Articles

The Westminster Opera House:

A Cultural and Economic Disappointment1

Kevin Barrington-FooteUniversity of British Columbia

Abstract

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most towns in Canada boasted an "opera house." In fact, very little opera was put on the boards; the name was a euphemistic marker of the community’s cultural and economic maturity. The Westminster Opera House (1899-1926) is, like most other opera houses, long since gone and virtually forgotten. This article recounts for the first time the story of the venue and its unsuccessful efforts to become a viable cultural and economic enterprise. Several factors likely contributed to the theatre’s lack of success, not the least of which was the proximity of the younger, burgeoningVancouver. All in all, the Westminster Opera House failed to realize the hopes of its founders and must be counted amongst the city’s disappointments.Résumé

À la fin du dix-neuvième et au début du vingtième siècle, on trouvait un opéra dans pratiquement toutes les villes canadiennes. Dans les faits, il était rare que des œuvres d’opéra figurent au programme de ces établissements; leur nom servait à marquer par un euphémisme la maturité culturelle et économique des collectivités en question. Comme la plupart des autres établissements de son genre, la Westminster Opera House (1899-1926) a fermé ses portes depuis longtemps et a pratiquement été reléguée aux oubliettes. Barrington-Foote rappelle pour la première fois l’histoire de ce lieu et les efforts infructueux qui ont été déployés pour en faire une entreprise viable sur les plans culturel et économique. Plusieurs facteurs ont probablement contribué à cet échec, dont la proximité de Vancouver, une ville plus jeune et en plein essor. Somme toute, le rêve des fondateurs du Westminster Opera House n’a pas été réalisé, et leur projet compte parmi les grandes déceptions qu’a connues la ville.1 In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries most towns across Canada and the United States boasted an opera house. Relative to comedies, dramas, and other forms of entertainment, little opera was in fact staged, particularly in the smaller towns (Kallman 297). The designation "opera house" was used euphemistically as an "icon of cultural coming of age and economic progress and the community’s self-conscious desire for a symbol of such maturity [...]" (Rittenhouse 72). Although most opera houses have long since disappeared, revisiting them provides a window through which to view those communities. The Westminster Opera House, virtually a forgotten venue, affords us a glimpse of the cultural life in New Westminster, BC in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

2 On 9 March 1899, the day following the highly successful opening of the new theatre in New Westminster, BC—also known as the Royal City because it was named by Queen Victoria—an editorial in the local newspaper proclaimed that the Westminster Opera House would provide "a valuable advertisement and a distinct material acquisition to the city, saving many dollars from going out of the city, which formerly went out in seeking legitimate amusement elsewhere [Vancouver]; for now, the best companies that come to the coast will perform here, also, a thing that was impossible before" (Columbian, 9 March 1899: 2).2 As will be demonstrated, the expectations for the new venue were never realized. Throughout the two decades of its existence, the Westminster Opera House struggled to bring in audiences and ultimately failed in its promise as a cultural and economic boon to the Royal City. The first part of this article is narrative, recounting for the first time the story of the Westminster Opera House. In so doing, it contributes to the literature on old opera houses in Canada and to the need for ongoing empirical research in theatre studies (Conolly 153). The latter part of the article attempts to explain the Opera House’s failure in terms of regional and national (and international) developments.

3 The fact that the Westminster Opera House has been virtually ignored to date reflects the relative lack of attention paid to the city of New Westminster, the "disappointed metropolis" (Gresko & Howard 11). The cultural and economic development of the Royal City was affected in no small measure by its proximity to Vancouver and more will be said of this at the end of the article. With respect to studies of old opera houses across Canada, British Columbia generally has not fared as well as Ontario or the Prairies (see a number of articles in the list of sources). But Victoria, Vancouver, and even other centres in the Northwest have attracted some attention (see especially Booth; Elliott, Craig; Elliott, E.C.; Todd). Apart from the work of Evans and McIntosh, the same cannot be said for New Westminster. The Westminster Opera House itself is described briefly in Evans’s Frontier Theatre but is not mentioned in the Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre or in the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. In the 1990s, Archie Miller, then curator of Irving House Historic Centre and Museum, wrote three short articles in a local newspaper, the Royal Record, in support of the present investigation.

