Articles

Toward a Feminist Archival Ethics of Accountability:

Researching with the Aritha van Herk Fonds

1 When I presented the paper from which this essay emerged at the Resurfacing: Women Writing across Canada in the 1970s/Refaire surface: Écrivaines canadiennes des années 1970 conference at Mount Allison University in April 2018, I felt nervous. In the preamble, I explained that I had drafted previous versions of the paper but felt uneasy and conflicted while writing it. I was conflicted because I was surprised at my strong desire to present a rigorous account of my archival research over two consecutive summers in Calgary. I wanted to be taken seriously as a junior scholar, but at the same time the feminist in me vehemently rejected the myth of the disembodied scholar distancing herself from her affective entanglement with the papers of the disembodied writer. I did not want to conceal the fact that Aritha van Herk’s writing had been a source of immense joy and excitement in my personal and professional lives for over a decade. I respect and admire greatly van Herk for her strength, her imagination, and her humour.

2 In this essay, I want to begin to think through a feminist archival ethics of accountability while working with the archival material of a living woman writer. In doing so, I consider my positionality during the joyful encounters with the archival material, some of the affective challenges that arise when working on/with a living writer, and how an empathetic archival practice can generate intergenerational feminist alliances. In the first part of this essay, I trace the efforts in feminist archival studies to engage more thoroughly with feminist ethical praxes that accommodate the stories of different bodies intersecting in the archival space. In the second part, I consider the Aritha van Herk fonds and draw on her novels Judith (1978) and The Tent Peg (1981). By putting each in conversation with reviews and reactions from the time of publication, I aim to demonstrate how engaging with archival material from the 1970s makes possible an affirmative recontextualization of the fonds within a contemporary feminist framework. Finally, I reflect on my positionality in the archive and my ethical accountability during the research process.

A Feminist Archival Ethics of Accountability

3 Since the 1990s, there has been a steady interest in archives as a theoretical concept and site of inquiry. What is generally termed the “archival turn” in the humanities and social sciences refers to archives less as passive repositories of information and more as sites of power relations in order to understand “the archive as a metaphor or as a discursive system” (Cifor and Wood 14). More specifically, within Western feminist studies, this focus on the archive has tended to be on the material that pertains to the history and representation of women’s lives rather than on applying a feminist praxis and ethics to archival research.1 Although it has become more common for researchers to engage with the wider power structures that can be found within and around archives, and to offer reflective accounts of their archival practices, Marika Cifor and Stacey Wood contend that “archival theory and practice have yet to fully engage with a feminist praxis that is aimed at more than attaining better representation of women in archives” (1). This is doubtless an important effort aiming to counteract centuries of women’s erasure from public records since the “visibility of female citizens is dependent upon the preservation of their socio-political and cultural traces” (Morra, Unarrested Archives 3).

4 Kate Eichhorn’s important The Archival Turn in Feminism: Outrage in Order (2013) presents one such effort not only to pay attention to the contents of archival collections but also to interrogate her affective entanglements with those collections, considering the archives’ myriad possibilities allowing feminists to be “in time differently, . . . temporally dispersed across different eras and generations” (x). Eichhorn views her work as a continuation of Ann Cvetkovich’s seminal An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (2003), though she thinks that “much has changed since [its] publication” (155). Eichhorn carefully traces the archive as a site of intergenerational conflict and contestation since, she claims, it is there that

Eichhorn further references Susan Faludi’s infamous Harper’s Magazine article on feminism’s self-inflicted death drive that Faludi claims is fuelled by a matricidal impulse, a contention that Eichhorn vehemently pushes against in her study, highlighting that even through disagreement she has “remained fiercely protective of what [the second wavers] represent and grateful for everything they have made possible in [her] personal and professional life” (27). I find wonderfully productive her focus on “being in time and history differently” (8), reading the archive as a “site and practice integral to knowledge making [and] cultural production” (3), as well as highlighting an archive’s potential to function as a bridge between different generations of feminists. Ultimately, Eichhorn states, archives are “shoring up a younger generation’s legacy and honoring elders [and] imagining and working to build possible worlds in the present and for the future” (x). This is particularly pertinent to the archival study of living women writers with whom the researcher can imagine past, present, and future worlds in creating feminist intergenerational alliances.

