Articles

Putting Ann-Marie MacDonald in the Closet:

The Reception of Adult Onset

1 In a review of Ann-Marie MacDonald’s novel Adult Onset, Zoe Whittall draws attention to how literature by queer authors circulates in the Canadian marketplace. Drawing on R.M. Vaughn’s concept of the “lavender ceiling,” in other words the marketplace limits for authors “who write honestly about contemporary gay life,” Whittall wonders how MacDonald’s novel will be received, optimistically stating that “I have often thought that if any author could change Canadian publishing’s reticence to promote present-day queer stories, it would be Ann-Marie MacDonald.” This optimism, however, does not appear to have been answered. Adult Onset did not come close to the level of international success of Fall on Your Knees or The Way the Crow Flies, both “picked” for American book-club lists and translated far more extensively. Nor did the novel garner as much institutional recognition as the two previous novels with respect to high-profile Canadian and international literary awards. Finally — and likely related to Adult Onset’s comparatively lesser international success — the American edition of the novel was published not by Touchstone/Scribner’s/Simon and Schuster (Fall) or Harper Perennial (Way) but by the relatively smaller press Tin House Books. Even beyond the issue of sales and awards, though, Whittall’s assessment that Adult Onset will be read as a novel about “contemporary gay life” seems to be incorrect, at least insofar as the novel was marketed and received not as a queer story but as a domestic drama primarily about parenthood and the lasting trauma of child abuse.

2 As I argue, Adult Onset is largely a complex story of coming out, yet that story, for the most part, is not “read” by those marketing the novel and is thus made invisible. I explore the significance of how Adult Onset is circulated as a cultural object as well as how MacDonald anticipates potential blind spots in the novel’s reception via her self-conscious use of intertexuality and in her thematic exploration of the way that authorial bodies and/or bodies of work circulate. I consider the elision of Adult Onset as a queer work in relation to notions of Canadian literary celebrity and what Eve Sedgwick refers to in Epistemology of the Closet as multiple ignorances, exploring how MacDonald’s “coming out” novel appears to have troubled mainstream expectations about the appropriately Canadian queer voice.

3 It might appear odd to suggest, as I do here, that MacDonald’s status as a queer Canadian writer is anything but a settled subject or that it might trouble any reader of her work that Adult Onset would contain the exploration of uniquely queer experience. At least since the success of MacDonald’s play Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet), first produced by Nightwood Theatre in 1988 and published in 1990, and even more so once Fall on Your Knees became an international bestseller, MacDonald herself has been unambiguously “out.” As she noted to interviewer H.J. Kirchoff in 1995, just before the release of Fall on Your Knees, “I do consider it important for me to be out. . . . It’s different for everybody, and there are a lot of grey areas. But for me, it’s 12-year-old news. Most of the world doesn’t have the advantages I do. People who come out can lose jobs, families, friends. I have the luxury of forgetting about it” (“Unstoppable”). Added to the matter of her identity is the fact that most of her work includes queer characters, from the bi-curious Constance and Juliet in Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet); to Jayne Fine, the closeted lesbian in The Attic, the Pearls, and Three Fine Girls; to Kathleen and Rose in Fall on Your Knees; to Madeleine McCarthy in The Way the Crow Flies; to Tyrone and Alberta in Anything that Moves; and so on. What I am interested in, however, is the way Adult Onset reflects MacDonald’s cognizance of how queerness has become mainstreamed. In the 1996 study Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay and Lesbian Liberation, Urvashi Vaid notes the “limits of mainstreaming,” whereby the “pragmatism” of a seeming queer liberation based upon “winning mainstream tolerance” produces only the “trappings of full equality” (3-4). Building upon Vaid’s work — as well as on the work of Alexandra Chasin, Lisa Duggan, and Katherine Sender — Jane Ward argues in the 2008 study Respectably Queer: Diversity Culture in LGBT Activist Organizations that mainstream queer political practices are strongly influenced by “corporate” or “neoliberal” cultures:

Key here is the idea that queer identity is defined and reiterated in ways comprehensible and palatable to a mainstream, heteronormative consuming public, which — as the arbiter of “tolerance” (Vaid 3) — becomes the gatekeeper of acceptably queer behaviour.

