Article

Tekkietsertok’s Anger:

Colonial Violence, Post-Apocalypse, and the Inuit in Jeff Lemire’s Sweet Tooth Series

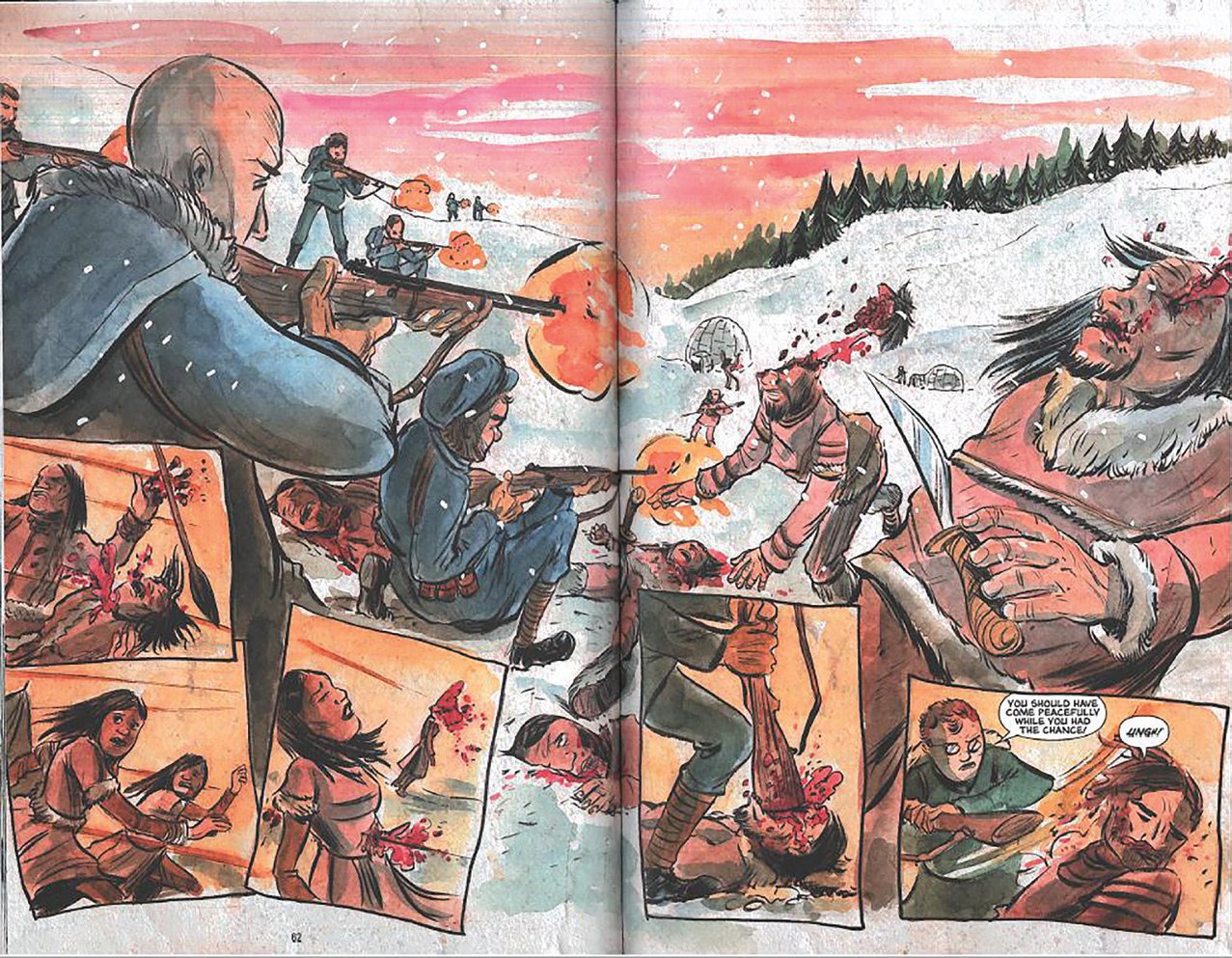

1 Two-thirds of the way through Jeff Lemire’s post-apocalyptic comic Sweet Tooth, readers are confronted with a visceral two-page spread detailing the massacre of an Inuit community by European explorers (Figure 1). Although Lemire does not shy away from violence in Sweet Tooth, the decision to use a two-page spread amplifies the horror of what unfolds and the cold brutality of James Thacker, a British doctor searching for Louis Simpson, his missing brother-in-law, and the European crew of the expedition. The violence is doubly emphasized by five inset panels that further illustrate the massacre without providing any text aside from Thacker’s ironic statement to his brother-in-law that he “should have come peacefully while [he] had the chance” (III: 63). Although these two pages represent a tiny fraction of the more than nine hundred pages of Lemire’s comic, they stand out visually as one of the most heinous acts of violence in a book full of violence, given that the narrative takes place after a virus has wiped out much of contemporary humanity and that life for the few survivors is all too often brutal.

2 This moment also stands out in the larger arc of Lemire’s narrative because it takes place at least a century before the cataclysm that nearly destroys humanity. Temporally speaking, the post-apocalyptic genre places itself in the near future, imagining the end of the world in order to warn readers in the historical present about some looming threat. What Sweet Tooth does differently is to argue that the violence that will threaten humanity’s survival in the coming years has already occurred in North America’s colonial past. Although Thacker is unaware of it, he and his men have become unwitting carriers of the apocalyptic plague. Simpson, a doctor turned Christian missionary, had unknowingly trespassed on a sacred burial site for the Inuit gods. An angakok, or Inuit shaman, explains to him that the tomb that he entered “was sacred to [the Inuit] . . . and never to be entered by anyone other than the shaman” and that Thacker had “angered [Tekkietsertok] and all the gods of this land and now there would be a price to pay” (III: 44). Sweet Tooth implies that the killer virus is Tekkietsertok’s revenge, fulfilling the post-apocalyptic genre’s convention of providing an identifiable cause for future disaster.

3 However, Lemire introduces a subtle twist by linking the imagined apocalypse with the devastation wrought on the Inuit peoples of Alaska by colonialism and introduced disease. Although Lemire does not connect his virus to an actual outbreak of smallpox or other introduced disease in Alaska, the timing of Dr. James Thacker’s journey to retrieve Simpson in 1911 places these events in the rough-and-tumble colonial period of pre-statehood Alaska, and the image of scarred corpses establishes a strong visual connection to the actual ravages of smallpox on Inuit bodies that happened in the early twentieth century (III: 21, 23, 68). Furthermore, the violence depicted above bears an uncanny resemblance to the ways in which colonial explorers often treated Indigenous peoples from 1492 onward. This juxtaposition raises a productive question: what happens when a genre predicated on imagined apocalypse connects to actual catastrophes for Indigenous peoples? Put differently, can a fictional calamity connect readers to the real history of catastrophic pain and loss that the Indigenous peoples of North America have lived through in the 528 years following European contact?

