Articles

“A Scrap of the Savage”:

E. Pauline Johnson’s Canoeing Journalism

1 When E. Pauline Johnson (1861-1913) told the “girls” — the female readers of Outing — that they should give a “dash of the primitive” play “at least once a year,” she knew how hot and bothered men might be at the thought of “etiquetteless” women “quaffing . . . nature’s wines in the wilderness.” Johnson’s seemingly contradictory message, one that promotes women’s independence while titillating a male readership, shows a canny understanding of popular culture related to canoes and stereotypical conceptions of Indigenous peoples. While known for her poetry, Johnson was also a key figure in the canoe craze, a tide of canoeing popularity that surged in the 1870s and peaked in the 1920s. During the canoe craze, Americans and Canadians loved their canoes and made love in their canoes, and Johnson’s essays about canoeing demonstrate a manipulation of the stereotypical “Native” resonance linked to the canoe in popular culture. Johnson used those cultural associations to act as an independent New Woman and skirt the edges of traditional gender expectations.

2 Born in 1861 on the Six Nations Reserve near Brantford, Ontario, to George H.M. Johnson, a Mohawk Chief, and Emily S. Howells, a white Englishwoman, Johnson spent much of her youth canoeing on the Grand River. She began publishing poetry in Canadian periodicals in the 1880s, and after a well-received 1892 recitation of her “A Cry from and Indian Wife” in Toronto, Johnson began touring under her taken Mohawk name “Tekahionwake” as an “Iroquois Indian Poet-Entertainer” who read “her own poems of Red Indian Life and Legends” (Strong-Boag and Gerson 102-11).1 Johnson played with audience expectations, changing costume mid-show between “Native” regalia — one she patterned off an illustration of Longfellow’s Minnehaha — and an evening gown.2 And she pivoted between her identity as a Mohawk author and her position as a New Woman, as Strong-Boag and Gerson explain: “Pauline Johnson’s life and work suggest an implicit effort to reconcile and integrate the insights of Natives and New Women in a critique of the dominant race and gender politics of her day” (69). This reconciliation was complicated by Johnson’s need for income: “The time period in which Johnson lived and wrote, as well as her financial needs at the time, dictated certain limitations on her ability to address directly issues of concern for Native people” (Monture 91). Despite her self-styled “double” voice, readers of Johnson’s poetry were encouraged by critics and publishers to view her sexuality and independence as an aspect of her race: “Johnson’s reviewers almost uniformly constructed her as the erotic Other, the passionate poetess whose non-European heritage accounts for the unabashed sexuality of poems which are not, in themselves, explicitly Indian” (Strong-Boag and Gerson 145). Reflective of these struggles, critical discussion of Johnson has centered on the recovery of her neglected writing,3 her Indigenous-themed work and attempts to promote First Nations rights,4 her New Woman’s agenda,5 or her Canadian nationalism.6

3 This critical focus on Johnson’s control of her identity was also evident in contemporary discussions of her life and work. In his introduction to Johnson’s posthumously published The Shagganappi (1913), Ernest Thompson Seton compared her social and professional adaptability to her canoeing ability:

Though he admired Johnson, Seton clumsily characterizes her as a “shy Indian girl” even as he calls her a “world-woman.” Seton’s image of Johnson with “paddle poised” in the steering position (stern) of the canoe is apt, however, because in her canoe — literally or in her writing — Johnson proved adept at controlling her identity.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

4 In articles published between 1890 and 1897 in newspapers and magazines, some on the importance of women’s outdoor recreation, others on canoe clubs, and whole series on canoe-camping excursions, Johnson wrote about self-assured women who were competent, independent, and alluring.7 At the same time, she used her skills as a camper and paddler to deconstruct the identity of males around her. Beyond writing herself and her companions into the image of the New Woman, Johnson used the “Native” resonance of the canoe simultaneously to evoke a Canadian identity and the sense of the exotic Other. As Misao Dean notes, the canoe’s “very presence signals an attempt by a literary text to claim a place in a unified discourse of ‘nativeness,’ to situate itself as Canadian, yet it also evokes . . . ‘the Other’” (25). Within the canoe, Johnson can express the independence, exoticism, and sexuality inferred by the absent Native without having to explicitly delineate her own racial heritage.

