Articles

Survival: Canadian Cultural Scholarship in a Digital Age

1 Globally, literary scholars are in the midst of a sea change in which culture, publishing, and scholarship are being reshaped in ways that will have massive impacts on how they do their work (McGann, “Culture”). Yet to date few Canadianist literary scholars have found their working methods substantially reshaped by this change, for reasons that this article will expound in thinking through the changing conditions of cultural scholarship in Canada. The essay begins by considering Margaret Atwood and her 1972 book Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature, which forty-five years ago brought nationalist urgency to a critique of Canada’s liminal position with respect to the forces of cultural production. The article then considers the future accessibility of primary texts for the study of Canadian and Québécois literatures as well as the need for scholarly engagement with the digitization and preservation of both the cultural and the scholarly record. I hope to elucidate the relevance of that elusive field of inquiry called the “digital humanities” 1 to the landscape of literary studies in Canada and in the process to cast both Survival and the current condition of Canadian culture and scholarship in a new light. Both Atwood’s engagement with the processes of cultural production and her engagement with new forms of textuality illuminate the need for proactive institutional and personal responses to the challenges of the digital turn for both culture and scholarship in Canada. I conclude the essay by outlining some key ways in which the challenges to CanLit might be addressed in part through shared digital research infrastructure, illustrated through the Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory.

2 Atwood’s responses to new technologies as both writer and critic are rooted, I argue, in an ongoing commitment to taking charge of modes of cultural production manifested in Survival. An early adopter — indeed a progenitor — of new technologies, Atwood is a cyborg insofar as she has extended the abilities of her physical body through technology. Her LongPen device for signing books over the ether has been taken up by the financial sector (Christensen; Melnitzer). A born-digital poetry prize was named in her honour (“Wattpad Poetry Awards”). She sanctions digital writing, and she does it, including collaboratively with game writer Naomi Alderman (Alderman and Atwood). Her novel MaddAddam inspired the video game Intestinal Parasites (Atwood, “Geek’s Guide”). As of March 2017, Atwood had more than 1.51 million followers on Twitter, outstripping one “@pmharper,” both now and when he was in office, if not “@JustinTrudeau.” She uses that far-reaching online public intellectual persona to promote literature, political and cultural views, and her own works. Atwood has contributed to the Future Library a book that no one can read until 2114 (Medley), and she has published on the free Wattpad platform and in new venues such as Byliner, a platform started in 2011 described by Adam Clark Estes as “Arts & Letters Daily meets Google News and has a beautifully designed baby.” In other words, as she explores potential futures, Atwood also indefatigably explores the future potential of writing and culture in the age of perpetually changing media and writing technologies. Hence, an announcement that she was releasing her own iPhone app was convincing enough for a Quill & Quire news item on April Fool’s Day (“Margaret Atwood Releases the Appwood for iPhone”).

3 As far as Survival itself is concerned, there is first of all its own liminal position, teetering on the edge that divides populist from academic study. This is reflected in Survival’s status, in Atwood’s own words, as an “easy-access book” that became “a runaway bestseller,” selling ten times its anticipated run of four thousand copies in the first year and saving Anansi Press from financial failure (Survival xvii, xv). The book has an uneasy relationship with the academy. It is widely credited with having established for the general public and the school system, at least, the very existence of Canadian literature. Serving as “a primer for teachers as well as students,” the book “had a profound influence on the way Canadians perceived their own literary tradition,” as Nathalie Cooke notes (25). Yet, according to David Staines, the book “incurred the wrath of many Canadian critics who failed to admit that she had done for her own literature what had not been done before” (18). Despite this accolade, it is one of just three passing references to Survival in the Cambridge Companion to Atwood. There is a sense that Survival belongs, as Faye Hammill says, to the “old-fashioned and — in some ways — misleading or reductive” school of thematic criticism “largely aligned with a White, anglophone perspective” (62). Notwithstanding periodic re-evaluations of Survival and its status as a kind of touchstone in histories of the field (Gadpai), CanLit has moved on from the critical methods and the cultural moment that spawned Atwood’s landmark intervention in the field. Can Survival give us any purchase, then, on current texts and technologies with respect to our literatures?

