Articles

In the Habit of Independence:

Cross-border Politics and Feminism in Two World War I Plays by Sister Mary Agnes1

Kym BirdYork University

Abstract

This article examines the life and playwriting of Sister Mary Agnes who wrote a large oeuvre of plays, largely for girls, while living and working in Winnipeg’s St. Mary’s Academy between 1909 and 1928. It examines her biography, religious order, and professional work in order to elucidate the bold political positions expressed in two of her plays, "A Patriot’s Daughter" and The Red Cross Helpers: A Patriotic Play. It endeavours to answer the question, what made it possible for a Catholic nun living in the heavily charged political environment of Winnipeg at the time of the First World War to express views that were contrary to that political environment and to do so in plays for young high school girls?Résumé

Cet article porte sur la vie et les œuvres dramatiques de Soeur Mary Agnes. Entre 1909 et 1928, Soeur Agnes a vécu et travaillé à la St. Mary’s Academy à Winnipeg. C’est durant cette période qu’elle a composé un grand nombre de pièces de théâtre destinées surtout aux filles. Cet article analyse sa vie, sa congrégation religieuse et son travail professionnel afin d’illustrer les positions politiques hardies exprimées dans deux de ses pièces : « A Patriot’s Daughter » et The Red Cross Helpers : A Patriotic Play. L’objectif de cette étude est de répondre à la question suivante : comment expliquer qu’une religeuse catholique vivant dans l’atmosphère politique tendue de Winnipeg à l’époque de la Première Guerre mondiale soit capable d’exprimer des opinions allant à l’encontre des politiques de la période et de le faire par le biais d'un théâtre pour jeunes collégiennes?1 Sister Mary Agnes wrote more plays in Canada than did any woman of her generation. She published and performed by far the greatest majority in Winnipeg at St. Mary’s Academy, a long-established Catholic girls’ school, run by the Quebec Order of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary to which she belonged. One source estimates she penned nearly 70 plays.2 This, in and of itself, is genuinely remarkable. What is even more remarkable is the fact that two of these plays, "A Patriot’s Daughter" and The Red Cross Helpers: A Patriotic Play, works that bookend the First World War, are politically charged theatre that put her directly at odds with the dominant community in Winnipeg at the time. The content of both plays is provocative because of the ways in which it critiques or dismisses the British Empire, unabashedly celebrates American ideology, and endorses a woman-centred view of the world.

2 What made it possible for a woman living in Canada in this social and political climate to voice such adversarial, potentially volatile views in plays that were written to be staged by high-school-age girls? To understand what liberated Sister Agnes to write such plays is to imagine the complicated social, political, and religious location she occupied and how it positioned her as an outsider in Winnipeg. She was an American-born Irish-Catholic nun married to a French-Canadian order. She remained an American citizen all of her life. Given that both Irish-Catholic and American histories have been formed, to a great extent, out of their resistance against the British, Sister Agnes would have been well versed in the discourses of political independence and understandably alienated from British-identified, Protestant-run Winnipeg during the First World War. A missionary who stayed relatively briefly in most places, she was always an outsider, living in semi-seclusion in the all-female community of a convent. Her sense of autonomy and entitlement to express herself was fostered by this unique environment. In Winnipeg she lived in pastoral, privileged Crescentwood, where she rose to the highest ranks of her profession, teaching university courses and mentoring the daughters of Winnipeg’s first families to enter a social and professional milieu that produced the most successful suffrage movement in the country. Her literary voice and career were condoned by her order and her plays were recognized by them as part of her religious obediences.

3 While her American, Irish, and Catholic allegiances positioned Sister Agnes in opposition to the dominant majority, it was the fact that she lived in Canada, a political context that contradicted these allegiances, I would suggest, that motivated her dissenting voice. It was the unreserved endorsement of her dramas by her order that authorized that dissent and inspired her to place it in the mouths of women characters.

4 She was born Mary Ives on 20 July 1862 in south Boston, Massachusetts. Her parents, Edward and Elizabeth (nee Hall), and her grandparents were also born on the eastern seaboard. Her allegiance to the United States, her affinity with its history and the principle of liberty and independence, as well as its deep aversion to the British, were inculcated and sustained by her Irish heritage in Boston. Her forbearers likely immigrated to America from Ireland in the eighteenth century during the brutally suppressive British Penal Laws and may very well have participated in events associated with the War of Independence, which was of course America’s great war against Britain (Ignatiev 34).3 For her immediate family, America had lived up to the individualistic rags-to-riches mythology upon which it was founded. Her father Edward was a successful broker and her mother "Lizzie" was in possession of her own substantial inheritance, as her father had been a merchant of some wealth.4 Of course, this was not the case for the majority of the Irish working class in the eastern United States, some of whom her family knew intimately. She was exposed to more recent news of the plight of the Irish under British rule by the three live-in Irish immigrant servants whom her family employed.5 As an educated Irish girl in Boston, the heartland of American independence, Mary Ives would have been well schooled in anti-British feeling, especially as it had been amply rekindled during the Civil War, the cancellation of the free trade treaty with British North America (1854), and the Fenian Raids into Canada (Jones 240; Hux, Jarman, and Geberzon 288).6

5 The Order of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary to which Sister Agnes belonged was French Catholic. Founded in France and imported to Canada, it was also the product of a society that was built in opposition to the British in North America.7 According to Marta Danylewycz, the rapid and extensive expansion of such orders during Sister Agnes’s lifetime grew with the general expansion of the church during "the conservative climate that permeated the Union period" (21). They were "part of the Catholic Church’s response in Quebec to urbanization, industrialization" and were affected deeply by the "French-Canadian fear of assimilation" under the rule of the British (21-22, 50).8 Assuming the Holy Names shared this fear, Sister Agnes’s American and Irish animosities toward the British would have been significantly enhanced by her French-Canadian order and its common history of fear and oppression under British cultural domination. Despite the fact that she herself was neither French nor Canadian, Sister Agnes’s location as an outsider in Canada, however, did not turn solely on the fact that she was an Irish-American Catholic in a French order. It also pivots on the fact that she saw herself, fundamentally, as a missionary, a calling she prized above all others. "Missionaries," she once said, were "the greatest heroes of the world" ("Obituary"). Like all missionaries, she was a kind of professional outsider, one who was "sent out" eleven times by her order. She was just eighteen years old when she left Boston to study at Hochelaga Convent in Montreal. After three years of what was the equivalent of "normal school" she received her graduation medal. On 6 August 1883 Mary Ives became Choir Sister Mary Agnes, a Holy Names novitiate. She learned the rules and customs of her order at the Holy Names Academy in Albany, New York (1884-89) where she spent her probationary period. 9 She then took her final and perpetual vows and was relocated back to Hochelaga Boarding School: her alma mater was her first teaching assignment after being admitted into the profession (1889-91). She taught in half of the Order’s "provinces," among them, New York (which included Florida), Montreal, Ontario (which included Detroit), and Manitoba. After a year in Beauharnois, Quebec (1891), she was posted to Windsor, Ontario (1892-94), the administrative headquarters for houses in Windsor, Sarnia, Amherstburg, and Detroit, no doubt to groom her for the significant administrative challenges that lay ahead. It did not take long for her to distinguish herself as one of the Order’s ambitious bright lights. In 1894, at the age of thirty-two, she was appointed Principal of the Academy of Holy Names in Rome, New York (1894-99). Five years later she was called to replace the position of Principal in Key West (1899-1905): she was responding to the epidemic of yellow fever there, in which a number of nuns died while tending the sick. Her tenure involved overseeing a huge capital project that became "the handsomest educational building in the State of Florida (Malloy 28; Browne). In 1905 she returned to Canada for good. She became "one of the foundresses of Outremont Convent," but remained there only one year before undertaking another short post at Outremont Boarding school (1905-07). She briefly returned to Hochelaga (1907-09) before she was given her final obedience in Winnipeg at St. Mary’s Academy. In all likelihood, therefore, Sister Agnes was rendered an outsider by her role as missionary, which would have denied her a deep bond with any specific geographical location other than the New England of her childhood. Insofar as she enjoyed no real attachment to the physical places in which she lived and worked as a nun, and therefore no profound duty or loyalty to the local politics associated with such places, she would be made even more independent to pursue her writing and ideas in the context of her Order, religious duties and profession. By the time she settled in Winnipeg, Sister Agnes was almost fifty years old and at the height of her creative and professional potential. And even though she served the Catholics of Winnipeg for the next two decades and for the duration of her professional life as a teacher, she was never truly of them.

