Articles

Project [Murmur] and the Performativity of Space

Chris EaketCarleton University

Abstract

In The Practice of Everyday Life, Michel de Certeau asserts that "what the map cuts up, the story cuts across" (129), stressing the role of a nomadic, storytelling subject in the production of space. The [murmur] project, an experiment in site-specific psychogeography and cybercartography (http://murmurtoronto.ca), explores the relationship between spaces represented cartographically, spaces lived through audience explorations, and the (imaginary) representational spaces generated through oral histories. The site-specific stories of participants, delivered by cell phone to audience members at specially marked sites, transform reified places into lived spaces that the user can explore and interpret in real time. [murmur] situates the subject simultaneously at the site of the referent and within an imaginary (aural) space of representation, compelling the audience member to reconcile the two. In exploring the representational frame (and its boundaries), the user becomes an active participant in the semiotic processes of spatial production. Thus, [murmur] can be seen as an important intervention: rather than accepting the reified city as a given, or acting on the subject in a way that limits semiosis, the places the project constructs through discourse encourage the emergence (or becoming) of a nomadic subject who produces new meanings through a process of spatial dialectics. Equally important, [murmur] foregrounds the need to rethink cities not as sets of buildings and objects, but rather as places where historical and subjective information is latent in every materiality and, similarly, where the materiality of city is seen as the result of the performative processes of spatial production.Résumé

Dans L’invention du quotidien, Michel de Certeau écrit que « là où la carte découpe, le récit traverse » (190), mettant ainsi en relief le rôle du narrateur nomade dans la production de l’espace. Le projet [murmur], une exploration de la psycho-géographie et de la cybercartographie localisées (http://murmurtoronto.ca), s’intéresse au rapport qu’entretiennent les espaces représentés par cartographie, ceux dans lesquels circulent un auditoire et les espaces représentatifs (imaginaires) créés par l’histoire orale. Les récits localisés que livrent les participants par téléphone cellulaire aux membres du public dans des sites signalés transforment des lieux réifiés en espaces vécus que l’utilisateur peut explorer et interpréter en temps réel. [murmur] inscrit le sujet à la fois dans le site du référent et au cœur d’un espace de représentation (sonore) imaginé tout en invitant le public à réconcilier les deux espaces. En explorant le cadre représentationnel (et ses frontières), l’utilisateur participe activement aux processus sémiotiques de la production spatiale. Ainsi, on peut dire de [murmur] qu’il s’agit d’une intervention importante : au lieu d’accepter la ville réifiée telle qu’elle est ou d’agir sur le sujet de façon à limiter la sémiose, les espaces que construit ce projet par son discours encouragent l’émergence (ou le « devenir ») d’un sujet nomade qui produit de nouveaux sens par une dialectique de l’espace. De façon tout aussi importante, [murmur] souligne qu’il faut repenser la ville non plus comme un ensemble d’édifices et d’objets, mais comme un lieu où circulent des renseignements historiques et subjectifs présents de façon latente dans tous les matériaux. De même, la matérialité de la ville serait conçue comme le résultat des processus performatifs de la production spatiale.1 "Where are you right now?" It is one of the most common questions one is asked when using a cell phone. "Where are you" has become a mantra of the mobile age, according to Sadie Plant (29), in an attempt to fix conceptually the disembodied voice in a particular space and time, and to "set the scene" of our discourse. Contrary to early notions of digital technologies enabling some sort of incorporeal virtual ether, a "sense of place" and situated knowledges are gradually reasserting themselves in technological discourse (see Haraway; Ryan, Marie-Laure). As Marie-Laure Ryan remarks, the "seemingly straight trajectory leading out of the constraints of real space into the freedom of virtual space is now beginning to curve back upon itself, as the text rediscovers its roots in real world geography." One result of this renewed sense of place is the proliferation of site-specific, narrative artworks that combine storytelling, performance, and locative technologies to produce new forms of street theatre.

2 [murmur], a Toronto-based storytelling project that uses cell phones to deliver narratives to audience members at specific local sites, exemplifies some of the main strategies and concerns of these new hybrid artists, and provides a jumping-off point for a discussion of the theoretical implications of this innovative form of performance. The [murmur] project lies at the intersection of several different cultural movements that continue to influence its development: the proliferation of technologies such as cell phones, GPS, PDAs, and wi-fi, and their deployment in locative media art; site-specific performance and its dependence on the interactive spectator; Situationism and non-functionalist discourses of the city; and the still-emergent "spatial turn" in cultural studies and the humanities.

3 Locative media and site-specific performance emerge out of very different disciplines, yet share a common emphasis on place and context as major determining factors in the construction of meaning. "Locative media" is a catch-all term coined by Karlis Kalnins for a set of new media practices that explore the interaction between data networks and the physical space of the urban environment. According to Drew Hemment, AHRB Research Fellow in Creative Technologies at the University of Salford, "locative media uses portable, networked, location-aware computing devices for user-led mapping and artistic interventions in which geographical space becomes its canvas." In a sense, locative media is what happens when street theatre meets the wireless Internet; it is an effect of information being available anywhere, anytime in the built environment. In the case of [murmur], the cell phone provides the interface for overlaying the city with hypertext-like audio content.

4 "Locative is a case, not a place," Kalnins says, meaning it is a form that unfolds in space, as well as time, providing an experience that can only be understood after the fact, as a whole (Rushkoff). This is distinct from traditional functionalist uses of maps and location-based data, where one is concerned with how geographic points allow us to achieve some spatial objective. The pervasive nature of locative technologies allows new narratives to be told by fixing data to places and adding time-based elements to spatial trajectories.

