Article

Hearing Zong!

Choreosonographies of Silence

Zong! is its own raison d’être — although it comes out of the European archive, it is not a reaction or response to Empire. It simply is. As lamentation, mourning song, extended wake.

— M. NourbeSe Philip, Bla_k (341)

Hardly anterior to language and therefore the human, these rumblings vocalize the humming relay of the world that makes linguistic structures possible, directly corresponding to how the not-quite- and nonhuman give rise to the universe of Man.

— Alexander Weheliye, Habeas Viscus (127)

Zong! provides a future.

— Katherine McKittrick, “Diachronic Loops” (14)

1 In this essay, I consider M. NourbeSe Philip’s 2008 poem cycle Zong! as a form of lament. Lament offers a theoretical and formal vocabulary comprising grief, grievance, antithesis, and antiphony. I argue that Philip articulates not only a plaint (grief) for the African captives murdered in the 1781 Zong Massacre but also a complaint (grievance) irreducible to the anti-Black grammars that structure the present. Philip writes through the sole public document of the Zong Massacre, Gregson v. Gilbert, setting the two-page court report against and through itself (antithesis) to respond to the calls of the African captives who exist at the centre of the document (antiphony). Zong! is thus not a reaction to coloniality; rather, the poem antiphonally responds to the African presences that have always existed within the document. In what follows, I position Zong! as a sequence of sound writings — entanglements of sound, movement, silence, and noise — that materializes presences in excess of Gregson v. Gilbert. I read Zong! as a material and extralinguistic affirmation of Black life that imagines and sounds new forms of being. Supplementing the critical tendency to understand the poem’s intensifying caesurae as routes of linguistic mediation, I acknowledge these spaces as rumblings from the future that sound on frequencies beyond the sonic grid of the present.

“the air is dangerous with sound”

Silence does not always mean an absence of sound.

— M. NourbeSe Philip, Looking for Livingstone (51)

2 Toward the end of “Notanda,” the essay that concludes Zong!, Philip describes her poem cycle in terms of a subaquatic lament, an antiphonal accompaniment to the unceasing clamours that ring out beneath Atlantic waters:

Here Philip prompts a series of speculative questions that guides this essay. How to hear these interminable calls that swell across the globe and resound from the depths of the Atlantic? If the present were to acknowledge these oceanic transmissions, then in what forms might we differentially enter into relation with them? And how to respond without disciplining these sounds into the epistemes of the present that are still constituted by unfreedom? That is, how to honour these sounds without yielding to self-gratifying narratives of liberal freedom that grasp Black life through colonial forms of being?

3 Part of the problem with which I am concerned in this article is how Philip’s lament imagines modes of being outside colonial ontologies. Zong! initiates a mode of thinking blackness beyond what Sylvia Wynter theorizes as the figure of Man. For Wynter, Man encompasses the present monopoly on the story of the human. “These systems and stories produce the lived and racialized categories of the rational and irrational, the selected and the dysselected,” Katherine McKittrick explicates, and thus “signal the processes through which the empirical and experiential lives of all humans are increasingly subordinated” (Wynter and McKittrick 10). The overrepresentation of Man as the governing genre of the human, a white liberal monohumanist figure of bio-economic universality, stands to recuperate these sounds and, in turn, reinstate the ban that Philip lifts by fading the court record, Gregson v. Gilbert, into a timbre of unremitting complaint.

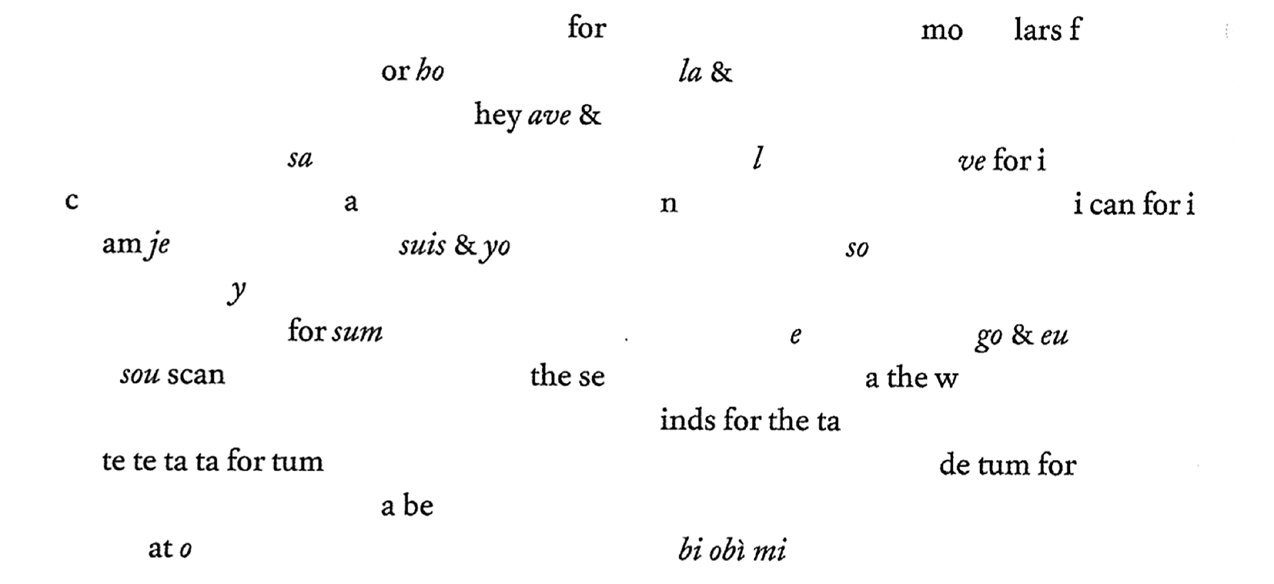

4 Philip touches on this issue early on in “Notanda” when she intimates that a discordant poetic can restore humanity to the African captives thrown overboard in the Zong Massacre. It is “through mutter, chant and babble,” Philip claims, that “the African, transformed into a thing by the law, is re-transformed, miraculously, back into human” (Zong! 196). Nonetheless, the category of the human with its footing in the coloniality of being is not neutral. As Eva Karpinski contends, “Zong! can be viewed as a philosophical and linguistic meditation on the meaning of humanness” (640). Given the intermittent wails and broken lines that mark the poem formally as a lament, what might it mean to read Zong! not as merely facilitating re-entry into a fixed genre of being but as remixing the category of the human?1 Consider, for example, the following sequence in Zong!