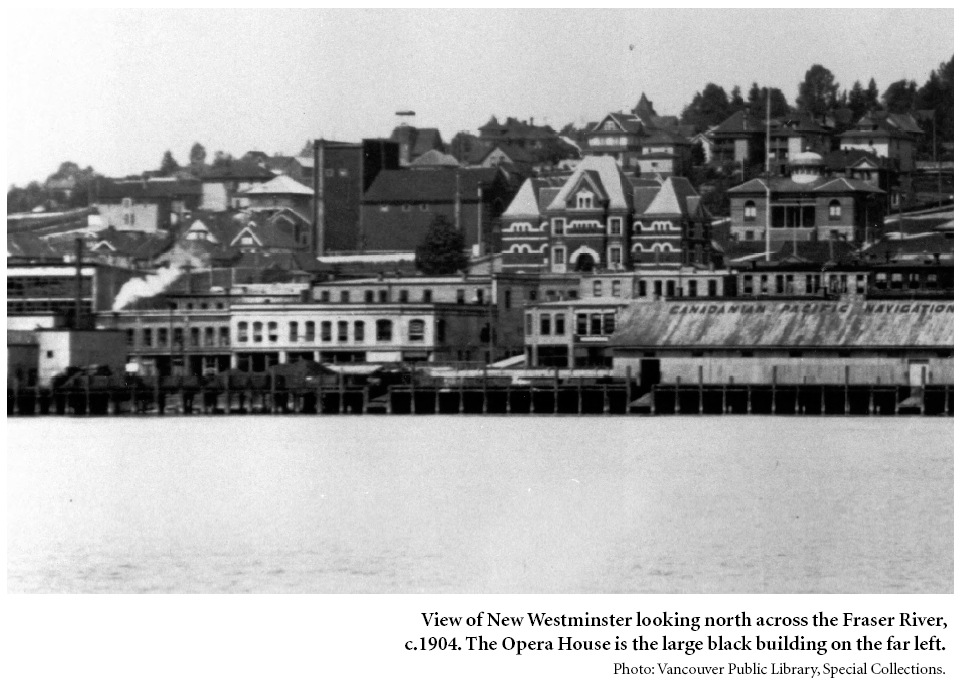

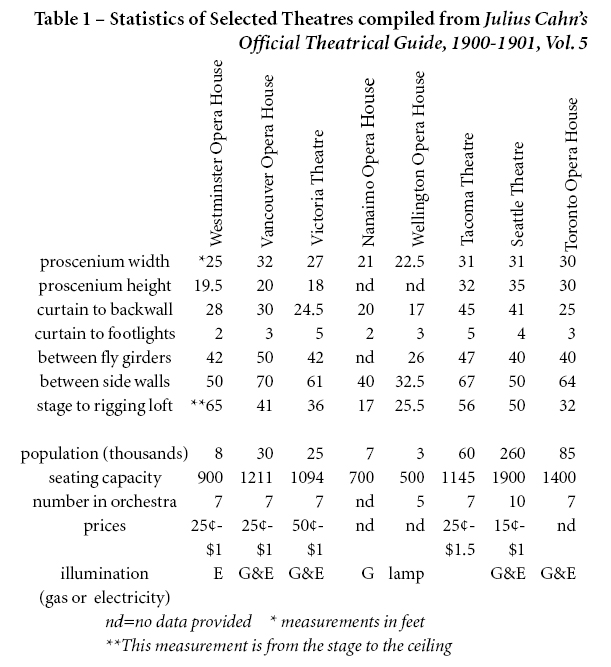

4 Of the physical structure itself, nothing remains save some seats in the Irving House Centre and Museum (though the provenance of those seats cannot be confirmed). Of the few photographs in which the Opera House can be seen, it is only from a distance (see photograph below). Despite the paucity of sources— a common problem for theatre historians (Saddlemyer 16)—a systematic mining of the local newspaper, city maps, council minutes,and other documents enables one to trace in considerable detail the trajectory of the theatre and its offerings.

5 On 10 September 1898, fire razed most of New Westminster, including Herring’s Opera House, built by a local druggist in 1887. There has been as yet no study of Herring’s so it is not possible to evaluate fully the theatre itself and its offerings. A glance at a few of the Columbian newspapers of the 1890s reveals that it brought to New Westminster the same variety of theatrical fare—dramas, comedies, specialty acts, etc.—that were booked by other theatres in the Pacific Northwest (Todd, "Organization" 4-5). If we are to believe the promoters of the new theatre (Westminster Opera House), Herring’s was, however, not altogether satisfactory and was not always able to accommodate the best productions (see below). In these cases New Westminsterites were able to take in shows in Vancouver by riding the Inter-Urban Railway. The trip took only about thirty minutes and the Railway put on late cars for the ride home. Moreover, audiences could enjoy the luxury of the Vancouver Opera House built by the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1891 at a considerable cost of $100,000. In the rebuilding of New Westminster after the fire, a group of enterprising citizens saw a cultural and economic opportunity for New Westminster. A new theatre, a "comfortable and commodious place of public amusement" (Columbian, 22 October 1898: 4), would raise the city’s profile as a stop on the theatrical circuit and keep dollars at home.

6 At a meeting on the evening of 21 October 1898, a small group of members of the City Band, proposed to form a joint stock company with a capital stock of $5000 in $100 shares (Columbian, 22 October 1898: 4). In less than a month, by the middle of November the architect, Emil Guenther, had almost completed the drawings, lumber had been ordered, a provisional Board of Directors had been elected, and tenders were opened.

View of New Westminster looking north across the Fraser River, c.1904. The Opera House is the large black building on the far left.

