Articles

From Performing Wholeness to Providing Choices:

Situated Knowledges in Afrika Solo and Harlem Duet

Marlene MoserBrock University

Abstract

This paper considers two plays by Djanet Sears, Afrika Solo and Harlem Duet, under the rubric of feminist standpoint positioning. The situated knowledges of standpoint positioning avoid the "god trick," as Donna Haraway puts it, of the objectivist approach, but lead to other anxieties and limitations around subjectivity and agency. Both plays consider the performative and contextual nature of identity, but their spectatorial relationships offer different paths to agency and knowledge and challenge us to entertain certain epistemological shifts.Résumé

Cet article porte sur deux pièces écrites par Djanet Sears, Afrika Solo et Harlem Duet, en privilégiant la théorie de positionnement féministe. Le savoir acquis en situation qui caractérise la théorie de positionnement permet d’échapper au « stratagème divin » (god trick) comme l’appelle Donna Haraway, d’une approche objectiviste, mais entraîne d’autres questions quant à la subjectivité et au rôle d’agent. Les deux pièces examinent la nature performative et contextuelle de l’identité, mais la relation établie avec le spectateur dans chacun des cas débouche sur différentes présentations du rôle de l’agent et du savoir et nous propose d’examiner certains changements d’ordre épistémologique.1 Afrika Solo and Harlem Duet invite comparison, in their movement from comedy to tragedy, from personal history to literary re-visioning, from playwright-driven solo performance to counter canonical text–cum-domestic drama. In some ways the plays are profoundly different: Afrika Solo is an early foray into playwriting, drawing on a performer’s charisma and drive; and Harlem Duet is a sophisticated, highly crafted, mature drama. Despite the different audience-stage relationships initiated by the conventions of genre and stylistic choices, there is a remarkably similar foregrounding of performatively constructed models of identities in these two plays. Identity is always transitional and multiple; roles and interpretative mechanisms are blurred. In their valuing of local bodies of knowledge and contingent framings of truth, Afrika Solo and Harlem Duet can be read through the lens of feminist standpoint positioning, inflected by race, demonstrating both the possibilities and anxieties of agency.

2 Standpoint theorists,such as Sandra Harding,suggest that the social groups we are associated with shape our ideas and beliefs and that what we know is necessarily local, contingent, and "socially situated"(11). Much early feminist standpoint theory, for example, valued stories of the lives of women. Standpoint theory has a"folk history"as Harding describes it,"in its apparently spontaneous appeal to groups around the world seeking to understand themselves and the world around them in ways blocked by the conceptual frameworks dominant in their culture" (3). As such, it is intimately connected to knowledge gained through the experience of oppression. Harding notes how "standpoint theory is a kind of organic epistemology,methodology,philosophy of science, and social theory that can arise whenever oppressed peoples gain public voice" (3). This approach stands in contrast to the objectivist approach of scientific analysis, the "god trick" as Donna Haraway puts it, in which everything is spoken about authoritatively without an acknowledgement of any particular social location or point of view (87). Instead, Haraway continues,"Feminist objectivity is about limited location and situated knowledge, not about transcendence and splitting of subject and object. In this way we might become answerable for what we learn how to see" (87). This "becoming answerable" helps us to understand ways to deal with the charges of relativism that are made against feminist standpoint positioning. Harding, for example, sees this characteristic as a strength and not a weakness, reminding us always of how difficult it is to separate ourselves from the project of Enlightenment and singular, truth-based vision. Harding suggests that we cannot separate one set of knowledge claims (science) as somehow not being "socially located" and "permeated by local values" when others are (11). "Instead," she suggests, "we need to work out an epistemology that can account for both this reality that our best knowledge is socially constructed, and also that it is empirically accurate" (12). Managing these apparent contradictions is one of the challenges of feminist standpoint positioning. But this kind of thinking leads to some provocative ways of reading and understanding knowledge. Sociologist Patricia Collins, for example, develops the idea of the "outsider within" to describe a sense of engaging within community to a degree, while being excluded from aspects that are more privileged. This theorizing has been useful for applications of standpoint theory in considerations of race. Collins uses the term to describe the example of AfricanAmerican women employed as domestic help within white families where they became "honorary members" of their white families, but never belonged (Fighting 7). Collins sees how this "outsider within" status can be used to obtain distinctive visions for subjugated groups, who are at the intersection of systems of oppression. Situated neither within an elite knowledge group, nor engaged solely in an oppositional stance, "theorizing from outsider-within locations can produce distinctive oppositional knowledges that embrace multiplicity yet remain cognizant of power" (Fighting 8).

3 Reading Afrika Solo and Harlem Duet with feminist standpoint positioning in mind can help to situate the two texts, as well as highlight some of the controversies and limitations of this theorizing, especially as the plays can be seen to demonstrate different facets (both strengths and weaknesses) of this approach. Afrika Solo shows the empowering effects of standpoint positioning, but its knowledge claims, though acknowledged as performative, are largely singular. When the multiplicity and contradictory knowledges of standpoint positioning come to the fore, as they do in Harlem Duet, agency is much more difficult. In the construction of different spectatorial relationships, the plays offer different points of access to knowledge.

