Articles

Pacific Doors:

Earle Birney, Allen Curnow, and Pacific Modernisms

1 “It’s only by our lack of ghosts / we’re haunted”: few lines feel as familiar, and also as dissonant and as wrong, as Earle Birney’s often-quoted conclusion to “Can.Lit.” (One 58). What are Canadian literature and culture currently, after all, but a succession of hauntings? From stories of survival and resistance in residential schools to narratives of the internment of Japanese Canadians in war-time Vancouver through to ongoing journalistic narratives of the murder of Indigenous women and the neglect of them and their families by police investigators in recent times, Canada’s stories are full of ghosts, revenants, spectres, unsettled histories, and conflicts.1 Has Birney himself become a ghost figure, part of what David Damrosch calls the “shadow canon” (45), those writers caught between the “hyper canon” of often-cited authors dominating the literary ecosystem and the “counter canon” of resistant, Indigenous, and alternative voices supplementing and challenging the mainstream? The “shadow canon,” for Damrosch, exists in a strange kind of literary half-death, circulating in culture but not quite haunting it, acknowledged as having been a presence without ever registering in ongoing scholarly discussion, teaching, or debate. Birney’s (troubled) nationalism, his unreflective misogyny, his lack of interest in ongoing Indigenous experience in lands where, for his writing, the “Chehaylis are gone / & the salmon with them” (“What’s So Big About Green?” One 60): all of this pushes Birney’s books to the back of the cultural rummaging-drawer, unlikely tools to come to hand for our given moment. Scholarly trails take us away from these tracks through “the welling and wildness of Canada the fling of a nation” (“North Star West,” Selected 106) towards global and border-crossing themes and interests, from Jahan Ramazani’s arguments for a “transnational poetics” (23) to Susan Stanford Friedman’s recent proposal that we read “planetary modernisms” (1) in place of the old nation-bound canons Birney and his contemporaries did so much to construct and contest. In this kind of cultural context, what sorts of readings might make Birney speak to us again?

2 In this essay I read Birney’s work in dialogue with the works of New Zealand poet Allen Curnow (1911-2001) in order to argue for the relevance of returning to — if not always endorsing — critical nationalist perspectives in just such an era as our own, when renewed nationalisms in the wider political realm are overshadowing transnational and globalizing interests inside literary studies. Reading Birney’s poems in dialogue with the work of Curnow, his contemporary and New Zealand’s most celebrated modernist and critical nationalist poet, I want to explore some ways Birney’s particularly national obsessions and frames might be made to speak in our own transnational period. Reading two critical nationalists in this era — one where transnational and globalizing interests in literary studies are shadowed by renewed nationalisms and the return of the national question in the wider political realm — will, I propose, give us new ways of exploring these old questions of the relationships between nation, cultural nationalism, modernism, and history. Birney and Curnow haunt us, I suggest here, as our lacking ghosts, shadow companions to conversations ongoing but under-acknowledged.

3 Birney and Curnow shared internationalist, cosmopolitan sensibilities, and both read and wrote poetry, seeing themselves as part of a global English-language exchange of ideas and experiments. And yet both also contributed, in crucial ways, to the cultural nationalist projects of their respective countries. Birney, as a supervisor in the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, editor of Canadian Poetry Magazine (1946- 48), and later pioneer of creative writing education at the University of British Columbia, was enmeshed in institutions of culture (and culture-constructing) that were central to the nation-building ambitions of the Massey Report and cultural nationalism more generally: broadcasting, publishing, the universities. Curnow, like Birney a university teacher for much of his writing career, inspired the name of New Zealand’s first major literary quarterly, Landfall, with his poem “Landfall in Unknown Seas” (1942), and his landmark anthologies in 1951 and 1960 established the terrain on which New Zealand poetry is still explored in that country. Birney’s and Curnow’s poetry operates as part of a “shadow canon” in the history of cultural nationalism, however, as both, in important ways, opposed the affirmative, celebratory, official narrative of nationalism. Curnow insisted on the “stain of blood that writes an island story” (“Landfall in Unknown Seas” [1943], Collected 98) and Birney wrote of Canada as a place where “Depression triggers nightmares” (“Canada: Case History: 1945,” One 165). They were both thus in the cultural nationalist moment but not of it, critics of the national project at the very moment they serve in its formation. Too cosmopolitan in sensibility to fit comfortably in the narratives of cultural nationalism they helped, however unwittingly, to shape, both poets also proved too nationalist, however critically, to be re-positioned as forefathers by later generations of postcolonial writers and critics. This tense relationship between poetry, nation, and national imagination — a tension both writers kept productively unresolved in their work — offers one way to read these two figures together. Nationalism has been a crucial term for some decades in both Canadian and New Zealand literary studies, and yet debates about its significance are almost always also debates about the term’s very definition. Nationalism remains an essentially contested term, and reading Birney with Curnow offers opportunities to consider the shifting ways in which the idea of the nation is negotiated (and, at times, negated) in their work.