5 Site-specific performance shares this concern with overlaying meaning on places but, rather than emerging from the discourses of computing and GPS/GIS, grows out of traditional theatre practices (particularly in the UK). Nick Kaye’s groundbreaking work, Site-Specific Art, outlines a set of practices that constitute a "working over of the production, definition and performance of ‘place’" (3). Site-specificity emphasizes a contextualized framing of place that implicates the viewer as a co-creator of meaning at all times. Rooted in traditions of Conceptual Art, Environmental Art, and Street Theatre, one of the main tenets of Site-Specific Art is, following Richard Serra, "to move the work is to destroy the work" (qtd. in Kaye 2). To move the work is to replace it or make it into something else; the discursive exchange with the environment that constitutes the artwork’s intended meaning is irrevocably lost if it is re-contextualized. Kaye remarks that these site-specific practices are intended to "articulate exchanges between the work of art and the places in which its meanings are defined." Furthermore, "[i]f one accepts that the meanings of utterances, actions and events are affected by their‘local position,’ by the situation of which they are a part, then a work of art, too, will be defined in relation to its place and position" (1). As a rich tradition of place-based performance, site-specific art is perfectly complemented by locative media practices and technologies. The pervasiveness of locative media technologies, such as wireless internet, webcams, mobile phones, and satellite GPS, means that any location becomes a potential ur-place for site-specific art; given the embodied subject and his/her recording media, any site can take on meaning as a collection of readable, remixable, and deployable signs.

6 As McLuhan predicted in 1968, the immersion of subjects in a total media environment constructs a perception of the built environment as a sort of "programmed happening" (113) or series of "pseudo-events" (122). The pervasiveness of locative technologies is constructing exactly such an environment. Locative media technologies and site-specific performance combine to produce artworks such as [murmur] that reveal the built environment as a particular kind of theatrum mundi that is continuously, performatively produced.

7 The myriad of concerns that [murmur] deals with, including place, technology, the built environment, and performance, are largely a result of its origins and the diverse interests of its creators. The [murmur] project was originally designed as a final project in the Interactive Art and Entertainment Program at Habitat, the Canadian Film Centre New Media Lab. The last four months of the program are dedicated to teams working on the production of working prototypes. The three collaborators on [murmur], Shawn Micallef, Gabe Sawhney, and James Roussel, were drawn together through an interest in the city, its history and stories. Given the group’s diverse backgrounds, this combination makes sense: Micallef has an MA in political science and works as a freelance writer, Sawhney studied architecture and works as a web designer, and Roussel writes and acts in Toronto (Alderman). "The idea for [murmur] grew organically, but was firmly rooted in the strong feelings the three of us have for the city, and the agreement that a computer screen is just too far from the street to have any real emotional impact when talking about the city," remarks Sawhney (qtd. in O’Donovan). Unlike their other colleagues at Habitat, the three wanted to do neither a film-based project, nor a website. "We wanted to do something that could pop up in people’s everyday lives, that they could experience easily," Micallef recalls (qtd. in Whyte).

8 The use of cell phones was a pragmatic choice, despite their limitations: "Telling location-based stories using cell phones seemed to be the best way to get all these stories out to the most people in the spot that they happened. Not everybody has a cell phone, but it was the delivery device that could reach the most amount of people" (Rossi). Similarly, Roussel sees the project as a way of altering our thinking about cell phones away from being "an irritant" towards being "a very personal portal into something that is very significant" (qtd. in Toman). The group designed [murmur] to be a public art intervention in the built environment, one that "connects people with their city by allowing them to listen to stories about particular locations while standing in those places. People walking past these sites notice a sign which indicates the presence of a story and provides a number they can dial using their cellular phone" (O’Donovan). The stories are told to pedestrians specifically since one of the aims of the project is to get people to relate to their city and community members at street level (Bowness).

9 What is interesting here is the attempt to collapse social distance through the intimacies of storytelling, using a technology commonly thought of as a device of extreme mediation. Ironically, while despatializing technologies such as the cell phone have collapsed geographic barriers to communication, they have not necessarily decreased social distance; in fact, the opposite is more often the case: "Economic communications and financial empires tell us that place is less important for communication,[but place] is becoming more important to people" (Hunter 144-45). In the case of [murmur], the personal, local stories delivered to cell phones decrease social distance while emphasizing individual attachments to places; in doing so, [murmur] works performatively to produce a vibrant neighbourhood overcoded with meaning.