4 In what follows, I argue that Lemire modifies the typical chronotope of the genre, linking an imagined future with an actual past. Mikhail Bakhtin coined the term “chronotope” to refer to “the intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships that are artistically expressed in literature” and claimed that “it is precisely the chronotope that defines genre and generic distinctions” (84, 85). Whereas the chronotope of the western genre places narrative along the frontier between settlers and Indigenous peoples in North America in the late nineteenth century, the chronotope of the post-apocalyptic genre places narrative in an imagined future in which some form of wide-scale catastrophe has occurred. Yet these predicted futures are always meditations on the present circumstances of author and reader. In the fictional world of Sweet Tooth, there is no future for humanity since all humans die by the story’s end, but for readers the uncomfortable attention to colonial violence and the death and suffering caused by disease introduce another level of meaning that corresponds rather closely to the actual world. Although the series offers many of the usual pleasures of the genre, including what James Berger calls a “weird blend of disgust, moral fervour, and cynicism [that] helps [to] explain the enormous, ecstatic, fascinated pleasure many people in late 20th century America feel in seeing significant parts of their world destroyed — over and over” (7), it also calls on readers to witness the suffering of Indigenous lives at the hands of colonialism and to imagine a different future. This call to witnessing happens primarily through the repeated visual motif of characters who look out from their respective panels at the reader. In this productive visual strategy, Lemire moves away from simply offering an imagined end to a reader’s consumption and pushes the genre into social critique. In doing so, he joins a number of contemporary authors and comics artists who have taken up the post-apocalyptic genre and used it for critical ends.2 I argue that Sweet Tooth serves as an important step toward decolonizing the post-apocalyptic genre by utilizing this transgressive temporal structure that pairs an imagined future with the lived experiences of Indigenous peoples. Given the success of Sweet Tooth as a series and Lemire’s popularity as a writer, this narrative marks an important step forward in decolonizing the post-apocalyptic genre even if the final imagined future might not provide a clear way forward for readers in the present.

Introduced Disease as Apocalypse

5 "Although many post-apocalyptic texts use a virus or bacterial strain as their apocalyptic instrument, Sweet Tooth’s use of a virus in connection with the Inuit evokes the actual catastrophic consequences of introduced disease in the Americas following European contact. Historian James W. Daschuk writes that “the importance of introduced infectious disease cannot be overstated in the history of Indigenous America” (xii). Robert Fortuine goes further in his provocative claim that

the changes that these diseases brought about in traditional Indian life were probably of far greater importance than all the trade goods together. European diseases such as typhus, yellow fever, diptheria, influenza, and smallpox killed large numbers of native Americans who lacked a history of exposure and natural immunity, often decimating tribes by as much as fifty to ninety percent. (xi)

Although the encounters with specific diseases varied greatly across the different Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the cumulative effect of introduced infectious disease was enormous.3 Perhaps unintentionally, the blistered and desiccated corpses of the European explorers in Sweet Tooth bear a striking resemblance to the symptoms found on victims of smallpox (III: 21, 23, 68-69), one of the deadliest introduced diseases for Indigenous peoples. Environmental historian Alfred Crosby explains that “the impact of smallpox on the indigenes of Australia and the Americas was more deadly, more bewildering, more devastating than we, who live in a world from which the smallpox virus has been scientifically exterminated, can ever fully realize” (207). But it was not just the deaths directly attributed to the disease that were the source of such chaos. As Daschuk explains,

mortality from initial infections of smallpox has been estimated to be as high as 70 percent or more. Survivors can be sick and debilitated for long periods. Under these circumstances, food procurement strategies break down since there is often no one with the physical ability to hunt or collect food. Those with the dubious good fortune of living through the initial sickness can slowly die from hunger. (12)

After surveying the history of disease among Indigenous peoples on the North American plains, Daschuk writes that, “by 1740, disease was the primary factor in the wholesale redistribution of aboriginal populations of western Canada” (26). His measured language as a historian does not quite capture the vast changes caused by disease for all human life on the plains even as his book offers copious details on the many different epidemics that swept across the region. In this light, the results of the introduction of diseases such as smallpox and yellow fever among the Indigenous peoples of the Americas seem to be more like post-apocalyptic fiction than actual history.

6 I do not refer to these traumatic biomedical historical events lightly. They continue to live on in various forms as Indigenous peoples continue to suffer from the long-term consequences of violent colonialism across North America. Introduced diseases opened the door for the later conquest and subjugation of Indigenous peoples by European settlers, and Indigenous peoples continue to suffer from very poor health outcomes compared with non-Indigenous citizens of Canada and the United States. A recent health study of Inuit populations in North America makes it clear that disease continues to be deeply problematic as they face much higher mortality rates from tuberculosis, higher rates of chronic heart disease, and much higher risks from “the so-called social pathologies: violence, accidents, suicide, and alcohol and substance abuse” (Bjerregaard et al. 391). Furthermore, I am nervous about calling these events apocalyptic because the genre itself has emerged out of Western conceptions of end times, and there is a long history of Western epistemology consistently colonizing and appropriating Indigenous knowledges. However, I want to pose these actual catastrophes for many Indigenous peoples as a visceral and conceptual counterpoint to the fictional apocalypse imagined in Lemire’s Sweet Tooth series. I believe that this juxtaposition opens up a productive ethical space to work toward unsettling persistent settler myths that underlie not just this one apocalyptic narrative but also the apocalyptic genre as a whole.4 Still, there is an uncomfortable tension in doing so since the apocalyptic genre recalls colonial fantasies of dying Indigenous races that face their “logical end” because of “superior” civilization and conveniently die off so that the elect few can take up the “new” world and build a new utopia. Moreover, Lemire, as a critically and commercially successful white settler comics writer and artist who takes up ideas about Indigenous peoples and makes them key parts of his apocalyptic text, risks raising questions of appropriation and exploitation.

7 Nonetheless, Indigenous writers across North America have recently taken up the genre in fascinating ways. In an interview, Anishinaabe writer Waubgeshig Rice describes being inspired by Cormac McCarthy’s The Road because “it left me wishing for more stories like it from an Indigenous perspective. I felt that because Indigenous nations have already endured apocalypse and largely exist in relative dystopia, a book about the end of the world that’s centred on an Indigenous community would reflect a different spirit” (para. 3). Rice directly connects the historical and contemporary experiences of colonialism for Indigenous peoples to imagined apocalyptic futures. Similarly, in reflecting on writing her post-apocalyptic novel The Marrow Thieves, Métis writer Cherie Dimaline says that “I was telling [the] story from inside an apocalypse. And I could do this with absolute certainty in its viability because as Indigenous people, we have already survived the apocalypse. I was writing [a] dystopian future based on a dystopian past” (para. 3). This anchoring of the post-apocalyptic genre in historical events while framing the land and traditional Indigenous practices as the hope for future survival is also broadly visible in other contemporary Indigenous fiction, such as Richard Van Camp’s “Wheetago War” short stories, Thomas King’s novel The Back of the Turtle, and Louise Erdrich’s novel The Future Home of the Living God. Recent Indigenous comics such as Chelsea Vowel’s “kitaskînaw 2350,” Michael Yahgulanaas’s Carpe Fin, and Cole Pauls’s Dakwäkãda Warriors also adopt elements of this generic transformation to explore the complex relationship between colonialism and Indigenous peoples in a genre that scholar Roslyn Weaver points out often “conveniently rejects the past as irrelevant, a strategy that suppresses other (Indigenous) versions of history” (100). Yet Weaver observes that the genre is productive because “the apocalyptic paradigm of revelation and disaster can work effectively to interrogate the history of colonization and relations between white and Indigenous Australians, and propose spaces of hope for the future” (100).5 These Indigenous works all attest to the post-apocalyptic genre’s potential ability to imagine a different future as a part of present efforts at decolonization.

