Article

Rhizomatic Challenges to Compartmentalization:

Rewriting in Anne Carson’s Decreation and Patience Agbabi’s Telling Tales

A meaning spins, remaining upright on an axis of normalcy aligned with the conventions of connotation and denotation, and yet: to spin is not normal, and to dissemble normal uprightness by means of this fantastic motion is impertinent. . . . To catch beauty would be to understand how that impertinent stability in vertigo is possible. But no, delight need not reach so far. To be running breathlessly, but not yet arrived, is itself delightful, a suspended moment of living hope.

— Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet (xi)

1 Anne Carson’s Decreation: Poetry, Essays, Opera (2005) and Patience Agbabi’s Telling Tales (2014) address similar concerns on a technical level, yet both collections have not been mentioned in the same breath. It is undeniable, however, that the authors share a penchant for formal experimentation: Carson is a Canadian poet, essayist, novelist, translator of Ancient Greek, and classics scholar whose trademark is often considered to be “unclassifiability” (Wilkinson, Introduction 1), whereas Agbabi is mostly known as a British-born unorthodox performance poet of Nigerian origin. Some critics go so far as to suggest that “perhaps one reason Agbabi was canonised among the ‘Next Generation’ poets in 2004 involves her at times traditional, a priori situation of form before content” (Huk 231). Equally, Carson is notorious for “wear[ing] her brain on her sleeve,” as Daphne Merkin has observed, while Agbabi’s literary roots as an Oxford-educated poet similarly influence her poetry. What makes Carson and Agbabi an especially apt pairing, therefore, is their shared intellectual concern with the non-binary and the fraying edges of formal categories. Being relatively recent, the literary works that I scrutinize here have received little critical attention. The few studies on Decreation — including Cole Swensen’s and Johanna Skibsrud’s essays on radical self-externalization and the decreative act of writing, respectively; Dan Disney’s article on the feminine sublime; and Elizabeth Coles’s analysis of Carson’s engagement with the French philosopher and mystic Simone Weil — have mainly approached Carson’s collection from a spiritual angle, whereas Agbabi’s boundary crossing is generally addressed within the context of challenging the socially constructed categories of race and gender (e.g., Coppola, “Queering” and “Tale”; Huk; Ramey). Although these approaches are thematically appropriate, in this essay I propose a comparative reading of both works with the purpose of highlighting their formal aesthetics. The rationale for this comparison is twofold. First, following recent changes in Canadian literary studies in which literary works are no longer read solely in a Canadian context (see Kamboureli 1-2), such a comparative analysis seeks to shift attention to emerging transnational developments, all the more so since Carson’s work “features few explicitly Canadian settings, characters, or homages to Canadian artists” (Rae, “Verglas” 164) — and Decreation is no exception in this regard. Second, I hope to redress the gap in the literature on these authors’ works from a semiological perspective. In keeping with Carson’s critical attitude to the tendency to compartmentalize knowledge, I aim equally to contribute indirectly to a better understanding of how “Black British . . . [literature] has never been purely and simply about ‘Black British’ issues, despite criticism which sometimes seems to suggest otherwise” (Welsh 179).1

2 In what follows, I explore both collections from the perspective of the text-constructing subject in order to reflect on formal literary developments in this hyperconnected digital age. Such an approach is necessitated by the aesthetic strategies adopted in both works. For instance, Agbabi’s tale “100 chars” consists of “stanzas” restricted to a hundred characters each in accordance with the formal constraints imposed by the social media platform Twitter (Hsy 98). Moreover, Telling Tales is realized across disparate media: online on Agbabi’s blog entitled Telling Tales: Rewriting the Canterbury Tales, in print as a full-length collection, and live as a reading-in-transit (Barrington and Hsy 138). Carson similarly writes across a wide range of genres and media in Decreation: not only does the collection consist of poems, four essays, a cinematic shot list, a screenplay, a pseudo-interview, an ekphrastic poem, and an opera and oratorio libretto, but also it includes a still, a reproduction of a drawing, and a photograph. In this light, Jim McGrath has posited that Carson’s approach to literature “challenges, implicitly and explicitly, certain cultural assumptions and standards of reading applied to [her] chosen literary form” (18). My reading takes McGrath’s statement as a constructive starting point to argue that Carson’s and Agbabi’s diverse collections should be regarded first and foremost as projects of rewriting that challenge perceived understandings of literature by pivoting on a rhizomatic logic.

