Articles

Set Design as Cosmic Metaphor:

Religious Seeing and Theatre Space

Tanit MendesRyerson University

Janet Tulloch

University of Ottawa

Abstract

Gary Taylor, a noted Shakespearean scholar, defines "theological architecture" as theatre space that is built with a religious hierarchical understanding. This paper considers the use of theological architecture to define the physical space of gods and humans in Michael Levine’s set designs for the Canadian Opera Company’s Die Walküre and Siegfried on Toronto’s Hummingbird stage. In particular this paper examines Levine’s use of theatrical space to create both vertical and horizontal cosmologies, the former embedded within the western stage itself and the latter embedded within the Norse religion that informs the Ring Cycle. The effect produces an alternating form of perception for the audience-viewers, the first psychological and the second a form of viewing known as"religious seeing."Résumé

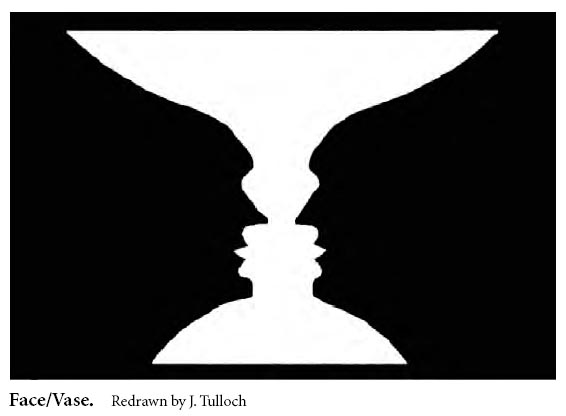

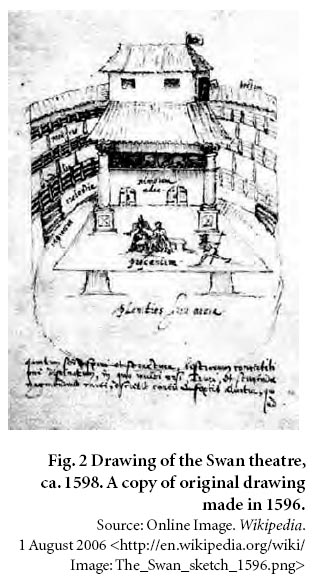

Le spécialiste de Shakespeare, Gary Taylor, définit « l’architecture théologique » comme étant la construction d’un espace dramatique fondée sur une hiérarchie à caractère religieux. Cet article examine les décors mis au point par Michael Levine pour les opéras Die Walkürie et Siegfried du Canadian Opera Company au Hummingbird de Toronto afin de voir comment l’architecture théologique est utilisée pour définir l’espace physique des dieux et des êtres humains. En particulier, cet article examine comment Michael Levine utilise l’espace dramatique pour créer des cosmologies verticales et horizontales; les premières sont empruntées au théâtre occidental alors que les secondes relèvent de la religion nordique qui a influencé les décors du « Ring Cycle. » Cela produit deux formes de perceptions alternantes chez les spectateurs; la première étant psychologique et la deuxième composant une forme d’observation connue sous le nom de « perception religieuse. »1 Despite director Francois Girard’s declaration that "In Siegfried, we’ve set the piece in the mind of [the character of] Siegfried and […] we went for a sort of psychic explosion,or implosion if you prefer" (qtd. in Vanstone, "Girard" 42), this article advances the position that Michael Levine’s innovative set designs for the Canadian Opera Company’s (COC) recent productions of Die Walküre (2004) and Siegfried (2005) can also be read as what Gary Taylor, a noted Shakespearean scholar, in Reinventing Shakespeare, calls"theological architecture"(15), theatre space that is built with a religious hierarchical understanding. As such, set design signifies the spatial location of gods, humans, and mythological creatures through the strategic use of perspective, lighting, symbolic colour, and form.While acknowledging the stage design’s successful transmission of the director’s intent, this paper suggests that through the use of theological architecture, the definition of space on stage in these operas can be read equally as divinely ordered (i.e.,cosmological) or as interior psychological space. The perception of theatrical space as cosmological belongs to a form of viewing known as "religious seeing"as described by S.Brent Plate,a scholar of religion and the visual arts at Texas Christian University.This type of perception is produced by the interaction between visual culture1 (which includes but is not limited to art, artefacts, and architecture) and certain types of spiritual viewing practices such as vision quests, meditation, and prayer that use material objects or settings (e.g., icons, thangkas, meditation gardens, sacred groves), as part of their practice.2 Plate describes "religious seeing" as a form of perception that is produced between the interaction of visual culture and religious practice. Typically, according to Plate, this activity"is situated within an environment conducive to belief, devotion, and transformation" (11). David Morgan, a theorist of religious visual culture, understands seeing as an active behaviour made up of a variety of visual practices that "rel[y] on an apparatus of assumptions and inclinations, habits and routines, historical associations and cultural practices" (Sacred Gaze 3). Morgan prefers the expression sacred gaze as it "designates the particular configuration of ideas, attitudes, and customs that informs a religious act of seeing as it occurs within a given cultural and historical setting" (3). "A gaze," according to Morgan, who postulates numerous yet related genres of the act, "is a practice,something that people do,conscious or not, and a way of seeing that viewers share" (Sacred Gaze 5). In our article we understand the theatre as an environment with the potential for viewer transformation, a place in which a number of species of the gaze are operative and triggered by "historical associations and cultural practices," whether audience members are conscious of such practices or not.While Girard explains the visual definition of theatrical space in Siegfried as interior psychological space (i.e., inside the head of the main character) (qtd. in Everett-Green, "Journey"; Everett-Green,"Fascinating"), this paper argues that Die Walküre and Siegfried provide spectators with a richer viewing experience when the dramatic action is read as occurring within the cosmos of ancient Norse religion and/or inside the head of the main character. Just as the well known face/vase optical illusion suggests that the same visual information equally presents two different perceptions to the eye, we suggest that the theatrical space and set designs of Michael Levine in these productions offer a similar bi-ocular experience of seeing (one psychological and one religious) for the operas’ viewing audience.

Face/Vase.

Display large image of Figure 1

2 To support this argument two main types of evidence are presented: scenographic and historical. Before discussing the scenographic evidence, we will show that there is strong historical evidence (including artistic and archaeological) for interpreting the theatrical space of these productions as cosmological. This evidence includes key ideas and images from the history of the western theatre, artefacts from ancient Norse religion, and selected documents discussing the relationship between art and religion written by Richard Wagner himself.Wagner’s own theoretical writings on the relationship between religion and art are particularly relevant to our discussion because he believed art, especially music, captured the true spirit of religion (particularly his own idiosyncratic view of Christianity) when institutionalized Christianity could no longer produce spiritual succour due to its insistence on the literal beliefs of its dogmas (Religion and Art, part I 213-24). Secondly, Wagner wrote passionately about his desire to create an opera house that had strong ties with Greek theatre.3 Wagner felt the Greek theatre epitomized what great art should accomplish.The experience "was the nation itself—in intimate connection with its own history—that stood mirrored in its art-work, that communed with itself and, within the span of a few hours, feasted its eyes with its own noblest essence" ("Art and Revolution" 52). Thirdly, in Das Bühnenfestspielhaus zu Bayreuth (The Stage Festival Theatre in Bayreuth, 1873), Wagner clearly describes the effect of a renewed spiritual connection with the stage that he hoped his new theatre would provide for his audience. The connection he describes is similar to the type of perception produced by the interaction between visual culture and certain types of spiritual practices that use material objects or settings to produce"religious seeing."