4 Afrika Solo can be considered through the rubric of feminist standpoint positioning on one level simply because the play seems to proclaim the coming of age of Djanet/Janet the playwright. The play chronicles her coming to consciousness, using her own journey to Africa as a point of departure. It is useful to examine the ways in which this voice, or "situated knowledge," is portrayed in this play,as it helps to convey the complex nature of feminist standpoint positioning. In the "Afterword" to the play, Sears uses Audre Lorde’s term "autobiomythography" to describe the expression of her own experiences in a fictional landscape (95): though the markers of her real presence as actor and playwright are strong, there are just as many qualifiers in the play that acknowledge its own performativity. In addition to the blurring of fiction and fact in the writing, the play is essentially a performance, documented by a script. Sears is simultaneously character, actor, and playwright, as indicated by framing mechanisms in the publication: the photographs of Sears herself performing, the use of her name as a character, her testimonial in the "Afterword." Dramatic techniques in the script itself also sustain this quality: Afrika Solo is told to us as well as enacted for us, as Janet/Djanet alternates between narration and action. In addition, the setting is in a transitional space, an airport, beginning at the end of her trip, as Djanet waits for a stand-by flight to take her home to Canada. The play has a circular structure taking the audience on a retrospective journey, only to end up where the journey began. In many ways, Djanet remembers this piece, both in the way she frames and foregrounds her experiences through memory and in the way she puts pieces together, sifting through her perspectives on her experiences, until she shapes a suitable identity. Framed and related in these ways, Sears foregrounds how she takes herself as the object of inquiry, implicitly blurring any subject/object divide. Afrika Solo negotiates between essentialist and constructivist views of identity. By the end of the play, Sears in catching her own ‘I’ [sic] (93) is articulating an affirmation of this feminist standpoint positioning, in which she recognizes the legitimacy of a situated knowledge and in which object and subject are not split, but rather fused. She escapes the "god trick," as Haraway calls it, in her infusion of the national with the particular, especially in her singing of "O Canada." Although she takes on a kind of voice of authority, in her singing of the national anthem or in her declaration of identity, she also always undermines this authority (with her jokes, her cajoling, her asides) until the audience shares the journey with her.

5 In this play, the audience is constructed as a kind of witness as Djanet recounts key life experiences, from when she was a child and taunted and ostracized by her friends, to her trip to Africa, where she finds community and connection in unexpected places. In this way, the "folk" history of standpoint positioning is experienced: where personal story is valued and the knowledge of an oppressed individual gains currency. The access to this knowledge is facilitated by the audience-stage relationships that are cultivated. The fourth wall is frequently broken and the audience is directly addressed, establishing a notable intimacy. As Reid Gilbert suggests, "[in] one-person shows the distance between performer and spectator seems somehow smaller regardless of the size of the auditorium" (6). In Afrika Solo, for example, this intimacy is produced through a confession: "I am a T.V. nut, no a T.V. addict" (22). She then engages the audience in a game of name-that-theme-song using TV science fiction shows (22-24). She cajoles them as she would a reticent friend, "You’re kidding?" she says,and "Oh, come on!" as she tries to get a response to her clues (24). Djanet’s approach stands in stark contrast to the "god-trick" that Haraway describes. There is nothing omniscient here, but rather the guilty pleasures of popular culture. The play becomes cabaret-like, at times, as Djanet raps and rhymes her way through her adventures, supported by musicians. Within the narrative of Djanet’s journey, other choices are made which support this intimacy: the audience is privy to her romantic adventures and private thoughts. Most importantly, they witness Djanet’s renaming of herself after a city: "The oasis town of Djanet. D.J.A.N.E.T. It means paradise in Arabic" (49). Her recognition of self is made explicit and confirmed near the end of the play, again by drawing on a shared knowledge with the audience, "You know sometimes when you look into the mirror and you sorta’—catch your own I (sic)" (93). In this way, Djanet not only legitimizes her "standpoint" position, but she also makes sure that the audience takes on the same vantage point. She situates herself in an intimate relationship with the audience, affirming her identity through an assumed shared ground of experiences and knowledge. The relationship posited with the audience is relentlessly optimistic, good-humoured, and inclusive. We want to be on her side.

6 The play flirts with essentialism. Djanet says, echoing Ntozake Shange, "The base of my culture would be forever with me. And funny thing is, it always had been. In my thighs, my behind, my hair, my lips" (91). The affirmative ending of the play is a celebration of wholeness: "Inside my African soul / Is where I found the light / That makes me feel right, makes me / whole" (92). Furthermore, the play depends upon the virtuosity of its singer/actor/author. This is Djanet’s story and its rests on her own personal charisma. Other actors onstage (and other perspectives) are tangential to the performance of Djanet Sears herself.