4 A comparison between these two writers can illuminate some of the ways in which Birney’s modernism responded to and imagined the problem of developing a critical nationalism. Birney and Curnow shared problems and contexts, in other words, rather than thematic commonality alone. Although the explicit connections between Canadian and New Zealand literatures have been relatively slight, as W.H. New’s (“Canada”) and Mark Williams’s survey pieces show, the two literatures share common problems. When Dennis Lee described Canada as, for the Canadian, “a place that is not home to you” (54), he could as easily have been describing New Zealand, that “land of settlers” Allen Curnow described, in a famous line, as having “never a soul at home” (“House and Land” [1941], Collected 67). I follow in this essay, then, a tradition of critics who have drawn the two literatures into critical conversation and comparison. New takes this approach to prose art in his Dreams of Speech and Violence, contrasting Canadian and New Zealand short fiction as a way of charting how the two cultures responded differently to shared settler-colonial dilemmas. New’s Reading Mansfield, pursuing a similar approach, opens with an unexpected, and Canadian, figure (Stephen Leacock) in order to think about a representative New Zealand colonial writer (Katherine Mansfield) positioning herself before the “Imperial Centre” (viii). My own essay follows this line in poetry, bringing texts together from Birney’s and Curnow’s 1940s works in order to find out what they might, in unexpected company, be made to say to each other and to us. Some of the techniques opened up through recent critical encounters with what Rebecca Walkowitz calls “comparison literature,” those novels “born translated” and already themselves participating in transnational market and reception contexts, can be read back into the literature of an earlier, nationalist moment of Canadian literary production as part of our search for different ways of sounding a poet like Birney. Comparison proceeds here in ways akin to soundings in music rather than the search for common terms in the way of thematic criticism.

5 Birney and Curnow share an aesthetic flexibility, producing both satirical and lyrical, deflating and rhapsodic poems. Both, for all this tonal restlessness, settled on remarkably consistent themes and concerns early in their careers. Land and settlement, ecology, colonial history (and violence), and travel, both imaginative and physical, feature across the decades in both poets’ oeuvres. Both moved from early adherence to tight rhetorical and lyrical patterning — rhyme and demanding formal constraints, the sonnet in particular, with Curnow; alliterative and other verbal patterns from Medieval poetry in Birney — to more colloquial, conversational later forms, although both adhered still to some syllabic and stress-based patterning across lines. Across long careers, publishing from the 1920s through to the 1990s, both had significant periods of re-invention and reformation in the 1940s. Curnow’s later works have a logic and trajectory of their own, and this essay focuses its comparisons primarily between the works of both writers from the 1940s, when both addressed most explicitly questions of critical nationalism and national history and audience.