6 Winnipeg, the backdrop against which Sister Agnes lived the most productive years of her life as a playwright, had its own particular set of alienations which cast her further as an outsider. In the second decade of the twentieth century, it was a burgeoning city, the third largest in the country. It was dubbed"the Chicago of the North," but from the perspective of the Holy Names nuns at St. Mary’s, it was dirty, poor, and full of foreigners. Winnipeg’s increasingly rough inner city, along with the need for more space, was central to St. Mary’s decision to move to the more pastoral, soon to be refined, reaches of Crescentwood on the edge of town (Rostecki and Ritchie 39).10 Sister Mary Gorman, the archivist at St. Mary’s Academy, is sure Sister Agnes would have considered Winnipeg a hardship post: "if only for the weather" (interview). After living in Florida this is perhaps understandable. And after Boston, Albany, and Montreal, Winnipeg must have seemed to her an island of strangers on the edge of nowhere. Mass immigration, mostly from central Europe, tripled its population in twenty years. Its rapid industrialization and urbanization produced a cascading set of social problems, including a shortage of housing, sanitation, clean water, public health, and education. Winnipeg was an English city that identified with Protestantism, which meant that Catholics, who were historically French-identified, were firmly marginalized, a situation that only intensified during the First World War.11 Its ruling elite were identified with Canada, Britain, and the Empire and it eagerly joined with most of the rest of the country in its support of the War, whereas its French Catholics were influenced by the views of Henri Bourassa (1868–1952), who regarded the War to be a foreign, Imperial affair and who believed that Canada’s role in it, were it to have one at all, should be defense at home (Cook 402-3).

7 In Winnipeg at the time, there was also a fairly strong anti-American sentiment of which Sister Agnes—as an American— must have been aware. Americans made up its "largest single group of unnaturalized residents" when they"began to pour north of the border" after the turn of the century (Thompson 83). In industrialized Winnipeg, some believed, the preponderance of Americans threatened to bring about free-trade and even annexation. It was a fear significant enough to be entertained in Parliament, which "was warned that a virtual American state was being established" there, and one which would have marked Sister Mary Agnes as Other purely because she identified as an American (Thompson 83).

8 Another particular tension that likely made an impact on Sister Agnes’s location as an outsider was the Manitoba Schools Question, the ground upon which the fin-de-siècle battle between French and English was fought. Conducted in Winnipeg, it pitted the English against the French, the church against the state, and schools like St. Mary’s against Protestants schools. The Schools Question was only temporarily resolved in 1870 by the incorporation of the Province of Manitoba, which established a dual system of Protestant and Roman Catholic education. Anglo-Protestant settlement in the 1870s and 1880s, largely from Ontario, irrevocably tipped the balance of power: it was not long before public funding for Catholic schools, including St. Mary’s, was abolished and in 1890 the French language lost its official language status.12 When the First World War broke out, the tensions expressed in the debates over schools were further intensified, and even Wilfred Laurier’s remedial legislation allowing multilingual teaching was repealed. By 1916 the English-speaking majority in the province had succeeded in its program to enforce the assimilation of minorities, including the French, when it declared "that English must henceforth be the only language of instruction" (Berger 76).

9 Notably, St. Mary’s Academy was established in 1869 by the French to address the split between the French-Catholic community on the St.Boniface side of the river and the growing English-Catholic community downtown. As controversial as it might have been, its purpose was to install a Catholic presence in the nascent city of Winnipeg, which had just granted parcels of land in its centre to Presbyterians, Anglicans, and Methodists. This was tempered, however, by Bishop Taché’s choice of Father McCarthy as the first Chaplin of St. Mary’s, which signaled to Catholics on the west side of the Red River that it would serve an English-speaking population (Rostecki and Ritchie 7-8).13 Seven years later, when the Quebec nursing order of Grey Nuns appropriately passed the Academy on to the teaching order of the Holy Names, the French identity and roots of the Academy were retained. While St. Mary’s fully lived up to Taché’s mandate of educating Catholic students in English, becoming, in effect, a British-identified Catholic institution, the order which ran it, and its formal administration, remained French (Rostecki and Ritchie 51).14 In all likelihood, it was for this reason that St. Mary’s, which published Sister Agnes’s plays, as well as the Order of the Holy Names, which condoned them, tolerated her openly anti-British stance, even as she was living and serving in British Canada.

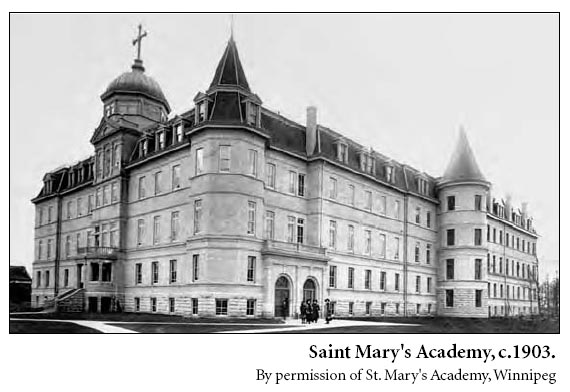

Saint Mary's Academy, c.1903.

Display large image of Figure 1

10 In important respects, St. Mary’s also nurtured Sister Agnes’s autonomy, simply because it placed her among the privileged. St. Mary’s was located on fourteen acres of dense forest in the Western Fort Rouge. It had long been an elite institution that served Winnipeg’s upper- and middle-class English population: it was the proper setting in which to cultivate religiosity, gentility, solitude, and sophistication (38).15 When most of Winnipeg’s dwellings were poor and their sanitation bad, its palatial structure rose out of the clearing like a European castle with a courtyard, turrets, porticos and pillars; it had a telephone, electric lights, running water, and rooms for every activity, including a"complete little theatre."16 St. Mary’s did educate some poor girls: there was a bursary program. There were also some non-Catholics and some French girls. Largely, however, its population was drawn from Winnipeg’s elite "young ladies" and Catholic, middle-class Anglo-Canadian girls of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Northwestern Ontario, and the Northern States.17

11 The convent, which was housed in the school, was not simply a female environment, it was one which inspired a feminist sensibility and women’s agency, even if this is not the language the nuns themselves would have used. Its cenobicial life, while not "enclosed," created unique opportunities for women’s independence through its separation of women from men and the secular sphere. While it required many acts of submission, like "sacrifice and mortification," a "regime of prayer and work," and the "subjugation of the will to the authority of the mother superior," it still afforded women like Sister Mary Agnes enclaves of freedom in which they, more than women in the secular world, enjoyed great intellectual and professional latitude (Danylewycz 84-85).18 Within the convent, choir sisters like Sister Agnes "bargained for and protected their own economic rights [...]staffed [their] own schools and opened the door to education and occupational advancement"; they "acquired virtual autonomy in the areas of the certification and the administration of their schools" and played a central role in education (95).19