7 But Djanet’s performance is always foregrounded.A pact with the audience is activated and a process of "performative auto/biographics" is engaged. As Sherrill Grace says, "performance enacts the performative in that the performer changes, adjusts, modifies identity and life-story in the process of playing the part and we are able to watch and possibly learn that identities need not be prescribed, interpellated, and fixed" (10). Depending on the performative dimension, Sears might be self-consciously quoting Shange’s lines from the introduction to for coloured girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf: "With the acceptance of the ethnicity of my thighs & my backside, came a clearer understanding of my voice as a woman & as a poet" (xv). Ultimately, the fierce way that Sears wields and manipulates multiple cultural references prevents an essentialist vision of identity. Joanne Tompkins sees the metaphor of "rehearsing" as being predominant in Afrika Solo, suggesting that "rehearsal" is privileged over performance:The primacy of the performance text continues to be deferred, in fact pushed off the stage altogether as an epistemological irrelevance: Djanet is constantly rehearsing her part, as she learns more about who she really is, adopting another name,doing all the things that an actor rehearsing a role would do. (36)In this way, just as Sears blurs the subject/object divide by acknowledging her multiple roles in the piece, she also mixes essentialist articulations with performative interventions. In particular, Sears foregrounds the performance of identity as she herself plays many different characters (her friend VD, her mother and father, even a man she meets in a bar). By doing this, she acknowledges the way in which she has embodied these interactions (emphasizing the situatedness of knowledge) and the ways in which she has read herself through their eyes. She undergoes a metamorphosis through the use of clothing onstage, transforming her baggage into costume. The final image left of Sears is a hybrid, layered one: in jeans and t-shirt, with her African dress over top. Her ultimate recognition of self comes through song, when she sings "O Canada" to the BamButi people, in a gospel style. "That’s it! See, that’s me! The African heart-beat in a Canadian song" (88). This idiosyncratic version of "O Canada" adds an emotional, excessive dimension that is about performance and interpretation.

8 And again, the script itself marks the playwright’s agency in identity formation. We see her name as author as Djanet Sears, but the cast list refers to her as Janet/Djanet and speeches and dialogue are also marked this way, depending on where she is in this process of transformative re-naming. The reader is signalled as to the playwright’s agency in determining her own identity and in her own knowledge creation. By the end of the play, Sears, in catching her own ‘I’ [sic], is articulating an affirmation of this feminist standpoint positioning, in which she recognizes the legitimacy of a situated knowledge and in which object and subject are not split, but rather fused.

9 Where Afrika Solo is the fictionalizing of a true story, Harlem Duet takes a fictional text as its point of departure for further imaginings: the play is a prequel to Othello. The main character, Billie, is Othello’s first love, a black woman—Billie is a reference to the "sybil" who sewed the handkerchief in Shakespeare’s text (3.4.51-68). Shakespearean characters hover about the play, as if waiting for the real Othello to begin: we catch a glimpse of the arm and hair of Othello’s new love, Mona (Desdemona), and Chris Yago is Othello’s dubious colleague. Othello is an academic, recently engaged to head the department’s summer courses in Cyprus, a choice which has caused some controversy among colleagues.

10 The play is located, in many ways, at the intersection of Martin Luther King and Malcom X, both geographically (the Harlem intersection where their apartment is located) and ideologically (in the positions that Billie and Othello take up regarding race and their relationship). Billie, who has spent years putting Othello through school, resents his abandonment of her for a white woman. She accuses Othello of loving Whiteness and betraying Blackness. Othello presents an assimilationist position: "Things change, Billie. I am not my skin. My skin is not me" (74). At the same time, he says that he prefers white women: "They are easier–before and after sex. [. . .] We’d make love and I’d fall asleep not having to beware being mistaken for someone’s inattentive father" (71). In this presentation of points of view then, Harlem Duet is much more contradictory and confrontational in its approach than Afrika Solo.

11 The relationship between Billie and Othello is set in a present time, uses realistic action and dialogue and is the main focus of the play. There are two other more stylized narrative threads which are interwoven in the text to complicate again the presentation of "knowledge," especially as experienced by oppressed peoples. These stories have explicitly tragic outcomes which indicate the male protagonist’s downfall after his abandonment of a black woman for a white woman. In the 1860s sequences, HIM and HER are slaves who plan to escape to Canada, but HIM decides he can’t abandon his mistress, Miss Dessy. Eventually we find HIM hanged. In the 1928 sequences, HE is a minstrel who longs to play Shakespeare, forsaking SHE for a white woman. His throat is slit by SHE.

12 As in Afrika Solo, Sears walks the line between essentialist and constructivist versions of identity. In what could be viewed as a universalizing move, the two main actors who play Billie and Othello also play HE and SHE and HIM and HER in the other time sequences, reminding the audience of the ways this story is replayed and of its inevitability. On the other hand, these story lines are much more stylized, in both the names and the language used, and constantly interrupt the linear narrative of the Billie/Othello story line. Furthermore, a complex soundscape of the play foregrounds the cultural and social fabric from which these depictions emerge. Excerpts from speeches of black activists, from news items, from jazz and blues music, as well as an original score for cello and bass introduce and accompany scenes. The ongoing framing of the action reminds the audience of the social nature of identities.