3 To this end, my literary analysis hinges on a literary semiology in the tradition of Ferdinand de Saussure, in contrast to that of Charles Sanders Peirce, since I am concerned with the internal constitution of the sign, or the literary work, rather than with stand-for relations (see Kress 41). Moving beyond the limitations of biographism — often counterproductive since it can result in intentionalism or reduce authors who do not fit the white male paradigm to sociological informants — the semiological reasoning that I develop throughout this essay accordingly aims at elucidating the literary strategies underlying interpretation and “meaning” in literature. In this way, it is able to bypass the pitfalls of projection that often accompany the use of external, reductive methods imposed on literary texts. The main limitation of this approach, however, is that it can postulate the existence of a so-called model reader, in the sense that it might “wrongly assum[e] agreement among readers or pos[it] as a norm a ‘competent’ reading which other readers ought to accept” (Culler 55). In addition, it is disputable that, first, a literary work constitutes an act of signification and, second, that these effects of signification can be pinpointed (Culler 53). It is therefore crucial to emphasize that the semiological analysis that I conduct here seeks to shed light on the signification strategies inherent in the interpretation of Carson’s and Agbabi’s works without addressing the extent to which readers might agree in their literary interpretations (see Culler 55). The significance of my argument, therefore, lies in its methodological pursuit of unearthing signifying processes at the root of literary interpretation, thereby offering a processual perspective on meaning making in literature.

Probing the Limits

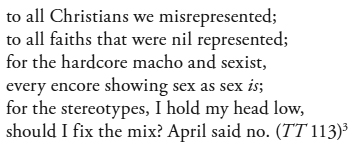

4 Drawing on such a literary semiology, I situate Agbabi’s and Carson’s collections as rhizomatic rewritings that question “compartmentalized” thinking about literature by refuting false dichotomies. Guided by principles such as connection and multiplicity (Deleuze and Guattari 7-8), both authors’ rhizomatic engagements with the notion of rewriting communicate and open up the confines of categorization on a number of discrete levels with the aim of unsettling binary oppositions. In the case of Carson’s Decreation, such rhizomatic thought manifests itself in her “Venn diagram type of engagement” (Wilkinson, Introduction 5) that demonstrates all possible relations and thereby results in the lack of an interpretative centre, thematically expressed in the collection’s spiritual “dream of distance in which the self is displaced from the centre of the work and the teller disappears into the telling” (DC 173).2 Agbabi’s Telling Tales, on the other hand, reconfigures Geoffrey Chaucer’s classic into a “slam anthology” that draws on numerous intersections bridging past and present in politically correct Britain:

In this regard, it is crucial to note that both collections emphasize the importance of interpretation at the heart of any textual engagement. Carson asserts that “in the end it is important not to be fooled by fake women. If you mistake the dance of jealousy for the love of God, or a heretic’s mirror for the true story, you are likely to spend the rest of your days in terrible hunger. No matter how many pages you eat” (DC 181; emphasis added). In this way, she juxtaposes critical readings of texts with literalism or blind “consumptions” of literature. Likewise, Agbabi’s collection offers a metareflection on the need for constant reinterpretation by reminding the reader that “Chaucer Tales were an unfinished business” (TT 2).

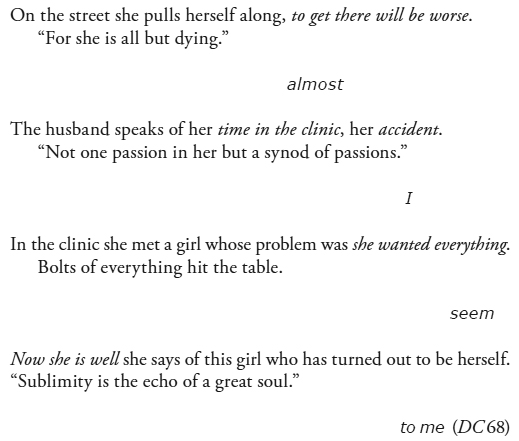

5 In Decreation, this idea of hermeneutic responsibility is translated into a continual re-engagement with the central notion of decreation by means of a succession of analogies, since for Carson every “idea must be perpetually rewritten, re-understood, re-transformed” (Thorp 23). Not only is “decreation” the title of both the collection as a whole and an individual essay and accompanying opera libretto, but Carson also creates reverberating echoes of disintegration throughout the work by clustering together elements that seem to be irreconcilable yet evoke a palpable sense of decreation upon closer examination:

By condensing the idea of a dreamlike fog, a morbid scenery, the crushing incomprehensibility that is everything, and fearful visions of clarity into a vortex of thought, Carson’s method of juxtaposition coaxes the reader into searching for a new understanding of these distinct entities that can generate a comprehensive interpretation of the text. This tortuous questioning of supposedly disparate elements — that is, answering the question, what is the connection? — is intricately tied to the deconstructive and hence reinterpretative nature of the collection. As Ian Rae has remarked, the “clarity of Carson’s work is enhanced, not obscured, by this circuitousness because each variation of the . . . motif is like a lens magnifying the significance of the preceding and succeeding variations” (“Verglas” 165). These variations of the central trope of decreation thus make for a sense of stability that counteracts the collection’s para-tactic complexity. Although Decreation is made up of juxtapositional leaps of thought and speech demanding an “interrogation of the possible correspondences or resonances between the disjunctive and the fragmentary” (Friedman 37), the many echoes suffuse the work with a mythical conception of time that imagines a continuity between past and present, as the short poem “No Port Now” succinctly demonstrates:

This mythical understanding of time is also alluded to in the collection’s oratorio libretto titled “Lots of Guns” (105-14), in which the mythic, curious past plays a central role.

6 Similarly, Telling Tales is a twenty-first century re-engagement with Chaucer’s fourteenth-century Canterbury Tales featuring Harry “Bells” Bailey, who organizes a poetry slam for a travelling group of pilgrim poets with tales ranging “from the grime to the clean-cut iambic, / rime royale, rant or rap” (TT 1). More specifically, the rewriting takes the form of a contemporized series of poetical narratives set in multicultural Britain on a Routemaster bus travelling from London to Canterbury Cathedral while still being rooted in a medieval literary tradition. By updating the gender and racial differences — Telling Tales features as many male as female poets of Nigerian, Zimbabwean, Singaporean, Indian, Caribbean, Canadian, French, Welsh, Scottish, Irish, and English descent (TT 115-20) — Agbabi makes the collection more widely applicable. However, it is important to bear in mind that, though Chaucer is often regarded as the founding father of English national poetry, he lived in a society in which the notion of Englishness was still emerging and transnational contacts and cross-cultural encounters were common (Coppola, “Queering” 374; Coppola, “Tale” 308-09). It could thus be argued that, by rectifying the gender and racial imbalances, Telling Tales approaches a postcolonial rewriting by “interrogating the philosophical assumptions on which [Chaucer’s] order was based” (Ashcroft et al. 32). However, Agbabi complicates this process of revision: Telling Tales is not merely double layered by virtue of being a rewriting but also multilayered because of the representation of various positions generally believed to be mutually exclusive. More concretely, Carson and Agbabi create complex counterpoints of competing frames and perspectives that allow them to rewrite their objects of inquiry — the notion of decreation in Carson’s case, Chaucer’s portrayal of Britain in Agbabi’s case — from oblique angles. To this end, they rely on several strategies of signification, which include generic hybridity, multimodality, and polyphony.

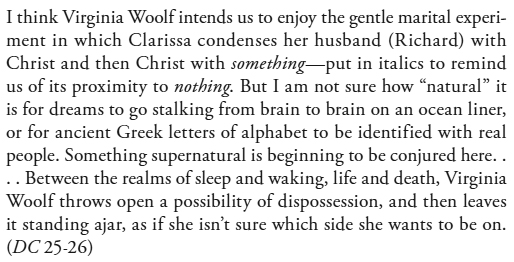

7 In more specific terms, Carson’s Decreation is characterized by an intergeneric quality that derives from her interweaving of supposedly distinct genres and that thereby coaxes readers to rethink their frames of reference. Accordingly, the notion of genre is conceptualized here as a tool in accordance with Stine Lomborg’s understanding of the term, namely as a socio-cognitive orienting device or knowledge structure that can be negotiated (42). A significant illustration of this generic hybridity is the genre modelled on Carson’s writing style, namely the lyric essay (Rae, “Verglas” 166), since it is both discursive and rooted in scholarly observation while melding its allegiance to (fictional) autobiography, reflected in poetically inflected — often metaphysical — musings (Moran 1279). According to Joe Moran, the genre is thus able to capitalize on what he calls a “seam between raw experience and considered reflection” (1293). Although Moran asserts that what he terms “essayistic nonfiction” seeks to correct the pseudo-knowledge and emotional oversharing characteristic of our digital age (1287, 1293), I argue that the imaginative dimension of Carson’s lyric essays not only provokes consideration of the boundary between factually grounded analysis and metaphorical modes of thinking but also demands a more nuanced understanding of human experience seamlessly coalescing thought and feeling:

