Articles

Navigating the Prague-Toronto-Manitoulin Theatre Project:

A Postmodern Ethnographic Approach to Collaborative Intercultural Theatre

Barry FreemanUniversity of Toronto

Abstract

This paper considers critical approaches to collaborative intercultural theatre using the Prague-Toronto-Manitoulin Theatre Project (PTMTP) as an instrumental case study. It begins by contrasting orderly and coherent accounts of intercultural theatre with the more messy and confusing experiences of it. Taking a poststructural view of culture, this paper suggests that postmodern ethnography is well suited to access the experiential dimension of theatre work, making it a valuable addition to existing semiotic strategies and models. Looking at the kinds of insight offered by semiotic and ethnographic approaches, the author discusses a particular scene from the PTMTP, first suggesting how it may have appeared to its audience in public performance and then analyzing how it was experienced and interpreted in development and performance by both himself and several of its creators. Though postmodern ethnography has its practical limitations, it is hoped that its application in this context sheds light on the meanings made available to particular critical approaches.Résumé

Cette contribution examine les approches critiques appliquées au théâtre interculturel collaboratif à partir d’une étude de cas, celle du Projet de théâtre Prague, Toronto et Manitoulin (PTMTP). Freeman commence par mettre en contraste des témoignages ordonnés et cohérents du théâtre interculturel avec des expériences plus embrouillées et déroutantes. En adoptant une perspective poststructurale de la culture, Freeman fait valoir que l’ethnographie postmoderne nous permet de saisir la dimension expérientielle du travail théâtral, ce qui constitue un apport précieux aux stratégies et aux modèles sémiotiques déjà en usage. À l’aide de certains points de repère empruntés aux approches sémiotique et ethnographique, Freeman examine une scène tirée de la coproduction PTPTM pour montrer dans un premier temps quelle aurait pu être la perception des membres du public qui assistaient à la représentation. Ensuite, il analyse la façon dont cette même scène a été vécue et interprétée par lui-même et par plusieurs autres créateurs qui participaient au projet pendant la période de création puis lors des représentations. L’ethnographie postmoderne a des limites d’ordre pratique, mais il est à souhaiter que son application dans ce contexte nous permette de mieux saisir les significations dégagées par certaines approches critiques.Introduction

1 The last decade has seen a rise in popularity of collaborative intercultural theatre projects that bring artists of different cultures together to create original work. Toronto has been home to a number of these projects, several of which are ongoing.1 This essay takes a critical look at the partly Toronto-based Prague-Toronto-Manitoulin Theatre Project (PTMTP), with which I was involved between 1999 and 2006 first as a performer, then as an assistant director, and finally as a researcher. My involvement with the project as a practitioner and a researcher has given me the opportunity to examine how critical approaches to it may privilege certain meanings while disregarding others. In this essay, I will outline and put into use an alternative critical approach to inter-cultural theatre: postmodern ethnography. I will argue that post-modern ethnography is a particularly appropriate approach to the culturally complex environment of collaborative intercultural theatre. Later in the essay, I analyze one specific scene from the PTMTP’s 2006 performance, The Art of Living by contrasting a semiotic reading of the scene with an ethnographic analysis of personal narratives of PTMTP participants from interviews conducted in 2006 and 2007. The result is a glimpse into the fraught operations of artistic process, identity, and (mis)perception.

2 The theorization of interculturalism in the theatre and the development of theatre semiotics have been closely related. The structuralist semiotic interest in universally valid codes and patterns of performance made it particularly useful to those twentieth-century Western avant-garde theorists and practitioners who looked or travelled elsewhere in the world in search of new ideas that would interrupt their own nationalist and bourgeois theatre traditions. The first generation of this group included Craig, Artaud, and Brecht, each of whom had the opportunity to see foreign performers on tour or at World Exhibitions in the West. The second generation of this group includes Mnouchkine, Brook, and Wilson, and in a more anthropological strain, Schechner and Barba. Generally, this latter generation was interested in the transfer of narrative, image, and technique between cultures (see Bennett; Carlson; Elam; Fischer-Lichte, Semiotics; and Pavis, Theatre) and in alignment with what has been variously argued to be a transcultural, paracultural, or precultural ideology (see Pavis, Intercultural).2

3 For some time now, both intercultural practices and structuralist semiotics have been under revision. This has partly been a response to criticisms of some intercultural practices as "ethnocentric" (Bharucha 3) or "corrupt" (Eckersall 217) and partly a response to poststructuralist arguments from cultural studies and anthropology that regard culture as contingent, contextual, and performed. The latter involves an epistemic shift away from a positivist epistemology that imagines culture to be determined by knowable codes and theories, toward a postpositivist one that rather works towards interpretations of culture in specific situations and at specific moments. In semiotics, this shift has been away from a positivist "science of culture" (Lucy 16) and toward sociological or materialist analyses of signs in specific social contexts, relationships, and configurations of power (see Esbach and Koch; Hodge and Kress). Intercultural practice has shifted by developing—or rather absorbing—dramaturgies based on more egalitarian principles, with collaborative intercultural theatre as one result. Intercultural theatre theory has also shifted away from more structuralist theories of intercultural interaction, such as Pavis’s hourglass model (see Fischer-Lichte, Riley and Gissenwehrer; Pavis, Theatre), toward those more mindful of politics, agency and context (see Shevtsova; Lo and Gilbert; Pavis, Analyzing; Turner).3

4 The same shift has occurred in ethnography. Links between ethnography and theatre studies were forged in the 1970s by such scholars as Erving Goffman, Victor Turner, and Richard Schechner, whose pioneering work penetrated the disciplinary boundaries between anthropology, sociology, and drama. Much of this work was modernist insofar as its pursuit of grand theories all but erased cultural difference and silenced its human subjects. Strangely, theatre studies since then has taken little advantage of developments in ethnography, even though postmodern ethnographers have been interrogating theory and methodology from post-colonial (see Clifford; Clifford and Marcus; Geertz; Conquergood) and feminist perspectives (see Acker; Fine; Lather; Smith).4 What has been at stake in this re-evaluation, writes James Clifford, "is an ongoing critique of the West’s most confident, characteristic discourses" (Clifford and Marcus 10). This paper will demonstrate three features of my own conception of postmodern ethnography: a reorientation toward a poststructural view of culture, an erosion of distanced critical objectivity in favour of situated knowledge and reflexivity, and the opportunity to explore meaning-making in the theatre through personal narratives.