The Independent Canoeing Woman

5 The cultural associations tied to canoeing that Johnson plays upon in her writing were not obscure. By the 1870s, recreational canoeing was booming, as mass production made all-wood and wood-canvas — as opposed to traditional birch bark — canoes widely available for the first time. Johnson’s own “Wild-Cat” was a board and batten, or “Peterboro’” canoe, made in the method perfected in Peterborough, Ontario. These all-wood canoes were produced by carefully shaping and tacking thin wood strips over a form (Neuzil and Sims 121-30).8 The wood-canvas models first produced along the Penobscot River in Maine used larger, less precisely fitted pieces of wood over a form to make the hull; it was made watertight with a covering of stretched and painted canvas (Neuzil and Sims 175-79).9 Whatever the mode of production, these canoes were cheaper to build and easier to maintain than birchbark models, and as such, canoes became popular wilderness recreation, a staple of camp life, and the centre of urban canoe clubs. Due to their widespread appeal, by the 1920s even people who never set foot in a canoe encountered its image in everything from magazine advertisements to tin-pan-alley songs.

6 Canoes became popular in the years leading up to the First World War in part because of the growing popularity of summer camps. While boys’ camps in both Canada and the United States tended toward militaristic activities and structure, and girls’ camps tended toward domestic, “Native”-woodcraft activities, in general camps were strange amalgamations of military order and bastardized Indigenous myth (Moss 124-25). Both girls and boys received training in two-person canoes and raced faux-Native “war canoes,” twenty-five and thirty-five-foot-long crafts paddled by seven to twelve people.10 These canoeing activities combined physical challenge with “Indian” fantasy, a phenomenon Philip J. Deloria describes in Playing Indian (1998). Deloria focuses his discussion of camps on the cultural debate between two founders of the Scouting movement in North America: American Dan Beard and Canadian Ernest Thompson Seton. Both believed in camping as an antidote to modernity for young boys, but each subscribed to opposing theories of that experience. Beard patterned his camp after an American frontier philosophy, stressing pioneering, marching, and khaki uniforms. Seton favoured quasi-Native activities such as plant identification, wood-craft, and canoeing. In 1903, Ladies Home Journal serialized Seton’s story of reforming a group of young vandals dubbed the “Sinaways” through a camp program he called the “Woodcraft Indians” (Deloria 95-98), later publishing the account as Two Little Savages (1903). Seton’s ideas influenced the development of women’s camp organizations such as the Camp Fire Girls. The militaristic “masculine” and Indigenous “feminine” coding of Beard’s and Seton’s respective philosophies is indicative of a larger debate within canoeing literature of the era.

7 Regardless of the author’s sex, canoeing narratives were rife with ambiguous gender codes. George Washington Sears, author of a series of articles in Forest and Stream under the fictitious “Indian” name “Nessmuk,” wrote masculine adventures including feats of wilderness endurance, but his manly escapades were coupled with moments of intimacy with nature and Indigenous domesticity. Woodcraft (1884), Sears’s popular guide to camping, is filled with directions for domestic chores and subsequent luxuries in camp — how to cook a good meal or make a comfortable camp bed. In other words, descriptions of domestic activities that could be coded as “feminine” always were central to his masculine narratives.

8 Indigenous domesticity was cultivated at women’s camps to reinforce conventional middle-class sexual roles: “Camp Fire Girls were to learn the true import of womanhood, defined as knowing the value of domestic work and appreciating art, beauty and healthy natural living” (Deloria 113). In “The Joys of Girls’ Camps” (Ladies Home Journal, 1915), Mary Northend and Una Nixson Hopkins relate that each girl “lays aside all conventionalities and adapts herself to the simple life of the woods, the mountainside or the lakeshore” (33). The article features photos of young women with braided tresses engaged in camping, swimming, horseback riding, and canoeing, but stresses that at the “close of the summer, the girl who was tired finds herself healthy and vigorous and eager to take up her duties at home” (33). Women’s camps were at cross purposes, encouraging independence while teaching commitment to the domestic sphere.

9 Evident in women’s canoeing journalism from the period is the conflict between canoeing’s healthful domesticity and the exotic independence it granted — an independence often tied to the canoe’s “Native” resonance. In “The Canoe and the Woman” (Outing,1901), Leslie Peabody describes an “Indian” possession upon seeing her first canoe: “All the Indian in me went out to meet it and the beguiling shape of the thing took complete possession of me. If you are to become a canoe enthusiast the subtle taking hold of you by the little savage princess of boats will be a thing beyond power of resistance” (533).11 Peabody goes on to say that while women are often described as “creatures to be stowed tenderly forward,” they should instead be “aft — where the paddle is plied,” meaning that women should steer (533). This control is both engendered and tempered by Indigenous “possession,” the “savage princess of boats” being a place to physically steer but emotionally lose control.