Although Carson’s writings are founded on textual evidence, as Moran’s term indicates, they are nevertheless imbued with a fictional strain that flows naturally from her extended riffs. Carson usually starts with a piece of writing that she submits to a rigorous analysis, but her analyses then seemingly evolve into personal meditations and projections as she stops providing source references, thus effectively blurring the line between fact and fiction, essay and literature, observation and imagination:

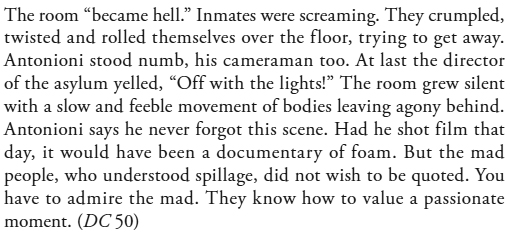

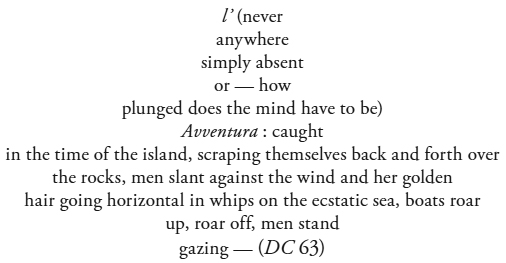

8 Perhaps not so surprising for a work titled Decreation, Carson’s collection highlights the importance of acknowledging the (deconstructive) meaning potential inherent in the interplay between modes — in this case the visual mode, and the verbal mode — since its materiality, in Gibbons’s words, “induces the two semiotic modes to collaborate in the literary act, and thus both the verbal and [the] visual influence the reader’s creation of, and potential immersion in, an imagined text-world” (114). Through Carson’s skilful use of images, typography, and layout, the reader’s total immersion in the fictional world is hampered, as illustrated by the following excerpt from “L’ (Ode to Monica Vitti)”:

By thus embedding the conceptual juxtaposition characteristic of human consciousness in its visual-textual dynamics, Decreation points its readers toward the materiality of the medium. In this way, the collection’s multimodality galvanizes readers to re-evaluate how meaning in literature comes about by encouraging them to look for an integrative understanding of the text that unites both modes: that is, word and vision. In other words, the act of reading becomes a distinctly affective practice as Decreation foregrounds the role of the body, and more specifically that of eye movement, in the reading process. The act of reading becomes a decreative effort as readers are confronted with the struggle to reconcile both modes within a unity of experience and thereby to make sense of the narrative:

As this excerpt from “Mia Moglie (Longinus’ Red Desert)” demonstrates, Carson not only embeds speech representation and focalization in the visual-textual dynamics but also juxtaposes multiple reading paths and thereby lays bare the divide between the tangible world of the page and the virtual world beyond the textual surface.

