Articles

Revisiting Sylvia Fraser’s Pandora:

Girlhood, Body, and Language

1 In my 1987 PhD dissertation, The Romantic Child in Selected Canadian Fiction, I included Sylvia Fraser’s 1972 novel Pandora in a final chapter in which I discussed Fraser’s text along with other autobiographical fiction: Margaret Laurence’s A Bird in the House (1970), Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women (1971), Audrey Thomas’s Songs My Mother Taught Me (1973), and Marian Engel’s No Clouds of Glory (1968) (Steffler 265-90). I later taught Pandora in Canadian literature courses at Trent University in the 1990s, but it was not a prominent novel at the time and has since become even more obscure. A well-received text in 1972 when it was first published,1Pandora touches on many issues that remain central to twenty-first-century Canadian literary girlhoods. An imaginative and precocious child, Pandora Gothic experiences abuse, bullying, patriarchal domination, and a general fear of ominous forces within her home, town, nation, and world. In the afterword to the 1989 New Canadian Library edition of the novel, Lola Lemire Tostevin points out that “Pandora was well ahead of its time in its displacement and reconceptualization of prevailing myths about motherhood, nuclear family, language” (258-59). She also maintains that “so much has been written around women’s relationship to language since the publication of Pandora that it would be negligent not to examine its relevance to the novel” (260). Tostevin sees in the character and the novel itself a “yearn[ing] to escape the rigid forms” of language assumed to be “indisputably correct” and argues that “traditional linguistic forms” are exposed as dangerously “restrictive” and “controlling” (261) in the course of the narrative. Lorna Irvine, also focusing on language in her 1984 article, “Politicizing the Private: Sylvia Fraser’s Pandora,” argues that Pandora is “based on material that has traditionally been devalued — the female body — and told in a language that has traditionally been ignored — a women’s language” (225).

2 According to Tostevin, “new readings of psychoanalysis, mythology, theories about language, and feminism” by 1989 had exposed “Freudian concepts” as “patriarchal projections” and Western “myths, religion, philosophy” as “misrepresentations” that “reinforce masculine contempt towards the feminine” (258). She sees such exposure at work in Fraser’s novel, resulting in “the mythical Pandora” being “displaced by a new Eve” (261). Irvine, in her interest in the private and public, focuses on the “interplay between male dominance and fascist ideology” (233), concluding that “Pandora will not wait to be chosen,” but “will control her own life, will be a subversive new woman” (233). The new Eve or subversive new woman emerges, I argue, from the close relationship between Pandora’s body and language as established in the very early years of her childhood. The most striking and radical aspect of Pandora is its focus on the formation of the language of girlhood as the child develops from a preliterate to literate state.2 In this article I examine the relationship between language formation and the developing girlhood body as a subversion of patriarchy and as the foundation and basis of the new woman identified by Tostevin and Irvine. I return to Pandora in 2019 in order to examine the language of girlhood as thought, imagined, written, read, heard, and spoken by Pandora Gothic in a form of resistance against patriarchal, classist, and ageist enforcements of the young girlhood body into prescribed spaces. Girlhood language, which Pandora both perceives and creates through her response to sounds, words, pauses, and rhythms, plays a major role in her attempts to cope with her family and society and in her strategies to break free from oppressive forces that dominate her life and development in Mill City, which is closely modelled on Fraser’s hometown of Hamilton, Ontario. Fraser’s Bildungsroman is remarkable, then, for its concentration on the very young girl3 — the novel covers Pandora’s life from her birth in July 1937 to the spring of 1945 when at the age of eight she reaches the end of grade two — and is unusually successful in its focus on the early years in which language is formed, creatively experimented with, adjusted, and adopted in order to become the child’s own.

3 Such child acquisitions of language are seen in earlier prose works such as Emily Carr’s The House of Small (1942),4 but Pandora’s emphasis on the range and forms of oral, written, and imagined words sustains an unusually concentrated focus on girlhood body and language, which emerges as a major theme in the novel. The result is an intricately complex exploration of linguistic and bodily resistance, which anticipates the relationship between girlhood language and bodies depicted in later works such as Adele Wiseman’s Crackpot (1974), Joy Kogawa’s Obasan (1981), Ann-Marie MacDonald’s The Way the Crow Flies (2003), Heather O’Neill’s Lullabies for Little Criminals (2006), and Miriam Toews’s The Flying Troutmans (2008). In her 1974 review of Pandora in Canadian Literature, Pat Barclay commented on the language of the novel as a whole: “Pandora’s prose style is original and impressive. Its pages sparkle with metaphor and divert us with carefully-researched 1940’s detail, from Pandora’s Sisman scampers to the uncomfortable hickory bench at the bank” (110). These historical and cultural details may come as much from Fraser’s remarkable memory as from careful research, but in any case the details, along with the “sparkl[ing] with metaphor” prose style, account for much of the power of the novel and the vitality of the title character.

4 Laurie Ricou’s Everyday Magic: Child Language in Canadian Literature, published in 1987, includes discussions of Munro, Laurence, Carr, Miriam Waddington, P.K. Page, and Dorothy Livesay, but there is no mention of Fraser or Pandora, which is arguably the richest and most extensive treatment of girlhood language in a Canadian novel up to that point. The omission indicates the low profile of Pandora by the mid-1980s. Attention accorded to language in general is immediately apparent in the novel’s remarkable opening paragraph announcing Pandora’s birth: “And she brought forth her fourth-born child out of flesh-heave, mountain-burst, joy-throe, pain-spasm, silt, seaweed, dinosaur dung, lost continents, blood, mucus and genetic hazard, and she wrapped her in white flannel, and she laid her, struggling, wheezing, spewing, in the ragbox by Grannie Cragg’s treadle machine” (9). Sandra Sabatini’s lack of reference to this infant birth in her 2003 study, Making Babies: Infants in Canadian Fiction, confirms the continuation of the low profile of Fraser’s novel into this century.