Display large image of Figure 1

7 The new theatre was erected on the corner of Lorne and Victoria Streets, two blocks north of Columbia Street, at that time the commercial centre of the city, and was amply described in the Columbian (7 November 1898: 4; 2 March 1899: 1; 8 March 1899: 1). From the exterior the building was singularly unattractive, which might account, at least in part, for the lack of photographs. Constructed at a cost of approximately $10,000—considerably less than the Vancouver Opera House—the Westminster Opera House was a plain wood frame building, approximately 50 feet by 100 feet, and two-and-a-half storeys tall. Attached to the Opera House was an Assembly Hall that was rented out for sundry purposes. The main entrance on Lorne Street led into an anteroom or lobby 18 feet by 20 feet, with a cloakroom on the left and the box office on the right. On both sides staircases led to the gallery. The orchestra was 50 feet by 50 feet, the floor of which was inclined 4 feet in 42. At the rear of the orchestra, as one entered from the anteroom, was a corridor from which ran three aisles to seating for somewhere between 450 and 500 people. Although boxes were planned and provided for, they were not installed until some years later (Columbian, 26 October 1909: 5). The stage measured 30 feet by 50 feet with a proscenium arch 20 feet by 26 feet and a large fly space about which more will be said below. Beneath the stage were six dressing rooms and a larger room for chorus or orchestra.

8 The horseshoe style gallery seated about 250-300 patrons. Behind the gallery were two large rooms for refreshments, a cloakroom, and access to a covered, open-air balcony over the main entrance to be "utilized by the band before the doors open, or by those who desire to have a sniff of fresh air between acts" (Columbian, 7 November 1898: 4). Above the gallery was the balcony or, as it was commonly referred to, "the gods," which seated about another 150-200 patrons on the lower end of the social scale.

9 Although the exterior of the Westminster Opera House was unattractive, the interior was lavishly decorated (Columbian, 8 March 1899: 1) and, functionally, the theatre compared very favourably with others in the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere (see Table 1). Of particular interest is the height from the stage to the rigging loft which was significantly greater than all the other theatres cited in the table. It was this feature especially that the promoters believed would be the key to the theatre’s success. As mentioned above, Herring’s Opera House had its limitations. The production of Faust by the Griffiths Company, for example, had played in New Westminster before but without the elaborate scenery. It would now be enjoyed in all its splendour in the new theatre in May 1899 (Columbian, 25 March 1899: 4). On another occasion in the Columbian, the writer clearly delighted in the opportunity for a bit of one-upmanship: "Miss Melville brings her own scenery, and it is worth mentioning that owing to the height of the wings in the New Westminster opera house, she is able to use several pieces here which cannot be used in Vancouver" (23 November 1904: 3).

Table 1 – Statistics of Selected Theatres compiled from Julius Cahn’s Official Theatrical Guide, 1900-1901, Vol. 5

Display large image of Table 1

10 In the absence of any surviving seating plans, box office receipts, or other financial records, it is not possible to determine with any certainty how the variously priced seats were allocated throughout the house. However, for a local amateur production in November 1902, there was apparently some misunderstanding about the price of seats and a clarification was published on the day of the performance: "Orchestra stalls, rows 1 and 2,50¢; rows 4, 5, 6 and 7, 75¢; rows 8 and 9, $1; balance of rows, 50¢; balcony, first row, $1; balance, 75¢; Admission, not reserved, 50¢ and 25¢" (Columbian, 26 November 1902: 4). It might very well be that this distribution of ticket prices applied only to this particular event, but it may also reflect the usual seating arrangements.

11 On opening night the standing-room audience enjoyed a performance of Gilbert and Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore by Vancouver’s Lyric, Operatic and Dramatic Company. One cannot help but wonder why Vancouver performers would be opening New Westminster’s new symbol of cultural progress. In the 1890s New Westminster did have a highly successful musical theatre society of its own and "provided the finest amateur opera entertainment on the mainland" (Evans 171). However, the society appears to have been inactive in 1898-1899—no doubt a casualty of the Great Fire—for there are no references to rehearsals or impending performances in the newspaper. The Vancouver Lyric, Operatic, and Dramatic Society was active and, with a performance of H.M.S. Pinafore, a perennial crowd-pleaser, theatre-goers were virtually guaranteed to have a memorable first experience in their new venue.

12 A packed house was thrilled by over 100 performers and a twenty-six-piece orchestra:When the curtain rose, there was a burst of applause, as the familiar quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore was discovered [...]. The tableau was splendid [...] and from the opening to the close, the singing and acting was excellent, and everything passed along smoothly. (Columbian, 9 March 1899: 1)The citizens had good reason to suppose that the Royal City had at last acquired a "comfortable and commodious place of public amusement" that would accommodate the best companies and keep entertainment dollars from being spent elsewhere. Some months later, upon completing his performances in January 1900, the actor Frederick Warde is reported to have said: "In no city the size of New Westminster which I have ever visited on the continent of America, have I seen such good hotel accommodations, or played in such a neat and artistically arranged Opera House" (Columbian, 22 January 1900: 4).

13 During the first season, theatre-goers were not wanting for quantity and variety of entertainment typical of the period. From opening night to the end of the first full season (June 1900), the Opera House brought in eighty-six events, amateur and professional, consisting of dramas, comedies, vaudeville shows, minstrel shows, spectacular extravaganzas, moving pictures, operettas, and an opera (Verdi’s Il Trovatore on April 30). With respect to range and number of events, this compares favourably with the 1899 season at the Vancouver Opera House (Todd, "Organization" 9). Each event was well advertised in the local newspaper and short announcements, sometimes including preview columns and photos of scenes or the lead actors.