12 Sister Agnes, for example, was prima inter pares and among the most successful members of her order, in which she held high-ranking positions beginning in 1894. At the height of her career, she was Local Assistant to the Superior, Provincial Director of English Studies and Third Provincial Councillor: she held all of these positions for most of her tenure at St. Mary’s. She taught there almost exclusively at the university level ("Obituary").20 Her main fields of scholarly qualification were English and Latin, which she taught from 1911 until her final year. She taught university courses in philosophy, logic, and rhetoric.21 Her dedication was lauded by her peers. According to her obituary, at Holy Names, "teaching had [its] highest exponent" in her "love of piety, attentiveness to the work in hand, respect, moderation, deference, punctuality, a constant cheerfulness, a sane and judicious valuation of ordinary happenings’ [… and] humility which she possessed in a very marked degree" ("Obituary").22 Sister Agnes’s diverse experience as both a professorial administrator and teacher would have made her accustomed to exercising power and an independence of mind which was not usually within the purview of female experience at this time.23

13 There is no direct connection between the Academy and the feminist activism of the age, and, in fact, a significant tradition of Protestant middle-class feminist reform was anti-Catholic (Ruether). Yet St. Mary’s was a leader in women’s education in Winnipeg, which suggests that the nuns who chartered its course also held progressive views. The Academy was in daily receipt of the Manitoba Free Press and its faculty would have been very familiar with the names and writing of Nelly McClung, Lillian Beynon Thomas, E. Cora Hind, and Dr. Amelia Yeomans. Its teachers would have been well aware of women’s political battles for access to the professions, decent wages, suffrage, divorce, child custody, property rights: all part of the unflagging energy of Manitoba’s suffrage movement, the first in the country to be victorious. Given their own women-centred, women-run world, its teachers, must have identified with some of the values and aims of the movement, even if they were not members and did not participate in provincial politics. St.Mary’s was fundamental in helping realize the right of women to post-secondary education, which was an on-going demand of women’s rights activists and women reformers. While it always provided a program in the feminine arts of painting, music, and needle-work, in Sister Agnes’s time it offered Normal School equivalency courses, commercial courses, and an academic curriculum that prepared students for university studies.24 In 1913, St. Mary’s allied institute, St. Mary’s College, began teaching young women who then received their Bachelor of Arts degrees from the University of Manitoba.25 The advanced goals for which St. Mary’s prepared its female students are indicative of it as an institution that provided a progressive milieu for women, and Sister Agnes, as a university teacher, was an important part of fashioning that milieu during the nineteen years she spent there.

14 Sister Agnes was a prodigious writer who made her largest contribution to inculcating progressive views in young women through mounting, publishing, and disseminating her plays.26 Her first to appear in the St. Mary’s daily "Chronicles" was The Arch of Success, staged as part of the summer graduation ceremony in June 1912. Over subsequent years, her plays were often incorporated into St. Mary’s graduation and awards ceremonies.27 Less frequently, she put them on to raise money for Academy projects, both philanthropic and aesthetic ("Chroniques" 157).28 Marie-Magdalene was performed in 1921 by grade eleven and twelve students to"help poor children in Europe.29 A Day With Peggy was staged in 1928"not only to give pleasure but also to give the school a compensation for all the expenses needed to prepare for their graduation" (278).30 "With the proceeds of the sale of her Dialogues in 1921, she bought two beautiful statues representing two angels, standing in contemplation, which were proudly displayed on a pedestal near the main altar" (165).

15 Sister Agnes undertook to have her writing legitimated and recognized by her order as part of her Christian work. She submitted twelve plays for consideration to the Mother Superior when she applied for permission to publish them in 1913. On 15 December she gained that permission and the formal acknowledgement that her dramas and the dialogues were written "for the benefit of our English sisters preparing receptions and the festivals."31 In 1914 she had her play preparation recognized as part of her obediences.32 The degree to which she administered her literary career and determined the conditions under which she allowed her plays to be used and distributed further illustrates the unusual autonomy she had as a nun and contributed to her success as a woman playwright at the time.33 While she sought formal permission to advertise her plays in 1925, she was doing so as early as 1923 in the trade magazine Catholic School Journal.34 The advertisements must have been effective because her "Obituary" claims that "scarcely a day passed without bringing her an order to fill."35 Sister Agnes "received daily orders for her plays from many different Sisterhoods and from far and wide—England, Philippine Islands, British Columbia, New Brunswick, and from colleges and Academies of almost every State in the US [...]. Letters of praise that are received after the play has been a dramatic success show us how highly Sister’s beautiful plays are valued" ("Généalogie").32

16 The plays of Sister Agnes are so numerous that only a monograph dedicated to their analysis could do them justice: she left more than 70 titles of plays and recitations, several in collections, and many single volume works, virtually all of them published under St. Mary’s own imprint.37 Largely, although not exclusively, they are plays for school-aged girls. They cover a substantial range of comedic genres including mission plays, biblical and historical plays, allegories, plays for occasions like graduation and Christmas, Irish plays, and boarding-school plays. Generally speaking, they are Christian comedies that focus on white, middle-class, female characters who embody the ethic of active Catholicism that infused Agnes’s own life. They teach the value of women’s initiative, strength, and independent spirit on the one hand and self-sacrifice, devotion, and charity on the other. At times they are supportive of both the domestic and liberal feminist politics of their age.

17 "A Patriot’s Daughter," written on the eve of the First World War, is a protest play, inspired, no doubt, by Sister Agnes’s identification with Irish, American, and French views as they clashed with her location in a British Canadian context. Its women characters are the agents of dissent and are motivated by her feminist sensibility.

18 At a time when English Canadians who ran Winnipeg identified their own interests and those of the country with the Empire and when flag-waving and military recruitment were at a peak, "A Patriot’s Daughter" was vehemently anti-British and pro-American. It displaces its critique of World War I onto the American War of Independence when relations between the two countries were at their worst. It re-imagines this history, war, and politics from a feminine and female point of view. It takes as one of its major motifs women and war and in the end asserts a liberal feminist politic that is grounded in democracy and Christianity. Its strong and audacious judgment against the British in a previous historical moment conveys the degree to which Sister Agnes must have experienced herself as both separate from the political climate of Winnipeg and liberated to speak in opposition to it, even as her order served the children of largely British-identified Canadian families.

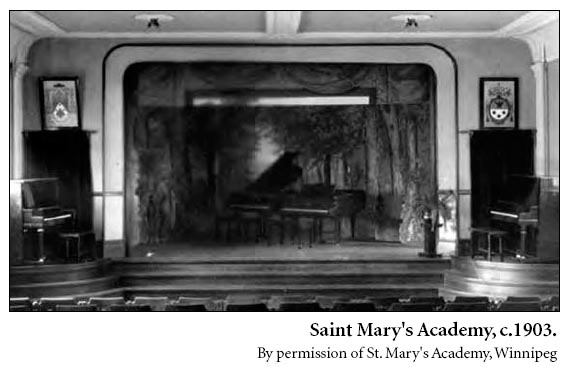

Saint Mary's Academy, c.1903.

Display large image of Figure 2

19 A short, three-act drawing-room comedy for young women, "A Patriot’s Daughter" opens on a street in Boston in "1774, the year after the ‘Boston Tea-Party’ and before the battle of Lexington." Betty Heywood, a Boston patriot and the hero of the play, is taking leave of her mother who, reticently, brought her to visit her ailing friend Rachel Winslow, the daughter of Tory Loyalists. Betty has knowledge of her father’s activities as captain of a company of "minute men" and, despite promises of "prudence and discretion," Mrs. Heywood fears that Betty "is too impetuous, and will [...]bring us all to trouble" (116). Her mother’s apprehension is warranted. But, just as Betty emphatically dedicates her fidelity to the Yankees, the evil Arabella Preston, a spy for the loyalist cause, crosses the stage, secrets herself in the bushes, and overhears most of the conversation. The Winslows’ house, Mrs. Heywood has heard, "is damp and unwholesome because of the winds that blow [...]from Neponset swamps and bring a kind of malarial fever" (117). As a final gesture she arms her daughter with magic powder from the Indians, which she says is "a quick and certain cure for such attacks" (117).