Here Philip assaults the grammars of being as they appear in the colonial tongues of English, French, Spanish, Latin, and Portuguese. The ontological sovereignties of “i am,” “je suis,” “yo soy,” “sum ego,” and “eu sou” are thrown into states of crisis by the poem’s deepening caesurae.

5 In these ruins of colonial being, Philip directs us elsewhere — the “sea” and the “winds” — to “scan” for a “beat.” In addition to recasting being as rhythmic and dynamic (“beat” is sonically altered as a broken “be / at”), Philip creates a sonic of life that raises the possibility of another sound of being human, which arises from within the crushed grammars of colonial being. We are invited to “scan” the water and the air to locate these “beats” of life. In one sense of the verb, a cursory “scan” of the page picks up the onomatopoeic, extralinguistic drumming that Philip sounds in plain sight: “te te ta ta for tum de tum.” In another sense, we could try to “scan” the poetry for a recognizable metre only to realize that versification comes up woefully short. Alternatively, we might hear “scan” through an auditory register: that is, to scan the sea and the winds for signals tuned to discrete frequencies, joining together two senses of the word wave: oceanic waves and sonic waves.2

6 Returning to the sequence above, at what frequency must we be attuned to sense these transmissions and beats of life? To ask this question is to situate Zong! as sound writing, a variation of what Alexander Weheliye calls “phonography,” which vacillates between the phono (voice and sound) and the graph (writing) (Phonographies 38). Despite being page bound, Zong! is sonic matter. These sound writings, however, are also rife with movement. With each broken line, the poem prompts lateral and horizontal motion through linguistic recombination. Consider how “move” itself can be formed by merging “molars” and “salve” in the above series. Nonetheless, this movement toward meaning restricts the sonorous to linguistic signification since it occludes the extralinguistic entanglements of sound and movement that squelch across each page. Put another way, the letters that scintillate across the pages of the poem generate choreographic sequences that deserve to be acknowledged as sonorous matter in their own right without allowing linguistic meaning solely to determine their relation.

7 In this regard, Zong! is not only a sound writing but also a sequence of sounds and movements that coincides with the sense of what Ashon Crawley calls the “choreosonic”: “[C]horeography and sonicity — movement and sound — are inextricably linked and have to be thought together” (28). The choreo bursts with sound. It pivots on and off the chorus. As Saidiya Hartman explains, “The Greek etymology of the word chorus refers to dance within an enclosure. What better articulates the long history of struggle, the ceaseless practice of black radicalism and refusal, the tumult and upheaval of open rebellion than the acts of collaboration and improvisation that unfold within the space of enclosure?” (Wayward 347-48). These songs and dances that unfold within the enclosure of Gregson v. Gilbert convey the immanent structure of Zong!, which sounds and moves Black life within the death world signed by the court report.

8 Gregson v. Gilbert is one of the few traces left of the Zong Massacre, making its flagrant disregard for the wilful murder of African captives during November and December 1781 all the more exasperating. Although there are many accounts of the massacre,3 the timeline might be constructed as follows. After months at sea because of navigational errors during a transatlantic voyage from West Africa to Jamaica, the slave ship Zong was amid an epidemic with an alleged lack of water. Guided by maritime insurance logic, the captain, a surgeon named Luke Collingwood, ordered his crew to throw African captives overboard in order to collect insurance on them. The insurance policies would be rendered void if the captives died “natural” deaths. Later, in Liverpool, Thomas Gilbert, the insurer, refused to compensate the Gregson Syndicate, the owners of the Zong. The case subsequently appeared before the English courts in 1783. In the first trial, the Gregson Syndicate successfully claimed that the act of murder — “jettisoning cargo” — was justifiable given “the perils of the seas” (Zong! 210). Gilbert still refused compensation. He called for an appeal, which took place at the Court of King’s Bench under Chief Justice Lord Mansfield. Although Mansfield ordered a new trial, it is unclear whether it ever happened. As such, the results are unknown. It is this appellate document, which considers the murder of Black humanity to be an insurance dispute over “cargo,” that becomes the “word store,” as Philip terms it (Zong! 191), for the composition of Zong! Despite the 1783 document’s hostility to life, Philip unexpectedly transforms this document of destruction into a site of unlikely generativity, which she fragments and recombines anew to materialize the lives of the African captives that the legal decision silences.

9 Yet the question with which I began this essay remains: how to enter into relation with these sound-movements, these choreosonographies, that infuse the water and the air? This question becomes all the more pressing when we note how these sound-movements are constituted by caesurae that incessantly interrupt the poem. How, in other words, to “scan” — to return to the language of the poem — absence? Critics, taking their lead from Philip, tend to read these broken passageways as spaces that mediate linguistic relation between the text’s fragmented words. Philip writes that “every word or word cluster is seeking a space directly above within which to fit itself and in so doing falls into relation with others either above, below, or laterally” (Zong! 203). Winfried Siemerling notes that “these silences are as relevant and as generative of meaning as the words on the page,” concluding that, “[s]ince this spatial poetics offers almost unlimited combinatory possibilities, meaning-making seems entirely contingent on each individual or collective act of reading” (237). Although Siemerling is certainly right, I want to add here another possibility.

