Forum

Legion of Memory:

Performance at Branch 51

Melanie BennettYork University

Abstract

Legion of Memory is a site-specific performance co-created by Melanie Bennett and Andrew Houston, which was staged in an abandoned legion hall in downtown Kitchener, Ontario. Launched in June 2006 and remounted in April 2007, Legion of Memory attempts to animate the cultural displacement of the war veteran and refugee, while also exploring issues surrounding war memorials in Canada today.Résumé

Legion of Memory est un spectacle créé par Melanie Bennett et Andrew Houston dans une filiale abandonnée de la Légion, au centre-ville de Kitchener, en Ontario. Présenté pour la première fois en juin 2006 et repris en avril 2007, ce spectacle localisé cherche à illustrer le déplacement que vivent sur le plan culturel les anciens combattants et les réfugiés de guerre tout en explorant les enjeux actuels autour des monuments de guerre au Canada.

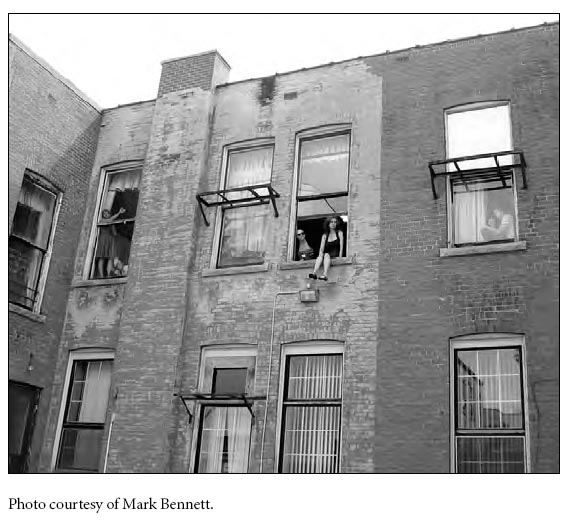

Display large image of Figure 1

1 Legion of Memory, a site-specific performance production co-created by Andrew Houston and myself, was originally launched in June 2006 for the Tapestry Festival, a multicultural event in Kitchener, Ontario. Because of its integration of a sophisticated soundscape developed by composer Nick Storring, the Kitchener Open Ears Festival of Music and Sound invited us to produce a remount for April 2007. Legion of Memory attempts to animate the cultural displacement of the veteran and refugee by having them meet in the abandoned legion hall, while also exploring the problem of war memorials in Canada today.

2 The following script is the remount version. Andrew Houston’s contribution was that of director, producer, and performer, and mine was that of scriptwriter, dramaturg, and performer. The overall project began as his brainchild, in which he invited me to participate as co-creator. As the devising process leading up to both productions included weeks of workshopping and improvisation, the performers—Brad Cook, Nicholas Cumming, Heather Hill, Viktorija Kovac, and Derek Lindman—were all noteworthy contributors to the development and revision of the narrative.

3 Perhaps the principal challenge of creating site-specific performances is securing a site. We hit the jackpot with Legion of Memory because the City of Kitchener welcomed the possibility of creating a show in the disused legion hall Branch 51 on Ontario Street North in Kitchener, Ontario. The City used our show as a launching event to promote Kitchener’s growing arts scene and to advertise the old legion hall as a possible rental venue for community artists.

4 All theatre is ephemeral, but the process-oriented method of site-specific performance makes it one of the most transient performance practices. Because the text and narrative of site-specific performance is drawn from the building and the objects found there, it is meant to be performed in the site of origin. With conventional theatre, the text tends to be considered sacred, whereas with site-specific work, the text is totally contingent upon what the site offers. If the show were to be staged elsewhere, the text would have to be altered considerably to accommodate the new site of performance.

5 It is a rare opportunity to be granted access to a disused building with all its original contents for two incarnations of a site-specific production, separated in time by over a year. Although the building was left in an almost identical state as it was for the original production, we utilized this unusual occasion for a remount to develop and evolve the show significantly from its original conception. One important change from the original version was the addition of interview excerpts with war veterans. These interviews were conducted by Andrew Houston and Brad Cook at a legion in Kitchener. In addition, a new soundscape was created by Nick Storring that juxtaposed these new interviews with the interviews of war refugees from Former Yugoslavia that we had used in the original launch version.

