Forum

He Who Dreams:

Reflections on an Indigenous Life in Film1

Michael GreyeyesYork University

Abstract

This performative text was delivered by Michael Greyeyes as a keynote address at "Indigenous Film and Media in an International Context," a conference hosted by Wilfred Laurier University in association with York University in May 2007. The text examines a life in cinema through a post-colonial lens. Michael Greyeyes, an established screen actor and educator, explores the means by which native culture is constructed through media images and how indigenous performers resist, subvert and rewrite these constructions as part of their collective mandate to reclaim their own images and portrayals on screen.Résumé

Ce texte performatif a été livré par le conférencier Michael Greyeyes à Waterloo en mai 2007 lors d’un colloque sur le cinéma et les médias indigènes dans un contexte international organisé conjointement par l’Université Wilfrid Laurier et l’Université York. Greyeyes présente une vie au cinéma telle que vue à travers une lentille postcoloniale. Comédien de cinéma accompli et pédagogue, l’auteur explore les moyens par lesquels la culture autochtone est construite dans les images média et ceux par lesquels un performer indigène peut résister à cette construction, la subvertir et la réécrire. Tel serait en partie son mandat collectif: réclamer les images et les représentations de l'Autochtone au grand écran.The performer stood in front of a blank white screen upon which projections appeared. Throughout the address, the performer read aloud from several scripts, which included dialogue, stage directions, shot descriptions, etc. Stage directions for the keynote performance itself, which were not read aloud and which indicate the style of presentation, are here (italicized and placed in parentheses).

Greetings and Welcome Colleagues, Friends. Tansi and Boozhoo Filmmakers, Directors, Screenwriters, Critics, and Scholars. Hello Cineastes, Film junkies. (slyly) You know who you are. (beat) If a movie comes on at 2am—even if you’re dead tired—you’ll watch it all the way to the bitter end, all the way to the final fade out and credits! (Even if it’s terrible. Even if you’ve seen it before.)(sheepish AA first-timer) "Hi, my name is Michael. I’m a film addict."

(using various voices, overlapped): "Hi Michael. Hi, Mike." (Image: Writing appears on the screen, crisp white letters against black, "Hi, Michael.")

Ladies and Gentlemen. This is a map of a human heart. This is a chalk outline. These are footprints in the snow. . . leading to. . .

(reading from screenplay)

EXT. NIGHT.WINTER.

The air has a deadly chill. Lights from nearby houses and cottages cast an eerie glow through a stand of trees. THREE MEN are walking down a country road. The snow is hard-packed underfoot. Their breath comes churning out of their mouths. Their BOOTS SQUEAKING against the snow.

One of the MEN, a NATIVE man in his mid-twenties, motions the others to stop. He HEARS something. They all stop.

CLOSE ON NATIVE MAN.

NATIVE MAN

Do you hear that?

WIDE SHOT.

The other MEN shake their heads. The NATIVE MAN listens. He hears only winter silence.

NATIVE MAN

(shaking his head)

It’s gone.

They start walking again. Eager to get back inside to the warmth.

Sound of trees CRACKING in the wind. Likes bones breaking.

NATIVE MAN

That!

The other two MEN halt, again listening intently.

NATIVE MAN

Something’s out there. It’s following us. I can hear it when we’re walking. But when we stop.

It stops.

CUT TO:

POV from behind the trees. CAMERA dollies through the woods. The trunks of trees passing in front of the lens. Thick black rectangles moving right to left across the screen. The THREE MEN, not altogether unaware they are being watched, start walking quickly toward the house down the road.

Sound of bones BREAKING.

(end of screenplay)

The air was so cold and clear that night that the sound of our shoes hitting the hard-pack snow was echoing in the trees. . . Just our own footsteps bouncing off tree after tree. That’s all. . . It was better when I thought it was breaking bones.

(Image: Toronto, 1977. Except where noted, all subsequent text is white against a black background.)

National Ballet School. Maitland Street. Distorted mirrors and wooden floors.

(Image: "Indian Boy with Dancing Feet." Toronto Star.) "First Native boy, a Cree from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, accepted into Canada’s National Ballet School, after extensive auditions across Canada." Betty O. Broken bones.

Toronto, 1987. (Image: The National Ballet of Canada.) National Ballet. 70 Dancers. Full Orchestra. Powdered wigs. Frederick Ashton and Petipa. Fake moustaches and tambourines. Bones breaking. Swan Lake.