The Prague-Toronto-Manitoulin Theatre Project

Program Excerpt

After three previous successful projects, Man and Woman (1999-2000), I and They (2001-2002) and Myths that Unite Us (2003-2004), we are following up with the fourth, titled The Art of Living (2005-2006). This project is a unique cultural and pedagogical collaboration between students of the Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, [sic] (who also comprise the STUDIO of the Studio Ypsilon) and students from the Drama Section of theVisual and Performing Arts of the University of Toronto at Scarborough. This unusual undertaking is supervised jointly by the founder, managing and artistic director of the Studio Ypsilon, Professor Jan Schmid on behalf of the Czech Group, and Michal Schonberg, professor, dramaturg and author, for the Canadian side. As was the case during the third project, the group is once again enriched by the participation of members of the First Nations theatre group Deba-jeh-mu-jig, based on Manitoulin Island in Northern Ontario. Led by Artistic Producer Ron Berti and Artistic Director Joseph Osawabine, this native professional company aims mainly at preserving the native cultural heritage, bringing theatre to distant communities and training native young performers. (Art of Living)

5 It is perhaps already evident that I am not interested in documenting the PTMTP or in ‘evaluating’ its ‘success,’ but rather in using it as an instrumental case study (see Stake 445) that addresses wider theoretical and methodological issues. With this in mind, I choose here to take the unusual step of not beginning with a comprehensive description. The three brief texts that I begin with here do introduce the project, but I also mean for them to illustrate the disjuncture between the tidy and predominantly positive ‘official’ accounts of theatrical work and the messy and often unresolveable experiences of it. The preceding text is a good example of the former type, taken from the program to the fourth incarnation of the project in 2005-2006, The Art of Living. As an introduction to the project, the description provides basic information about the institutional and individual participants. As a source text for analysis, it offers little to comment on, save for one interesting detail: that De-ba-jeh-mu-jig (Debaj) is framed as an "enriching participant" rather than a member of a tripartite collaboration. While the description still accords Debaj the distinction and respect that they received throughout the collaboration, this detail nonetheless provides a clue about Debaj’s unique position in the project—not a part of the original design, smaller in its number of participants than the other groups, and at times disappearing into a wider ‘Canadian’ identity within the ensemble. This detail, however, only becomes a clue with further knowledge of the project; for the most part the text confidently announces the project to be a cohesive, mutually enriching collaboration. Something of the same impression results from the following:

The PTMTP’s Process

The devising process of the four projects differed slightly, but a general description is possible. Each time, the groups began by each working separately on the theme in its own way according to its own tastes and talents. [. . .] Schmid then traveled to Canada to co-facilitate a two-week workshop [with Schonberg...] Building on what had been generated prior to their arrival, the facilitators led the Debaj and UTSC students through more structured creative work. In the case of each project, for instance, participants had been asked to produce written responses to a set of questions on the theme, from which Schmid and Schonberg chose items to dramatize. [. . .] Meanwhile, [musical director] Jan Jirán taught the participants music of his own composition, with lyrics provided either by participants or, later, by Daniel David Moses. These elements—personal reactions and musical interludes—were then combined with tightly choreographed sequences of movement, gesture and sound of Schmid’s own composition. The end result was a "workshop performance" for an invited audience only. Schmid and Jirán then returned to Prague and soon after directed the Czech students through a similar process. Some months later, the UTSC and Debaj groups travelled to the Czech Republic for a three-week stay. [. . .] After the Prague opening, the ensemble travelled to the north Bohemian town of Liberec. [. . .] Two weeks after the UTSC/Debaj ensemble returned to Canada, it hosted the travelling Czech group [. . . and] the show was performed at the University of Toronto at Scarborough and the Graduate Centre for the Study of Drama in Toronto. The entire ensemble then travelled to Manitoulin Island, where performances were held at Pontiac Public School in Wikwemikong and at Manitoulin Secondary School in West Bay. (Freeman, "Cultural" 219-220)

6 This text describes the process rather than the players, affecting a neutral rather than promotional tone. For my present purposes, what is interesting about it is that its neutrality is feigned; the information it relates came (and could only come) from first-hand experience of the process. When I wrote this passage I worked from memory rather than documents, in the process converting an array of memories of colourful experience, personal relationships, and conflicted emotions into reportage. I adopted a distanced, objective voice that carefully obscures my proximity to the subject and steers clear of both interpretation and evaluation. Though the passage is based on embedded ethno-graphic research, it does not reveal itself as such. Consider the different impression of process that follows from a third text:

Field Notes, 2 May 2006

First day of rehearsal. We meet at Ypsilon at 9, and begin work. We’re on their mainstage—a gorgeous warm space with playful colours and an intimate atmosphere. We start with a warmup, then start music. Jenda teaches the group Czech songs, then both Czech and Can groups sing their own songs for one another [. . .] The actors are noticeably quiet, hesitant. [...] The idea comes up to do a visual representation of the story of the Northwest Passage song. I throw in David’s idea of having the Native perspective on exploration represented as well. It isn’t easy to communicate why this should be so across the language barrier to Václav. He only seems to understand me after I explain the geography of the thing—polar explorers entering space occupied by natives. (Ironic that Debaj—Cree and Ojibwe—is about as culturally foreign to those of the north as the Czechs are, but reducing the idea geographically seems to have made it understandable). David then wonders if we could work Debaj’s territory scene in somehow. David seems hesitant. I can’t read him, but I suspect he’s concerned about whether this can/should really be done. I’m thinking back to my earlier conversation with him, and wondering: Is the cultural collision/convergence itself culturally relative? To me, it’s theatrically interesting to see them create something new together, but David has described the same as cultural homogenization. Who is invested in the groups’ coming together? Who wants particular voices to be heard? Why? What’s actually going on? (Freeman, Unpublished)