5 In 1988 Fraser published My Father’s House: A Memoir of Incest and Healing, which provides disturbing autobiographical contexts and intersections for the girlhood language of the fictional Pandora. Fraser included an author’s note in the 2011 digital edition of Pandora, explaining the relationship between the memoir and the novel in terms of the recovery of lost childhood memories.5 Although I write with the knowledge of My Father’s House and the “Author’s Note,” I do not attempt a reading of autobiographical trauma in Fraser’s novel. I examine instead the novel’s language itself, proposing that it is through the rhythmically persuasive use of oral and imagined language in conjunction with nursery rhyme and fairy tale elements that Pandora, setting herself against the rigidity and authority of print culture and traditions, bravely negotiates associated threats of violence that lurk in all corners of her 1940s’ small-city southern-Ontario world — in domestic, neighbourhood, school, and public spaces as well as in the Second-World-War paranoia that infiltrates Oriental Avenue, Mill City, and Canadian society.

6 Fraser’s novel includes nine line drawings of Pandora by Harold Town, which reinforce the character’s muted but insistent physical presence. The drawings on largely blank pages with minimal context suggest a world separated from the everyday — an airy and imaginary realm positioned above and in opposition to the upper-case, bold, large-font world of Oriental Avenue and Mill City. Although the richly suggestive illustrations by Harold Town have their own intriguing story and much to add to a discussion of the materiality of the text, I am limiting myself in this article to words only — words as they appear on the page, on signs and plaques, in advertisements, in letters, and as they are spoken, heard, read, recited, and sung by characters in the novel.

7 In Corruption in Paradise: The Child in Western Literature (1982), Reinhard Kuhn probes the abstract nature of childhood language, noting that when “faced with this elusive language, the writer is forced to focus his attention not directly on the child but on the reaction to him, and that is why we must resign ourselves to being satisfied with the adult perception of the child without giving up the hope of some day gaining an insight into his reality, or an approximation thereof” (61). Similarly, Richard N. Coe, in When the Grass Was Taller: Autobiography and the Experience of Childhood (1984), argues that “the child sees differently, reasons differently, reacts differently” than the adult and that “the experience of childhood . . . is something vastly, qualitatively different from adult experience, and therefore cannot be reconstituted simply by accurate narration” (1). Susan Honeyman speaks of “the inaccessibility of childhood in literary representations by writers self-conscious of the ‘impossibility’ of the task” (21),6 while Ricou focuses on child language as the crux of this dilemma when he observes that “the writer, it seems, must use enough child’s language to give a consistent feel of what the child would say, yet exploit fully his mature technical resources to suggest the complexity of the child’s mind” (2). Ricou refers to Theodore Roethke’s theory that getting child language right necessarily involves attempts at creating the “‘as if’ of the child’s world” (Roethke qtd. in Ricou 2). And this is exactly what Sylvia Fraser does so brilliantly in Pandora. She does not resign herself to the adult perception of the child, the position assumed as inevitable by Kuhn. Pandora is an extraordinary rendition of childhood precisely because the language is intrinsically of that world. Fraser is not held back by the “impossibility” of the task, but writes a book that revels in the challenge of getting child language right.

8 The orality of early language is its most distinguishing feature, as Ricou makes clear in his references to Peter de Villiers’s and Jill de Villiers’s findings in their 1979 study, Early Language (Ricou 5). These findings include the observation that “in the earliest stages of development the child’s speech is very much tied to the here and now” rather than to the past, future, or hypothetical (de Villiers 84). According to Early Language, “the child begins to speak bound by circumstances; he ends by using language to invent circumstances” (85). These qualities of early language development, according to Ricou, “are crucial features germane to any discussion of the child in literature” (5) and are certainly featured in the evolving language of Pandora Gothic, who quickly learns to invent narrative in order to survive and resist. As Elana Newman explains, “one major developmental task during childhood is to master basic linguistic skills that are needed to put information into a narrative structure” (23-24). In addition to using oral language in creative and articulate ways, Pandora indulges in the language of the imagination, which is made accessible to the reader through a complex narrative voice and the author’s creative use of the versatility of fonts and white space on the printed page.

9 The tension between the rigid and authoritative language of society and the imagined language of the child is the basis of Pandora’s feminist subversion of patriarchal pressures. The attempt to reproduce child language on the printed page in order to lift it to an oral register and then to a more ephemeral plane conveying the child’s thoughts and imagination involves a linguistic partnership between the narrator and Pandora in which the points of view between the two both alternate and intersect. At one point, for example, the narrator comments that “Arlene [a friend] and Pandora — without exactly putting it that way — instinctively harken to the more romantic Creation Theory” (48, emphasis added) of the origin of Wilde Corner in Paradise Park. The narrator serves as a type of translator of the girls’ thoughts, articulating a position and employing terms beyond their knowledge and experience in order to provide an accurate reading and rendition of their opinions. David Staines, in his introduction to the 1976 New Canadian Library edition of the novel, outlines how “the author moves inside Pandora and her world through an intricate positioning of her omniscient narrator,” who can address the reader with “detached ironic humour” or “the insight of a sensitive psychologist,” but most importantly “creates a distinctive narrative voice which flows naturally with the imaginative leaps of Pandora’s own mind” (xi). Rae McCarthy, in a review of the novel, contends that “extending beyond the central core of Pandora’s consciousness, yet merging smoothly with it, is the voice of the narrator who sees and re-creates a world around Pandora while recording the child’s reactions to it” (703).