(Image: New York City, 1990.)

Breaking bones as I fell from the sky. Eliot Feld. July. So hot that I sweated through black leather ballet shoes. Leaving black footprints on the marley dance floor. Nancy. Walking hand in hand down 18th St., Astoria. Union Square. East Village. I saw Dances With Wolves on Broadway and 14th. Brown faces ten feet tall. Told her I wanted to be an actor. She didn’t bat an eyelash.

(Image: Los Angeles, 1993.)

Hollywood.

Franklin. The 101. La Cienega. Sepulveda. Burbank. Darryl Marshak. Harry Gold. First class airfare. Scripts arriving FED EX. Breaking bones.

"Slate myself?"

(using a woman’s tonality) "Yes, just look into the camera. Tell us your name and the part you’re reading for."

(some confidence, but still mostly tentative) "Hi, my name is Michael Greyeyes. I’m reading for the part of Red Cloud."

The image of the Indian is a site of contestation. Within this arena, theories of identity, racism, history, language, authenticity, essentialism, post-colonialism, etc. vie for dominance, each providing an entry point into the debate but none offering a complete picture of it.

Two recent documentaries: The Bronze Screen, an analysis of Latin actors in Hollywood, and The Slanted Screen, an examination of the experience of Asian actors, bring into focus the idea that our—and I am speaking as an actor of colour—our participation in an industry devoted to emptying us out, re-inscribing us as it sees fit is. . . problematic. That the cards are stacked against us. That the way out of the trap is to write, direct, and produce our own work. Subjectivity is the answer. This is, of course, right.

Taking the reigns, as it were, is a no-brainer. But being armed with a digital camera doesn’t make you accomplished. How do we develop the skill sets to make lasting work? The ability to create cinema and television that can change the world doesn’t usually spring from the womb. There is a system of training required. Some will call it programming, inculcation, indoctrination—but however you take it, whatever you name it, the training is needed before you have the right to call yourself a filmmaker, a writer. . . an actor.

You can’t walk onto the arena floor at Schemitzun and call yourself a dancer, just because you’ve got brown skin, black hair (under the breath), and a flat ass. I would think that you’d need to practice a bit, learn the songs, earn the right!?

Me? I had two systems of training: a conservatory model, with a good dose of on-the-job-training, and the classic indigenous model: mentorship. But we’ll talk more about that later on.

Okay, so you’ve got your diploma in hand, or experience under your belt. This isn’t your first barbecue. Before you run out the door, to "write, direct, and produce" your own work, I need to mention something. I don’t want to be a drag or bring you down, but let me play devil’s advocate for a moment. How are you going to get your film out there?

(encouraging) You’ve got the thing in the can. Great! I know how hard it was to raise the money. Believe me.A movie about indigenous people, made entirely by indigenous people. Hell. They probably wanted to give you ten dollars to go away!

(Image: Go away.)

Ahh, great! The film festival route is excellent. American Indian Film Festival in San Fran is a great place to start. Dreamkeeper! Fantastic. Sundance. South by Southwest. Cannes! Go for it. Shop it around.

(change of tone: ugly and condescending) Dress it up nice, while you’re at it! Put a wig on it, a nice pair of shoes. Redo the poster. Look you’ve got a hunk in the lead. Have him take his shirt off. Show off those pecs. That gorgeous brown skin! What’s the matter with you? What? It’s an art film? What does that mean? Lots of dialogue, no plot—that you want to lose money.

(Image: Hollywood-type.)

(strident, lecturing) This is a marketplace. We work on commission. . .

(beat)

(sudden change of tone, somewhat ashamed) I apologize. I didn’t mean to bring him out.

What I meant to bring up is that without distribution, the fine work of indigenous filmmakers—our hard-won subjectivity—will remain unseen, unheard. Without the imprimateur of studio distribution, I might never have seen, Once Were Warriors, Tsotsi, Rabbit-Proof Fence, Whale Rider, to name but a few international films.

No problem. Making the film is the hard part. (It is.) Distribution, by comparison, is cake.

Witness the much-heralded collaboration between Sherman Alexie and Chris Eyre, Smoke Signals. It was the darling of the festival film circuit. A Miramax film with all the trimmings. And it was ground-breaking. Indian characters were complex, fully problematized, and compelling. No white hero trope to bring a large-scale (read white) audience inside the story and our communities.

