Articles

On Being or Becoming a Secondary School Drama/theatre Teacher in a Linguistic Minority Context

Mariette ThébergeUniversity of Ottawa

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to reflect upon what it means to be or to become a secondary school drama/theatre teacher in a linguistic minority context such as the one in francophone Ontario. The conceptual framework is inspired by Mucchielli’s concept of identity (14) and Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory (9-22, preface) and is based on the conception of the teacher as conveyor of culture (Zakhartchouk 19-20, ch. 1; Gohier 233). Acknowledging the gap that may exist between the passion for theatre and the reality of the classroom, this study allows us to question the motivation that underlies the choice of this profession. The analysis of results emphasizes the extent to which the support of the school and school board administration is a determining factor in the decision to pursue a career in this profession and in this artistic discipline.Résumé

Cette recherche a comme objectif de réfléchir à ce que signifie être et devenir enseignant au secondaire en art dramatique/théâtre dans un contexte linguistique minoritaire comme celui de l’Ontario français. Le cadre théorique s’inspire de la définition du concept d’identité de Mucchielli (14) et de la théorie de l’autodétermination de Deci et Ryan (9-22; preface) et s’appuie sur la conception de l’enseignant en tant que passeur culturel (Zakhartchouk 19-20; ch. 1; Gohier 233). Concevant l’écart qu’il peut y avoir entre la passion de faire du théâtre et la réalité de la salle de classe, cette recherche permet d’interroger la motivation qui sous-tend ce choix de profession. L’analyse des résultats souligne à quel point le soutien de la direction d’école et celui du conseil scolaire sont un facteur déterminant dans le choix de poursuivre une carrière dans cette profession et dans cette discipline artistique.Introduction

1 The purpose of this study is to reflect upon what it means to be or to become a secondary school drama/theatre teacher in a linguistic minority context such as the one in francophone Ontario. Ontario is Canada’s most populous province, with a population of 12.5 million in an area covering 1,076,395 square kilometres (almost twice that of France). Its 550,000 francophone inhabitants represent the country’s largest linguistic minority. This minority francophone context is of particular interest for studies of motivation in the teaching of drama/theatre. Firstly, theatre gives voice to the cultural expression of the francophone community. Secondly, even if the Canadian constitution recognizes French and English as official languages, there is no guarantee of francophone cultural vitality in each province, due to the predominance of Anglophones in North America and the widely dispersed Francophone population. In a minority context, Francophones want to feel at home by expressing their culture. The political debate with respect to the cultural differences of these two linguistic groups is far from over. A related issue is the effect of globalization on linguistic practices and the eventual disappearance of certain languages, such as French, in the twenty-first century (Calvet 77).

2 In order to fully understand the Franco-Ontarian context, one must remember that the school environment has always been the core element in the existence and survival of the French-speaking population of Ontario. As indicated by Cazabon (55) and Bernard (520-22), schools represent the very foundation of French culture in the community, allowing an increased cultural awareness among youth and the development of a sense of cultural belonging (Théberge, Construction 8). In the absence of this strong attachment, the identity of an individual can be unclear (Mucchielli 62). The school environment, therefore, has an essential socio-cultural role among the minority francophone population in Canada, not only in terms of the quality education it offers, but also as an institutional authority that encourages linguistic recognition and prestige (Association 28; Ministère 6; Théâtre Action 13-19).

3 As French-language schools were only allowed in Ontario starting in 1969, the issue of examining what motivates or does not motivate people to be or to become teachers of drama/theatre in a French minority context is essential. Those who were part of the initial artistic expansion in the Franco-Ontarian community are rapidly approaching retirement age. Failure to document how these teachers live their role in a minority context can signify the loss of an entire knowledge base of experience that might be beneficial to generations of new teachers arriving on the scene. Furthermore, many young Canadians between fourteen and seventeen years of age find it more "cool" to be anglophone than francophone. The attraction of the country’s majority culture is undeniable (Haentjens and Chagnon-Lampron 6-7; Théâtre Action 23).

4 Based on my experience of more than thirty years in this community, first as an artist and then as professor in a teacher education program, I will address the issue of motivation to be or to become a secondary school drama/theatre teacher. I will first specify the conceptual framework on which the research is based. Then I will present and discuss the results obtained during the data collection.