10 By taking Philip’s assertion that the poem is “a sort of negative space, a space not so much of non-meaning as anti-meaning,” as our guiding quotation, might life emerge otherwise by reading these breaks as silent noises, aquatic and sonic waves, that are extralinguistically plentiful with sound and movement themselves (Zong! 201)? In place of signifying lack, generating meaning for the present, or standing as passageways to linguistic relation, what if we read the breaks in the poem as cries so vociferous that they sound on ultrasonic waves audible only at the ends of Wynter’s Man? Philip’s shape-shifting poetics and their persistent breaks would signal, then, a certain hesitation, in Lisa Lowe’s meaning of the word, that “halts the desire for recognition by the present social order and staves off the compulsion to make visible within current epistemological orthodoxy” (98). It is these typographical spaces of withholding, opacity, and hesitation that interest me here.4

11 I seek to acknowledge these negative spaces as sound-movements that vibrate on frequencies that cannot (yet) be adequately picked up from within a present governed by asymmetrically distributed unfreedoms. Without discounting the undeniable narrative threads of meaning in Zong! — such as the story of Wale and Sade and their child Ade — or denying the extralinguistic force of the songs, shouts, and cries legible in the poem, I want to direct critical energy to the stoppages that make possible the subjects, voices, stories, and meanings that do surface in the poem.5 This is the sonographic undercurrent of the poem, which can be imagined and sensed as a sonar that communicates as ultrasonic force to honour the African captives who are no longer, while refusing to make their lives intelligible within the epistemic categories of the present in the name of the not yet.

12 These opaque sounds and movements of life come to the fore when reading Zong! as a lament. Philip herself defines the poem thus: “My book-length poem Zong! is a lamentation” (Bla_k 298). Indeed, Zong! exhibits all of the tics of the form. Rebecca Saunders defines lament as “tonally unstable, and metrically interrupted by sobs, moans, or weeping, [and] its meanings are estranged in broken lines, peculiar phrasing, and shifts in stress” (73).6 The poem’s broken, shifting tenses and widening caesurae form a poetics that questions its own mode of delivery. Philip’s suspicion is largely of the English language, a “foreign anguish,” as Philip writes elsewhere (“Discourse” 58): that is, a central mechanism of colonialism. She explains her method of composition through a tactic of ruin: “I murder the text, literally cut it into pieces, castrating verbs, suffocating adjectives, murdering nouns” (Zong! 193). Her antagonism toward the English language generates, in turn, a politico-poetics in which language operates at its limit, fatigues intelligibility, and ultimately illustrates Rebecca Comay’s characterization of the lament’s philosophical mood: “a hypertrophic case of language [that] challenges language’s basic operating rules” (259). Read in this manner, Philip’s complaint against linguistic sense unsettles the disciplining grasp of coloniality on the present. Put otherwise, Philip twins grief and grievance in her “mutilation” of Gregson v. Gilbert to honour the African captives who are no longer, by materializing within the breakages of its grammars worlds that, as Weheliye writes, “can be imagined but not (yet) described” (Habeas Viscus 127).

13 Against this backdrop, these opaque sounds and movements materialize through the poem’s antithetical and antiphonal structure, integral — as Margaret Alexiou identifies in her seminal text on ritual lament — to the lament form. First, there is antiphony. Alexiou writes that “the origin of the lament [is] in the antiphonal singing of two groups of mourners, strangers and kinswomen, each singing a verse in turn and followed by a refrain sung in unison” (13). Saunders explains that “lamentations are often constructed by a soloist and chorus, the former leading or improvising, the latter echoing, revising, (dis)confirming” (63). The antiphonal structure of the lament is a communal and improvisational form of call and response that is often the unacknowledged labour of women. Second, there is antithesis. Antithesis, according to Alexiou, “is not a mere stylistic affectation, but is determined both by the antiphonal structure and by the underlying thought” (150). Reading Antigone, Alexiou lays out how the antiphonal dialogue between Antigone and Ismene is executed as each character expresses an antithetical thought by recasting one another’s words. Saunders provides a helpful gloss on how antithesis functions here: “[A]ntitheses frequently took stichomythic form — a dialogue in alternating and contrasting lines, which often involved an appropriation and reinterpretation of the interlocutor’s words” (62). In my reading, this antiphonal and antithetical structure assumes a textually immanent form in Zong!

14 Lament thus opens a formal loophole to acknowledge how these sound-movements, which undulate across each page and exceed description, are nonetheless made possible by, but are not reducible to, antithesis and antiphony. On its antithetical axis, Zong! places Gregson v. Gilbert in opposition to itself. By eviscerating the court report, Philip recombines its words to sound the silenced lives of the African captives who have always existed within the legal document. Philip affirms that “the Africans are in the text” (Zong! 192). On its antiphonal axis, Zong! engages in an immanent call and response with the silences made audible by the antithetical fold of the text. Philip answers the calls of the African captives present at the centre and surface, not at the margin, of the 1783 court record. As she says when discussing another work, “the ancestors become the call and we the response” (Bla_k 62). Philip thus choreographs a sequence of sound-movements that exceeds the violence of Gregson v. Gilbert from within, taking the position that, in her words, only in “impossibility” will there be any “potential for the possible” (“Interview” 138).

15 Although Zong! necessitates divergent readings, I emphasize the impossible possibility of Zong! as a material and extralinguistic affirmation of Black life that honours the worlds that always will have been sounding and moving with plenitude in the abrasions of Gregson v. Gilbert. The argument below unfolds in three parts, building upon the formal terms of lament explicated above: grief, grievance, antithesis, and antiphony. In the following section, I address the twinning of grief and grievance. In the penultimate section, I think through the antithetical registers of the poem, and then I conclude with a discussion of antiphony.

“question the now”

What can we do but grieve.

— M. NourbeSe Philip, Bla_k (20)

16 Upon first glance, Zong! labours to “question / therefore / the age,” as the poem pronounces in its opening pages (14). With this questioning, Philip stages a hearing, a retrial of sorts, that resounds Gregson v. Gilbert. This hearing tries the court of reason and its positive laws that ratified the wilful murder, the throwing overboard, of African captives. Grief is always already grievance, as it were. Although I take grief and grievance to be co-implicated and any attempt to dissociate them to be transitory, it is instructive here to parse them separately at the outset. At the one pole, there is grief, a plaint, as Philip says elsewhere, “for that which was irrevocably lost (language, religion, culture), and those for whom no one grieved” (Frontiers 56). At the other pole, there is grievance, a complaint, in the name of the not yet: that is, a complaint, most clearly, against the laws that sanctioned the African captives’ deaths and reduced their worlds to speculative capital through the maritime law of the general average and its attendant discourse of absolute necessity.7

17 The “not yet” is important because this impossible case of Zong! is not hermetically sealed within the eighteenth century. The poem is not a self-enclosed echo chamber of loss. Consider how the pronouncement “question therefore the age” is countersigned sixteen pages later by the utterance “question the now” (Zong! 30). These phrases demand to be read together. In order to sound this phrase, “question the now,” Philip inverts the following sentence of Gregson v. Gilbert: “It has been decided, whether wisely or unwisely is not now the question, that a portion of our fellow-creatures may become the subject of property” (Zong! 211; emphasis added). In her hands, there is a turning back of the syntax that puts off questioning chattel slavery, for “now the question” becomes “question the now.” Having broken the phrase out of its inessential function within the non-restrictive clause, Philip performs an anastrophic transposition that retracks Gregson v. Gilbert, forcing the question of slavery that once occupied a grammatical position of negation to sound in the present in reverse. Spinning the legal record back, the poem sends time backward — complicating simple recoveries and returns — to gather in the now as a question to, of, and for the present that is not (yet) free.