Of course each of these texts has a unique purpose and immediate audience: the first text means to convey something of the project’s genealogy and structure to its audience; the second wants to relate something about dramaturgy to an academic readership; and the last is a private rumination hoping to capture something meaningful about the mechanics of intercultural collaboration. The program excerpt promotes the work in glowing terms; the description strikes a distanced, authoritative tone; and the field notes are invested and conflicted, briefly alluding to a potentially difficult creative negotiation. While the first two are polished representations, the third contains a more ‘raw’ kind of information that invites further analysis. All three texts, however, represent something of a complex process according to their own biases and ideological investments, and no one of them possesses a greater ‘truth value’ than the others. In the next sections of this paper, I will expand on why I think qualitative data such as this last text—an excerpt from notes I took while working on the PTMTP in Prague—is especially valuable in relation to intercultural theatre. To this point, I hope that these texts situate the reader in what is for me a productively uncomfortable position among competing narratives: on the one hand, accounts of intercultural theatre work as strictly positive and orderly, producing a polished product representing the salient features of the collaboration, and on the other, the experience of the work in the rehearsal room and onstage as messy and conflicted.

Toward a Postmodern Ethnography

7 In his still influential essay "Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture," Clifford Geertz addresses the question of what the ethnographer does. One of his answers is that "[the] ethnographer ‘inscribes’ social discourse; he writes it down" (19, emphasis in original). Geertz suggests that one cannot separate readings of social discourse from the specific situation of their utterance, that to "divorce [interpretation] from what happens— from what, in this time or that place, specific people say, what they do, what is done to them [. . .] is to divorce it from its applications and render it vacant"(18).

8 Geertz’s suggestion may be thought to be less germane to theatre analysis than it is to ethnography, insofar as the matter of where we locate social discourse in the theatre hinges on a set of aesthetic and philosophical considerations. My contention here, however, is that the creative and cultural negotiations at play in intercultural theatre work mean that the happenings, sayings, and doings of theatrical process must be admitted as an additional site of social discourse. Theatrical process involves rich moments of artistic, personal, and cultural negotiation, many of which (the unpleasant ones in particular) are erased in the production of a polished and orderly play text or performance. If, following Geertz, we ask what postmodern ethnographers in the theatre do, the answer is that they explore the messy and conflicted in the social discourse of theatre—whether that be in a play-text, on-stage, or in a rehearsal room—from the perspective of an implicated participant and at specific moments. In my view, understanding how both collaboration and interculturalism operate requires an approach that celebrates the messiness of process: its multiple messages, delicate negotiations, conflicting perspectives, and accidents of creativity. The value of postmodern ethnography is that it seeks out (and is not obliged to quickly tidy) that messiness.

9 The scattered, incomplete, obscure, and self-contradictory nature of experiential data is precisely its value. From a postmodern and poststructural perspective, culture has these same qualities. The modernist locus of culture is the coherent self that inherits and carries forward a cultural tradition, whereas culture in postmodern perspective is always dependent on context and relationships, is always open to revision. According to influential ethnographer Dwight Conquergood, challenging the modernist paradigm leads to "a rethinking of identity and culture as constructed and relational, instead of ontologically given and essential" (184). In "Ethics: the failure of positivist science," Yvonna S. Lincoln and Egon G. Guba dispense with a "conventional" cultural paradigm premised on the symbolic coherence of culture, because, they argue, it requires "treating human research subjects as though they were objects" (224). Lincoln and Guba favour a "naturalistic" paradigm based on the idea that "social realities are social constructions, selected, built, and embellished by social actors (individuals) from among the situations, stimuli, and events of their experience"(227). If intercultural work like the PTMTP opens a new space between cultures, Homi K. Bhabha’s performative "third space" (37) that Janinka Greenwood says "emerges through cultural encounters," (194), then its thirdness is only provisional—it is individuals that occupy this space, and whose actions make change possible. I make virtues out of the messy, provisional, and incoherent qualities of theatre work because I believe culture to have these same qualities. For me, these are not qualities to be fixed or ordered, but rather defining features of intercultural theatre work with creative and emancipatory potential.

10 Of course because "writing it down," as Geertz put it, inevitably fixes and orders, some compromise must be reached. The postmodernist ethnographer considers the givens of theatre work, its features, circumstances, and the often naturalized and "official" narratives, scripts, or metaphors that form around it, but adds a creative exploration of how the work is variously experienced by the participants (him/herself included). Participants themselves will always elude ordering because they are not wholly determined by their circumstances. Their unique ideas and self-positioning often complicate and challenge the givens. The ethnographer’s challenge is to build a site of analysis without too quickly disregarding any of the artistic, cultural, and politically charged negotiations that comprise theatre work. The goal is not to work toward predictive conclusions or totalizing models, but "inscriptions of social discourse" that interpret what has been said and done.

11 In the next section, I attempt an ethnographic approach in a discussion of a particular scene, both as it appeared in the public performance and as its development was understood by some of those who performed in it. The scene, already referenced in my field notes above, is from the 2006 incarnation of the PTMTP, The Art of Living. I choose this scene not because it was typical, but because it was atypical, the result of uncomfortable—if accidental—compromises within the ensemble. It is a counterpoint to the notion of an ordered and harmonious collaboration, providing an alternative perspective on how collaboration works (or fails to work) in the intercultural context. The following account and analysis of the scene’s development illustrates those features of a postmodern ethnography cited in my introduction: it takes a post-modern view of culture by looking to how it operates in a specific context, and how individuals exercise their agency in engaging with and challenging fixed cultural identities and subject positions; it shirks critical objectivity by implicating me in the analysis and keeping in mind how my own presence in the theatrical and research processes might be significant; and it approaches some issues of significance to intercultural theatre by analyzing the personal narratives of its participants.