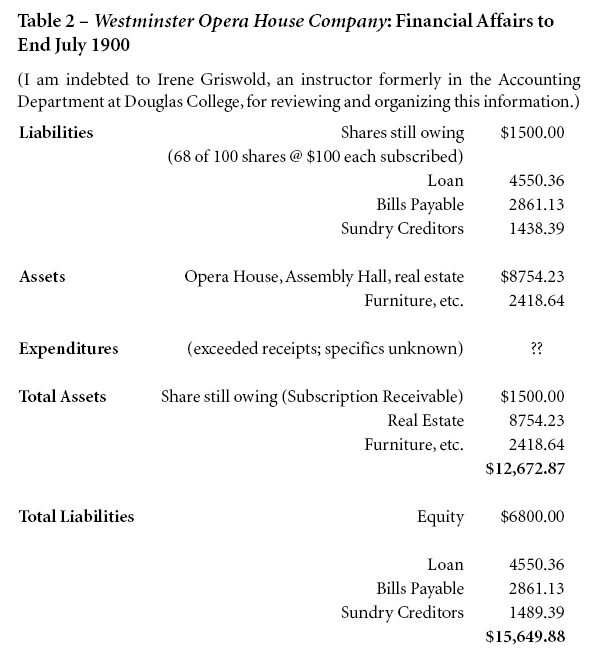

Table 2 – Westminster Opera House Company: Financial Affairs to End July 1900

Display large image of Table 2

14 On 5 September 1900 the Westminster Opera House Company held its second Annual General Meeting. The election of officers and financial affairs were summarized in the Columbian. Given that specific records of expenditures and receipts have not survived, it is not possible to determine accurately the Company’s financial situation. Based on the reported summary, it is possible, however, to estimate that the Company lost approximately $3000.00 in its first year of operation (see Table 2). For almost any business, a loss in at least the first year is anticipated. But shareholders must have been particularly concerned about the very low figure for box office receipts which, after more than a year of operation,apparently amounted to just under $1750.

15 In spite of the Opera House’s bigger and better surroundings, the new theatre had failed to attract sufficient audience support within a few months of its opening. Already on 10 June 1899 an editorial admonished the public for its poor show of support for the dramas and comedies of the Lyceum Company (Columbian,10 June 1899: 2). Less than a week later, it was reported that the audience for a concert had been a "little over a baker’s dozen" (Columbian, 15 June 1899: 1). Early in the Fall of 1899, Herbert L. Flint—he and his wife ran a show featuring hypnotism and spectacular effects—expressed "regret that the house [attendance] had not been sufficiently large here to encourage Mrs. Flint to display her magnificent robes with calcium light effects, as is the usual custom" (Columbian, 28 October 1899: 4). The Flints did not complete their engagement, cancelled the last show and headed for Whatcom County in Washington State. The management remained optimistic that the attendance problem would be resolved in the near future: "[. . .] from now on there will be less trouble in financing the affair especially if the citizens extend that measure of patronage which such a creditable house is entitled to respect" (Columbian, 5 September 1900: 4).

16 In the years immediately following the second Annual General Meeting, attendance problems continued to plague the Westminster Opera House. On 28 March 1901, in a notice about the evening’s attraction, the newspaper excoriated the public for its poor patronage.For some months past, the local Opera House Company have been striving to give its patrons a good class of attractions. That they have succeeded is admitted by those who have patronized them, but, unfortunately, the extent of the public patronage has been disappointingly limited [. . .]. In the meantime the small audiences which have greeted good companies of late, is making it more and more difficult to secure dates, as the reputation the town is gaining will make agents wary of booking New Westminster for next season. It is hoped, therefore, that for various good reasons, there will be a bumper house tonight. (Columbian, 28 March 1901: 4)In some instances, performers would play the city only if a minimum number of subscription tickets had been sold prior to the first performance (Columbian, 21 June 1901: 4). Not all the shows were poorly attended of course. On one occasion it was reported that 500 people were in the audience, "a large audience for New Westminster" (Columbian, 6 January 1904: 4).

17 After the second Annual General Meeting, there is no further accounting, summary or otherwise, to be found in the newspapers or elsewhere. However, poor attendance and financial difficulties continued. In November 1901 the License Inspector reported to City Council that he had been unable to collect the Company’s license fee and that "the company is in rather deep water" (Columbian, 14 November 1901: 1). Throughout the remainder of the 1901/02 season and the 1902/03 season the newspapers are silent concerning financial difficulties but it is safe to assume that the situation had not improved.

18 In October 1903, the manager, E.O. Malins, resigned, likely in view of the attendance and financial problems. Shortly after the new lessee and manager, A.R. Watts, took over, things apparently came to a head. The house remained dark for most of February 1904, and, in early March, City Council decided to cut off water and electricity to the Opera House on account of a bill for $600 that had apparently been owing since the theatre’s construction. In a letter to the Editor of the Columbian, Watts roundly criticized City Council for favouritism and lack of support for arts organizations:It appears that the Council, while willing to let this amount outstand as long as the property was in the hands of a local company, now desire to collect it from the mortgagees, who are already out of pocket on their investment, and who, of course, knew nothing of this liability when they made the loan. (City Council Minutes, 7 March 1904; Columbian, 8 March 1904: 4)In the end, it was agreed that the owners of the Opera House would pay monthly instalments toward the claim and on 23 March 1904, "after a long period of darkness," the Opera House re-opened.