8 Yet these Indigenous visions of the future compete with those of non-Indigenous writers and artists who often command much larger audiences, so it is important to begin the work of decolonizing popular works that might trade in problematic colonial discourses.6 Lemire is likely Canada’s most successful contemporary comics writer and artist from both a popular and a critical perspective. The success of Essex County, a gritty and spare graphic novel about rural Ontario and hockey, opened industry doors for him to write scripts for some of Marvel and DC’s most popular series, and Lemire has been prolific for various other publishers. His Descender series, with Dustin Nguyen providing the artwork, drew such a buzz that Sony optioned the script for a film before the first issue was released. More relevant was the massive success that accompanied Secret Path, a 2016 multimedia work co-authored with Gord Downie, telling the story of Chanie Wenjack, an Anishinaabe boy who froze to death while trying to escape from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora in 1966.7 Sweet Tooth, published between 2008 and 2013, marks a crucial transition for Lemire from self-publishing his first work, Lost Dogs, for the small independent comics market in 2005 to signing an exclusive contract with DC in 2010, giving him access to the much larger American market. It also marks a key moment of his interest in Indigenous cultures. In an interview with Damon Lindelof, Lemire stated that, “Obviously, I did the Thacker story and the stuff at the end, but I’ve been reading a lot of Native American or First Nations literature and I think a lot of that has been seeping into my work, the second half of Sweet Tooth especially. Really a lot of that stuff comes from the idea of returning to nature” (para. 25). Given the success of the series and its importance to Lemire’s career, Sweet Tooth warrants a careful analysis of how it engages with genre, representation, and Indigenous history.

The Work of Genre

9 The argument that I am proposing depends on seeing Sweet Tooth as a representative example of the post-apocalyptic genre as a whole. It is in many ways a conventional example of the genre, featuring a cataclysmic virus that wipes out most of humanity and a narrative that focuses on a small cast of human survivors and Gus, a hybrid animal-human child. One of the prominent side effects of the virus is that humans now give birth to hybrid animal-human children. In an interview with Ben Peirce, Lemire jokingly described the series as “Mad Max meets Bambi” (55:35). Literary theorist Tzvetan Todorov argues that “it is because genres exist as an institution that they function as ‘horizons of expectation’ for readers, and as ‘models of writing’ for authors” (163). The dust jacket of Book One of Sweet Tooth describes the narrative as “a haunting tale of survival in post-apocalyptic America,” and the first few pages of the narrative recount “the accident” and the “fire and hell” that lie outside the Edenic sanctuary in which Gus grows up (I: 11). Visually, the appearance of crooked telephone poles and loose power lines on the next page informs readers that the world is broken, and the appearance of bloodthirsty hunters eager to kill a child by the end of the first issue further emphasizes the fallen nature of this fictional world (I: 12, 24-28). The first issue of Sweet Tooth presents readers with a clear “horizon of expectations” about the kind of world that they will encounter. The post-apocalyptic genre has conventional plot components and a number of key tropes that Sweet Tooth provides: the world has experienced a catastrophic incident, and civilization has collapsed; this collapse has created a state of permanent crisis for survivors in which survival trumps all moral considerations; there are numerous scenes of widespread devastation and ruin; there are nostalgic glimpses of the world that was lost; and violence becomes a significant, even primary, feature of any survivor’s life.

10 Although plot elements and motifs are important to any given genre, genres also encode particular cultural discourses about larger social and philosophical questions. John Frow argues that “genres create effects of reality and truth, authority and plausibility, which are central to the different ways the world is understood in the writing of history or of philosophy or of science, or in painting, or in everyday talk” (2). So, for instance, the genre of the western, from which Sweet Tooth borrows, structures the world in such a way that European civilization will inevitably triumph over the “savage” Indians in the wilderness frontier of America. Fredric Jameson offers a Marxist reading of genre in The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act, in which he argues that it is possible to read a generic text as “a socially symbolic act, as the ideological — but formal and immanent — response to a historical dilemma” (139). In that case, the western genre arises in direct relation to the actual decline of the American west as farmers and settlers complete the colonization of Indigenous lands. Similarly, the post-apocalyptic genre creates effects of reality and truth that are worth unpacking in some detail.

11 At the heart of the post-apocalyptic genre lies a social critique of the world as it currently exists. Berger argues that “apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic representations serve varied psychological and political purposes. Most prevalently, they put forward a total critique of any existing social order” (7). This claim holds equally true for religious apocalypses such as in the biblical Book of Revelation and a Hollywood blockbuster such as The Day after Tomorrow.8 What is lost in most post-apocalyptic narratives is any sense of a larger human community, whether regional, national, or global. In Sweet Tooth, though various characters do refer to widespread efforts to cure the virus, the narrative tends to be relentlessly local. This is in no small part because of the total collapse of global travel and communication systems. Across many contemporary post-apocalyptic texts, Sweet Tooth included, is a view that contemporary technology has caused humanity to lose sight of some fundamental aspect of what it means to live. Faced with the collapse of technological modernity, characters must rediscover what it means to be human.

12 A second underlying feature of the post-apocalyptic genre is the sense that the end will offer some revelation about a reader’s current situation. Frank Kermode, in his influential study of apocalypse, argues that “men in the middest [sic] make considerable imaginative investments in coherent patterns which, by the provision of an end, make possible a satisfying consonance with the origins and with the middle” (17). Kermode makes an analogy between apocalyptic visions and literary plots whereby readers trust that the end of a given fictional narrative will justify and align all of the previous parts. The post-apocalyptic text serves a pedagogical function for its readers, then, offering some vision or glimpse of how the world is working for those caught in medias res. However, as several other literary scholars have pointed out, this faith in a teleological view of history was decisively shattered in the twentieth century. Teresa Heffernan exemplifies this when she states that “apocalypse as the story of renewal and redemption is displaced by the post-apocalypse, where the catastrophe has happened but there is no resurrection, no revelation. Bereft of the idea of the end as direction, truth, and foundation, we have reached the end of the end” (11). Thus, there is a mutation in the genre whereby the initial meaning of apocalypse as revelation comes into question and might even be cancelled. This is evident in a work such as McCarthy’s The Road, in which any hope for the future is tenuous at best, with the bulk of the novel depicting the brutal cannibalistic violence to which humans have resorted after the end. Sweet Tooth’s own revelation is decidedly ambiguous: humans survive in the form of the human-animal hybrids born after the outbreak, but the cause of the end already happened a century ago, suggesting that catastrophe is inevitable.