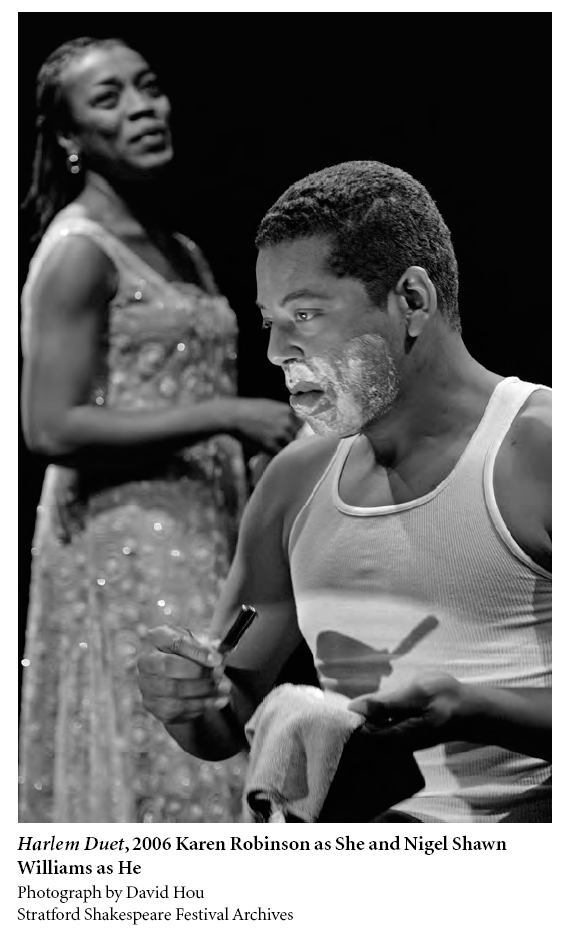

Harlem Duet, 2006 Karen Robinson as She and Nigel Shawn Williams as He

Display large image of Figure 1

13 Instead of embracing the audience, or engaging with them in the confessional/conspiratorial play of Afrika Solo, Harlem Duet keeps its audience at a distance and, in its frustration of access to the "god trick," demonstrates the challenges of feminist standpoint positioning: what happens when points of view are put into opposition? How productive can paradoxical thinking be? This is perhaps most clearly realized in the different audience-stage relationship that characterizes Harlem Duet. Rather than explicitly engaging the audience with the largely accessible mainstream popular culture references of Afrika Solo and charming them into seeing her point of view, Sears positions Harlem Duet differently. The play assumes an intimate knowledge of Shakespeare’s Othello and offers a complex, hybridized fabric of explicitly black references from history, music, and popular culture. Although the play seems to privilege Billie, as protagonist, and in her anti-assimilationist position, this is also compromised. The soundscape, for example, becomes more distorted as she becomes more distraught and confused,echoing her state of mind in an expressionistic way. But it is not always easy to side with Billie; the choices she makes are not easily sympathetic. After all, she plots to poison Othello in a vengeful act. And Othello, on the other hand, makes some compelling arguments. In an interview, Sears expresses her desire to be ambivalent:[...] one of the things that I was always excited about during the production was the kind of discussions that would happen after the play. People would tell me stories about talking all night, arguing all night about who was right and who was wrong. People would go to the play and not have the same opinion of what the writer’s intention was. I loved that. Hopefully it’s a duet, and what I do is stay that line, I stay that course right on the edge and have people have to confront and make choices about who’s right, who’s wrong, who’s flawed. (Buntin)It is not only through the content, but also through the form of the play that Sears engages in this duet with the audience. Although the present-day story line is linear, the others are not. The 1928 sequence in particular is erratic, resisting a chronological reading. Some narrative details are repeated from thread to thread. Others are dropped. Some answers to questions are clear. Others are not. Margaret Kidnie suggests that "The dramatic structure of Harlem Duet fosters the unshakeable belief that the scenic fragments can be reassembled as a narrative unity, while at the same time denying the satisfaction of seeing that goal ever accomplished" (36). This denial paradoxically increases the audience’s engagement in the issues by imitating the frustration Billie and Othello experience. Kidnie says, "The structural indeterminacy of Harlem Duet unsettles efforts to ignore or falsely patch over the lack of shared ground between Billie and Othello; more than that, it enables the realization that there exists an excess beyond what they—and we—are currently able to communicate" (36). Whereas Afrika Solo makes an inclusive move towards the audience, involving and guiding them towards a single, celebratory conclusion (however performative), Harlem Duet interrogates, divides, and challenges the audience, involving them, perhaps, to the extent they know the ur-text of Othello and the soundscape references, but denying them any single, agreed-upon alliance, not only with the characters, but also in ideological positioning, time, and history. The aporia that Harlem Duet presents is very different from the unity demonstrated in Afrika Solo.