19 Watts’s letter also reveals that the Westminster Opera House Company had changed hands at least by late 1903 or early 1904 and this may have been a factor in Malins’s decision to quit. Moreover, the Company itself languished and did not meet its commitments to the Provincial Registrar of Companies for a number of years thereafter. According to documents in the BC Provincial Archives, in 1911 the Registrar of Joint-Stock Companies sent a letter to the five original shareholders, inquiring as to whether the Westminster Opera House Company was "still carrying on business or in operation." The Registrar had not received returns, notices, and the like for two years. One of the five original stockholders simply wrote on his letter "Out of business" and returned it. Another wrote a brief reply in which he stated that he could not remember whether the Company had gone into liquidation or whether the mortgage had been foreclosed but that it had been some years ago. It should be mentioned that, at this time also, the first vaudeville house opened in April 1903. As will be explained later, the rise of vaudeville and film was a major factor in the decline of live theatre.

20 The year 1905 brought major changes to theatrical life in the Pacific Northwest with the completion in the previous year of the Great Northern Railway from Seattle to New Westminster and Vancouver. This enabled the two cities to become part of the Northwest Theatrical Association, a variety-vaudeville circuit out of Seattle that controlled "over seventy first-class theatres in the principal cities of the West" (Kelly 144) and the Theatrical Syndicate, a touring system controlled from New York. For the Westminster Opera House the connection with these circuits was brought about by the appointment of a new manager, E.R. Ricketts. As explained by Robert B.Todd in his excellent article, Ricketts had been lessee and manager of the Vancouver Opera House since 1902 and had "helped guide it to the position of the premier theatre in the province as Victoria faded into second place" (Todd, "Ernest Ramsay" 18). In 1905 Ricketts was strengthening his association with John Cort who controlled the Northwest Theatrical Association. Moreover, Ricketts was to become manager of the Victoria Opera House in January 1906. Ricketts’s ties to Cort’s circuit and his position as manager of the opera houses in Victoria, Vancouver, and New Westminster, must have augured well for the Westminster Opera House owners.

21 For reasons unknown, Ricketts managed the Westminster Opera House for only one year. From 1906 to 1910, several new owners and managers, still operating under Cort’s circuit, took on the challenge of making theWestminster Opera House a successful venture. But even the connection with the Northwest Theatrical Circuit was apparently not enough to bring out the audiences. In February 1910, Cort put New Westminster theatre-goers on trial:I am sending Louis James in Shakespeare’s "Henry the Eighth" to New Westminster. It is one of the best shows traveling and Mr. James takes rank among the most talented actors on the stage today. If the people of New Westminster appreciate good shows, they will have an opportunity of showing it when Mr. James appears in their city. The size of the audience on that occasion will largely decide the class of shows that plays in New Westminster, thereafter. (Columbian, 1 February 1910: 1)

22 Given the history of poor audiences, it is somewhat surprising that plans for a new, larger opera house were announced early in the 1910/11 season. John Cort and the then manager of the Westminster Opera House, Harry Tidy, proposed a theatre that would cost $150,000 to construct, would seat 1700 people, and would book in all the same shows as the Vancouver Opera House (Columbian, 12 October 1910: 5). The projected completion date was August 1911. In the meantime, the showing of films in the Opera House in an effort to draw audiences met with negligible success. After two weeks the manager was considering closing out the films (Columbian,12 September 1910: 1), but they did continue in the following years.

23 Perhaps Tidy and Cort believed that a more luxurious venue would build audiences, but the proposed new theatre never materialized and the newspapers are silent on the matter. It is likely that the promoters had trouble raising the necessary capital. In 1910, John Cort broke off his agreement with the Northwest Theatrical Association and, without his representation, investors may have been nervous about becoming involved in such an expensive venture. The Westminster Opera House did, however, maintain its relationship with the Northwest Theatrical Association, and the two organizations undertook to renovate the existing theatre at a cost much lower than that of constructing a new one. Building permit records in the New Westminster City Planning Department indicate that a permit (no. 341) was issued on 19 September 1911 in the amount of $6000 to alter the building and, on 29 November 1911, the newspaper described the extensive and radical improvements (Columbian 2). The renovations were carried out under the direction of E.W. Houghton, the official architect for the Northwest Theatrical Association and included a new entrance on Victoria Street, a large vestibule, a single gallery to replace the old double gallery, updated curtains (fire curtains and others) and other decorations, and a substantially enlarged stage capacity of 66 feet (the full width of the lot) with an opening of 30 feet. In addition, there were significant improvements to the acoustics, allowance for better viewing from all seats in the house, and updated fire and safety measures. The Westminster Opera House had a new lease on life and, once again, there were high hopes for success:Taken all in all, New Westminster has an opera house that is one of the best of its kind on the Pacific coast, and reflects great credit on the men who spent $10,000 to remodel the structure [. . .]. It is now up to the public to show that they appreciate what has been done to provide them with entertainment during the winter months. (Columbian, 20 December 1911: 2)

24 The remodeled theatre and continued efforts to show films, sometimes mixed with vaudeville, throughout 1912 and the early part of 1913 did not produce the desired results. On 26 August 1913 (Columbian 2) the owners of the Opera House threatened to close it down and, in September, made good on its threat (Columbian, 6 September 1913: 5). Within two months, a new lessee took on the Opera House for a period of one year and an option for a second.