13 The unique chronotope of Sweet Tooth introduces a tension between this particular narrative and the genre as a whole. Most post-apocalyptic narratives follow a chronotope whereby they are set in a near future in which an unimaginable catastrophe has happened or will happen shortly. The narrative continues forward from this first imagined end toward the text’s literal end. Kermode points out that apocalyptic thinking forces time to “bear the weight of our anxieties and hopes” (11). In this sense, the imagined future of a post-apocalyptic narrative reflects the reader’s present moment. So, for instance, at the height of the Cold War, many post-apocalyptic narratives such as Nevil Shute’s On the Beach used a nuclear apocalypse as their imagined end, whereas more recent texts such as Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake use anthropogenic climate change as the disaster. Where Sweet Tooth differs is that, rather than just being a forward-looking narrative, it extends its temporal scope backward to incorporate the catastrophes of introduced disease among Indigenous peoples in North America. The sudden convergence of the actual past with the imagined future of the narrative produces a strange doubling of perspective for readers as they realize that they are now looking both forward and backward in time. However, this unique feature does not cancel out Sweet Tooth’s exemplary generic nature. As Todorov points out, “the fact that a work ‘disobeys’ its genre does not make the latter nonexistent; it is tempting to say that quite the contrary is true. . . . [T]he norm becomes visible — lives — only by its transgressions” (160). Lemire’s decision to create an intertextual link to past catastrophes transgresses the normally future-oriented nature of the genre. Sweet Tooth therefore suggests that, for Indigenous peoples, the apocalypse has already happened; the world has ended yet somehow continues. And this transgressive move is a productive one since it might subtly shift the genre away from its dependence on the blunt mechanism of destroying the world in order to make it anew.

14 Finally, Sweet Tooth might help readers to rethink the colonial encounter between settlers and Indigenous peoples. Potawatomi scholar Kyle Powys-Whyte helpfully illustrates this idea when he writes about how his friend Lee Sprague reminds him

that [the] Anishinaabek already inhabit what our ancestors would have understood as a dystopian future. Indeed, settler colonial campaigns in the Great Lakes region have already depleted, degraded, or irreversibly damaged the ecosystems, plants, and animals that our ancestors had local living relationships with for hundreds of years and that are the material anchors of our contemporary customs, stories, and ceremonies. (207)

Sprague echoes Rice and Dimaline in pointing out that, from a certain standpoint, many Indigenous peoples already inhabit a post-apocalyptic world even as their continuing survival and more recent flourishing emphasize that the end was not the end. Indeed, settler colonialism depends on a clearing away of previous inhabitants of a “new” land in order that a “new” world can begin. In some sense, settler colonialism is a post-apocalyptic political order. To build Canada and the United States, various means were used to clear away existing communities. By using the destruction of an Inuit community as a synecdoche for colonization as a whole, Sweet Tooth makes visible the destruction and erasure at the heart of the colonial project in North America. And in doing so it might push readers to imagine a different present in which future violence can be avoided by the reconciliation of past violence.

Sweet Tooth and Indigenous Apocalypse

15 Sweet Tooth offers plenty of evidence that invites reading it as an engagement with colonialism in North America. In its first issue, two human hunters corner Gus, with one saying, “He’s ignorant . . . savage,” to which the other replies, “can’t be too savage . . . got clothes on, don’t he?” (I: 27). These casual references to savagery and ignorance echo settler colonial accounts of Indigenous peoples as noble savages or ignorant primitives. Later, Jeppard, the anti-hero of the series, will refer to Gus and his fellow hybrids as “little half-animal kids,” repeating another colonial stereotype of Indigenous peoples as animals or subhumans (I: 39). At the heart of these racist stereotypes is a desire to dehumanize Indigenous peoples and thus justify the dispossession of their lands. Furthermore, throughout the narrative, the hybrid children are treated as aberrant beings who must be confined to medical labs or eliminated outright. The “safe place” that Jeppard brings Gus to proves to be a laboratory where hybrid children are subjected to brutal medical experimentation. This plot turn calls to mind German concentration camps and the work of Josef Mengele, but it might also point to the medical testing done on Indigenous peoples in residential schools and sanatoriums in Canada, often without their consent or knowledge.9 At times, the narrative also evokes the western genre with gunfights, horses, and a kind of frontier justice in which might makes right. Jeppard himself can be read as a Clint Eastwood type: a well-armed loner figure dealing with internal grief and anxiety whose moral persuasion is ambiguous from the outset, while the hybrids are the Indian antagonists. However, Katherine Kelp-Stebbins points out that Sweet Tooth visually complicates ideas of self/other and hero/villain through “Gus’s hybridity[, which] engenders multiple perspectives, both from the top-down as the protagonist and son of men, and from the ground up as an animalistic other” (345). Although the “otherness” of Gus might seem to fit easily into a colonial binary of civilized colonizer/wild savage, Lemire consistently represents the hybrid children as relatively innocent and almost always the victims of human violence. Put together, this evidence offers some justification for reading Sweet Tooth as an extended allegory of colonial violence against Indigenous peoples.

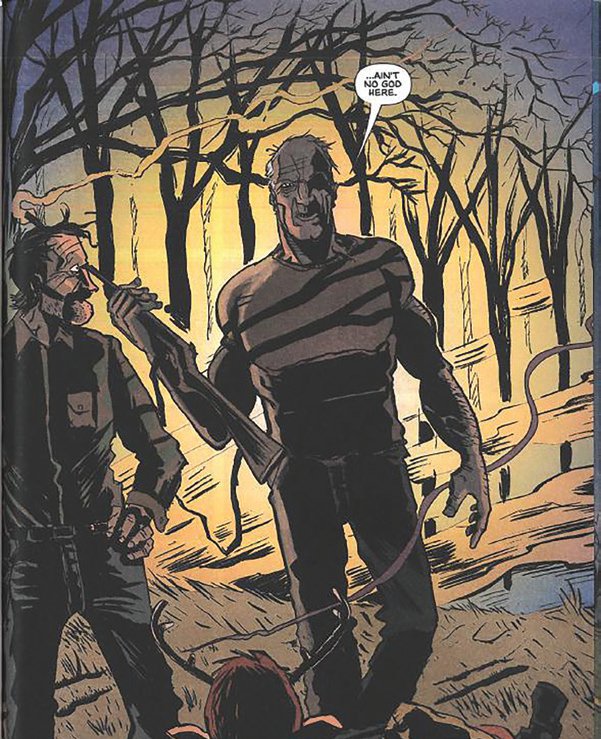

16 Furthermore, when the narrative shifts to Alaska, the Inuit become important figures in the plot. When Dr. Singh, the chief scientist for the primary antagonist and warlord Abbott, realizes that the outbreak likely began at a military base in Anchor Bay, Alaska (II: 83), all of the major characters begin to journey north. Although there are mysterious hints of Gus’s connection to an Inuit cosmology when a bear sees Gus as an Inuit god in the wilderness (II: 191), the first direct evidence of his connection to the Inuit happens later in issue 24. After Gus has been shot, he falls into a trance-like state and follows a skeletal deer guide to a beach with a beached sailing ship and, farther on, finds the remains of massacred Inuit villagers (Figure 2). This scene turns out to be a flashback to the destruction of an Inuit village by Thacker and his colonial explorers discussed above. However, the initial encounter with the Inuit peoples remains shrouded in mystery, and Lemire’s colour palette of brown, orange, and red watercolours and the strange figures, including a demon avatar of Abbott, prevent readers from recognizing the dream as foreshadowing.