5 My suggestion for a feminist archival ethics of accountability is strongly influenced by the work of Michelle Caswell and Marika Cifor, who reimagine the archive and those implicated in its workings from a feminist ethics approach through the lens of radical empathy. Moving away from the model of the disembodied researcher, the authors propose the application of radical empathy as a new way of engaging with archival material. They view radical empathy “at its most simplistic [as the ability] to imagine our body in the place of another” and as a “learned process of direct and deep connection between the self and another [by] thinking and feeling into [the] minds of others” (30). Ultimately, Caswell and Cifor configure a feminist approach of radical empathy as “a willingness to be affected, to be shaped by another’s experience, without blurring the lines between the self and the other” (31). Their application of an archival ethics of empathy presents a framework that accounts for the lived and embodied experience since in “archives this attention to the body marks a new strain of inquiry” (31). The conceptual reintroduction of the body in the archive marks an important shift in how researchers have engaged with their own corporeality in archival settings.

6 An important intervention in the field is a special issue of Archival Science titled Affect and the Archive, Archives and Their Affects (2016) that brings together scholars wishing to challenge the artificial separation of the two because “The archival field historically has had a central preoccupation with the actual and the tangible” (Cifor and Gilliland, “Affect” 2). Especially relevant to my archival practice, and to my ensuing case study of the Aritha van Herk fonds, is Hariz Halilovich’s assessment that “researchers’ positionalities and subjectivities are an important dimension of affect in the archive and should be appropriately acknowledged” (79). By acknowledging my positionality, I consider the archived material as a site of radical listening that creates space for joyful encounters with the tangible items in the fonds while also encouraging intergenerational feminist alliances. These alliances can emerge from a willingness of the researcher to be affected by the material documenting a woman’s life/women’s lives. In the context of researching women’s writing in the 1970s, this can be an opportunity to resurface subjective truths about a time period radically different from the twenty-first century and to learn from another woman’s experience. Accordingly, a move toward a feminist archival ethics of accountability requires a relational mode of being in the archive that refuses to erase the researcher for the sake of illusory scholarly objectivity and instead wants to acknowledge the lived experience on and off the paper. I contend that the researcher’s affirmation of her affective involvement is paramount in an archival feminist praxis that considers the ethical dimension of researching, arranging, and publishing the lives of women. In strengthening her voice in the background, the researcher allows herself to be accountable for the narratives that she creates and the research ethics that she employs.

7 One of the earliest and most well-known attempts to reconcile embodied research with archival work is Alice Yaeger Kaplan’s essay “Working in the Archive” (1990), which references the twentieth-century French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline. Kaplan guides the reader through her affective entanglement with the archival material in her scholarly praxis, “attempt[ing] to move through the archival process and recover some of the stories that got deleted in the final scholarly form,” a part of the research process that she terms “suppressed meta-archival narratives” (104). Kaplan’s silencing of her own voice to highlight the legacy of a dead male author, however, seems to be especially problematic within a feminist context.