25 For the next five years, the Opera House struggled on, continuing to offer up comedies and dramas by traveling companies or local groups, sundry musical concerts, public meetings, political speeches, and other events. The New Westminster Operatic Society, which had started up in 1913, became one of the major local users. During the war years,military band concerts and patriotic concerts formed important additions to the Opera House offerings. By the end of 1917, however, the viability of the Opera House had reached another crisis point and in January 1918 the citizens were given yet another opportunity to demonstrate their support for the old theatre. As part of a concerted effort to bring more industry to New Westminster, the Board of Trade established a "special committee on amusements" (Minutes, 22 January 1918). In conjunction with Frank Kerr, the current manager of the Opera House, the Committee delivered a familiar ultimatum to the public: "[. . .] to patronize this attraction [The Brat, a high-class play from New York], unless they want the opera house to remain closed and New Westminster to be put down as a dead town theatrically" (Columbian, 30 January 1918: 1). Although The Brat was well attended, performances of subsequent shows did not fare so well. The month of May was taken up mainly with a production of Merrie England by the New Westminster Operatic Society and no events appear to have held the boards in June. In the Fall of 1918, after a couple of public meetings in September, a planned National Service Concert for 25 October was never held owing to the Spanish Influenza epidemic which forced the closure of all public meeting places from about mid-October to mid-November.

26 The post-war years 1919-20 were years of tremendous energy and rebuilding but the Opera House seemed to reap little of the benefits. During 1919 the House remained dark; even local arts groups turned to other venues including the Duke of Connaught High School and the newly renovated and enlarged Edison Theatre—originally a vaudeville-film theatre that had been enlarged to accommodate live theatre productions in addition to its other offerings. With the Opera House unused for the year, it is no surprise to read on 8 December 1919 that a film company wanted to buy the Opera House and burn it down during the making of a film, as the building was "probably past its usefulness" (Columbian 1).

27 The offer of the film company apparently came to nothing and, in January 1920, it was announced that the New Westminster Operatic Society was taking over the Opera House (Columbian, 22 January 1920: 7). Although the Society had been staging productions in the Edison, The Serenade, Victor Herbert’s popular musical planned for April, required larger facilities. Some changes were made to the balcony seating in the Opera House and the heating apparatus was upgraded (Columbian, 27 February 1920:7). In addition to its own production, the Operatic Society brought in a play by the University of BC Players (11 March), a play by a Vancouver group of war veterans (3 April), and a Shakespeare play by the local high school (8 and 9 April). The Society’s production of The Serenade opened on 14 April and ran for three nights.

28 No other performances were advertised in May or June but the Operatic Society secured a lease for another year. By the Spring of 1921, however, the number of offerings dwindled. Although there would be one more attempt to resuscitate the theatre, as it turned out, the New Westminster Operatic Society’s production of Pepita, an operetta by Charles Lecocq, in April 1921 was the last event in the Westminster Opera House.

29 From May 1921 the Westminster Opera House sat silent, becoming increasingly dilapidated— "dilap, silent, May 1924" was added to the 1919 city fire insurance map—until it was finally demolished in June 1926. The story of its last years is a lengthy and fascinating one but has more to do with politics than theatre. Suffice to say that the Opera House became a pawn in a bitter power struggle between the City Council and the Provincial Fire Marshall, making front page news and becoming a test case in municipal-provincial relations.

30 The laments and complaints reviewed in the foregoing narrative reveal that from its earliest months the Westminster Opera House struggled with the problem of poor attendance and failed to live up to its cultural and economic promise. The theatre itself, although not nearly as luxurious as its Vancouver counterpart, was technically at least equal to the other theatres in the Pacific Northwest and capable of supporting the finest and grandest entertainment. Moreover, bookings reflect the efforts of managers to ensure that a broad variety and quantity of entertainment was put on the boards. However, even as the city gained access to the New York-based Theatrical Syndicate and the Seattle-based Northwest Theatrical Circuit under the leading theatrical managers (Ricketts and Cort) of the time, the Opera House was still unable to attract audiences in sufficient numbers on a regular basis.

31 It is possible that, at times, downturns in the local economy may have had some effect on theatre attendance but, overall, evidence suggests otherwise. During the 1890s the reputation the Pacific Northwest had gained for dismal audience attendance—an "unrewarding, if not deadly, circuit" (Evans 149)—likely owed a great deal to the economic depression. But by 1901 New Westminster showed "a marked increase in many lines of industry and business," and by 1903 it prospered as a lumber port and as the centre of the salmon canning industry (Gresko and Howard 41). In general the Royal City shared in Vancouver’s boom between c.1900 and the beginning of the First World War (Gresko and Howard 43).