10 This complex narrative voice — both part of and apart from Pandora — manages to be companion, guide, and commentator without condescending to or excluding the child. In line with the fairy tale qualities of the novel, the narrator functions as a fairy godmother figure, drawing out and blessing the power of fancy and imagination to challenge and overturn patriarchal fonts and stances on the novel page and in the Mill City world depicted on those pages. It was, after all, in the 1970s that feminist revisions of fairy tales flourished, and Fraser, writing Pandora in this decade, develops the character and novel within this revisionist spirit, which includes setting up a partnership rather than a hierarchy between the young girl and the fairy godmother figure.7 In an early scene the narrator, noting how Pandora carefully avoids touching the poison plants in Grannie Cragg’s poison pocket, moves into Pandora’s mind in order to explain that “Pandora only thinks their names: To say them aloud would poison her mouth. Even to think them makes her tongue prickle. Pandora crosses her eyes. She spits” (17). The narrator not only understands the child’s linguistic strategies and respect for the power of plant and language, but endorses them. By affirming and reinforcing Pandora’s ritualistic and practical behaviour, the narrator participates in protecting her from danger. The close connection between language and body is apparent in the way that even the thought of a word causes a prickling tongue. Through deliberately using her body to cross her eyes and spit, Pandora manages to contain words within her mind, in this case the names of poisonous plants, thus controlling any urge to voice them aloud — to release them — and expose herself to danger.

11 More than simply the “helper” figure in the fairy tale, the fairy godmother often has aspects of the absent or ineffectual real mother.8 Indeed the fairy godmother/narrator serves as a maternal guide to Pandora in a way that her own mother, Adelaide, does not. In a sense Pandora creates her desired version of Adelaide as mother, based on her relationship with the narrator. Interpreting Adelaide’s hymn-singing as an escape from the heaviness of her body and world — “My mother has slipped from her skin. My mother has flown out of her body to be with her songs” (11) — she sees more in Adelaide than simple subservience. Pandora takes her mother above the oppressive material world for just an instant in order to escape, just as Pandora, with the help of the narrator, lifts herself above negative reflections of herself in mirrors and the eyes of others.9 The child carries the mother in a manner similar to the way in which the narrator carries Pandora.

12 With deliberation and increasing awareness Pandora works in partnership with the narrator, who travels alongside her in the italics that rise above the sordidness of Oriental Avenue. The close relationship between the narrator and the child character she understands and nurtures so intimately provides the reader with access to the articulate language of girlhood. This revelation of language occurs in conjunction with the reader’s acute awareness of the positioning of the girlhood body as an important context and source of the words spoken.

13 The first few pages of Pandora are filled with italicized text, setting up the tension between Pandora, in partnership with the narrator, and the rest of her family. At one point Pandora’s older twin sisters, Adel-Ada, are reading aloud The Bobbsey Twins at Home in “sentence turnabouts,” using their voices responsively to lift the written words off the printed page while the naked Pandora fights back against her mother’s attempt to lull her to bed by singing “Rock-a-bye Baby.” Pandora insistently prolongs her resistance to her mother’s coaxing by digging into various body orifices, extracting a grain of sand from one ear, a flake of wax from the other, “a shred of cotton from a crack in her big toe,” “a dot of corduroy from her bellybutton,” bringing forth both natural and foreign fragments from the inside and surface of her body. When Pandora spreads her legs to reach for the warmest opening, Adelaide strikes her on the face, leaving “a scarlet stain, the shape of a hand” spreading across one cheek and then, with a smack across the other cheek, marks the young body with a second recriminating sign of shame and guilt (12-13). The violence of the unexpected slaps shockingly interrupts the maternal lullaby and the structured reading performed by twins about twins.

14 Pandora’s marked body releases more than a shred of cotton or a dot of corduroy during the night when “liquid scalds [her] thighs” and “gushes through flannel ditches.” The lack of control and the physical betrayal of the sleeping body are greeted by Pandora the following morning with an italicized thought narrative of “The Princess and the Pea,” which turns on the line, “Dear Pandora, you have felt the pee through twenty mattresses and twenty eiderdowns. You are a Real Princess!” (13), spoken by the increasingly familiar fairy godmother narrator, who tends to be close to the italicized text. The wordplay on pee extends into fantasy as the urine is transformed from weighty and cold clamminess into a shiny stream of stars ascending into constellations in the sky, playing into the language and narrative of myth: “the pee ascends in a golden chamberpot, up into the sky, and there it shines today, just under the tail of Sirius, the dog star, unless someone has stolen it” (13-14). The godmother figure is traditionally the origin of transformations in folk and fairy tales and Fraser is definitely playing with this convention here.10 Although the myth is part of Pandora’s thought narrative, the scene has been set up by a narrator who both controls and reflects Pandora’s own mind and diction as she introduces the morning setting: “The sun breaks like a fresh egg through Pandora’s window” (13). It is through fanciful language, “sparkling metaphor” in the form of simile, and imaginary story, both within Pandora’s mind and as bestowed upon her by a wordsmithing narrator, that the child moves — through italics — from the twins’ exclusion and her mother’s smacks into a realm and narrative lifted far above her everyday world, where her marked and leaking body lies betrayed by the solo of the maternal lullaby and the duet of her sisters’ responsive reading from the printed book.