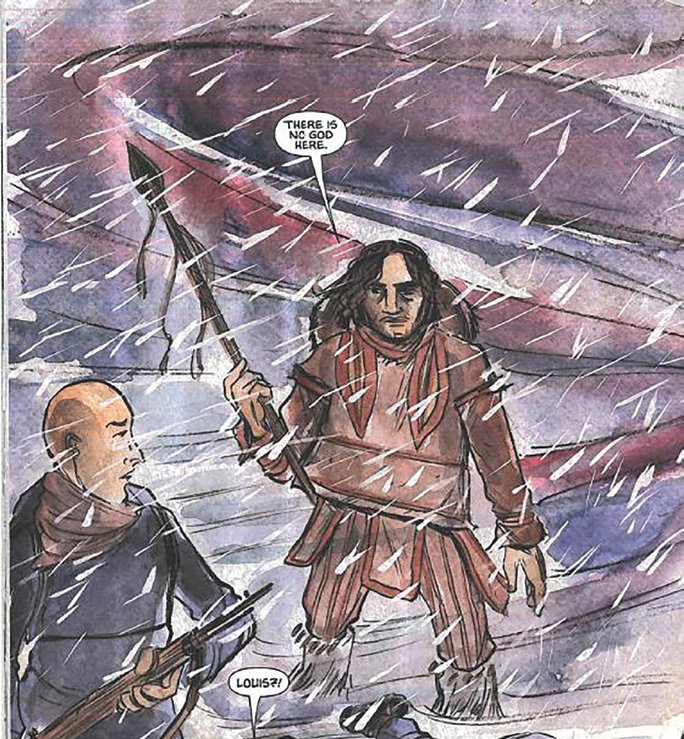

17 The truth is revealed in full two issues later when the narrative provides an explanation of the dream. Matt Kindt, an American comics artist, took over the artwork for three issues to allow Lemire time for other projects, and this resulted in a distinct visual difference between Kindt’s work and Lemire’s work. Kindt’s way of drawing the human body differs such that readers are reminded that they are seeing a new artist’s work. However, this visual difference is fitting as the narrative abruptly moves backward from the future to 1911. The first inset caption of issue 28 reads “the personal journal of Dr. James Thacker, September 4, 1911” (III: 7). This narrative flashback and difference in artistic style place added interpretive weight on this section. Kindt includes an ominous sign of a disastrous encounter between the Inuit and European explorers in the shape of a church full of diseased corpses (III: 21). Thacker and his men then encounter Louis, now garbed in Inuit clothing, as he declares that “there is no god here” (Figure 4). This panel provides an uncanny repetition of Sweet Tooth’s first issue, in which Jeppard announces his own presence with a declaration of “ain’t no god here” (Figure 3). The linguistic echo is matched by a visual rhyme in which the two pages are near copies of each other. Despite being 575 pages distant, the effect is dramatically to suture the historical Alaskan sequence to the imagined future of Gus and Jeppard.10

18 Louis’s dramatic entrance is followed by the revelation of the origins of the apocalyptic plague. Louis, who has “gone native” by marrying an Inuit woman and fathering a child with her, explains how he unknowingly trespassed on a tomb, “the home of Tekkietsertok . . . [t]he God of the earth who owned all the deer. He is the God of hunting. He is also the protector of any creatures that enter parts of the northern sky” (III: 44). In another uncanny narrative doubling, Louis sees a skeleton in the tomb that features a deer head and a human body, while his own newborn child is a boy-deer hybrid like Gus. Thacker is disgusted with Louis’s child, calling it “a freak, an aberration of nature! He is carrying the disease! If we kill it, the sickness will go with it” (III: 52), before murdering it. In the imagined future, Dr. Singh discovers that Gus is the first child hybrid, having no parents but being the creation of an American military lab. Louis’s child and Gus both resemble Tekkietsertok and are immune to the ravages of the virus. This implies that the virus is Tekkietsertok’s anger and that the children are spared because they are more creature than human. Both Singh and Thacker misattribute the disease to the birth of the hybrids rather than the human desecration of sacred space, establishing another uncanny repetition between historical past and imagined future. Thacker leaves Louis and the Inuit only to return with all of his men and perpetrate the massacre that Gus foresees earlier, just like humans in the future who use similar excessive violence in response to the virus and the hybrid children.

19 Regarding the two-page spread discussed at the beginning (Figure 1), Kindt and Lemire chose to put great rhetorical weight on this key moment of violence. In any comic, the choice to use a single panel across two pages immediately assigns that panel heightened significance. The two-page spread is the largest possible unit that a comics creator can utilize while still allowing the reader to take in the totality of images in a single gaze. Consequently, the rhetorical effect of a two-page spread is greatly amplified. This particular image is brutally effective in displaying a horrific act of colonial violence against the Inuit. The lack of text in dialogue or caption format affords readers no distraction from the slaughter. Throughout Sweet Tooth, Lemire and his co-creators use eleven different two-page spreads at key moments so that readers have their normal reading rhythm disrupted at various points by these large images. The effect is often to stop the reader’s forward progress through the narrative and keep attention on the image itself. Furthermore, the lack of a frame for this particular two-page panel creates a bleed effect whereby the image itself seems to expand beyond the literal pages of the comic. It “bleeds” off the text in a visceral way. This two-page spread is particularly difficult to look at because of the graphic violence displayed. As a result, it also offers a potent suggestion that this act of early colonial violence seeps beyond its moment to infect all that comes after it in the narrative. Moreover, the issue depicting this atrocity is titled “Apocalypse,” signalling how Lemire and Kindt want readers to interpret the violence. Pushed further, the apocalyptic violence of humanity as it goes extinct is simply a replaying of the earlier colonial violence against the Inuit.