3 While according to the online Richard Wagner Archive, Wagner wrote approximately 230 books and articles in addition to his many operas (Salmi), this paper will draw on only a few of the writings relevant to our discussion, namely: a) Ein Ende in Paris (Death in Paris, 1841); b) Kunst und die Revolution (Art and Revolution, 1849); c) Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft (The Art-Work of the Future, 1849); d) Das Bühnenfestspielhaus zu Bayreuth (The Stage Festival Theatre in Bayreuth, 1873); and e) Religion und Kunst (Religion and Art,1880). Some of these writings are woven into the discussion of the history of western stage design. Each of the five writings is then discussed separately at the end of the section on historical evidence.

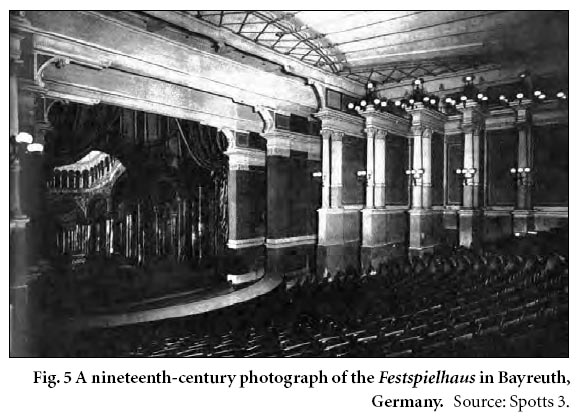

A) Historical Evidence: Western Theatrical Space

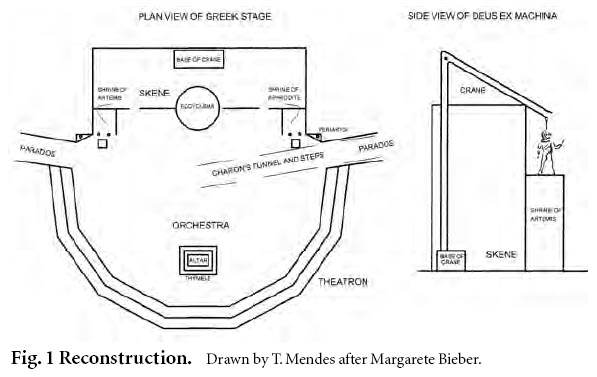

4 The first set of data relevant to our argument consists of an overview of western stage building from the Greek theatre (500-300 B.C.E.) to the Elizabethan stage (1576-1613) to the Hummingbird stage of 2005 in Toronto, Ontario.4 Wagner admired the Greek stage as an ideal space for drama. Describing the power of the Athenians’ use of space when combined with music and voice, in his essay "Art and Revolution" Wagner praised the architectural elements that "joined the bond of speech, and concentrating them all into one focus, brought forth the highest conceivable form of art—the DRAMA" (33). The Greek stage was the first thrust stage known to the world. The plays presented on this stage were religious in nature, performed in honour of the god Dionysos. In the ancient Greek world, the audience and performers shared a communal understanding of the various deity cults and the honour due a god or goddess on their festival day.

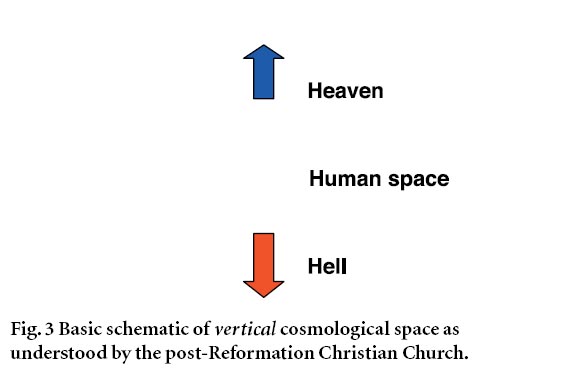

5 The Greek theatres divided the stage into three areas representing a vertical cosmology.The area above the stage was reserved for gods, the stage itself was inhabited by mortals, and traps in the stage led to the underworld [See figure 3 – vertical schematic]. The vertical cosmos was also reinforced through the use of stage machinery. This is most clearly demonstrated in the use of the deus ex machina, which allowed actors to be either lifted up or dropped from above. Julius Pollux writing about the Greek theatre describes the apparatus as follows: "As for the scaffold [mechané] it shows gods and heroes that are in the air (such as Bellerphon and Perseus); and it is fixed at the left avenue aloft above the stage-house" (9). Pollux also describes Charon’s steps, an underground passage, which "are for the conveyance of ghosts" (9). Though actual stage machinery has not survived from the Greek theatres, below is a reconstruction sketch of the deus ex machina exemplifying the hierarchical conception of heaven, earth and the underworld.

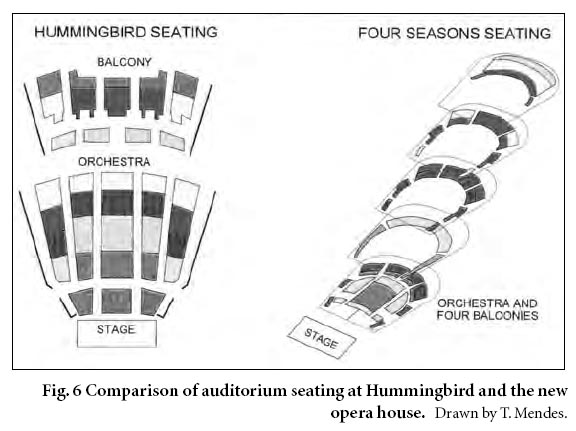

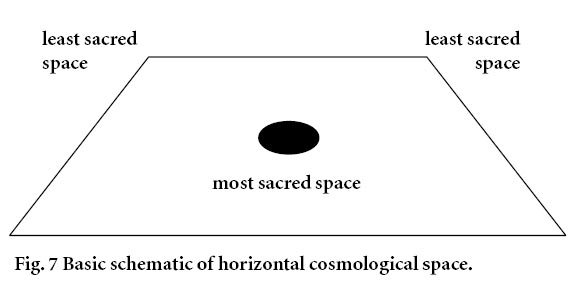

Fig. 1 Reconstruction.

Display large image of Figure 2

6 The Elizabethan thrust stage is considered to be one of the greatest achievements of western theatrical space. Like the Greek theatres this space is vertically cosmological [See figure 3 – vertical schematic]. The introduction of the proscenium arch, begun during the Italian Renaissance for the productions of court masques, was connected to the advent of single-point perspective. The proscenium arch acted as a frame through which the audience watched the stage. The shift from thrust staging to proscenium viewing altered the relationship of the audience to the stage. The audience was now separated from the stage; they became passive viewers rather than actively engaged participants. Wagner’s construction of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, Germany, started in 1872, stemmed from a desire to overcome the barrier created by the proscenium arch. Stage scenery under Wagner shifted from a vertical cosmos to an emphasis on a horizontal arrangement of power. Based on archaeological research of the Viking period conducted by the opera’s designers, Joseph Hoffman and Karl Doepler, the Ring cycle, mounted in Bayreuth in 1876, defined theatrical space as a horizontal cosmos; i.e., supernatural power emanates most strongly from centre stage and becomes increasingly less powerful towards its edges [See figure 7 – horizontal schematic]. This model, used by the designers, actually agrees with the Old Norse religious understanding of the cosmos as suggested by archaeological evidence [See figure 9].