Conceptual Framework

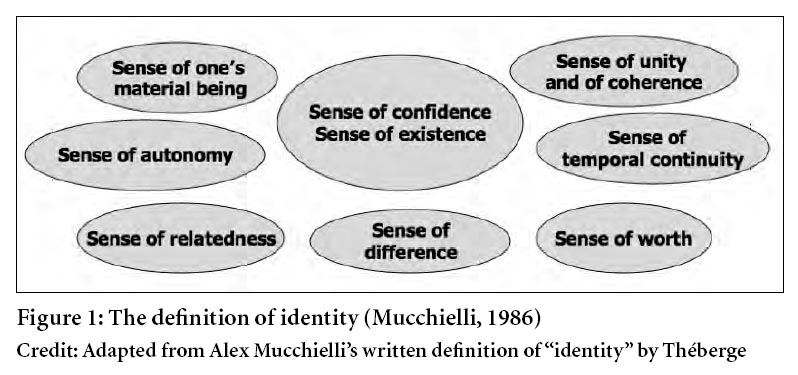

5 This study is inspired by Mucchielli’s concept of identity, which he suggests is based on a sense of one’s material being, of unity, and of coherence; a sense of temporal continuity, of relatedness, of difference; a sense of worth, of autonomy, of confidence; and a sense of existence (14).The senses of confidence and existence represent the core of the entire group.

Figure 1: The definition of identity (Mucchielli, 1986)

Display large image of Figure 1

6 Within this conception of identity, the sense of confidence constitutes the essential foundation on which is based "the central effort of the sense of existence" that allows a person to give meaning to his actions. The sense of relatedness results from a process of integrating social values. The sense of difference is linked to the sense of relatedness and contributes to the awareness of self in relation to others. For example, a person immersed in a totally unfamiliar environment and confronted with things that are foreign learns to recognize identity referents. This also provides an opportunity to develop a sense of worth, which underlies the ability to adopt different points of view. As for the sense of autonomy, it corresponds to the need among humans to assert their identity in relation to the group of which they are a part.

7 This study is also inspired by the self-determination theory that qualifies motivation on a continuum by considering the elements of amotivation, extrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation in a person (Deci and Ryan 9-22). According to this theory, amotivation is the pole that represents a lack of motivation. Extrinsic motivation is situated between amotivation and intrinsic motivation. It is rooted in an instrumental worth, or external reason, and shifts from reward, or external regulation, to introjection, then to identification and integration (Laguardia and Ryan 290-93). Introjection reflects the beginning of an interiorization of worth, without presupposing a personalized control. Identification and integration represent, for their part, an internal control that is more and more pronounced, a greater congruence of values and needs. Intrinsic motivation is the pole opposite to amotivation. It reflects behaviour that originates from satisfaction and interest.

8 This study is also based on the conception of the teacher as conveyor of culture (passeur culturel) (Zakhartchouk 19-20). As Gohier states, the teacher among his students acts not only in the sense of transmitting knowledge drawn from their own culture and other cultures, but also as a person who creates links:Conveyor of culture, building bridges between different cultural registers, but also linking the sensible and the sensed through the cultural object that becomes a linker, serving as an interface between people. Establishing links, a difficult yet essential finality of teaching that can only be achieved through education that aims to unite the person within his own self, in all his various dimensions, as well as to the other. Such is the ultimate aim of education to the understanding and to the relation. (Gohier 233, trans. by Théberge)According to this conception, the teacher is a cultural model who is likely to help understand the present and past complexity of events occurring in the immediate community and in society.

Methodology

9 In order to better understand what motivates or does not motivate a person to be or to become a drama/theatre teacher in the context of Ontario’s French-language secondary schools, this study favours an approach that is qualitative/interpretive in nature. This approach recognizes the importance of the meanings that people give to the phenomena under study. As Savoie-Zajc states, "research on the interpretive trend is thus driven by the desire to better understand the meaning that a person gives to his experience" (172, trans. by Théberge). Such research can also allow "the study of affectivity, of commitment, of identity investment" as well as "their relations with the shapes, the logic and the functions of social thought" (Anadón and Gohier 30). As for the teaching of drama/theatre in a linguistic minority context, this approach proves to be all the more appropriate, since it is indispensable to consider the portion of affectivity, commitment, and investment that the exercise of the teaching profession requires, especially in the discipline of drama/theatre (Théberge, « Le rôle » 111-14).

10 This study also favours a triangulation strategy, drawing on a tripartite conceptual framework, i.e. Mucchielli’s definition of identity, Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory, and the conception of the teacher as a conveyor of culture. Savoie-Zajc explains it in this manner: "We now define triangulation as a research strategy during which the researcher superimposes and combines several perspectives, be they theoretical in nature or based on methods and people" (194, trans. by Théberge). This strategy brings out various complementary perspectives during the course of data analysis.