8 There has since been an effort to acknowledge the role of the researcher in arranging her archival findings and to break with the myth of the disembodied researcher. Carolyn Steedman in Dust (2001), for example, reminds us that “nothing happens to this stuff, in the Archive. It is indexed, and catalogued, and some of it is not indexed and catalogued, and some of it is lost. But as stuff, it just sits there until it is read, and used, and narrativised” (68). Highlighting concerns similar to Kaplan’s almost two decades earlier, and continuing Steedman’s work, Maryanne Dever, Sally Newman, and Ann Vickery, the authors of The Intimate Archive: Journeys through Private Papers (2009), maintain that the researcher “shap[es] the archive in [her] own image and according to [her] own research priorities”; this is “potentially productive, if not revelatory, for it is the professional researcher, together with the archivist and the librarian, who ‘create the maps and record the journeys into the archive that produce the images we have of the possibilities of the material’” (17). Drawing on their claim, it is important to note that the researcher’s narrative is already twice removed since it builds on the narrative of the person donating her material to an archive, itself already a potentially selective process, which is then imprinted with the archivist’s interpretation of arrangements. Indeed, an essential collection that brings together the voices of researchers, archivists, and writers who reflect on their archives, providing a unique range of perspectives, is Basements and Attics, Closets and Cyberspace: Explorations of Canadian Women’s Archives (2012), edited by Linda Morra and Jessica Schagerl. One important contribution is “Personal Ethics: Being an Archivist of Writers,” in which Catherine Hobbs describes how archivists “use their tools in ways that lend a false sense of neutrality” (184) since they “try to leave evaluative language out of [their] descriptions” while also risking “the pitfalls of organising in thinking that fonds map easily over [the] . . . activities [of individuals] and provide a direct link to them as they once were” (185). Most vehemently, Hobbs criticizes the communication gap between archivists and researchers in regard to the original states of order and reorder especially pertaining to fonds d’archives, giving the impression of “orderliness,” a “‘dressing up’ of personal lives” that, according to her, “diminishes the human aspect of the material and borders on the unethical” (185). As a solution, she proposes a self-conscious and earnest work ethic that should lead to documenting openly the decision-making process (189).

9 Furthermore, Helen Buss and Marlene Kadar’s influential Working in Women’s Archives: Researching Women’s Private Literature and Archival Documents (2001) brings together women researchers’ affective engagements with their subjects in archives, exploring a breadth of positionalities documenting the empathetic engagement with researching Canadian women’s archival legacies. It presents some of the practical implications of affective and ethical archival research while also acknowledging the hardships of such scholarship, noting that the contributors’ findings are the results of a “great deal of arduous work over long periods of time” (Buss 5). The strength lies in the great range of ethical considerations: from an empathetic engagement with the researcher’s grandmother’s past (Kerr); to the ethical dilemma of researching Marian Engel, who was adamant about her privacy during her lifetime (Verduyn); to editing L.M. Montgomery’s journals and having to deal with the affective responses of a large number of fans (Rubio). In the afterword, Kadar echoes both Verduyn’s and Kerr’s concerns, asking “how close to the subject can the feminist scholar be before the effect of emotional ties or the need for privacy take[s] control?” (116). My essay here seeks to add to this existing scholarship by scrutinizing an additional dimension of the ethical dilemmas explored in the collection: what are the practical and ethical implications when working with the papers of a living writer?

10 In considering the significance of the embodied writer and the disembodied writer intersecting in the archival space, I turn to Caswell and Cifor, who pose another crucial question: “What happens when we scratch beneath the surface of detached professionalism?” (25). In questioning the practices of supposed affective detachment, they pave the way for new modes of conceptualizing the researcher’s presence in the archive. I want to adapt their useful suggestion of the professional archivist as caregiver and think through what this model might look like and accomplish for the researcher in an archival setting. I contend that the researcher would not only consider her own affective entanglement but also pay careful attention to how she publicly engages with the papers of the woman/women whom she researches while interrogating her own feminist praxis in the process.

11 Such modes, inviting a more reflective research praxis, have been considered much less prominently, as the authors of The Intimate Archive (2009) point out:

To consider the implications of an active embodied presence, or “being,” it is necessary to consider the praxis of a feminist archival ethics of accountability. This is essential because “radical empathy requires closeness between researcher and subject, and the researcher [must] be fully attuned to the complexities of the research context”; if “carefully negotiated, empathy allows for a better understanding of others and their positions while also allowing us to be aware of the connections and disjunctions between the self and the other” (Caswell and Cifor 33). In the following case study of the Aritha van Herk fonds as an important feminist “repository,” I outline my research praxis of accountability while also making space for my intermittent joyful encounters with the papers.