10 Isobel Knowles’s “Two Girls in a Canoe” (Cosmopolitan, 1905) also promotes this kind of abandon. Knowles describes paddling through the rapids in her “light bark canoe” as she and her companion “transmigrated into new bodies” after being “[b]ored mortals of the city, where we had turned the millstone of work and so-called pleasure” (649). Again, the canoe’s Indigenous resonance allows this so-called transmigration: “The canoe is the primal form of water craft. It goes back to the savage, and all the savage in me, all the instinct of revolt, bubbles forth as I paddle away from civilization” (650). Knowles identifies as “savage” the “instinct of revolt” and “wild abandon” the canoe grants her, and places this outdoor ardour in opposition to stifling domesticity.

Exotic Canoes and Canoedling

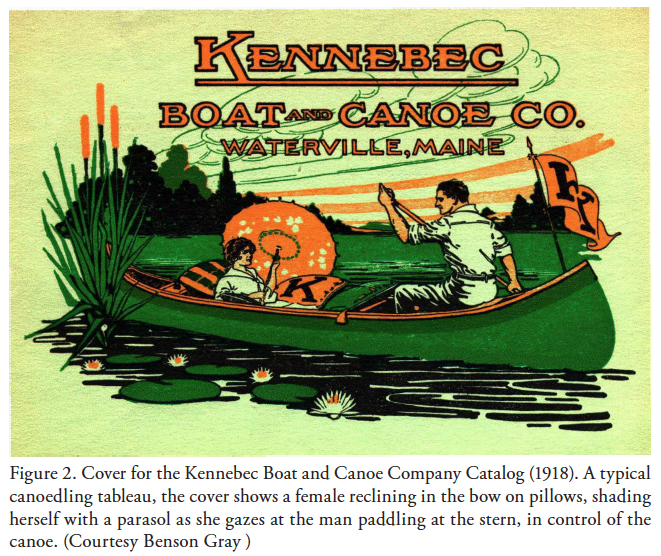

11 If canoeing excited “savage” independence and a woman’s control, it also evoked a kind of exotic allure that could lead to a loss of control. As women were learning to canoe at camp, canoeing was becoming popular as a remote — and sexually open — realm for courtship. As early as the 1880s, “canoedling” — the canoe-based variant of “canoodling” — was becoming a tableau in popular culture.12 The image of a man paddling at the stern as he woos a woman reclining on cushions in the bow recurred in magazines, calendars, advertisements, and postcards (see Fig. 2).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

12 Canoedling is central to Orestes Cleveland’s 1885 account of a carnival on the Charles River in Boston. From their bark canoe, Cleveland and his companion observe lamp-lit boats and picnickers on shore, but his description lingers on two couples canoedling:

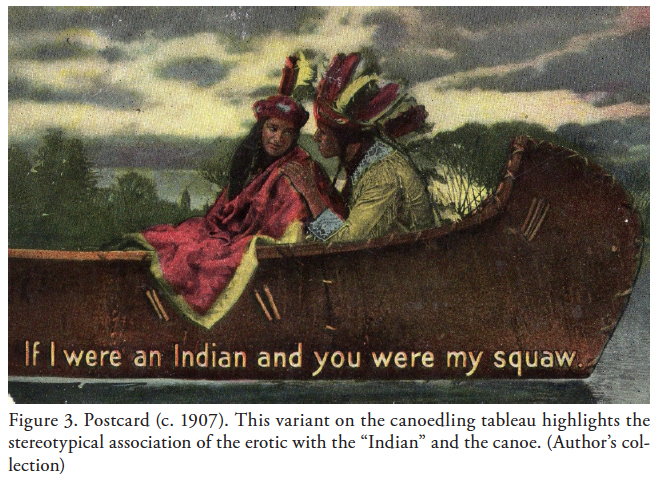

Cleveland’s description follows the canoedling tableau and suggests racial stereotypes. The “Viking” men and “pure Saxon” woman are figured as “graceful,” “beautiful,” and “fair,” but the “dark enchantress” excites Cleveland. Her “deep-brown lazy eyes” signify her position as an exotic Indigenous princess, and thus she is the “queen of the festival.” Her dark hair and eyes predispose her to be imbued with exotic and erotic possibility, one that gives permission to the stereotypically stoic “Saxon” figures in the canoe. Werner Sollors discusses how tragic “Indian” couples in nineteenth-century drama often provided space for Anglo couples to express forbidden romance.13 As the postcard above demonstrates, this sort of exotic fascination with erotic playacting as Aboriginal in the canoe continued into the early twentieth century (see Fig. 3).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