15 In a later episode Pandora’s body and language are involved in much more violent interchanges with her father, Lyle Gothic, an ogre-like monster — a butcher by trade — who has a hook for a missing hand. Immersed in early reading during a period when “she no longer needs the letters” (89), Pandora often recites and hums Fun With Dick and Jane, which she is doing when Lyle’s fist violently slams down on the table in response to Pandora daring to feed the cat, Charlie-Puss, during a family meal. Lyle’s slam is met by Pandora’s two fists crashing down in unison, her left one landing in “her Tranquility Rose turnip garden, and her right one in her lemon jello” (90). Rocking on her haunches in the cellar closet after being swiped from the table by Lyle’s hook, Pandora recites “all of A Doll for Jane, What Sally Saw, and Puff Wants to Play, not forgetting the periods and the commas” (91). When somebody sneaks Charlie-Puss into the closet, Pandora, in stroking him, realizes that “Charlie fills his skin, and he is happy in there.” As Pandora tries to find herself within her own skin, she laments: “Sometimes I am so big I burst my head. Sometimes I am so small I rattle in the end of my big toe.” Experiencing a desire to “get out of [her] skin,” Pandora notes how her parents manage to accomplish such escapes, her mother “through her mouth” as “she slides out on her treble clef,” and her father in a violently disgusting way by “explod[ing] his skin.” The reference to Lyle’s explosion takes Pandora to its disturbing aftermath: “He splatters everyone with hot skin, and then he grows another.” The nightmare grows as she notes that he “sucks in all the air in the room, and everyone else has to squash themselves against the wall, and rub off their noses so as not to prick him.” Pandora can feel Lyle in the closet, “sucking the air from her lungs” and “pressing against her chest, like a big, black boot” (91).

16 The ominous presence of Lyle emptying Pandora’s body of air, the source of speech and life, and flattening her chest with the Nazi-like boots that become a terrifying motif in the novel points to the failure of Pandora’s recitation of words to protect her in this particular case. It seems that the words of Dick and Jane are too prosaic to cast a protective spell or to bring girlhood language and body together into wholeness. Marina Warner points out that “spells are formed of repetition, rhyme, and nonsense; when they occur in fairy tales, they’re often in verse — riddles and ditties, and they belong to the same family of verbal patterning as counting out, skipping songs, and nursery rhymes” (31), which Pandora picks up in abundance in her neighbourhood and schoolyard, but does not use in the terrifying darkness of this cellar closet. The recitation and humming of the printed word offer numbing protection, but the primer style falls short in terms of providing the verbal power to protect and transform. A less prosaic and more magical narrative is needed.

17 The literal comfort of Charlie-Puss in the closet “reaching out a reassuring paw” from Adelaide’s galoshes (91) initiates the much-needed narrative — an elaborate italicized story of Puss-in-Boots tricking and consuming the giant boot when it foolishly turns itself into a mouse. This italicized narrative, followed by the bracketed and upper case TO BE CONTINUED (92), confirms the words as a form of protection and resistance woven by Pandora within her mind and imagination. The reduction of the giant through his stupidity and pride allows the weaker victim to consume the boorish ogre. The feeling of being both too small and too big for her skin is not then, as Pandora realizes, a hopeless or static condition. Words and story can transform and empower the teller of the tale as well as the victim within the tale. As the words take shape in Pandora’s mind, the insides of her body (the guts and emotions) fill her skin to the point of eliminating the rattle of smallness without swelling to the point of bursting through the body’s surface. Marked and stuffed into small places, Pandora’s body fights back by counteracting Lyle’s upper-case shouts and bodily pressure with the transformative words and power of the italicized and personalized font of the folk or fairy tale, which manages to accomplish what the ritualistic recitation and humming of Dick and Jane could not. The recitation and humming, however, serve as preparation and training for the more ephemeral and powerful narrative of the mind and imagination as Pandora lifts the everyday, plain Dick and Jane, made accessible by her recently acquired reading skills, from print, rote, and humming into italicized font and fairy story — into lightly traced words that subvert the rigid and authoritative narratives of her 1940s anything but “Dick and Jane” family and society, thus protecting her from domestic darkness as well as from the heavy rumours and fantasies of Nazism and war atrocities in Europe and the Pacific.

18 The horror and fear of the war occur throughout the novel, suggesting correspondences between the local grotesqueries that occur in Pandora’s own neighbourhood and the more public atrocities that take place overseas. Italicized nursery rhyme lines are juxtaposed with uppercase newspaper headlines as Pandora’s humming of “Old King Cole was a merry old soul” moves through Adel-Ada’s oral reading in sentence turnabouts of The Bobbsey Twins Keeping House to confront the print headlines of the newspaper Lyle Gothic is perusing: “COLOGNE STILL BURNING FIERCELY” (19). The war tends to exist in upper-case font in the novel and in Pandora’s world. In a notice on a telephone pole, for example, Pandora reads: CANADA NEEDS ALL YOUR WASTE PAPER! (40). Patriotism, based on fear of the enemy, is demanded of all citizens, including children, through upper-case shouts.