By 1999, Variety had announced that Miramax has signed a deal with Alexie to bring his own novel Reservation Blues to the screen. Months later—after swimming in the shark-infested waters—Sherman announced, "He was quitting the movie business" (Lyons). Reservation Blues replaced the forgiving tone of Smoke Signals with a more violent, angrier, and strident vision.When push came to shove, Miramax wanted no part of actual native subjectivity.

In an interview with The San Francisco Examiner, Alexie commented wryly,

There is a perception in Hollywood that "Smoke Signals" was a noble failure. . . In meetings I had, everyone had seen it, but the tone was, "I wish it would have done better." I always say that in the year it came out, it did better than "Pi," "Buffalo 66," and "The Slums of Beverly Hills" put together. It was easier to get $2 million to make "Smoke Signals" than $200,000 to make "Fancy Dancing." I couldn’t get anyone to give me $50,000. (qtd. in Curiel)

As a counter-move, Alexie—as big a name in the indigenous firmament as anyone—began making films on DV (his first The Business of Fancydancing) and seeking distribution outside of the major studio infrastructure. The move toward reflecting indigenous subjectivity within Hollywood remains a dream, despite promising press releases, "Indie" film awards, and public pronouncements to the contrary.

The control of the Indian image remains contested.

Given this reality, I propose that the work of native actors in mainstream films and television is akin to the work of undercover cops, like double-agents in a le Carré novel. Moles deep in the studio system, working from the inside.

"Hi, my name is Michael Greyeyes. I’m reading for the part of Crazy Horse."

This is the chalk outline of a native actor at the crossroads of internationalism, free trade, and false consciousness.What’s a Cree boy from the Qu’appelle Valley to do?

(Image: "We inherit whatever has been done by the previous generation." Tantoo Cardinal)

Ella Shohat and Robert Stam write that,

For [Donald] Bogle, the history of Black performance is one of battling against confining stereotypes and categories [. . .]. Thus subaltern performance encodes, often in sanitized, ambiguous ways, what [James C.] Scott calls "the hidden transcripts" of a subordinated group [. . .]. At their best, Black performances undercut stereotypes by individualizing the type, or slyly standing above it. [Furthermore], Bogle emphasizes the resilient imagination of Black performers obliged to play against script and studio intentions, their capacity to turn demeaning roles into resistant performance. (Shohat and Stam 195-96)

Breaking bones to fit into tight shoes.

This is a map of an actor’s heart. One man’s perspective; not typically myopic and narcissistic, we—as actors of colour—don’t have that luxury. We have burdens to carry. But it’s not all uphill. We have gifts too.

We have mentors. Trail cutters. Those who have walked before us. Into the deep drifts, so that we might journey more easily. This is a woefully incomplete list of previous generations of native performers, who opened, and in some cases, broke down doors for my generation.

Their names are:

Jay Silverheels, Chief Dan George, August Schellenberg, Tantoo Cardinal, Will Sampson, George Clutesi, Lois Red Elk, Gary Farmer, Denis Lacroix, Margo Kane, Gordon Tootoosis, Michael Horse, Jimmy Herman, Graeme Greene, Johnny Yes No, and many others.

Their contributions to changing cinema are perhaps not fully documented, but in time, should be recognized as analogous to the work that other performers of colour did for their own communities: Sessue Hayakawa, Paul Robeson, Dorothy Dandridge, Mako, Dolores Del Rio, and Sidney Poitier.

I am fortunate to have already worked with many of these aboriginal actors, and their role in my career development has been substantial and on-going. In fact, my relationship with three of them in particular—Schellenberg, Cardinal, and Lacroix—exemplify the benefits of emerging from within aboriginal culture and from a native acting community.

Foremost is that all three embrace their roles as mentors and teachers; just as they were taught, so, too have they taught in turn. August Schellenberg, for example, has taken me under his wing from the first film we worked on together. Within an hour of meeting him, Augie taught me how to hit a "mark" (back then, I didn’t even know what a mark was, let alone how to hit it) and shared with me his understanding of the differences between acting for stage and film.

They, in turn, were influenced by the previous generation, especially Chief Dan George. Lacroix recalls seeing Dan George, as Old Antoine, on Caribou Country:

I’d been to Lilloet and I remember the people from the bush [. . .]. I remember how they walked and talked. I says, "My God, they got this on film. Finally! They’re smiling, joking, their little asides, the physical way they relate to each other." And so much of the mannerism is still from the culture, the heritage, even though they may have gone to residential school. But you could see [. . .] from the parents to the children, you could still see it, you could still see the connection—closer to the grandparents. It wasn’t wiped out.