4 Even more relevant to the particular case of queer “mainstreaming” and Ann-Marie MacDonald is Tim McCaskell’s work in Queer Progress: From Homophobia to Homonationalism, which considers these issues within a Canadian context. After chronicling and reflecting on his forty-year history of queer activism, including central work with the Public Action Committee of the Right to Privacy Committee, with AIDS ACTION NOW, and with Queers Against Israeli Apartheid, McCaskell considers the current relationship between the Canadian national imaginary and queerness:

I argue that MacDonald’s “anxious” awareness of this “Faustian bargain” is visible in the tension between the coming out story that frames Adult Onset and the novel’s representations of domestic dramas. As I suggest, Sedgwick’s notion of multiple ignorances offers a useful framework for exploring the intersection between the circulation of Adult Onset as a cultural object and the way that queer expression is policed, often via rhetoric pitched as well meaning and “liberal” (McCaskell 456). Thus, both the novel and its circulation provide opportunities to examine mechanisms for the strategic forgetting of queer experiences, especially those that cannot be marketed as empowering within Canada’s tolerating, neoliberal, homonational framework.

“When Is the Book Coming Out?”: MacDonald and Literary Celebrity

5 When I suggest that Adult Onset is “largely” or in actuality a coming out story, I am not proposing that this element is in any way buried in the novel, similar to how both Fall on Your Knees and The Way the Crow Flies explore secret and buried histories, what I call “twin tales” or “the power of stories both to bring into being and to controvert various possible realities” (161). For example, in my reading of Fall on Your Knees, I argue that Frances’s several stories about Ambrose, Lily’s drowned twin, allow both sisters to recast the evidence of their father’s sexual abuse as a fairy tale; later, when Aloysius/Anthony is born, he is interpreted as both a resurrection of Lily’s drowned twin and the symbolic son of Kathleen and Rose (173). To read Adult Onset as a coming out story requires no such speculative fireworks, for this topic is plainly and regularly articulated throughout the book. In The Way the Crow Flies, Madeleine’s coming out story is mentioned three times over the course of a novel more than seven hundred pages long, including a scene in which Madeleine briefly describes her parents’ reactions to references to her partner, Christine: “[My mother will] throw a fit. . . . [I]t’s all pointy and shrill and hysterical. My dad, on the other hand, takes us out for lunch when he comes to Toronto” (576). Conversely, on page 2 of Adult Onset, the protagonist — Mary Rose MacKinnon, or Mister, as she is called by family and friends — receives an email from her father with the subject line “Some things really do get batter . . . ” (2). The spelling error notwithstanding, the content of the email makes it clear that her father is referring favourably to her and her wife Hilary’s participation in an “It Gets Better” project. The opening reference to the email, in a scene extending well into the “Monday” section of the seven-part novel as Mary Rose tries and fails to respond to her father’s cheery missive, forms the opening of Adult Onset’s conceptual frame. The novel ends with her delayed response, thus enclosing all of the action within the contemporary context of an adult daughter’s coming to terms with her parents’ coming to terms with her queer identity. Beyond this conceptual frame, other references to the coming out story of Mary Rose in Adult Onset include her dawning awareness as a girl that she had “crushes” on girls that had to be hidden; how her brother, Andy-Patrick, helped her by accepting her as a lesbian; as well as her often volatile conversations with Hilary, in part about the long-term effects of a painful coming out.

6 Even more significantly, at several points in the novel, the narrative focuses on the horrific treatment of Mary Rose, especially by her mother, Dolly, when she comes out, culminating in a description of Mary Rose sitting at her parents’ kitchen table and being told by Dolly “I’d rather you were a murderer,” “I’d rather you were burnt at the stake,” “I’d rather you had cancer” (205). Most of the time Mary Rose likes to tell herself that, had it been his individual choice, her father would have been more supportive, especially given his seeming encouragement of her childhood challenges to gender norms: “Do it your way, Mister” (188). Thus, Duncan MacKinnon of Adult Onset seems to be an echo of Jack McCarthy in The Way the Crow Flies: a father who will take his lesbian daughter and her partner out for lunch. The penultimate scene of Adult Onset, however, details a phone conversation that Mary Rose once had with Duncan on the matter of his refusal to accept her queer identity. As she begs her father “please, please, please come and see me in my home,” he responds “calmly” with a litany of repudiation: “That’s not a home,” “You let yourself go,” “You’ve turned your back on us,” “The Mary Rose I know does not choose to live the way you are living now,” “You are sick,” “If you were a drug addict, I would not be doing my job as a father by giving you more drugs when you beg for them” (378-80). Finally, for those attentive to MacDonald’s status as an unrepentant punster, the subplot of Mary Rose’s writer’s block offers a wonderful if dark joke: whenever Mary Rose encounters fans of the first two instalments of her YA trilogy Otherwhere, they inevitably ask, “When’s the book coming out?” (134).