19 The focus on the materiality of language based in the fonts and formats used in these particular passages are only a few of many examples in the novel. Pandora’s pages are filled with a variety of written texts ranging in content from political propaganda to girlhood culture and in form from engraved plaques to elusive singing and humming. Versions of oral narratives include sermons, songs, hymns, prayers, and playground rhymes. The literary text reproduces the range and variety on the page itself. Within this range and variety the italicized languages of Pandora’s mind and imagination dominate; with confidence and audacity this language begins to speak back to, and over, the small-minded and threatening language of the family, institutions, and society in which Pandora lives.

20 The printed page opens up areas of tension between girlhood and the institutions and authority that attempt to contain and control it. In a very concrete way the material text embeds on the page the tension between girlhood language and patriarchal forms of linguistic and narrative control. A variety of font styles and sizes, along with typographical emphases such as italics and bold, appear throughout. In the text’s scripting of the tension between Pandora and Lyle, for example, Pandora’s italicized humming of Dick and Jane at the dinner table gradually confronts Lyle’s upper-case shouts as the italics and capital letters march closer to each other on the page and at the table. The fictional Puff becomes entangled with the real Charlie-Puss as the hummed story-narrative takes on the real dinner-table panic and turmoil, culminating in “Run, Puff, run” morphing into “Run, Puss, run” (90). This minor replacement of double “ss” for double “ff” in the transition of the fictional Puff into the real Puss is the result of the intrusion of Lyle’s violent words into the clearly organized and neatly arranged prose of Dick and Jane. The repetitive letters, words, and syntax of the primer text on the pages of the reader are lifted by Pandora into oral recitation and further transformed by her at the supper table into humming. When Pandora’s humming comes into contact with Lyle’s yelling, the Gothic family dynamics and sounds infiltrate the italicized rhythm of Dick and Jane, resulting in a shift from Spot and Puff being encouraged to run playfully to Adelaide, Adel, and Ada being warned to run away from Lyle. The hummed thought narrative of Pandora transforms into internal warnings to her family, making use of the diction and syntax of the recently acquired language of the school reader. Pandora “no longer needs the letters” (89) on the page because she has absorbed them into herself to the point that they are part of her and she can adjust and use them as needed.

21 In another confrontation between registers of print on the page, in school rather than at home, repeated letters and words are pitted against each another in a struggle for volume and control. The school intercom infiltrates the classroom with the sounds of “buzzzzzz” and the command of “ATTEN-SHIIIIIIIIUN” from Col. Percival Burns. Room 3 responds by getting up from their desks and “flip flip flipping their seats in noisy forgetfulness” before they are ordered and managed into regular and controlled lines and behaviour. The light sounding, lower-case, italicized “flips” create barely a ripple in the face of the harsher repeated letters and the quickly formed two-by-two lines of students, “with the shortest in front of the tallest, and the girls in front of the boys, and each teacher leading her own contingent hup! hup! hup! beating 4/4 time on the hollow floors with the Cuban heels of her black oxfords” (83). The volume and heaviness of the adult and authoritarian sounds and movements in the school easily eclipse the light and thoughtless flipping sounds made by the children. The forcefulness of the commands and the militaristic regularity of the lines and marching suggest ways in which domestic attempts to regulate unruly behaviour are similar to political attempts to impose order in the public sphere.

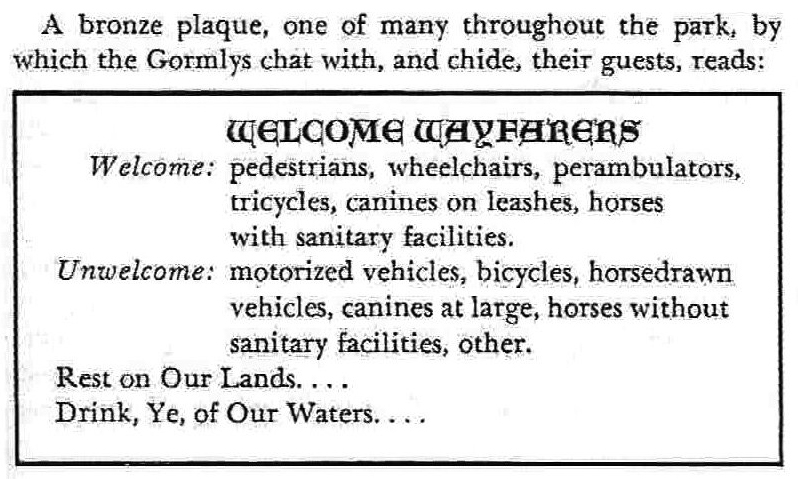

22 Signs, fliers, and plaques in public places provide cultural, social, and political information, often conveying contradictory messages or at least tensions. The “Welcome Wayfarers” bronze plaque in Paradise Park (see Figure 1), for example, both includes and excludes the citizens of Mill City, depending on their methods of transportation and whether they are accompanied by leashed or unleashed dogs.