20 Act II takes place in an elegantly furnished apartment in Mrs. Winslow’s house. Rachel’s wicked step-mother is hosting an afternoon tea party for the wife of the Governor of Massachusetts, British General Gage, who is honouring the family with an extended stay. Offended by the decadence and ostentation of the British ladies, Betty and her rebel friend Rachel stage a Boston Tea Party à la femme. Saucily costumed as Puritan maids, they dump salt into the ladies’ tea and serve it to a chorus of styptic grimaces. Betty is interrogated by the General’s wife who has been informed of her intimacy with her father’s activities by Arabella. But the extent to which the girls’ rebelliousness is punished is only clear in the final act, which imagines that one month has passed in which Mrs. Gage has kept Betty under arrest, as well as imprisoned Betty’s father. The anagnorisis or discovery that resolves the plot occurs when Mrs. Gage takes ill and Betty, motivated by a higher sense of Christian duty, sends her the magic Indian powder given to her by her mother. Mrs. Gage is instantly revived and so grateful to Betty for saving her life that she sets her and her father free.

21 Set against the back-drop of the American Revolution, a major theme of "A Patriot’s Daughter" is its anti-British sentiment, which is rooted in its critique of British political and economic policies in colonial America. It was very likely published before Woodrow Wilson’s August 1914 "Declaration of Neutrality," and, like the declaration, it is a response to the great ethnic opposition, in particular Irish opposition, in the United States to assisting Britain at the onset of World War I. The play, therefore, is anything but neutral. It relocates a stinging critique of the British in the present onto a cluster of events around the American War of Independence and sets them in Boston, Sister Agnes’s birthplace and the heartland of rebel activity. It occurs at a pivotal moment, the year before the war’s first official battle. But the conflict has already begun: "Have you forgotten the ‘Boston Massacre’ four years ago, and the killing of simple schoolboys by the British soldiers?" Mrs. Heywood asks her daughter (116). The edges of the play are haunted by General Gage, Governor of Massachusetts, and Parliament has enacted the "Coercive Acts" which galvanize the resistance.38 Minute Men, like Betty’s father, are mustering troops. The play represents the single most acrimonious period in the history of American/Anglo relations from the American point of view. In it, the British are brutal "lobster-backs," class-bound overlords who take the"severest measures"to suppress and punish "the common people"; they "look upon the Colonists as their slaves," Betty tells us, "fit only to labor for them, and to be punished with the lash or bayonet if they rebel under such treatment and assert their rights" (119). It is a play whose opposition to the British is so emphatic that it can only be read as a counter to the intensity of British patriotism that captivated Winnipeg and most other cities in English Canada at the time it was written.

22 The same anti-British sentiments infuse Rachel’s extra-diegetic ‘story’ of her mother’s death, except here the play lays bear the deep wounds of French animosity toward the British in Canada. Rachel is just a small child when a British soldier"returning from the capture of Quebec" stopped at her home and"forced" her "mother to leave her sick-bed to prepare him a supper and a night’s lodging." She leads us to believe that her already ailing mother dies of the exertion. The scar it leaves on the little girl is indelible and she has "hated the ‘Red-Coats’ ever since" (119). The story may seem an inappreciable detail in the larger drama, but its function is significant: it makes a narrative link between the British Conquest of New France, the defining moment in the perpetual domination of the French Catholics by the British Protestants in Canada, and British repression of the Thirteen Colonies during the Seven Years War, which was one of the causes of the American War of Independence. In effect, it is a kind of object lesson Sister Agnes directs at the audience: it aims to remind them that the leaders to whom most Canadians give their unbridled support in the present were enemies, to the French as well as to the Americans, in the past.

23 At the opening of Act I, Betty says to her mother, "surely, the British general did not come here to make war on girls?"(116). Her lament introduces not only the play’s anti-British theme but its feminist values, because it is about a girl’s war. Almost the first thing Betty says is, "I wish I were a man, that I might fight for the cause of justice and liberty and help to overthrow the reign of tyranny in these fair colonies" (115). Notably, women’s roles in war is a recurring motif in women’s drama of the period, particularly the longing to fight in battle.39 When Betty pronounces it a "pity you are only a woman, and can’t wield a sword in the cause of liberty," Rachel insists that "women can help the good cause in other ways—and they do" (120). In effect, the girls are rebel soldiers behind enemy lines. The drawing-room is their battlefield, the dress of Puritan maids is their armour, and tea is their weapon. Like the women of the age she represents, who took a leadership role in the fight against taxation by causing a general boycott of tea in 1773, Betty has not "seen tea at home since the ‘Boston Tea-Party’ last year, and [… hasn’t] tasted any since we all signed the agreement four years ago" (120; Jansen n.p.).40

24 For the "Tory Ladies" who make it a point to drink tea continually and give afternoon tea-parties to show their loyalty to the British, the drawing room is also their war room (120). They are comprised of a group of non-speaking clowns that Rachel calls "painted, powdered women," and "stiff dames with their stupid talk and endless airs," who drink salted tea and gossip about it behind the back of the hostess and her honored guest (122). But first among them are Mrs. Winslow and Mrs. Gage, the alazons, or imposters in control of the comic society as the play unfolds, whose unbridled superiority is a delightful parody of British manners and "off with their heads" royalist politics. As we first meet her, Mrs.Winslow pronounces, "I agree with you, Madam, — pray take some cream with your tea, —that the king’s officers are justified in taking the severest measures to suppress these treasonable insurrections" (124). Mrs. Gage is only slightly more absolutist in her declarations of supreme authority: "Nothing else will bring these vulgar agitators to their senses. The common people never know what is for their good, and must be forced into submission to the royal will" (124). As the Royalist women continue to talk about the insurgency, they reveal the relationship between the paternalism that governs them in politics and the materialism and sexism that governs their lives. The rebel agitation, it seems, threatens their sense of decorum and impedes the easy execution of the feminine pursuits as they are dictated by London. Mrs. Barrett is "really vexatious" that "peaceful relations with the mother-country" have interrupted the flow of new novels and new gowns, keeping her "entirely behind the London fashions" (125). Mrs. Winslow laments knowing nothing of the "court news till London circles have quite ceased talking about it"(125). Mrs.Gage fears she will"soon be reduced to talking of the crops and products of the spinning-wheel like our good neighbors the farmers’ wives" (125). In the context of a play that promotes women’s independence and agency, it is significant that what Mrs. Gage finds most contemptible is the willingness of the Patriot women to fight alongside the men as wives who, she says derisively "laughing," "are ready to take up arms with their fathers and husbands to force the king’s ministers to remove the tax on tea!" (125).

25 Betty as the rebel-hero and her co-agitator Rachel embody the values that the play holds sacred: their actions are underpinned by a politics of equality feminism that is grounded in American political values as they are expressed in the Declaration of Independence (136). Rachel says, "We will assert our rights [...]and gain them, too, in spite of the king and his lobsters!" (119-20). Betty is as loyal and brave as any male soldier and, like a male solider, motivated by "liberty and justice" for a people who have no right to representation and live under a government that continually abuses its citizenry (136). The risks she takes and the information for which she is responsible are also equal in gravity: she knows the "plans of the patriots, their names, their numbers." Arabella has already made it clear she intends to inform General Gage and her brother of this. If Betty divulges what she knows, her father could be "hanged as a traitor"(116). The real test of her heroic metal, therefore, is her ability to keep a secret. During the interrogation scene she plays faux-naïf to Mrs. Gage’s examiner, quick-wittedly misinterpreting her questions and frustrating the lady’s attempts to educe information and all the while ironically undermining her power and position. When Mrs. Gage asks if her father "was lately made captain of a company of militia, and [...]trains his men every day to the use of arms," Betty responds, "I know that Father has trained my little brother Ben to use his arms in climbing" (127-28). When asked about her father’s "future plans" Betty speaks of the "splendid crop of apples next year," and when Mrs. Gage demands to know "about the stores now being collected at Concord," Betty enumerates the merchants in town (129). In this girl’s war, words are also weapons and of great consequence. Betty says, "I would have my tongue pulled out before I’d let it play traitor to our cause";"all the bayonets of the British soldiers could not force from me a word that would be of use to them"she tells her mother (115, 117). She is as good as her word: her actions are intelligent, brave and as trustworthy as "the best men of the colonies" (131). Even after a month under house arrest, she does not break down: "if they threaten me with death itself! "she insists, "I will [be] true to the cause of liberty and justice" (136).