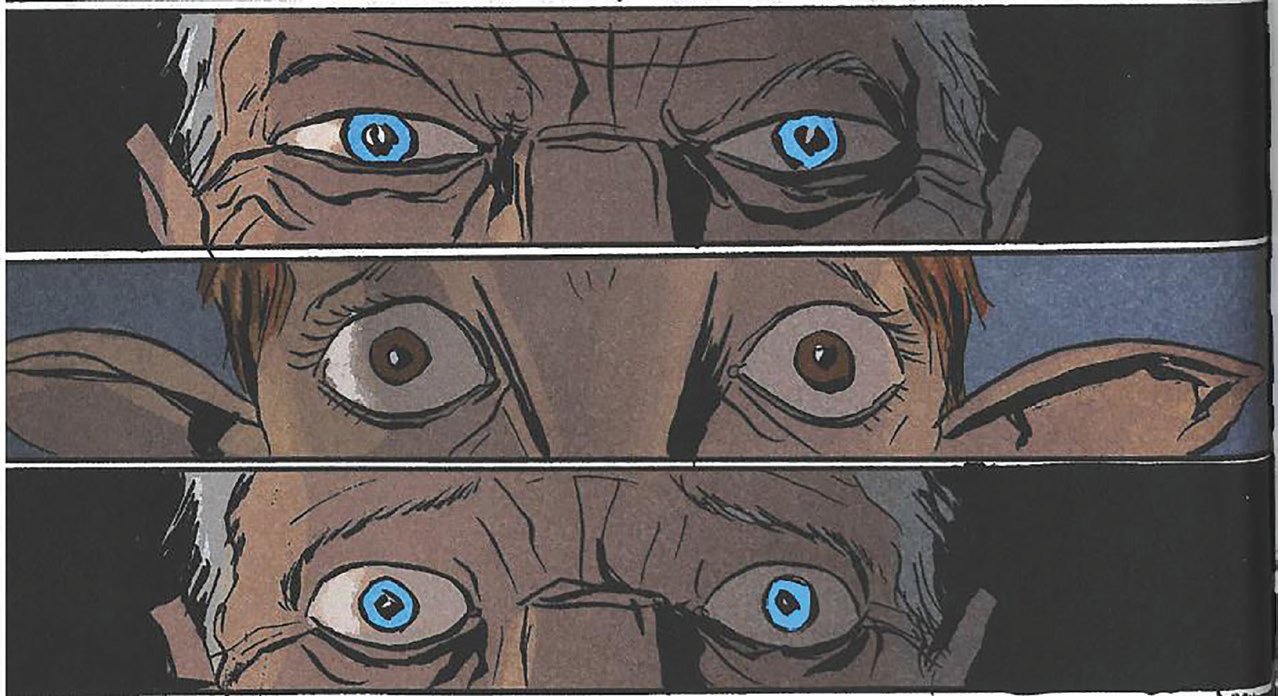

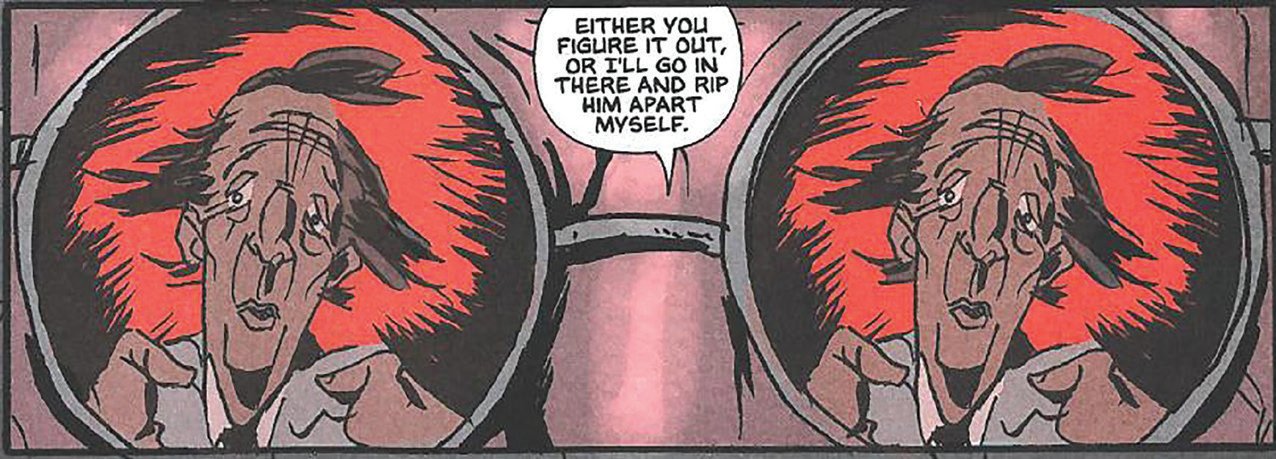

20 Furthermore, through the use of braiding, Sweet Tooth calls readers to witness this violence and its consequences. Translators of Belgian comics theorist Thierry Groensteen use the English word braiding for the French word tressage to refer to the ways that a “succession of continuous or discontinuous images [can be] linked by a system of iconic, plastic, or semantic correspondences” (System 146). The mirror images of Jeppard and Louis are a small example of braiding as it visually connects the two men through a similar pose and panel layout, reinforcing the ambiguity of both men as their arrival brings violence on those around them even if they seem like saviours. However, Groensteen argues that braiding is “a supplementary, contingent procedure, which is never necessary to the structuring and intelligibility of the narrative — at least at a first level of meaning that is perfectly satisfactory in itself” (“Art” 93). Readers can easily miss the visual and linguistic connection between Jeppard and Louis, but those who catch it experience the richness embedded in the comic. A far more obvious use of braiding is the consistent repetition of a page-wide horizontal panel that contains an extreme close-up of a character’s face, centring on his or her eyes. In the 928 pages of the series, Lemire and his co-artists use this kind of panel or a close analogue at least ninety-nine times (Figure 5). In this example, Jeppard encounters Gus for the first time, and the initial hardened look of suspicion and wariness shifts to one of empathy after he meets Gus’s wide and innocent eyes. André Cabral de Almeida Cardoso argues that Lemire uses the eyes as a “mechanism of sympathetic identification through the gaze” (para. 19). On a narrative level, Gus and Jeppard are looking at each other. On a visual level, readers are given alternating point-of-view shots, placing them in Gus’s and Jeppard’s bodies — we see what they see. But there is a secondary effect whereby Jeppard and Gus seem to be looking directly out of the page at the reader. These panels invite sympathetic identification with the characters, but they also unsettle the reader.

21 Lemire constructs a semiotic code with this repeated visual motif and uses it to tell readers how to interpret characters. For instance, when a character’s face is shown in extreme close-up, but one eye is closed, readers are alerted to that character’s suspicious motivations. In the first issue, Jeppard’s face is depicted three times in this iconic way (I: 8, 19, 28). On a primal level, readers distrust Jeppard because they cannot see his eyes clearly, and this fits since his motives for “rescuing” Gus remain unclear throughout the first third of the narrative. As readers discover, Jeppard betrays Gus by trading him to Abbott for the corpse of Jeppard’s now-dead wife. Significantly, when Gus cries out for Jeppard to help him right after the trade-off, Jeppard’s face is shown in the iconic manner, but his eyes are now fully closed (I: 121). In closing his eyes, Jeppard refuses to meet Gus’s supplicatory gaze and seems to close himself off from the reader. Lemire repeats these veiled or shadowed eyes with Dr. Singh and Haggarty (II: 244; III: 114), the former a scientist who kidnaps Gus and the latter a sexual predator and serial killer.

