Articles

Fusing the Nuclear Community:

Intercultural Memory, Hiroshima 1945 and the Chronotopic Dramaturgy of Marie Clements’s Burning Vision1

Robin C. WhittakerUniversity of Toronto

Abstract

In recent years, attention to Marie Clements’s work as a playwright has gradually accumulated. Her plays are eagerly produced across Canada and around the world. Scholarly articles have appeared on these pages, as well as in Canadian Theatre Review, Theatre Research International, and the Baylor Journal of Theatre and Performance, and panel papers focusing on her work have been presented at conferences from Vancouver to Belgium. Much of this attention has dealt with three mutually definitive aspects of her plays: their autobiographical relevance to Clements’s life and worldview, their aboriginality, and their staging of women. That is to say, for the most part attention to Clements’s work has been predicated on questions of identity that flow from the "personal engagement with the text by its writer-actor" (Gilbert, "Shine" 25). Here I consider her award-winning play Burning Vision as performing cultures in ways that are productively political, imaginative, theatrical, and complex. I argue that moments of reciprocal communication between cultures—"intercultural handshakes"— are negotiated by Clements as "timespace" moments through a Dene-inspired form of "chronotopic dramaturgy" which, following Mikhail Bakhtin and Ric Knowles, re-visions the ways in which time and space structure a theatrical work and inform our understanding of the political effects at play.Résumé

Ces dernières années, on s’intéresse de plus en plus à l’œuvre théâtrale de Marie Clements. Un peu partout au Canada et à travers le monde, on s’empresse de monter ses pièces. Des articles sur l’œuvre de Clements sont déjà parus dans notre revue, de même que dans Canadian Theatre Review, Theatre Research International et le Baylor Journal of Theatre and Performance; des plénières sur l’œuvre de Clements ont eu lieu dans le cadre de colloques tenus de Vancouver jusqu’en Belgique. Or, une bonne part de l’attention consacrée à la dramaturge a porté sur trois aspects reconnus des pièces de Clements : le rapport autobiographique de ces pièces à la vie de Clements et au regard qu’elle jette sur le monde, le caractère autochtone des pièces et la mise en scène des femmes. L’attention portée à l’œuvre de Clements a donc été largement fondée sur des questions d’identité qui découlent de « l’engagement personnel de l’auteure-actrice Clements à l’endroit du texte » (Gilbert « Shine » 25). Ici, Whittaker examine la pièce Burning Vision pour laquelle Clements a remporté plusieurs prix en montrant qu’elle offre des représentations culturelles qui sont politiquement productives, imaginatives, théâtrales et complexes. Il fait valoir que Clements présente les moments de communication réciproque entre cultures—des « poignées de main interculturelles »—comme des moments d’« espace-temps » inspirés d une forme de « dramaturgie chronotope » dénée qui, comme l’ont déjà montré Mikhail Bakhtin et Ric Knowles, redéfinissent la façon dont le temps et l’espace structurent une œuvre théâtrale et informent notre conception des effets politiques en jeu.~

1 There is a moment in Burning Vision in which the Dene See-er, living as he does on the east side of Sahtú (now Port Radium on Great Bear Lake) in the Northwest Territories in the late 1880s, speaks the following words from offstage:Can you read the air? The face of the water? Can you look through time and see the future? Can you hear through the walls of the world? Maybe we are all talking at the same time because we are answering each other over time and space. Like a wave that washes over everything and doesn’t care how long it takes to get there because it always ends up on the same shore. (75)It is a moment in which the See-er proposes a collective act of divination in the midst of critiquing his own divination. He at once gestures toward his power, which is his raison d’être in his community and in the play, while asking whether "we" possess this same power. He positions himself above us, around us, on the air, but at the same time includes us in his see-ing, our see-ing. We are linked, as he says, over time and space; intercultural communication transcends the borderland walls that separate us. "We" or "us," as John Whittier Treat says, are the victims and the potential victimizers (250). We necessarily answer each other, everywhere and forever.

2 Clements uses the event of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, and the fact that the uranium used in that bomb was mined by Dene miners from Dene land, to suggest spiritual, political, and ethical synchronicity at three geographically and culturally distant locations: Hiroshima, Japan; New Mexico, United States; and Port Radium in the Northwest Territories, Canada. The play operates by way of premise more than plot, staging moments in world history that fall roughly between the late 1880s and the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima to argue for their connection over time. The activities and voices of over twenty characters are arranged and recombined fluidly through four "Movements," presenting narrative connections by juxtaposition. Clements’s adroit appropriation of a nineteenth-century Dene See-er’s prophecy reframes the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Insomuch as the two events are separated by sixty years, the play reevaluates notions of historical and cultural responsibility across times and spaces. By re-implicating otherwise incongruent cultures in the shared event of the bombing, Clements refocuses the lenses of received history and the ways in which histories are (re)constructed while emphatically reminding us that the atomic bomb, and the uranium that it contained, continues to test "the walls of the world" today.