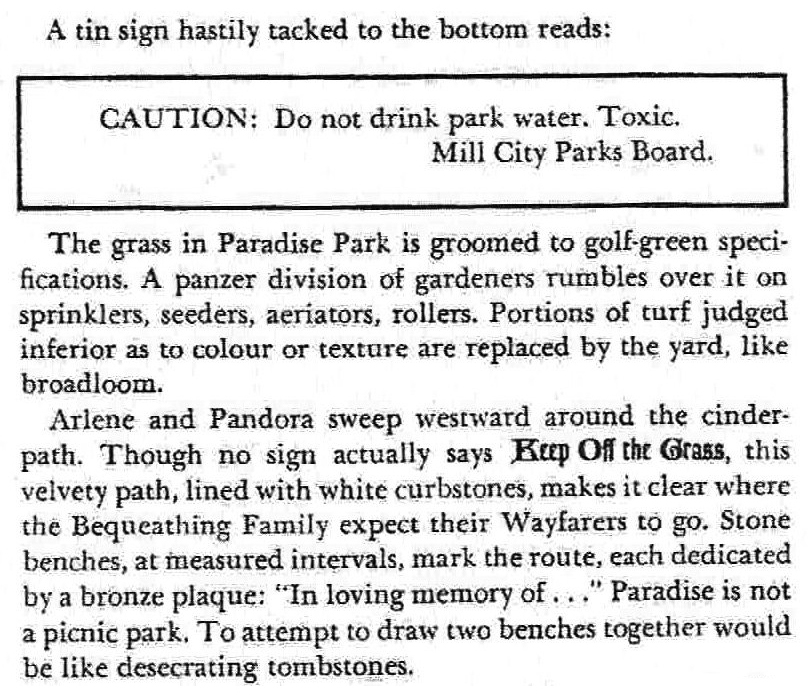

Pandora and her friend, Arlene, who arrive by tricycle, are welcomed by the plaque. Their actual experience in Paradise Park, however — being flashed by a scruffy man in a raincoat — proves that the “welcomed” pedestrians are not necessarily as desirable as the official policy assumes. Attached below the bronze plaque is a cautionary tin sign warning of toxic water (see Figure 2), problematizing the older and more permanent invitation to “Drink, Ye, of Our Waters” (see Figure 1) immediately above it.

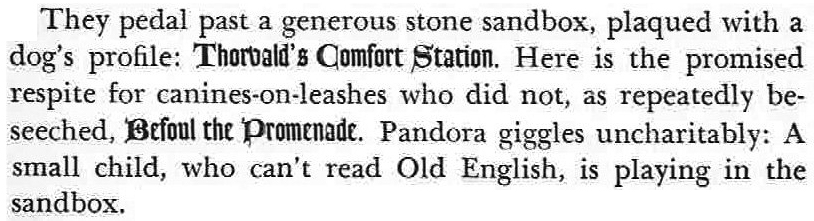

The bold, Old English font “Keep Off the Grass” in the text of the novel occurring below the reproduction of the cautionary sign does not actually exist, but functions as an invisibly insistent command to Pandora and other park-goers as conveyed through the non-verbal message supplied by the “velvety path, lined with white curbstones” (46). Pandora’s own knowledge of letters, words, and “Old English” allows her to “[giggle] uncharitably” when she sees a “small child, who can’t read Old English” playing in a “generous stone sandbox, plaqued with a dog’s profile” and the words “Thorvald’s Comfort Station” in Old English font. And it seems to be a combination of Pandora and the narrator who offers the observation that “Here is the promised respite for canines-on-leashes who did not, as repeatedly beseeched” in Old English font “Befoul the Promenade” (see Figure 3).

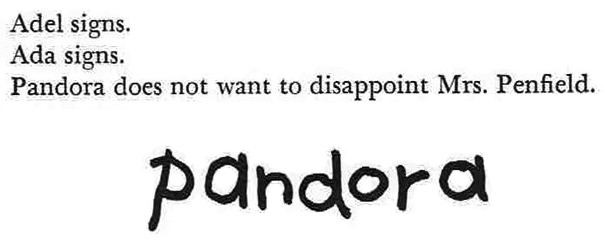

23 The emphasis on the struggle between the language of adult and child, printed and oral, authoritative and imaginative, provides insight into how language forms the writer and how the Bildungsroman can, by necessity, become the Künstlerroman for those who write themselves out of positions of marginalization and victimization. In the oppressive and small world inhabited by Pandora Gothic, the language of the mind and imagination counteracts the forcefully literal words of family members, peers, and figures of authority. At six years of age, Pandora makes her mark when she signs the pledge for Mrs. Penfield not to drink, smoke, or take “God’s name in Vain” (94) (see Figure 4).

Unlike Adel’s and Ada’s implied straightforward signing, Pandora’s signing clears a space for herself on the pink pledge card “engraved in gold” (94) as well as on the page of the novel. Even at eight years of age when the novel ends, it is apparent that Pandora will need to continue to clear a space in order to articulate the placement of her words and body in a world that attempts to shut away her exuberance in small spaces, contain her sharp intellect, and silence her imaginative ideas and thoughts.