7 As should be clear even from the minimal comparisons of MacDonald’s three novels mentioned above, her work is both highly intertextual and self-referential. In her plays and novels, common themes and images, for example references to secret twins and “other” children, “miraculous” pregnancies and stillbirths, limbo, family trees, the Gothic, detective work, military families, familial abuse, complex parental figures, and so on are persistently revisited. The figure of MacDonald herself — military brat, East Coast transplant to Toronto, multiethnic, Catholic, queer artist — is explored via refracted examinations of familial, national, and sexual histories.1 As MacDonald suggested in a 2014 interview with Matt Galloway, she thinks of her three novels as linked and that, in progressively setting her books closer and closer to the present day, she has been “sneaking up on [her] self” (“Interview” 21:02).2 The interplay of these two characteristics — intertextuality and self-referentiality — in her work shows her interest in thinking through both the circulation of a body of work and the circulation of the body of its author. In Adult Onset, MacDonald draws attention to these paired topics, for example via the intertextual Otherwhere subplot, which includes excerpts from the first novel in the trilogy, in which a girl, with a fabulous dad, learns the truth about her lost twin brother. The figure of MacDonald is referenced in scenes depicting interactions between Mary Rose and her devoted readers. In one scene, a fan approaches the author in a Starbucks, asks for a selfie, and then informs her that she has misinterpreted an element of her own novel (230). In another, two nurses, for no easily apparent reason, continue to “swish” into and out of the examination room during an appointment that Mary Rose has with a gynecologist and then, “as she is mopping up,” hand her books to sign (107-08). This hyperbolic image of the author’s body as circulating and open to public scrutiny is echoed, more subtly, in a scene following the pelvic exam, when she is biking back toward her home: “She lets go of the handlebars and relaxes, surfing the speed bumps through the Annex with its big old Victorian houses. Someone in a Volvo drives by, it looks like Margaret Atwood. It is Margaret Atwood” (137). This scene implicitly asks how do we make a distinction between the figure who “is” Atwood (here an individual body) and the figure who “looks like” Atwood (here a name associated with a set of expectations about well-known authors)? Is the Margaret Atwood who circulates through the Toronto Annex in her Volvo the same Margaret Atwood whose authorial persona circulates within the institution of Canadian literary studies and whose name adorns the book Payback, which, toward the end of Adult Onset, Mary Rose buys a copy of for her father? These two references to Atwood — both as an individual body and as a Canadian institution3 — reveal MacDonald’s self-referential awareness of the link between the circulating authorial body and the notion of literary celebrity.

8 As P. David Marshall notes in his foreword to the essay collection Celebrity Cultures in Canada, “The production of public visibility in Canada has had its own patterns that are related to a very intriguing manufacturing of culture” (vii). His use of the term “visibility” is particularly significant in terms of how recent studies of Canadian celebrity, especially literary celebrity, can be linked with the concept of coming out or, as I discuss below, Sedgwick’s claim that, for the queer community, the closet is a “shaping presence,” whereby “every encounter with a new [person or group] . . . erects new closets whose fraught and characteristic laws of optics and physics exact . . . new surveys, new calculations, new draughts and requisitions of secrecy and disclosure” (68). In her own study Literary Celebrity in Canada, Lorraine York points out a peculiar paradox of this sort of celebrity: although writing is an activity that one pursues “alone,” the activity associated with inhabiting the role of the “aspiring” or “successful author” occurs in public, giving rise to a “tension between the writer as a public and a private agent” (13). Such tensions, York argues, become even more fraught within the Canadian context as “we continue, as Canadians, to cling to our belief that there is something different — often something more simple, modest, or ennobling — about our approach to celebrity”; further, because “Canadians and Canadian women in particular . . . are more modest about their fame,” they are popularly viewed as “more authentic and unspoiled as celebrities” (168). For the queer Canadian author, however, the conceptually paired and mythologized concepts of “modesty” and “authenticity” produce a potentially incommensurate double bind. As my reading of Sedgwick’s theorizing of multiple ignorances shows, one cannot be both modest and out, and one cannot be both authentic and closeted. York notes that “In some cases of literary celebrity I discern a . . . sexualized desire for details of the authors’ private lives, particularly where authors are socially marked, for whatever reason, as exotic or transgressive” (14). Queer identities and queer relationships to the closet, Sedgwick argues, are discursively determined to be a matter of “public concern” (70). Just as Mary Rose in Adult Onset, after being surveilled during a pelvic exam, moves through Toronto while trying to “navigate . . . the crush of pedestrians” (133), so too MacDonald, as a “transgressive” literary celebrity, must negotiate her status as a private/ public agent.