7 While today’s Hummingbird theatre can be read as secular entertainment space, the actual stage structure still retains the memory of vertical cosmological space, part of the legacy of western stage building, handed down by Greek and Elizabethan theatres. Though stage use in contemporary Western theatre is varied, it is not unusual for theatre space to be used with an underpinning of a vertical universe. Gods and angels tend to dwell in the upper reaches of the stage area, humans play their roles on the stage and hell is frequently represented by traps in the stage.

8 It is important to state that the visual evidence we have for the Elizabethan stage is minimal. Johannes de Witt’s sketch of the Swan theatre, drawn in 1596, was accompanied by a written description of the theatre in his diary.The original drawing was lost; what remains is a copy by Arendt van Buchell thought to be made between 1596 and 1598. This evidence is supplemented by archaeological data from the foundation, excavated in 1989, of the Rose theatre built in 1587 by Philip Henslowe. Unfortunately, this information shows the ground plan position of the stage, but does not give details of the actual stage structure.

Fig. 2 Drawing of the Swan theatre, ca. 1598. A copy of original drawing made in 1596.

Display large image of Figure 3

9 Not surprisingly, many of our contemporary ideas regarding theatrical space are based on our understanding of the Elizabethan stage. It is looked upon as the"golden era of theatre"that focused on acting and narrative. As a result we need to look carefully at this space. As stated above,Gary Taylor,writing about Shakespearean productions on the Elizabethan stage, suggests that in this type of theatre "space is cosmic and human: ‘where we are’ is determined by theological architecture and portable accessories" (15). The Elizabethan stage space represented earth, heaven, and hell. Hell was the space under the stage accessible by traps; earth was the main playing area on the thrust stage backed by doors and possibly an inner stage draped in curtains. The canopy or overhang above the stage was called "the heavens." Lorenzo, in Merchant of Venice describing the night sky to Jessica says, "Look how the floor of heaven / Is thick inlaid with patterns of bright gold" (5.1.58-59). The architectural space of the theatre embodied the vertical levels of the cosmos as understood by the predominantly Christian audience.

Fig. 3 Basic schematic of vertical cosmological space as understood by the post-Reformation Christian Church.

Display large image of Figure 4

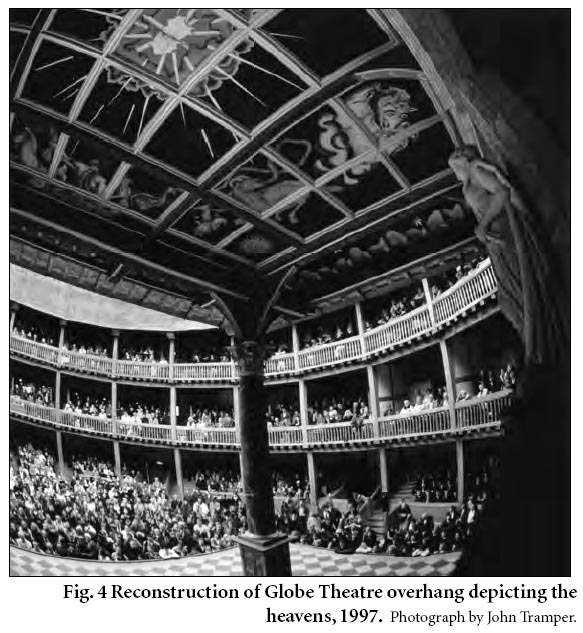

10 The reconstruction of the Globe Theatre in 1997 incorporated colour to indicate the various areas of the cosmos. The playing area of the stage is painted with earth tones: reds, browns and greens. The shade above includes the heavens, which are predominantly blue, decorated with golden sun, stars, moon and symbols of the zodiac. The photograph of the Globe reconstruction, figure 4, shows heaven, above; earth, the place of humans, the mid area; and beneath the stage, hell. The vertical cosmos schematic shown above is directly illustrated in London’s Globe Theatre.

11 The thrust stage surrounded by the audience is one of the most intimate spaces between actors and viewers. The Elizabethan stage used minimal scenic elements to depict locations. The audience understood and accepted partial visual signs.A throne was enough to define the throne room of a king; a lantern represented the moon. Not only did the audience see the cosmos but they were also part of this universe. Staging Shakespeare’s plays in this space was a sculptural three-dimensional activity most closely linked to the staging relationship of audience and actors on the ancient Greek stage.

Fig. 4 Reconstruction of Globe Theatre overhang depicting the heavens, 1997.

Display large image of Figure 5

12 The transformation from the thrust stage into the framed proscenium stage occurred between the closing of Elizabethan theatres in 1642 and the reopening of theatres in 1660. The rising Puritan movement led by Oliver Cromwell in the late 1630s and early 1640s was antagonistic towards theatres in London. Theatres were considered "chapels of Satan." In 1642 the Puritan faction of Parliament wrested control of the city of London and ordered the closing of all theatres. Charles I was tried and executed and Charles II fled to France. When the monarchy was restored in England in 1660, Charles II opened two Restoration stages. Taylor states that "the post-Restoration definition of space was […] Cartesian and Newtonian […]," i.e., scientific. Stock scenes were interchangeable and functional (15). Like the world of science, a taxonomy of stage properties was organized. Trees were recognisably trees. It didn’t matter if the play called for an enchanted forest or a dark forbidding woods. Reusable two-dimensional painted flats became the dominant method of signalling locations. Structurally the proscenium arch defined a line between the viewer and the stage: the audience was on one side and the stage was on the other. From the seventeenth until the early twentieth century, two-dimensional painted scenery became the standard method of denoting location on the proscenium stage. In tandem with the development of painted scenery, auditoriums became progressively more elaborate, dividing the house into many levels and boxes. Although no longer obvious, this new configuration still embedded the staging practices of the sixteenth century, in that its structural design represented vertical space as cosmological. "Up" remained linked to heaven, the place of gods; the stage represented the world of humans; and the space"below"the stage continued to be read as an "underworld" or"spirit world."5

13 Seeking to restore actor-audience intimacy in the last quarter of the nineteenth century,Wagner wanted to create a theatre that would allow the audience, fatigued after their day of toil, to come to the opera for physical and spiritual renewal, to see opera as a place to engage in the "religious seeing" of the world created onstage. According to Wagner in"Art and Revolution,"a revitalized audience could "fuse their own being and their own communion with that of their god; and thus in noblest, stillest peace to live again the life which a brief space of time before, they had lived in restless activity and accentuated individuality" (34). Theological architecture as used in Greek and Elizabethan stages was thus enlisted to these ends. Begun as a temporary space for his Ring cycle, the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth started construction on 22 May 1872. It was built of wood from the area (pine and maple) and shaped with a steeply raked house to ensure good sightlines for everyone in the auditorium. The use of wood to construct the Bayreuth theatre was in part due to the need to economize; however, it also supported Wagner’s desire to construct a temporary structure for his festival. This building provided a stark contrast to the traditional boxed horseshoe auditorium exemplified by the Paris Opera House, designed by Charles Garnier, that opened at about the same time in 1875.