3 As a work of fiction that draws from known historical events, the play works across cultural communities by evoking the possibilities of cultural memory. Clements’s revision of the war-ending event triggers jarring chronological fissions, as if dramatic time and space are themselves made victims of the bombing. This effectively shifts the burden of received meaning from specific, culturally tethered historical events to spatially and temporally untethered symbolic characters (some fictional and some historical) as they coast through locations and moments. The play’s chronotopic dramaturgy replaces the neo-Aristotelian unities of Time and Place as a structuring strategy to question received politico-historical knowledge: its specifically delineated spaces are allowed to fluidly and dialogically converse. The play unfolds issues of ethnic, geographical, and nationalist inclusion in the traditionally exclusive histories of Euro-North American, Japanese, and Dene peoples. After comparing a selection of post-war historicizations of the Hiroshima bombing, I want to show that Burning Vision’s "chronotopic dramaturgy" reclaims one indigenous temporal and spatial logic, that of Dene peoples, displaced by European linear timekeeping and mapping systems during acts of colonization. I then want to categorize the types of characters that Clements employs and argue that they stage collective, intercultural memories that work against received Western historicizations of Hiroshima to form a matrix of dialogic conversations. Finally, I examine two ways in which the play stages the colonial trope of "discovery." Throughout, I draw together Native American applications of Mikhail Bakhtin’s chronotope in literature with Ric Knowles’s formulation of an alternative dramaturgy of space and time in order to propose that Burning Vision constructs a form of dramaturgy that can be called "chronotopic." In doing so I bring to bear both Dene-specific and non-aboriginal theoretical frameworks in order to mirror what I believe is an intrinsic element of Clements’s writing: her polyvocal, intercultural voice at the interrelated levels of dramaturgy and ideology.2

Mapping Cultural Memory: Histories Compared

4 In the opening to his keynote address at UC Santa Cruz on the day after Veterans (Remembrance) Day 1999, historiographer Hayden White posed the following question:How are historical pasts constructed? That historical pasts have to be constructed seems self-evident. To be sure, historians speak of their work as reconstruction rather than construction. For historians the past pre-exists any representation of it, even if this past can be accessed only by way of its shattered and fragmentary remains.

5 White went on to acknowledge that "destruction" always accompanies "construction" when reconstructing the past and that professional ethics guide choices made by historians in their "responsibility to their predecessors." Western historians have dealt with the fabulae of history in ways that extend into Western ways of thinking generally about past events.

6 For example, Western histories look at the moment at which the first wartime atomic bomb was dropped, often emphasizing that the "story" is ingrained in Western memory. American historian Michael J. Hogan writes in 1996:The story is a familiar one, though nonetheless dramatic. In the early morning of 6 August 1945, an American B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, lifted off a runway on Tinian Island in the Pacific. Piloted by Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, who had named the giant Superfortress after his mother, the Enola Gay carried a ten-thousand pound atomic bomb known as "Little Boy." At 8:15 A.M., the crew of the Enola Gay covered their eyes with dark glasses and the bombardier, Thomas Ferebee, released the huge orange and black bomb over Hiroshima, Japan, a city of 250,000 people, many of whom were starting their last day on earth. The bomb exploded over the city with a brilliant flash of purple light, followed by a deafening blast and a powerful shock wave that heated the air as it expanded. A searing fireball eventually enveloped the area around ground zero, temperatures rose to approximate those on the surface of the sun, and a giant mushroom cloud roiled up from the city like an angry gray ghost. Within seconds Hiroshima was destroyed and half of its population was dead or dying. Three days later, a second atomic bomb destroyed the Japanese city of Nagasaki, killing more than 60,000 people. (1)For Hogan, the story is "familiar" and it is "dramatic." As with many Westernized stories, there is the dawning of a new day, a heroic departure, a personal connection in the naming of the ship (as a warrior might name his steed) and the naming of the weapon. There is the warrior donning his armour (the dark glasses) and a rhetorical flourish—indeed, a foreshadowing—with the enemy "starting their last day on earth." Colourful adjectives dot Hogan’s narrative. Heavenly objects transform the planet and an "angry gray ghost" evokes a flair for the gothic. Repetition, an important convention in Western dramatic structuring, condemns Nagasaki to a similar fate. Hogan westernizes the events as if they form an ordered heroic saga. Notably Hogan’s telling, as is common in North American histories, describes Hiroshima from the sky to the ground.

7 Japanese history has taken a different approach to remembering Hiroshima. For one, it remembers it from the ground up. An eyewitness account by Dr. Shuntaro Hida:The sky was clear blue. At an extraordinary height, a B-29 bomber came into view, shining silver in the light. It moved very slowly and appeared as if it had stopped in mid-air. It was approaching Hiroshima.[...] At that very moment a tremendous flash struck my face and a penetrating light entered my eyes. All of a sudden my face and arms were engulfed by an intense heat.[...] I expected to hear shouts of "Fire!" but I saw only blue sky between my fingers. The tips of the leaves on the porch had not moved an inch. It was extraordinarily quiet. "Might it only be a dream?" I thought.[...]I could see a long black cloud as it spread over the entire width of the city.[...] What I saw was the beginning of an enormous storm created by the blast as it gathered up the mud and sand of the city and rolled it into a huge wave. The delay of several seconds after the monumental flash and the heat-rays permitted me to observe, in its entirety, the black tidal wave as it approached us. Suddenly I saw the roof of the primary school below the farmer’s house easily stripped away by the cloud of dust. Before I could think about taking cover my whole body flew up in the air.[...] A moment later I could see the blue sky above me where the roof had been. (417)Hida’s description is no less dramatic. There is the sublime image of the "shining silver" bomber stalking the city like a lion over its prey. The attack is swift, "penetrating" and disorienting and with the mention of the blue sky and the leaves, the scene becomes beautiful and horrific, a sublime "dream." Then the "long black" storm cloud, like a "black tidal wave," moves toward Hida, as if nature itself had been made to menace the countryside. Buildings are hurled into the air, as is Hida, while the clear sky above him bears witness. But unlike Hogan, Hida does not comment on the fact of his own retelling. He does not encapsulate his own rendering as an always already or a packaged history. His is a firsthand account, a lived journey rendered in writing. These two accounts of a shared event represent a "familiar" Western historicization and a personal voice of a Japanese hibakusha (victim of the atomic bombings).