14 Related to these different audience-stage relationships is, of course, genre. In the "Afterword" to Afrika Solo, Sears describes how she follows a traditional West African genre called "Sundiata Form": "Traditional West African theatre consists of a story being told through narrative, music and dance" (96). Before going on to describe the play as autobiomythography, Sears quotes bell hooks at the beginning of the Afterword:The longing to tell one’s story and the process of telling is symbolically a gesture of longing to recover the past in such a way that one experiences both a sense of reunion and a sense of release. (95)This reunion and release are achieved in Djanet’s recognition of her ability to communicate across cultural boundaries, as she discovers when she sings "O Canada" (88). But Afrika Solo also has the elements of a traditional Western comic structure. And just as Sears seems to invoke and question simultaneously an essentialist view of identity, here she uses genre ironically. The play is framed by a love story. Djanet has left her lover, Benoit Viton Akonde, at the beginning of the play, and a comic structure would demand that she reunite with him at the end. Throughout the play, the courtesy phone rings periodically, and we know it is Ben calling for Djanet. When she finally does speak to him, she tells him that she loves him, but that she cannot marry him and that she must leave. The comic marriage denied, the journey of this story is only perversely comic: a re-union of one prevails over a union of two.

15 As a "rhapsodic blues tragedy," Harlem Duet is a hybrid form, as Ric Knowles points out, "that links tragedy with jazz, high-Western with Black culture even as its musical bridges perform blues on orchestral strings" (150). The tragic mode of Shakespeare’s Othello is evoked, certainly by the two sequences in the past. The present sequence is more inconclusive, "on the edge," as Sears puts it, in the same way that our readings of the debate between Billie and Othello are. Throughout the play, Billie has been preparing potions, using Ancient Egyptian remedies, in order to produce a poison which she pours on the handkerchief. But Billie accidentally touches her face with her gloved hand that has the poison residue (93). It is unclear whether Billie has managed to poison herself and whether this causes the ensuing deterioration in her mental condition. She leaves the handkerchief in a box for Othello to pick up, but then changes her mind and asks her father to throw it out; however, Othello finds it and takes it out of the box. Has Othello been poisoned, despite Billie’s last minute efforts to prevent this? Is the final scene indicative of a severe decline in her condition, or a sign of hope that she’s receiving the help she needs? The play is on the verge of tragedy because the outcome of these actions is never really clear.

16 The final scene of the play shifts location from their apartment (as Billie is packing up and dividing possessions after Othello has moved out) to the waiting room of a psychiatric hospital where Billie has been admitted as a patient. The parameters of knowledge change, from the private to the public, from the potions of Ancient Egypt to the modern Western psychiatric talking cures. Although it appears as if Billie’s condition is deteriorating, there are elements of hope. Billie’s father, Canada, who wasn’t around much when she was young, has now come to be with her, and the last words of the play are his: "I don’t think I’m going anywhere just yet—least if I can help it.Way too much leaving gone on for more than one lifetime already" (117). When he first arrives in Harlem, Billie makes them tea: "Tea should be ready," says Canada."Shall I be mother?" (80). The abandoning father has become the nurturer. And significantly, hope appears in reconciling differences between the sexes rather than entrenching and exacerbating them. In Canada’s appearance in the play, Margaret Kidnie reads this"hope"in the genre of the play and as an extension of the Pericles reference in the 1920s sequence (which Othello has been cast in): "[...] Sears evokes the bitter-sweet tone of Shakespeare’s late plays, a genre positioned between comedy and tragedy, to suggest that there exist possible—albeit as yet indiscernible—ways forward for her protagonist" (41).

17 The hybridity of the form of Harlem Duet may be considered another example of the ways in which feminist standpoint theory and its contradictory knowledges are positioned. Although the outcome is ambivalent, the swelling of support for Billie is significant, and there is "hope": if not explicitly for Billie, then for the future. Other characters seem poised for a renaissance. Magi, Billie’s landlady, seems to find in Canada the mate she’s been looking for and a potential father for the baby she wants to conceive. Amah and Andrew are also trying to have another child; Amah is ten days late in getting her period, as we find out near the beginning of the play. The play provides neither the celebration of comedy, nor the catharsis of tragedy, but again, rather ironically engages the audience in tragic conventions, only to withhold any simple resolution.

18 Standpoint positioning is also apparent in the ways in which nationhood and citizenship figure in the plays. Afrika Solo is set in an airport, and the model of nationhood it puts forward at first appears similarly transitional. Djanet holds four passports: Canadian, British, Guyanese, and Jamaican (40). But, as Anne Nothof suggests, "the airport replicates ‘Canadian’ cultural experiences, with voices in English and French announcing flights and paging travellers" (206). Djanet comes closest to a recognition of what her nationality means when she proclaims "the African heartbeat in a Canadian song" (88). Afrika Solo recognizes the experience and impact of oppression, but finds solace in the narrative of the self as a truth-speaking, self-sustaining individual, however "performatively" enacted. Harlem Duet, on the other hand, presents a more complicated understanding of citizenry and identity.In particular, it is more firmly situated within the African-American experience, as George Elliott Clarke suggests in "Contesting a Model Blackness," returning to America for "a way of conceiving and organizing African-Canadian existence" (2). The soundscape presents largely American references (Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Michael Jackson) and yet, in their veering off into discord, they may represent another perversion. Clarke describes the difference of African-Canadianité1 as "a condition that involves a constant self-questioning of the grounds of identity" (26), a perversion of the African-American model. Peter Dickinson suggests that Harlem Duet engages in this ambivalence in its referencing of Billie’s father, Canada (he comes from Nova Scotia). Dickinson suggests it is a reminder "that there are other historically entrenched—if geographically marginal—Black communities in North America besides Harlem" (194). Although, as Ric Knowles says, the play "is not concerned with Canada or Canadian cultural nationalism as such" (151), the complications and tensions of difference are acknowledged and emphasized in these ways in the play and indicate another way in which agency is made more difficult.