9 Before proceeding to examine Decreation’s “polyphonic quality,” I should clarify exactly what is meant by this term. I use the term “polyphony” here specifically to refer to “a plurality of independent and unmerged voices” that are “not only objects of authorial discourse but also subjects of their own directly signifying discourse” (Bakhtin 6, 7). Put differently, the characters’ voices are autonomous in the sense that both characters and narrators (or speakers) are equally entitled to speak (Vice 112). In the context of this discussion, Decreation tacitly challenges notions of overt authorial control since Carson’s use of personae results in a blurring of identity between the speaker — most prominent in the essays and therefore likely to be mistaken for the author — and the plethora of voices in the accompanying literary experiments. For example, Carson first devotes her essay on the sublime to the ancient literary critic Longinus, who then resurfaces in the first sublime of the collection titled “Longinus’ Dream of Antonioni,” in which the narrative voice is skilfully shaped by a merging of identity between Longinus and the narrator, probably assumed to be Carson herself following her previous essay on the sublime: “Long bright dream of waking beside a man bleeding from the eyes. Clots of blood on his face and through the bedclothes and him not inclined to take it seriously. . . . He returned saying the doctor gave him only winks and ribald jokes about ‘going courting.’ Sad now I turned my attention to the coffee pot with its missing parts and melted cord” (DC 61; emphasis added). Although it seems to be probable enough that a reader would assume Longinus to be the speaker of the opening sentences in accordance with the sublime’s title, the final sentence — and especially the seemingly trivial reference to the broken coffee pot — casts doubt on the whole account, as if the “real” speaker suddenly wakes up from a daydream. In this respect, Rae contends that Carson approaches gender as a question of genre as her various fictional disguises allow her to examine the potential of diverse perspectives on the one hand and thereby to mould the reader’s perception of the author’s personality on the other (Cohen 248, 251).

10 It is important to consider, however, that the collection’s principal essay is centred on the lives of three women who “had the nerve to enter a zone of absolute spiritual daring” (DC 179). In this regard, Rae’s related observation that Carson’s “feminist enquiries devote attention to the lives of childless female intellectuals (Dickinson, Stein, Woolf), or married women whose behaviour departs from normative maternal roles (Sappho)” (Cohen 254), is telling, especially since all these women are featured in Decreation. From this socio-historical perspective, therefore, it could be argued that Decreation is a work of recuperation that attempts to “re-evaluate forgotten or neglected texts by women” (Hawkins 156). The following passage from Carson’s essay on decreation gives weight to this suggestion:

Accordingly, Carson advocates a more inclusive intersubjective space by inviting her readers to put their own “survival” aside and not pass judgment on literary works on the basis of entrenched categories such as the author’s gender. The collection concomitantly highlights the ability of language to convey the prevailing hegemonic patterns and thereby obliquely exposes the dangers of binary thinking.

Rhizomatic Constructivism

11 The rejection of fixed oppositions thus aligns Carson with postcolonial writers (see Coppola, “Tale” 307) by privileging a rhizomatic logic based on relation. This kind of rhizomatic reasoning, as theorized by Édouard Glissant, challenges totalitarian notions of rootedness by promoting an enmeshed root network “in which each and every identity is extended through a relationship with the Other” (11). This inclusive approach seems to be particularly fitting for my reading of Agbabi’s Telling Tales. Equally significant to my discussion and related to this approach is Stuart Hall’s observation about a shift in Black cultural politics from “a struggle over the relations of representation to a politics of representation itself” (224),4 which also implies the demise of essentialist categorizations since it involves “the recognition that ‘black’ is essentially a politically and culturally constructed category” (225). By foregrounding the constructed nature of her collection, for example through occasional metafictional references to the pilgrims’ writing of the tales in the prologue and epilogue, Agbabi not only highlights the creative process of representation (see Tönnies et al. 308) but also paves the way for new modes of (literary) expression.5

12 By dismissing all dichotomies, Agbabi can be said to have made the embracing of a “continuum of experience” her modus operandi (Coppola, “Queering” 373). In the context of her intergeneric practice, this inclusive trait finds expression in her relation to the apparent dichotomy between the spoken word and the written word as well as her amalgamation of poetry and prose fiction in Telling Tales. Critics have often noted that Agbabi’s works counteract the prevailing notion that live performance and written poetry are in counterpoint with each other (e.g., Ramey 319). Although such a claim seems to be indefensible in light of the problematic idea of medium specificity, Lauri Ramey elaborates her statement by asserting that Agbabi seeks to “restore the genre of lyric poetry to its origins in sound and music, while maintaining the discipline of form and technique that comes from viewing a poem as an artefact to be read on the page” (320; emphasis added). In this way, Agbabi effectively moves beyond the false dualism between rigid form and spontaneity, or tradition and innovation (see Ramey 319), thereby reminding the reader that “pigeonholing performance poetry in one category [as a distinctly oral literary genre] has already been a fallacy to begin with” (Tönnies et al. 318). In this light, critics generally regard Agbabi’s work as performance poetry because of her skilful use of interalia, monologues, rhythmic devices, and returning patterns (e.g., Novak 83-84).