13 In Cleveland’s article and the “Indian” postcard, the allure of the Aboriginal “dark enchantress” emerges because canoeing — and its stereotypical Indigenous essence — brings forth “natural” tendencies of sexuality. Steven Marcus relates how Victorian pornography promoted the fantasy of awakening a woman’s “nature,” or her sexuality, often under the influence of an exotic culture. In The Lustful Turk (1828), English women are captured by pirates and sold into a harem where they discover their hidden sexual “nature” (Marcus 205). The canoedling tableau relied on a similar dynamic because the canoe holds an Aboriginal resonance that acts like the Turk’s exotic presence in awakening the sexual nature in his captives. The canoe presented a place where passengers could express primal desires. And as George Lyon notes, in the 1890s the canoe had not “yet been supplanted by the automobile as an erotic vehicle and portable bedroom. The erotic value of the canoe remained high . . . throughout the Twenties, and there were likely many more people than Johnson . . . who saw paddles as suggestive instruments” (153).

14 Victorian-era technologies of image reproduction gave the public greater access to images of private romance, so magazines, calendars, and prints often featured illustrations of couples courting in a natural setting — often in canoes (Anderson 74). Silver cigarette cases featured detailed engravings of elegantly-dressed ladies paddling canoes, and canoe manufacturers showcased women paddling together on their catalogue covers and magazine advertisements (Niemi and Weiser 175). Canoedling was also a regular theme in song, as Merilyn Simonds notes: “Water courtship became an institution, with the word ‘canoe’ serving as a staple rhyme for ‘you’ in the lexicon of ‘Tin Pan Alley’” (qtd. in Moores and Mohr 179). Popular songs of the era played upon the canoe’s Indigenous roots while cultivating the Victorian trope of courtship on water. In Harry Woods’s “Paddlin’ Madelin’ Home” (1925), for example, the singer relates how Madeline rides in his canoe, “ev’ry night” when “the moon is bright.” The singer and Madeline paddle at midnight, ignoring her father’s calls until the singer finds “a spot where we’re alone / Oh! She never says ‘No’ / So I kiss her.” The song’s title is ironic, of course, as the singer never paddles Madeline home. After the couple canoedles, he paddles “for one mile” just to “drift back for two,” hoping for the time when she will say, “Throw your paddles away.”

15 Johnson’s poetry demonstrates a keen understanding of canoedling tropes, though her poetry repositions women as in control of the encounter. Critics have long noted her use of suggestive language and her manipulation of gender dynamics in her canoeing poetry. “The Idlers” and “Re-Voyage,” for example, are canoedling poems with a strong sexual subtext, and each poem places its female speaker in control of both the canoe and the affair. In “The Idlers,” the speaker admires her male companion’s body, relating it to the curves of the canoe itself: “Your costume, loose and light, / Leaves unconcealed your might / . . . With easy unreserve, / Across the gunwale’s curve, / Your arm is lying, brown and bare” (25-26, 29-32). “Re-Voyage” features a female speaker who reflects on and revels in a past canoedling journey and sexual tryst. In language Gerson notes for being charged with “erotic power” (“Canadian” 101), Johnson connects nature and passion, the male form and the canoe:

Adrift in my canoe?

To watch my paddle blade all wet and gleaming

Cleaving the waters through?

To lie wind-blown and wave caressed, until

Your restless pulse grows still? (13-18)

The predominant metaphor within the poem is feminine control — of the canoe, of the man, and of the memory of the tryst. Johnson’s “Wave Won” and “Thistledown” broach similar themes, but all recognize canoedling tropes while asserting female control. Even “The Song My Paddle Sings,” Johnson’s most popular poem, presents a powerful speaker reveling in her control of the canoe in its intimacy with nature.

16 In a 1910 essay, Johnson reflected on her mother’s practical awareness of courtship in the canoe, claiming her mother “always conducted our conversations away from sentimentality as far as the opposite sex was concerned,” and that Johnson had “every liberty at home and no restrictions; we could go . . . canoeing alone with gentlemen” (“From” 60, 61). She suggests that her mother’s practicality regarding men allowed the Johnson sisters to navigate an acknowledged place for courtship. Charlotte Gray posits that it “was Pauline’s good fortune that her skill in the traditional Indian means of travel coincided with the canoeing craze” (106), but Johnson’s use of canoedling tropes shows that she found in the canoe a means to pursue her own course. In her essays, Johnson promotes herself as a capable New Woman, seizing control of her identity and negotiating the rapids of independence while steering between the rocks of male desire and Indigenous stereotype.