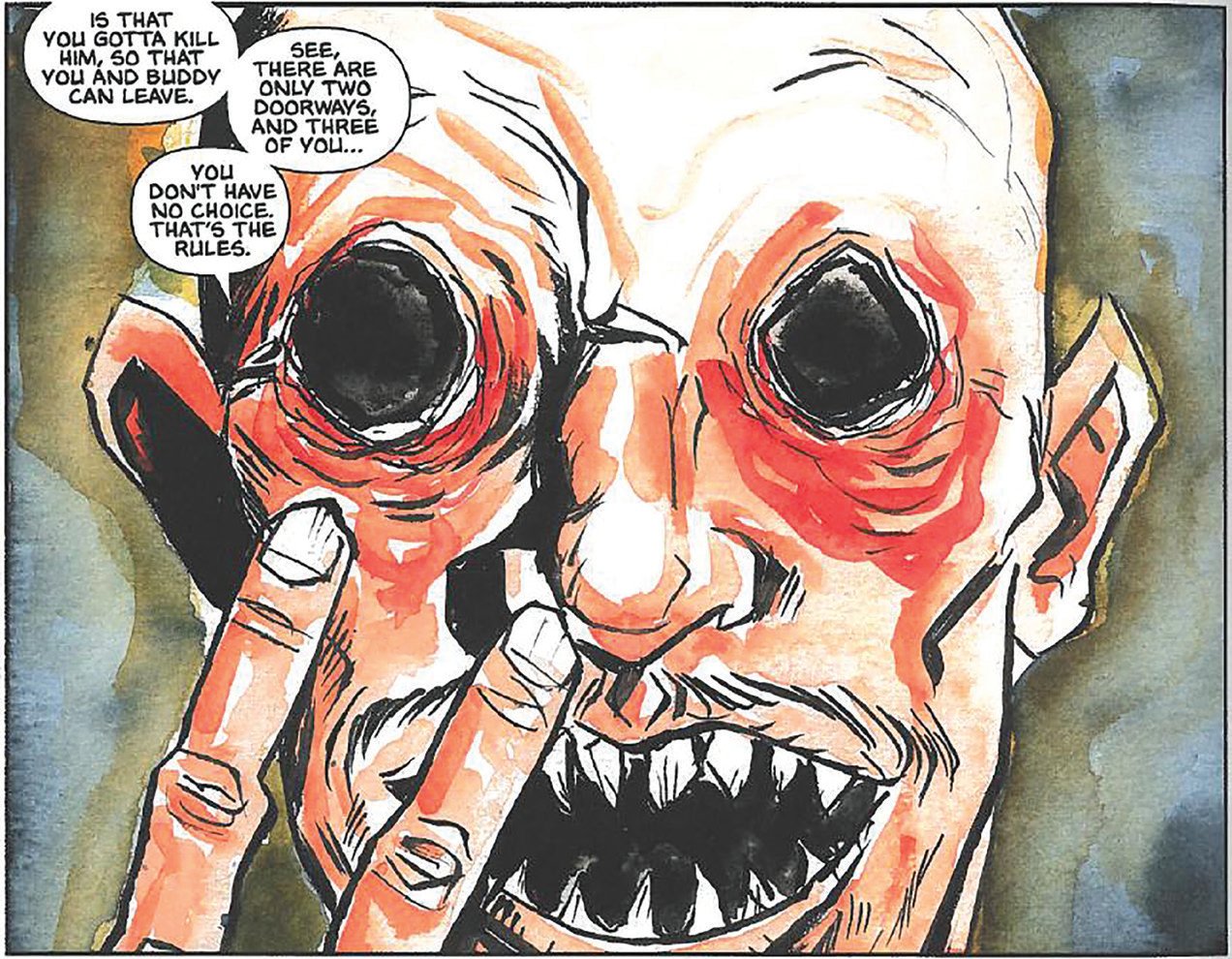

22 However, perhaps the most significant use of the eyes motif comes in the narrative’s primary antagonist, Abbott. Throughout the series, Abbott is depicted as wearing reflective black sunglasses that block any perception of his eyes. Not only can readers and characters not see his eyes, but his sunglasses often reflect back the monstrous deeds that he is committing. In the example below (Figure 6), Lemire’s image both hides Abbott’s eyes and reveals his assault of Dr. Singh. In a flashback to Abbott’s childhood, artist Nate Powell, who provided pencils and ink for this section, cleverly makes the teenaged Abbott’s glasses transparent until the moment that Abbott reveals that he has murdered his abusive father. At this point, the glasses become reflective and show reds and yellows in an ominous fashion (III: 189). By refusing to provide readers with access to Abbott’s eyes, Lemire limits a reader’s ability to empathize with this character. In some sense, Lemire dehumanizes Abbott. Moreover, when Abbott does take his sunglasses off in one of Gus’s dream sequences, readers see that he has no eyes at all but only empty sockets (Figure 7).These black pits and the mouth of shark-like teeth turn Abbott into a horror movie monster or nightmare creature. Given that Lemire consistently shows both human and hybrid eyes, his decision to refuse Abbott eyes visually marks the character as an incarnation of inhumanity or evil. It is not the plague that is the most terrifying but the seemingly bottomless pits of evil of which Abbott is capable. In this sense, he himself acts as a kind of allegorical figure for the colonial enterprise as he uses both broken promises and violence to seek his end. Pushed further, this panel turns Abbott into a visual metonym for the violent and cannibalistic core of colonialism itself: it is a system that feeds on new lands and the bodies of human and animal alike.

23 Moreover, the narrative arc of Sweet Tooth shows that the violence of Abbott and colonialism ultimately eats itself as he and the rest of humanity die from the plague just like Thacker and his crew did a century earlier. At the end of the narrative, the only survivors are the human-animal hybrids who make peace with the now infertile human survivors and allow them to die peacefully of disease or old age. Lemire reveals this complete destruction of humanity only in the final issue of the series, and in doing so he breaks from most post-apocalyptic narratives as humanity does meet its final end. Read as a social critique, Sweet Tooth suggests that the “historical” encounter of one group of Inuit with colonialism and disease in 1911 is the direct cause of the apocalyptic end for all humanity in the future. In a strange repetition of the historical settlement of North America, introduced disease again causes catastrophic damage, only this time it kills all humans. Pushed further, the return of disease functions ironically to produce a “new world” in a kind of historical justice granted to Sweet Tooth’s Indigenous/hybrid children.

24 Returning to the motif of eyes and the unsettling gaze, I note that the braiding of eyes discussed above performs a further interpretive function: it calls readers to witness atrocity. As Cardoso writes, “What these eyes see is a sustained spectacle of suffering. Mangled and bloody bodies, as well as bodies riddled by disease, are often displayed in Sweet Tooth, forming tableaux that are given a prominent position on the page” (para. 12). Although the violence in this particular imagined future might seem to be imaginary, the depictions of the massacred Inuit and the missionaries dead from disease bring the series uncomfortably close to the actual historical apocalypses faced by Indigenous peoples. Historians Alan D. McMillan and Eldon Yellowhorn describe the impact of the arrival of European whalers in coastal Alaska in the late nineteenth century:

[W]halers liberally dispensed alcohol, debauched Inuit women and brought diseases that nearly destroyed the Inuit communities. . . . Famine frequently followed outbreaks of disease, as there were too few able-bodied hunters to provide food. . . . Neither the shamans’ curing techniques nor the newcomers’ medical knowledge could halt the drastic population decline across the Arctic. (289)