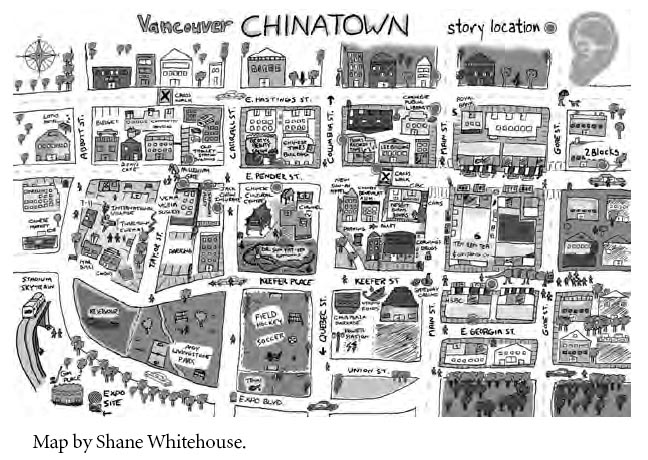

10 The response to [murmur] was positive from its early demo version at Habitat, and the group was encouraged to do a larger-scale launch. In 2003, the collective launched a version in Kensington market with 29 signs and associated stories. The group then developed city-specific [murmur] projects for Vancouver and Montreal, and, with funding from municipal and provincial arts councils, expanded to the Annex and Spadina Avenue between Davenport and Wellington Streets in Toronto. Pieces were developed for the Drake Hotel and inside Hart House, and more recently the group has again expanded to the area around Yonge and Dundas Square (Ryan, Carol-Ann). The group’s website at murmurtoronto.ca provides a desktop version of the [murmur] stories, complete with hand-drawn maps and links to audio clips. (All subsequent audio clips, referred to by number in this paper, can be found on this website.) The collective has also set up [murmur] sites in San Jose, California and had inquiries from various countries in Europe: "In Europe, there have been a bunch of projects that are basically talking plaques, and they are as dull as you would expect them to be. But what we have is appreciation of storytelling, an appreciation of voices" (Sawhney, qtd. in Whyte). A view from below that is multi-perspectival and counter-hegemonic is clearly important to the [murmur] collaborators: "We’re trying to give equal weight to everyone’s story, whether they’re regular people, or the ruling class, which is usually the traditional history of Toronto the Good" (Whyte). In this sense, the telling of stories becomes a form of community ownership, a claiming of space and history that is democratic and polyvocal, rather than unified and authoritative.

Display large image of Figure 1

11 In the interest of increasing a sense of community ownership, [murmur] has been experimenting with allowing users to record their stories using their cell phones, instead of having users come into a studio to record their tales (Alderman). Furthermore, the group plans to eventually hand over editorial control to the communities in which the project exists: "we’d like to set up an editorial board made up of community members, much like a newspaper editorial board, who will help us ensure whatever personal innate biases we might have do not skew story selection in a particular direction," says Micallef (qtd. in O’Donovan). Such a selection process would ensure that the univocal history of "Toronto the Good" is not replaced by that of [murmur], allowing the communities themselves to define who they are through the stories they tell.

12 The street-level approach of [murmur] means that many pedestrians merely stumble across the project in the course of their daily activities. One journalist’s chance encounter with [murmur] is here quoted at length, to give the reader an idea of what this experience is like:In Kensington Market, at midnight, I am looking at a small, square, green sign with a white border. The border bleeds and twists into the word "Murmur." A phone number, 416-915-6877, is neatly typed in the centre of the square, just above a six-digit number. As a detective, I have but one course of action. I must investigate. I dial and wait."This is Murmur, what’s the code?" A code! Of course! The six-digit number on the sign is a code! I am alive with questions and suspicions. [. . .] And the strangest thing happens. A man’s voice begins to tell a story about the house in front of me. "A few years ago at 30 Kensington, where I lived, my daughter met me in the morning and said, ‘I had the weirdest experience.’"I attempt to interrupt, "Excuse me," but the narrator continues. He speaks of ghostly child visitors, an accidental discovery and a surprising realization. He has offered me a personal memory—a homemade patch of Toronto history. (Loureno)The surprise of receiving a subjective and personal recollection that affectively connects us to places is part of what the project is all about. Micallef explains, "You may not have anything to do with the story but once these narratives are layered on a different patch of the city people feel more invested in the place they live, and also those strangers that you pass don’t seem so strange anymore. It’s just a sense of knowing the stories of your community"(qtd. in Rossi).

13 The multiple perspectives of the audio monologues represent a Bakhtinian polyphony of discourses: some nostalgic, others amusing, still others historical or deeply personal. Opposed to the "God’s eye view" of traditional maps and histories, [murmur] emphasizes what Haraway calls embodied or situated knowledges. This is not a view from above, but rather the multi-perspectival, crowded, and jostling viewpoint at the level of street. The project shares audio-historiographies specific to certain subjects in a particular time and place, as opposed to the "authoritative" and unified history of the audio-enabled museum. As Micallef notes, "It’s not the official voice of Toronto. It’s just every voice" (Underwood). Roussel remarks that "what makes it dramatic is that it’s not some voice actor. To hear someone actually kinda stutter and be real, that’s how people actually talk. There’s an accessibility there" (qtd. in Toman). Further, [murmur]’s Sawhney notes that "We really want to hear accents. Accents are one of our favourite things, because they help differentiate perspectives and experiences" (qtd. in Whyte). The situated knowledges embodied in accents and discourses produce something that is paradoxically more Other, but also more realistic, personal, and engaging due to its specificity. The multi-perspectival viewpoint of street-level pedestrian culture is represented through the many voices of the storytellers, in all their verbal distinctiveness.

14 The site-specific stories of community dwellers, delivered by cell phone to an audience, transform reified spaces into "lived" social places of collective memory, folklore, and affect. As Micallef remarks, "People ignore a lot of stuff in our surroundings, but once you lay a narrative on it, it becomes a place. You might dislike the story but you can’t ignore it" (qtd. in Perlman). The space/place dialectic, analyzed by de Certeau in The Practice of Everyday Life, sees the notion of space as topographical, fixed, and cartographic, whereas place is discursive and contextually fluid, having its basis in social practices and relationships (117-20). Part of what [murmur] attempts to do is ensure that for audiences, "the smallest, greyest or most nondescript building can be transformed by the stories that live in it. Once heard, these stories can change the way people think about that place and the city at large" (Micallef, Sawhney, and Roussel). Transforming spaces—by "changing how people think" about the city— into "activated" social places, the project reveals the embedded socio-historical meanings and contingencies of materiality. A conscious awareness of the built environment’s contextual, social, and historical dimensions in turn produces a subject that is able to imagine the city otherwise. As one user remarks, "After an afternoon of listening to the Green Ears, the truth hit me. [My city’s] great strength lies not in its population or skyline or riches, but in its incredible wealth of stories" (Herhold). This shift in audience perception away from the physical city, towards an appreciation of the city as something inherently narrative, is quite remarkable. The semiotic notion of the city as a discourse (Barthes 92) is clearly evident here and this is exactly the experience that [murmur] provides.