Navigating the Northwest Passage

12 The Art of Living took a broad interpretation of its title theme, consisting of playful skits and rapid-fire stories and musings about both the artfulness of everyday life and place of formal art in the personal lives of the performers. About halfway through the show, however, was a scene that set a different tone. While it had some of the same air of playfulness and levity as the rest of the show, it also depicted a violent encounter that culminated in an ambiguous moment.

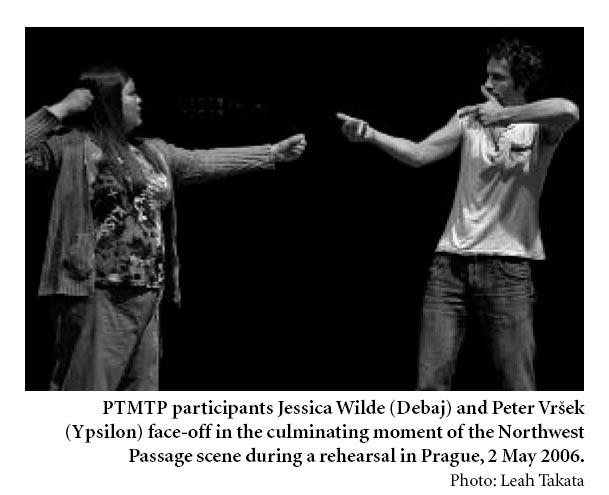

PTMTP participants Jessica Wilde (Debaj) and Peter Vršek (Ypsilon) face-off in the culminating moment of the Northwest Passage scene during a rehearsal in Prague, 2 May 2006.

Display large image of Figure 1

13 Sitting in the audience at Ypsilon Theatre in Prague on opening night, 14 May 2006, I saw a scene that depicted a first contact, ostensibly between North American Natives and Europeans, and scored by a chorus singing a re-arranged version of Canadian folksinger Stan Rogers’s song "Northwest Passage," an anthem to the heroism of polar explorers. Debaj actors played the Natives, Ypsilon actors played the Europeans, and UTSC actors formed a chorus. The scene begins with the Natives entering the space to the pulse of a drum and wordlessly trading items that they happen to have in their pockets. Seemingly satisfied, they separate to the four corners of the stage. Next, the Europeans enter the scene upstage, behaving boorishly, evidently trying to decide where to go, and speaking gibberish that crescendos with the declaration "West!". As the chorus sings "Northwest Passage," a scene plays out between the Natives and Europeans quickly and in broad farcical strokes supported by comic gestures. The Europeans form a line, miming a rowing action, and one seems to step out of the boat to ask (in English) what this land is called, to which the Native replies "Kanada," playing out the familiar (and probably apocryphal) story of the misunderstanding between Jacques Cartier and the Iroquois that gave Canada its name. The Europeans continue to row, and a bloody war erupts between them (still using comic—at this point cartoonish—gestures) that leaves only one Native and one European standing at the end. The two survivors point their weapons at each other, not knowing what to do next (see image), at which point the European leans in, kisses the Native, laughs, and bolts offstage, leaving the Native to pass a rather blank look at the audience. The scene closes with everyone reentering to sing a final chorus of "Northwest Passage."

14 This is how I saw the scene, but of course I had seen every step of its evolution and (mostly) understood its historical references. I cannot say how it was understood by my fellow spectators that evening, but I can only imagine that most would have seen a broad, uncomplicated Eurocentric vision of the conquest of the New World. Consider the use of stage space: (i) the Debaj actors enter first and move slowly and comfortably around the stage until (ii) the Ypsilon actors enter into the strong space on the stage which they occupy until the end of the scene, and (iii) the UTSC actors observe from the periphery throughout. All of this could be read as realizations in proxemics of a familiar story: a conquest narrative depicting the Natives as a single peaceful community ruined by European invaders who first misunderstand, then kill, then symbolically rape their victims with a final, stolen kiss. Those who could understand the lyrics of the song would find a similar theme in its repeated lines "Tracing one warm line / Through a land so wild and savage." A structuralist semiotic reading might look like this, building an interpretation out of the accumulating meaning of stage signs.

15 A more social or materialist semiotic approach might then use that interpretation to comment on the broader intercultural collaboration between the companies and, by extension, on the historical/political relationships between their respective cultures. Perhaps, as an example, one might suggest that a parodic approach to the conquest narrative allowed the ensemble to playfully act-out an ill-fated story of cultural encounter, confronting and perhaps even exorcising some of the historical ghosts that haunted this particular collaboration. A more nuanced reading might further question how the scene may have been intended and received. Why would Debaj, for instance, choose to tell that story? The choice of language seems to suggest that the scene issues from their perspective: aside from the words "Kanada" and "West," the only performers who speak are the Europeans,who do not charge forth with English or Czech (both of which these performers could have spoken) but in gibberish, as though the perspective on this story is that of the uncomprehending natives. The choice to use gibberish, one might guess, followed from Ypsilon performers’ perception that this whole theatrical idea was, in fact, issuing from the Debaj/UTSC groups, and thus was effectively for them. The Czech audience, after all, would not be familiar with the Stan Rogers song, nor the Canadian Heritage moment parodied, nor with contemporary historiography that would challenge the image of Natives living in harmony prior to colonization, nor with the ins and outs of historical and geographical circumstance that the story effaces.5 For a Czech audience, the scene surely functioned in a kind of symbolic register, but as surely for the Native actors it was a story with specific and local resonance. At this point, one might productively look for support in reviews of the performance, if such existed.

16 Even these half-drawn semiotic readings are insightful, but I would be suspicious of each for different reasons: of the structuralist reading because it is too tidy and of the social/materialist reading because I would not expect that the groups could (or would) represent themselves so straightforwardly. Suspecting that the cultures were interrelating in more complex ways, I would want to know more about the sensitive negotiations, mutual misperceptions, and uneasy compromises that I know characterize the processes of collaborative intercultural theatre. These would tell me more about how these cultures perceived one another and saw themselves reflected in this representation. This would be to approach a different set of themes, such as mutual (mis)perception, the negotiation of cultural identity, and the possibilities and limitations of intercultural dialogue in theatrical process. Let me now, then, approach the same scene ethnographically.