26 These core American values, which also function as feminist values in the mouth and through the actions of these rebellious female characters, are closely linked to Betty and Rachel’s sense of the greater Christian good, particularly Christ’s teaching, "to love thy neighbour as thyself." In the same conversation in which Rachel tells her step-mother she does "not recognize [the King’s] authority" and that she has "no respect for tyrants," she also learns that Mrs. Gage is "seriously ill" (133). Despite being continually harangued by her step-mother for her rebel behaviour during Mrs. Gage’s sojourn, Rachel is immediately struck by a higher duty: "as long as Mrs. Gage is ill and suffering, she has a claim on our charity, and I shall be happy to do anything in my power to increase her comfort" (134). Betty, imprisoned in the parlour, responds in kind:"poor lady! If I could think of anything to relieve or comfort her, I would really do it"(134). Like the Good Samaritan who gives of himself to mitigate the suffering of the dying man, Betty sends the magic powder to "comfort her." When her mother tells her it "was an act of charity and [that] God will reward you," she names one of the greatest virtues in all of Catholicism, one which motivated the founding of many religious orders of women—the willingness to sacrifice one’s self for the good of another in order to glorify God and attain salvation (134, 137).

27 Christianity even makes Mrs. Winslow’s servant Dinah a patriot to the Loyalist cause. Although she does not achieve a position of social equality because of her race, the qualities of Christian simplicity and modesty do elevate her character to one of moral equality. Certainly, Dinah is constructed through a racist ideology as a comic"darkie," but her character is not solely dumb and naïve, because she also possesses an abhorrence of artifice and social pretense. "I jes’ dunno why dese ‘ere Britisher ladies do tink such an awful sight of drinking tea [...]. An’ den to see de amount of paint an’ patch dey put on dair faces! [...] Why, nouw, can’t dey leave dair skin de way de good Lord make it? He know a heap more’n dey do" (121). Christianity, therefore, is the great human leveler. Within the embrace of its value system, characters that are wildly different in social stature and political stripes, are made good and moral. Dinah becomes wise; Mrs. Gage, humble; and Betty and Rachel, charitable.

28 The critical content of "A Patriot’s Daughter" is evidence that Sister Agnes enjoyed a unique position of freedom as a woman to express her political opinions, on the page and on the stage. It clearly reflects her profound disassociation from her host country, a deep-seated alienation that, along with her feminist sensibility, furthered her inclination to be a politically provocative playwright. While the anti-British flavour of "A Patriot’s Daughter" does not re-emerge with the same bald intensity in The Red Cross Helpers, a jingoistic patriotism, as well as the spirit of equality for women, is at the core of its plot and its political convictions.

29 The Red Cross Helpers was published at the end of the World War I, but it was written, no doubt, around the time the US joined the fight in April of 1917. Its support of the war reflects this change in the US position, as well as that of Quebec, where Henri Bourassa had also conceded Canada’s limited involvement. Its stage directions recognize the possibility of its being performed in a British context—it was certainly written in one—but its radically American politics prevent an understanding of these stage directions as anything more than a polite tip of the hat to this context, a well-mannered but empty gesture. Like "A Patriot’s Daughter," it enacts war from within a woman’s world. It makes a connection between patriotism and an expanded social role for women, but does not extend its progressive views to the Chinese character who, although a man, is emasculated as a result of being Asian. It is both a melodrama and a reworking of the biblical parable of the "Widow’s Mite" and in each story it is a woman hero in whom the Christian value of Charity and the American values of "freedom," "liberty" and property are wed.

30 The Red Cross Helpers is a two-act comedy, partly of the drawing-room type, but mostly melodrama in its characterization, situation, and dialogue. Written for a large number of school-girls, it opens in a room in "Hudsonville Academy." A group of patriotic graduates, volunteering for the Red Cross, are knitting socks and scarves for the troops overseas when the Principal, Miss Holmes, brings news that she and the school trustees have "formally offered the building and grounds to the government" for use as a "military hospital" (5).41 Now the last graduates of the Academy, the girls decide to abandon the "elaborate Commencement Exercises" they had planned and put their time and money into a concert to raise funds for a hospital ward. In a busy Act, Mabel collects money, poor but virtuous Elsie donates her pearl ring, and Marie, the Belgian refugee, is persuaded to make a spectacle with her tragic war story at the upcoming concert. Frances, a.k.a.Captain Frank, a Girl Scout and the miles gloriosus of the piece, has "enlisted for home defense" and marches back and forth across the stage, commanding the troops, especially the Chinese Laundry Boy, Li Chang. The girls’ united front is threatened by the German-born Hilda who refuses to "give one penny to help the enemies of [her] country" (8). But Hilda is only a foil for the real devil-in-paradise, the music teacher Fraulein Schmidt, who closes the Act by stealing the purse containing the girls’ money and divulging her plan to foil the concert by drugging Marie, its star performer and the most vulnerable of the students.

31 Act II takes place in the school grounds under the flag-pole. The girls are discussing the evening’s entertainment when Mabel enters with the news that the money has gone missing and both Hilda and the "half-German" Elsie are suspected of stealing it. They strategize how to recover the money and Frank turns to interrogating Li Chang, when Marie is overpowered with drowsiness and falls unconscious. The climax of the play, the evil coup de grâce, occurs in a fast closing scene in which Miss Schmidt sneaks onto the schoolyard to admire the effects of her evil handiwork, but is so overcome with the sight of the American flag that, in a sudden paroxysm of rage, she attempts to tear it down. Elsie, who has been watching from the sidelines, intervenes, grabbing Miss Schmidt’s arm just in time to prevent her from doing so. Then all of the characters rush in, including the Principal and a detective, who expose Miss Schmidt as a spy and thief for the German side.

32 The Red Cross Helpers is confrontational because it is set in the US, is overtly American in its patriotism, and provides a state-side view of the war in a Canadian city, which, as I have said, was permeated by a fear of Americans and the influence of their increasing numbers in the West. Yet it stands alone among Sister Agnes’s extant plays in that its stage directions specifically imagine the possibility of a British production and a British audience. "If this play is given in a British colony it can easily be adapted to changed conditions, by substituting British patriotic songs for American; the word ‘king’ for ‘president’; the British flag for the American; etc" (3). In effect, as aggressive as the play is, its directions appear to recognize the inappropriateness of its bald American patriotism in a British context, something "A Patriot’s Daughter," in its deliberately oppositional stance, certainly does not do. Nonetheless, the solution it offers is simply to substitute American songs, symbols, and sentiments with British ones, as if this could possibly mask the ideological investments of the play. While the directions make an overture to the British and her "colonies," the American attitudes which drive the plot make it near impossible to enact these directions in a satisfactory rendition of the play and therefore to take them at all seriously. In fact, the directions can be read as a slight against Canada and its nationhood. The reference to a "British colony" seems to imply Canada, as Canada was the play’s place of publication and a most likely British context for its staging. But what it flagrantly fails to recognize is that Canada is a country, not a colony, and had been so for over half a century.