Closeting MacDonald: Marketing Adult Onset and the Command of Ignorance

9 MacDonald’s implicit queries about the potential for intrusive readings and misreadings of the author’s circulating body offer a prescient prologue to an analysis of how the cultural object Adult Onset (specifically the 2015 Canadian paperback edition) was circulated or how it was marketed by Vintage Canada (a division of Random House of Canada, part of the Penguin Random House Company). The paratext for this edition is fairly standard, with references to the novel’s status as a national bestseller, and to the author’s other novels, on the front cover, highlighted quotations from important reviews on the back cover, and twenty excerpts from reviews and notices on pages i-iii. A scan of these twenty chosen excerpts, in particular those that include some description of the novel’s content rather than just evaluations (e.g., “masterpiece,” “big, troubling, and brave,” “stunning and powerful”), shows a number of recurring terms: “parents” or “parenting” (seven times), “domestic” (three times), “history” or “the past” (three times), “modern life” (two times), and “families” (two times). Also, the terms “abuse” and “trauma” are used once each (i-iii).

10 Not a single one of the twenty excerpts from reviews and notices uses the term “queer” or “gay” or “lesbian,” or the phrase “coming out,” even when the original review from which the excerpt is taken does read Adult Onset as a novel, at least in part, about queer experience. For example, the paratext uses a quotation from Brian Bethune’s review of the book, originally published in Maclean’s. The review begins with two paragraphs about MacDonald’s discussion at a 2014 World Pride event about “a rage risen from the depths of repression, triggered by a loving, accepting message from parents who, decades earlier, had responded to her lesbianism with, ‘I wish you had cancer’” (Bethune). The excerpt chosen for the paratext, however, is from the next paragraph in Bethune’s review, which begins “There is barely a playing card’s width between life and art in [Adult Onset,] an intricate, gripping novel that is also a master class in turning the personal into the universal through art” (Bethune; Adult Onset ii). Even more problematic in its work to elide the matter of Adult Onset as an explicitly queer novel about explicitly queer experience is the use of a relatively long excerpt from Whittall’s review, which begins with this quotation: “Adult Onset . . . transforms from an ordinary housewife domestic-saga-with-a-twist to a story that has never been written before. . . . It’s brave for any parent to write about anger” (Adult Onset iii). In the original review, published in The Walrus, the paragraph from which the first grammatically awkward “sentence” of the excerpt is lifted begins thus: “Where Adult Onset truly transforms from an ordinary housewife domestic-saga-with-a-twist to a story that has never been written before is when it gets to the heart of the trauma of parental abandonment after coming out, and its lifelong effects” (Whittall). Whittall then devotes three paragraphs (about a third of the review section of her essay) to the subject of the coming out story in Adult Onset before starting her final paragraph with the phrase “It’s brave for any parent to write about anger.” It is this paragraph — the one that does not specifically draw attention to either MacDonald’s status as a queer writer or to the coming out story in the novel — that is quoted in full in the paratext. Thus, first, the elision does the work of pitching the text as a domestic novel aimed at a specific demographic of readers interested in novels about “anyone struggling to raise kids in an age of perfect parenting” (Whittall; Adult Onset iii). Second, and more troublingly, the elisions in the paratext are part of a rhetorical field insinuating that the coming out story in Adult Onset is not just “secondary” but can even remain unread, can be closeted.

11 Both Bethune and Whittall draw attention to rage in their comments on the novel, and the subject of rage can be linked with what I am calling the closeting of Ann-Marie MacDonald. Here I am working specifically with some of Sedgwick’s thinking in Epistemology of the Closet, in particular her discussion of the power dynamics of ignorance. Sedgwick, seeking to unpack the binary of knowledge/ignorance, states that “the fact that silence is rendered as pointed and performative as speech, in relations around the closet, depends on and highlights more broadly the fact that ignorance is as potent and as multiple a thing there as is knowledge” (4; emphasis added). Reading Sedgwick, I comprehend three uses of ignorance relevant to an analysis of Adult Onset, both as a novel and as a cultural object. First, ignorance is “sentimental[ly]” understood as “originary, passive innocence” (7), as in the phrase “We didn’t know.” For the most part, Adult Onset works through the insidiousness of this sort of ignorance via its representation of physical abuse, whereby Duncan MacKinnon clings to his rationalization for not “seeing” his wife’s abuse or his child’s pain: “No one thought your arm could possibly be broken” (380). Arguably, also, the revisionist family history that both Duncan and Dolly engage in, epitomized by the cheery and proud email from Duncan about the “It Gets Better” campaign, depends on their expedient embracing of the progressive, “mainstreamed” structure of the ignorance-as-innocence scheme, via which they now get to bask in their status as newly enlightened and tolerant. In particular, the representation of Dolly, who, at eighty-one years old, charms and invites hospitality from the gay barista at a Starbucks, exposes how ignorance-as-innocence causes harm: when Mary Rose raises the subject of Dolly’s changed attitude toward queer lives, Dolly looks “perplexed” (253), apparently failing to recall the years when she cruelly berated her daughter. Mary Rose is at once revisited by the effects of the original trauma and the trauma of confronting ignorance-as-innocence: “This café table was a world away from the kitchen table of yore, and yet she was still . . . anaesthetized. There must be considerable emotion collecting within her somewhere — as with fluids in a corpse. ‘You wouldn’t set foot in my home. Remember?’ She felt like she was lying. It wasn’t that the words she was saying were untrue; it was the fact of her speaking them at all” (253). At the same time, Mary Rose feels guilty about “dredging up bad stuff, torturing Dolly over a transgression” (257), as the queer subject now becomes responsible for causing pain to the newly tolerant person.