19 Distinguishing both plays, of course, is an emphasis on the journey of the female protagonist. In We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, bell hooks links a negative representation of black masculinity to a patriarchal culture: "wise progressive black women have understood for some time now that the most genocidal threat to black life in America, and especially to black male life, is patriarchal thinking and practice." (134). To a certain extent, these plays have an Afro-gynocentricity similar to what George Elliott Clarke notes in the plays of George Boyd: "His plays enact [. . .] an Afro-gynocentric Darwinism, in which Black women represent ‘the survival of the fittest,’ while the primary Black male characters appear as sly, cringing, obsolete sell-outs" ("Afro-Gynocentric" 78). There is something of a similar gynocentricity in these plays by Sears, although more tempered and not quite so Darwinist as Clarke suggests about Boyd’s work.

20 Afrika Solo, for example, is clearly Djanet’s play, and any other characters, male or female, necessarily appear as aspects of herself, as constructions of her own making in what amounts to a therapeutic journey. In the list of characters at the beginning of the play, for example, the musicians who play a number of secondary roles are listed simply as Man One and Man Two. Even in the other roles she performs, Djanet often editorializes in her own voice afterwards: "(He’s probably never seen a black North American woman in his life)" she says after performing the role of a chief tourist officer (50). Djanet’s most significant relationship, with Ben, is represented mostly through voice-over and phone calls. Benoit Viton Akonde, she tells us, is a prince; his great-grandfather was a king. A prince? A proposal of marriage? Perhaps Djanet’s refusal is the patriarchy narrowly averted.

21 Harlem Duet, on the other hand, presents characters and gender roles more ambiguously, suggesting that we don’t know everything, that we don’t see everything. Billie’s brother, Andrew, a good brother and father, seemingly a strong, stable presence in their lives, is never seen. We only see his wife, Billie’s sister-in-law, Amah. Billie’s father, as already mentioned, is a somewhat recuperated abandoning father, as he remains to look after Billie. As for Othello, the differences that Sears makes in her revisioning of Shakespeare’s text are striking, especially in the shift from Othello as warrior to Othello as academic. One critic suggests that "Sears reconfigures Shakespeare’s protagonist as an assimilated black ‘achiever’" (Thieme 85). Perhaps this exchange of weapons for words indicates a cultural shift, but I suggest that there is another way of reading this rendering of Shakespeare’s Othello. Though "rude" in speech (1.3.81), Shakespeare’s Othello nonetheless manages to seduce Desdemona with his stories nonetheless. The erotics of violence and the erotics of education are linked. This relationship and the seduction of knowledge persist in Harlem Duet. Othello says, "Our experiences, our knowledge transforms us.That’s why education is so powerful, so erotic. The transmission of words from mouth to ear. Her mouth to my ear. Knowledge. A desire for that distant thing I know nothing of, but yearn to hold for my very own" (73). The tables of seduction are turned, however, becoming a perversion of the Shakespearean text, as Mona now tells stories to seduce Othello. Sears uses this twist to explain the assimilation of Othello. Is this why we see Othello at his worst, undone by Mona as Iago undoes Shakespeare’s Othello, also enacting this through the stories he tells? Education and progress are clearly linked to "whiteness" throughout the play. Billie says, "But progress is going to White schools. . . proving we’re as good as Whites...like some holy grail...all that we’re taught in those White schools. All that is in us. Our success is Whiteness. We religiously seek to have what they have.Access to the White man’s world. The White man’s job" (55). The impact of this "education" on Othello is severe and perhaps most clearly articulated in how he responds to Mona’s influence. Othello has been seduced by whiteness. We see him break his marriage bond with Billie, a sacred bonding ritual from times of slavery, which they performed when they first got their apartment together. Although it’s clear that he misses her (they have sex when he comes to pick up things from the apartment), when Mona calls on the apartment intercom unexpectedly and speaks to Othello, he is completely dominated by her. She doesn’t have to say anything. He hastens to leave.We see Othello as powerless, and "Billie," the stage directions indicate, "is unable to hide her astonishment" (61). The next time Othello comes to the apartment, he tells Billie that he and Mona are getting married.