The Aritha van Herk Fonds

12 Several aspects of my engagement with the Aritha van Herk fonds have been pertinent not only as a way of relating to her writing in the 1970s, and thus broadening my understanding of her early writing career, but also as a place of listening that, for me, has gone beyond that basic literary research premise. Instead, the fonds has allowed me to delve deeper into the wider cultural, literary, and feminist contexts of Canada at the time. The fonds is held by the University of Calgary and contains, among other items, correspondence, unpublished material, several draft manuscripts, and notes of van Herk’s creative and critical work, presenting an invaluable resource for the study of her vast oeuvre specifically and Canadian women’s writing more generally. The material spans almost fifty years and documents van Herk’s writing since 1970; not only is it an important record of a western Canadian literary history, but also it showcases what it was like to be a young feminist writer in the 1970s and early 1980s.

13 Van Herk developed her archival impulse early on, as is evident from her English school exercise books from grade eight on, drafts of her earliest poetry and short fiction, many drafts with instructors’ comments from her time as a student at the University of Alberta, and an extensive accrual related to her first two novels, Judith and The Tent Peg. In letters to her editor at McClelland and Stewart, Lily Poritz Miller, in 1979 and 1981, van Herk asked for the original unedited manuscripts to be returned to her, disclosing in a letter of 10 April 1979 that she was “developing the packrat habit of saving everything.” Poritz Miller replied that van Herk was “wise to save it [the manuscript]” (26 April 1979) and to “take care of it” (8 May 1981), since “this material can become quite valuable” (26 April 1979). And valuable would become a buzzword for van Herk’s first novel, Judith, whose Seal First Novel Award in 1978 eclipsed most of van Herk’s other creative endeavours in the years earlier and usually forms the starting point for any literary criticism of her oeuvre.

14 The fonds’ first accession, MsC53, contains 326 news clippings from between 1978 and 1984 covering the publications of van Herk’s first two novels.2 This extensive collection of material pertaining to the books’ reception is an invaluable resource to trace what to me is a shocking degree of acceptable public sexism and misogyny at the time. All reviews between 1978 and 1980 have in common, without exception, a curious fixation on the money that came with the Seal First Novel Award, no doubt fuelled by the fact that the recipient was a young woman (as is the protagonist of the book). The conscious marketing of the award and van Herk as its face led many reviewers inevitably to read the book in a quest to find out whether it was really worth the money. Whereas one reviewer observed that “there isn’t a reviewer in this country that is going to judge Judith as anything but a $50,000 book” (Peterson), another asked “What kind of book would be worth $50,000 to a consortium of international publishers? It is to satisfy this non-literary curiosity that one first opens Aritha van Herk’s Judith, winner of the Seal $50,000 Canadian First Novel Award” (Iannucci 65). Once this curiosity was satisfied, the less sensational reviews conceded that, in fact, ten thousand dollars was taxable prize money and that forty thousand dollars was an advance against royalties. Van Herk was still busy reasserting this in 2016 at her “Lecture of a Lifetime” at the University of Calgary when one of the introductory speakers proudly proclaimed that he had done the calculations himself, and the prize money from 1978 would be “180,000 grand today” (van Herk “Lecture of a Lifetime” 17:19-17:33). In the late 1970s, the general air of wondrous mystery remained, and another journalist concluded that van Herk was “a talented writer who [was] off to a phenomenally lucky start” (Barclay), consciously obscuring the hard labour of a young woman writer. Van Herk pushed back against the ingrained notion of women’s supposed gratitude and servitude, as a newspaper interviewer documented, observing that “Aritha is no weak spirit [and] has the unnerving habit of pouncing without warning, usually on people who don’t measure up to her standards, or people who try to treat her like a public commodity” (Hawkings), quoting her refusal to be labelled as the recipient of a fortuitous blessing: “I get tired of people saying I should be grateful, that I’m lucky. . . . [B]ut I’m not lucky. I worked for it, goddamn it. It’s not like winning a lottery” (qtd. in Hawkings).