14 The cowled orchestra pit in the Festspielhaus changed the audio and visual presentation of Wagner’s productions.It mixed the sound and dampened the orchestral music, emphasizing the singer’s voice. The musicians’ lights and movement were blocked by the cowl thus minimizing distraction for the audience. Dimming the house lights was another means of focusing the audience’s attention. In The Stage Festival Theatre in Bayreuth, Wagner explains that instead of grand ornamentation in the auditorium, the spectator would "find expressed in the proportions and arrangement of the auditorium and seats an idea,the comprehension of which will at once place you in a new relationship to the drama you will have come to see"in this building (qtd. in Barth, Mack and Voss 221). Wagner attempted to pull the audience back into the onstage world, which although no longer a Hellenistic or Christian cosmos (i.e., in fact it was a horizontal cosmos), retained elements of western sacred space embedded in its structure.The upper reaches of the stage are still associated with gods and heaven, and the area under the stage with the nether-world of Nibelheim.

Fig. 5 A nineteenth-century photograph of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, Germany.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 8

15 Conversely, the Hummingbird Centre (formerly called the O’Keefe Centre from 1960 to 1996) was built to accommodate the need for a large performance space presenting variety of performing arts including ballet, opera, concerts, and plays. However, this desire to use the centre as a multipurpose space ultimately led to dissatisfaction with the building. The major complaints were that many seats were too far from the stage, the balcony was too high, and the acoustics were poor. In 1996, the space was renovated to address these issues of separation between the performers and the audience. Of interest, the visual austerity of the Hummingbird has more in common with the Bayreuth theatre than with the new opera house recently opened in Toronto. Moreover, the new Four Seasons Centre’s auditorium, in which Wagner’s operas are now performed, is a horseshoe structure—the type of opera house Wagner so disliked (see fig. 6).6

16 Based on this brief overview of western stage construction, it is suggested that the reading of theatrical space as vertically cosmological is embedded in the stage architecture at the Hummingbird, although the audience may not always read it as such. However in Levine’s set designs for Die Walküre and Siegfried, vertical space is less important than horizontal space. The penultimate sacred space is located at centre stage and becomes increasingly less sacred towards the stage’s edges as per figure 7.

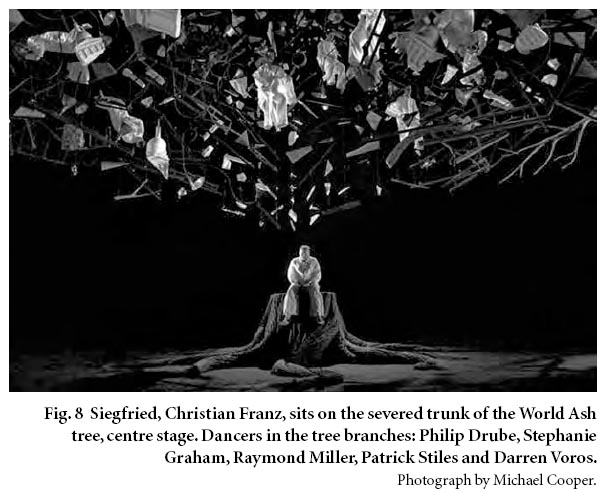

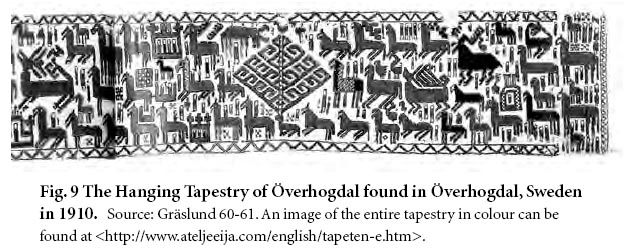

17 An overview of horizontal cosmological space in the COC’s 2005 production of Siegfried using Michael Levine’s sets is shown in figure 8. The model and image of Levine’s set design conform to how pagan north-western Europeans understood their cosmos, as suggested through examples of archaeological finds depicting ancient Norse religion.7 According to Anne-Sofie Gräslund, a professor of archaeology at the University of Uppsala, Sweden,

In Viking Cosmology the world was thought of as being like a flat round plate on which humans and other beings had assigned places. The gods lived in the center of the world in Asgard, around the tree Yggdrasil with humans surrounding them in Midgard; giants lived in Utgard around the outer edges. However, there was some vertical space as well, for the dwarves lived underground and the norns lived among the roots of Yggdrasil. (57)An embroidered tapestry found in the attic of a parish church in Northern Sweden is thought to date to the Viking Age ca. eleventh century.8 Elements of Old Norse cosmology make up its icono-graphic field: The world tree Yggdrasil forms the centre of the tapestry. The eight-legged, shamanic horse (Sleipnir or sliding one) belonging to Odin, the creator of the human race and god of wisdom in Norse religion, is depicted at mid-points between the sacred centre and the edges of the cosmos as though he were midway through a journey.9 The name Yggdrasil means "steed of Ygg," another name for Odin, who was thought to possess shamanic powers through a type of magic called seidur which was mostly practiced by women (Price 70-71). In addition to the idea of the cosmos as horizontal and ring-like, recent scholarship suggests that Norse religion may share the idea of a horse transporting a"seer"to different worlds with other circumpolar cultures including Siberian and Saami religions (Lapp; Price 71). Those, such as Siegfried, who mount the trunk of the World Ash tree, therefore could be viewed as participants in a life-altering shamanic flight. As the central piece of stage architecture in the Ring Cycle, the World Ash tree has strong

ritual overtones, beyond its geographical location at the heart of a horizontal cosmos.10

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 10

18 It is unknown whether Wagner was aware of the Norse shamanic overtones of his Ring cycle. Certainly he was interested in the problematic relationship between history and myth as formulated in his essay, Die Wibelungen: Weltgeschichte aus der Sage (The Wibelungs: World History from Legend, ca. 1849) suggesting that he might have perceived the various sagas behind the Ring as carrying authentic elements of historical religious practices. Typically, Wagnerian scholars do not list art and artefacts from Norse antiquities in their inventory of sources for Wagner’s operas. Further, archaeologists of circumpolar cultures have only recently begun to organize comparative studies of related art and artefacts synchronically, especially those having to do with shamanic practices.11 Nonetheless within the written sources Wagner consulted such as The Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson, references to magic and sorcery exist which today’s anthropologists and archaeologists interpret as "recognized features and functions of shamanism in the circumpolar region" (Price 70). Thus, we propose, whether consciously constructed or not, Levine’s set design still references the horizontal cosmology of ancient Norse religion that was part of Wagner’s research for the operas. Conversely, the Hummingbird stage, marked by the historical formation of the western theatre that defined the theological space of stages, has a vertical cosmology ingrained into the very structure that frames its productions. Levine, working within the boundaries of this frame, managed through his set designs to configure centre stage as the most important theatrical space in the Ring cycle. Our point here is the recognition of theatrical space in Die Walküre (2004) and Siegfried (2005) as cosmological.We will have more to say about the optical illusions presented in the theatrical space of these productions and how the space equally offers a bi-ocular experience of audience seeing (one psychological and one religious) in our section on scenographic evidence below. Before turning to that section, we will conclude our section on historical evidence by briefly examining Wagner’s ideas about the relationship between art and religion.