17 As the assistant director of the project, I watched the scene develop from start to finish, and in its specific case, had quite a bit of creative input. Its genesis had been months before the groups even met, when the UTSC group decided to sing "Northwest Passage" as a vocal warm-up. During a warm-up in Prague, director Jan Schmid heard the song, had it translated, and suggested it be expanded into a scene. Not knowing why we were doing it—or how it could connect to the show’s theme—myself and some other facilitators set about combining the song with some other ideas that had come up. Despite being at its centre, however, the aimlessness of the process left me with the feeling that I recorded in my journal of witnessing "a series of bizarre accidents." Accidents perhaps, but accidents that I nonetheless was myself engineering, assembling pieces that suited different participants and (perceived) interests, but not knowing what whole those pieces were making. I knew someone else felt the same way when, during a rehearsal of the scene, one of the Debaj participants handed me a small piece of paper on which was written a line that he proposed should preface the scene: "We live our lives with a patchwork history of missing information and misunderstanding." It was a poignant moment that immediately changed my own perspective of the work unfolding in front of me.

18 That moment stuck with me. By this stage of my research, I was developing an ethnographic approach to the work, and was conducting interviews of participants from each of the PTMTP’s groups. Ethnographers, of course, have been working with "informants" for decades, but postmodern reformulations of ethnography that have broken down positivist authority have only increased interest in the

personal narratives of ‘informants,’ seeing narrative as a natural human mechanism whereby we try to come to terms with—without necessarily smoothing over—a disordered or difficult reality. Narrative, writes Donald Polkinghorne, "is the linguistic form that preserves the complexity of human action with its interrelationship of temporal sequence, human motivation, chance happenings, and changing interpersonal and environmental contexts" (7). Even after theatre work takes place, participants in collaborative intercultural theatre who story their experience are still engaged in the process of negotiating cultural identity—their own as well as those of others. With this in mind, I decided to make of the northwest passage scene a study-within-a-study by asking participants: What do you think of the northwest passage scene, either how it came about, or what you think it means? Here are some excerpts from their responses (names are pseudonyms):Paula (Debaj): How does anybody decide what is going to be in the show? That to me is the big question…. So there’s a song…. But then I feel a little bit like so then we come in and because we’re the aboriginal group, then we have…. ‘There’s this beautiful song, but it’s not really inclusive to aboriginal people,’ which is of course true…. But then I feel like we create this thing that is reactionary to something. Which is—I don’t really understand how it relates to the theme anyway. So for me the whole thing is just ‘How did it get there?’ (Paula)

Melanie (UTSC): Stand over there and hum,because we’re going to get the Czechs to perform this—act this out. And the Natives going ‘This isn’t—wasn’t actually our history. We have no idea if this is how it really happened.’ ‘Yeah, no, trust us’. And someone finally said ‘You have to say that we don’t know that this is the history’. ‘Oh, OK’. [laughter]…. That’s the reality of it. How it’s presented, and how it would be spun by someone who knew what they were doing would be this beautiful collaborative and cultural blending moment…. I totally think that’s how it looks… I think that it’s a fiction. I think that it is theatre at its purest. (Melanie)

Veronika (Ypsilon): Ok, so I know the story. I know that the first part is about exchanging some… Like when the Debaj is on the stage, looking for a new place, exchanging some things. Actually I don’t know why. I know we were talking about it, but I forgot about it. Then also, it was probably that Czechs should be involved in some Canadian part of the play or something. So it’s like trying to… uhh… fit people in the Canadian part of the play. (Veronika)

Katja (Ypsilon): It was like some Canadian, some Native stuff. The first man who came to a Native place and killed some Natives, or not killed, and nobody knows how was it, or if he was like a martyr, or hero, nobody knows. And it was like, something important in Canadian history. That’s it. But I mean, like, Canadian stuff. [...] I didn’t really feel some nation proudness because it’s not my stuff— it’s your history, it’s Canadian history. (Katja)

David (Debaj): We still mixed all kinds of things together in there, you know…. I thought it was kind of neat how Europeans were represented, the way that mainstream Canadians were represented, and the way that Indigenous peoples were represented. And I think that we could have gone a lot farther with it too, but I think that was enough change from where it started for us to feel comfortable, you know? Ideally there would have been more priority around the roles of these different communities…. Well I think in terms of content, for me personally, it turned out to be the richest part of the show…. Because it brought the three distinct groups together in a meaningful way in one piece. (David)

19 Among the many issues these brief comments raise for me are the disjuncture between meanings generated in the process and product, intercultural interaction as inter-reaction, discomfort with the project’s structures of artistic control, and the different attitudes participants have towards the political position of their own culture in relation to those of others. Paula’s comment, for instance,is part of a longer discussion about her own thoughts visà-vis the position of Natives in Canadian society in which she expressed her feeling that, for her, the time is past for reactionary anger and the time has come to work toward creative, positive change. Her perspective on the northwest passage experience is disapproving, seeing in it the ‘same old’ reflexive and oversimplified reaction to being excluded. There’s a sadness and frustration in her comment that suggests that it isn’t the first time that she has been in the position of having to provide a token reaction to being excluded. The questions she poses—"How does anybody decide what is going to be in the show?" and "How did it get there?"— speak to the fraught issues of artistic process and control which others also expressed difficulty with in interviews. For Paula, the lack of dialogue created limiting subject positions and funnelled the process through narrow and predictable channels.