15 More pressing, however, was the seeming readiness of newspaper reviews in the 1970s to equate the author with her protagonist. The negation of that equation seemed to come as such a surprise that it elicited not just a mention in the article but also entire headlines: “No, She Isn’t Judith” (Ward); “No Relationship between Author, Heroine”; “Heroine-Author Not the Same Says Winning Novelist.” “And yes,” van Herk recalled in an untitled essay, “virtually every interviewer asked me if my novel is auto-biographical, to which my standard answer is an emphatic NO” (10). The eagerness to equate women authors with their fictional characters stems from a long tradition of dismissing women’s writing as pertaining only to women’s issues coming out of their own limited worldviews. Along those lines, other reviewers concluded that “Women are certainly coming to terms with themselves in the current crop of novels by women authors” (Kilpatrick) or asked “Can’t women novelists treat women’s problems without tugging at the reader’s heartstrings?” (Maynard), concluding, however, that they can. Another (female) reviewer was put off by the protagonist’s feminist trajectory, making the protagonist “incapable of realizing that males are also vulnerable and persons like herself” (St. Goar).

16 The conflation of van Herk and her heroines continued well into the publication of her second novel, The Tent Peg (and it would crop up again with her 1998 novel Restlessness), when a reviewer was convinced that the novel’s protagonist “J.L. and van Herk are angry women. It tells in the book” (Coomer). However, the piece whose publication in a newspaper in 1981 took me most by surprise as I was sifting through the reviews was William French’s wildly misogynistic review of The Tent Peg. French claimed that “van Herk occasionally lets her feminism muddle her thinking” and then unleashed a tirade:

His misogyny peaked when, most outrageously, he wondered about the protagonist, “Will she be raped or will she be a summer virgin?” Rudy Wiebe rebuked this gross lack of judgment publicly shortly after, calling out “pitiful William French,” who had “obviously fallen into the trap the novel sets for obtuse reviewers without so much a twitch of comprehension.” The moment that I discovered the original review has stayed with me not only because it felt brutal but also because it encapsulated the unpredictability of the archival research process for which one cannot quite prepare. I had sifted through hundreds of newspaper clippings that day when I carefully put one review to the side, revealing French’s diatribe, which had sat there all along. The unexpected immediacy of encountering the review, coupled with the visceral misogyny directed at a woman whom I know and appreciate, urged me to process my emotions. In that, Caswell and Cifor’s excellent work on the role of radical empathy in the archive reminded me that a feminist approach to archival research requires “a willingness to be affected, to be shaped by another’s experience, without blurring the lines between the self and the other” (31). Thus, it has been particularly important to me to turn to van Herk’s reactions to the patriarchal landscape of Canada in the 1970s. At the time, van Herk decided not to respond publicly to French’s deliberately hostile misreading of her novels, but she writes, for example, about her affective response to the common sexism in an essay in her collection In Visible Ink: Crypto-Frictions (1991):

17 Van Herk’s strong reaction to male critics’ engagement with her works also showcases her immediate bodily response to the misogyny experienced in everyday life and transferred onto paper. As Cvetkovich reminds us, “cultural texts [can be] repositories of feelings and emotions, which are encoded, not only in the content of the texts themselves but in the practices that surround their production and reception” (7), and can stay with a text, or a review, even if it is encountered forty years later.

18 The collection of newspaper clippings, in connection with correspondence and publicity material, further highlights the fonds as an important “repository” of a Canadian literary history. As Dever, Newman, and Vickery point out, “the significance of ‘auto-archival’ practices should not be overlooked,” affirming that the act of preserving documents of a certain time period, as well as official and private correspondence, is an important means to privately archive the national culture (12). Accordingly, the Aritha van Herk fonds emerges as a testament to her prolific writing career that preceded the publication of her first novel. Apart from her literary publications, they also uncover her rich contributions to the literary and cultural life of Canada, for which van Herk was invested into the Order of Canada in 2019.3