8 In contrast is the personal voice of Second World War American Navyman, Alvin Kernan:3The [atomic] bomb[s] gave [life] to me in my way of reckoning, and while others may feel otherwise, I was grateful and unashamed. In after years, on the faculty of liberal universities where it was an article of faith that dropping the bombs was a crime against mankind and another instance of American racism, I had to bite my tongue to keep silent, for to have said how grateful I was to the bomb would have marked me a fascist, the kind of fascist I had spent nearly five years fighting! (155, emphasis in original)Though implicated as an aggressor in battle, Kernan has ever since negotiated his awareness of the point of view of others with his own hard-fought convictions. His perspective, often quickly rejected in Western society today, may nevertheless be common among those who were directly involved in the war, whose values shaped, and were shaped by, their direct participation in it.

9 For the Dene, the Hiroshima bombing may have been far away, but a significant facet of their experience of it is that it is expressed in a tradition of oral history characterized by elements of magic. The uranium that had been used in the atomic bomb and that which had been used repeatedly at the New Mexico test site before the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been mined and moved by Dene miners at Port Radium in the Northwest Territories. Sixty years before the bombing of Hiroshima, and an ocean away, the See-er whose prophecy Clements dramatizes foresaw a moment of great destruction and change in the world. George Blondin, who voiced the Dene See-er in the play’s Vancouver premiere, prints a retelling of the See-er’s prophecy in his book When the World Was New:I watched them and finally saw what they were making with whatever they were digging out of the hole—it was something long, like a stick. I wanted to know what it was for—I saw what harm it would do when the big bird dropped this thing on people—they all died from this long stick, which burned everyone. The people they dropped this long thing on looked like us, like Dene. I wondered if this would happen on our land or if it would harm our people. But I saw no one harmed here, only the material that was taken out of our land by people who were just living among us. This bothered me. But it isn’t for now; it’s a long time in the future. It will come after we are all dead. (79)Blondin’s retelling of the prophecy makes a number of points clear. First, the prophecy appears to be remarkably accurate. The See-er articulates a skepticism that though the victims look like Dene, they may not be. The See-er can apparently see through visual similarities to posit a distinction between his people and the victims in his vision. Second, the language is that of nature. When words cannot name the objects he sees, words for nature stand in: the bomb is a "stick," the plane is a "bird." Third, his vision can "tell time." Not in precise increments but in proximity to his current time: "a long time in the future" and "after we are all dead."

10 The See-er’s prophecy holds dramaturgical authority in Burning Vision because it provides structure, as well as content, to the staged events. And because the question of authority shifts intercultural dialogue from balance to hierarchy, it deserves particular attention here. As June Helm records, the authority of a Dogrib Dene prophet’s judgment is dependant on the community acknowledging the prophet’s "authenticity" : "visions and messages must be deemed true" before the status of prophet is granted (Helm, Prophecy 52). The efficacy of each prophecy rests in its (moral) value to the community at the time, as opposed to its value to any individual (70). It is not prescriptive or dictatorial because its authority must be accepted by consensus. Clements situates the See-er’s prophecy as a structuring motif, yet positions the audience and readers as the community that grants (or does not grant) authority to the vision’s authenticity. That the See-er’s prophecy in Burning Vision is fulfilled sixty years after it is made augments Clements’s use of it as a device that shows "we are answering each other over [significant spans of] time and space." And as it is the immediate community that acknowledges (or not) the validity of the prophet’s revelation, Clements positions her audience so that it may accept (or not) the See-er’s vision well after both the nineteenth-century vision and the twentieth-century event. The Seeer’s subjectivity is far from Hogan’s distanced preface: "The story is a familiar one, though nonetheless dramatic" (1). It is as personal as Hida’s telling, but spatially and temporally it is far from the event itself, making no claims to precision yet never doubting its own validity as a vision. Dramaturgically, the See-er’s "burning vision" binds the play’s events, characters, settings, and premises together where time and space do not.

11 Testimonials such as those of the Japanese, Euro-American, and Dene participants in the Hiroshima bombing foreground the complexity of intercultural memory, even as they deal with a known and "familiar" event. In any telling, past events become referents organized into a temporally and spatially biased account. At the same time that these events form our bases of understanding the past and the present, they limit our capacity to envision hybridized, intercultural futures. It is by juxtaposition rather than displacement, or to use White’s term, "destruction," that hybridity lays fruitful ground for historiography. Acknowledged histories result from a comparison of vantage points, and synthesis is by no means trivial.