32 Two factors appear to have been the major causes of the Opera House’s failure: the changing entertainment environment and, especially, the Royal City’s proximity to Vancouver. Even as the Opera House was opening its doors, vaudeville and film were becoming increasingly popular throughout North America. The first vaudeville-film theatre opened in New Westminster in April 1903 and, thereafter, usually two such theatres were in operation at any given time. Apart from the shows themselves, the much lower price of admission—10¢ in contrast to the cheapest seat at the Opera House of 25¢—made it increasingly difficult for the legitimate theatre to compete with the cheaper establishments. By 1910 or shortly thereafter, film especially was imperilling live theatre and driving theatrical companies out of business (Dizikes 280; Todd, "Ricketts" 22). As has been explained, the Westminster Opera House attempted, not very successfully, to show films as part of its offerings in 1910 and the years following, and remodelled the theatre in 1911. The same scenario is to be seen in Vancouver. In 1909 the Canadian Pacific Railway sold its Opera House to private investors. By 1913 it had changed hands again, was remodelled, and opened as a vaudeville theatre (Todd, "Organization" 17).

33 While all theatres in the Pacific Northwest may have lost audiences to vaudeville and film, the situation at the Westminster Opera House was also affected significantly by political and geographical circumstances. As mentioned in the opening pages of this article, New Westminster has been characterized as a "disappointed metropolis." The first blow to New Westminster came in 1868 when the capital of the province was moved from New Westminster to Victoria. The Royal City suffered an even greater disappointment when, in the late 1880s, Vancouver was chosen as the western terminus for the trans-continental railway. Although New Westminster was to enjoy considerable success as a centre for maritime trade and transport, it was the railway that would ultimately transform growth and development on the West coast. A third opportunity for New Westminster was lost when Vancouver was chosen as the site for the first provincial university.

34 Within about a decade after Vancouver’s incorporation in 1886, that city became the thriving centre of British Columbia’s new economy (McDonald 369). According to the 1901 Census, its population (27,010) was almost four times that of New Westminster (6499). By 1911, although New Westminster’s population had almost doubled to 13,199, Vancouver’s had almost quadrupled to 100,401 (Barman 390, Table 17). By the second decade of the twentieth century the Royal City seemed, to at least one visitor, to have all the appearances of royalty fallen on hard times (Bell 117) and by the early 1920s New Westminster had gained a reputation as the "penitentiary and asylum town" (Columbian, 31 January 1923: 12), a reputation that persisted well into the present author’s lifetime (Hamilton 5).

35 When the citizens of New Westminster planned their Opera House in 1899, coming out of an economic depression and rebuilding after the Great Fire, their optimism and expectations for the future of the city and its new cultural enterprise are understandable. They could hardly have seen the coming changes in the entertainment environment and the enormous growth of Vancouver. In 1910, as yet another new manager was about to try his hand at making "good money out of the business" of the Westminster Opera House, he conceded: "New Westminster, it is pointed out,is not by any means an ideal show town. It seems to be too close to Vancouver for that" (Columbian, 12 September 1910: 1). New Westminster residents were likely drawn by the greater variety of cultural enticements in the younger vibrant city then as they continued to be throughout most of the century.

36 A fairly recent occurrence is instructive in this regard. A very successful concert series, Music in the Morning, was established in 1984 in Vancouver, created in large part for elderly citizens for whom evening concerts were unmanageable. The founder of the series, June Goldsmith, a resident of Vancouver but a native New Westminsterite, duplicated the series in 1987 in the Royal City, convinced that patrons would welcome the convenience of being able to enjoy the concerts in their own town. After three years, Goldsmith was forced to abandon the project. Apparently her patrons in New Westminster saw the Music in the Morning concerts as opportunities for day-long outings to Vancouver.

37 In the absence of sufficient research into other opera houses in the Pacific Northwest, it is not possible to determine to what extent attendance problems were unique to New Westminster. It is certainly true that the rise of vaudeville and film affected entertainment venues everywhere. But in terms of regional development, the growth of urban centres in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, the experience of New Westminster was unique owing to its proximity to Vancouver. Notwithstanding its importance and success as a port between the Fraser River and the Pacific Ocean, from almost its earliest years the Royal City struggled to acquire those institutions that would define its profile and assure its growth as the leading urban centre in the Lower Mainland. As a marker of success in terms of economic and cultural growth, the Westminster Opera House essentially failed to meet its expectations and must be counted amongst the Royal City’s disappointments.

Works Cited

Barman, Jean. The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia. Toronto: UTP, 1991.

Bell, Archie. "The Royal City." Sunset Canada: British Columbia and Beyond. Boston: Page, 1918.

Benson, Eugene, and L.W. Conolly, eds. The Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1989.

Booth, Michael R. "Pioneer Entertainment." Canadian Literature 4 (Spring 1960): 52-58.

— . "Theatrical Boom in the Kootenays." The Beaver 292 (Autumn 1961): 42-46.

Columbian Newspaper (Daily Columbian, 31 July 1886 to 22 May 1900; Columbian, 23 May 1900 to 30 December 1905 and 2 January 1906 to 23 July 1910; and British Columbian, 25 July 1910 to 21 September 1963).

Conolly, L.W. "The Scholar and the Theatre." Journal of Canadian Studies 35.3 (2000): 150-61.