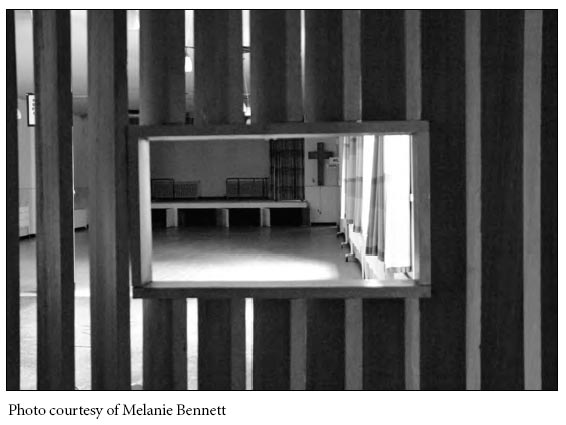

6 Another major revision to the remount performance was the addition of the Prologue, which was set in a couple of the lower-level rooms of the building. We were denied access to these rooms for the launch in 2006 due to the presence of asbestos and mould, but the City of Kitchener remedied the potentially hazardous situation by the time we were rehearsing the remount in 2007. One of the rooms we used was an empty chapel, which clearly resembled a chamber of mourning. We devised a series of ritualized gestures—of waiting, reflecting, and reaching out for help—that were performed by the refugee character played by Viktorija Kovac. We enhanced the atmosphere of mourning by including dozens of tea lights, a suitcase full of dolls, a smashed family photo, and a child’s musical wall hanging from Serbia.

7 The space surrounding the chapel resembled a dated administrative space that looked like it had been abandoned in a hurry. Unlike the completely vacant chapel, the office contained vestiges of an administration gone wrong. However, the office was also a place of mourning; it was littered with soiled letters, Remembrance Day posters, pension documents, photographs, memos, newspapers, maps, poppies, legion ribbons, a box of keys, and old Tim Hortons coffee cups. We started examining the discarded documents on the floor, and many of them referred to widows of veterans (and legion-naires) who were being denied benefits from the government. The letters were addressed to the Legion, which was being asked to back their claims for support. There were a lot of these letters, but there were also other kinds of complaints. From this we conceived the character of Lawrence Atchison, a name we created from the initials "L.A." engraved on an old discarded briefcase we found. Lawrence, performed in our production by Derek Lindman, is an accountant and descendant of one of the Legion members. In the play, he desperately tries to "account" for all of these forgotten complaints discarded on the floor. The office and chapel images, therefore, were juxtaposed with each other to become our Prologue. The addition of the Prologue set the stage for the legion "festivities," in that it offered a glimpse of both the legionnaire’s and refugee’s experiences of displacement and loss before the spectators were ushered upstairs.

Branch 51: A Peculiar Place for Refugees

8 During the 1990s, Kitchener became heavily populated with refugees from Former Yugoslavia. Many of them had escaped from their country because of the Yugoslav wars. These refugees had left behind lucrative work and family ties in order to come to Canada, a peaceful new home free from the daily threat of violence. Working from this background, we began to imagine how these victims of war would fit into a legion hall that honours those who fought in wars, but not those innocent victims caught in the crossfire. We wondered how these displaced individuals might meet in the space of this particular memorial, a building itself displaced by the passage of time and disuse.

9 As a fraternal organization consisting mainly of members drawn from the Canadian military (current and retired), the Royal Canadian Legion emulates an exclusive patriarchal men’s club, where a refugee’s presence may seem remarkably out of place. According to site-specific practitioner Mike Pearson, one of the aims of site-specific performance "is to construct something new out of old, to connect what may appear dissimilar in order to achieve new insights and understanding" (52). By deciding to have a war refugee from Former Yugoslavia enter a legion hall in the play, we created a new juxtaposition. The juxtaposition between the war refugees’ stories and the war veterans’ stories not only creates a remarkable picture of war and its larger effects, but a potential parallel between two very different groups of people. Both the veteran and refugee are happy to embrace a life free from war, yet both are also haunted by memories of a life damaged by it. Both are troubled by the disconnect between their "new" lives and their "old" lives. While the veteran seeks to erase the trauma by drinking at the legion hall, he also feels an obligation to memorialize the past by ensuring that war and the sacrifices required by it are not forgotten. Similarly, the refugee strives to forget a life ripped apart by war, yet there is a longing to preserve the memories of the family, career, history, and culture that have been left behind.

Animating Legion of Memory

10 As an emerging performance studies scholar, I am partial to creating work through a multi-faceted process, drawing on theories from various disciplines, such as cultural geography, archaeology, and performance art. Site-specific creation produces a rich and multidimensional performance practice that is infinite in its possibilities of transforming the spatiality of a site and the meaning of objects found within it.