Chronotopic Dramaturgy and the Motif of Prophecy: Time, Space, Event

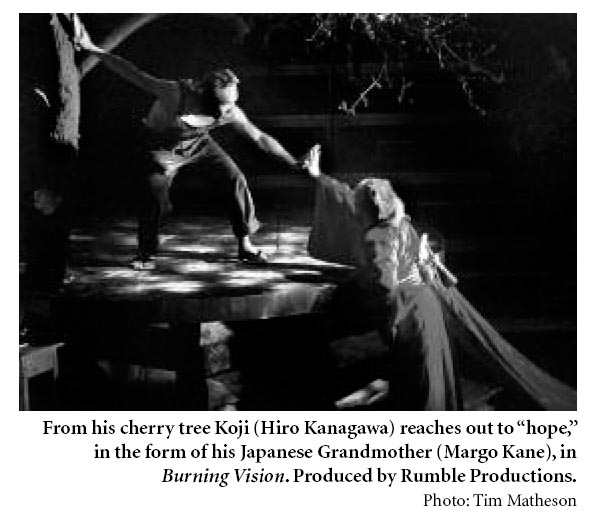

12 To gain insight into Clements’s use of time and space and the political effect of each, consider Mikhail Bakhtin’s rendering of the "chronotope" in literary genres, as reapplied to performance. Emerson and Holquist’s translation of The Dialogic Imagination defines the chronotope, which Bakhtin borrowed from Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, in an oft-cited passage asthe intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships that are artistically expressed in literature. [. . . ] Time, as it were, thickens, takes on flesh, becomes artistically visible; likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time, plot and history. This intersection of axes and fusion of indicators characterizes the artistic chronotope. (84)Yet Bakhtin famously eschewed drama as inferior to the novel.4 When he refers to drama, it seems that he refers only to a specific form of Aristotelian stage naturalism. His words on the function of time in drama are worth citing for their obvious contrast to Burning Vision’s dramaturgy:The time of ancient epic and drama was profoundly localized, absolutely inseparable from the concrete features of a characteristically Greek natural environment, and from the features of a "man-made environment," that is, of specifically Greek administrative units, cities and states. [. . . ] These classical Greek chronotopes are more or less the antipodes of the alien world as we find it in Greek Romances. (Dialogic 104, emphasis in original)Time in Burning Vision is far from "profoundly localized." Because the play shifts meaning from events that are tethered to specific times and places to characters that are untethered to linear time or naturalistically presented places, it breaks out of the "folk-mythological time" chronotope (104) to which Bakhtin relegates drama, that in which "historical time (with its specific constraints) begins to come into its own" (104).

13 Alan Velie argues that the "adventure-time" chronotope operates in ways akin to the machinations of the Native American trickster novel, which echoes aboriginal oral traditions: time is static, characters do not develop (or age) and an "extemporal hiatus" replaces the presumptive change associated with the movement of narrative time (123-24; c. f. Bakhtin, Dialogic 89-90). In Burning Vision we read time through the action of characters as we do in the adventure-time of aboriginal storytelling. This is performed by what Ric Knowles calls a dramaturgy in which "interrelations between objects, characters, events, and audiences do not occur in space and time but themselves create and define— constitute—‘space-time’" (225, emphasis in original). So-called "‘Newtonian’ concepts such as ‘the trajectory of a character’" (Krizanc quoted in Knowles 225) are replaced by "alternative structures" (Knowles 225) in which "character" bears time-space meaning primarily and internal, mimetic development secondarily. There is a sort of scripted magic here with which audiences and readers are encouraged to allow the normally divisive elements of time and space to fade behind an interest in fictional combinations of performance time and performance space, as if the performance were the cultural memory itself. This may be termed chronotopic dramaturgy, where times and spaces are wrested from their fixed and predictable dramaturgical functions and then recombined in packaged, defamiliarized timespaces which, ordered in successive episodes in scenes, constitute the form of the play. In chronotopic dramaturgy, adventure-time is grafted onto abstract characters in a fictive world in which the juxtaposition of events and perspectives offers the possibility of revision, in this case transcultural re-vision. With a wide aperture, which encompasses ethnogeographies beyond North America, the play applies the adventure-time chronotope to communities in an atomic age. Here, chronotopic dramaturgy enacts an explosive fission on our perception of a stabilized world. In Clements’s hands it is a scripted metaphor for the bombing itself.

14 The Dene prophecy motif, grounded in an oral storytelling structure, informs Clements’s chronotopic dramaturgy with political effect. In the world of Burning Vision we witness the effects of indigenous timekeeping systems displaced by linear time. Says the older Widow of her Dene past, "We used to be able to tell where we were by the seasons, the way the sun placed itself or didn’t, the migration patterns of the caribou. Time. [. . . ] By the way we dressed, or how we dressed, or undressed the ones we loved. Time" (44). The sounds of caribou herds float through the play as markers that time’s passing in an indigenous culture is of nature’s doing; time is not manmade. As Helen Gilbert and Joanne Tompkins note, "Aboriginal Dreaming [. . . ] posits the existence of a continual present which also includes past and future" (137). This is a notion that has no place in linear time formations and was displaced as a major mode of historicization on the North American continent at the time of contact. Conversely, though linear time need not constrain aboriginal dreaming, it was not an entirely foreign concept to certain early contact, oral tradition Dogrib Dene who "evince a firm comprehension of both historical actualities and their temporal succession. It seems evident," Helm explains, "that the sharp sense of ‘time’s arrow’ in this sector of Dogrib oral tradition is, in fact, based on the swiftly successive effects of the impinging European presence on Dogrib experience" (People 221). Helm thus offers the distinction between two sorts of time, both evident in Dogrib Dene oral traditions: pre-contact "Floating Time," which may be evident in stories that tell of events from "thousands of years ago" (for example, myths or stories that do not tell of a world similar to today’s); and the subsequent "Linear Time" of stories from proto- and early-contact time (221). As Burning Vision makes evident, it is not only "the times" that are "a-changin’," but the ways in which timekeeping technologies define change, as do the rehistoricizations and erasures of these technologies. It is the act of supplanting one timekeeping system for another that is a necessary act of colonization.