18 This palindromic movement agitates the question of slavery, torquing it from its hardened nominal form (now the question) to release an untrammelled verbal force (question the now) that makes its grievance audible in the positive (it is now the question) while, in the same stroke, expanding and collapsing the duration of the “now.” This questioning of the now processes the time of slavery as a series of antitheses: “this is / not was . . . this be / not” (Zong! 7). Within this non-synchronous now that is and is not, Philip constellates the transatlantic slave trade with differential geographies in the present such as the anti-Black, settler colonial state operative in Canada today. Lord Mansfield’s admission following the initial trial concerning the Zong case — “the case of slaves was the same as if horses had been thrown overboard” (Walvin 153) — is merely a different note in the same aria of anti-blackness heard in Brampton, Ontario, after the police carded and murdered an unarmed Black man named Jermaine Carby: “I remain satisfied on reasonable grounds that the subject officer acted lawfully in self-defence when he shot Mr. Carby and that there is therefore no basis to proceed with charges in this case” (Hudon). These “reasonable” grounds, and this four-hundred-year soliloquy of Black death, typify “the intensive policing of Black life in Canada,” as Robyn Maynard writes, that began “on slave ships and persists into the present, spanning the criminal justice, immigration, education, social service, and child welfare systems” (49). The hearing of Zong!, then, worries the temporal boundaries of the transatlantic slave trade and its afterlives, but it also lodges, by extension, a complaint against the very possibility of questioning itself. Taking its own inaudibility as one of its grievances, this impossible hearing sounds a grievance against the court that restrains its legibility through a narrative enclosure that is conditioned on and conditions Black death.

19 To “question the now,” at its root, is to raise an objection to the anti-Black epistemes that differentially govern the present. In this sense, Zong! is a hearing without a hearing, or a hearing of a hearing, that grates against the court’s legitimacy and evidentiary processes by assaulting the language of the law. Zong! arraigns to “clear the law / of / order” and “cause / delay / of question” (50). Philip’s obliteration of Gregson v. Gilbert empties the order of law by exacerbating and exposing its spectacular display of ordinary violence, which is only, as Philip says, “masquerading as order, logic, and rationality” (Zong! 197). By a similar token, if Gregson v. Gilbert delays the question of slavery within the structure of the law, then Zong! can be said to delay the very process of “questioning” itself by figuring the ground of questioning as yet another procedure of coloniality. The very tenses that give shape to questioning and hearing, the normative orders of the present, are contingent on the indispensable dispensability of blackness. As Philip writes, “the tense / is all / wrong” (Zong! 68). At its very limit, then, to “question the now” is recursively to place “questioning” under just as much duress as the verb question grammatically does to the noun now.