19 The following brief examination of selected theoretical writings by Wagner on the relationship between religion and art, we suggest, further supports our thesis, that Die Walküre and Siegfried offer an alternative definition of theatrical space as cosmological, whereby visual information and the ideal stage create the conditions for viewer-audience "religious seeing." We suggest that this understanding of theatrical space is integral to Wagner’s own vision of the function of theatre.As such, we can state the following five propositions based on our review of his selected writings as listed above. First, Wagner believed that art proceeded from a supernatural source which ultimately redeemed all humankind; second, that ideal theatre (i.e., Greek-Hellenistic in Wagner’s view), which embodies the necessary raw elements such as love of nature, an ensemble of voice, sculpture, music, chorus and acting needed to create art, brings the audience together as a community "in a communion with that of their god." Third, that audience members need to be an active community united with the performers onstage. Fourth, that the images created by theatrical space should function to renew the audience’s cosmological connection with life itself and, finally, that art, by engaging the viewer’s imagination, can indeed lift itself (and the viewer) into the realm of revelation.

20 The first proposition, that Wagner believed art proceeded from a supernatural source which ultimately redeemed all humankind, is clearly demonstrated in his Ein Ende in Paris (End in Paris, 1841), a short story in which a young German composer, hoping to make his mark in the world of opera (not unlike Wagner),dies an untimely death in Paris due to hunger,rather than compromise his art.Wagner, in this story, sets out his own creed to art in his character’s dying words:

I believe in God, Mozart and Beethoven, and likewise their disciples and apostles;—I believe in the Holy Spirit and the truth of the one, indivisible Art;—I believe that this Art proceeds from God, and lives within the hearts of all illumined men;—I believe that he who once has bathed in the sublime delights of this high Art, is consecrate to Her for ever, and never can deny Her;—I believe that through this Art all men are saved, and therefore each may die for Her of hunger;—I believe that death will give me highest happiness;—I believe that on earth I was a jarring discord, which will at once be perfectly resolved by death. I believe in a last judgment, which will condemn to fearful pains all those who in this world have dared to play the huckster with chaste Art, have violated and dishonoured Her through evilness of heart and ribald lust of senses;—I believe that these will be condemned through all eternity to hear their own vile music. I believe, upon the other hand, that true disciples of high Art will be transfigured in a heavenly fabric of sun-drenched fragrance of sweet sounds, and united for eternity with the divine fount of all Harmony.—May mine be a sentence of grace!—Amen! ("An End")Geoffrey Skelton in "The Idea Of Bayreuth" states that the above text is a nascent form of Wagner’s own growing creed on the relationship between the divine and art (392). Indeed anyone familiar with the Apostles’ Creed, the basic creed of Reformed churches, will immediately recognize it as the thinly disguised template for Wagner’s Artist’s Creed written when he was a young man in Paris in search of recognition and fame.12

21 We find the second proposition demonstrated in Wagner’s essay Die Kunst und die Revolution (Art and Revolution, 1849). In this essay, Wagner expressed his desire to create a place for opera that had strong ties to ancient Greek theatres, places which he thought embodied the raw elements listed above needed to create art. In such a theatre, as we already pointed out, the audience was brought together as a community "to see the image of themselves, to read the riddle of their own actions, to fuse their own being and their own communion with that of their god; and thus in noblest, stillest peace to live again the life which a brief space of time before, they had lived restless activity and accentuated individuality" (34).

22 Writing in Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft (The Art-Work of the Future, 1849) Wagner asked the architect of his ideal theatre to serve two primary needs of the audience. The first was "that of giving and that of receiving which reciprocally pervade and condition one another" (184). Second was the imperative that the layout of the auditorium space enhance the viewers’ "optic and acoustic understanding of the artwork" (185). Thus, the ideal theatre in Wagner’s mind should promote the audience members’ ability to be active participants united with the performers onstage as suggested in our third proposition: The relationship between the house and stage should, in effect, facilitate the audience’s full ability to engage with the scenes optically.

23 In his essay on Bayreuth, Das Bühnenfestspielhaus zu Bayreuth (The Stage

Festival Theatre in Bayreuth, 1873), Wagner clearly describes the effect of a renewed spiritual connection with the stage that he was hoping to achieve for the audience:

Between him and the picture to be looked at there is nothing clearly discernible, instead, only a shimmering sense of distance… in which the remote picture takes on the mysterious quality of a dream-like apparition, while the phantasmal sounding music from the ‘mystic gulf’, like vapours rising from the holy womb of Gaia beneath the Pythia’s seat, transports him into that inspired state of clairvoyance in which the visible stage picture becomes the authentic facsimile of life itself. (qtd. in Spotts 52)That the images created by theatrical space should, according to Wagner, function to renew the audience’s cosmological connection with life itself, our fourth proposition, is similar to the type of perception produced by the interaction between visual culture and certain types of spiritual viewing practices that use material objects or settings to produce the effect of "religious seeing." According to David Morgan, set designs, including costumes and atmospheric effects, can create an environment with the potential for triggering viewer transformation or "religious seeing," through referencing "historical associations and cultural practices" (Sacred Gaze 3), whether audience members are conscious of such viewing practices or not.13

24 Finally with regard to our fifth proposition concerning Wagner’s understanding of the relationship between religion and art (that art, by engaging the viewer’s imagination, can indeed lift itself (and the viewer) into the realm of revelation), Wagner declares in Religion und Kunst (Religion and Art, 1880), that "Art grasps the Figurative of an idea, that outer form in which it shews itself to the imagination, and by developing the likeness […] into a picture embracing in itself the whole idea, she lifts the latter high above itself into the realm of revelation" (216). Art, especially music, was his religion.As a believer in what he calls"true idealistic art" Wagner wrote about art’s capacity to improve upon nature (216), its capacity for redemption (219), and its capacity for transcendence. Wagner thought that belief systems, especially "[Christian] myths [had] defaced the dogma of the Church with artificiality, yet offered fresh ideals to Art" (216). Dogmatic Christianity was an attack on nature’s laws, human perception and even the will to live.Although Wagner believed that visual art "was destined to reach its apogee in its affinity with religion," art had been thwarted in this goal because of its severed connections with religion and therefore had"fallen into utter ruin"(222).Only music or what Wagner called the "Art of Tone" still held out any hope for saving "the noblest heritage of the Christian idea" (224) due to its "pure Form of a divine Content freed from all abstractions" (223).

25 Based on the above references to Wagner’s ideas on the relationship between religion and art, we suggest that this understanding of theatrical space as cosmological and the viewer-audience’s connection with the stage as spiritual or what we today call "religious seeing," is integral to Wagner’s own vision of the ideal function of theatre. We now turn to our discussion on scenographic evidence and how the definition of theatrical space and the set designs of Michael Levine offer a bi-ocular experience of seeing (one psychological and one religious) similar to the face/vase optical illusion with which this article began.