15 It is also necessary for the colonizer to supplant one space-mapping system for another. Burning Vision offers a "spatial logic," to use Gilbert and Tompkin’s term, "through which to interpret history/geography" ; "an interactive historical space that records the inscriptions of past and present simultaneously rather than sequentially" (147). If European settlers on the North American continent literally re-mapped the land to serve their own politico-administrative activities—from province to state to territory and so on—then Clements suggests that political borders need not limit the staging of human connections and their potential meanings (or rather their potential to mean). Even geographical distances are made obsolete, so that while a uranium Miner in 1930s Port Radium asks into the darkness, "Hello? Is anyone there?" , Clements has the test dummy Fat Man in 1945 New Mexico adjacently respond, "Who’s there?" (45). The geographies of precontact (and premapped) migratory Dene peoples had been determined not by the European cartographic agenda but by natural phenomena (and their changes), including fisheries, caribou passage routes, and climate factors (see Helm, Peoples 18). "Socioterritorial groupings" (18) are delineated not by lines drawn in ink, but by lines drawn in kinship and linguistic bonds. To stage the historico-spiritual connections made by the Dene See-er, Clements fuses the setting of the vision to that of the theatre. Her fictive characters are used to stage adjacent spiritual connections as reported by the See-er over the fluid, changeable space moulded by the play’s chronotopic dramaturgy.

16 In order to rehistoricize and remap received narratives, Clements’s chronotopic dramaturgy weaves events from received history with fictional characters and fictional relationships. Her selection of historical moments can be broken down into three categories. First are specific events—those events with fixed times and spaces from received history: the Bros. Labine find high grade pitch stake in 1930 near Port Radium (39), the US government tests the first atomic bomb 16 July 1945 near Trinity, New Mexico (39),5 the US government orders eight tons of uranium from the Canadian company at Port Radium in 1941 (65), and the first warfare atomic bomb is dropped 6 August 1945 on Hiroshima (118). These are staged events in the play, acting as signposts. They are recognized as events from received history with specific, mappable locations to which audience members may contextualize their encounters with the play. As chronotopic timespaces they represent directly the times and places they stage. They are examples of Gilbert and Tompkins’s "temporal signifiers" (142).

17 Second are general events—those events that we know occurred, but in the play are not linked to specific times and spaces: the Dene Ore Carriers having died from contact with uranium, the path of the ore’s transport and the landmarks by which it passed, North American women painting radium onto watch dials in the 1930s and later dying of radium contact poisoning, Lorne Greene’s CBC news broadcasts, Slavey (Dene) Announcers broadcasting on Northern radio their calls for missing loved-ones, and Tokyo Rose’s supposedly eroticized radio broadcasts to the US troops stationed in the Pacific. These events are not represented as specific time-space moments, and they do not generate specific reversals or recognitions. They function as transitional time-spaces between specific events.

18 Third is a specific event made general: the See-er’s vision during one night in the late-1880s on the east side of Sahtú. Though this event occurred in one time-space, in Clements’s play we can read the See-er’s vision in two ways. In one, his voice and his vision are spread throughout the course of the times and spaces represented in the play, in which case the play is spread over as many years as are represented in the dramatic action; in the other, his voice and his vision do indeed occur during the one night in the late 1880s at Sahtú, in which case Clements has conflated all of the represented times and spaces into the experience of one night. In the former reading, we are traveling through the play with the See-er as our guide as if experiencing history/his story in his future, our past. In the latter, our very evening of theatre or our reading of the play6 is our own, individual, "burning vision," analogous to that of the See-er’s vision a century ago. Thus, our act of viewing or reading the play today becomes our act of divination through which we may see our past and a future. To use Bakhtin’s terminology, our chronotope in life at the extended moment we apprehend the play fuses to the See-er’s chronotope in art. We are the See-er’s community. The play is a vision we experience.

Concrete and Abstract Characters Play Memory

19 As the previous comparison of a variety of histories of a single event reveals, there are challenges to synthesizing cultural memories. That is to say, cultural memories are difficult to render inter-cultural. For example, histories written by the victors may be limiting in that they represent the most politically strategic memory of an event—as Martin J. Sherwin cogently puts it, a memory of "their war" ("Memory" 344, emphasis in original). In place of monologic tellings, Clements offers a re-vision of histories in the form of "play" in which diverse experiences are allowed to coexist in dialogue. One history is never granted authority or privilege over another. Neither Japanese nor Japanese-American nor Euro-North American history is constructed as dominant, and Dene history structures the play only insomuch as the audience is complicit with the "vision." She invests each character with highly political time-space meaning. She then allows the characters to interact in order to bring these meanings together in dialogue. Characters rarely speak lines verbatim from historical records but experience a collective memory of the events. Each character embodies particular segments of this collective memory, temporally and spatially. Even the monologic, authoritative voice that claims to speak to and for a nation is not ignored, as when Clements uses the offstage voices of radio broadcasters to represent the official voice of various peoples. In the playing of these voices, the accumulated effect is a fictional, imaginative, transcultural dialogue manifest in the See-er’s words "answering each other over time and space" (75).