6 Take this biographical précis as a starting point. A male writer born early in the last century makes his reputation through both an aggressive editorial and anthologizing campaign against what he perceives as the sentimentality, unreality, and placelessness of earlier and lingering “Edwardian” verses, while his own poetry combines modernist technique with a commitment to specificity; his youthful leftist commitments give way to mid- and late-career scepticism about political change and strong ecological poetic impulses; his best works, ones which, at the moment of their publication, were celebrated as nation-identifying, come by later critics during postcolonialism’s heyday to be seen as masculinist, Indigeneity-denying constructions of a narrowly nationalist experience and identity. This sketch, with all its distortions, could be applied as easily to Allen Curnow as to Earle Birney. What makes these two writers, in their two different traditions, so easily read in the same critical codes? Fiona Polack’s fascinating recent essay on Australian and Canadian fiction offers a model for comparison as a critical method:

Some of the best work in Canadian-Antipodean comparison has shown the difference of the Australian experience. “In order for modernist experimentation to become a viable mode of literary expression in Anglophone contexts beyond Britain and the United States,” Anouk Lang has argued, “it needed to find ways to articulate itself through the vocabulary and preoccupations of cultural nationalism. Correspondingly, cultural nationalists needed to find in modernist forms and styles appropriate vehicles for the expression of nationalism, if they were to make use of a mode whose complexities risked obscuring textual meaning and ideological messages” (48-49). There was in Australia, Lang suggests, no obvious connection between radical politics and radical aesthetics, and in fact cultural nationalism and “cosmopolitan” modernism emerged in opposition in the Australian context. Crucial to Canadian modernism, in contrast, were the ways in which it “was able to work in tandem with the range of agendas associated with cultural nationalism” (53), sustained as “a legitimate literary possibility through its process of contestation” (58). This was true also for Curnow in New Zealand. Australian cultural nationalism came early, with Henry Lawson’s bush ballads and tales and the Bulletin writers setting out a canon by the 1890s, and established itself sufficiently that, by the interwar years, it could stand in opposition to newly emergent modernisms. English Canada and New Zealand, in contrast, share the myth of national-cultural formation through the First World War, and have intertwined histories of belated, antagonistic, complexly nationalist modernisms. Curnow’s New Zealand work illuminates this combination of cultural, critical nationalism and literary, critical modernism in Birney’s Canadian oeuvre. Both writers were shaped by cultural contexts allowing them a space, unavailable in Australia, to make use of modernist modes for nationalist ends, and comparing the one writer with the other will, Polack’s method suggests, show up “textual and cultural phenomena” in each we might otherwise overlook, as well as providing useful reminders of shared histories and common critical dilemmas. John Newton, summarizing his account of New Zealand cultural nationalism, writes of “what may in fact be the most singular feature of (New Zealand) literary nationalism: namely that, unlike any other I can think of, it is formulated under the historical aegis, not of high or late Romanticism, but of modernist disenchantment. What does it mean to propose a discourse of settler nationalism downstream of modernism?” (15). But Newton’s question — and what he identifies as a “singular” New Zealand feature — applies, Birney teaches us, to Canadian literary studies, too. Birney and Curnow share modernist disenchantment as their poetic affective register: Curnow’s “At dead low water, smell of harbour bottom” (“At Dead Low Water” [1949], Collected 106) and Birney’s “the scum of tugs across her lakeblue eye” (“Transcontinental” [1945], One 48) are the dominant notes instead of any celebratory affirmation of maple leaves or kōwhai flowers. This poetry presents itself as cleareyed and unsentimental, insisting on what is and acting as a modernist diagnostic instrument — will Canada “learn how to grow up before it’s too late?” (“Canada: Case History: 1945,” One 52) — rather than a Romantic art of celebration. Disenchantment, critical national vision, connects both poets. How might that shared history — the internationalist in the nationalist — be read now?