4 Cynthia Sugars, in her anthology Unhomely States: Theorizing English-Canadian Postcolonialism, groups Survival with George Grant and Northrop Frye in her first section on “Anti-Colonial Nationalism.” Atwood’s book was certainly driven by her fear of the country’s (re)colonization and cultural assimilation by the United States, bound up with the idea of the nation and the political agendas that get attached to that construction. We have come with Benedict Anderson to understand the nation as an “imagined community” caught up, according to Homi Bhabha, in the “performativity of language in the narratives of the nation” (3). Atwood clearly understood herself to be intervening in what Bhabha describes as “the field of meanings and symbols associated with national life” (3). The book was about cultural survival. It was, moreover, a deliberate strategy to use literary criticism to support domestic publishing and foster a nation-based literary culture. Atwood aimed to match the sales of a popular sexual disease manual that had bolstered Anansi’s finances by writing “a VD of Canadian literature” (Survival xviii). Appropriately, it went viral. The survival of Canadian and Quebec writers, of publishers, and of writing seems to be at least as pressing now, as publishing models are being radically disrupted by the advent of digital media, as it did in 1972 in the heyday of cultural nationalism.

5 Our current historical moment seems to be ill suited to a nationalist perspective, however. Nationalism is vexed and contested in a world in which capital leaps over national boundaries as easily as texts have always done. Not only is it, as Diana Brydon says, out of fashion for both critics and writers, but also the political climate has become more hostile to cultural nationalism since it is increasingly aligned with xenophobia and racism. Yet, in the past couple of decades, Canadian national identity has shifted discursively from an exclusively white, anglophone construction. Elke Winter argues that in the 1990s multiculturalism became “a social imaginary that is now widely endorsed by Canadians” (141). Although, as Winter notes, the Harper government did much to undermine the discourse of diversity in the early 2000s, since the election of Justin Trudeau there has been a renewed emphasis on pluralism and multiculturalism as inherent to Canadian national identity. The recommendations of a SSHRC-funded Knowledge Synthesis report (Bretz et al.) on sustaining culture and scholarship note that every major innovation in communications technology in Canada has prompted a national commission — until now, in the face of the largest shift in modes of communication since the invention of movable type. In this context and in homage to Survival, I contend that literary and cultural scholars can and should step up through activism, collaboration, and participation in the reshaping of our discipline and our culture by digital tools in the service of a nationalism committed to an inclusive Canadian cultural record. For Atwood, cultural nationalism had as much to do with how texts were produced, disseminated, and kept accessible as with their contents. Likewise, the challenges now facing Canadian literary culture and scholarship are intimately entwined with modes of digital production.

6 Texts have always been deeply imbricated with the technologies of writing, reproduction, circulation, and consumption. We see profound changes amplified regularly by purveyors of social panic and techno-panic (Breton; Carr; Keen) when new text technologies emerge. There is a particular version of this kind of panic within literary studies that generally circulates around a fear that working digitally means the death of books altogether (Birkerts; Brabazon). Few who work in the profession of literary studies are not deeply invested in the technology of the book, and most digital humanists would be the first to admit that current attempts at digital “books” are woefully inadequate compared with printed ones, in a range of ways. We are in the age of “digital incunabula” (Crane et al.; Guédon) with respect to both e-books and e-libraries, whereas we have had more than two millennia to work with inscription and more than five hundred years to refine print. As Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis point out, it took fifty years and the printing of eight million books before print had gained markers for “the information hierarchies of chapter headings, section breaks and subheadings” and navigational devices such as tables of contents, indexes, and page numbers (2). But there is no question that a radical change is taking place. Many of us now devour most of the texts in our lives by digital means, and they are almost all produced digitally. So it behooves scholars of texts to consider carefully the implications, the potential gains, the new possibilities, but also the evident risks and losses associated with digital texts. The latter, alas, are far too easy to see in the Canadian context right now.

7 Digital texts have proliferated in Canadian lives but sadly not enough in Canadian archives. As culture goes digital, researchers need robust archiving and preservation of both the printed output of the past and the cultural output of the future. Such archives are the fundamental condition of what we do, and we need to contemplate what stands to be lost. It is no secret that Canada lags behind most other comparable countries in digital cultural heritage initiatives (Beagrie; “Building”; Bülow and National Archives). The 2012 cuts to Library and Archives Canada and the National Archives Development Program were a clear sign, as the Canadian Historical Association put it, that Stephen Harper’s government had “gone to war against history, heritage, and ultimately Canada” (Lutz). The Harper government’s use of digitization as an alibi for cutting physical archiving was completely cynical given its cuts to the digitization budget as well. More recently, the Trudeau government has advanced digitizing Indigenous languages, cultural heritage, and oral testimony but has not committed to funding a national digitization strategy (Morneau).

