henceforth you shall be daaark!’" (Yeats 325). It was the most powerful moment I’ve ever experienced in the theatre, far more terrifying than if we had seen Oedipus actually perform the act, with all the necessary fakery and stage blood. The mind is where the theatre takes place.

39 After Oedipus opened, things slowed down and I had an opportunity to know the Guthries socially. Once I was invited over to their house "for mint juleps." Mint juleps? What did the Guthries have to do with this genteel custom of the American south? I found Tony and Judy reclining in deck chairs in the unmown grass of their backyard, along with an American director whom I knew slightly.9 The mint juleps may have been in his honour, although he was from Massachusetts. Tony made the drinks. A Guthrie mint julep was made by pouring a large quantity of bourbon into a water tumbler. One then reached over the side of the deck chair, plucked leaves of mint growing wild in the grass and pushed them down into the bourbon. Delicious, after the first.

40 I think it was on the same occasion that they talked about a tea shop in a village they knew in England where you could go in and order a "special cup of tea," which would be Scotch but, of course, the same color as tea. I thought about the tea thermos at rehearsals but dismissed any concern. On a frame as large as Tony Guthrie’s, it would take at least half a bottle to have any effect.

41 He knew that I wanted to be a director, and occasionally offered encouragement. "I think you’re much more confident than you appear to be on the surface," he said to this twenty-three-year-old, "For all your shyness, I think you know exactly what you want to do" (Guthrie, Conversation). Tony did not have much patience with shyness. One should simply get on with it.

42 Another time he said, "You can do anything on the stage that I can do. The only advantage I have is that I can make Bill Hutt get up in rehearsal and make a damn fool of himself, and then shut the others up when they laugh at him" (Guthrie, Conversation). He was referring to a moment in rehearsal two weeks earlier when he had asked Hutt to take a line up, "Higher! Higher!", until his voice broke. Despite the titters from some cast members, Hutt knew what he was being asked to do: test the limits. "Shut the others up when they laugh at him" was Guthrie’s way of talking about his authority as a director. We both knew that one advantage was a good part of the game.

43 Later that summer, I rode along with board member Archdeacon F.G. Lightbourn and his wife Mary as they drove the Guthries to Pearson Airport in Toronto for their return flight to England. I remember Tony quizzing me again about my career ambitions, and I must have expressed some frustration, for he said, "What are you in such a hurry for? Nothing is so sad as the man who has all his success at twenty-five, and spends the rest of his life trying to live up to it" (Guthrie, Conversation).

44 I thought at the time that he was alluding to Orson Welles, the boy-genius of the 1930s, who was then in eclipse and financial exile. Later, I wondered if he were referring to himself, since his own career was in modest eclipse when he came to Stratford and triumph.

45 Waiting for flight time, we had a pleasant lunch in the airport restaurant. As we rose to pay the bill, Archdeacon Lightbourn snapped it up and said, "This is mine."

46 "No, no, dear boy," Tony said, "Mine."

47 The bill was snatched back and forth, amid growing chuckles, until the courtesies developed into a wrestling match, the short, rotund Archdeacon, in his Anglican collar, tackling the enormous theatrical director around the waist, two schoolboys going at it there in the middle of the restaurant. We eventually parted them, but my last memory of Guthrie that summer is of him laughingly fending off the attack of a middle-aged cleric. He certainly enjoyed himself in Canada.

Works Cited

Barlow, Alan. "Tanya Moiseiwitsch and the Work of the Stage Designer." Edelstein 7-10.

Behl, Dennis. "A Career in the Theatre." Edelstein 30-123.

Carnahan, Peter. "Stratford 1954." Poem. 15 October 2008 <www.peter-carnahan.com>.

Clurman, Harold. Lies Like Truth. New York: Macmillan, 1958.

Davies, Robertson, Tyrone Guthrie, Boyd Neel, and Tanya Moiseiwitsch. Thrice the Brinded Cat Hath Mew’d. Toronto: Clark, Irwin, 1955.

Edelstein, T.J. organizer. The Stage Is All the World, The Theatrical Designs of Tanya Moiseiwitsch. Chicago, Ill.: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago in association with the U of Washington P, 1994.

Guthrie, Tyrone. A Life in the Theatre. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1959.

— . Conversation with the author. November, July 1954.

— , Robertson Davies, and Grant Macdonald. Twice Have The Trumpets Sounded. Toronto: Clark, Irwin, 1954.

Rossi, Alfred. Astonish Us in the Morning. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1980.

Shakespeare, William. The Norton Facsimile The First Folio of Shakespeare. Prepared by Charles Hinman. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1968.

Yeats,William Butler. "Sophocles’ King Oedipus, A Version for the Modern Stage." The Collected Plays of W. B.Yeats. New York: Macmillan, 1953.

Notes