24 Pandora’s adept use of language reveals an equally perceptive understanding of her body as displayed after she and Arlene view a showing of Baby Scotty’s penis, which they judge to be “not much” (55) compared with the earlier offering of the flasher in the park. In response to Arlene’s observation that had Pandora’s brother, Baby Victor, lived, “he would have shown [Pandora’s] thing” to others (56), Pandora confidently explains the advantage of her vagina over a penis: “I have ‘insides,’ which are neater” (56). Her diction exhibits a comfortable knowledge of both language and self. She does not see absence in her girlhood body, but rather advantageous presence in the inner rather than outer arrangement, which grants her privacy. Exposure and threats of public exposure by and of males are greeted by girlhood with derision and denigration to counteract fear and vulnerability, but the relief of not possessing a “thing” that can be displayed, judged, and ridiculed is real. The word “neater” refers to the simple and agreeable inner arrangement without embellishment, but also carries the colloquial meaning of “better.” Parts of Pandora that are publicly visible and displayed, such as her ringlets and wart, are at risk of being gazed at, touched, and cut off, but her sexuality, internal and private in her view, contributes to the gradual development of inner substance. The earlier slap from Adelaide for Pandora’s attempt to touch her vagina is counteracted here by Pandora’s concise, accurate, and confident words of ownership and control. Her articulate use of language both results in and reflects a familiarity with her physical self, which is repeatedly challenged and undermined, but also reinforced, by instances and threats of male exposure. Pandora fights back with increasing determination, and as her language acquires articulate sophistication, the firm confidence of her resistance increases.

25 Hélène Cixous’s “The Laugh of the Medusa” (1975), published in English in 1976, four years after Pandora, refers to the young female body in ways that remind readers of the issues under discussion during the decade in which Pandora was published. Cixous’s observation about women “returning” locates the return in childhood:

The seething body identified by Cixous is an integral part of Pandora, who uses seething to establish presence and resistance. As Pandora masters language, she begins to grow into her body, filling it with substance and encouraging it to take up space. It is, however, a long and interrupted process, often involving regressive instances of Pandora making herself small rather than large as she seeks out hiding places or is pushed into them by others. A pattern emerges in Pandora’s childhood whereby her body is stuffed with sweet treats forced upon her, offered to her, or greedily taken by her. This engorgement is followed by a retreat to a small space often accompanied by an involuntary purging of the body. A horrific incident with the breadman initiates Pandora into this repetitive stuffing and emptying of the body. While being sexually assaulted by the breadman after eating tarts and eclairs he has thrust upon her, Pandora makes herself small and “very still, the way a small animal, cornered in a bush, humbly assumes the posture of death as a sop to death” (71). After running away from the breadman’s wagon in the “stand of slippery elms” near the railway track away from the road, Pandora “hides in her cubbyhole . . . in the dark . . . in a wedge of cheese, as black as fear, where the floor meets the sky” (72). The wedge of cheese brings in food and connotations of the folk tale, nursery rhyme, and playground game, but the yellow-orange of the wedge is permeated with blackness.11 Pandora herself is wedged between many places, but most significantly at this point between play and danger and between the outdoor world of the breadman and the indoor world of her family, both of which bring her shame and fear. She weeps and is heartbroken when she looks at “her naked body in her dresser-mirror” (72). This mirror stage and period of heartbreak, however, is one to be overcome rather than given into. Temporarily broken, Pandora pulls herself together and continues to seethe in order to survive, which depends on the acquisition of language — on reaching a stage where she is able to name her fear and shame.

26 The same cubbyhole provides refuge after Pandora has stuffed herself with chocolates offered by Great Aunt Gertie and is reprimanded by Aunt Estelle for appearing to be unfeeling about Grannie Cragg’s death. Pandora walks “up the attic stairs, through her bedroom, into the narrowest cubbyhole, back, back, back . . . crawling now, to that darkest wedge where the splintery floor meets the wallpaper sky.” Again the word wedge appears, the sky identified here as the wallpaper sky rather than the real one. Once she is positioned within the darkest wedge, “the cold white egg inside Pandora bursts” and she “vomits fear and Smiles’n’ Ha ha chocolates” (108). This stuffing of the body with sweetness followed by an involuntarily purging becomes a pattern as Pandora takes in the temptations offered to her by others, greeting such gestures with open hope and good will, only to be undermined and betrayed by both the giver and, more devastatingly, by her own body.

27 Pandora’s foreboding anticipation of Grannie Cragg’s death occurs during nocturnal turmoils and nightmares after she has “stuff[ed] her mouth with various meringues, macaroons, peanutbutter cookies” (100) filched from the meeting of the Duchess of Gloucester Chapter of the Mill City Home Front Auxiliary hosted by Adelaide. The desperate stuffing is an attempt on Pandora’s part to fill her body to capacity in order to prevent anybody else from doing it for her. The purging in this case consists of vowels, which Pandora, through a reading lesson, had tried to stuff into Grannie Cragg earlier. During the night she hears the vowels being vomited from Grannie Cragg’s snoring mouth — “AAaaayyeeeeeiiiioooouuuuuuu. . . .” — prior to them attacking Pandora in her bed and eventually taking the form of “Nazi Vowels” as the assault increases in intensity. Individual vowels, based on shape, become cleat boots, ropes, whips, and horseshoes (100). The vowels, detached parts of language that must be combined with consonants in order to make words, sentences, and meaning, lack veracity and wholeness on their own just as the fancy cookies by themselves fail to provide healthy nourishment. Vowels, which Grannie Cragg explained to Pandora were useless to her in her illiterate old age, are the basis of Pandora’s world, requiring her to recover following the nightmare attack in order to continue to control, master, and combine letters and sounds, vowels and consonants, on which meaning and her survival depend. The destructive capacity of language is recognized and quelled by Pandora.