11 For the purposes of the present study, I invited approximately thirty drama/theatre teachers from French language secondary schools in Ontario to participate. Eight of these teachers accepted the invitation. Two of the participants were at the beginning of their career, having less than five years teaching experience. Three others had between five and fifteen years experience and the remaining three had been teaching for over fifteen years. Three of the participants had a priori considered teaching drama/theatre in secondary schools and chose this artistic discipline when they enrolled in the teacher training program. As for the other five, they were attracted to drama/theatre after having completed their teacher education. A limitation of this research is the fact that those willing to participate are likely teachers who enjoy their jobs.

12 Two of the schools included in the study are located in large cities, with a population greater than 500,000. Five schools serve a rural population, despite being located in cities with a population of approximately 50,000, and the remaining school is located in a small town with a population of less than 5,000.

13 The data collection was done through semi-structured interviews, lasting between thirty and ninety minutes. I was able to gather a collection of statements that led to a point of data saturation. The questions addressed the history of each participant’s teaching career, as well as the motivational elements to be or to become a secondary school drama/theatre teacher. To start, I identified motivational elements expressed in the statements of each participant. I then analyzed interview content for elements of identity definitions and conceptions of the teacher as conveyor of culture. Lastly, I established a link between identified motivational elements, identity definitions, and conceptions of the teacher as conveyor of culture. In so doing, I took into account each of the three theoretical perspectives during the data analysis.

Presentation and Discussion of the Results

14 The results suggest that there is a gap between the passion for performing theatre and the reality of the classroom. The results also highlight underlying links within the participants’ conceptions of identity and within their vision of themselves as conveyors of culture. In this section, I will present and discuss these results. To begin, I will present the participants’ motives for amotivation in relation to the reality of the classroom. I will then examine those of extrinsic motivation in relation to the teaching profession and, lastly, those of intrinsic motivation in relation to the satisfaction of performing theatre with young people.

Motives for Amotivation

15 It may seem odd to speak of motives for amotivation or motives for the absence of motivation. However, the principal motive for amotivation is the clash with the school culture that each participant faced in the course of his or her career. Whether novice or experienced, a drama/theatre teacher arriving at a school, with or without teaching experience, can feel completely at a loss. This leads to a fundamental questioning of one’s very ability to teach and of one’s sense of confidence. The following remark shows how a teacher with over twenty years experience overcame this situation:I have lived through several beginnings of careers. When I came to this school, the first month was sheer hell. So much so, that I even cried once. I said to myself: ‘I’ve lost it… nothing works anymore.’ Funny. In the evening, I spoke to my wife—who has thirty years’ experience—she said to me: ‘Don’t you realize that you are new?’ The students tested me. It was ridiculous. They would shout. I had never seen anything like it. The teacher they had before was burned out. The students had always done whatever they wanted, running everywhere, hiding behind the curtains, curtains swinging back and forth, it was a real zoo. Day after day after day. At the time, I had twenty years experience. During the first semester, I thought I was going to be worn out. It was like starting all over… Finally, in the second year, I loved it." (Confidential Subject 8, pp. 8-9, trans. by Théberge)

16 The content of the interview shows that even if someone is motivated to teach drama/theatre, the clash with the reality of the classroom has significant repercussions on the decision to pursue or not to pursue a career 1) in teaching and 2) in the field of drama/theatre.The artistic ideal that cannot be transmitted and the difficulties in communication with adolescents wear down the willingness and quickly become motives for amotivation.

17 These motives are particularly present in the linguistic minority context of Ontario, especially since the abolition of grade thirteen. This abolition in secondary schools has repercussions on the number of registrations in elective courses such as drama/theatre (Théâtre Action 17). Considering the low density of francophone population in certain regions of Ontario, a number of secondary schools offer the compulsory arts course either in grade nine or in grade ten. In grade ten, the groups are made up of students who have already taken the compulsory drama/theatre course the preceding year and students who have not yet done so. It follows therefore that some of the students have already received an initial level of training in the artistic discipline and choose to continue in grade ten out of interest, while others have not received the initial training and only register in the course to meet the requirements of the Ministry. The situation is well described by the following teacher’s comment.Last year in grade ten, ten of my strongest students in theatre found themselves grouped with twenty beginners. It is a good thing that I had some experience, for the ten students quickly understood the situation and were quickly fed up. (Confidential Subject 8, p. 4, trans. by Théberge)In such situations, which are frequent, it is very difficult to encourage a sense of relatedness and to promote coherence and unity in the group—normally, the opposite occurs. In a majority context, such situations are infrequent because the base population is large enough to allow the creation of distinct classes based on the level of training already received.