12 Thus, a second use of ignorance is wilful ignorance, the “command of . . . ignorance” (Sedgwick 7), as in the phrase “We don’t want to know” or the even more subtle and brutal “What happens in the bedroom is nobody’s business.”4 In this deployment of ignorance, queer subjects are made responsible for the “management of information” (70) about their sexuality as well as for whatever deleterious effects such information might have on heterosexual subjects (e.g., children, homophobic men, orthodox religious people, or the tolerating “mainstream”). In Adult Onset, during her agonizing phone conversation with her father, Mary Rose begins by pleading with him to visit her: “I’m begging you Dad, please, please, please come and see me in my home” (377; emphasis added). His refusal is ontological, for he asserts not that “I won’t come to see you in your home” but that “That’s not a home” (378). When Mary Rose declares “You’re saying you hate me!” her father responds “I’m not saying that to you. That is what you are saying to me” (378). Here Duncan makes his daughter responsible for his pain, a pain that he claims she causes not by being queer but by asking to be seen as queer: as he puts it in terms familiar to orthodox religious discourse, “Being homosexual is not wrong. Practising homosexuality is” (380). Also significant is the way in which the cultural object Adult Onset was subject to the command of ignorance, whereby the marketing team at Penguin Random House Canada simply edited out references to the queer bits of the novel from reviews, as if disclosing the novel as queer was deemed “a matter of public concern” (Sedgwick 70) and as if the possible effects of a queer novel on a heterosexual reading public had to be taken into account. The elision of references to queer content in the paratext of Adult Onset is an invitation to readers, ironically, simply not to see the novel’s coming out story, to remain wilfully ignorant that this story, which forms the conceptual frame of the novel, is asking to be seen.

13 A third use of ignorance that Sedgwick’s work considers, one implicit in the other uses of ignorance that I have tried to unpack, is ignorance as performative, as in “Our ignorance is constitutive; it makes you what you are.” The narrative of Adult Onset and the function of the novel as a cultural object become collapsed via MacDonald’s punning use of the phrase “When is the book coming out?” Implicit in this phrase, repeated by Mary Rose’s devoted readers, are larger questions: “When should coming out occur? When is it safe?” As Sedgwick explains, part of the urgent impetus for writing Epistemology of the Closet was “the increasingly homophobic atmosphere of public discourse since 1985” (21), a period when public frenzy about AIDS reached a fever pitch and the “homosexual panic” defence was considered to be a legitimate justification for gay bashing (19). Conversely, Whittall’s discussion of the lavender ceiling in her review of Adult Onset, a novel published in 2014, comprises a hope that the answer to those larger questions is “Now. Now it is safe.” In the novel, however, MacDonald explores the issues of timing, the coming out story, and performative ignorance by drawing attention to how Mary Rose’s parents make use of images related to illness and addiction (“I’d rather you had cancer” and “If you were a drug addict, I would not be doing my job as a father by giving you more drugs when you beg for them”). As part of her exploration of the idea of cultural constructs and performativity, Sedgwick considers medical discourse, in particular the “medicalized dream of preventing gay bodies . . . [and] of a culture’s desire that gay people not be, [in which] there is no unthreatened, unthreatening conceptual home for the concept of gay origins” (43). In other words, Sedgwick suggests, if the closet exists, if the queer subject must persistently negotiate the act of disclosure, then there is no such thing as a safe time for coming out.