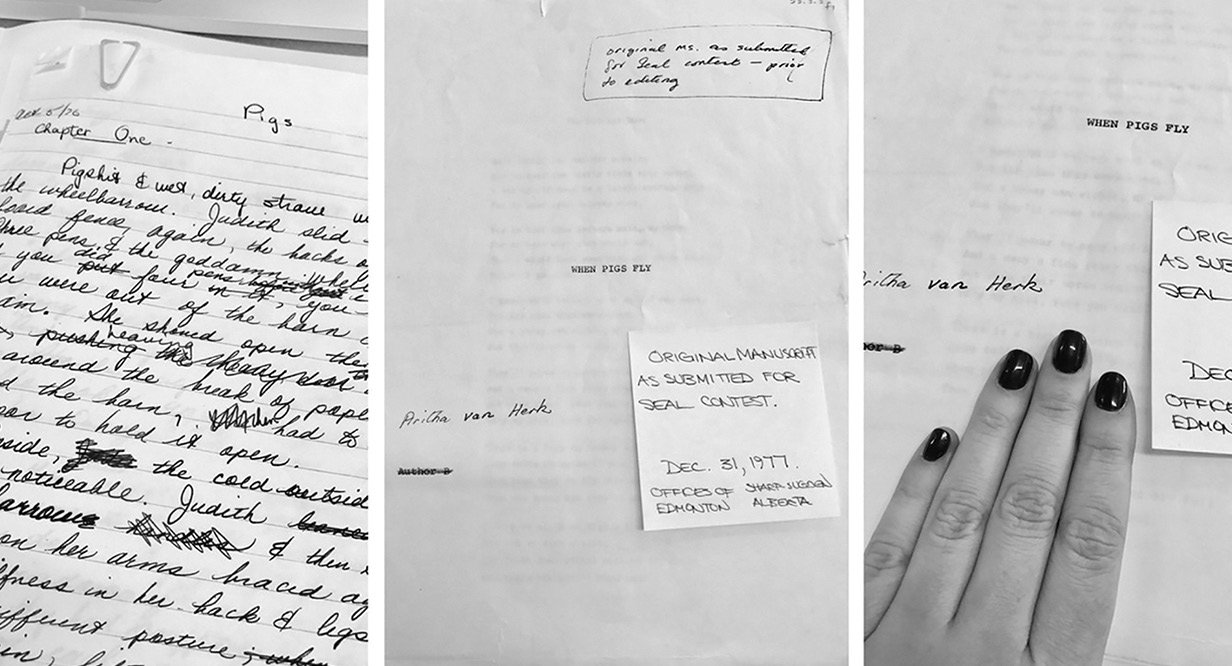

Paper(s) and Affective Responsibilities

19 Women’s archival material from the 1970s can also be a site of inter-generational feminist dialogue, providing meaningful contextual information for new generations of feminists. This does not extend solely to the historical and cultural contexts, such as the reviews discussed previously, but is also an important means to trace changes in mode and materiality of communication. “Given this obsessive involvement with paper,” Dever, Newman, and Vickery observe, “it is ironic how seldom we comment on the physical properties of the documents we covet so intently,” running the risk of “los[ing] sight of their status as material culture, and consequently, fail to extend our reading habits to encompass the realm of literacy” (29). Born in the late 1980s, I am perhaps of the last generation who grew up in a semi-digital environment, still remembering floppy disks, life without mobile phones, and teenage years without social media. Immersing myself in the writing life of the 1970s has given me a fresh perspective on the pace, etiquette, and physicality of communication during that time period, as well as the delight in exploring many hand-annotated drafts, learning much about the craft of editing, and finally helping me to resolve the mystery of the double space after a period. Working predominantly on twenty-first century women’s writing with usually few opportunities to engage with archival material, I was overcome by a strange sense of satisfaction as I looked at my dusty and itchy hands covered in paper cuts after a month of rummaging through old newspaper clippings. It was exhilarating to discover visible traces of my labour that extended beyond the tired eyes and a sore back that usually come with a good day’s work. Most of the archival material that I reference here stems from the fonds’ first accession, MsC53, which holds the bulk of material pertaining to van Herk’s first two novels and consists of 926 items spreading over 7,700 pages. Included in this accession are the typescripts that would later go on to become the prize-winning novel Judith, correspondence, proofs, newspaper clippings, promotional materials, and photographs from 1973 to 1984. The further back in time I worked myself in the fonds, the more important it became to discover the material with my own eyes and to explore the tactile dimension of archival research. Touching the papers helped me to map out and remember items more easily, and holding in my hands manuscripts and drafts that thus far I had only read about created moments of immense joy (see Image 1). The fonds is still expanding as van Herk continues to donate material. With technological advances, correspondence and word processing have moved almost entirely into the digital realm, transforming more recent accessions into a uniform blend of white paper containing email thread printouts and typed drafts, making them more difficult to distinguish.