22 But a Darwinist reading of Billie as the strong black woman and Othello as the weak black man (who succumbs to the white woman) is not forthcoming. Billie, as she poisons the handkerchief with Ancient Egyptian remedies, is also prone to bad behaviour. And she herself is not immune to the seduction of knowledge and academia. In a conversation with Magi, she makes fun of Othello, presumably turning discursive constructions back on him, parodying even her own thesis work, perhaps: she pronounces his condition, "Corporeal malediction. [...] A Black man afflicted with Negrophobia." "Girl, you on a roll now!" says Magi. "A crumbled racial epidermal schema [...] causing predilections to coitus denegrification," says Billie, a sentence which Magi interrupts with "Who said school ain’t doing you no good" (66). Billie is, after all, a graduate student herself. The soundscape may provide a kind of counter-discursive measure against the dominance of the white academia that Billie and Othello are engaged with; speeches from prominent black activists respond,to a certain extent, to the drama being played out by Billie and Othello. And yet, as Ric Knowles points out, the voice-overs are largely male voices, and "we hear Billie only through the filter of a Black history that tends to erase her. But the barrage of male voices also threatens to contain the play’s Black feminist interventions within a normalization of the male voice as the voice of History and Culture" (158). The history of Billie’s resistance is not found in the foreground, in the sound-scape, but rather is embedded, in a muted way, in the dialogue of Billie, HER, and SHE. "Aint I a woman," Billie says to Othello, evoking Sojourner Truth’s famous speech. In a 1928 tableau, as SHE holds HE after having sliced his throat with a razor blade, SHE starts to sing "Aint no body’s business if I do," a Billie Holiday song (72), whose name also resonates with her own.

23 Just as Othello seems to succumb to Mona’s influence, however, Billie cannot shake Shakespeare’s. In an interview, Sears describes her approach in writing Harlem Duet: "[. . .] while I can challenge Shakespeare, in truth, he’s really a part of me. I’m part of this culture. It’s part of the foundation of my own mythology, so me challenging Shakespeare is me challenging God, in terms of literature, because it’s something that exists inside of me" (Buntin). Although she is part of this "prequel," Billie also has much in common with characters from Shakespeare’s Othello. Like Iago, she manipulates the handkerchief from a sign of love into a sign of betrayal. Like the original Othello, she is the one who seeks vengeance on a lover and descends into a kind of madness. The trance-like state which Othello enters is where we find Billie by the end of the play, in the psychiatric hospital: like Othello, distracted; like Desdemona, singing remembered songs. Desdemona in her bedchamber tells Emilia about a song her mother’s maid Barbary sang: "She was in love," says Desdemona. "And he she loved proved mad / And did forsake her" (4.3.27-28): a good description of Billie’s condition. In the psychiatric ward, Billie sings a children’s song with Magi, reminiscent of this melancholic moment between Desdemona and Emilia (114-16). Thus Billie, with her ambiguous nickname (male? female?), incorporates aspects of several characters from Shakespeare’s Othello. Like genre and structure, character challenges easy categorization. As an "outsider within," Billie plays her part, but cannot fully access the world of Shakespeare and, perhaps, the cultural values associated with him.

24 In Harlem Duet, standpoint positions are again foregrounded and problematized more. George Elliott Clarke warns against how "worrisomely, Sears replicates Cleaver’s sexist racial archetypes,2 primarily his sketch of the ‘Ultrafeminine’ (the white woman) and the ‘Supermasculine Menial’ (the black man) [. . .] to lobby for black, heterosexual solidarity" ("Treason" 191). However, he also insists that the chief value of Sears’s play is "that it stages actual cultural debates occurring in Black Canadian communities" ("Treason" 191). Clarke notes Sears’s "scrupulous fidelity to a ‘black-bottom’ empirical realism. The dialogue between Billie and Othello echoes conversation that can be (over)heard in any intra-black community debate about race and belonging in Canada" ("Treason" 192). Clarke uses the words of John Fraser to describe how Sears "has turned her gaze‘as firmly and in a sense disinterestedly as possible on concrete human behaviour’" (192). What Clarke calls an "empirical realism" could also be read as an emphasis on a standpoint positioning, as Sears brings into juxtaposition two particular, embedded points of view and their differing responses to their situations. As noted above, Sears also demonstrates some of the difficulties in standpoint theorizing. Billie’s and Othello’s points of view are both strongly articulated and seem irreconcilable. It is also possible to read Othello as an "outsider-within" who suppresses his difference and attempts, instead, to become a "thinking as usual" insider (Collins, "Learning" 122). Othello still engages with what Nancy Hartsock calls an "abstract masculinity." As Hartsock explains,[. . .] the male experience is characterized by the duality of concrete versus abstract. Material reality as experienced by the boy in the family provides no model,and is unimportant in the attainment of masculinity. Nothing of value to the boy occurs with the family and masculinity becomes an abstract ideal to be achieved over the opposition of daily life. Masculinity must be attained by means of opposition to the concrete world of daily life, by escaping from contact with the female world of the household into the masculine world of public life. (45)In the largely realistic world of the Billie and Othello thread, spatial configurations reiterate Hartsock’s points. Billie’s world is the world of the apartment, where their marriage was consecrated, where possibly the frozen aborted foetus exists in the freezer, where sex once more affirms their communion. Othello, on the other hand, is in the process of abandoning this domestic space, more and more pulled into the public world represented by Mona and her colleagues. Billie herself does not negotiate the tension between inside and outside with ease,as seen in her relationship to academia (and in her character’s relationship to Shakespeare). And yet Billie’s engagement always takes into consideration the domestic and the local whereas Othello denies this domestic positioning. His thoughts, his aims, even his phone calls are located on the larger academic community and what Cyprus represents instead. The final scene, the only scene in this narrative strand which takes place outside the apartment, is ambiguous: possibly a place of healing, possibly a place where the "flashing" blue eyes (115) of the doctor (a white woman) again determine the perspective which predominates. Banished from Shakespeare’s Othello, and with limited positive impact in the world of Harlem Duet by its conclusion, Billie is left adrift, and this presents perhaps the most challenging aspect of feminist standpoint positioning. Situated, contingent knowledges only gain the currency of "accuracy" in realms which are ready to hear and acknowledge them. In Afrika Solo, Sears can seduce us into seeing her point of view by creating a space of knowledge that we occupy with her. In Harlem Duet, she lays bare contradictions. This is the challenge, perhaps, of feminist standpoint positioning, especially from an "outsider-within" position: it’s a lonely place to be. In We Real Cool, bell hooks uses the myth of Isis and Osiris as a suitable metaphor for the black diaspora and, in particular, for relations between black men and women. Isis re-members her partner’s body, putting the dismembered body back together until he is whole again.hooks says, "This myth provides a healing paradigm for black females and males who have suffered so long because of the myriad ways we are psychically ‘dismembered’ in a culture of domination. It invites us to use our imaginations therapeutically,to take myth and re-vision it in our image" (161). Where Afrika Solo foregrounds a process in which "wholeness" is performed and where the audience witnesses, Harlem Duet emphasizes a process whereby dismembered fragments are acknowledged, domination resisted,and where the audience is encouraged to participate in the healing process of imaginatively re-membering.