From his cherry tree Koji (Hiro Kanagawa) reaches out to "hope," in the form of his Japanese Grandmother (Margo Kane), in Burning Vision. Produced by Rumble Productions. Photo: Tim Matheson

Display large image of Figure 1

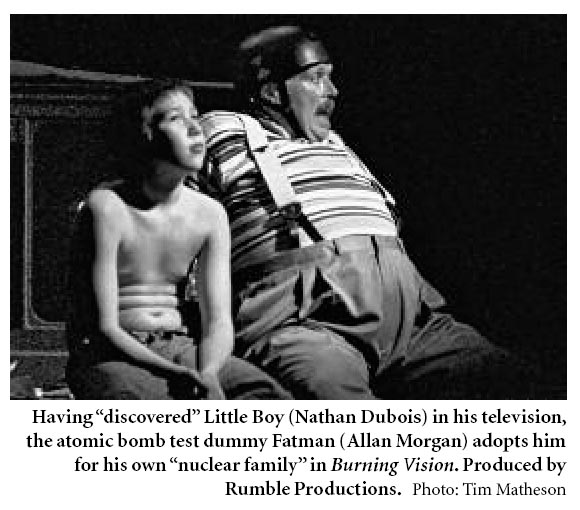

20 Clements’s characters are signifying indices of their particular cultural groups. I divide her characters into two categories: concrete characters and abstract characters. The concrete characters are those who are primarily human and secondarily symbolic. These include Round Rose, the Widow, Rose, Koji, the Radium Painter, Captain Mike and his Stevedores, the white Port Radium miner, and the Bros. Labine. For most of the play these characters are human, present on stage, and lead contiguously constructed lives. They change over time and react as humans to their spaces and the situations around them. They are mimetic. Conversely, the abstract characters possess visible or auditory human qualities, but they are primarily symbolic. These include the Dene See-er (in voice-over, omniscient, in the air and the airwaves), Little Boy ("the personification of the darkest uranium found at the centre of the earth" 13), Fat Man ("bomb test dummy"), the Japanese Grandmother ("hope"), the Dene Ore Carrier (deceased), and Lorne Greene, the Slavey DeneAnnouncers, and Tokyo Rose (on the airwaves, the latter of whom is voiced by Round Rose). Abstract characters do not change with or react to the times and spaces around them. They are anti-mimetic, spiritual and, in a sense, magic.

Round Rose (Julie Tamiko Manning) sits in Japan typing letters as "your true American daughter" Tokyo Rose, while Koji (Hiro Kanagawa) sits in his cherry tree: "I am nothing now and yet inside myself that no longer exists I am still Japanese." Time and space collide as identity experiences fission in Burning Vision. Produced by Rumble Productions. Photo: Tim Matheson

Display large image of Figure 2

21 Meaning is generated in the dialogic conversations between these characters. They are free to interact across times and places, effectively rehistoricizing and remapping the ways in which the dialogues of past events are mediated. Characters carry historical meaning with them. Through their interactions they constitute new time-spaces. Thus, when Koji—a fisherman near Hiroshima on 6 August 1945—meets Rose (91)—a Métis woman in Ft. Norman during the uranium mining years (55)—two groups of people who are victims of Euro-North American harvesting of A-bomb uranium are able to converse and ask one another, "If you make me yours do we make a world with no enemies?" (95); "If we make a world, we will make one where there are no enemies" (96). And Koji and Rose can therefore have a child who is cared for by a Dene Widow as if he were her grandson. (In this sense they are one of the play’s "nuclear families.") Historical memory "works through these figures" (Malkin 7, emphasis in original) as they "themselves create and define—constitute—‘space-time’" (Knowles 225, emphasis in original). Each character becomes a catalyst for the fusion of meanings in a free-form dialogue of received history that traditional notions of linear and mapped dramatic structure cannot accommodate.

22 Of these specific and general events, and of these concrete and abstract characters rendered in chronotopic dramaturgy, we may draw a number of conclusions. First, the accumulation of the characters’ dialogic interactions stands in for what Jeanette R. Malkin calls "a culturally determined collective subconscious" (8). Burning Vision proposes a polyvocal, transcultural memory in place of the North American linear/mapped memory of the victor. When fictional characters loaded with time-space meaning meet across their tagged times and places, they perform an act of renegotiation that is necessary when one wishes, as the back cover of the Talonbooks publication proclaims, to "unmask the great lies of the imperialist power-elite." By performing chronotopic dramaturgy in dialogic time-space, Clements invokes an intercultural worldview of exchange in which received historical events find new relevance, where the old ascribed meanings are renegotiated in an act of devaluing and reevaluating arbitrary, nationalist borders.

23 A second conclusion is that without linear time or mapped space to limit the meanings of received events, chronotopic drama-turgy denies closure. In this capacity, the traditional comic trope of marriage undergoes perversion. Marriage does not reconfirm the order of things here, as it does in traditional comic form. Instead, marriage serves to open up new combinations of discourse. Burning Vision’s newly-minted "nuclear families" —those of Fat Man, Round Rose, and Little Boy; Koji, Rose, Koji the Grandson, and the Widow; and of the Miner and the Radium Painter—offer a transcultural future— "tough like hope" (121) the Widow calls her grandson. The Widow’s call for a worldview change—as opposed to the traditional use of marriage as a call for the reclamation of the status quo—at once gestures to hope for her own family and hope in the marriage of the white man test dummy (victim and victimizer in one) and the Japanese-American radio voice (victim and so-called victimizer in one). Here, the marriage trope recombines characters’ embodied time-space meanings to produce hope for the future.