7 Both Birney and Curnow pursued a critical nationalism, one concerned as much with contesting the nation-that-was as arguing for the nation-to-be. New Zealand in the 1930s and 1940s was, Allen Curnow recalled in 1972, a country that “did not know what to make of itself, colony or nation, privileged happy land or miserable banishment.” If “the polarization was nothing new,” Curnow claimed, “and it is still with us,” he and his contemporaries “were the first to find poetry in it” (Look Back Harder 244). The University of British Columbia, as Birney remembered it, was “a small and impoverished college in a society intent on primary accumulation on the edge of nowhere” (Spreading Time 21). It does us well to remember, in the face of the sometimes reductive frames that suit our teaching habits, that cultural nationalism was always cultural before it was nationalist, and there is little enough of the tourism advertising slogan in Birney’s Canada as “a highschool land / deadset in adolescence” (“Canada: Case History” [1945], Selected 95) or Curnow’s New Zealand as “a land of settlers / With never a soul at home” (“House and Land” [1941], Collected 67). Their work stressed the problem of the nation, a problem perhaps unsolvable but, for both writers, unavoidable. In the white settler colonies, the nation mattered as a project: the “stain of blood that writes an island story” (Curnow, “Landfall in Unknown Seas” [1943], Collected 98) and recognition that here “cool Cook traced in sudden blood his final bay” (Birney, “Pacific Door” [1947], Selected 142) are recurrent motifs in both poets’ works, reminders of the violence of colonial conquest, of the ongoing work of exploitation — of land, environment, aboriginal inhabitants — involved in nation-building. The political-colonial nationalist project of mapping, naming, and controlling is represented in critical nationalism through modernist disenchantment and discord. Curnow’s “Dialogue of Island and Time” has Island ask of Time:

Cities were planted, forests stripped;

Grandfather, father, and son

Have called me their own.

Surely there is something beyond

Plundering, possession of the land?

Show some landmark feature,

Not the past again, but the future. ([1941], Collected 82)

This, in another register, is what Jonathan Kertzer has called Birney’s “anti-romantic romanticism” (41), his emphasis on the land as unproductive of “positive” colonial meaning and prompting stories instead of conquest, violence, and an awkward, unsettling settlement:

“What happens to a national literature when the very idea of the nation has been set in doubt?” Kertzer asks. Reading Birney with Curnow highlights the doubt involved in cultural nationalism from the beginning, its emphasis on the bad faith and force in the narratives of “nation” it produced.2 This work of comparison helps reset our own critical questions. It is less a matter, now, of asking, “Is the nation still a relevant concept?” or “Have national literatures a future?” as much as it is an opportunity to ask, “How was ‘the nation’ made to work in cultural nationalism?” How did these two professed internationalists — Curnow always refusing the term nationalist with contempt and Birney insisting that he was an internationalist, preferring “the kind of citizenship which permits me to move freely in other countries” (qtd. in Cameron 482-83) — come to be associated with the literary project of critical nationalism and national literature formation?