14 Sedgwick’s use of the phrase “medicalized dream of preventing gay bodies” sums up discourse that considers homosexuality against a variety “of biologically based ‘explanations’ for deviant behaviour” (43) and that implicitly or explicitly proposes a biological cure for such deviancy. In The Way the Crow Flies, MacDonald briefly raises the “explanations” trope. In a scene in which Madeleine is discussing with her therapist being sexually abused by her grade four teacher, she resists the idea of telling her mother, fearing that her mother will latch on to the abuse as an explanation for her being a lesbian: “She’d — she’ll say, ‘So that’s why you’re the way you are’” (615). Forty pages of text later, when Madeleine does tell her mother about the abuse, the response is “Oh Madeleine . . . is that why you are the way you are?” (654). In Adult Onset, MacDonald works through the (il)logic of this trope more thoroughly, in such a way as to disclose the force of performative ignorance. Duncan tells Mary Rose “You are sick,” comparing her to a drug addict; he also accuses her of hiding her homosexuality from him so as to avoid a remedy: “If you had let us know early on that you had these tendencies, we would have been able to help you” (380). Mary Rose pushes her father to clarify: “If I had told you when I was a teenager and still living at home, you would have taken me to a psychiatrist? . . . And you would have had me hospitalized and treated. Electroshock, maybe” (380-81). When Duncan agrees, and again accuses Mary Rose of “hid[ing] your disorder from us,” she responds

A key issue that MacDonald explores in this scene is, again, that of timing, not only in terms of determining when it is safe to come out, but also in terms of determining, as Sedgwick puts it, “the concept of gay origins.”5 Mary Rose acknowledges that her own origin story is fuzzy and that at fourteen she “knew enough not to show anyone, not even myself, who I was.” Importantly, even for her, the queer subject, the idea of being a lesbian (“who I was”) is associated with “showing,” with an invitation to be seen, with the act of disclosure. As Sedgwick argues, coming out is not merely “reporting” (4); it is a speech act, a declaration of being (as if to be queer is not possible without having a relation to the closet).

15 Likewise, in Mary Rose’s relationship with her parents, and in her phone conversation with Duncan, the central point of contention is not her homosexuality per se but the function of her disclosure, her act of coming out and how it reflects on her parents, who deploy their performative ignorance (responding not “You are queer” but “You are sick”). Her disclosure is thus elided, like the elisions in the excerpted reviews, rejected in favour of a narrative in which homosexuality might have been avoided had Mary Rose disclosed it earlier (“If you had let us know early on that you had these tendencies, we would have been able to help you”). Sedgwick notes the untenable operation of the closet, whereby “the space for simply existing as a gay person . . . is in fact bayonetted through and through, from both sides, by the vectors of a disclosure at once compulsory and forbidden” (70). Duncan’s key grievance is that Mary Rose used the ignorance of her parents against them, disclosing her homosexuality only when it was too late to “help” her. Here disclosure is compulsory. His key directive, however, is that she return to the closet; as Duncan declares, “Being homosexual is not wrong. Practising homosexuality is.” Here disclosure is forbidden. So her parents’ ignorance is not only her fault but also her responsibility, a matter of public concern. One way in which Mary Rose resists her father’s performative ignorance (“You are sick”) is to refuse his use of the word help as a metonym for a father’s love or — to use Duncan’s term — a father’s “job.” She ends her discussion with her father by declaring, “I’m twenty-three and all you can do to me now is hate me.” Thus, MacDonald suggests that references to the idea of “helping” the queer subject not be queer, even via the most seemingly benign uses of the explanatory trope or the mainstream “it’s none of my business” pronouncements, constitute violence. Such enactments of well-meaning concern are simply a veil for performative, constitutive ignorance.

“She May Have Committed Herself to a Life in Which a Closet Is Just a Closet”: MacDonald’s Disappointed Fans

16 Expanding on his comment about the “public visibility” associated with celebrity culture, Marshall asserts that “Canadian cultural systems have used the celebration of the public individual as a technique to attract attention, organize cultural production, and maintain the interest of the audiences of the nation” (viii). In the case of the figure of MacDonald and the novel Adult Onset, the issues of “attract[ing] attention” and the “audiences of the nation” seem to be especially pertinent given what I am arguing is essentially a violent elision of queerness by Vintage Canada and given that the operation of knowledge/ignorance might be connected to what York calls the myth of the “modest” and “authentic” Canadian literary celebrity. In broaching the topic of national reception, it is interesting to consider briefly the distinct responses to Adult Onset by readers commenting on Amazon.com (twenty-three verified purchaser reviews)6 versus Amazon.ca (thirty-three verified purchaser reviews).7 In her examination of the circulation and reception of Fall on Your Knees, Danielle Fuller discusses the marketing of the 1996 novel in terms of its bridging a generic gap between “serious literary fiction” and the highly gendered “beach-bag blockbuster” (50), a feat epitomized when the novel was picked for Oprah’s Book Club. As I have suggested above, Adult Onset was marketed primarily as a domestic drama about parenting and the generational effects of trauma, which can be understood as a production choice once again to increase “the potential profitability of [a] novel as a genre that can attract a wide readership” (Fuller 50). As part of her analysis of the marketing and reception of Fall on Your Knees, Fuller considers how reviewers on Amazon are “self-conscious — even anxious — about their reading practices in relation to readers whom they perceive as possessing greater cultural authority” (52). Although the very limited data set of verified purchaser reviews is in no way conclusive, I argue that it is part of the same rhetorical field of well-meaning constitutive ignorance, whereby queer stories are subjected to the judgments of a tolerating, heteronormative public. Further, as even these limited comparative data show, the reception of MacDonald’s work reveals the workings of homonationalism or the way that the mainstreaming of appropriate or respectable queerness reflects the ideals of the imagined nation.