15 The performance of these oral histories over cell phone means that "the user is free to wander throughout the space, touching the objects and structures described in the story" (O’Donovan). In this, the project exemplifies what Nick Kaye sees as one of the defining features of site-specificity: "a working over [. . .], a restlessness arising in an upsetting of the opposition between ‘ideal’ and ‘real’ space"—that is, a problematization of the relationship between the socio-cultural sign and material referent. "Furthermore," Kaye continues, "in upsetting or deconstructing these oppositions, site-specificity is intimately tied to notions of event and performance" (46). Or as [murmur]’s Micallef remarks, "Hearing a story in the space where it happened lets you feel the story and reconcile it with what you see and feel around you" (qtd. in Bowness).

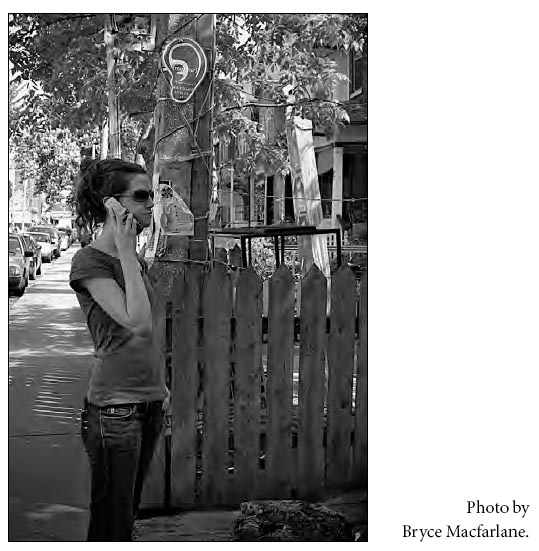

Display large image of Figure 2

16 In one example from [murmur], a storyteller remembers a bar that once existed at 169 Augusta:So, 169 Augusta [. . .] the Lobster Island Seafood Company—a wonderful place to acquire lobster— but you know it wasn’t always Lobster Island; it was this place called the Sibony Club, which was sort of an after-hours dive bar kind of thing. [. . .] The good thing was there would be all sorts of different things, like one night there’d be a band, another night there’d be some sort of avant-garde theatre thing, one night some lesbian poets and Frisbee throwing—so it housed a really nice variance. [. . .] It was a great little place and I don’t know what happened to it [. . .] (Kensington Market #214618: Timber Masterson)The listener is forced to reconcile the material referent of Lobster Island with the description and signs of the Sibony Club. Such an approach implicates the viewers as co-creators of meaning by having them reconcile the two versions of the same place. The aim is to have the audience "work over" these overlapping historical moments until they resolve into a new synthesis: an appreciation of place that is both material and historical, as well as deeply social. The performance of place reveals "lived realities as practiced," integrating a site’s materiality and conceptual content with its social dimension and historiography (Soja 10).

17 [murmur] relates the collective memory of the city and relies on memory to construct an imaginary mise en scène that is relatively complete. It is a curious reworking of the ars memoria, a mnemonic technique whereby "memory places" were constructed and designed to aid in the organization and recall of oratorical scripts (Yates 18-19). In this case, however, we walk through someone else’s "memory place," digitally reproduced and transmitted via cell phone. Some places, such as the Sibony Club, now exist only as a "memory place." With each rhetorical performance, however, it is reconstituted through language, reconstructed as an imagined mise en scène for the listener. As [murmur] collaborator Gabe Sawhney says, "I love it when I hear that someone listened to a story about a shop/bar/building/whatever, which is gone now, and they’d forgotten about [. . .] but had a flood of memories rush back when they heard the story" (Alderman).

18 So how does this work as a site-specific performance? The first performance—that of the disembodied storyteller on the phone—is akin to the auditory mimesis of radio drama, whereby aural descriptions construct an imaginary mise en scène and its characters. This form demands the active participation of the listener to fill in the gaps or concretize the scene in terms of reception; the audience member draws upon previous experiences and images in order to conjure an imaginary scene that is relatively complete (Beck 1).

19 But what of our listener, standing in front of a building with a cell phone pressed to his/her ear, attempting to reconcile these real and imagined spaces? The slippage between the site-as-referent and the audible signs that constitute the mise en scène demands active participation—indeed, an active performance on the part of the audience member. Going beyond the participatory "filling in the gaps" of radio drama, here the audience member is actually interpellated into the "programmed happening," both at the level of site-as-set and as an active interpreter of and participant in the production of signs. Interpellation, a term from Marxist media theory, denotes both the positioning of the audience within a preexisting structure and their constitution as subjects, building as it does on Althusser’s original notion of subjectivization (Lapsley and Westlake 12).