33 The melodrama of The Red Cross Helpers mirrors the action of the war from the point of view of the United States: free and innocent Americans are the victims of an unprovoked attack by the ruthless Germans, while Belgium is an innocent casualty. Its mood is polarized between American virtue and German evil embodied by stock characters in a plot that involves upstanding American students raising money for the war effort, a spying German teacher who steals it, and the innocent Belgian girl who is abused in the process. It ends with a ritual "driving out" when all of the characters, who represent a cross-section of American society, including its officials, fill the stage, and Miss Schmidt is arrested and led away by the detective (24; Frye 45). The expulsion of the pharmakos gives itself over to an adulation of Elsie whose acts of bravery and Christian charity have defended the country, the flag, and its people. Its overall tone is generally one of patriotic passion and celebration, and its exuberant nationalism expresses the mood of a country newly engaged in a war campaign. While Act I closes with a song, entitled "America, My Homeland," the play is infused with the jingoistic naiveté of the much more popular US hit, "Over There"(1917), an expression that is repeated more than once in the play. Its second act, dominated by the flagpole, includes a flag drill, and ends with the Star-Spangled Banner. It is a melodrama that, in its move from dissolution to salvation, idealizes the patriotic and Christian views assumed to be held by the audience. It expresses the optimism of the age, and here that optimism resides in the democratic ideal of women’s equal participation in the social world and equal responsibility for the security of the state.

34 Patriotism, as a value, is a central motif in The Red Cross Helpers. In a certain way, the whole point of the play is to test the patriotic allegiances to America of characters who have foreign affiliations. German-born Hilda has no loyalty to the United States:"I hope that the German arms will triumph everywhere, and that all the nations of the earth will be subjected to the rule of our great Kaiser. Then will ‘kultur’ prevail and all the blessings which follow when Prussian ideals are spread"(9). The play distinguishes between Hilda and Elsie, her American-born half sister, whose love and dedication to America are as strongly felt as Hilda’s contempt for it. Although Helen is appalled by Hilda’s German patriotism, calling her a "villain" and a "traitor," Mabel recognizes in her a respect for home and family: be"just; remember that Hilda’s father and mother were both Germans, and she herself was born in Germany" (9).

35 This same kind of respect is not extended to the character of Li Chang who does not understand the concept of loyalty and is perfectly willing to side with either the Germans or the Americans to save his own skin. Like Dinah in "A Patriot’s Daughter," Li provides the play with its ideologically racist comedy. His character conforms to familiar pejorative stereotypes that adhered to the Chinese both in Canada and the United States during the period: he is effeminate, powerless, uneducated, cowardly, and works in a laundry. Indeed, his lack of patriotism appears to invoke one of the most pervasive stereotypes of all:"that of the unassimilable Asian" (Williams 97; Ward 12).42 Loyalty, patriotism and the value of independence are entirely foreign to him, making him significantly more contemptible, if less dangerous, than the enemy. When Hilda demands that he "beg my pardon for slandering my nation," Li falls to his knees pleading I’ll"say what you tell me"(13). When she asks him to "swear you will never speak ill of the Germans or the Kaiser" he thinks she wants to hear him use profanity: "Me know only one swear word, —damn; you wish me say dat for the Kaiser?" (13). Frank demands the same show of submission: "Say ‘Captain’ or I’ll have you punished for disrespect to authority" (13). When Frank threatens to shoot him for being a "German spy" and a "vile traitor," he begs her not to, pleading "O don’t, please, Mees Cap’n! China boy do anything, say anything you wish" (13). While Hilda is the enemy she is still European and shares similar patriotic values with the girls of Hudsonville Academy, even if the object of her patriotism is different; her half-sister is evidence that over time, the allegiances of Europeans who come to America can and do change. Li Chang falls into a different category, however, as he is too dumb to know real Christian virtue, too cowardly to embrace patriotism, and too emasculated to wear a uniform. The single value that motivates his fidelity is money: for those who can put money in his purse he will do and say anything.

36 The representation of the girls in the play as Red Cross helpers makes a direct connection between patriotism and an expanding politics of domestic feminism during the first age of women’s organizations.43 Although they appear the epitome of conventional middle-class femininity in the sewing circle that opens the play, Mabel, Lillian and Ida are making clothes for the Junior Red Cross which interpolated young women as naturally maternal and appealed to them to employ their domestic skills in the service of the war relief effort. They are the picture of young mothers-in-training, the very image the Red Cross wanted to portray in its famous World War I poster of "the greatest mother in the world," part of their campaign to inspire eleven million new members in eighteen months (American Red Cross). Like their real world counterparts the girls of Hudsonville Academy are participating in the war effort by conducting a patriotic drive, providing relief articles for the boys"over there" and tending to the sick at home.44

37 The Girl Scouts are represented by Frank in the play, and, while she also has a patriotic function, her expanded woman’s role receives nothing like the reverent treatment enjoyed by the Red Cross. Frank is a pre-pubescent miles gloriosus whose main function, like Li Chang, across from whom she plays, is to delight the audience with her caricature of gender. "Dressed in khaki, short skirt, military jacket and boots," she parades across the stage demanding to be called "Captain." She is unrecognized by Gertrude who asks "when did you enlist in Uncle Sam’s Army," because the Girl Scouts were a new organization, having been founded in the United States in 1910.45 A character that seems to poke fun at the first Scout publication, How Girls Can Help Their Country (1913), Frank understands "home defense" not as the production and conservation of food, the sale of war bonds, and work in hospitals, which Girl Scouts actually participated in, but bestowing citizenship, performing interrogations, and converting foreigners to American ideals (14). Frank calls herself a "vigilant sentinel," but we recognize her as a type of braggart soldier who, with her uniform and pistol, charges through the play threatening to have the girls "arrested for lèse-majesté" and promising that "William the Second shall be William the last" (12). Despite the Scout’s focus upon "housewifery," Frank’s masculine, military persona critiques the Scouts’ expanded sphere of women’s influence into quasi military activities (Revzin).

38 Feminism and patriotism are also conjoined with Christianity in this play through its adaptation of the biblical parable of the "Widow’s Offering." As the parable is recalled in the gospels of Mark and Luke, Jesus is sitting near the temple treasury, watching many wealthy people make large offerings. To the surprise of his disciples, Jesus is most impressed with the offering of the poor widow, which is the smallest of all:"Verily I say unto you, this poor widow cast in more than all they that are casting into the treasury: for they all did cast in of their superfluity; but she of her want did cast in all that she had, even all her living" (Mark 12:41-44).46 The parable functions in an analogous fashion in the dramatic structure of the play. The "rich [who] cast in much" are represented by the chorus of girl graduates: they are of substantial means and know they are in a position to make a "handsome" donation to the hospital (6). The first act is dedicated to their collection of money and the decision to give up what Mabel calls their "vanities"— items such as "fine feathers," "graduation dresses, gloves [and] flowers"—in order to augment the country’s military coffers (6). Elsie is the poor believer, modeled on the widow: she has no money of her own, but nevertheless donates the most valuable gift of all, her pearl ring, hoping that it"will be acceptable in the sight of Heaven, even as was the ‘widow’s mite’" (8). She even takes on extra work that yields twenty dollars to increase her already generous contribution (25).

39 While the original biblical parable focuses only upon Christian self-sacrifice, in The Red Cross Helpers this parable is adapted to the play’s patriotic cause and is further endowed with a political and feminist dimension. In it, Elsie makes explicit that her monetary donation is a Christian offering; just as importantly, however, it is also a contribution to the ideological aims of the state. "Nothing," she says, "is dearer to my heart than the cause for which my countrymen are fighting, —to secure to America and the whole world, the blessings of freedom, righteousness, and civilization" (8). Apart from the adaptation of the parable for patriotic ends, the "widow’s mite" can also be understood to reflect a ‘woman’s might.’ This is because it represents not only what women give, but also how they act and what they do in the political domain. Indeed, this is the play’s feminist dimension. It is a story of a woman who through her sacrifices for God and the State enacts her political will. She makes a choice that she is going to support the United States government when Hilda tries to talk her out of it, and by so doing tells us that women can and should act politically. In the parable, "mite"becomes might when Elsie’s sacrifice shifts from the monetary to the corporeal in the struggle over the flag: "Either your blood or mine shall be shed before you touch with your traitor hands the sacred emblem of our glorious country" (23). In the marriage of Christianity, patriotism, and feminism, Elsie represents women as active, independent political agents and moves the message of the play beyond domestic feminism to a form of equity feminism in which women as well as men are responsible for the defense of the country.