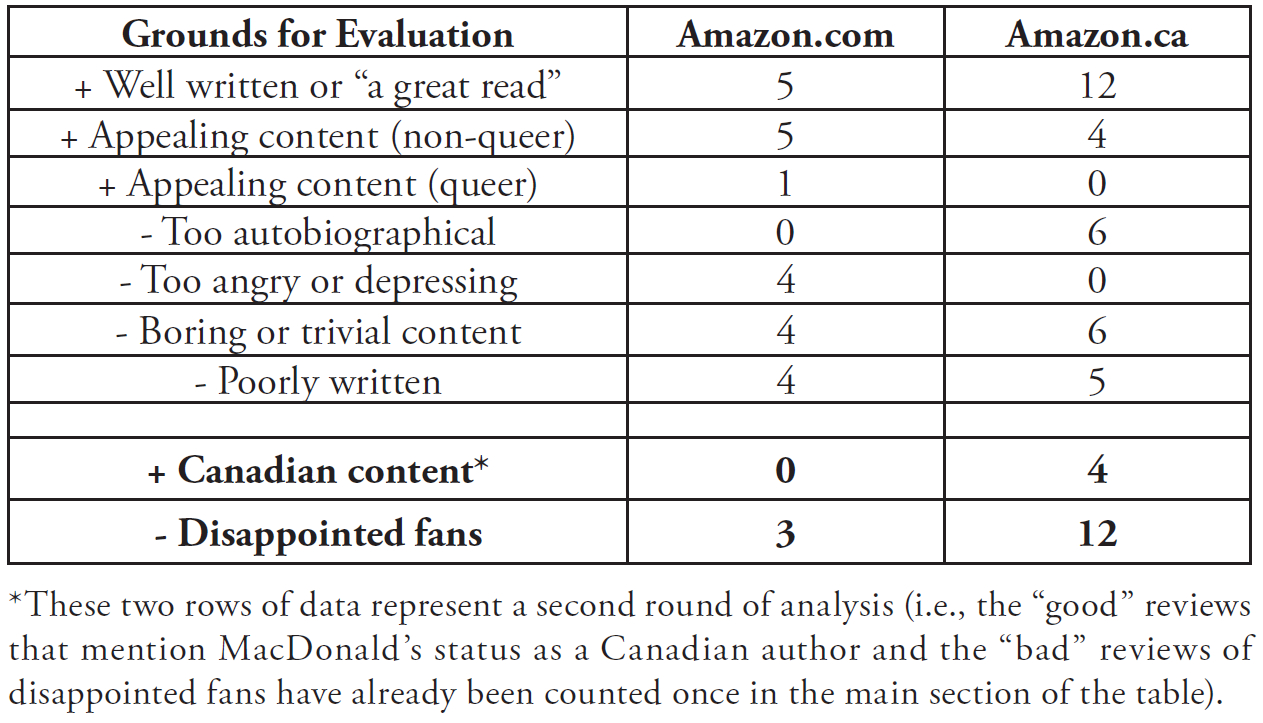

17 To a strikingly similar degree, readers on both sites are split in their evaluation of the book: of the comments on Amazon.com, eleven declare that the book is good, ten that the book is bad, and two that the book is of middling interest (“Amazon.com Comments”); similarly, of the comments on Amazon.ca, sixteen declare that the book is good, fifteen that the book is bad, and two that the book is of middling interest (“Amazon.ca Comments”). The differences in the responses emerge from an analysis of the stated grounds for readers’ evaluations, for better or worse, organized in Table 1.