20 The aural nature of the descriptions on the cell phone affects what McLuhan calls the "allatonceness" of auditory experience that surrounds and permeates the listener, in opposition to the single, dominant perspective of visual gaze (McLuhan 116-17). "By using a mobile phone," remark the [murmur] collaborators, "users are able to listen to the story of that place while engaging in the physical experience of being there" (Micallef, Sawhney, and Roussel). While the interpellation of the audience/subject into the auditory mise en scène may confound our typical notions of audience and performer, Brenda Laurel notes (in her provocative book Computers as Theatre), that "feel[ing] yourself participating in the ongoing action of the representation," is one of the hallmarks of interactivity (20-21). This means the audience participates in the action from within the representational frame. The auditory mise en scène, like the theatrical stage (or the GUI interface), places actors/agents in a zone where they themselves are being socially constructed while constructing meaning; the subject is active in the performative production of space, while performing within the limits of the mimetic frame.

21 The audience-participant necessarily engages with the social practices, speech acts, and discursive practices that performatively produce the built environment as it is experienced. The socio-historical dimension extends our experience of the city to give it historical depth; by experiencing the city as a series of moments and memories, one gains an appreciation for how it has been performatively produced, constructed, and experienced over time. If we think of the city as merely physical, a static and given topography devoid of the practices of power/knowledge, we risk overlooking the historical, discursive, and social practices that actively produce it. As Butler remarks, performativity should lead us toa return to the notion of matter, not as site or surface, but as a process of materialization that stabilizes over time to produce the effect of boundary, fixity, and surface we call matter. That matter is always materialized has, I think, to be thought in relation to the productive and, indeed, materializing effects of regulatory power in the Foucaultian sense. [. . .] And how is it that treating [. . .] materiality [. . .] as a given presupposes and consolidates the normative conditions of its own emergence? (9-10; emphasis in original)Performativity in/of the built environment means the interrogation, reworking,and iterative deployment of signs and practices; in doing so, we discover that the city is not so much a normative set of objects, but rather has been discursively produced over time through a process of iterative citationality of the normative "city" (see Derrida, Limited; and "Signature"). More often than not, this normative "city" exists through the maps of city planners and not based on the symbolic, cultural, experiential, and social needs of its citizens. James Roussel, Art Director for [murmur], remarks that "what we’re trying to do is to build an entire, opposite, one-[of-]a-kind, popular mythology of a city at a citizen level. It’s something that’s never been done, and that’s what people crave" (qtd. in Toman).

22 The performativity of space can then be understood as the "acting-out" of a place through social practices, specifically actions and utterances, that contextually and through repetition determine its functional meaning within a meshwork of social habitus. It is an engagement with the site/referent as a limit case—a line we can approach but with which we can never intersect—where iterative speech acts attempt to approximate the ontological status of a place. Instead of a singular perspective, what is revealed is an archaeology of difference, a multiplicity of ontological strata, which exposes any single authoritative claim to be only a sedimentary illusion of fixity.

23 The idea of the site as a multiplicity, as a set of historical and experiential strata that define what a place "is," is exemplified by the audio entries outside Fresh Baked Goods at 274 Augusta:PETE PELISEK. I was walking home down Augustana towards College Ave. It was about three or four in the morning. [. . .] Across the street on the other side of College I see a deer run by. I had never actually in my life seen a deer of the wild before [. . .]

LAURA JEAN THE KNITTING QUEEN. And so I thought this guy probably likes me. At that point I didn’t realize it would be five years later and he would have joined my company and we’d be working together...and we’d be engaged at La Palette just down the street and be married.

JACLYN. I ended up talking to him [. . .] and he said, "but we won’t need sweaters soon." And I said, "Oh, why won’t we need sweaters?" "Well we won’t need sweaters when the gates of heaven open." [. . .] And I was thinking, "alright, I’d better wrap this up..." (Kensington Market #232626)

These are three entirely different experiences, with widely varying effects, that are tied together by their spatial location. In turn, these speakers are revealed to be connected to each other through the places they frequent and have strong connections to; as listeners, our identification (or disidentification) with these speakers and their stories shapes our appreciation of a place and connects us to a historical signifying chain that is grounded in the embodied experience of a spatial location.

24 The embodied and lived experience of the city is part of the social axis of urbanism that [murmur] attempts to trace through memories and folktales. It is the element that distinguishes a congenial "neighbourhood" from a set of buildings and escapes signification in traditional, objective mapping systems. Its basis in subjective relations means that it overlaps Benedict Anderson’s notion of an "imagined community," or a collective social imaginary with which we seek to identify or which we discursively oppose. As Anderson notes, the size of modern communities usually means that "members [. . .] will never know most of their fellow members [. . .] yet in the minds of each lies the image of their communion" (6). Through newspapers, books, and other forms of widely distributed mass media, the ability to create a social imaginary becomes possible for large populations and geographies. This process is accelerated and complicated by electronic culture, in which multiple identifications are possible and where mass-mediated imagination is now part of the fabric of everyday experience. "[I]magination has broken out of the special expressive space of art, myth, and ritual," remarks Appadurai; it has been incorporated into the images, models, and narratives of global media to become part of "the logic of ordinary life"— a logic which also includes the various social scripts that constitute identity (5).

25 Different from fantasy in that it holds the promise of ideation and sociality (and therefore collective action), imagined communities are often the first step in creating actual communities of shared values and affect (Appadurai 7). Or as [murmur]’s Micallef remarks,"[we’re] selling you your neighbours."Instead of advertising, [murmur]’s stories are"actually information you want to hear. It’s bubbling up through sidewalks—selling you not more stuff,but experiences and people" (qtd. in Pugh). The project’s stories use locative media to create an imagined community at the local level, in order to iteratively actualize a neighbourhood rich in social practices and relations.