The Radium Painter (Erin Wells) walks into the Miner’s (Marcus Hondro’s) light in Burning Vision. By implying that the uranium he mined led to her radium poisoning years later, Clements revaluates notions of historical and cultural responsibility across times and spaces. By having them marry, Clements proposes reconciliation and hope. Produced by Rumble Productions. Photo: Tim Matheson

Display large image of Figure 3

24 This forward-looking sentiment echoes Peter Schwenger’s words whenhesays, lessoptimistically, "bynowitshouldbeapparentthatthe end of America’s Hiroshima is not to be attained;there will be no time when Hiroshima will have been over" (251). Where Schwenger warns that the disaster of Hiroshima will never find closure, Clements’s play suggests that this perpetual state might generate perpetual healing through transcultural dialogue over time and space.7

Performing Re-Visions as Re-Discoveries

25 An act of see-ing is an act of discovery. Following the bomb detonation sequence that opens Burning Vision, Little Boy says amid the white man’s audible "radio footsteps":Every child is scared of the dark, not because it is dark but because they know sooner, or later, they will be discovered. It is only a matter of time [. . . ] before someone discovers you and claims you for themselves. Claims you are you because they found you. Claims you are theirs because they were the first to find you, and lay claims on you [. . . ] not knowing you’ve known yourself for thousands of years. Not knowing you are not the monster. (20-1, emphasis in original)

Having "discovered" Little Boy (Nathan Dubois) in his television, the atomic bomb test dummy Fatman (Allan Morgan) adopts him for his own "nuclear family" in Burning Vision. Produced by Rumble Productions. Photo: Tim Matheson

Display large image of Figure 4

26Little Boy is the voice of the earth, the voice of the unrefined uranium, the re/claimed native voice speaking out from the dark against the all-too-familiar colonizing voice of "Our Home and Native Land." The "discovery" of Little Boy on the floor of Fat Man’s home in front of the television seems to Fat Man to be his discovery, the white man’s discovery. In Fat Man’s living room, the television and the CBC-TV loon broadcast on it seem to cause Little Boy’s appearance (45). Fat Man is confused by "his" discovery of Little Boy; Little Boy cares little for the hows and whys of his present situation—he only wants "to go home" (46), to be one again with his land, away from the two-dimensional image of the pseudo-saviour, multicoloured Indian Chief figure who is thoroughly inaccessible through the man-made technology of the television screen (46).8 The television screen is connected, in a McLuhanesque sense, to Fat Man, who declares on his first appearance, "I am part of the cultural revolution, a cultural revolution that hears alien footsteps coming" (34). But who discovers whom? Object and subject experience reversal. Clements questions the act of discovery as fearful for those on both sides.

27 Discovery is also written into the design elements of Clements’s script. Lights emanate from characters’ props: flashlights, flames, the sidelamp, the television, and helmet lights. The First Movement stages the Bros. Labine frequently discovering other characters with the light of their flashlights, as if discovering various minerals in the earth and divining their individual stories. It is the human being, and not an external source, that illuminates each character’s own and shared spaces and their discoveries. The individualized lighting design problematizes the traditional Western colonial narratives of Discovery, Salvation, and Revelation. Such narratives thrive when the mechanism for "shedding light" on the "savages" who heretofore have "lived in the dark" are left concealed and unquestioned. In traditional stage lighting, Lekos and Fresnels shine light from above, hidden in the heavens of the stage grid. The narratives of Naturalism prescribe hiding stage lighting sources to give the sense that all on stage is visible for the audience’s socio-scientific study. But Little Boy sees through the lie when he says, "The real monster is the light of these discoveries" (41), not those who are discovered within the light. The divine illumination of the Hank Williams song "I Saw the Light" and its refrain, "Then Jesus came like a stranger in the Night. / Praise the Lord I saw the light" (25), is played and problematized by Clements, who stages the questions: What is the light? Where does it come from? And what histories does it not discover?

Conclusions

28 The world of Burning Vision is not that of a single, authoritative and authorizing memory; rather, the world is polyspatial, polytemporal, and polyvocal. Traditional Aristotelian Time and Space unities are freely dismantled and recombined. The unity of Action does not rest at the level of a single, central conflict; rather, the play’s dramatic action is held together in a transpiritual connection that bridges the markers of the Roman calendar, national borders, natural geography, and the elements of fire, water, earth, and air. By circumscribing the play with the Dene See-er’s vision, Clements infers that events in the context of prophecy are important not because they occur in a particular chronological order, or because they are set in motion by the victors, but, rather, they are important in spite of time and space, in spite of received historical narratives. But this is no nihilistic phenomenology. Here, events are staged in ways that foreground a multivocal (comm)unity of peoples across the planet. Like Fat Man and his nuclear family, we are all bound to each other, to the earth and to the multicoloured, multimedia airwaves. Memory and received history are first made illusive, then renegotiable. They defy claims of universality because it is, finally, each audience member who must map these worlds for her or his own, individual act of (re)writing and (re)historicizing, his or her own re-visions. In this sense, all audience members are positioned as historiographers confronting unmapped, performed territory. Burning Vision counters and re-encounters received histories in ways that deny the colonizer’s and aggressor’s oppressive strategies of mapping the space of the "undiscovered country," and of grafting linear histories onto indigenous and targeted peoples. Clements’s play attempts no less than the remapping of post-Hiroshima North America and the rehistoricization of its received narratives. Characters embody and exchange collective memories that work within and against received Western histories to form a matrix of dialogic conversations. Clements’s historical re-vision attempt nothing less than a reordering of narrative (hi)storytelling and a reexamination of the power dynamics inherent in wielding cultural authenticity while the post-Hiroshima "walls of the world" are tested again and again.