13 A serious weakness with this argument, however, is that it does not take account of the medium at issue, namely the medium of the printed text. In other words, the work under scrutiny here is a written transcript of performance poetry. In this respect, Agbabi’s statement that “I was writing a book. It was very important that people were able to read this and hear it in their own heads” (qtd. in Runcie) only adds to this complexity. Therefore, it seems to be more appropriate to use terms that underscore the intermedial quality of Agbabi’s literary praxis,6 such as “narrative poetry” or “poetical narratives.” More significantly in the context of my semiological analysis, live performances allow Agbabi to hone her written poems in terms of the affective responses that they evoke, enabling her to “feel that visceral response” (Agbabi, qtd. in Runcie). This idea becomes even more pertinent when considering that “the prevalent public stereotype of Black British poetry since the 1970s has been that it is limited to political themes and weakened by its primarily performative mode” (Welsh 179; emphasis added). Moreover, it is noteworthy that Carson achieves a similar effect in Decreation through her opera and oratorio librettos. Both authors thus thrive on the nexus between the spoken word and the written word: Carson to unsettle readers’ expectations by presenting a series of typographic experiments as if they were designed to be sung, Agbabi to achieve a more sustained engagement with the text by the reader. Yet, by doing so, both effectively demonstrate that the notion of medium specificity has become unsustainable.

14 Echoing Kathleen Kuiper’s remark that “Carson’s genre-averse approach to writing mixes poetry with . . . prose,” I would argue that Agbabi’s collection refutes simple categorization by straddling generic boundaries. Whereas Carson’s lyric essays pave the way for a re-evaluation of the established modes of thinking, feeling, and, by extension, writing, Agbabi’s work crosses several genres by combining the formal techniques characteristic of lyricism with a penchant for innovation and experimentation (Coppola, “Queering” 372). With this in mind, I propose to conceptualize Telling Tales as a work of poetic fiction or, in more precise terms, as a verse novel. After all, as a subgenre of narrative verse, the verse novel’s oral character derives from the frequent use of dramatic monologues (Addison 30, 35), particularly apt in the context of this orally inspired collection of tales. Furthermore, such works often follow the conventions of the realist novel since they are usually easily accessible in the sense that they aim at readability while generally being characterized by a high degree of verisimilitude and uncomplicated, sometimes colloquial language (Addison 17-19, 35). Although the verse novel is a novelistic genre because of this social orientation, Catherine Addison asserts that it is “first and foremost a poem” (19), where its hybrid character comes into play. More concretely, these novels display the visual and prosodic characteristics of verse insofar as they make use of lineation — a typographical feature characteristic of verse — as well as metre and rhyme (19, 35). Telling Tales meets these criteria as a socially diversified collection of tales that not only is infused with popular culture through, for example, rap-, grime-, and punk-inflected narratives (see Novak and Fischer 353-59), but also includes verse writings in Chaucer’s rhyme royal and his heroic couplets, combined with poetic forms such as the sestina, the sonnet corona, and the mirror poem. Consider, for example, the first stanza of the sestina titled “Emily” (TT 5; ellipsis in the original), in which Agbabi rewrites the love triangle among Palamon, Arcite, and Emelye (here spelled Emily/Arc/Pal) by turning both men into Emily’s alter egos:

Crucially, Agbabi uses J.R. Hulbert’s statement that “in Chaucer’s story there are two heroes, who are practically indistinguishable from each other, and a heroine, who is merely a name” as an epigraph to the tale (qtd. in TT 5), which indicates that the heroine’s central role in Agbabi’s rewriting is not inconsequential. In this sense, Ramey rightly notes that Agbabi “has uniquely succeeded in fusing British literary tradition — historically associated with white male privilege — with contemporary modes of entertainment that are often associated with popular culture and artists of the African diaspora” (316). As a result, Telling Tales convincingly disputes the apparent divide between “high” and “low” art, literature, and entertainment while bridging racial and gender differences.