Notable in this comparison is the difference between how Amazon.com and Amazon.ca reviewers identify what they do not find appealing: although a similar number of critical comments assert that the book is boring or contains trivial content, or is poorly written or confusing, Amazon.com readers are more likely to comment that the content seems to be angry or depressing, whereas Amazon.ca readers are more likely to criticize the book for being too autobiographical. Further, those giving bad reviews on Amazon.ca are far more likely to remark on their status as disappointed fans, sometimes in passionate terms. For example, one reviewer remarks that “I had waited so long for her to publish another book, my anticipation was high and I found this book disappointing”; another writes that “I loved her 2 other books. LOVED. To the point that whenever I see them in the local used book store, I buy them, and promptly give them away. I don’t feel the same about this one, other than the compulsion to give it away. I feel disloyal even writing this, but this novel cannot hold a candle to the previous 2” (“Amazon. ca Comments”). Use of the phrase “I feel disloyal” is telling, reflecting a common theme in the Amazon.ca reviews, both favourable and unfavourable, that MacDonald is especially tied to a Canadian readership, a national public concern. As per York’s reading of the peculiarly Canadian attitude toward literary celebrity, anything too autobiographical is not modest.

18 Although reviews by Amazon readers operate not as conclusive data points but as examples within a rhetorical field of multiple ignorances,8 it is significant that MacDonald’s insights into the subject of the author’s body (of work) and metafictional references to it in Adult Onset extend to the notion of a group of disappointed fans. (And perhaps ironically there is no evidence in any of the verified purchaser reviews that a reader recognized himself or herself in the various textual iterations of fans of Mary Rose’s Otherwhere series, who continually ask versions of the question “When is the third book coming out?”) After one such meeting between a fan and Mary Rose, the author “flees” and considers that

In this passage, Mary Rose/MacDonald implicitly acknowledges her previous two novels as generically delimited and therefore safely queer; “Narnia,” or YA fantasy, works as a metaphor for historical fiction, each of which is a “genre that can attract a wide readership” (Fuller 50). In her interview with Galloway, MacDonald also acknowledges that, though in all of her work she draws on her own experiences, in Adult Onset she dispensed with the accoutrements of historical fiction: “There’s no sets, lights, period costumes, props” (“Interview” 21:22). Also important in the novel’s metafictional moment is the working through of multiple ignorances as they relate to “fans” who now lay “claim” to the author’s body (of work). Mary Rose’s query “what if she attempts a return only to find the portal barred?” shows MacDonald’s prescience, for it coheres with the wilful and performative ignorances that emerge in the Amazon.ca reviews, whereby “too autobiographical” might be read as code for the commanding “we don’t want to know” and “disappointed” as code for the constitutive “this is not who you are.” Thus, the line “a closet is just a closet” is doubly ironic, for the performative ignorance of a reading public makes literal one metaphor (the closet as a magical portal), itself linked to another metaphor (the closet as a painful feature of queer identity). For the out queer writer, the notion of feeling like an “imposter” barred from belonging to her own queer experience seems to be an especially cruel iteration of performative ignorance.

19 In Pink Snow: Homotextual Possibilities in Canadian Fiction, Terry Goldie attempts a survey of the “homosexual tradition” (1) in Canadian literature.9 Quickly, however, he admits that his project primarily engages not in the enumeration of explicitly queer Canadian works but in a series of methodological principles for performing what he calls “homosexual read[ings]” (16), which he admits operate as a form of “outing” (4). In his formulation of what he calls “homotextual possibilities,” however, the figure most explicitly “outed” is the queer reader who reads homosexuality into a particular text: as Goldie puts it, “The homotextual is not what the homosexual writes but what the homosexual reads” (16). Importantly, for him, the concept of the homotextual is linked to the idea of “gay pride” (16): although he does not contend that “only homosexuals . . . can do homosexual readings” (14), he does assert that “my own need to find reflections of myself in what I read enfranchises both resistant and complicit readings” (15-16). These twinned concepts — resistance and complicity — are part of MacDonald’s metafictional rendition in Adult Onset of a coming out story, for the novel wrestles with how the existence of the closet persistently demands from the queer subject “new surveys, new calculations, new draughts and requisitions of secrecy or disclosure” (Sedgwick 68). On the one hand, MacDonald addresses the magnetism of complicity, a “Faustian bargain” and fantasy in which she accepts the identity of the only modestly transgressive, mainstream, Canadian literary celebrity, who writes wildly popular books for a market and public that would prefer queer readings of her works to be non-compulsory or at least containable within the generic category of historical fiction. On the other hand, Adult Onset is an act of resistance to the multiple ignorances inherent in the lavender ceiling as well as a gentle challenge to Goldie’s notion that homosexuals are those chiefly responsible for performing homotextual readings. As Mary Rose acknowledges, “Perhaps Hilary is right, she needs to start working again.” In this novel, MacDonald articulates — with increased transparency — two related ideas: that the existence of the closet does violence to queer individuals and that the erasure or elision or emptying out of queer narratives of the closet by the “tolerating” mainstream, via a series of innocent and wilful and performative ignorances, might do an even greater violence. As Mary Rose writes to her father in the final scene of Adult Onset, “Sometimes things need to get worse before they can get better” (384).

Notes