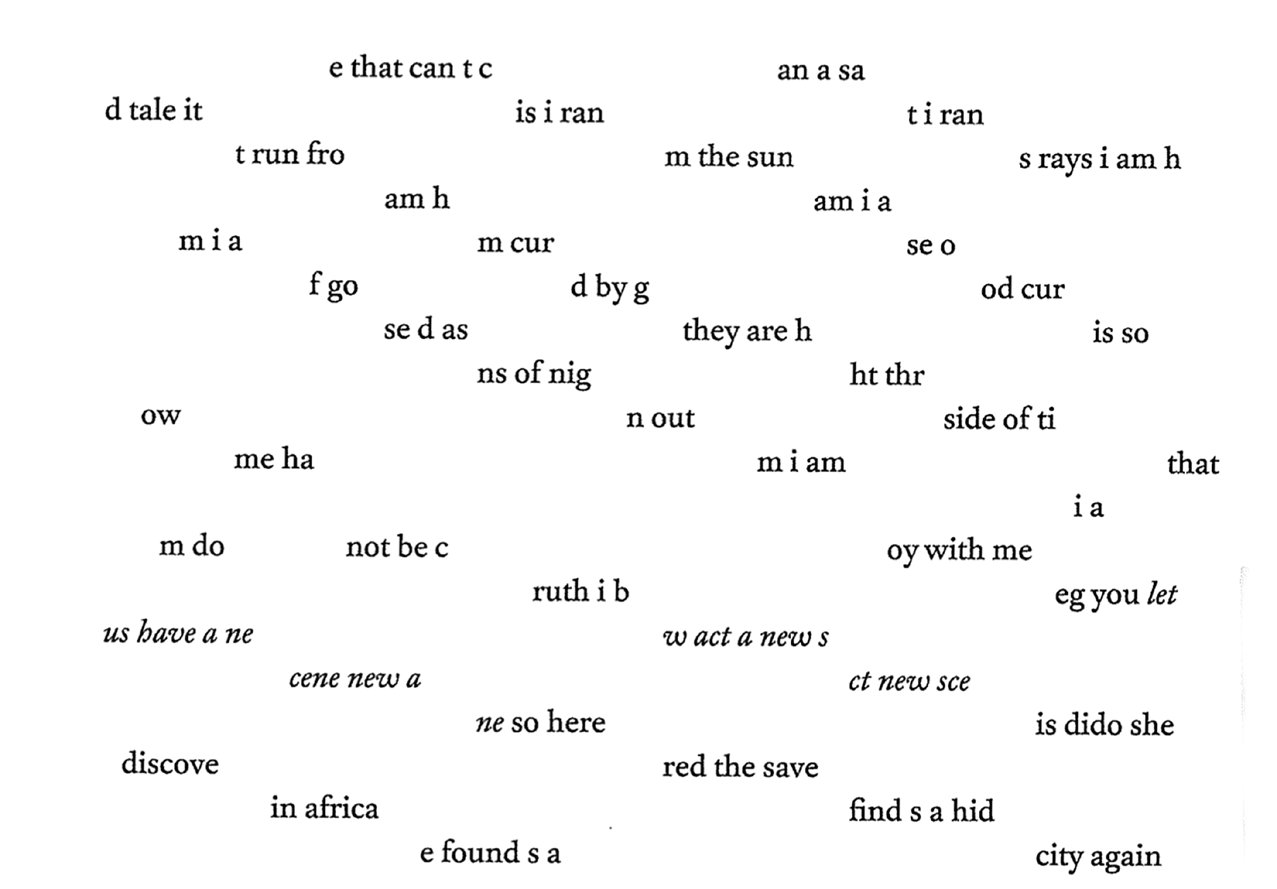

20 I want to suggest, then, that the poem’s temper of lament aesthetically facilitates this recursive questioning that is not comfortable in any tense.8 Zong! literally ruptures the building blocks of narrative by eviscerating language’s basic semantic units, illuminating the antithesis that informs Philip’s composition: “There is no telling this story; it must be told” (Zong! 189). From one angle, this antithesis speaks to the archival lack that vaporizes the Zong Massacre as an object of historical study. Not even the logbook survived the journey. From another angle, Philip’s poetics of un/telling align with what McKittrick describes as the analytic and narrative reprisal of anti-blackness: “a story that corresponds with our existing system of knowledge, one that has already posited blackness and a black sense of place as dead and dying” (16). The narrative grasping of the sounds and movements of the African captives thrown overboard for insurance money first arises in the abolitionist context of the late eighteenth century. In March 1783, Gustavus Vassa wrote to Granville Sharp with the murderous news that would soon spread outward from London. From this moment, “many Britons,” Vincent Brown observes, “told and retold the story, in the vocabulary of evangelical moral sentiment” (160). From there, a certain abolitionist rhetoric of theological and moral sentiment gripped the Zong Massacre as an icon of universal humanism, saturating the entire scene, as Ian Baucom writes, with “its own internal economy, an internal system of measuring, valuing, and distributing the social passions” (245).

21 Despite writing a few years before the Zong Massacre, John Wesley, the English cleric, in his pamphlet Thoughts upon Slavery, provides an arresting image, a metonym of the time, in his petition to God. He begs God to “Stir them [African captives] up to cry unto thee in the land of their captivity; and let their complaint come up before thee; let it enter into thy ears!” (57). Here God is asked to breathe complaint into the African captives so that he can listen to the very cries that he has blown into them. God, to put it another way, is imagined by Wesley as engaging in a tortured form of divine auto-affection. God listens to himself cry. In this self-enclosed auditorium of redemption, God enchants the bodies of the captives as if they are marionettes, possesses their voices, and moans sentiment through them, running his own voice back to himself in circuits of providential feeling. Black life is recouped and silenced by an echoing world of white feeling that grafts its own affective and theological economy onto the sobs, cries, and shouts of the African captives.

22 This narrative capture persists in the present. In 2007, a year before the publication of Zong!, a replica of the Zong sailed up the Thames to commemorate the event. Anita Rupprecht describes the boat as “a replica three-masted schooner built in the 1940s, used as a prop in the recent film Amazing Grace, now rechristened and escorted by the enormous, heavily armed, naval frigate, HMS Northumberland” (266). What is more, aboard the ship, “a mixed-race Christian choir sang hymns of thanksgiving, including John Newton’s ‘Amazing Grace’”; in “the hold of the replica ship, an exhibition told the story of slavery through text and image” (266). This celebratory assemblage of theological and national terror praises the nation’s efforts in its so-called triumph over slavery, which not only instrumentalizes the memory of the transatlantic slave trade by making it an emblem of national accomplishment but also cordons off the present from the past as if anti-Black racism has been succeeded by an era of post-racial harmony. These sounds of “freedom” reappear and intensify the thrift of moral sentiment that dogged eighteenth-century discourses of abolition. It is no surprise, then, that Wesley mentored Newton, a participant in and beneficiary of the transatlantic slave trade, as is well known. Despite the absence of a plea for God to eavesdrop on his own cries here, complaint is equally thwarted. In this contemporary exchange of African captives for a Christian choir, the sounds of complaint, what Hartman calls “black noise — the shrieks, the moans, the non-sense, and the opacity” are smoothed out (“Venus” 9), sweetened, into hymns that choke the air as the militarized force of the naval frigate patrols the waters. This scene could not diverge more from the aesthetic temper of Zong!, which refuses to massage language into a lyrically affecting sonority. There is no room for sentiment, identification, or empathy in its pages.

23 Philip’s fugitive and fugal operation snaps the units of linguistic sense, precluding these narratives from gathering. This hostility toward language distinguishes her poetic lament from other recombinant methods of revivifying life in the archives of slavery, such as Hartman’s “critical fabulation” as “recombinant narrative” (“Venus” 11). Significantly, Philip also uses the term “recombinant” to depict her approach to witnessing life in death; however, she gives it a negative bent as “recombinant antinarrative” (Zong! 204). I take one difference to be that, though both Philip and Hartman recombine death worlds as life worlds by generating poetic existences out of relative dearth, Philip materializes the abstractions of fabula, the constituting events of story, by asserting their presence in and through the materiality of language. Philip holds fast to the exact language, the sole remaining point of contact, that sanctioned the dehumanization of the African captives. Plainly put, she takes the kernels of life to be embedded within language itself.

24 For Philip, body is thus text, and text is body. As she writes in relation to Black women’s bodies, “In turn the Body African — dis place — ‘place’ and s/place of exploitation inscribes itself permanently on the European text. Not on the margins. But within the very body of the text where the silence exists” (Bla_k 270).9 Philip, far from lapsing into semiological reductionism, invites us to take seriously language as matter in its own right. She turns to the unlikely Gregson v. Gilbert to animate the presences of the African captives that dwell at the document’s centre. To explicate, there are silences within the words of Gregson v. Gilbert that become “Silence” when the legal document is “fragmented and mutilated” (Zong! 195). This is precisely why the interplay of grief and grievance is of note. Philip’s hostility toward the court record clears space to sound and move the presences that are inscribed on the surfaces of the document and are its legal and semantic sine qua non, which is “silence” in the colonial idioms but becomes “Silence” in Zong!