29 Burning Vision’s chronotopic dramaturgy proposes time-spaces moved from localized and confining authenticities—those that assert that to speak of a culture one must be born of that culture—to an alternate time-space in which, having listened and experienced mutual understanding, we can now speak about (not for) one another, to be heard fairly. The fact that Clements is Dene-Métis, and neither Japanese American nor Euro-American, exemplifies just such an intercultural handshake. Clements’s personal attachment to the events of her play are undeniable:"You write things you’re very passionate about. [. . . ] Having lost a lot of my Elders made me hyper-aware and sensitive to radiation poisoning. [. . . ] Ultimately, what I try to hang on to is the spirit of hope, the human capacity to believe in the best and to aspire to just that" (quoted in Lin).Louis Owens articulates this "intensely political situation" (15) extant at the locus of authenticity and hybridity in Native American writing, wherein the native author identifies herself as "Indian" in order to establish authority while manufacturing a discourse that is "internally persuasive for the non-Indian reader" (14). The authority generated by consciously foregrounding one’s ethnic authenticity, as creator, is the very same that can destabilize the hybrid ideology that is central to reciprocal intercultural dialogue. That Burning Vision may be understood through lenses of Dene experience is indisputable—indeed, its brand of chrono-topic dramaturgy is defined by these experiences—but it must be remembered that to employ exclusively a localized optic of reception proposes imbalance to the very ideological mechanisms of redress in the work itself. It is a tension that haunts both intercultural authorship and intercultural reception.

Works Cited

Bakhtin, M. M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: U of Texas P, 1981.

—. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Ed. and trans. Caryl Emerson. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1984.

Bird, Kai, and Lawrence Lifschultz, eds. Hiroshima’s Shadow. Stony Creek, Conn. : Pamphleteer’s, 1998.

Blondin, George. When the World Was New: Stories of the Sahtú Dene. Yellowknife: Outcrop, 1990.

Carlson, Marvin. Speaking in Tongues: Languages at Play in the Theatre. U of Michigan P, 2006.

—. "Theatre and Dialogism." Critical Theory and Performance. Ed. Janelle G. Reinelt and Joseph R. Roach. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1999. 313-23.

Clements, Marie. Burning Vision. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2003.

Gilbert, Helen, and Joanne Tompkins. Post-Colonial Drama: Theory, Practice, Politics. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Gilbert, Reid. "Marie Clements’s The Unnatural and Accidental Women Theatre Research in Canada / Recherches théâtrales au Canada 24.1-2 (2003): 124-46.

—. "Profile: Marie Clements." Baylor Journal of Theatre and Performance. Special ed. Nations Speaking: Indigenous Performances across the Americas 4 (2007): 147-51.

—. "‘Shine on Us, Grandmother Moon’: Coding in Canadian First Nations Drama." Theatre Research International 21.1 (1996): 25-32.

Helm, June. The People of Denendeh: Ethnohistory of the Indians of Canada’s Northwest Territories. Kingston: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2000.

—. Prophecy and Power among the Dogrib Indians: Studies in the Anthropology of North American Indians. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1994.

Hida, Dr. Shuntaro. "The Day Hiroshima Disappeared." Ed. and trans. Fumiko Nishizaki and Lawrence Lifshchultz. Bird and Lifschultz 415-32.

Hogan, Michael J. "Hiroshima in History and Memory: An Introduction." Hiroshima in History and Memory. Ed. Michael J. Hogan. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1996. 1-10.

Joki, Ilkka. Mamet, Bakhtin, and the Dramatic: The Demotic as a Variable of Addressivity. Abo (Finland):Abo Akademi UP, 1993.

Kernan, Alvin. Crossing the Line: A Bluejacket’s World War II Odyssey. Annapolis: Naval Institute P, 1994.

Keyssar, Helene. "Drama and the Dialogic Imagination: The Heidi Chronicles and Fefu and Her Friends." Modern Drama 34.1 (March 1991): 88-106.

Knowles, Ric. The Theatre of Form and the Production of Meaning: Contemporary Canadian Dramaturgies. Toronto: ECW, 1999.

"Lakota Topical Pain Reliever" [commercial]. CBC Newsworld. Toronto. 24 December 2004.

Lin, Brian. "Tuning into humanity with Burning Vision." Raven’s Eye 5.12 (April 2002): 8.

Malkin, Jeanette R. Memory-Theater and Postmodern Drama. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1999.

Owens, Louis. Other Destinies: Understanding the American Indian Novel. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 1992.

Schwenger, Peter. "America’s Hiroshima." boundary 2 21.1 (Spring 1994): 233-53.

Sherwin, Martin J. "Hiroshima and Modern Memory." Bird and Lifschultz 223-31.

—. "Memory, Myth and History." Bird and Lifschultz 343-54.

Treat, John Whittier. "Hiroshima’s America." boundary 2 21.1 (Spring1994): 233-53.

Velie, Alan. "The Trickster Novel." Narrative Chance: Postmodern Discourse on Native American Indian Literatures. Ed. Gerald Vizenor. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico P, 1989. 121-39.

White, Hayden. "History as Fulfillment." 12 November 1999. 11 June 2007 <http://www.tulane.edu/~isn/hwkeynote.htm>.

Notes

Burning Vision premiered at Vancouver’s Firehall Arts Centre in April 2002, commissioned by Rumble Productions and previously developed with Playwrights’Workshop Montréal. It has since played at the Festival des Amériques in Montreal and The Magnetic North Festival in Ottawa in 2003. The Vancouver production was nominated for six Jessie Awards, including best original script and best production. Its Talonbooks publication was nominated for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Drama, was shortlisted for the George Ryga Award for Literary Arts in 2003, and garnered the Canada-Japan Literary Award in 2004. For a valuable summary of Clements’s early work, see Reid Gilbert’s "Profile: Marie Clements."