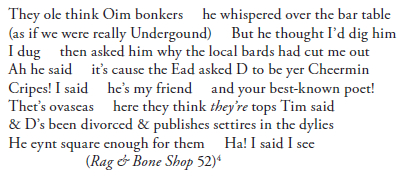

8 Biographical correspondences, although not central to my argument, shed some light on these questions and have been curiously neglected by scholarship on both writers. Birney and Curnow receive only passing mentions in each other’s biographies; Birney is missing from the index to Curnow’s life and Curnow’s name is misspelled in Elspeth Cameron’s monumental life of Birney. But the two men had a relationship lasting almost twenty years and were involved in intellectual exchange. Birney and Curnow both published in John Lehmann’s Penguin New Writing and the Chicago Poetry in the 1940s, and so may well have known each other’s work from early in their careers. Certainly Birney’s work was familiar in New Zealand poetry circles from the early 1950s, when Roy Daniells spent a term at the University of Otago and wrote on Canadian literature for Landfall, New Zealand’s major literary journal. Daniells’s “Letters from Canada” (42, 1957; 46, 1958; 50, 1959; 58, 1961) reported in Landfall on Canadian literary and cultural events for a New Zealand readership. Daniells lectured on Canadian literature to New Zealand audiences in 1954, and Charles Brasch, Landfall’s editor and thus one of Curnow’s publishers, made a note in his diaries (436) of Daniells’s connection to Birney. Curnow’s colleague at the University of Auckland and fellow poet Kendrick Smithyman spent time in Canada in the late 1960s, writing a (still unpublished) book on his experiences. Birney features as a character in one of Smithyman’s poems from this period, “How to get to Dollarton in 1969 and untie useful knots.” And of course Birney and Curnow were themselves personally acquainted, if not close friends. They lunched together when Curnow was in Vancouver in 1961. Curnow returned the favour when Birney visited New Zealand in 1968 and in the 1970s, so there was an ongoing personal connection.3 The two also socialized, Terry Sturm records in his biography of Curnow, at the Commonwealth Literature Conference in Brisbane, 1968, where they were both featured speakers. Curnow sent Birney what was most likely a draft of his “Introduction” to The Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse (1960), the originating document of New Zealand literary criticism; Birney found Curnow’s comments in this long critical document “provocative,” he wrote to Al Purdy, and hoped “to get around to quarrelling with them” (Bradley 106). I can find no print record of that quarrel being taken up, and Birney found New Zealand the place, if not the literary nationalist idea, uncongenial, writing to Purdy that he experienced it as “a cosy country, full of sheep and inappropriate place names . . . my writing just lies down and quivers” (Bradley 311). Birney published two poems about New Zealand, both stressing its conformity, lack of creativity, and isolation. “Christchurch, NZ” (1968) remembers the city as “a Victorian bedroom” peopled by irrelevant journalists and statues “freezing to death near the South Pole” (One 143). Curnow himself makes an appearance in a minor Birney poem, “kiwis” (1971), a recollection of the poet’s discomfort with what he experienced as New Zealand’s backwardness and puritanism:

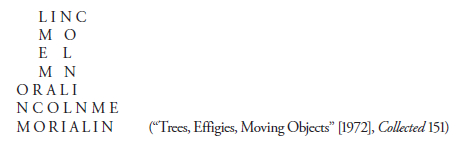

“Christchurch, NZ” and “kiwis” present New Zealand as a society saturated with a kind of horrifying conformity and boring dullness. This could have been Canada’s fate, Irving Layton once told Wystan Curnow, Allen’s son and also a poet and critic. Wystan Curnow’s polemical essay on “High Culture in a Small Province” opens with sentiments attributed to Layton that New Zealand is the nightmare alternative present contemporary Canada managed to avoid. But, for Birney, the experimental, divorced and “best-known” Allen Curnow stands as an isolated artist figure, fighting a critical nationalist battle against the mediocrity of his country. Moreover, both Birney and Curnow shared an interest in post-war trends in visual poetry: Curnow’s vision of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington —

— appeared just a year after Birney’s “Buildings” (Rag & Bone Shop 9):

Both developed sustained ecological visions and produced versions of what Kristina Getz calls “apocalyptic critique” (81) in their later poetry.5

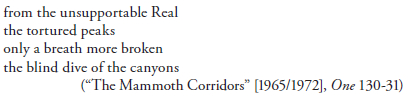

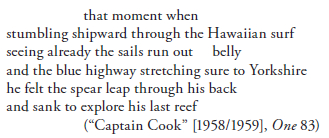

9 These biographical points of convergence are not so important for me here, however, as the two poets’ shared poetic strategies of disenchantment. Both work to imagine and give name and placing to the nation through exploration of it as, for settler-colonial society, a place of isolation, distance, emptiness, desolation. They write the nation as “a spark beleaguered / by darkness this twinkle we make in a corner of emptiness” (Birney, “Vancouver Lights” [1941], One 40). They figure distance as “they arctic we Antarctic; / Colder the southern cap, emptier the seas; / Horizon more emphatic / Stamps out one by one our flickering days” (Curnow, “Polar Outlook” [1941], Collected 65), and write of people as trapped, constrained, contained: “men are isled in ocean or in ice” (Birney, “Pacific Door” [1947], One 58). Those myths of conquest that might have sustained earlier national narratives are, in critical nationalism, exposed as comforting ideological fictions. “Land,” in Birney’s “Captain Cook,” “was a meaningless tramping of trees / a pikestaffed army pacing them all summer” as the colonizing explorer moved towards