(Image: Resistance.)

Here, the expression of social dynamic—so often and dramatically absent in subsequent representations of native people—was a clear subversion by these native actors, revealing

(Image: Hidden transcripts.)

the "hidden transcripts" of that community, piggy-backed on radio waves into mainstream homes and minds.

These actors, friends, emerged as artists during the late 60s. This, of course, was the time of the revisionist Western. The time of Little Big Man and Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here.

It doesn’t take a Master’s degree to figure out that during this period, the Savage/Noble Indian was being emptied out—(full of ennui) again. Replaced this time by a radical deconstruction of the Indian image by writers and filmmakers from the counter-culture. But just as colonial America used the Indian in its search for a national identity, so too did Vietnam-era America seek to recast itself and invoke a hoped-for regeneration through the Indian symbol (Sandos and Burgess 112-14).

Resist the re-inscription. Subvert the stereotype. Restate the truth that was displaced by the stereotype.

Tantoo Cardinal:

What I’d do then is go back to my community, back to my experience, back to the women that raised me—the women I knew growing up. They’ve always been the inspiration for what I’ve done, and sometimes I would feel images that were coming from other places, that were not from the community. Constantly, you have to watch what’s been programmed (into you) before you even know that there was such a thing as programming.

The grammar of this re-inscription appears in many forms, the most common, of course, comes from "period" movies: the cultural misinformation, the stilted dialogue, the recycled—often inaccurate costumes, wigs, and war-paint. . .

(Image: Hollywood(en) Indian; note: the wood(en) portion of the text is bright red)

…the clichéd settings, the ponderous, solemn physicality, all of which has become accepted and unchallenged behaviour. This is the overt transcript that piggy-backed on radio waves to Poland, England, France, Australia, Korea, South Africa.

As if that wasn’t bad enough. These tropes have proven especially damaging when a native actor is unconsciously influenced by them. Lacroix notes, "People kept taking away from their strength, what made them. They dissolved it slowly, and it becomes like a ghost of themselves."

The tactics of subversion by native actors are numerous and sophisticated. A prime example of this is the action taken by the native cast, the cultural advisors, and even some of the non-native cast in changing the script for Bruce Beresford’s 1991 film Black Robe. Both Schellenberg and Cardinal remember turning down the project numerous times because of the script before finally accepting. Their reason for ultimately accepting was pragmatic: both actors knew that the film was going to be made with or without their participation and they believed it was better to allow their status and reputations to guide the film towards a more accurate representation, a decision prompted by the assurance of the filmmakers that key changes would be made before filming. This change on the part of the producers should be recognized as unique. Perhaps the discourse of resistance was more familiar to these filmmakers, who live in Australia where the aboriginal cultures are themselves involved in a very public struggle to recuperate elements of their culture. Or perhaps it was the willingness of the native cast, the cultural advisors and the entire community of background actors, to walk off the set if their contributions were ignored.

Clearly each instance of subversion must be weighed within the context of the project itself, but Lacroix, Cardinal, and Schellenberg all agree that it is vital to establish and protect dialogue as the principal means of opening the minds of the director, the writers, and the producers. It is there that a vital negotiation can take place, a negotiation that can drag an entire production, sometimes kicking and screaming, toward native subjectivity.

"Hi, my name is Michael Greyeyes. I’m auditioning for the role of Grey Eagle."

Making "period" movies is a tricky thing. First of all, it is an exercise in absurdity from morning till night. Even finding a place to film such a thing is problematic.

For example, where does one go to find untouched prairie nowadays? The pristine. Where do you find open prairie, without power lines and cell towers? Well, there is "open" prairie in the Dakotas and Montana, but it lies on gigantic ranches owned by a few powerful ranchers.

(Image: Robber barons.)

(increasingly furious and strident) As for being "untouched," one might easily argue the "owners" touched it alright. Stole it! If we can speak frankly, with their grubby pink little fingers, piece by piece.

(Image: Angry Indian-type.)

(beat, slow realization that the performer is caught up in the character again)

(ashamed, contrite) I apologize. I didn’t mean to bring him out. What I meant to bring up was that it was a beautiful morning, as we drove down a rutted road. And there were five tall, gorgeous tipis walking along a ridge. Like upside down ice-cream cones. (with romantic awe) The tipis were painted with striking geometric designs and pictographs, with their tops open and blackened by the smoke from many fires. (snapping out of it, an aside really) Yes, I said walking. Magically. . .