8 While our archives are diminished and dismantled, as established by the expert panel of the Royal Society of Canada led by Patricia Demers (Demers et al.; RSC Expert Panel; “RSC-SRC Libraries and Archives Report”), the vast majority of Canada’s cultural heritage in print and other paper-based forms awaits transfer into current information formats, and an increasing quantity of born-digital culture and scholarship is slipping through the fingers of history. We are starting to lose the first generation of born-digital materials as the writers and scholars who created them move into retirement and lose institutional support, if they ever had it, or as media become obsolete. Thomas B. Vincent’s bibliography of about 140,000 bibliographical records from early Canadian cultural periodicals is one example of such a potential loss: published on a CD-ROM in 1993, it became inaccessible once digital reference works moved to online distribution. 2 Some types of text are particularly vulnerable when they exist in digital form alone. The cultural record on which we have relied for biography and literary history, for insights into the relationships between authors and publishers, increasingly takes evanescent forms as email exchanges, instant messages, and tweets replace paper-based communications. A European Union Comité des Sages report summed up the urgency of digitization programs driven by the public sector as follows: “Our goal is to ensure that Europe experiences a digital Renaissance instead of entering into a digital Dark Age” (7). Canada seems to be headed for the latter, in stark contrast to countries such as Sweden, whose vow to make itself one of the best IT countries in the world is backed by an aggressive national digitization program, or the Netherlands, in the midst of a program to digitize every out-of-copyright book or periodical in and about the Netherlands (“Koninklijke Bibliotheek”).

9 Quebec is doing better than the rest of Canada. The Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec (BANQ) and the Réseau québécois de numérisation patrimoniale have worked to coordinate digitization initiatives and raise funds for them. Concerted efforts since 2006 have included an inventory and survey of interested parties, which revealed that only six percent of the desired materials had been digitized; the next phase was the establishment of priorities and policies and a strategy for the harmonization of initiatives. The year 2010 saw the first call through the Réseau québécois de numérisation patrimoniale (RQNP) for digitization proposals funded by Quebec. Although the RQNP unfortunately seems to have foundered, the contrast between Quebec’s formulation of a digitization strategy and the federal government’s lack of one reflects more general policy differences with respect to the arts and recalls Atwood’s wry reflections on the position of the artist in Canada in 1999: “Have we survived? / Yes. But only in Quebec” (“Survival” 58). In English Canada, the Canadian Association of Research Libraries, the Canadian Research Knowledge Network, and the non-profit Canadiana alongside LAC/BAC struggle valiantly to coordinate something of a federal program without government support. Without vibrant and well-supported national archives, the record of both paper-based and digital Canadian culture will be spotty at best.

10 Even where national initiatives are in place, however, they are frequently not enough. A 2014 study by Loughborough University found that, after an estimated investment of £130 million over ten years, there were still significant gaps in digital preservation in the United Kingdom. Selectivity seems to be a given at present in most contexts; a study funded by the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) observed that “digital projects have tended to be driven by supply rather than demand, spurred by opportunity instead of actual need” (“Digitisation” 2, 4). Although they cannot address the need for large-scale digitization, then, scholars can contribute to prioritization, contextualization, and filling in gaps with focused collections or editions created to advance research, which is to say actual needs. We can also help with the specialized knowledge of our fields to work against the replication, in digital archives, of older knowledge structures and power relations. Digital cultural collections tend to replicate in both their inclusions and exclusions a traditional Western cultural record profoundly shaped by conservative forms of nationalism, by colonialism, and by social privilege. As literary scholars in a digital age, we are now in a position to help contest and remedy what Rodney Carter has characterized as “archival silences.”

11 There is an excellent fit between literary studies and the need to diversify the web. There are no CanCon regulations for the Internet, nor are there likely to be. There are ways in which literary scholars can partner with the archival community to counter the reassertion of outmoded canons in digital space, not just as advisers but also as partners in digitization. This does not mean usurping the role of professional archivists; rather, it means complementing it with different expertise and activities. One of the most significant aspects of the Web 2.0 environment is the shift in the balance of agency. “The digital mode of reproduction,” says Gary Hall in Digitize This Book! The Politics of New Media, or Why We Need Open Access Now, “raises fundamental questions for what scholarly publishing (and teaching) actually is; in doing so it not only poses a threat to the traditional academic hierarchies, but also tells us something about the practices of academic legitimation, authority, judgment, accreditation, and institution in general” (70). While the shift to digital publishing entails a major challenge to the structures of authority associated with academia, it also closes the gaps between research in progress and publication, opening the door to the wider accessibility of cultural heritage. Some researchers are already making this kind of contribution to the scholarly record and the public good part of their practices, making freely available digitized primary sources, bibliographic records, or other materials that advance knowledge but are not traditionally part of published results (e.g., Booth; Skinazi).