B) Scenographic Evidence for Die Walküre and Siegfried14

26 In this section we suggest that Michael Levine’s own artistic style and scenographic vision in Die Walküre and Siegfried lends itself to the perception of theatrical space as divinely ordered. As such, his set designs, seen as ‘theological architecture,’ signify the spatial location of gods, humans, and mythological creatures. Our discussion focuses therefore on how Levine’s sets theatrically position characters and spectators to perceive the alternating optical illusion of theatrical space as divine (i.e., cosmological) and/or human (i.e., psychological) through Levine’s use of perspective, lighting, symbolic colour, and form.

27 We argue that through the use of perspective, lighting, symbolic colour, and form, Levine disables the spectator’s habits of ordinary seeing to enable in the audience what we suggest is a form of "religious seeing." To recall, "religious seeing," according to S. Brent Plate is an interactive process, an active exchange between that which is seen and the person or persons doing the looking. Further, the perception of how space is constituted, whether secular, cosmic or somewhere in between, is conditioned by one’s own understanding of how the divine (however defined) is envisioned. For example, some religions, especially indigenous types of spirituality, constitute all space as sacred in contrast to western traditions, such as Judaism and Christianity, which define space by degrees of sacrality. If one does not believe in any type of supernatural power that governs the lives of humans and/or the process of creation, then space of any kind will not be perceived by the viewer as potentially sacred.According to Plate, the perception of space as sacred is triggered and reinforced externally in the material world by human-made visual culture (e.g., art, clothing, architecture, icons, etc.) produced within specific religious traditions. While theatrical space is generally not considered to be sacred by most theatre-goers, western theatre does have a theological cosmology embedded into its structure as we have demonstrated. And as discussed above, visual culture including set designs, costumes, and atmospheric effects, can create an environment with the potential for triggering viewer transformation or "religious seeing," whether or not audience participants are aware of such shifts in perceptions.

28 Michael Levine is a designer who makes use of visual space to create unusual ways of seeing. His varied opportunities to design in many countries have helped forge a distinctive visual vocabulary.15 When we go to the theatre or opera we are often being challenged to look anew or differently at a work that has been performed many times. This is particularly true of Levine, whose work is contemporary; his designs do not use traditional or instantly recognizable patterns of realism. Recognizable images are abstracted into poetic visual metaphors as the designer himself suggests in a discussion of Siegfried as a continuation of the narrative in Die Walküre:

With that in mind, we have created something that is a reflection of both a ‘memoryscape’ and a psychological fairytale. Magical things take place and you don’t want to destroy the magic of the piece by conceptualizing to the point of suffocation. But then you also have to re-imagine some of the challenges of the piece.(Levine qtd.inVanstone, "Siegfried" 1; emphasis added)

(i) Changing perspectives

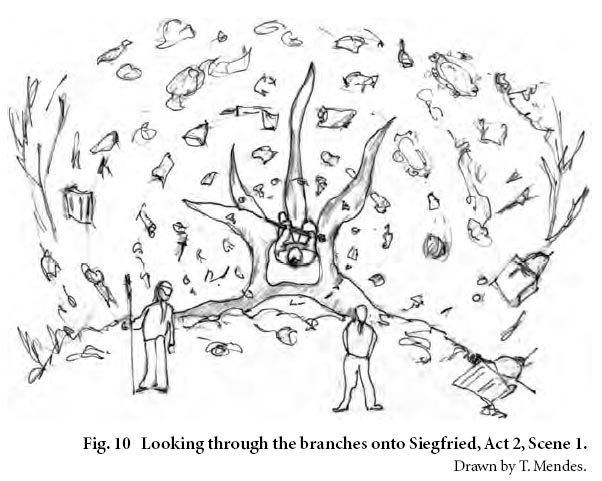

29 To achieve his desire to "re-imagine" the space and the audience’s visual perception of the opera, Levine employs the use of varied perspectives in Siegfried. In Act 1 we see a frontal view of a chopped tree trunk with sprawling roots [See figure 8]. Sitting on the trunk is Siegfried and above his head are branches defined by fragments and bodies. In Act 2, Scene 1 by repositioning the trunk, Siegfried and the tree fragments, the audience is looking through the branches down onto Siegfried sitting on the trunk holding his sword Nothung [See figure 10]. During this scene in Siegfried, we are presented with two angles of vision superimposed on one another. One angle positions the viewer looking down onto Siegfried’s head as he sits on the tree trunk holding his sword. Countering this bird’s eye view is a second perspective that places the Wanderer and Alberich in front of the top of the tree in a vertical, full frontal position to the viewer. In the first perspective, the visual space can be read as two characters flying over or floating horizontally above the tree; in the second perspective, the two characters can be read as walking on the floor of vertical cosmological space, with the tree and Siegfried seemingly floating behind them in space. Thus in this scene, Levine stages the action as occurring simultaneously in horizontal and vertical cosmological space, allowing the viewer to shift back and forth between the two definitions of theatrical space as desired.

30 In Act 2, Scene 2, the shift in lighting emphasizes the fragments in concentric rings as the mouth of Fafner’s cave, and we return to a frontal view where the floor is now simply the floor and not the floor/sky.

31 In contrast, the set in Act 3 is barren, the tree trunk and the fragments are stripped away, Levine’s changed perspective perhaps reflecting the intellectual shifts in Wagner’s own sense of Siegfried’s fate.Wagner wrote Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, and the first two acts of Siegfried from September 1853 to July 1857. He then interrupted the Ring composition for twelve years. In March 1869, he resumed composing Siegfried Act 3, which he finished in June of that year. In an early draft, Wagner had seen Siegfried’s death as a glorious ending where he would be greeted by Wotan in Valhalla. During the ensuing years Wagner’s vision changed to a doomsday myth where gods and mortals alike are destroyed. Levine’s final and severe perspective shift creates the conditions for "religious seeing" in the viewer, thus supporting Wagner’s desire to transport the audience "into that inspired state of clairvoyance" (qtd. in Spotts 52).

(ii) Directing the attention of the spectator

32 David Finn’s lighting for Siegfried amplifies Levine’s visual poetics by never allowing the audience to be aware of a horizon line. Audience members cannot see where the floor ends and the sky begins. The absence of this basic visual key for locating oneself in the onstage world is a deliberate choice by the creative team. Without a horizon line the viewer is without his/her usual understanding of vertical cosmology. We cannot easily determine where the edges of the stage are. The lack of a horizon line helps build the optical illusion of an enormous space, of a pre-Christian cosmos that by its lack of colour, murkiness, and fragmentation allows the audience to hypothesize the area as cosmological, as psychologically interior space, or possibly as both.

Fig. 10 Looking through the branches onto Siegfried, Act 2, Scene 1. Drawn by T. Mendes.(iii) Playing with different time periods: costumes

33 Levine’s interest in mixing different historical periods is apparent in the costume designs for Die Walküre and Siegfried. Using period silhouettes from the 1870s for the Valkyrie costumes links the opera to a particular time period. The choice to have the corsets visible alerts the audience that the costumes are not historically accurate. Nevertheless, the white detailing on the corsets suggests armoured breastplates that evoke traditional images of the Valkyries. The fan-shaped detail on the corsets echoes the truss structure of the set while also evoking the skeletal framework of a tree, subtly referencing the central image of the World Ash tree or Yggdrasil. Meanwhile, Sieglinde, wearing a twentieth-century military overcoat, draws connections to both World War I and II. Employing costumes from different periods suggests that time is not linear in this onstage world.