Works Cited

Buntin, Mat. "An Interview with Djanet Sears." Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project. University of Guelph. 17 May 2004 <www2.uoguelph.ca/dfischli/i_dsears.dfm>.

Clarke, George Elliott. "Contesting a Model Blackness: A Mediation on African-Canadian African Americanism, or the Structures of African Canadianité." Essays on Canadian Writing 63 (Spring 1998): 1-55.

— . "Afro-Gynocentric Darwinism in the Drama of George Elroy Boyd." Canadian Theatre Review 118 (Spring 2004): 77-84.

— . "Treason of the Black Intellectuals?" Odysseys Home: Mapping African-Canadian Literature. Ed. George Elliot Clarke.Toronto: UTP, 2002. 184-210.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Fighting Words: Black Women & the Search for Justice. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1998.

— . "Learning from the Outsider Within." Harding, Feminist Standpoint 103-26.

Dickinson, Peter. "Duets, Duologues, and Black Diasporic Theatre: Djanet Sears, Willliam Shakespeare, and Others." Modern Drama 45.2 (Summer 2002): 188-208.

Gilbert, Reid. "‘You’ll Become Part of Me’: Solo Performance." Canadian Theatre Review 92 (Fall 1997): 5-9.

Grace, Sherrill. "Performing the Auto/Biographical Pact: Towards a Theory of Identity in Performance." 24 May 2004 <http://www.english.ubc.ca/faculty/grace/thtr_ab.thm>.

Harding, Sandra. "Introduction: Standpoint Theory as a Site of Political, Philosophic, and Scientific Debate." Harding, Feminist Standpoint 1-15.

— , ed. The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader: Intellectual and Political Controversies. New York & London: Routledge, 2004.

Haraway, Donna. "Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective." Harding, Feminist Standpoint 81-101.

Hartsock, Nancy C.M. "The Feminist Standpoint: Developing the Ground for a Specifically Feminist Historical Materialism." Harding, Feminist Standpoint 35-54.

hooks, bell. We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity. London: Routledge, 2004.

Kidnie, Margaret Jane. "Seeing Beyond Tragedy in Harlem Duet." Journal of Commonwealth Literature 36.2 (2001): 29-44.

Knowles, Ric. "Othello in Three Times." Shakespeare and Canada: Essays on Production, Translation, and Adaptation. Brussels: Peter Lang, 2004. 137-64.

Nothof, Anne. "Canadian‘Ethnic’Theatre: Fracturing the Mosaic." Siting the Other: Re-visions of Marginality in Australian and English-Canadian Drama. Ed. Marc Maufort and Franca Bellarsi. Brussels: Peter Lang, 2001. 193-215.

Sears, Djanet. Afrika Solo. Toronto: Sister Vision, 1990.

Sears, Djanet. Harlem Duet. Toronto: Scirocco Drama, 2002.

Shange, Ntozake. for coloured girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf. New York: Bantam, 1981.

Shakespeare, William. Othello. New York: Penguin, 1998.

Thieme, John. "A Different‘Othello Music’: Djanet Sears’s Harlem Duet." Performing National Identities: International Perspectives on Contemporary Canadian Theatre. Ed. Sherrill Grace and Albert-Reiner Glaap. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2003. 81-91.

Tompkins, Joanne. "Infinitely Rehearsing Performance and Identity: Afrika Solo and The Book of Jessica." Canadian Theatre Review 74 (Spring 1993): 35-39.

Notes