25 Each caesura opened up by Philip’s mutilation of linguistic sense sounds and moves as “Silent noise.” To write of Silent noise is to cross-fade her conception of Silence with Hartman and Stephen Best’s theorization of Black noise. “Silence” is a pivotal term for Philip and fundamental to her 1991 text, Looking for Livingstone: An Odyssey of Silence. She provides a helpful gloss on silence and Silence in “Notanda”: “[T]he metamorphosis occurs when the lower case ‘silence’ of the colonised becomes the fertile Silence of the Traveler” (Zong! 196). In Zong!, the silenced life of Gregson v. Gilbert becomes Silence when Philip responds to and releases it from “[w]ithin the boundaries established by the words and their meanings” (195). “I hunt the pieces of my silence,” writes Philip of her poetic process, “within the larger text of silence — words” (Bla_k 260). Her antagonism toward Gregson v. Gilbert, the grievance that “mutilates” the document, cranks up the timbres of silence to Silence, sounding and moving the presence of the African captives, the no longer, who stitch together and outstrip the legal record’s syntaxes.

26 This Silence, however, is also filled with Black noise, which Hartman and Best define as the oscillation of “grief and grievance,” plaint and complaint, that emits “political aspirations that are inaudible and illegible within the prevailing formulas of political rationality” (9). As the Traveller in Looking for Livingstone tells us, “And then I wove some more and came to understand how Silence could speak and be silent — how Silence could be filled with noise and also be still” (54). The Black noise that swells in each caesura channels the extralinguistic force of lament, for Black noise is “the extralinguistic mode . . . that exists outside the parameters of any strategy or plan for remedy” (Hartman and Best 3). In its inaudibility to the very “trap of reason” that it questions (Zong! 169), lament necessitates a hearing of the hearing that disciplines the worldings of the already and the not yet. Black noise underscores this mode of reading Zong! as a complaint that disrupts the narratives of Man from assembling, but also, more crucially, it acknowledges the opacity of the worlds that sound and move as Silence in the law’s grasp, opaquely forming a tapestry of “illegible yearnings” that are “wildly utopian and derelict to capitalism” (Hartman and Best 9). To say this another way, the grief and grievance that Zong! carries are not merely reactive to Gregson v. Gilbert. These sound-movements that persist in the long poem are not tethered to the law as reactionary matter; rather, their sonic materiality breathes, desires, thirsts, and imagines in ways that exceed the narrative enclosure of the legal document.

“why are we in this tale”

This has never happened to us before; this has always happened to us before.

— M. NourbeSe Philip, Bla_k (242)

27 The antithetical axis of Zong! hovers over Hartman’s problematic: “What of their existence can be exhumed from the archive: the ship’s manifest, the legal case, the newspaper profile, the death table, the actuarial chart, the autopsy report, the tally of police killings?” (“Dead” 208). Hart-man enunciates the pulse of an immanent poetic sensibility, which she calls “a poetics of the document” that can be traced back, at least in the context of contemporary poetic production in Canada (“Dead” 209), to Dionne Brand’s Primitive Offensive (1982), one of her earliest collections. Although not formally writing through another source, Brand’s speaker imagines herself as an “archaeologist” who sifts through the wreckage of colonial histories to locate “any evidence of me” (30). Instead of simply disavowing these colonial documents, Brand invokes the possibility of locating presence from within sites of absence. As Philip states, “Zong! reminds me that we can find our lost selves in the most unexpected of places” (Bla_k 341). It is this counterintuitive move to (re)inhabit epistemically violent sources to acknowledge the life that will have been always pulsing at the centre (and not the margin) that comprises the general antithetical tendency of Zong!

28 The poem’s antithetical structure is mirrored by its compositional principle. Philip frequently inserts this antithetical principle of the story that cannot be, but must be, told into the poem itself. For instance, she writes,

A stripped-back antithesis surfaces here in the pastoral ruin of biblical narrative: “can t / can.” Philip presents this antithesis amid the narrative debris of the story of Cain and Abel. This centralizes the mark and curse of Cain, the fugitive wanderer, often conflated with the curse of Ham in the policing of what Wynter terms the “dysselected.” On the next page, a voice cements this relation by announcing that “I am ham ham I am I am curse of god” (133). This is only one of the Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian narratives that Philip conjures up. To name but two of the most prominent, there is Circe and Dido. Both narratives serve as avatars for racializing logics. Although deserving of their own analyses, Circe metaphorizes the animalizing valences of slavery through her power to turn people into animals, whereas Dido, the wanderer, who also appears here (“did do”), motions the “discovery of Africa” trope through her “founding” of Carthage.

29 Philip could be dismissing these narratives as mere “cant,” but it is worth considering how she plays here on the homonymous slippage of “can” and “able.” The figure of Cain transforms into verbal (in)capacity: the line oscillates between removing and inserting the subject, the “i,” out of and into “Cain”: “cain can cain can.” Cain is transformed into the modal auxiliary verb “can,” then back into “Cain,” and then back into “can.” On the one hand, this erasure of the “i,” this ejection as abjection, registers the racializing declensions enacted by the curse of Cain that mark the dysselected and serve to rationalize the transatlantic slave trade. On the other hand, this effacement of the “i” lays bare a zone of potentiality: a “can” that emerges through the nowhere of the “i.” Philip rearranges Cain as can. The mark and curse of Cain slip into an odd potentiality.

30 The foregoing slippage brings us to what Christina Sharpe calls “anagrammatical blackness,” which takes the anagram as both a literal and a metaphorical way of thinking blackness as “an index of violability and also potentiality” (75). Here the indeterminacy afforded by being rendered violable is also a site of potentiality, a move related to what Darieck Scott terms “extravagant abjection”: “a black power that theorizes from, not against, the special intimacy of blackness with abjection” (259). With this tale, Cain flips to can through the denial of subjectivity (the subtraction of the i) that unleashes a zone of potentiality in which blackness is extravagant, “more and less than one in nothing,” as Fred Moten might say (774). If we read on, this can as unmitigated potentiality collides with the cannot — a cannot that can: “can t can.”