40 The unabashed American patriotism of the Red Cross Helpers, like "A Patriot’s Daughter," points to Sister Agnes’s experience as an outsider while living in Canada. It also suggests she was confident in her right as a woman to engage in social and political critique, something that was typically the purview of Protestant women reformers and men. While it is not vehemently anti-British, its American patriotism is still a plucky and spirited rebuke of the country which fostered her pedagogical and literary career. Even if its male-identified character "Frank" expresses a critique of women in a quasi-military role, it is nevertheless a celebration of women’s expanded domestic duties and the application of these to the rough and tumble world of war.

41 One does not commonly think of the cloister as a place which fosters ideas of social and political rebellion. Neither does one necessarily think of turn-of-the-twentieth-century young girls’ dramas as a forum for feminist thought. Yet, as this brief study of Sister Agnes’s life and work reveals, the Order of the Holy Names and others like it one hundred years ago were enclaves of female power. Despite the Church hierarchy and the authority of priests, women in Catholic convents, especially those who were educated, had significant control over the conditions of their own lives, enjoyed professional opportunities and freedom of thought. As an Irish-American, an identity that was dually formed out of a Irish and American resistance against Britain, Sister Agnes was an outsider in Canada, one whose French Catholic order also set her apart and provided her a sanctuary within which to safely voice her politically controversial views, including her anti-British and feminist views. The plays examined here are evidence of this: they articulate opinions that challenge the political majority in Canada, advocate American political values, and create characters that express both equity and domestic feminism. However, the force with which the play’s politics are articulated is best explained by Sister Agnes’s location in Winnipeg, a place which was both a progressive province for women on the one hand and "furiously British" on the other.47

Works Cited

Agnes, Sister Mary. "Biographical File." Archives. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy.

American Red Cross. "Museum: Explore Our History: A Brief History of the American Red Cross"and"The American Red Cross Experiences Growing Pains and Reorganization." 18 April 2006 http://www.redcross.org/museum/history/leaders.asp.

Armstrong, Karen. The End of Silence: Women and the Priesthood. London: Fourth Estate, 1993.

Batte, Helen (Sister John Thomas). Rooted in Hope. A History of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary of the Ontario Province. Windsor, Ont. : Windsor Print and Litho, 1983.

Beauchamp, Helen. "Scrapbook." Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy.

Berger, Thomas R. Fragile Freedoms: Human Rights and Dissent in Canada. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1982.

"Bibliographical Note on Sister Mary Agnes by Julie Marie." Archives. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy.

Brock Bibliography of Published Canadian Plays in English, 1766-1978. Ed. Anton Wagner. Toronto: Playwrights, 1980.

Browne, Jefferson B. "Key West: The Old and the New"(1912): Floripedia: A Florida Encyclopedia, "Key West: Key West Education." 2005. 22 January 2006 http://fcit.usf.edu/florida/docs/k/keys04.htm.

Butterill, Chris Keegan. The Early History of St. Mary’s Academy. Winnipeg: University of Winnipeg, St. Paul’s College, 1983.

Carter-Broun, Louise. "A Solider." A Playlet in One Act. [Typescript. US copyright registered by author, Toronto 1913. Mount Saint Vincent].

Catholic Encyclopedia. "Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary." 2006. 27 January 2006 http://www.newadvent.org/cathen.

Catholic School Journal. "Plays for Catholic Schools." November 1923: 284, November 1927: 281, December 1927:329, April 1928: 37 May 1929: 93, June 1929: 143.

Chaput, Hélène. Synopsis S. N. J. M. , 1874-1984 : une histoire sommaire des Soeurs S. N. J. M. au Manitoba / a syllabus of S. N. J. M. history in Manitoba. Saint-Boniface, Manitoba: Académie Saint-Joseph, c1985.

Cook, Ramsay. "The Triumph and Trials of Materialism 1900-1945." The Illustrated History of Canada. Ed. Craig Brown. Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1987. 377- 466.

"Chroniques 1909-1936." Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary of Manitoba Fonds. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Archives of the Saint-Boniface Historical Society/La Société historique de Saint-Boniface.

Curzon, Sarah Anne. Laura Secord, The Heroine of 1812: A Drama and Other Poems. Toronto: Blackett Robinson, 1887.

Danylewycz, Marta. Taking the Veil: An Alternative to Marriage, Motherhood, and Spinsterhood in Quebec, 1840-1920. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1987.

Davis, Richard Harding. "The Burning of Louvain." New York Tribune 31 August 1914. 1 February 1996. 18 April 2006 http://www.lib.byu.edu/~rdh/wwi/1914/louvburn.html.

Dooley, Chris. "E. Cora Hind," "Francis Marion Beynon," "Lillian Beynon Thomas," "Political Equality League." TimeLinks: the historical web site about Manitoba in the decade from 1910 to 1920. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba. 1997. 18 May 2006 http://timelinks.merlin.mb.ca.

Ebaugh, Helen Rose Fuchs. Women in the Vanishing Cloister: Organizational Decline in Catholic Religious Orders in the United States. New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 1993.

Fay, Terence J. A History of Canadian Catholics: Gallicanism, Romanism, and Canadianism. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2002.

Fischlin, Daniel. "Adaptation as Rite of Passage." Canadian Theatre Review 111 (Summer 2002): 74-75.

Frye, Northrop. The Anatomy of Criticism. New Jersey: Princeton UP, 1971.

"Généalogie"of Mary Ives. Longueuil, Quebec: SNJM Central Archives.

Girl Scouts. History of the Girl Scout Organization. "Girl Scout History." 2003. 12 April 2006 http://cheesecakeandfriends.com/troop1440/history.htm#History.

Girl Scouts. Official Web Site of Girl Scouts of the USA. "Girl Scouts Timeline." 2006. 1 December 2006 http://www.girlscouts.org/who_we_are/history/timeline/1912_1919.asp.

Gorman, Sister Mary. Telephone Interview. St. Mary’s Academy, Winnipeg. 13 May 2005.

Hall, Barbara. "The Professionalisation of Women Workers in the Methodist, Presbyterian, and United Churches of Canada." Kinnear 120-33.

Hoxie, W. J. How Girls Can Help Their Country. New York: Knickerbocker, 1913.

Hux, Allan, Fred Jarman, and Bill Geberzon. America A History. Toronto: Globe/Modern Curriculum, 1987.

Ignatiev, Noel. How the Irish Became White. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Jackel, Susan. "First Days, Fighting Days: Prairie Presswomen and Suffrage Activism, 1906-16." Kinnear 53-75.

"Jane Arminda Delano: Director of Army Nurse Corps." Arlington National Cemetery Website. April 2006. 18 April 2006 http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/jadelano.htm.

Jansen, Cassandra. "The Boston Teaparty." From the Revolution to Reconstruction Department of Alfa-informatica, University of Groningen. 2003. 27 March 2006 http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/E/teaparty/boston00.htm.

Jones, Maldwyn Allen. American Immigration. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1960.

Kealey, Linda. "Women and Labour During World War I: Women Workers and the Minimum Wage in Manitoba." Kinnear 76-99.

Kinnear, Mary, ed. First Days, Fighting Days: Women in Manitoba History. Regina: U of Regina P, 1987.

Longfield, Kevin. From Fire to Flood: A History of Theatre in Manitoba. Winnipeg: Signature, 2002.