26 Another performative social praxis is at work as well. [murmur] actively encourages people to take walking tours of the neighbourhoods and use cell phones to explore stories. Sawhney remarks, "we wanted [the project] to be engaging [. . .] to encourage people to get away from the [computer] screen and go physically experience these places" while listening to the stories (Alderman). In some cases, urbanites literally stumble into [murmur] during the course of their pedestrian activities, their curiosity piqued by the strange green signs with phone numbers on them (an experience described in the 25 September 2003 edition of Eye Weekly, above). The project’s emphasis on pedestrian culture (indeed Micallef now writes an urban culture column for Spacing magazine) situates it both within the practices of everyday life defined by de Certeau and in the radical gestures of Situationist psychogeography.

27 In de Certeau’s chapter on "Walking in the City" he speaks of how pedestrians read the city as a set of signs, but also, more importantly, write it as well. "The story begins on ground level, with footsteps," he writes (97). Further, he notes thatThe act of walking is to the urban system what the speech act is to language [. . .] uttered. [. . .] it is a process of appropriation of the topographical system on the part of the pedestrian (just as the speaker appropriates and takes on the language); it is a spatial acting-out of the place (just as the speech act is an acoustic acting-out of the language); and it implies relations among differentiated positions (97-98).Here, de Certeau echoes Saussure and Derrida in pointing out that a system of signs depends on their relational differences in order to be meaningful. Walking, then, as spatial production and as space of enunciation, is both a practice of everyday life and source of performative praxis; the speech act and the stroll are seen as similar expressive deployments of communicative action. How we walk, where we walk, what we do while walking become tactics that, over time, nudge the city into new iterative arrangements. (Critical Mass comes to mind as a similar analogue in terms of the communicative action of bicycling.) Simply put, our practiced proxemics affect the city over time. If pedestrians decide to walk on the grass or to make a community a no-go zone, over time this iteratively affects the composition of streets, cities. . . and even subjects.

28 As Steven Johnson writes in his book Emergence, "it is the sidewalk—the public space where interactions between neighbours are the most expressive and most frequent—that helps us [organize the composition of a neighbourhood]. In the popular democracy of neighbourhood formation, we vote with our feet" (91). In viewing neighbourhoods and cities as "patterns in time," Johnson stresses their emergent and self-organizing aspects (91, 104). He recognizes that such systems are complex iterative processes that result in a "materialization of effects" (in Butler’s memorable phrase). The neighbourhood that emerges over time is an effect of performative social actions and relations of subjects who "vote with their feet."

29 Pedestrians (re)write the city by walking. As a kind of story, a walk is a makeshift thing "composed with the world’s debris." It is composed of leftovers and the "fragments of scattered semantic places," including the heterogeneous details and excesses that supplement existing systems of organization. The walk exceeds the rationalized order of a city that is "punched and torn open by ellipses, drifts and leaks of meaning: it is a sieve order" (de Certeau 107). Part of what [murmur] attempts to do is produce this excess of meaning in the city, to replace the grid with the story, to ensure that "what the map cuts up, the story cuts across" (de Certeau 129). A reporter who stumbled across the [murmur] project by accident remarked that "after listening to a couple [of stories], we found ourselves wandering around the market with our phones searching for little green signs" ("Walk Softly"). The work therefore changes our relationship with the city, our appreciation for it, and changes "what a city is for": the city as interface, the city as play, the city as theatrum. The day we "searched for little green signs" becomes a walk and narrative in itself.

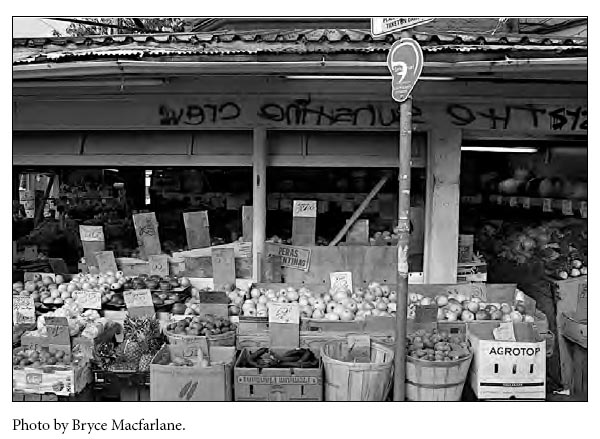

Display large image of Figure 3

30 As Micallef notes, "Discovering how the city changes as you stroll through it excites us [...], that by stepping outside of the daily routine—a psychogeographic derive—and approaching the city from a different perspective than the usual, [we believe] a richer perspective can be achieved. [. . .] Hearing these stories," he continues, "like a psychogeographic walk through a city, can give one a new appreciation of places that may have seemed nondescript or banal" (qtd. in O’Donovan). Psychogeography was defined by Guy Debord and the Situationists as "the study of [. . .] specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals" (Debord, "Introduction"). The Situationists, active in Europe in the 1960s, sought to reconcile Surrealism and Marxism though the integration of art with everyday life. Their critiques of capitalism, urbanism, and the spectacle of consumer culture have been highly influential on discourses of urbanism and anarchism, while many of their critical practices have been adopted by modern-day activists, performers, and psychogeographers.

31 Central to much of Situationist thought is the notion of the "spectacle" as laid out in Debord’s 1967 polemic The Society of the Spectacle: "In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation." Building on Marx’s notion of capitalist alienation, he remarks that "[t]he spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images" (Society). It is a result of the current mode of production, which prioritizes images and consumption over a directly experienced reality. Situationist tactics are designed as a means of re-experiencing the world from a new perspective, as a work of art, rather than repeating the same patterns of an inauthentic existence with the spectacle.