Actually, upon closer inspection, we could see about five pairs of feet inside each tipi, shuffling along. Talking to the crew later, I found out that that was the easiest way to transport the tipis from one filming location to the next. And, hey, you’ve got to have tipis!

Tipis and horses. If you’ve got Indians, you better have horses—even if none of the cast knows which end is which.

"My name is Michael Greyeyes. I’m reading for the part of Man Afraid of his Horses."

Pardon me?

Can I ride? (exhale derisively, then in arrogant, western-REZ-enese) Yeah, I can ride. I broke horses for a living.

(aside) This is not entirely a lie, as I used to drop miniature plastic horses down our toaster.

I had to learn how to ride horses for all the period films I did. My dance background helped me immensely. I became good at it. I remember we filmed a sequence where my character, Crazy Horse, was hunting buffalo. They herded a small group of buffalo (about twenty or so), which were meant to stand in for thousands.

(beat)

Imagine a prairie made black by their sheer numbers.

My blood was up. There were five cameras rolling on this shot. I had to ride bareback, shoot a bow and arrow, and control my horse, which was made extremely skittish by the buffalo. And everybody knows how unpredictable and ornery buffaloes are! Since it took about a half hour to round up the buffalo (they used pick-up trucks), every shot was doubly precious. My horse was a movie horse…. Let me explain. He knew all the calls that announced an upcoming shot: (shouted) "Quiet on the set." "Pictures up!" By the time they called "Rolling" or "Action," he was apoplectic and would nearly buck me off. They had to develop silent hand signals to announce "Action," etc., so we could get the shots we needed. His name was Whiskey. Playing Crazy Horse, for Turner Network Television, I rode a horse called Whiskey!

(right hand up, earnest expression, Scout’s Honour!) True story.

When the buffalo came over the edge, the stunt riders formed a phalanx around me, but it didn’t matter. My horse knew what to do, as if it was programmed for this. It flew across the prairie grass. Its speed was absolutely terrifying. When I let the reigns down on the horse’s neck to shoot my bow, it realized it was free and went into an even higher gear, an altogether and hitherto unimaginable speed. The horse tracked down one of the lead buffalo. I was riding next to it, fifteen feet away. I shot my arrow. It flew just inches above the animal’s back—just as I’d intended—burying itself deep into the soft ground near the cameras. The buffalo chase sequence lasted maybe 40 seconds.… It was the most intensely satisfyingly "Indian" experience I’d ever had. The other stunt riders were just as flushed as I was. We had recaptured something. Something authentic.

Later, I saw one of the Indian stuntmen, Scotty, one of the serious horse riders from around Browning, Montana fall to the ground during a shot. Something went wrong and a horse fell on top of him. Hundreds of pounds lying on him. The crew began to panic. He stayed completely calm, until the end of the shot. The horse was lifted off of him and he stood up, dusting himself off. I realized in that moment that this Indian man had a skill set—a way of knowing and acting—which I couldn’t even begin to approach.

The authenticity of my portrayal, my identity, fell away from me, like a rag.

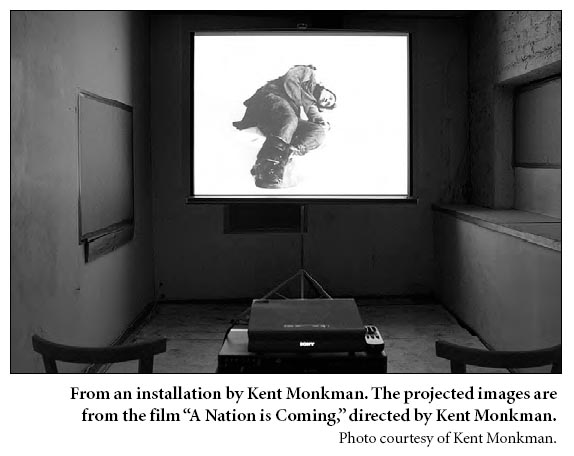

From an installation by Kent Monkman. The projected images are from the film "A Nation is Coming," directed by Kent Monkman.

Display large image of Figure 1

Rosemarie Bank, in her examination of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, described ethnographic re-enactment as "a conflation of real and faux." There is no better way to describe Indian period films. An uneasy mix of the authentic and the plastic.