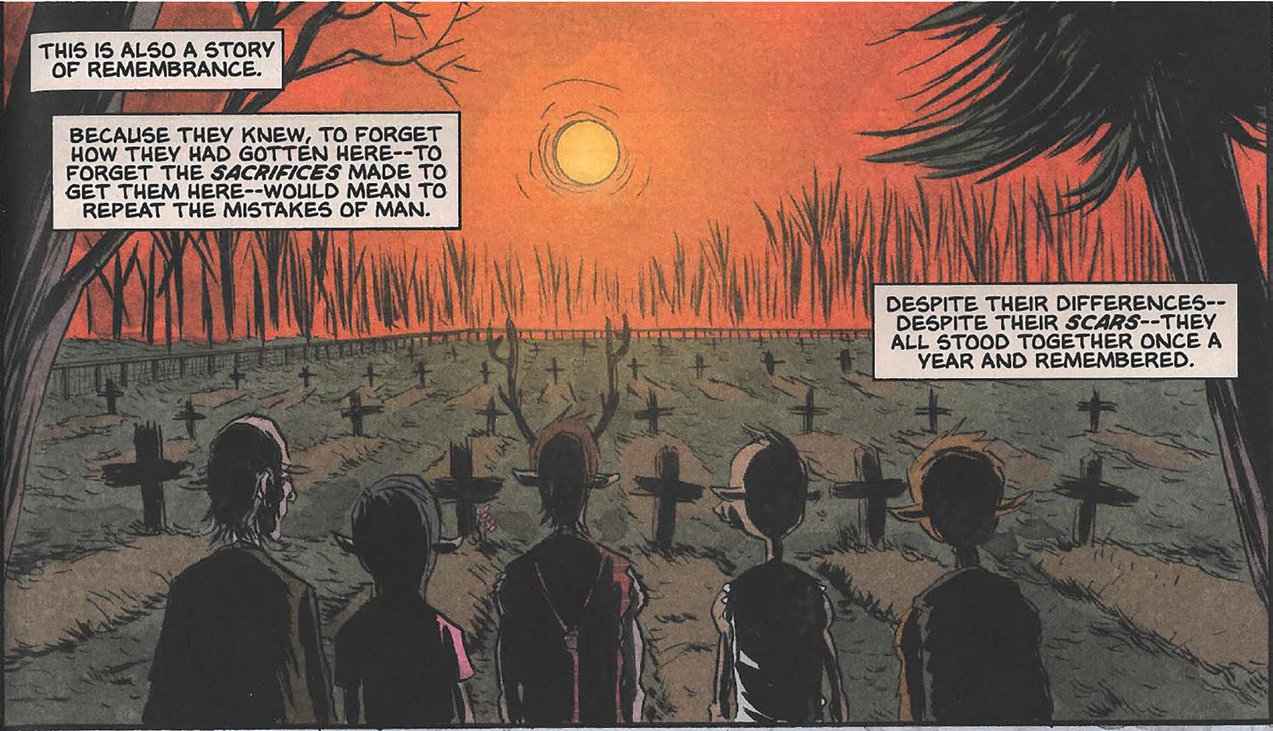

Moreover, witnessing the violence of humans against their animal others suggests how colonial forces treated Indigenous peoples as less than human. Lemire invites readers to see how the genre of the post-apocalypse uncomfortably repeats the actual historical catastrophes faced by Indigenous peoples. I argue that the repeated depiction of eyes staring out from the pages works to unsettle and invite closer scrutiny of what is on the page. Connected to Sweet Tooth’s ending, the narrative implies that the brutal originary violence of settler colonialism is the cause of the future end of our world. Yet witnessing might lead to a different future as the hybrids gather annually to remember the humans in order to avoid “repeat[ing] the mistakes of man” (III: 341; Figure 8). Pushed further, the inclusion of the Alaska/Inuit flashback might force readers to witness historical colonial violence against Indigenous peoples in the hope of not repeating those past mistakes in the present.

25 Lemire even offers a seemingly hopeful future in the final issue since the imagined future is a distinctly Indigenous one. Gus offers thanks to the gods before eating and leaves a part of the rabbit as “an offering back to the land that sustains us” (III: 322). In the new hybrid settlement, a carved totem pole occupies a prominent place, and Wendy has made bannock and stew for lunch (III: 330, 332). The new community uses a tribal council (III: 336). Furthermore, the members live in harmony with all species, even the dying humans who initially tried to kill them. Their new life is land based, as Gus makes clear: “[W]e took to the land. And it embraced us” (III: 325). A new chapter of life has begun, and this way of life is free from violence and hatred. Indeed, even the colour palette of the final issue, marked by faded browns, greens, and blues, sets the issue apart visually from what has come before. All told, this new community seems to be a utopia for the hybrids given what they have lived through.

26 As powerful as this reading might be, Sweet Tooth’s ability to offer a social critique for contemporary readers seems to be somewhat limited. On a narrative level, Sweet Tooth repeats a colonial trope in that one “race” must die out in order for another “race” to take possession of a new world. Read literally, the future will be harmonious only if all humans pass away because they are inherently prone to violence. Sweet Tooth might even suggest the inevitability of this process as colonial violence becomes a delayed terminal virus in this series. Perhaps by following the way of life of the hybrids, readers can become like them, telling a new story about them and avoiding such an end. The final issue gestures in this direction by thirty-one repetitions of the phrase “this is a story.” However, what is troubling is the fact that, as Weaver points out above, there is a radical rewriting of history here: all humans are held responsible for violence to the Indigenous other and animal life, and they all must die. This includes the Inuit, whose lives are ended not by any choice of their own but by the arrival of Simpson and the Europeans. Returning to Jameson’s view of generic texts as socially symbolic acts, this is a troubling move since it suggests equal fault on all sides. This rewriting erases the asymmetrical nature of the colonial exchange in North America. I do not mean to imply that Indigenous peoples were without violence — and neither does Lemire, for the hybrids do fight a partial war against human survivors — but that the cumulative effects of colonialism in Canada end with the mass dispossession of Indigenous lands and resources, numerous attempts to shatter Indigenous cultures, and continued subjugation of Indigenous lives through policy and policing. Sweet Tooth might call readers to witness colonial violence, but it also announces the end of the victims of that violence. If, as Anishinaabe scholar Lawrence W. Gross writes, “Native Americans have seen the end of their respective worlds . . . [yet] survived the apocalypse” in the historical world (33), in Sweet Tooth there is no such future survival. All humans become extinct. Lemire does not literally mean that all humans must become extinct before harmony can be achieved, yet his narrative leans toward this oversimplification.

27 Moreover, by keeping the events of first contact between the Inuit and British fictional rather than historical, Lemire asks readers to make the connection between fictional and actual worlds. Sweet Tooth has reached a wide audience in Canada and the United States; however, if that reading audience has no knowledge of the complex history of Indigenous-settler relations, then the transgressive parallel between a fictional catastrophe in Alaska and the historical catastrophes suffered by Indigenous peoples might remain unnoticed. Similarly, the vision of a good life in the final issue seems to be more of the no place of Thomas More’s Latin neologism utopia than something achievable in a reader’s present moment. Perhaps this is a fault line in the genre itself, in which the connection between an imagined world and a reader’s reality always depends on the reader’s interpretation.

28 A more productive decolonizing strategy would be to anchor the apocalypse in historical events as Indigenous writers and artists do when they take up the genre. Doing so both affirms Indigenous survival in the face of the violence of colonialism and offers readers direct connections between imagined futures and the historical past. Vowel’s “kitaskînaw 2350” offers an instructive example as it anchors a vision of the future in the practices and traditions of the Cree peoples, positing a solution to a catastrophic future in Cree knowledge. To be sure, Sweet Tooth offers a potent critique of the violence of colonialism; it calls readers to witness the settler tendency toward violence when faced with the other. It suggests a transgressive kinship of beings across species lines, as Kelp-Stebbins argues (339-40). Its final issue also self-reflexively points out that the post-apocalyptic genre is a story that might be retold according to different purposes. Although the vision that it presents falls short of a full decolonization, Sweet Tooth, as a best-selling mainstream series, pushes the post-apocalyptic genre toward a self-reflexive reckoning with North America’s colonial history and ongoing injustices.

Author’s Note

Thank you to the two anonymous reviewers and Tania Aguila-Way who provided helpful feedback to improve this essay. The members of the Association for Literature, Environment, and Culture in Canada heard the first version of this essay at a conference and offered encouragement and critique in equal measure, so I owe them a debt of gratitude as well. Thanks to Jeff Lemire for the permission to reproduce images from Sweet Tooth.