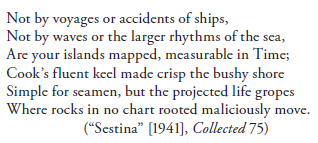

Curnow, too, refigured Cook’s explorations from the heroic register that had been common in the historical literature of his time into something more ironical, bathetic, and tragic:6

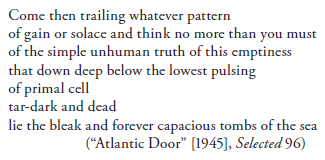

Cook, for Curnow, was a “Spider, clever and fragile” who showed “how / To spring a trap for islands, turning from planets / His measuring mission, showed what the musket could do,” his legacy a colony populated by politicians “howling empire from an empty coast” to a “vast ocean laughter” (“The Unhistoric Story” [1941], Collected 57). His packed sexual imagery of “the bushy shore” made “simple for seamen” by Cook’s “fluent keel” echoes in the ear Birney’s insistent sexualizing of the natural world, the “throbbing thighs of his mountain” in “Takkakaw Falls” (One 65). The insistent notes in both oeuvres, however, are distance and emptiness:

Critics have observed, justly, the erasure of Indigenous experience this nationalist emphasis on empty land produces; juxtaposing Curnow and Birney reminds us also, however, how unstable, self-critical, mind-altering visions of settlement are smuggled in by cultural nationalism’s use of modernist means. Birney’s “North of Superior” (1926/1946) seems, on a first reading, to be a lament for Canada’s emptiness and cultural desolation: “Not here the ballad or the human story / the Scylding boaster or the water-troll / not here the mind” (One 23). But, as the poem progresses, natural, inhuman forces are given culture and order. The “clangour of boulders” may be “barbaric,” yet trees have “rhythm,” and “stretching poplars” are “running arpeggios” (23). If “the breeze / today shakes blade of light without a meaning” (23), there is meaning imported, by the poem itself, and made rich and strange from the seachange it experiences in its translation from Scotland to Canada:

lopes the mute prospector through the dead

and leprous-fingered birch that never led

to witches by an Ayrshire kirk nor wist

of Wirral and Green Knight’s trysting (23)

Through a kind of apophasis Birney makes space for Robert Burns in Ontario: the witches of Burns’s “Tam o’ Shanter” are, through the imaginative force of the poem itself, now thinkable “north of Superior,” Scottish literary tradition translated into a new kind of “haunting” in the Canadian landscape. If the musical language for the “soundless fugues / of stone and leaf and lake” (23) might hold out the promise of some colonial “natural occupancy” (Linda Hardy’s term for white settler colonial fantasies of land possessed with the history of colonialism erased by utopian gestures), the Burnsian intertext forces Birney’s readers to see an active, shaping process at work in literature of settlement. The “skirl” of “vast inhuman pibroch / of green on swarthy bog of ochre rock” (24), with its Scottish words and musical terms, links these two movements together. Curnow, in a similar move, ventriloquizes his colonizer ancestor H.A.H. Munro as announcing that “Allen will get the Bible and the Poems” of Burns from the family inventory (“An Abominable Temper” [1973], Collected 192). The nationalist dream of settlement is always, in Birney and Curnow, a modernist narrative of myth and images broken and unsettled:

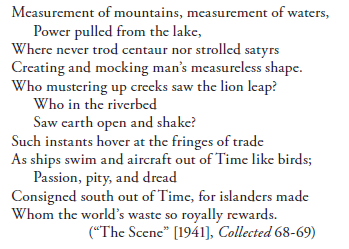

Curnow’s “The Scene,” like Birney’s “North of Superior,” highlights the ecologically destructive, shaping, controlling impulse of a settler-colonial modernity reshaping the land to its purpose. Hydroelectric power and the damming of rivers (“power pulled from the lake”) fit in Curnow’s vision where industrial forestry (“only silence where the banded logs lie down / to die” 24) and extractive industry (those “little wounds upon the rocks the miner / makes” 23) fit in Birney’s. Comparison helps us read these as suitably critical nationalists, staging in their “discords” (“North of Superior” 23) competing versions of colonial settlement, capitalist modernity contrasted with poetic exploration.