Dizikes, John. Opera in America: A Cultural History. New Haven:Yale UP, 1993.

Elliott, Craig. "Annals of the Legitimate Theatre in Victoria, Canada from the Beginning to 1900." Dissertation, University of Washington, 1969.

Elliott, E.C. A History of Variety-Vaudeville in Seattle from the Beginning to 1914. Seattle: U of Washington P, 1944.

Evans, Chad. Frontier Theatre. Victoria: Sono Nis, 1983.

Fenwick, Ian. "A Rich and Varied Theatre Tradition." Chilliwack Museum & Historical Society Newsletter (November 1988): 4-5.

Fraser, Kathleen D. J. "Theatre Management in the Nineteenth Century: Eugene A. McDowell in Canada 1874-1891." Theatre History in Canada 1 (Spring 1980): 39-54.

— . "London’s Grand:An Opera House on the Michigan-Ohio-Canadian Circuit 1881-1914." Theatre History in Canada 9 (Fall 1988): 129-146.

Fulks, Wayne. "Albert Tavernier and the Guelph Royal Opera House." Theatre History in Canada 4 (Spring 1983): 41-56.

Garret, R. M. and A. Rogatnick. "Reconstruction of a Gold Rush Era Opera House in the Yukon." Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Journal 28 (April 1962): 63-66.

Goffin, Jeffrey. "‘Canada’s Finest Theatre’: The Sherman Grand." Theatre History in Canada 8 (Fall 1987): 193-203.

Gooch, Bryan N.S. "New Westminster." Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. 2nd ed. Ed. Helmut Kallman and Gilles Potvin. Toronto: UTP, 1992.

Gresko, Jacqueline, and Richard Howard, eds. Fraser Port: Freightway to the Pacific. Victoria: Sono Nis, 1986.

Hamilton, Marianne and Mark. "The new New West: suddenly the Royal City, forgotten for a century is on the move." Beautiful British Columbia 32 (Fall 1990): 5-15.

Julius Cahn’s Official Theatrical Guide, 1900-1901. Vol. 5. New York: Empire Theatre Building, 1900.

Kallman, Helmut. "Concert Halls and Opera Houses." Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. 2nd ed. Ed. Helmut Kallman and Gilles Potvin. Toronto: UTP, 1992.

Kelly, Jessica H. "John Cort: The Froham of the West." The Coast 13 (March 1907): 144-47.

Map and Information of New Westminster City and District. New Westminster: Columbian Print, 1889. Provincial Archives, NWp 971.1N M297

McDonald, Robert A.J. "Victoria,Vancouver, and the Economic Development of British Columbia, 1886-1914." British Columbia: Historical Readings. Ed. W. Peter Ward and Robert A.J. McDonald. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1981. 369-95.

McIntosh, Dale. History of Music in British Columbia, 1850-1950. Victoria: Sono Nis, 1989.

McPherson, James B., and Helmut Kallman. "Opera Performance." Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. 2nd ed. Ed. Helmut Kallman and Gilles Potvin. Toronto: UTP, 1992.

Miller, Archie. "We were a two-opera town." Royal City Record/New Westminster Now Sunday 29 April 1990: 6.

— . "Remembering the opera house." Royal City Record/New Westminster Now Sunday 12 April 1992: 12.

— . "The show did go on, despite bleeding actor." Royal City Record/New Westminster Now Sunday 16 January 1994: 10.

Miller, Orlo. "Old Opera Houses of Western Ontario." Opera Canada 5 (May 1964): 7-8.

New Westminster Board of Trade Minutes. 22 January 1918.

New Westminster City Planning Department Records. Permit 341, 19 September 1911.

New Westminster City Fire Insurance Map. Toronto: Chas. E. Goad Co., 1907, rev. 1919. New Westminster Public Library. Uncatalogued.

O’Neill, Patrick B. "Saskatchewan’s Last Opera House: Hanley 1912-1982." Theatre History in Canada 3 (Fall 1982): 137-148.

Orrell, John. Fallen Empires: The Lost Theatres of Edmonton. Edmonton: NeWest, 1981.

Registrar of Joint-Stock Companies. Letter re company no. QE150. BC Provincial Archives, GR1438. Reel B4416.

Rittenhouse, Jonathan. "Building a Theatre: Sherbrooke and Its Opera House." Theatre History in Canada 11 (Spring 1990): 71-84.

Saddlemyer, Ann, ed. Early Stages: Theatre in Ontario 1800-1914. Ontario Historical Studies Series. Toronto: UTP, 1990.

Stuart, E. Ross. The History of the Prairie Theatre: The Development of Theatre in Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan 1833-1982. Toronto: Simon and Pierre, 1984.

Todd, Robert B. "Ernest Ramsay Ricketts and Theatre in Early Vancouver." Vancouver History 19 (February 1980): 14-23.

— . "British Columbia, Theatre in." The Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1989.

— . "The Organization of Professional Theatre in Vancouver, 1886-1914." B.C. Studies 44 (Winter 1979): 3-24.

Wolf, Jim. Royal City: A Photographic History of New Westminster 1858-1960. Surrey, BC: Heritage House, 2005.

Notes