20 Recall that in the semiotic reading of the scene’s performance, Paula played a doomed victim of European conquest and had little room to inflect her performance with irony or subversion. In the interview, Paula was able to position herself differently in the narrative of native subjugation, finding an opportunity to express what she could not during either the performance or the creative process. Similarly, Melanie, who in the scene was a member of the peripheral chorus singing the Stan Rogers song, separates herself very emphatically from any ostensible "meaning" of the scene. Adopting the voice of an authoritarian facilitator, Melanie points to how arbitrary the decisions that generated the scene appeared to her. Demonstrating the keen sense of observation that she displayed throughout our conversations, Melanie represents Debaj’s reaction to the scene here by adopting their voice in her imaginary dialogue. Her final comment in the voice of the facilitators, "Yeah, no, trust us," points again to lack of knowledge the participants had about what was informing artistic decisions. Another interesting idea Melanie proposes is that of the disjuncture between the meanings circulating in the creative process and the meanings delivered by the public performance. For Melanie, the scene could be read simply and positively by an imagined spectator as the coming together of cultures (despite its ‘story’), whereas the experience of creating it was almost divisive.

21 Her final remark, that this was "theatre at its purest" may have been a cynical comment on her detachment from the specific message or "fiction" conveyed by the PTMTP’s public performance, but it connects to a larger theme: the relationship between a tumultuous process of negotiation in rehearsal on the one hand and a public performance that must fix—in the senses of both "to correct" and "to set"—elements of that process on the other. This theme surfaces throughout contemporary scholarship about collaborative intercultural theatre. In an analysis of Singaporean director Ong Keng Sen’s work, for instance, William Peterson highlights a deep chasm between the experience of process and the experience of performing. Peterson notes that after the audience’s supposedly "unforgiving" reaction to Sen’s Desdemona at the 2000 Singapore Arts Festival, Sen responded that Desdemona was about "reviewing the process of coming together as an intercultural group"(89) and that it was important to him "to produce a process rather than a product" (90). Peter Eckersall makes a similar observation about his work on the Journey to Con-Fusion project,noting the gap between how the work is understood by the participants and how it is received by its audience is a "strong point of contention" within that project. Journey to Con-Fusion, he writes, "exposes ideological and aesthetic tensions between the representational forces of exterior form and the motivational forces of interior work" (212). In the project, these tensions created anxiety for Paula and Melanie. In my work, tensions between internal motivational forces and external representation forces—those exposed by the texts I cited earlier—led to my own search for a new critical approach.

22 The comments from Czech participants Veronika and Katja are in sharp contrast to the others. They each chose to speak about what was happening in the scene rather than the politics of the process that generated it. Neither demonstrates any knowledge of the specific historical fragments on which the scene draws.In other respects their comments are quite different. Veronika forgets what was said about the scene even though it had been created only a couple of weeks previously, whereas Katja remembers it well even though she is speaking about it more than a year later. Veronika first claims to know the "story," but instead begins to offer a play-by-play of what happened in the scene without a narrative interpretation. She then cuts the play-by-play short, as though she hadn’t considered it much before and wasn’t sure what to make of it. Katja does provide a narrative: an ill-fated first contact between a European (a nameless but specific one) and a community of Natives. While the degree to which she lumps together the categories of Canadian and Native doesn’t demonstrate much of an awareness of the history and politics of each (the Czechs often referred to the combined USTC/Debaj contingent as Canadian), Katja went on after her comment to tie her interpretation into the history of Native subjugation in Canada and the legacy of residential schools. When I asked her how she learned about that history and context, she replied, "I was asking people, and they told me about schools, and that they were quite angry" (Katja). Though interesting, this seemed to go beyond the import of the northwest passage scene, which for Katja and Veronika both was part of a history that was unknown and inaccessible to them.

23 Veronika and Katja’s feeling that the scene issued from and belonged to the Natives or Canadians is ironic in light of Paula and Melanie’s apparent detachment from it. For me, this misperception illustrates the messiness of experience relative to a tidy interpretation. Any interpretation that rests on the assumption that performers in intercultural theatre are ‘representing themselves’ would seem to be undermined if they are, in fact, unaware of the historical or political resonances—or even, for that matter, the story—of what they are performing.In the case of a piece collectively created by dozens, who can blame Veronika and Katja for not fully understanding what was happening? One might see this as a failure on the part of the facilitators (that is, my own failure), but I think this is a phenomenon endemic to intercultural collaboration. Frankly, though I may have understood the scene’s references as well as anyone in the room, I also didn’t know what sort of creature the scene had become, what it might mean, or why it was there. In collaborative work there is this slippage of messaging and intent, here compounded by cultural unfamiliarity, and I value that the ethnographic approach exposes it, as uncomfortable and unresolveable as it can be.

24 Finally, and further demonstrating how ethnography resists easy conclusions, David’s optimistic (though qualified) endorsement of the scene in the last comment plays against the other perspectives. In even its first word—"We"—David seems to take up a responsibility for the scene that the others either don’t feel, don’t want, or both. It is unclear which We he invokes; I have the sense that it could have been both "We the participants in the PTMTP" and "We the two of us having a conversation." Like Paula and Melanie, David also focuses on the messages being delivered by the scene, but unlike them offers the comment that it was "neat" how each group was represented ("neat" being a surprising word choice, suggesting he takes the scene somewhat lightly).

25 The contrast between David’s and Paula’s comments is informative. Paula is frustrated by having no available subject position other than to offer a simple reaction. With no available means to negotiate any new subject position in the perception of those she was working with, the only one available to her was one of reaction to the colonizer’s story that restaged and reinscribed a dialectic that she wished to leave behind. David, on the other hand, is pleased with the character ("the richest part of the show") and extent ("it was enough of a change from where it started") of the reaction. For David, the northwest passage scene was a meaningful (and therefore successful) meeting of the three groups that rendered its deficiencies forgivable. For me, their different takes on the scene connect to a larger issue—that of how larger historical and official narratives effectively make some subject positions more available than are others, and how participants can (and do) go about negotiating new ones that can then, in turn, revise the narratives. Identity is always calcifying, and while I suggested earlier that positivist epistemology threatens to efface individual agency in the negotiation of cultural identity, it seems that participants’ own misperceptions and lack of knowledge can just as easily contribute to the fixing of cultural identity. Even in these brief comments one can see the ease with which individuals consigned other groups to definable subject positions within the collaboration and within a dialogue about the collaboration. Predictably, when I asked about their own subject position within their own group and cultural community, definitions came with far less ease.