32 The Situationist practice of the dérive (or drifting) is a walking practice inherited from Dada and Surrealism, and this concept was a major influence on the construction of [murmur]. Tactically, the dérive of psychogeography involved "locomotion without a goal," in which "one or more persons during a certain period, drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there" (Debord"Theory"). It is, to use Deleuze’s term, an act of deterritorialization, whereby the normal connections and relations that constitute a given space are interrupted and suspended. The reterritorialization of space occurs in the construction of new meanings, making new connections and new discoveries by going to places not predetermined by our habits, obligations, schedules or needs. This reterritorialization is also effected through the making of new cognitive maps drawn from subjective experience. These new maps, centered around the subject—like de Certeau’s stories—cut across, exceed, and even replace the rationalized grid of urban planning. The dérive functions through trajectories of desire, curiosity, and chance more than anything else, in order that we might reconceptualize the city.

33 The new conceptual map of the city produced by this process is a heterogeneous assemblage of experiences and desires, more hypertext narrative than cartographic representation. Describing the importance of the psychogeographical dérive, Micallef says that "[p]eople get locked into their daily path and they tend not to veer off that path. They go from pocket to pocket and just experience the stuff that they know" (Underwood). In short, our everyday experience of the city corresponds to a linear text, "locked into" certain paths and static narrative trajectories. Psychogeography, on the other hand (and particularly the dérive), works to break up linear pedestrian activities so that they resemble something much more like an itinerant hypertext laid out atop the city. Each node has multiple points of entry and exit, and the order in which we explore them affects the overall meaning that we accord the experience.

34 For example, the [murmur] sign posted at Bloor and Lippincott (Annex #276663: Jaclyn) allows the listener to access stories about a father’s spontaneous visit to see his daughter, or a woman who loses her roommate’s cat while house-sitting. From here one has a choice of four adjacent nodes: northeast to Seaton Walk Park, east to 535 Bloor, southwest to 581 Markham or northwest to 506 Bloor (see [murmur]/Annex). At Seaton Walk Park, the spectator can hear about the attempt to establish a park with indigenous plants, or the story of watching the police attempt to arrest an urban nudist over lunchtime (#278663: Geoff and Molly). Wandering east to 535 Bloor results in a story about seeing a man intently reading Hypnosis for Beginners (#275661: Roberto). If you travel southwest, you can hear stories about the ghost of the Victory Café and how Patrick almost burnt the bar down, as well as childhood anecdotes about going to a father’s hidden art studio (#267671: Patrick and Perry). Choosing to go northwest to 506 Bloor would reveal stories centered around the Bloor Cinema: about a secret admirer of the boy who changed the marquee signs and the family who ran the cinema for years (#275664: Jaclyn). As one can see from this short list of selections, the possible narrative trajectories are varied and extensive, allowing each pedestrian audience member to choose his or her own fairly unique path through these stories. The street-level experience of [murmur] illustrates the actual strength of the dérive: creating non-linear, combinatory storylines. The psychogeographical techniques of the Situationists (and the stories unearthed by them) can be seen in this way to create a kind of spatial hypertext of the city avant la lettre.

35 The appeal of the dérive both as a way of walking and of seeing, writes Guy Debord, is not an appreciation of "plastic beauty—the new beauty can only be beauty of situation—but simply the particularly moving presentation, [. . .] of a sum of possibilities" ("Introduction"). Much in the same way that McLuhan sees the built environment as a series of "programmed happening[s]" (113), the dérive emphasizes "the beauty of the situation," of the context and one’s relationship with it, as the most important element. [murmur]’s roots in psychogeography can be seen in this way—as the construction of a situation whereby the audience member must reconcile real and imaginary elements of a site and choose a non-linear, hypertextual path in order to multiply narrative possibilities.

36 The element of the walk, the discovery of reified places transformed into lived spaces, alters the perspective of the user along the way. They may ask, "What about all these other buildings that don’t have signs? What are their stories? What stories do I have? What other stories are possible?" The absence of signs comes to take on an increased presence in the mind of the user, forcing him/her to reconceptualize or speculate what living in a city of signs—literal, annotative or semiotic—really means. This perceptual shift of "seeing the city otherwise"—of seeing it being historical, contingent, social, and above all discursive—is what the enterprise of psychogeography is all about.

37 The experience of the [murmur] project, as a site-specific art work that forces us to reconcile real and imaginary space, as an auditory mise en scène that interpellates its listener into the mimetic frame, as a psychogeographic dérive designed to make us "see the city otherwise" and as a cybercartographic map that emphasizes situated knowledges, is itself multiple. However, the underlying theme of these experiences is their ability to help us understand that historical, contextual, and subjective information is latent in materiality and, similarly, it allows us to see that a city results from the performative processes of spatial production. In short, it forces us to change what we mean when we ask the question, "Where are you right now?"

Works Cited

Alderman, Nathan. "Using Cell Phones as Neighborhood Tour Guides." New Voices: Citizens Media Spotlights. 27 December 2004. 2 September 2007 http://www.j-newvoices.org/index.php/site/story_spotlight/using_cell_phones_as_neighborhood_tour_guides/.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Revised ed. London: Verso, 1991.

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1996.

Barthes, R. "Semiology and the Urban." The City and the Sign: An Introduction to Urban Semiotics. Ed. M. Gottdiener and A. Ph. Lagopoulos. New York: Columbia UP, 1986. 87-98.