15 Agbabi thus creates a protean collection at the crossroads of slam, poetry, and narrative, thereby defying fixed oppositions and giving prime position to a concerted literary work based on relations not only between the “original” and her rewriting but also between socio-cultural and gender identities. By having her work printed, however, Agbabi adds another layer to the already hybrid genre of the verse novel by drawing attention to the visual aspect of reading. In other words, like Decreation, Agbabi’s collection capitalizes on the materiality of the medium since some narratives rely on a haptic aesthetic requiring physical interaction with the page. Agbabi’s use of typography illustrates this point clearly. For instance, the subtitle of “Artful Doggerel: Sir Topaz vs Da Elephant — Round 3” is printed in boldface type (TT 83-85), which can be considered an example of typographical iconicity since the signifier here (i.e., the feature of boldface or visual salience) resembles the signified by “convey[ing] the sonic salience of someone shouting” (Nørgaard 118), appropriate for this slanging match. Similarly, in “The Gospel Truth” (TT 109-11), the seven deadly sins are printed in majuscules in keeping with the Parson’s preaching, and in “That Beatin’ Rhythm” (TT 49-53), the extensive use of capital letters evokes a sense of pulsation. As another case in point, the use of regular or italic type in “Artful Doggerel” correlates with the speech representation of Sir Topaz and Da Elephant, respectively, thus necessitating engagement with the materiality of the medium for the narrative to progress.

16 “Reconstruction” is arguably the clearest example of Agbabi’s use of multimodality (TT 69). Not only do certain words resemble snippets from a blackmail letter or newspaper in accordance with the tale’s content, which concerns a news item, but these snippets in a different font and the words in superscript also form two additional messages, presumably those communicated by the mother and father, respectively, of the beheaded girl. Likewise, as Candace Barrington and Jonathan Hsy point out, Agbabi’s deft use of punctuation and capitalization in her mirror poem titled “Unfinished Business” creates two stanzas with opposite meanings (142). This ambiguity in turn echoes the indecisiveness of the title:

Another example of what is meant by the collection’s multimodal organization is Agbabi’s use of layout. According to Nina Nørgaard, line length or visual space is often employed to convey meanings related to time, whereas blank spaces generally denote aural silence (120). Thus, in the tale with the telling title “Fine Lines,” the staccato rhythm evoked by phrases such as “you // knew // blue” (TT 57), and the use of multiple blank spaces between words, as in “in the future leaving” (TT 59), together evoke an apt sense of heartache and of running out of time characteristic of hindsight.

17 Sarah Welsh has recently posited that Telling Tales is voiced by a “cast of . . . fully imagined speakers who satirically capture the zeitgeist of the contemporary British poetry scene” (190). Although it remains to be established whether the collection can be regarded as a satire composed of fully imagined voices, as the example of Mrs Alice Ebi Bafa will demonstrate, Agbabi does achieve a sense of cultural immediacy by combining slang and textspeak with standard as well as regional varieties of English, including Geordie, Yorkshire, Scottish, Welsh, and London-based voices (Novak and Fischer 360; Runcie). “Sharps an Flats” illustrates this first point clearly: J., murdered because he kept singing the “Alma Redemptoris Mater,” writes to his mother that he is “chattin on a mix made / in Heaven, don’t hit the fade switch b4 it’s played: / remember, used 2 have perfect pitch but my pitch paid / a rich trade when I got cut off by a switchblade” (TT 81). The sonnet corona “Joined-Up Writing,” which revolves around a mother whose “son’s a writer, aye, but he’ll not write / to [her], his poor old mam” (TT 21), showcases Britain’s regional variety. Because of these frequent allusions to the acts of writing and telling stories, I would argue that Welsh’s previous statement indirectly draws attention to the collection’s meta-fictional tendencies while also highlighting the (ultimately) fictional nature of its speakers. After all, Telling Tales questions notions of overt authorial control by complicating the relationship between fiction and nonfiction, similar to Carson’s identity play in Decreation. Yet, where Carson blurs the distinction between the author-speaker and voices both mythical and historical (yet sometimes fictionalized), Agbabi questions the fictional status of her speakers by including author biographies at the end of the collection. To complicate this process further, the speakers themselves sometimes take on a fictional persona, such as the monkey in “100 chars” (TT 88-90), the fox in “Animals!” (TT 91-93), or the sniffer dog in “Tit for Tat” (TT 11-14).