31 The anagrammatical meets in and as an analogue for the antithetical. The antithetical widens the frame to think the processual movement of the anagram in slow motion as it falls away and returns to itself anew: it makes audible the air that escapes as Silent noise in the turning over of the letters. “There’s the rub — you need the word — whore words,” Philip writes, “to weave your silence” (Looking 53). Returning to the passage above, we might acknowledge what we have been passing over: namely, the waves of suboceanic sound that will have been moving everywhere and nowhere across the page, “putting pressure on meaning and that against which meaning is made,” to quote Sharpe again (76). In the breakages of these letters, language is set against itself, turning itself out, extending the anagrammatical code, the life, latent within the letters of the text to leak into and fill the field around it. From this perspective, the Silence is even louder than the words that it holds apart and together: it is ultrasonic noise vibrating across the page that cannot (yet) be described in the grammars of the present. These breaks concretize extralinguistic relation in their uncoupling of the letters from their linguistic structures that they simultaneously suspend, support, and exceed. To scale back out and turn us over to the final section of this essay, this is where antithesis enmeshes with antiphony. The antithetical directive of the poem, which senses the silent calls trapped within Gregson v. Gilbert, smashes the text wide open, folds it against itself, and releases these sound-movements as responses of Silence that are everywhere and nowhere on the pages of Zong!

“can you not hear from the deeps”

One need not strain to hear the voice of our complaint still resounding.

— Saidiya Hartman, “The Time of Slavery” (775)

32 It is somewhat perplexing that antiphony as a formal aspect of Zong! has been neglected in the mounting scholarship on the poem cycle. Philip foresees this critical omission in an early interview with Kate Eichhorn: “With Zong! I suspect people will first see its experimental nature and its relationship to the modernist traditions, but in its use of competing motifs and stories, I see links with certain aspects of Yoruba aesthetic practices. I suspect it will take a longer time for readers to see that” (148). Although antiphony is not exclusive to the domain of Yoruba artistic expression,10 it is, as Philip states in an earlier essay, an “African art form. Together the call and the response make up the whole expression, or the expression of the whole” (Frontiers 70). Paul Gilroy, more broadly, situates antiphony in the Black diasporic context as “the principal formal feature” that is “a bridge from music into other modes of cultural expression, supplying, along with improvisation, montage, and dramaturgy, the hermeneutic keys to the full medley of black artistic practices” (78). To put the antiphonal relation of Zong! simply for the time being, the silence of Gregson v. Gilbert places the call, and the Silence of Zong! sounds the response.

33 It is admittedly both appealing and intuitive to read this relation as a combative response to Gregson v. Gilbert, an oppositional gesture of resistance to the document that grasps Black humanity as capital and cargo. From this vantage, Zong! is a response to and a rewriting of the 1783 document that fails to question transatlantic slavery and mass murder, a document that is a dispute over maritime insurance law instead of a murder trial. In this context, the question is whether or not Thomas Gilbert is obliged to pay insurance funds, thirty pounds sterling per African captive, to the Gregson Syndicate for Luke Collingwood’s putative decision to “begin jettisoning those likely to die in order to save the lives of the majority of those on board” (Webster 291). An entire mode of reading proceeds from this antiphonal agonism. The task? To analyze Zong! against the grain of Gregson v. Gilbert. This is an illuminating approach, to be sure, but this comparative stance (taken alone) occludes the generativity of the extralinguistic cessations that engulf each and every page of the poem, thereby misdirecting our attention from the call-and-response structure that occurs between silence and Silence. To repeat Philip’s comment when discussing “Discourse on the Logic of Language,” “the ancestors become the call and we the response” (Bla_k 62).

34 The antiphonal form that the poem effects does not respond to Gregson v. Gilbert in reactionary fashion; rather, the antiphonal relation is one of “first statement.” Philip describes “first statement” as the position of not “being determined by what I oppose” (Frontiers 64). In contradistinction to becoming a reactive force that obeys the terms set by Gregson v. Gilbert, Zong! responds to the calls of the African captives that sound and move through Gregson v. Gilbert but are barred from appearing. Yet this is not to position Philip’s politico-poetic as an ingenuous manoeuvre of historical excavation that recuperates marginality for the centre. It is, inversely, to query alongside Rinaldo Walcott, “What happens when marginality is not claimed but the centre is assumed instead?” (“Who” 39). To think of the antiphonal relation in Zong! as a call and response between Philip and the ancestral is, in her words, “to design imaginative and poetic scapes with us at the centre” (Frontiers 70). This principle of antiphonal first statement (and not reaction) is made most obvious by the poem’s double authorial signature. There is the call of the ancestral voice(s), Setaey Adamu Boateng, and there is the response of Marlene NourbeSe Philip. This framing of the text situates the poem by way of an antiphonal relationality, even though it is not as if these voices are clearly demarcated in the poetry itself.11

35 This is not to indicate that antiphony is necessarily limited to two discrete subjects, for antiphony, especially in the case of lament, involves at least one chorus with innumerable participants. To take a minor detour, the formal complexity of the call-and-response structure plays itself out when Philip performs Zong! collectively. She has performed the poem in a variety of contexts and capacities across the globe, such as the performance that she holds every November to commemorate the Zong Massacre. The performances tend to be durational, improvisatory, and participatory, often including dance and instrumentation. Philip writes that “we have a collective reading of the entire book. One of the remarkable observations is that although the content is tragic, at the end of the reading/performance there is a feeling of coming to rest, of peace, even. This confirms my belief in the capacity of art [to] heal” (Bla_k 341). These performances are lamentations, wakes, in which sonic collectives form not to give voice to the dead but to enact the singular, unique, and embodied processes of differentially attending to Black life. These performances produce a multitude of emergent, singular, and heterogeneous forms whose materialities cannot be anticipated in advance. Participating in these collectives is to respond differentially to the calls that Philip makes audible as she orchestrates sonic communities that hold open space together to honour the dead.12