34 In Siegfried almost all the characters, save Brünnhilde, are in loose-fitting, white pyjamas presenting strong images of sleep and dreams, a clear reference to psychological interior space. However, from the 1920s onward, pyjamas were cut and styled very similarly for men and women, creating both gender and temporal ambiguity through costume. Thus these outfits in Siegfried further convey a place outside of time, i.e., cosmological space.

(iv) Disrupting the spatial order

35 The first strains of music we hear in the prelude of Siegfried are slow, subdued and disquieting. At the top of the act we see what appears to be a large root snaking under the curtain. The light is dim and it is difficult to discern exactly what we are seeing. As the curtain rises we see a most startling tree, a tree of fragments, the World Ash Tree damaged but still growing. Siegfried seated on the severed trunk directly beneath the fragments implies the tree is growing out of his head. The decay of the World Ash began when Wotan broke a branch from the tree to inscribe runes of sacred knowledge [See appendix 1].

36 Wotan paid the price for the knowledge with one of his eyes and ultimately the downfall of the gods. Wotan’s vision and his perspective on the cosmos are changed by the knowledge from the tree. Through acquiring his spear from Yggdrasil, Wotan also attains shamanic powers. Viking shamans, as discussed by Price, have the ability to divine the future; Wotan now knows how the world will end. By the third opera, Wotan realizes he cannot alter the future fall of the gods. In Siegfried, Wotan calls himself the ‘Wanderer,’ acknowledging his unstable and non-stationary place in the universe long after his powerful "Valhalla" days of Das Rheingold.

37 The fragments in the tree contain few actual tree branches, but instead range from larger fragments of classical buildings with pillars, cupolas, and pediments to sleeping people. Some of the smaller items are made of metal and take longer to decipher visually. The first general image is a tree, yet as the opera progresses the individual objects are seen; the tree is also composed of Victorian domestic artefacts: a brass hand bell, a set of silver serving tongs, a pewter plate, a broken silver candelabra, a shiny crucifix, silver ewers, a gold crown, a salt cellar, wine goblets, serving trays, mirror frames, and tiles from Valhalla. Juxtaposing a shiny crucifix against the tiles of Valhalla is a subtle reference to horizontal and vertical cosmologies. Thus, the set designs again simultaneously offer the viewer two different perceptions using the same visual information: one of a tree and the other, the future destruction of the gods’ home in Götterdämmerung.

38 In Die Walküre, the skewed, tilted angles of metal truss and industrial lights suggest a confused, falling and chaotic cosmos. Here we are presented with the World Ash tree in an earlier stage of decay; the tree has recently been chopped down and we see its fallen trunk still leaning on its stump. The tree appears to have grown through the floor, forcing the tiles of Valhalla aside. Tree leaves are metaphorically suggested by the lacy overlapping triangles of the metal truss. Here again, we are seeing concurrently the hall of Valhalla and the eventual collapse of the hall.

39 The destabilized space in Die Walküre also compresses present and future time, a dynamic effect of shifting perspectives that denotes cosmological as well as psychological space. While we watch the Valkyries collect fallen heroes to take to Valhalla, in present time we also see the trunk that will be cut into logs to burn Valhalla to the ground. For many audience members, the knowledge of how the opera ends forces them to confront the multivalent images they are seeing in the context of the whole. In all the above ways, spatial and temporal instability are used both as a means of prompting the audience to look with new eyes at an opera that has been performed many times and also as a way to foreshadow the ending of the opera.

40 As suggested above, Michael Levine’s sets create both bi-ocular visual experiences for the spectator,such as the one discussed in Act 1, Scene 2 of Siegfried, as well as a multivalent theatrical space that seems to exist simultaneously inside and outside of time,such as the Act 3 pyjama costumes in Siegfried or the compressed times of present and future in Die Walküre. While not denying Girard and Levine’s definition of theatrical space as psychological as evidenced by their dream-like scenes and costumes, Levine’s sets also prompt a form of "religious seeing" by the audience based on visual information that configures space and time cosmologically.

Conclusion

41 From the above historical and scenographic evidence, the following conclusions can be drawn. The Greek and Elizabethan stages used an abbreviated and open scenic system. On the Elizabethan and Greek stages, the playwright and audience shared the same orientation to a divine world order. They interpreted objects on the stage in a similar way because the vertical cosmos was the foundation of "religious seeing." This worldview was built right into the structure of the western stage. By contrast,Wagner’s adoption of ancient Norse religion for his Ring Cycle resulted in the creation of a new type of sacred space on the western stage: the horizontal cosmos. Finally, looking at stage images created by set and costume design can be considered as a type of "religious seeing," even when the visual exchange takes place in a secular public space, if the viewer-audience is prompted by optical illusions and relevant images that evoke historical memory of religious practices.

42 In conclusion, Levine’s scenographic work asks for an interactive exchange between audience and performers much in the same way Wagner believed the ideal theatrical experience should unfold for the viewer. Whether that world occurs within the psychic framework of a character’s mind or within a cosmological space peopled with gods and goddesses is ultimately up to the spectator’s perception of the onstage world. The stated decision to set the opera in the mind of Siegfried is certainly one that accords with our contemporary, allegedly secular, personality-driven culture. Nonetheless as we have shown, thanks to Levine’s set designs, two equal and alternating readings of the theatrical space (one psychological and one religious) are possible.

43 As we have argued in this paper, both Die Walküre and Siegfried provide spectators with a richer viewing experience when the dramatic action is read as occurring both within the cosmos of ancient Norse religion and/or inside the head of Siegfried. Granted, drama viewed within the interpretive frame of psychological interior space can provide an important self-reflective experience for the audience. However it can also throw the spectator back on him/herself to construct what is ultimately an alienating and wretched understanding of one’s own existence.Through a viewing position which includes an alternating perception of these operas as both psychological and/or "religious seeing," the world onstage can also construct the spectator as a social subject, whose choice of transcendent viewing, while perhaps no longer triggered by a divine power, as Wagner would have it, at least assures the audience of a place within the human community, i.e., as a co-participant in the human process of creation.

Appendix 1: Brief Outline of Ring Cycle

44 Before Das Rheingold begins, in his search for knowledge Wotan (Gemanic name for Norse god known as Odin), father of the gods, acquires his spear from Yggdrasil, the World Ash Tree. He pays for this knowledge with the loss of one of his eyes. Taking the branch from the World Ash Tree causes the tree to begin to wither.

45 In Das Rheingold, the gods have recently had Valhalla built by the giants who are looking for their promised payment. Wotan tricks Alberich out of the gold and the ring he stole from the Rhine maidens and uses this to pay the giants.

46 Die Walküre commences with Siegmund and Sieglinde, twins separated at birth, meeting and falling in love. Though protected by Brünnhilde, Siegmund battles with Hundig and is killed. Sieglinde now carrying Siegmund’s child (Siegfried) escapes. Wotan, angry that Brünnhilde disobeyed his orders not to protect Siegmund, takes away her godhead and surrounds her in a ring of flames. She sleeps awaiting a hero to wake her.