Display large image of Image 1

Display large image of Image 1

20 As I was moving back and forth in time researching the papers, I became acutely aware of the infrastructural peculiarities of the disembodied and embodied writer, since the University of Calgary is home to both: the Aritha van Herk fonds and Aritha van Herk’s professional life since 1983. I was therefore presented with two crucial intersections. On a practical level, this meant that as a foreign body I was able to feel my way into a city and a landscape intimately tied to van Herk’s writing. Looking up at the vast prairie sky from the bright and spacious reading room of Archives and Special Collections while reading drafts of stories and novels that reference women in those spaces has had a long-lasting impact on how I relate to van Herk’s fiction and my appreciation for her craft. For van Herk, writing has always been a deeply personal and emotional process, as she explains in “Why I Write”:

Taking into account van Herk’s vulnerability as expressed above, and the additional overlapping of spaces, where the embodied writer and the disembodied writer intersect, meant for my research methodology that an empathetic approach to the archival material seemed to be even more pressing and required an additional layer of accountability. In this temporary spatial overlap, in which the material, the writer, and the researcher meet and connect, it is all the more important to consider a feminist archival praxis in which I engage ethically with the material to which I have been granted access while also considering the writer’s own emotional entanglements with her papers, which van Herk mentions in an article from 2008:

I felt that I needed to hinge an affective responsibility on acquainting myself with these “friends.” During my first stay at the University of Calgary in the summer of 2016, I struggled initially to shake off an unexpected feeling of discomfort that I was intruding on van Herk’s life, being privy, for example, to correspondence never meant for my eyes. I had never researched the papers of someone who was still alive and, more pressingly, in reach. My feelings of discomfort were further complicated by the curious asymmetry that seemed to unfold in how the relationship between me, the researcher, and Aritha van Herk, the writer and person, developed in those first few weeks of archival research. Through my rapid acquisition of knowledge from the fonds, the relationship seemed to accelerate in a consistently one-sided manner that left me with a skewed sense of intimacy since I was discovering so much about her life while she knew very little about mine.

21 During that time, I had to negotiate how I could best reconcile what felt like a false intimacy cultivated in the archive with the actual living person. Although the non-reciprocal nature of the relationship between researcher and subject might be a common occurrence in many archival encounters, the palpable imbalance was intensified in my case, for van Herk is employed by the same institution that houses her papers, and I met her regularly while I was working on them there. On some days, this meant spending six hours in the Special Collections reading room on the fifth floor of the Taylor Family Digital Library, retracing van Herk’s career in the 1970s, then stepping out of this time warp and taking the elevator to meet her in the flesh for a coffee in the small café on the ground floor.

22 “Doesn’t that feel weird?” is perhaps the question that I get asked most frequently by friends and colleagues when they learn about the particularities of my archival research. The initial feeling of “weirdness” wore off quickly as I continued to follow my approach to the archived material that I considered as a site of radical listening and intergenerational feminist alliances. During our encounters, I first and foremost listened to van Herk and asked her questions. The most generative and joyful aspect of those conversations for both of us, I think, has been the joint exploration of the fonds. While I was discovering many texts, letters, drafts, and photographs from the 1970s for the first time, she was rediscovering them alongside me as I asked questions and showed her images of the material on which I was working. Exploring some of it together was one way to shift my perceived relational one-sidedness of the archival research process and to mobilize my accountability.