Given their druthers, I don’t imagine many aboriginal filmmakers would make period films, but the studios still do. "The Western is cyclic. It comes and goes," they tell us. But conversely (and publicly unacknowledged) the historical Indian image doesn’t go anywhere. It has been commodified and entrenched within the Hollywood repertoire. Emptied out, re-inscribed. But at least as performers in these re-enactments, we are now co-writers in the event.

The continual process of re-inventing the Indian doesn’t only occur in the period films. The modern transformations are equally loaded with assumption, bald-faced ignorance, or simple wishful thinking.

"Hi, my name is Michael Greyeyes. I’m reading for the part of Thomas Harris."

In the audition rooms of L.A. (actually the hallways outside the casting office or in the parking lots), the group I affectionately refer to as the usual suspects congregate, trade information, gossip. It is here that our community is reformed—literally—outside of the studio gaze.

It was here one morning that Michael Horse was talking to me— mentoring me. He said,"Back in the 70s, it was me, Joe Running Fox, and a few others. We were the young guns then. And we’d meet out here too. You didn’t even have to read the breakdown, ’cause it was the same thing all the time. (beat) ‘Hey Joe, what’s the deal?’ (different voice, resigned) ‘Indian Radical protesting the desecration of ancient burial grounds—what else?!’"

(as Michael Horse nodding head)

Today, Michael Horse told me, it’s the same thing—just a slightly different setting. Now it’s all about Casinos. We’re lawyers, floor managers, bankers, tribal chairmen, heads of security, and we’re divided by it. Some of us want the Casinos. Some of us don’t. Does the mainstream public honestly believe that our internal discourse can be reduced to such a simple binary? I don’t know. Maybe they do.

"Hi, my name is Michael Greyeyes. I’m reading for the part of a slick, self-assured lawyer representing the interests of a wealthy, Casino-owning Tribal Nation."

This is an actual breakdown for a role I recently auditioned for.

The following contains meeting information for C.S.I: Miami:

Role: Reggie Vance

Late 30s/early 40s, NATIVE AMERICAN, ELEGANT Southwest attire, he’s the CEO of a Casino who’s being blackmailed by Scott O’Shay into being a silent partner in a major casino investment scheme. He is murdered by his wife, Adrian, after she discovers he’s been seeing the call girl, Anna Sivarro. . . GUEST STAR[;] Nan Dutton, Casting Director. (Mills)

When I read the breakdown to my wife, Nancy, she just shook her head. I got the part. In the end, though, they couldn’t meet my quote—my asking price. (blinks) Whatever that means. It’s one of the richest shows on television. Jerry Bruckheimer is one of the producers! They probably went Hispanic.

Which brings me to another point. How does this casting thing work exactly?

The American audience wants tall, lean Indians with brown faces and high cheekbones. Translation: Plains-types. Crees, Blackfeet, Crow, Lakota. This has been the case since the colonial period. The Plains cultures have always fired the imagination of the public: here, at home, and abroad.

A few years ago, I, and the usual suspects, auditioned for a film project called: "The Crow: Wicked Prayer," cast by Mackey/Sandrich Casting. The two leads were "native":

(reading)

Lily Ignites-The-Dawn, 21 years old, stunningly beautiful with raven black hair and radiant blue eyes, of mixed Native American, Hispanic, and European heritage [. . .] A traditionalist, Lily is disgusted by her father’s attempt to build an "Aztec Pyramid Resort Casino."

Tanner, Mid 20’s, Lily’s brother, Tanner is the local sheriff on the reservation, of Native American, Hispanic, and European heritage [. . .] (Casting Notice)

(blinks)

Nowhere in the script is there a reference to the mixed heritage of this supposed tribe, so for all intents and purposes, an audience will perceive this community as bona fide or "authentic." The filmmakers are having their cake and eating it too. They provide local colour to their film by bringing their audience to an exoticized locale and exotic, beautiful characters, but have the right to cast absolutely anyone in the roles of the Indians (Shohat and Stam 189-90).

The big problem with such casting is that non-native actors, with no vested interest in the depiction of this community—since they do not belong to it, nor have to return to it later to explain themselves—will allow their characterizations to be shaped wholesale by a writer or director. The burden of responsibility has been removed, and resistance to or even outright subversion of stereotypes has been compromised by the removal of native actors in native roles.

(reading from screenplay)

INT. DAY. CASTING OFFICE.