28 Parts of Pandora’s body, like the stray vowels, need to be brought under control. Her “long, golden hair” (116), for example, which is particularly enticing, sets her apart from others, particularly from Adel-Ada, who “only have skinny brown braids you can see through” (14). Adelaide attempts to tame Pandora’s Rapunzel-like hair by braiding it as she does her own and Adel-Ada’s. Pandora is humiliated by the act, during which her mother’s “bone fingers part, plait, bind and wind her hair, as if it had no more personal destiny than the bits of string she twists so endlessly into doilies,” and she quickly dismantles her braided halo as she escapes outside and plays at being Pandora Palomino, Pandora Daedalus, and Pandora Medusa in what the narrator deems to be “acts of survival” rather than “capricious acts of disobedience” (116). Pandora’s hair attracts unwanted attention, ranging in her mind from the attention of imagined Nazis, who “will cut off [her] curls and make whips of them” (14) to the fascination of “Perfect Strangers” who cannot resist fondling her blond curls (116). The attempt to tame and control through braiding, however, is contradicted in a confusing way for Pandora through a weekly ritual during which her hair is “spun into rag chrysalises every Saturday night,” turning her into “Shirley butterfly Temple every Sunday morning” (116). The golden tresses are deliberately made more enticing, perversely encouraging the touch that strangers cannot seem to resist.

29 When Pandora ends up with “Fleers Double Bubble gum matted behind her left ear” (139), she loses a portion of her hair in a violent and bloody episode. Referred to as a “tumour,” the gum-entangled hair is taken care of by the barber, but as “Pandora yanks her head away,” the “razor gashes her ear. Blood spurts” (139). The spurting, spattering, and running blood shocks Pandora until she “feels herself pitching forward, through the thin crust of Time and Place that other people call reality” (139). Later at home, Pandora, in a desperate but determined attempt to recover the part of her that has been so violently and unjustly taken, tries to glue the hair back on. Looking in the mirror at her “cropped head” and “spindly body,” she wants to die (142). Resilient, however, Pandora continues to fill her body with the strong emotions Adelaide has accused her of lacking. She articulates into wholeness that which has been pulled apart; in resistance against violence and threats of violence, she connects what is fragmented and fills what is empty. The italicized stories in her mind and imagination do not separate her from her body, but encourage her to fill it with feelings, the existence of which others have denied or have tried to force out of her. She notes, for example, that her mother and father “have squeezed out [Adel-Ada’s] juices and that is why they’re so pale” (54); Pandora is determined not to let herself be drained in this way. The qualities that set Pandora apart — she is identified by Barclay as “imaginative and sensitive as well as brave, independent, pretty and clever” (109) — contribute to both her vulnerability and her strength. Although her daring behaviour puts her in positions in which her body is filled and purged, she does not allow others to drain her and she is far from pale or empty.

30 The wart on Pandora’s thumb, like the tumourous clump of hair, is a grotesque lump which threatens her body with abnormality. Like the boy’s “thing” as opposed to the girl’s neat insides, the wart draws attention to itself as an appendage. Its miraculous disappearance is a relief. Swellings felt in the gut, however, are more difficult to quell. The rats that Pandora feels rising inside herself as she witnesses horrific injustices and scapegoating in her grade two class are darker, more devastating, and more difficult to release than the roiling sweets and the breakable egg she held within her body at a younger age. When Pandora understands the racism and hate at work in her school and society, she “can’t get her rats to go back into their holes. She feels them forcing their way, like vomit, up her throat. She hears them clawing and squealing inside her skull” (223-24). They move from the gut to the mind. The rats are banished in a fairy-tale-like ending, which sees Pandora flying above the schoolyard in a scenario of “it’s a bird, it’s a plane, it’s Pandora” (237). And almost miraculously Lyle and Adelaide are in a position to offer Pandora education, which translates into “Another Sort of Life” (252), reminiscent of “the change coming . . . in the lives of girls and women” (146) taken up by Del Jordan at the end of Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women (1971). Pandora’s own language, narrative, and imagination, supported by the fairy godmother/narrator lift her in super-hero fashion above the vomiting body wedged into small spaces in the family home, but it is actually Grandma Pearl’s money that will eventually and permanently take Pandora away from Oriental Avenue, making possible the transformation into the new Eve or the subversive new woman identified by Tostevin and Irvine.

31 If, as Carol J. Singley claims in “Female Language, Body and Self,” “women’s relationship to language is shaped by the female body; by the cultural roles women play as wife, daughter, and mother; and by the narrative forms which inscribe these roles” (5), then it is important to look closely at the girlhood body, not merely as a formative stage but as a central element in this process. Fraser urges readers to do so. The compressed space allotted to girlhood within fictional texts and society results from assumptions that the girl lacks substance, but at the same time reveals a fear of what could be exposed if the girl were given more space. Such assumptions and fears are at the heart of Fraser’s Pandora. The explosion of girlhoods in twenty-first-century Canadian fiction indicates that the figure and genre are no longer wedged into small corners. It is important to return to earlier work that anticipated and now converses with the recent proliferation of literary girlhoods, and Fraser’s Pandora is an obvious place to start. In this novel, girlhood in the 1940s as remembered and written in the 1970s has much to offer, not only to the recovery of Canadian women’s writing from the 1970s, but to the interdisciplinary discussions of girlhood currently taking place. It is through the relationship between the girlhood body and language that the 1972 character and novel move into startlingly contemporary conversations with the twenty-first-century interdisciplinary field of Girlhood Studies, suggesting one of the many ways in which Pandora, as Tostevin proposed thirty years ago, was “ahead of its time.”