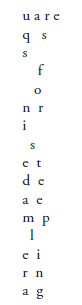

10 Birney is not, to be sure, unusual for finding emptiness and expressing what Northrop Frye identified as one of the two great topics of Canadian literature, the “primarily tragic theme of loneliness and terror” (258) out in the Canadian wilds. Comparing Birney with Curnow, however, makes visible the art and play at work in their imaginative negations, their modernist anti-world building. Their poems are neither simple lament nor mere celebration of ways of making the land new, and involve a constant oscillation between the two positions, a critical demand that writers follow the “cosmopolitan service” of making “a clear and memorable and passionate” interpretation of “Canadians themselves, in the language of Canada” (Spreading Time 76) followed all the while by poetry revealing this “language of Canada” as uncertain, dotted with intertexts, unsettling in its overlaying of North American land with European language. Reading Birney with Curnow shows us the ways Birney can be read as producing Canada as, in Phyllis Webb’s fine phrase, “unreal estate”: “in our search for a Canadian identity we fail to realise that we are not searching for definitions but for signs and omens” (109). We have become too accustomed, perhaps, to reading and teaching Canadian modernism as a variety of world-building. Curnow’s work, with its stress on how poetry functions to “introduce the landscape to the language,” prompts us to look for the artifice in Birney’s work, its willing collusion with readers seeing in its construction of Canadian “unreal estate” the process of landscape and language being made to fit together. “Sputter your pieces,” Curnow advises, “one

Birney’s Canada is best imagined, he wrote in 1946, “not simply as history or maple leaves or wheat, but as all these and also an enigma in human relations, a national illusion and a mysteriously frustrated promise” (Spreading Time 89). An earlier generation of revisionist literary historians in New Zealand criticism, excited by then new developments in postmodern poetry, criticized what they saw as the timid realism behind Curnow’s search for “that instinct for a reality prior to the poem” (LookBack Harder 172).7 The essay this line comes from, however, Curnow’s 1960 “Introduction” to The Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse, a work Birney’s letters to Purdy reveal had been shared with Birney in mimeographed form pre-publication, is one which begins with an image of the poet-anthologist finding himself “piecing together the record of an adventure, or series of adventures, in search of reality” (133). The adventure is in the search, in the activity of literature shaping that reality. The poems perform their own work of construction and undoing. Curnow’s poems revel in their own powers, in the processes by which “a word replaces a word. Discrepant / signs, absurd similitudes / touch one another, couple promiscuously” (“A Passion for Travel” [1982], Collected 249), just as Birney’s present their own workings for the reader to view:

between the unprinted river and the rubbed-out peaks

run the human typelines:

crops freshening to the water

farms split to sentences by editor death

fattening subtitles of rockfence

and roads the covered bridges have clamped

like caught snakes (“Page of Gaspé” [1943-50], Selected 102)

This Canada, contra “Can.Lit.,” is “haunted” by its ghost-writer, Birney himself. What would once, in Romantic hands, have been celebrated as a kind of poetic self-fashioning is rendered instead as modernist disenchantment, the “landscape introduced to the language” by way of metaphors of writing, composition, construction. This reality is a work of fantasy, “unprinted” rivers revising “rubbed-out peaks” from previous dreams of Canada. Business jargon (“Toronto Board of Trade Goes Abroad”), advertising signs (“Billboards Build Freedom of Choice”), the imagery of lettering and words themselves: all of this comes into Birney’s poetry as a way of carrying “the reader along with the poem” and with its “rapids and back currents” (One 187). Birney and Curnow offer ways of contesting the nation — thinking with and against the nation as imagined community — at the very moment they provide the vocabulary and imaginative resources for the reader to pursue this “mysteriously frustrated promise.”