26 With more space I would continue with this sort of analysis, but my main objective here has been to illustrate the different kinds of discussion that are generated by a postmodern ethnographic approach versus, for example, a semiotic one. My semiotic reading lent itself well to a discussion of aesthetics (the significance of the use of stage space) and historical context (implications of the historical material chosen). The ethnographic account, by contrast, lent itself to a brief but more nuanced discussion of the diverse perspectives and difficult compromises that comprise the processes of both devised dramaturgy and intercultural interaction. The semiotic reading pursued a coherent and convincing reading of the northwest passage scene, conjecturing, ultimately, about the nature of the groups’ (and their cultures’) interrelationships. The ethnographic analysis ran counter to this by illustrating that participants had differing ideas (and degrees of knowledge) about what they were representing and by revealing conflicting individual perspectives on participants’own cultures. The qualitative data was perhaps messy, but this is appropriate to the messiness of cultural negotiation in the creative process. Having spent so much time participating in and observing collaborative inter-cultural work, I find it impossible to limit analysis to the sort of tidy, coherent readings that semiotics—not to mention more structuralist models of analysis—can produce. Taking a postmodern view of culture, coherence is suspect. "Nothing has done more," writes Geertz, "to discredit cultural analysis than the construction of impeccable depictions of formal order in whose actual existence nobody can quite believe"(18).

The View from Here

27 It was not lost on Geertz, however, that "depictions of formal order" do exist and have their force. Whether a tidy account of theatrical process or a coherent semiotic reading that produces a consensus of meaning where one did not exist, interpretations always create some order out of the chaos of phenomena. In this paper, I have considered the kind of order that our accounts of intercultural theatre pursue.

28 Consider a different example. One of the effects that the social/materialist semiotic tradition continues to have on contemporary intercultural theatre scholarship is to locate social discourse in the material conditions of production and reception. Both Eckersall and Peterson do this, and both point to the aforementioned disconnect between process and product. Perhaps because they focus on reception, Eckersall and Peterson also both wonder whether intercultural work in performance can ever be more than an alimentary process of ‘consuming’ foreign cultures. This is an important consideration: there has always been social and cultural capital to be acquired from travelling around the world to collaborate with foreign artists and so some people will do it strictly for their own material gain and in performance of their affluence and ability to do so. The suggestion is not new—it has been particularly prominent in intercultural theatre discourse since the controversy surrounding Peter Brook’s 1985 production of The Mahabharata, famously used by Rustom Bharucha as a platform from which to critique the whole intercultural enterprise (see Bharucha). Like Bharucha, I too feel that there are many reasons— both historical and contemporary—to be skeptical about the potential of intercultural work. But is it not the case that at least some of its limitations or bleaker prospects are the inevitable conclusions of critical approaches that are no longer well-suited to it? I hope that my contribution to the intercultural discussion is to suggest how postmodern ethnography may help break this critical deadlock (and others) by supplying us with methods with which we may more thoroughly consider other experiential dimensions of theatre, the chief site of which is the process of its creation. I have seen how meaningful the process of intercultural work is for its participants, and postmodern ethnography makes that meaning available for further discussion.

29 There are early signs of a specifically postmodern (re)connection between theatre studies and ethnography. In an article about Singaporean director Ong Keng Sen’s 2000 production of Desdemona, Australian theatre scholar Helena Grehan engages with but moves beyond negative critical reactions to the play, choosing to write instead of her own experience while watching rehearsals of the performance that she writes "were breathtakingly beautiful as well as incredibly engaging" (117). Similarly, in a 2005 essay about the Journey to Con-Fusion project, Peter Eckersall productively analyzes representations in that project’s rehearsal exercises, taking into account the unique cultural positioning and perspectives of its collaborating companies. Grehan and Eckersall’s approach is perhaps more broadly semiotic than it is ethnographic, but the attention they give to process at least suggests an ethnographer’s interest in other experiential dimensions of theatrical creation. In the realm of theory, semiotics itself is still in the process of reconciling with poststructuralism. A recent issue of Semiotica concerning the present state of theatre semiotics features some discussion of how it might be further detached from a scientist or positivist tradition (see de Toro; Sidnell), together with suggestions for how it might be better used to open up communication across cultural difference (see Turner; Knowles). Knowles, in fact, suggests that semiotics might profitably draw on "other disciplinary approaches to performance analysis, including those such as the feminist, materialist, ethno-graphic, anthropological, and postcolonial" (236). I would add to this list approaches to performance in education, where ethnography has always had purchase, and where the negotiation of identity in creative processes has always been at issue. Anthony Jackson’s recent book Theatre, Education and the Making of Meanings, for example, profitably balances semiotic and ethnographic approaches to examine in specific contexts the relationship "between theatre’s aesthetic dimension and [its] utilitarian or instrumental role"(1).

30 A postmodern ethnographic approach will not be useful or practical for everyone, and it is not without its challenges. To begin with, it depends on the kind of access to (or even implication in) its subject that I enjoyed with my work on the PTMTP. It also has to balance the kind of individual voice and agency it promotes with the complex field of forces and scripts that issue from elsewhere within the performance text and the conditions of production and reception: the sponsoring institutions, the artistic facilitators of the project, the written materials which announce and promote the work, the audience’s horizon of expectations, the historical circumstances of a participating culture and the situatedness of the particular participants within those circumstances, and so on. Also worth considering is how ethnography may engage with new directions in semiotics, and not merely adopt what Kier Elam calls "closet semiotics," or a "hidden semiological agenda" (195). In any case, my aim here has not been to perfect a methodology. Like any methodology, the one I am proposing will have blind spots to match its strengths. My hope is that a postmodern ethnographic approach will add to the available interpretive toolkit without claiming any greater truth value than others and without becoming slave to its own rigid theoretical formations, and that it may help productively navigate the sometimes messy and confusing machinations of intercultural theatre.