23 A feminist archival ethics of accountability can provide a mode of engagement that treats these archival matters with empathy. In that, I return once more to the work of Caswell and Cifor on empathy in archival work in which they offer a series of questions that archivists could ask themselves in the process of arranging someone’s papers: “[W]ould the creator want this material to be made available? In making descriptive choices, . . . what language would the creator use to describe the records? In making preservation decisions, . . . would the creator want this material to be preserved indefinitely?” (34). Crucially, they state that an ethical approach in which the archivist, or in my case the researcher, asks herself these sets of questions in order to take into account an emotional attachment to the material and consider the writer’s privacy under no circumstances equals censorship or “that the wishes of the creator trump th[ose] of other interested parties” (34). Andrea Beverley neatly outlines her ambiguous feelings while navigating the Daphne Marlatt fonds during which she struggled with questions of privacy and intimacy of information and the possible implications for third parties who did not agree to appear in someone else’s archive. Beverley also admits that in the end her research led her to address “the complex ethical questions of [her] own use of archival research” (160), coming up against hard questions. She draws on Christl Verduyn’s work on Marian Engel (162). Verduyn grapples with similar difficulties, referring to Joan Coldwell, who asks “‘How intimate is intimate?’ and ‘How can one justify the intrusion?’” (Coldwell, qtd. in Verduyn 93).

24 In a research methodology grounded in a feminist archival ethics of accountability, the focus is on the formulation of the difficult questions that the researcher needs to ask herself. Instead of “How can one justify the intrusion?” the researcher could ask herself “Is this intrusion necessary? Will this intrusion benefit my overall research on the person’s papers in a positive way? Does the scholarly revelation outweigh the discomfort that it might cause the person whose papers are being scrutinized?” In my feminist archival praxis, I ask myself these questions regularly. An ethical and feminist approach to the papers of living women writers must also pay particular attention to the patriarchal conditions under which women’s work is often produced. Following, for example, an “ethics of particularism,” as configured by a feminist ethics of care (see, e.g., Robinson), would also allow the researcher to make space for individual differentiation rather than follow universally applicable rules, thus creating a framework that can accommodate the diversity of women’s experiences and archival constellations. This case study is one such attempt to reflect on a particular set of circumstances, for a single experience can also be indicative of a collective experience that might be adopted in part to account for the broad range of archives, feminist researchers, and women writers.

25 What initially got me thinking about a feminist archival ethics of accountability was my own fear of self-censorship. It took my second research stay for me to realize that choosing not to disclose certain findings made me not a dishonest but an ethically responsible scholar. Fonds that document a human life will contain traces of conflict, sadness, and loss, and as with other private conversations, I have decided to keep them between me and the past van Herks. In one instance, I came across an early draft of a text that contained personal details, and though some of it might have been an interesting addition to discuss the evolution of the text, and the literary scholar in me was tempted, I decided that the scholarly gain simply did not justify the intrusion. I am fortunate that, where I feel unsure about the ethical markers in my archival research, I am able to ask van Herk about her own preferences. An ethical and accountable approach to working with archival material by a living writer, the only experience that I can draw on at this point, means, above all, transparency in how I plan to use material from the fonds and how I intend to frame it and to what end. I am lucky to work on the oeuvre of a writer who is generous with her time and, more importantly, who neither demands control over my research output nor exerts pressure on me. I am convinced that it is only through good communication that we can reach an ethical responsibility for the narratives that we create from the material with which we are privileged to work.

I would like to thank the International Council for Canadian Studies, whose Graduate Student Scholarship allowed me to conduct the archival work referenced in this essay, as well as Allison Wagner and Annie Murray from Archives and Special Collections at the University of Calgary for their generous assistance.