Motives for Extrinsic Motivation

18 The teaching profession offers certain advantages to those having the status of artist. The motive of external regulation that seems most evident in the interviews is the financial stability that a regular teaching position provides. Among the external motives that favour the interiorization of social values underlying the profession, there is the approval of the career choice from the immediate family, as well as the recognition from the community during theatre productions.

19 Furthermore, the analysis of the interviews highlights the extent to which the support of the administrative staff in schools and school boards given to drama/theatre teachers is important. Indeed, this support is essential in the attribution of courses, during the organization of shows, and when problematic situations arise that are linked to students’ behaviour. This last motive is mentioned in the teachers’ comments as a decisive factor in the choice they make not only to continue teaching in this artistic discipline, but also to perceive themselves as conveyors of culture in their context. A lack of strong support for drama/theatre as an essential component of students’ education on the part of the school and the school board becomes a motive for amotivation to be or to become a secondary school drama/theatre teacher in the short- and long-term. Such situations can also apply to elementary school drama teachers (Anderson 12).

20 In Ontario’s francophone minority context, the financial motive of external regulation for teachers—the high salary—does not last long. In other words, participants mention this motive, yet make it clear that survival would not be possible without the strong interest and support of parents, of the community, and especially of the administrative staff of schools and school boards. The participants themselves explain that there is a constant need to assert their difference. This difference stems first from the types of activities that they propose (Théberge, « Construction » 139-40). Secondly, being francophone in a majority anglophone context often requires an emphasis on content that is unfamiliar and inaccessible to students.

21 For example, it is practically impossible for certain students to see French theatre in their community. The difficult access to French bookstores that would facilitate the selection of French plays, the attraction generated by the English-language media among adolescents, and even the difficulty students have to improvise in French constitute tangible barriers to the practice of the profession. Furthermore, as conveyors of culture, teachers of drama/theatre also ask their adolescent students to assert their difference.There is a need for increased consciousness among youth. It is necessary to heighten their awareness of the importance of the French language. Motivating youth in a minority context to speak French is very difficult. Everything around them happens in English and some find it difficult to express themselves freely and spontaneously in French. And yet, it is their culture… a part of their culture… (Confidential Subject 5, p. 4, trans. by Théberge)For these students however, being francophone and identifying oneself as such is not easy. In a person’s conception of identity, there are strong ties between the sense of relatedness, of difference, and of worth.In the city where I live, a big anglophone environment, we sometimes feel quite alone as francophones. It is therefore comforting to experience emotions together, to take part in a common project, and to devote ourselves entirely to it. To live one’s culture and to give it life—that is why I am here. (Confidential Subject 2, p. 6, trans. by Théberge)The work of drama/theatre teachers thus becomes all the more important, as the social context in which they practice their profession is in the minority and young people do not necessarily identify themselves at the outset with the francophone culture.

Motives for Intrinsic Motivation

22 In describing their teaching career path, participants also highlight motives for intrinsic motivation, including the satisfaction of performing theatre with youth. This motive appears in participants’ remarks once they have gone beyond the expectations of external motives. Participants realize that teaching allows them to pursue their interest in theatre. They recognize their important contribution to the students, get a lot of satisfaction out of their work, and are proud to contribute to the blossoming of youth. The schools and school boards even promote the quality of their work:It is wonderful to see the way they work and to realize the extent of their potential. (Confidential Subject 1, p. 4, trans. by Théberge)The young people are proud of what they are doing. In the end, they see everything fall into place, and are thankful for all the hours spent with the troupe. There is a sense of what I call well-being in performing theatre, devoting oneself entirely to a project. For many of them, it is one of the first times they live such an experience in French; a project in a group, that is not only fun, but in French. (Confidential Subject 2, p. 3, trans. by Théberge)This satisfaction gives the teachers enough energy for the various projects required in the practice of the profession (Csikszentmihalyi 195). Defining themselves as cultural models and resource persons who are essential to the artistic vitality of the environment, the teachers are vivid examples of conveyors of culture without whom Franco-Ontarian culture would not evolve. As such, in relation to a linguistic majority context, the participants who display intrinsic motivation distinguish themselves by the devotion and courage that is required to assert tirelessly throughout a lifetime a difference that removes nothing from the person’s sense of worth, but that can be difficult to deal with, given the fatigue that it can generate.