Johnson’s Club Pieces and Wilderness Journalism

17 Johnson wrote most of her canoeing articles during her traveling performance period between 1890 and 1897. She was a rare female author of canoeing pieces in venues such as the Canadian publications Saturday Night and The Brantford Expositor,as well as the American outdoor recreation magazines Outing and The Rudder. Johnson never attaches her performance name, Tekahionwake, to these articles, instead focusing on being a young, healthy woman both at the canoe club and in the wilderness: “In contrast to the decadent eroticism of the romantic canoeing poems, the dominant note in these pieces is the promotion of outdoor exercise in the interest of both personal and national health” (Strong-Boag and Gerson 157). These essays show Johnson altering her persona: titillating readers with the vision of a woman in control of her craft while courting rapids or flirting with men.

18 Johnson’s earliest canoeing journalism was published in Saturday Night, where she had been placing her poetry for several years. Primarily set on the Grand River or on the Muskoka Lakes, in these essays Johnson plays with themes she would later refine in longer essays. Published in the same June 1890 issue of Saturday Night as her canoedling poem “The Idlers,” “With Paddle and Peterboro’” follows a cruise on the Grand between Galt and Brantford. Johnson describes “handsome maidens and bright men” on a “bohemian afternoon,” and the trip alternates between scenes of idyllic nature and exciting whitewater. “Paddle” is one of the few pieces wherein Johnson doesn’t pilot the canoe, though she does end her story reflecting on a dream where “the winds splashing the waves across the gunwale, drenching my uncovered head and collarless throat with the coolest spray from the old Grand River” (“Paddle” 6). Johnson’s focus here is on abandon in nature, not control. In “Striking Camp” (1891), Johnson parsed the conflict between being seen as either a great paddler or an object of desire, in that women were faced with either asserting control or submitting to a man’s desires — or her own. When a woman paddles well, she notes, men want her for propulsion, not companionship: “[T]he girls who never paddle but loll gracefully with their backs to the bow, while they play the mandolin and look tender things across the center thwart, have much the best time of it, and somehow always have the best cushions” (“Striking” 7). Female canoeists must choose between being “revered” as a “good paddler” in control of the canoe or reclining in the bow as objects to be courted. Johnson also reveals, however, that knowing how to paddle allowed a woman to decide if she wanted to be pursued. As Jamie Benidickson has argued, Johnson was one of many women who savoured in canoeing the “satisfaction of doing something they were expected not to do,” even as they struggled with the ramifications of that unexpected behaviour (79-80). Johnson’s early essays brim with energy as she exults in acting outside the role of Victorian maiden or “Native” princess.

19 Johnson’s articles published in Outing have themes similar to those of her shorter Canadian pieces. Following treks in her custom-built Peterboro’ canoe, the Wild Cat, “Ripples and Paddle Splashes” (1891) and “A Week in the ‘Wild Cat’” (1893) establish Johnson as an independent woman and play with canoedling tropes. In both pieces, she mentions her First Nations heritage only in passing, while regularly representing herself as a strong, adventurous woman. The first paragraphs of “Ripples” depict Johnson and her “canoeing crony” Puck as exuberant young women while establishing the author’s canoeing authority. Johnson describes the Wild Cat as a kind of anti-canoedling craft: “Oh! But it was a beauty — not a court beauty, all varnished and polished and nickel plated, with brussels matting and velvet cushions, like some of those on the racks about us, but a sturdy little craft” (“Ripples” 48). And when Johnson talks of her canoe, she implicitly enforces her knowledge of canoecraft: “The decks were ash, slightly stained and varnished, and a brass keel ran the entire length. I had a great quarrel with the builder over that keel; he said it only increased the weight and was old fashioned, but I was obstinate, and many times afterward I had reason to be glad that I was so” (“Ripples” 48). The passage wavers between Johnson titillating the reader and asserting her control, as she evokes romance in club canoes filled with velvet cushions but follows this by establishing her canoeing knowledge.