11 I have avoided, to this point, introducing more recent critical tools from the developing fields of transnational modernist studies out of a desire to let the nation-disenchanting work of this critical nationalism get its proper attention. But what could be more appropriate for a transnational reading than the relationship of these two modernists, placed on opposite ends of the Pacific Ocean and sending back and forth world-building poetics and poetry to each other? Do Birney and Curnow not offer a case study in precisely the kind of global modernist relation recent criticism has urged us to pursue in place of tired national canons and questions? Perhaps. But the route feels too easy; turning to the “Pacific Door” of transnationalism too quickly may obscure the ways critical nationalism was always itself worrying at “the problem that is ours and yours.” “There is no clear Strait of Anian / to lead us easy back to Europe” (One 57-58): settlement needs to be recognized, imagined, cast in its own difficulties and historical “stain of blood.” What Curnow called “the trick of standing upright here” (99) is both a trick — an accomplishment, an art, a skill, and, perhaps, a bit of a con-job — and a way of thinking here — location, its historical and political specificities, the distance and connection between “Europe” and the “problem” of white settler colonialism and its ongoing reality elsewhere. These are current dilemmas, and juxtaposing Curnow with Birney shows some of the ways critical nationalism responds to, or even anticipates, through its nation-based poetics and projects some of the very questions transnational modernist studies tries to address. This may be, as Robert Zacharias has suggested in this journal, a case of the “transnational return,” “less a decisive move beyond the limits of the national frame than a complex extension of English-Canadian criticism’s habitual ‘worrying’ of the nation” (103). What Zacharias calls the “stubborn endurance of the nation as a focus of critical concern” (102-03) can be re-read in these foundational poets after, or as part of the transnational “return,” rather than as a separate, closed-off, and dated set of poetic concerns. As a product of Empire, Richard Cavell suggests of Canada, “we were international before we were national” (91); the complex intersections of international influence, national self-imagination, anti-nationalist critique, and critical nationalist modernism at work in Curnow and Birney show how much haunting energy will come from this dialectic of national and international, local and global, across Anglophone Pacific modernisms.

12 Larry McDonald, a generation ago now, identified a “suppressed tradition of affiliations, remarkable in both range and intensity, between Canadian writers and socialist ideology” (425), and subsequent decades have seen important work, by Bruce Nesbitt and others, documenting this “suppressed” tradition. What the process of comparison between Birney and Curnow reveals is that a similar “suppressed tradition of affiliations” can be found in the international sources of critical nationalism itself. Birney and Curnow’s modernist, critical nationalism carried a kind of internationalist charge inside itself, a “spectacular blossom” (Curnow, “Spectacular Blossom” [1957], Collected 130) of artifice and self-conscious interrogation contained in each piece of national discovery, travelling in the post from Vancouver to Auckland and back again.

13 The two poets’ fates have differed sharply in the decades since their deaths. Curnow’s Collected Poems were published last year alongside a full critical biography; he is at the centre of all anthologies, histories, and critical accounts of twentieth-century New Zealand literature. Birney, I suggested when introducing this essay, is a more uncertain figure, irregularly anthologized, adjacent to the contemporary concerns of the culture, in the “shadow canon” of mid-century modernism. I have made no case here for any dramatic revaluation of that reputation or this fate. What an exploration of these two modernists alongside each other opens up, however, through the “Pacific door” of critical nationalism, is a way of reading Birney for our own interests now, of locating in his modernist nationalism the tools for its own critique, for seeing how

Birney becomes legible, then, not as the seer who “foresees mankind’s career” in his own self-presentation, but as an explorer of what Zacharias calls the “foundational concern” of “Canadian literary criticism,” the nation, and its problems. Those problems continue in “the swiftly shifting set of spatial registers that make up our turbulent present” (120), and it is true to the spirit of a returning transnationalism in Canadian literary criticism that an encounter with a non-Canadian modernist might set this national question “in the world’s sphere” again.