Conclusion

23 In this article, I address the issue of what motivates or does not motivate a person to be or to become a secondary school drama/theatre teacher in a linguistic minority context. While the participants reflect upon their cultural identity and their loneliness as francophones in this context, the clash with the culture of the community and the school constitutes the principal motives for amotivation. Furthermore, even if the financial stability offered by a regular teaching position can be a motive of external regulation, the support of the administrative staff of the school and school board remains influential in the decision to pursue a career in this field. As for the satisfaction of performing theatre with young people, this intrinsic motivation enhances the teachers’ pride and encourages them to pursue a long-term teaching career. It is, however, still necessary to continue documenting the day-to-day practice of this profession in subsequent research, in order to understand the implications for both education and theatre.

Works Cited

Association canadienne d’éducation de langue française. Cadre d’orientation en construction identitaire. Québec: Association canadienne d’éducation de langue française, 2006. 7 avril 2007 www.acelf.ca/c/fichiers/Cadreorientationconstructionidentitaire.pdf.

Anadón, Marta, and Christiane Gohier. « La pensée sociale et le sujet: une réconciliation méthodologique ». Les représentations sociales. Des méthodes de recherche aux problèmes de société. Ed. Monique Lebrun. Montréal: Logiques, 2001. 19-41.

Anderson, Michael. "The Professional Journey of Two Primary Drama Educators." NJ: The Journal of Drama Australia 27.1 (2003): 5-14.

Bernard, Roger. « Les contradictions fondamentales de l’école minoritaire ». Revue des sciences de l’éducation 23.3 (1997): 509-26.

Calvet, Louis-Jean. Le marché aux langues: Les effets linguistiques de la mondialisation. Paris: Plon, 2002.

Cazabon, Benoît. « De la mission culturelle de l’école et de la pédagogie du français langue maternelle ». Canadian Ethnic Studies / Études ethniques au Canada 25.2 (1993): 52-64.

Confidential Subject 1. Personal Interview. 23 April 2004.

Confidential Subject 2. Personal Interview. 23 April 2004.

Confidential Subject 5. Personal Interview. 23 April 2004.

Confidential Subject 8. Personal Interviw. 25 February 2005.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly et al. Talented Teenagers: The Roots of Success and Failure. New York: Cambridge UP, 2001.

Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. Handbook of Self-Determination Research. Rochester: U of Rochester P, 2002.

Gohier, Christiane. « La polyphonie des registres culturels, une question de rapports à la culture. L’enseignant comme passeur, médiateur, lieur ». Revue des sciences de l’éducation 28.1 (2002): 215-36.

Haentjens, Marc, and Geneviève Chagnon-Lampron. Recherche-action sur le lien langue-culture-éducation en milieu minoritaire francophone. Ottawa: Fédération culturelle canadienne française, 2004.

Laguardia, Jennifer G., and Richard. M. Ryan. « Buts personnels, besoins psychologiques fondamentaux et bien-être: théorie de l’autodétermination et applications ». Revue québécoise de psychologie 21.2 (2000): 281-304.

Ministère de l’Éducation et de la Formation de l’Ontario. Politique d’aménagement linguistique de l’Ontario pour l’éducation en langue française. Toronto: Imprimeur de la Reine pour l’Ontario, 2004.

Mucchielli, Alex. L’identité. Collection Que sais-je? Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1986.

Savoie-Zajc, Lorraine. « La recherche qualitative / interprétative en éducation ». Introduction à la recherche en éducation. Ed. Thierry. Karsenti and Lorraine Savoie-Zajc. Sherbrooke: Éditions du CRP, 2000. 171-98.

Théâtre Action. « Étude de l’impact socio-économique et culturel de l’activité théâtrale en Ontario français ». La force du theatre. [Secteur scolaire.] Ottawa: Théâtre Action, 2003.

Théberge, Mariette. Construction identitaire et éducation artistique dans un contexte canadien francophone minoritaire. Lisbonne: UNESCO, 2006. 5 avril 2007 http://portal.unesco.org/culture/admin/file_download.php.

— . « Construction identitaire et éducation théâtrale dans un contexte rural franco-ontarien ». Revue Éducation et francophonie. 34.1 (2006): 133-47. 12 avril 2007 http://www.acelf.ca/c/revue/index.php.

— . « Le rôle de responsables de troupes dans des productions théâtrales au secondaire ». The Universal Mosaic of Drama/Theatre: The IDEA 2004 Dialogues. Ed. Laura A. McCammon and Debra McLauchlan. City East, Australia: IDEA Publications, 2006. 109-17.

Zakhartchouk, Jean-Michel. L’enseignant, un passeur culturel. Paris: ESF, 1999.