20 Johnson’s plan for the maiden voyage of the Wild Cat is one “wherein we two girls were to ‘break the record’ and paddle eighty miles without the aid of masculine muscle” (“Ripples” 48). Her companion is Puck, a Shakespearean sylph and one inclined to stir passions in the wilderness, “a little English girl on her first visit to Canada, a girl with the grit and daring of a true Briton,” who — though inexperienced in the canoe just a month before — now “paddled like a native, steered like an arrow” (“Ripples” 48). The party consists of four couples in two canoes, two newlyweds as chaperone, the Wild Cat containing the author and Puck, and the other two canoes “manned at the stern and girled at the bow” (“Ripples” 48). Into the mix, Johnson scatters repeated canoedling references, including the black wine bottles in the party’s supplies. Once she establishes possible romance with the couples, however, Johnson focuses on her canoeing skill, especially compared to that of the men. When the party reaches the lake, Johnson describes paddling into the wind as “the hardest work I ever did in my life. . . . We had not yet got our muscles and joints ‘greased up’ for business, and it went very hard with us” (“Ripples” 49). Puck works “like a galley slave,” Johnson keeps “the bow into the wind,” and by “11 o’clock we had discarded our collars, caps and shoes and had got down to hard pan, for neither of us would give in” (“Ripples” 49). Their endurance and skill stands in contrast to the others: “Despite my efforts we drifted; but everyone else drifted also, and Norton touched shore oftener than we did” (“Ripples” 49). Johnson mentions earlier that she had taught Norton how to paddle, so in noting his tutelage and touching “oftener,” she emphasizes a paddling mastery not trumped by masculinity. Another male companion is neither skilled nor willing to recognize the skills of the women: “Every half hour the boy Johnnie suggested a lay off. ‘On account of the girls, you know,’ he said. ‘It’s too deuced hard on Puck and Paul.’ But we saw through him. Johnnie is the laziest drone about going up stream or against wind or portaging that I ever saw” (“Ripples” 49). Johnson reduces “the boy Johnnie,” exposing his gallantry as an attempt to mask his laziness.

21 In Johnson’s reflections on her canoeing prowess, she raises her First Nations heritage only when discussing camp sleeping arrangements. Admitting that on previous treks she slept on a camp cot in a tent, she has different plans: “My forefathers surely knew the secret of the happiest and healthiest way of tenting. You can’t take stretchers in a canoe, you know; so just roll yourself up in a blanket, tuck a cushion under your head and — snooze” (“Ripples” 49). The result is a night of suffering: “I pretended not to hear poor little Puck groan now and again through the night when she rolled against any particularly rugged point in the rock whereon we had pitched. I even pretended not to hear myself groan” (“Ripples” 49). While unashamed of her race, Johnson also undercuts her connection to the authentic, “wild” experience of sleeping on the ground, effectively distancing herself from that heritage. Even as she highlights her triumph of “eighty miles in a canoe — without a man — and nary a mishap,” Johnson subverts a connection between Indigenous heritage and an innate ability to camp or canoe (“Ripples” 51).

22 In “A Week in the ‘Wild Cat’,” the party consists of three couples in three canoes: a newlywed couple as chaperone in the Spider, Johnson and “Joe” in the Wild Cat, and Johnson’s cousin “Kate” and her “indispensable” companion “Rolph” in the Moccasin. “Week” focuses less on the feminine athleticism of “Ripples” than on intimate relations on the journey, both between paddlers and nature and between women and men. Early on, Johnson describes a moment when all the campers are mesmerized by the sunset:

Johnson’s description shifts from nature delicately and “imperceptibly” wrapping “her soft gray arms about the island” to the couple’s embrace. The single women sleep in their tent, the men in theirs, but the chaperones’ sanctioned tryst implies the possibility of illicit relations within the other couples.

23 In depicting her relationship with her canoeing partner Joe, Johnson inverts the canoedling tableau as she does in her canoeing poetry and takes the steering position of stern paddler. Joe can’t paddle or portage, but he does serve as an able canoedling passenger by waxing prosaic in the bow: “Joe is a very nice boy, and he recites prettily. He lies back in the canoe, and lets me manage the sail, paddle, steer, run rapids, and anything else, while he repeats, in a dreamy fashion, poems that breathe more poetry because of his saying them” (“Week” 47). Joe reclines, recites, and breathes poetry; Johnson maintains the titillation of the illicit romance while mastering the sail, steering a course, and conquering the rapids. Despite his wilderness inadequacies, Joe’s romantic skills hold value as Johnson rejects gender roles that would require him to take control of the canoe. As in “Ripples,” Johnson hints at sexuality without positioning herself as an object. She concludes the article by throwing the trek under a veil of mystery: “how are the rest of us going to stop Rolph telling yarns about his cruise? or, worse yet, how can we prevent him from telling some truths?” (“Week” 49). Johnson alludes to the possibility of romance and sex in the wilderness even as she pilots the journey.