Works Cited

Acker, Sandra. "In/out/Side: Positioning the Researcher in Feminist Qualitative Research." Resources for Feminist Research 28.3-4 (2001): 153-74.

The Art of Living. Program. Prague, Czech Republic: Ypsilon Theatre, 2004. Trans. Michal Schonberg.

Bennett, Susan. Theatre Audiences. London: Routledge, 1997.

Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. Routledge Classics. London: Routledge, 2004.

Bharucha, Rustom. The Politics of Cultural Practice: Thinking through Theatre in an Age of Globalization. London: Athlone, 2000.

Burian, Jarka M. Modern Czech Theatre: Reflector and Conscience of a Nation. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 2000.

Carlson, Marvin. "The Macaronic Stage." East of West: Cross-Cultural Performance and the Staging of Difference. Ed. Claire Sponsor and Xiaomei Chen. New York: Palgrave, 2000. 15-31.

Chaudhuri, Una. "The Future of the Hyphen: Interculturalism, Textuality, and the Difference Within." Interculturalism and Performance: Writings from PAJ. Ed. Bonnie Marranca. New York: PAJ, 1991. 192-207.

Clifford, James. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1988.

Clifford, James, and George E. Marcus, and School of American Research (Santa Fe N.M.). Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: U of California P, 1986.

Conquergood, Dwight. "Rethinking Ethnography: Towards a Critical Cultural Politics." Communication Monographs 58 (1991): 179-94.

David. Personal Interview. 3 July 2006.

de Toro, Fernando. "The End of Theatre Semiotics? A Symptom of an Epistemological Shift." Semiotica 168.1 (2008): 109-28.

Eckersall, Peter. "Theatrical Collaboration in the Age of Globalization: The Gekidan Kaitaisha-NYID Intercultural Collaboration Project." Diasporas and Interculturalism in Asian Performing Arts. Ed. Um Hae-kyung. London: Routledge-Curzon, 2005. 204-20.

Elam, Keir. The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

Esbach, Achim, and Walter A. Koch. A Plea for Cultural Semiotics. Bochum: N Brockmeyer, 1987.

Fine, Michelle. "Working the Hyphens: Reinventing the Self and Other in Qualitative Research." Handbook of Qualitative Research. Ed. N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1994. 70-82.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika. The Semiotics of Theater. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1992.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika, Josephine Riley, and Michael Gissenwehrer, eds. The Dramatic Touch of Difference: Theatre, Own and Foreign. Tubingen: Gunter Narr Verlag, 1990.

Freeman, Barry. "Cultural Meeting in Collaborative Intercultural Theatre: Collision and Convergence in the Prague-Toronto-Manitoulin Theatre Project." Collectives, Collaboration, and Devising. Ed. Bruce Barton. Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 2008. 217-30.

— . Unpublished Field Notes. Prague, Czech Republic. 2 May 2006

Gallagher, Kathleen. Drama Education in the Lives of Girls: Imagining Possibilities. Toronto: UTP, 2000.

— . The Theatre of Urban: Youth and Schooling in Dangerous Times. Toronto: UTP, 2007.

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. 2000 ed. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

Grehan, Helena. "Theatreworks’ Desdemona: Fusing Technology and Tradition." The Drama Review 45.3 (2001): 113-25.

Greenwood, Janinka. "Within a Third Space." Research in Drama Education 6.2 (2001): 193-205.

Hodge, Robert, and Gunther Kress. Social Semiotics. Cambridge: Polity, 1988.

Jackson, Tony. Theatre, Education and the Making of Meanings: Art or Instrument? New York: Manchester UP, 2007.

Katja. Personal Interview. 1 December 2007.

Knowles, Ric. "Vital Signs." Semiotica 168.1 (2008): 227-37.

Lather, Patricia Ann. "Issues of Validity in Openly Ideological Research: Between a Rock and a Soft Place." Interchange 17.4 (1986): 63-84.

Lather, Patricia Ann, and Christine A. Smithies. Troubling the Angels: Women Living with HIV/Aids. Boulder, Colo:Westview, 1997.

Lincoln,Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. "Ethics: The Failure of Positivist Science." Turning Points in Qualitative Research: Tying Knots in a Handkerchief. Ed. Yvonna S. Lincoln and Norman K. Denzin. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira, 2003. 219-37.

Lo, Jacqueline, and Helen Gilbert. "Toward a Topography of Cross-Cultural Theatre Praxis." The Drama Review 46.3 (2002): 31-53.

Lucy, Niall. Beyond Semiotics: Text, Culture and Technology. London: Continuum, 2001.

Melanie. Personal Interview. 2 June 2006.

Nicholson, Helen. Applied Drama: The Gift of Theatre. Theatre and Performance Practices. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Paula. Personal Interview. 2 June 2006.

Pavis, Patrice. Analyzing Performance: Theater, Dance, and Film. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2003.

— , ed. The Intercultural Performance Reader. London: Routledge, 1996.

— . Theatre at the Crossroads of Culture. London: Routledge, 1992.

Peterson, William. "Consuming the Asian Other in Singapore: Interculturalism in Theatreworks’ Desdamona." Theatre Research International 28.1 (2003): 79-95.

Polkinghorne, Donald E. "Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis." Qualitative Studies in Education 8.1 (1995): 5-23.

Shevtsova, Maria. "Sociocultural Analysis: National and Cross-cultural Performance." Theatre Research International 22.1 (1997): 4-18.

Sidnell, Michael J. "Semiotic Arts of Theatre." Semiotica 168.1 (2008): 11- 43.

Smith, Dorothy E. Writing the Social: Critique, Theory, and Investigations. Toronto: UTP, 1999.

Stake, Robert E. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1995.

Turner, Jane. "Dreams and Phantasms: Towards and Ethnoscenological Reading of the Intercultural Theatre Event." Semiotica 168.1 (2008): 143-68.

Veronika. Personal Interview. 10 June 2006.

Notes