Madden, Marie R. "Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary." Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 10. On-line edition, 2003. 7 May 2006 http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10678a.htm.

Malloy, Sister Margaret. "The History of St. Mary’s Academy and College and its Times." MA Thesis, University of Manitoba, 1952.

Marie, Julien. "Biographical notes on Sister M. Agnes." Manuscript.n.d.Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy Archives.

Meyers, Sister Bertrande. The Education of Sisters: A Plan for Integrating the Religious, Social, Cultural and Professional Training of Sisters. New York: Sheed and Ward, 1941.

"Minute Book." "Nominations locales 1904-1929." Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary of Manitoba Fonds. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Archives of the Saint-Boniface Historical Society/La Société historique de Saint-Boniface.

"Northwest Territories." Library and Archives Canada. 6 February 2006. 14 March 2006 http://www.collectionscanada.ca/confederation/023001-2245-e.html.

"Obituary." "Death of Sister M. Agnes (Mary Ives), Choir Sister." Sunday, 2 April 1939. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy Archives. Rpt. in Daniel Fischlin. Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare. 2004. 25 May 2005 http://www.canadianshakespeares.ca/multimedia/pdf/sister_magnes_obituary.pdf.

The Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre. Eds. Eugene Benson and L. W. Conolly. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1989.

Prentice, Alison, Paula Bourne, Gail Cuthbert Brandt, Beth Light, Wendy Mitchinson, and Naomi Black. Canadian Women: A History. Toronto: Harcourt, 1988.

Prentice, Alison, and Marjorie R. Theobald. "The Historiography of Women Teachers: A Retrospect." Women Who Taught: Perspectives on the History of Women and Teaching. Ed. Alison Prentice and Marjorie R. Theobald. Toronto: UTP, 1991. 3-33.

Revzin, Rebekah E. "American Girlhood in the Early Twentieth Century: the Ideology of Girl Scout Literature, 1913-1930." Library Quarterly 68. 3 (July 1998): 261-75. 3-33.

Rostecki, Randy R. , and Jackie A. Ritchie. St. Mary’s Academy. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1994.

Ruether, Rosemary Radford. "American Catholic Feminism: A History." Reconciling Catholicism and Feminism? Personal Reflections on Tradition and Change. Ed. Sally Barr Ebest and Ron Ebest. Urbana, Indiana: Notre Dame UP, 2003. 3-12.

Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary. "Milestones: Our History." 22 January 2006 http://www.snjm.org/EnglishContent/historymileeng.htm.

Thompson, John Herd. The Harvests of War. The Prairie West, 1914-1918. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1978.

United States Census Records. 1850, 1870, and 1880. 11 February 2006 http://www.ancestry.com/search/rectype/census/usfedcen/default.aspx.

Ward, Peter. White Canada Forever: Popular Attitudes and Public Policy Toward Orientals in British Columbia. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1990.

Williams, Dave. Misreading the Chinese Character: Images of the Chinese in Euroamerican Drama to 1925. New York: Peter Lang, 2000.

Wilson, Woodrow. "President Wilson’s Declaration of Neutrality." 19 August 1914. Brigham Young University Library. October 2006. 10 May 2006 http://www.lib.byu.edu/~rdh/wwi/1914/wilsonneut.html.

Sister Mary Agnes: Bibliography of Plays

Agnes, Sister Mary. The Arch of Success. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1919.

—. "At the Court of Isabella." The Last of the Vestals and Other Dramas. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1914. N.p.

—. The Bandit’s Son. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. "The Best Gift." The Best Gift and Other Short Plays. Winnipeg, St. Mary’s Academy 1923. 4-18.

—. Better Than Gold. Winnipeg, St. Mary’s Academy, 1922.

—. "The Birthday of the Divine Child." The Best Gift and Other Short Plays. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1923. N.p.

—. The Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne: Victims of the French Revolution. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. Children of Nazareth. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1926.

—. Choosing a Model: A Dialogue for Commencement Day. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1914.

—. Christmas Guests: A Christmas Play for Girls. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1915.

—. Cross and Chrysanthemum. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1922.

—. "Crown For the Queen of May." Catholic School Journal 28. 1 (April 1928): 23-4, 26.

—. A Day in June. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. A Day with Peggy. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. "The Divine Guest." The Best Gift and Other Short Plays. Winnipeg, St. Mary’s Academy, 1923. N.p.

—. The Empress Helena or The Victory of the Cross. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1915.

—. The Eve of St. Patrick’s. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. "Forgotten Gifts: A Playlet for Thanksgiving Day." Catholic School Journal 28. 5 (October 1928): 227-8.

—. A Happy Mistake. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1924.

—. "Harvest of Years." (manuscript). Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1924.

—. How St. Nicholas Came to the Academy A Christmas Play For Little Girls. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1914.

—. An Irish Princess. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1917.

—. Katy Did. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1926.

—. The Last of the Vestals: A Historical Drama For Girls. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1914.

—. "Legend of the Two Altar Boys." Short Plays and Recitations. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1922. N.p.

—. "Little Cinderella." Short Plays and Recitations. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1922. 4-13.

—. Little Saint Teresa. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1923.

—. Mabel’s Christmas Party. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. Making Santa Claus a Missionary. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. Miracle of Saint Bride. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. Mary Magdalen. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1918.

—. Mary Stuart and her Friends. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1918.

—. "A May Festival." The Best Gift and Other Short Plays. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy 1923. N.p.

—. The Millionaire’s Daughter. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1915.

—. Mother’s Birthday. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1921.

—. "The New Governess." Short Plays and Recitations. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1922. 17-30.

—. "New Year’s Eve." Short Plays and Recitations. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1922. 31-37.

—. Old Friends and New. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1917.

—. Our Japanese Cousin. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. The Paschal Fire at Tara. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. "A Patriot’s Daughter." The Last of the Vestals and Other Dramas. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1914. 113-137.

—. Pearls for the Missions. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1923.

—. Plans For the Holidays: A School Play For Closing Exercises in the Grammar Grades. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1915.

—. "The Point of View." Short Plays and Recitations. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy 1922. N.p.

—. "Pontia, Daughter of Pilate." N.p., n.p., 1928.

—. Queen Esther. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1924.

—. The Queen of Sheba. A Biblical Drama. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1915.

—. The Queen of Sheba and Other Dramas. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1914.

—. The Red Cross Helpers. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1918.

—. A Rose From the Little Queen. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. Rose of Canada. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. "St. Patrick’s Medal." N.p., n.p., n.d.

—. St. Patrick Speaks. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. Saint Teresa’s Roses. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. Schoolgirl Visions. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1923.

—. Sense and Sentiment. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1920.

—. A Shakespeare Pageant: Dialogue for Commencement Day. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1915.

—. A Shower of Roses. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. The Step-Sisters. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1917.

—. Sweetness Came to Earth. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. "The Spoiled Statue." Short Plays and Recitations. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1922. 38-39.

—. The Taking of the Holy City. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1918.

—. "Those Shamrocks From Ireland." The Last of the Vestals and Other Dramas. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1914. N.p.

—. Their Class Motto: Duty First. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. Three Gifts for the Divine Child. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, n.d.

—. "The Trial of the Weather." Short Plays and Recitations. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1922. 14-16.

—. "Ugly Duckling." Catholic School Journal 25? (April 1925): 31-2.

—. "Uncle Jerry’s Silver Jubilee." The Best Gift and Other Short Plays. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy 1923. N.p.

—. "Valedictory." Short Plays and Recitations. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy 1922. 44-45.

—. "Visit of the Magi: a Christmas plays for boys." Catholic School Journal 33? (December 1933): 287-8.

—. "Way of the Cross." N.p., n.p., 1921.

—. "When All Were Wrong But Me." Short Plays and Recitations. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1922. 42.

—. The Young Professor. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1927.

—. Zuma, the Peruvian Maid. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1922.

Notes