Display large image of Figure 2

11 Mike Pearson defines site-specific performances as "conceived for, mounted within and conditioned by the particulars of found spaces, existing social situations or locations, both used and disused" (23). These performances rely upon the complex coexistence of a number of narratives and architectures, historical and contemporary. According to Pearson, there are two basic orders of site-specificity: "that which is of the site, its fixtures and fittings and that which is brought to the site, the performance and its scenography" (23). Here, the physical site (for example, a building) takes focus and provides an archaeological context for investigating a dense history. The material traces of the past found at the site determine the direction of the performance and result in an open-ended and non-linear form, reflecting the multiple meanings and valences that the site provides. Houston has described the methodology of site-specific performance as follows:You begin by seeing how the elements of the site (peeling walls, windows, staircases) are metaphors for the life experiences embedded in the site. This kind of work makes monologues and physical scores out of the broken floor tiles and searches for ghosts that inhabit a place in order to animate (using a variety of disciplines such as acting, dance, multi-media, etc.) the ghost’s story. (Houston, "Deep Mapping")While Houston is talking about site-specific performance in particular, his words point to broader ontologies of performance. In Cities of the Dead, for example, Joseph Roach argues that an important performance strategy "is to juxtapose living memory as restored behaviour against a historical archive of scripted records" (11). Roach is drawing on Richard Schechner’s idea that all performances are "restored behavior" or "twice-behaved behavior," by which he means behaviour that "is always subject to revision" (qtd. in Roach 3). Past performances must always be reinvented because they cannot happen the same way twice. All definitions assume performance functions as a substitute or "surrogate" for something else that precedes it.

12 Site-specific performance is an intricate blending of historical and contemporary detail that combines the myth, memory, and dream embedded in the host site. A variety of performance strategies—speech, images, gestures—supplement and contest the authority of archival documents in the historiographical tradition. When dealing with sites that are deeply embedded in historical discourse, the challenge for site-specific artists is to find the balance between knowledges of the past and our active engagement with the present. This creates a double narrative in which the performance "stands in for an elusive entity that it is not but that it must vainly aspire both to embody and to replace" (Roach 3). In trying to give voice to this double narrative, we thus move inexorably "between the absence of what we imagine the space to be and the material evidence of its proper and present uses" (Houston "Introduction" vii).

13 Legion of Memory is a complex overlay of the tangible myths that surround Branch 51 and its present non-use. Its meaning is constituted by histories of the people who might have occupied the building (war vets, women of the Ladies Auxiliary, building custodians, etc.), narratives taken from interviews conducted with refugees and war veterans in Kitchener, the artists’ responses to the site, and the spectators who complete the event as witnesses. Found objects also work to construct the site and its many resonances. The neglected building stores shrines dedicated to the fallen comrades of WWI and WWII; old documents outlining veterans’ pensions; newspaper clippings of significant events related to war, memorial, and legions; posters advertising dances; a Meat Draw board; soldier uniforms; and photographs.

14 As we looked through these objects of memory, we couldn’t help feeling the strong sense of nostalgia attached to them. The nostalgia found in Branch 51 created an atmosphere determined to distract its inhabitants from the threatening realities of war. Other evidence of the need for distraction was apparent in the form of records of celebrations: dances, games, and contests. The legion with its fossilized contents was the embodiment of a place of pause, evoking the sense of a time capsule; at the same time, it participated in narratives of national heroism that celebrated and romanticized war. The present anti-war sentiment stemming from the Iraq war made it necessary to create a performance that questions and revisits this discourse.While memorial performances often inspire nostalgia for authenticity and origin, the refugees in Legion of Memory transform the legion into a space of contestation. Suddenly, all the memorabilia glorifying war and demanding stasis come into conflict with the audible stories of refugees and their experiences of war’s unending reverberations. The objects memorializing the fallen comrades mark the absence of memorials for its other victims.

15 The first half of Legion of Memory follows what appears to be a traditional legion event. The MC invites the spectators to participate in the festivities. There is drinking, dancing, and a Remembrance Day ceremony performed by the veteran characters. Throughout these festivities, there are hints that indicate that everything is not as it seems. The 1940s music is slowed down, the dancing becomes violent, the drinking gets out of hand, the host seems a little sad. A sense of loss filters in through the soundscape of refugee and veteran narratives.

16 The nostalgia and sense of security surrounding the legion events are significantly disrupted halfway through the performance when a refugee character enters the building speaking Serbian on her cell phone. Her presence threatens the fantasy of the legion hall as a place of refuge, security, and stability. The refugee character is questioned by the Immigration and Refugee Board representatives. She is forced to dress as Slobodan Milosevic, covered with a UN flag, and interrogated. This scene uses excerpts from the transcripts of the Milosevic trial conducted by the United Nations court for its text. Juxtaposed with the trial is a tableau of one soldier being tortured, humiliated, and photographed by another soldier. The tableau recalls the 2004 accounts of the abuse and torture of prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq committed by members of the United States military. When placed within these contexts, the war memorial does not seem quite so heroic, nor do the politics of engaging in war seem so black and white.

17 While the publication of this script serves as an archive of loss, a record of the experiences of those whose lives have been altered by war, it is ultimately the spectator who ensures a living archive of these memories, carrying forward the ghosts unearthed in this ephemeral performance.