Beck, Alan. "Cognitive Mapping and Radio Drama." Consciousness, Literature and the Arts 1.2 (July 2000). 2 September 2007 http://www.aber.ac.uk/tfts/journal/archive/cog.html.

Bowness, Anna. "Tales of Toronto." Utne Reader – Online. Adapted from Broken Pencil Nov/Dec 2004. 2 September 2007 http://www.utne.com/2004-11-01/TalesofToronto.aspx.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Debord, Guy-Ernest. "Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography." Les Lèvres Nues 6 (1955). 2 September 2007 http://library.nothingness.org/articles/all/all/display/2.

— . "Theory of the Dérive." Situationist International Online. Trans. Ken Knabb. Les Lèvres Nues 9 (November 1956). Reprinted in Internationale Situationniste 2 (December 1958) 2 September 2007 http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/theory.html.

— . The Society of the Spectacle. Trans. Black and Red. Paris: Black and Red. 1967. 2 September 2007 http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/display/16.

de Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Steven Rendall. Berkeley, CA: U of California P, 1984.

Derrida, Jacques. Limited Inc. Evanston, IL: Northwestern UP, 1988.

— . "Signature Event Context (1972)." Margins of Philosophy. Trans. Alan Bass. Chicago: Chicago UP, 1982. 307-30.

Haraway, Donna J. "Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective." Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: the Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991. 183-201.

Hemment, Drew. "Locative Arts." August 2004. 2 September 2007 http://www.drewhemment.com/2004/locative_arts.html.

Herhold, Scott. "ZeroOne has code to folksy spirit of city." Mercury News 10 August 2006. 2 September 2007 http://www.mercurynews.com/mld/mercurynews/news/columnists/scott_ herhold/15240727.htm?template=contentModules/printstory.jsp.

Hunter, Mike. "McLuhan’s Pendulum: Reading Dialectics of Technological Distance." The Sarai Reader 03: Shaping Technologies. Ed. Jeebesh Bagchi et al. Faridabad, India: Thomson, 2003. 144-56.

Johnson, Steven. Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software. New York: Penguin, 2001.

Kaye, Nick. Site-Specific Art: Performance, Place and Documentation. London: Routledge, 2000.

Lapsley, Robert, and Michael Westlake. Film Theory: An Introduction. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1988.

Laurel, Brenda. Computers As Theatre. New York: Addison-Wesley, 1993.

Loureno, Jos. "The Word on the Street is Murmur." The Toronto Star 20 September 2003: J07.

McLuhan, Marshall. "Environment as Programmed Happening." Knowledge and the Future of Man: An International Symposium. Ed. Walter Ong. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968.

Micallef, Shawn, Gabe Sawhney and James Roussel. "[murmur] Toronto." August 2003. 2 September 2007 http://murmurtoronto.ca.

[murmur]. Company homepage. 2 September 2007 http://murmurtoronto.ca/.

O’Donovan, Caitlin. "Murmurings: An Interview with Members of the [murmur] Collective." Year Zero One Forum 12 (Summer 2003). 2 September 2007 http://www.year01.com/forum/issue12/caitlin.html.

Pearson, M., and Michael Shanks. Theatre/Archaeology. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Perlman, Stacey M. "The Art of Mobile Technology." The Boston Globe – Online 18 April 2005. 2 September 2007 http://www.boston.com/business/technology/articles/2005/04/18/the_art _of_mobile_technology/.

Plant, Sadie. On the Mobile: The Effects of Mobile Telephones on Social and Individual Life. Schaumburg, IL: The Motorola Media Center, 2001. 2 September 2007 http://www.motorola.com/mot/doc/0/234_MotDoc.pdf.

— . The Most Radical Gesture: The Situationist International in a Postmodern Age. London: Routledge, 1992.

Pugh, Abigail. "Flâneur by phone." Eye Weekly 19 August 2004, City Section. 2 September 2007 http://www.eye.net/eye/issue/issue_08.19.04/city/murmur.html.

Rossi, Cheryl. "Green ears reveal Chinatown’s secrets." The Vancouver Courier – Online 10 August 2005, News Section. 2 September 2007 http://www.vancourier.com/issues05/ 082105/news/082105nn6.html.

Rushkoff, Douglas. "Honey, I Geotagged the Kids." The Feature 23 March 2005. 2 September 2007 http://www.thefeaturearchives.com/101490.html.

Ryan, Carol-Ann. "Listen to the [murmur]." Surface & Symbol 18.5 (June 2006). 2 September 2007 http://www.scarborougharts.com/sac/surface_symbol/july06/july06_murmur.htm.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. "Cyberspace, Cybertexts, Cybermaps." Dichtung-Digital/Contributions on Digital Aesthetics (2004): 1. 2 September 2007 http://www.dichtung-digital.org/2004/1-Ryan.htm.

Soja, Edward W. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. London: Blackwell, 1996.

Toman, Sam. "[murmur] Whispers Sweet Something In Your Ear." Sceneandheard.ca 5.6 (30 September 2003). 2 September 2007 http://www.sceneandheard.ca/article.php?id=260.

Underwood, Nora. "Go to Kensington, call a friend." Globe and Mail 20 December 2003: M7.

Urry, John. The Tourist Gaze. 2nd ed. London: Sage, 2002.

"Walk Softly, Carry a Tiny Phone." Eye Weekly (uncredited) 25 September 2003, Wandering Eye Section. 2 September 2007 http://www.eye.net/eye/issue/issue_09.25.03/city/wandering.html.

Whyte, Murray. "Telling signs of our heritage." The Toronto Star 29 August 2004: B06.

Yates, Frances. The Art of Memory. London: Plimco, 1996.