A self-absorbed director and pompous producer of "The Crow: Wicked Prayer" sit opposite a NATIVE man in his early thirties. A casting assistant operates a camera. The Los Angeles sunshine comes streaming through the window, casting a pleasant glow upon the proceedings.

DIRECTOR

So what did you think of the script?

NATIVE ACTOR

It was a piece of shit. (disbelief) Why? Did you think it was good?

The Director and the Producer looked shocked that the Native "talks back." They don’t know what to say.

CUT TO:

REALITY.

(end of screenplay)

I actually—and sadly—told them I loved the script. Wrong answer, even to them. They knew it was shit. Everybody knew. Acting is about speaking the truth—particularly when no one else dares to.

The authenticity of my identity—as an artist—fell away from me like a rag.

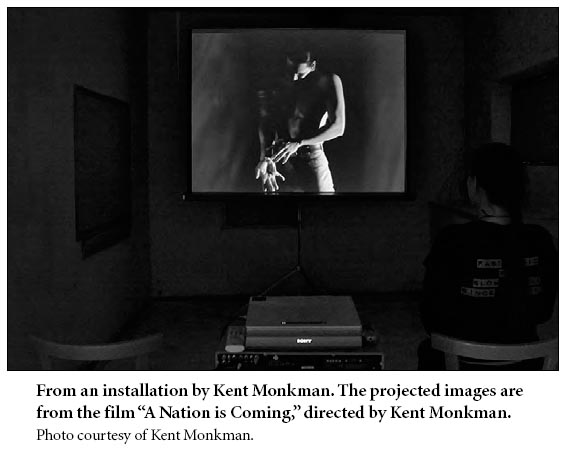

(Image: Artist, Monkman #3. This image remains until the end of the address.)

From an installation by Kent Monkman. The projected images are from the film "A Nation is Coming," directed by Kent Monkman.

Display large image of Figure 2

Well, it’s not all a drag. It’s fun, actually. And the money’s great.

The Chinese have a proverb about marriage, which holds true for the pay of the movie business. They say, "When you marry for money, you earn it."

But. . . there is a tremendous nobility to our roles as performers.

We join a long line of resistance fighters:

deflecting or absorbing prejudice. . .

(with growing intensity and vigour)

subverting misguided intentions,

or encoding our performances with our "hidden transcripts."

So that when these images come across your televisions or grace the screens of your movie houses, the site of the Indian remains hotly contested. And we neither give, nor take any quarter.

"Hi, my name is Michael Greyeyes. I’m reading for the part of. . ."

(The performer takes a single step back, away from the podium, now framed fully by the image on the screen.)

Works Cited

Bank, Rosemarie. "Representing History: Performing the Columbian Exposition." Theatre Journal 54.4 (2002): 589-606. 3 April 2007 http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?url_ver=Z39.82004&res_dat=xri:iipa:&rft_dat=xri:iipa:article:citation:iipa00216065.

Cardinal, Tantoo. Personal Interview. 5 January 2003.

Casting Notice for The Crow: Wicked Prayer. 31 January 2003. 8 February 2003 http://www.breakdownservices.com.

Curiel, Jonathan. "‘Fancydancing’ Was Struggle for Duo from ‘Smoke Signals’: Adams,Alexie Found Little Support in Hollywood." The San Francisco Chronicle 31 August 2002: D1.

Eyre, Chris. Smoke Signals. Los Angeles: Miramax Home Entertainment, 1997.

Horse, Michael. Personal Conversation. February 1996.

Lacroix, Denis. Personal Interview. 4 January 2003.

Lyons, Charles. "Alexie to Make Book at M’max." Daily Variety 10 December 1999: 1.

Mills,Alan. "Self o[n] tape for: Michael Greyeyes - CSI: Miami." Email to the author. 5 February 2007.

Sandos, James A., and Larry E. Burgess. "The Hollywood Indian versus Native Americans: Tell Them Willy Boy Is Here (1969)." Hollywood’s Indian: The Portrayal of the Native American in Film. Ed. Peter C. Rollins and John E. O’Connor. Lexington: U of Kentucky P, 1998. 107-20.

Schellenberg, August. Personal Interview. 5 January 2003.

"Sherman Leaving Hollywood." Indianz.com. 23 June 2000. 10 October 2002 http://www.indianz.com/News/show.asp?ID=lead/6232000.

Shohat, Ella and Robert Stam. Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Notes