24 Perhaps Johnson’s most complex essay published before the release of her poetry collection The White Wampum is “Forty-Five Miles on the Grand,” written for the Christmas 1892 issue of The Brantford Expositor. Strong-Boag and Gerson surmise that Johnson freely showcased her Mohawk heritage in this article because she thought local readers would be aware of her racial background (158). The essay includes scenes of canoedling and shooting rapids, but it also digresses into local history and an anecdote concerning Johnson’s father. “Grand” opens with a history of the Grand River in Ontario, including its importance to the Iroquois, its once-wild character in “olden days,” and its transformation into a “broad, semi-sluggish stretch of water” due to the mills and dams scattered along its course (“Grand” 184). Johnson then describes the thrill of running the “thick and fast” rapids on the thirty-five-mile stretch between the Galt and Brantford canoe clubs (“Grand” 185). Unlike most of her canoeing trips where she steers, here Johnson sits in the bow, and when she hits the rapids hears “the hurried plunge of the stern blade” rather than making it herself. As in her canoedling poetry, Johnson celebrates the “pliant wrist and mighty muscle” of her presumably male canoeing companion, calling him “master of rapid, paddle and Peterboro’” (“Grand” 185). Despite giving up control while running the rapids, Johnson still steers the narrative, positing the pilot as an object of desire and both pilot and passenger as “venturesome spirits” as they pass through the tumult (“Grand” 186). The paddlers then cruise into Brantford, where Johnson reflects on how its canoe club “invade[s] the river three times each summer, with flags waving, club colours flying, and each little craft laden down with fantastic devices in Chinese lanterns and torch effects” (“Grand” 186).

25 Rather than following this with an anecdote of a romantic cruise with her partner, Johnson again changes direction to ponder the scenic hills near Brantford where once “echoed the eerie death cry that told of up-stream murders and bloodshed; when the red man only lived and hunted and died” (“Grand” 187). She talks of a “now extinct Indian tribe,” its dying language, and the “one old woman, living on the Six Nations Reserve, . . . who speaks this forgotten tongue” (“Grand” 186). Against this backdrop of past or passing First Nations peoples, Johnson abruptly shifts to an anecdote about her father and a young Alexander Graham Bell. After Johnson’s father helped Bell run wires for his experimental telephone between his cottage in the hills and his house in Brantford, the inventor invites George Johnson to a group demonstration of the phone. During the exhibition, her father speaks Mohawk, befuddling the caller on the other end of the line to the amusement of Bell and the assembled party. Johnson evokes stereotypical visions of a passing Indigenous history even as she stresses her father’s lithe use of cutting-edge technology. Though “Grand” is in many ways disjointed, Johnson fits within it a heavy freight of cultural baggage, including the canoe’s Indigenous resonance, its wilderness thrills, and its significance as a social setting.

26 Essays such as “A Week in the ‘Wild Cat’” and “Grand” demonstrate Johnson’s ability to negotiate readerly desires and manage her identity in terms of ethnicity and gender roles; but this control became more difficult as her public identification with her First Nations heritage was solidified with the publication of The White Wampum in 1895. Strong-Boag and Gerson write that “[o]ver time, the role of stage Indian inflected her public identity, as evidenced by the increase in the Native content and Native commitment of her work” (113). Despite this fact, she still published only as “E. Pauline Johnson” in her canoeing journalism, including “Canoe and Canvas” (1895-96), a series of articles published in the American yachting magazine The Rudder. Along with her last set of canoeing articles, “With Barry in the Bow” (1896-97), these essays evince an even more strident independence in a traveling performer — not necessarily one of Aboriginal heritage — who paddles her own canoe.

27 The narrator of the “Canvas” series seems more mature than that of “Ripples” or “Week” because Johnson’s allusions to canoedling and sexual play are less veiled. “Canvas I” begins as a tour of a canoe club boathouse in February, when “We all begin to look for the spring thaws” (“Canvas I” 34). The essay moves from the inclusive “we” to a more intimate second-person “you” who dreams of summer at the club with “the splash of paddles, the pretty laughter of Tam-o’-Shantered girls, the genial whistle of all the boys” (“Canvas I” 34). Johnson then allows “you” to stroll through the “ghost house” of the canoe-club boathouse in winter, to “caress” a canoe and dream of the scrape “you gave her” last summer. That scrape came when “you” took a “Bohemian” boy out for a ride in the rapids and struck rocks when “you were watching a pair of saucy eyes that laughed out at you from the bow, and you forgot how near was . . . a million eddies” and “rapids beyond” (“Canvas I” 34). The allusions to sex are replete and layered — the canoe described as a “her,” the scrape a laceration on a “heart” — hinting at danger in dalliances beyond the thrills of shooting the rapids. Johnson fixes her bow passenger as an object, and the distraction of the narrator’s gaze causes danger in the rapids. The article concludes, “[B]efore another week closes, you and your favorite sport will be man and wife through all the glory of the summer days” (“Canvas I” 34). Johnson’s reference to marriage attaches serious consequences to the canoedling tryst. Similarly, in the second and fourth articles in the “Canvas” series, Johnson establishes a mature relationship with her canoeing partners, placing herself in the stern, steering position, but also admiring her partner’s physical attractiveness and paddling skills.