47 In Siegfried, the hero,raised by the dwarf Mime,needs a sword to go out into the world. Siegfried reforges his father’s sword, kills the dragon,and acquires the ring.The Wood Bird leads Siegfried to Brünnhilde sleeping in her ring of fire. Kissed by Siegfried, she awakes and they fall in love.

48 In the final opera, Götterdämmerung, Siegfried, deceived by a potion prepared by Hagen, forgets Brünnhilde and falls in love with Gutrune. He then helps her brother, Gunther bring Brünnhilde to the hall to marry Gunther. In anger Brünnhilde reveals that the one place Siegfried is unprotected is his back. Just before Siegfried dies, stabbed by Hagen in the back, he remembers his love for Brünnhilde. Taking the ring from Siegfried’s dead hand, Brünnhilde signals to Wotan to burn Valhalla. She prepares the funeral pyre for Siegfried and joins him. The final image is of the gods sitting in Valhalla burning.

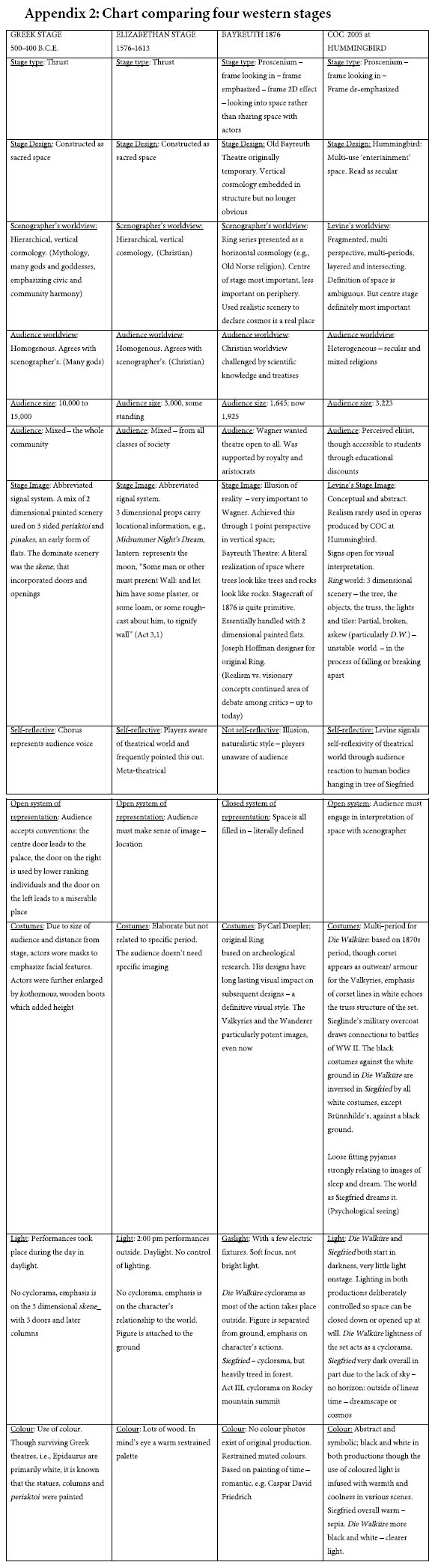

Appendix 2

Chart comparing four western stagesWorks Cited

Barth, Herbert, Dietrich Mack, and Egon Voss, comps. and eds. Wagner: A Documentary Study. London: Thames and Hudson, 1975.

Bieber, Margarete. The History of the Greek and Roman Theater. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1961.

Everett-Green, Robert."Journey to the centre of Siegfried’s Mind." Globe and Mail 27 January 2005: R3.

—."A fascinating Siegfried of the mind." Globe and Mail 29 January 2005: R7.

Fitzhugh William W., and Aron Crowell, eds. Crossroads of Continents: Cultures of Siberia and Alaska. Washington: Smithsonian Institution P, 1988.

Fitzhugh, William W., and Elizabeth I. Ward. Vikings: the North Atlantic Saga. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution P, 2000.

Gräslund, Anne-Sofie. "Religion, Art, and Runes." Fitzhugh and Ward 55-69.

Izenour, George. Theatre Design. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977.

Leacroft, Richard. Theatre and Playhouse: An illustrated Survey of Theatre Building from Ancient Greece to the Present Day. New York: Methuen, 1984.

Morgan, David. The Sacred Gaze: Religious Visual Culture in Theory and Practice. Berkeley: U of California P, 2005.

—. Visual Piety: A History and Theory of Popular Religious Images. Berkeley: U of California P, 1998.

Nancke-Krogh, Søren. Shamanens hest : tro og magt hos vikingerne. København K : Nyt Nordisk Forlag Arnold Busck, 1992.

Nicoll, Allardyce. The Development of the Theatre: A Study of Theatrical Art from the Beginning to Present Day. London: George G. Harrap, 1927.

Plate, Brent S., ed. Religion, Art and Visual Culture: A Cross-Cultural Reader. New York: Palgrave, 2002.

Pollux, Julius. "The Parts of the Theatre." A Source Book in Theatrical History. Ed. A.M. Nagler. New York: Dover, 1952. 8-10.

Price, Neil S. "Shamanism and the Vikings?" Fitzhugh and Ward 70-71.

—. The Viking Way: Religion and War in Late Iron Age Scandinavia. Uppsala: Dept. of Archaeology and Ancient History, 2002.

Renaud, Jean. Les dieux des Vikings. Rennes (France): Ed. Ouest-France, 1996.

Salmi, Hannu. The Richard Wagner Archive. 31 July 2006 http://users.utu.fi/hansalmi/wagner.html.

Shakespeare,William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Leah S. Marcus. New York; London: W.W. Norton, 2006.

Skelton, Gary. "The Idea of Bayreuth." The Wagner Companion. Eds. Peter Burbidge and Richard Sutton. New York: Cambridge UP, 1979. 389-411.

Spotts, Frederic. Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1994.

Taylor, Gary. Reinventing Shakespeare: A Cultural History, from the Restoration to the Present. New York: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1989.

Vanstone, Suzanne. "Girard Welcomes Siegfried." Prelude: The Voice of the Canadian Opera Company, 2004/2005 Season. Mississauga: Entis Communications Group Inc., 2004. 42-44.

—. "Siegfried: A Psychological Journey." Prelude: The Voice of the Canadian Opera Company, Winter 2005. Mississauga: Entis Communications Group Inc., 2005. 1.

Wagner, Richard. "Art and Revolution." Trans. William Ashton Ellis. Prose Works Volume 1. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd., 1895. 23-65.

—. "An End in Paris." Trans.William Ashton Ellis. The Wagner Library, Edition 1.0.Website established in 2001. http://users.belgacom.net/wagnerlibrary/prose/wagendpa.htm.

—. "The Art-Work of the Future." Trans. William Ashton Ellis. Prose Works Volume 1. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1895. 69-213.

—. "The Stage Festival Theatre in Bayreuth." Barth, Mack, and Voss 221-22.

—. Religion and Art. Trans. William Ashton Ellis. Lincoln and London: U of Nebraska P, 1994. Reprinted from the original English translation of Volume VI (Religion and Art) of Richard Wagner’s Prose Works, published by London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1897.

Notes