18 It is undeniable that Agbabi occasionally introduces the intention of an author figure, as in “our intent was to showcase this island’s / love of retelling tales in its fierce pun” (TT 113). I therefore dispute the claim made by Merle Tönnies and colleagues that Agbabi “pretend[s] that there is no ‘conceptual split’ (Novak 2011, 192) between the performer and the lyrical I” by “project[ing] fictionalised versions of herself in an age where the author is supposed to be dead” (Tönnies et al. 316, 310). Rather, similar to Carson’s evocation of an “identity collage” that guides the reader’s perception of who Carson is in real life (Rae, Cohen 251), Agbabi seems to be highly skilled at convincingly adopting multiple personae by rewriting her own (cultural) identity. In short, her collection is not merely “a ‘subversive’ commitment to form,” as Manuela Coppola points out, but first and foremost “a ‘performance space’ where a broader definition of identities can be staged” (“Queering” 380). Agbabi’s rewriting of “The Wife of Bath’s Tale” is possibly the clearest example of this identity play, since the choice of Nigerian English — formal, educated West African English — over Nigerian Pidgin expresses Mrs Alice Ebi Bafa’s cross-culturality (Agbabi, “Stories”). Yet it is important to bear in mind that Ebi Bafa remains a fictional persona since Agbabi herself does not speak Nigerian English despite her Nigerian ancestry (see Novak and Fischer 356). This kind of rhizomatic boundary crossing in terms of identity and, by extension, form can be related to Carson’s advocacy of a more inclusive intersubjective space as both authors take on multiple personae and thereby work through intersections between socio-cultural identities.

Conclusion

19 When asked if she considered the fact that her works need sections on their own to be a problem, Carson replied that this is “not a problem but a question: What do ‘shelves’ accomplish, in stores or in the mind?” (qtd. in Rae, Cohen 223). The semiological analysis that I have developed here has revealed that Carson’s and Agbabi’s collections should be considered projects of rewriting that probe their objects by relying on unsettling relations and that thereby displace the need for an interpretative centre or “original.” More precisely, their works demonstrate that any re-engagement with the past calls for both creativity and responsibility since their use of signifying strategies disrupts how contemporary literature is conceptualized and, consequently, compartmentalized. In short, their acts of rewriting amount to a process of revisioning since both authors challenge essentialist thinking about identity, difference, and, by extension, literature through their use of generic hybridity, multimodality, and polyphony. Poetry and (non-) fictional prose, the spoken word and the written word, the visual mode and the verbal mode, fiction and nonfiction, authorial presence and fictional disguise are not diametrically opposed but generate rhizomatic alternatives to ingrained patterns of thinking. This acentric, inclusive stance combines an experimental approach to form with an increased awareness of the constructedness of all categories.

20 In more general terms, these collections can be seen to throw partial light on how literary works “instantiate the cognitive shift in their aesthetic strategies” (Hayles 197). According to N. Katherine Hayles, a generational shift from deep to hyper-attention is under way as a result of growing exposure to stimulation, particularly increasing media consumption, which should be understood as an increase in the types of media, the tempo of visual stimuli, and the complexity of interlaced plots (188-91). Crucially, Carson’s and Agbabi’s rewritings not only question the notion of medium specificity but also include multimodal elements and present different viewpoints by virtue of their polyphonic character. Hayles then distinguishes between two cognitive styles, namely deep and hyper-attention, and correlates deep attention — the cognitive mode typically associated with the humanities — with a single information stream and long focus times, making the style especially useful in the context of complex problem solving within a singular medium, though it thereby compromises flexibility of response (187-88). Hyper-attention, in contrast, is particularly valuable when interaction and negotiation are required by leaning toward multiple information streams and a high degree of stimulation (187). In the context of Carson’s and Agbabi’s collections, the analysis thus suggests that the numerous information streams characteristic of hyper-attention manifest themselves in a rhizomatic rewriting that pivots on multiple relations of connection and thereby uproots dualistic conceptions of literature and storytelling in general. In other words, this postmodern process of deconstructing limiting labels can be related to a general shift toward hyper-attention. As a result, readers are propelled into a constant negotiation with — and hence a re-evaluation of — various frames of reference on a conceptual level. Agbabi already knew as much when she stated that she “didn’t want to just regurgitate the original” (qtd. in Runcie). By recuperating these authors’ works for their aesthetic strategies within a broader techno-cognitive movement, I have shed new light on how their rewritings succeed in decreating differences, which, as Carson aptly remarks in Decreation (178-79), differs considerably from obliterating distinctions altogether.

Author’s Note

I thank Elisabeth Bekers, whose input helped me to develop the ideas presented in this essay.