28 If Johnson is more direct with her independence and sexuality in these essays, she does struggle with the presence of First Nations men piloting her canoe. In “Canoe and Canvas III,” she and her traveling partner shoot the furious rapids of the Sault Saint Marie between Lake Superior and Lake Huron. Despite Johnson’s canoeing skill, she abdicates control when faced with these rapids and the Indigenous guides who regularly traverse them: “You don’t attempt to take the run by yourself (unless you have suicidal tendencies), for . . . you would rather enjoy lolling back in a canoe and having some sturdy Indians man the boat while you play prince amidships” (“Canvas III” 184). Her guides are “two splendid, giant Chippawas [sic], who owned a likely looking canoe, and in whose hands a paddle looked like a knife housed in its sheath. They inspired confidence at a glance” (“Canvas III” 184). This confidence rests upon the idea of an innate Indigenous ability to pilot the canoe. Though Johnson’s description of shooting the rapids exhibits the same vivid detail as her other essays, her depiction of the guides adds the exotic flavour of giving control to a racially over-embodied and “savage” Chippewa:

Johnson plays up the difference of her guides; their “Strange, eerie, uncanny” cries make the journey one to a past, savage world. She also portrays the Chippewa paddlers as timeless artifacts “invincible as fate” and “carved out of granite.” Even the canoe itself — a birch-bark model — gives the reader the thrill of riding in a prehistoric craft. If in her other “Canvas” passages Johnson titillates her readers by allowing them to ride with an independent, sexually confident woman, here she makes them dream of giving over control to a First Nations man.

29 The depiction of the Aboriginal guides in “Canoe and Canvas III” is a departure from most of Johnson’s canoeing essays, but it shows her difficulty in managing her multiple identities. In this case, Johnson may have been uncomfortable with how well the skills of her guides matched the stereotypes associated with Aboriginal men. These guides made their living shooting dangerous rapids, all the while selling themselves to white tourists who likely enjoyed their performed stoicism and “‘Hi! yi! Hi! yi!’” chants. Johnson’s representation of the guides is as much a caricature as it is a recognition of the painful nature of performing racial identity for an audience.

Stable Canoes, Unstable Identities

30 Johnson continued to publish canoeing articles through 1897, moving on to more domestic subjects or topics tied more to First Nations history thereafter. In the first installment of “With Barry in the Bow” (1896), her final series of canoeing articles, Johnson speaks of the unconstrained joy she feels every time she takes up the paddle:

This series in The Rudder shows Johnson at her most independent and confident, to the point of clarifying within the title that her performing partner “Barry” always sits in the bow, non-steering seat of the canoe. In this moment of joy in taking up the paddle — like many such moments in her canoeing journalism — Johnson revels in the control and the feeling of freedom she felt in the canoe.

31 This feeling of freedom stands in contrast to the demands placed on Johnson during her performing career and — after the publication of White Wampum — in her poetry and other writing. As Gerson and Strong-Boag have argued, Johnson “played the ‘trickster,’ carefully manipulating her audiences,” in order to claim “an inclusive nationality during an era characterized by racialized hierarchies and dichotomies” (“Championing” 50). This audience manipulation was neither easy nor without cost, for as Jones and Ferris note, if Johnson “has sometimes been derided as a sell-out to colonial commercial culture, it is perhaps more accurate to say that she used performance, both literally and figuratively, to make a living in her own time and place” (149). In contrast to the constant demands made on her identity while performing, Johnson clearly felt a sense of verve and freedom in her canoe. She reveled in writing about canoeing, about an environment where she controlled depictions of gender roles and racial identity with the slightest twist of her pen, much as her paddle controlled the path of her canoe. Inasmuch as these essays allowed her freedom, they didn’t solve the complex problems of representation and identity posed by an actual First Nations presence in the canoe, an Indigenous man who was also cognizant of his race as performance. The depiction of her Aboriginal guides shows that despite Johnson’s control over her identity in her essays, she too felt the influence of the expectations and cultural associations tied to the canoe.