36 I want to conclude by thinking about the material manifestations of these antiphonal rumblings that sound and move across the pages of Zong! It is my sense that this antiphonal Silence surpasses the pressure that Gilroy asserts antiphony places on subjectivity in his thinking of an “ethics of antiphony” as an “intersubjective resource” (200). The antiphonal Silence overtakes this intersubjective reserve and with it the subjective to accrue life asubjectively. The poem is thus more akin to what Crawley refers to as an “antiphonal collectivity” in which each breath and break “foregrounds the intensity of the pause, felt instantaneously, as absolute potentiality, absolute capacity” (50). This antiphonally Silent noisescape suffuses the entire poem. We can open virtually any page of the poem and sense these vibrations at varying speeds and intensities. Here is another page of Zong!:

This antiphonal collectivity respires in the cracks of Man’s shattered aria of a theocentric narrative, the curse of Ham and Dido’s “discovery” of Africa, both of which, as gestured to above, serve to differentiate the selected from the “dysselected.” These breaks in narrative surge forth with possibility and life in the nowhere of the sea. The intermittent breaks and folds, which “snap the spine of time” (Zong! 141), survive here and signal these cries and groans turning ultrasonic, sounding and moving beyond all legible forms intelligible in the present.

37 Each caesura thus advances Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s incitement to ask the question “How would you recognize the antiphonal accompaniment to gratuitous violence — the sound that can be heard as if it were in response to that violence, the sound that must be heard as that to which such violence responds? . . . [W]e don’t know what we mean by it, because it is neither a category for ontology nor for socio-phenomenological analysis” (95-96). The antiphonal collectivity that Zong! broadcasts can be heard as Silence, extralinguistic Black noise, that affirmatively responds to — and makes materially sensible — the silence that is the condition of possibility for the syntaxes of Gregson v. Gilbert. Here and nowhere, which is also a “now here,” the caesurae orchestrate a sociality of the hold that bla_ks out not only ontology (note the repeated splintering of the first-person singular present “am”) and socio-phenomenological analysis but also linguistic analysis. One hesitates to cohere these grammars of Silent noise that exhale before and beyond the semantic, exasperating any attempt to extract sense from the poem. Narrative repeatedly sputters here (the white sailor calls for a new scene), and every ambition of hermeneutic repair within the present is inevitably foiled by the yawning wounds that Philip punctures in the grammars of Gregson v. Gilbert that negatively record the “no longer” and the “not yet.”

38 This Silence is filled with derelict noise that is conceptually opaque to the present tense, holding open space not to demand the otherwise but already from within the otherwise that the present cannot (yet) meaningfully describe. The antiphonal relation here allows us to name the limits of analysis, an extralinguistic relationality of impossible possibility that can be imagined but not (yet) narrativized. This aesthetic strategy takes up once again Sharpe’s “anagrammatical blackness”: “blackness anew, blackness as a/temporal, in and out of place and time putting pressure on meaning and that against which meaning is made” (76). These fractures of life — as violability and potentiality — push the anagrammatical to its limit, sounding the presence of Black life in the hold as movements of Silent noise. These antiphonal ruptures that sound and move across each page not only rearrange and disturb the grammars of Gregson v. Gilbert contingent on Black life but also surpass the very grammars that seek to include Black life within the given tenses of the present. These sound-movements cannot be delimited through the where, the who, or the what, since their when, the future anterior, sounds a Silence that ignites everything, collectivizing a field of relation that is everywhere and nowhere, “an extra-phenomenological poetics of social life” in Moten’s words (756), an infinity and nothingness of intimacy and life within the hold.

39 The songs and cries of Zong! are sonorous plaints of extralinguistic plenitude that reside at the heart of Gregson v. Gilbert. These sounds and murmurs are not exterior to the insurance claim document, as I have been arguing, but the sounds that make possible and outstrip the discourses and world of Man. As Weheliye writes, “While this form of communication does not necessarily conform to the standard definition of linguistic utterance, to hear Aunt Hester’s howls or the Muselmann’s repetition merely as pre- or nonlanguage absolves the world of Man from any and all responsibility for bearing witness to the flesh” (Habeas Viscus 127). These sounds demand that one bear witness and acknowledge the life that teems within and through the document that Philip has released as Silence. Each break is “poetry from the future,” in Kara Keeling’s rendering of Karl Marx’s phrase, which upsets “narration and qualitative description” to sound “a felt presence of the unknowable, the content of which exceeds its expression and therefore points toward a different epistemological, if not ontological and empirical, regime” (567). The breaks, then, are the points in the text so full of sound that they break the barrier of what is available to thought in the present. They are sound-movements in excess of thought itself.

40 This is the power of reading Zong! as lament. The poem expresses grief (a plaint) for those who are “no longer” while also lodging a grievance (a complaint) irreducible to the anti-Black epistemes that govern the present from the “not yet.” Ultimately, this is to intimate that Zong! is ahead of us. The movements and sounds that comprise Zong!’s Silent cartographies of “a lower frequency,” in Gilroy’s terms (37), produce caesurae in the descriptive statements of the present. Philip formalizes this futurity in the material clearings that accumulate between the riven tenses and words of Gregson v. Gilbert, producing movements of extralinguistic relation that sound Silence as noise and grief as grievance. Here, in the anacoluthonic cut, the sequences of Man are unavailable for thought. By way of this incoherence of — and interruption of — thought, narrative stalls out in the infinity and nothingness of what Moten terms “no standpoint” (738). It is here that Zong! materializes a future, the end of the world, that will have always been sounding and moving within Gregson v. Gilbert.

Author’s Note

The section titles that appear in this essay are quotations from Zong! The quotations occur on the following pages, and I list them in the order of their respective appearance in this essay: 82, 30, 113, 152. I am grateful for the commentary and editorial suggestions on this essay by the two anonymous reviewers as well as by Cynthia Sugars. This essay also benefited from the additional comments of Ada Jaarsma, Billy Johnson, Devonne Garza, Henry Ivry, Ira Halpern, Kit Dobson, Lilika Kukiela, Max Karpinski, Rohan Ghatage, and Smaro Kamboureli. All errors are mine.