12 Those who undertake scholarly endeavours with a digital angle, even ones not primarily concerned with digitization, digitized content, and born-digital texts, can position their work to contribute to the survival of cultural heritage materials by ensuring that content created or collected in digital form will have the lasting value that comes from reusability, interoperability, and preservability. In this context, thinking beyond the interface is crucial. What a text looks like on a screen actually matters less in the long run than how it is structured, and the technologies for putting words on screens die much faster than some underlying formats. Although there are some beautiful websites out there, putting together a basic website that stores its content as separate pages in HTML or Hypertext Markup Language is the digital equivalent of using a mimeograph machine in the age of desktop publishing: such sites have significant disadvantages in terms of scholarly utility and longevity. Although there is no one-size-fits-all solution, meaning that careful reflection on digital methods is required before a particular strategy is adopted, standards and best practices have been established to ensure, as far as possible in a swiftly evolving environment still in its formative stages, that digital content can migrate easily to other contexts for reuse and preservation. Such standards take some learning, like any methodology, but most emerge from the library community or have been developed by humanities scholars and are eminently graspable. 3 As valuable as making texts accessible for human readers on the World Wide Web is, following best practices vastly expands their usefulness by making it possible for machines to help people find and reuse materials and above all to keep them available after a particular interface becomes obsolete. Digital tools are now ubiquitous, but the ones most used by literary scholars — online library catalogues or digital files in PDF formats are good examples — are surrogates of older technologies. There is a great deal to be gained from being critically aware of the possibilities and limitations of digital tools, of how digital resources work, and of how we use them, in order to see the possibilities beyond the frame naturalized by the different technology of the book. To think about the survival of literary culture in the digital age is to consider the qualities of digital text.

13 Text is social. It emerges from intellectually and materially situated practices, which mean that it is ineluctably related to context. It embeds différence in the social and deconstructive senses. Digital text begets text and not always legitimately: it changes, it travels, it becomes infected, it embraces new contexts, and it does so without regard for boundaries and authorities. It can be divorced from context in problematic ways; it is also amenable to being multiply and dynamically recontextualized. It is more copyable, more quickly and dramatically malleable and transformable, more pervasively distributable, more linkable and relatable, and more flexibly navigable than printed text. In other words, some of the affordances of digital media are well suited to certain propensities of textuality, including border crossing (Deegan). Brydon notes that “literature nowadays . . . is produced in a world of global connectivities in which there are no firewalls erected around the imagination.” Miran Hladnik, summarizing changes in Slovene literary study resulting from the digital turn, notes the exponential growth of data that invites reevaluation, the contextualizations that dispel the illusion of autonomous literature and literary study, and the relativization of authority. In other words, digital text has enhanced the conditions for the study of literature as Atwood, along with Franco Moretti and Electronic Literature Organization visionary Joseph Tabbi, advocated it — as comparative literature. As Atwood argued in 1972, “The study of Canadian literature ought to be comparative, as should the study of any literature; it is by contrast that distinctive patterns show up most strongly. To know ourselves, we must know our own literature; to know ourselves accurately, we need to know it as part of literature as a whole” (Survival 17).

14 New kinds of knowledge are enabled both by the quantity of text now available and by the kinds of access that we have to digital content through searches and database technologies. Media theorist Lev Manovich has argued that “database and narrative are natural enemies. Competing for the same territory of human culture, each claims an exclusive right to make meaning out of the world” (225). However, as Ed Folsom and Marlene Manoff observe, when a narrative sits on top of a database, as in the case of the Walt Whitman Archive (Folsom and Price), there is a symbiosis between them productive of new kinds of knowledge that neither would produce solo, offering new ways of linking argument and evidence. Far from taking us away from materiality, digital studies invite us to probe the relationships of media to context and content, precisely because in this form of textuality they are not a given. This is why the most exciting theorists of textuality of late have been those thinking about the digital, including Johanna Drucker, Katherine Hayles, Jerome McGann, and of course Marshall McLuhan, who influenced Atwood at a formative stage (Drucker; Hayles, Writing Machines; McGann, Radiant Textuality; McLuhan).

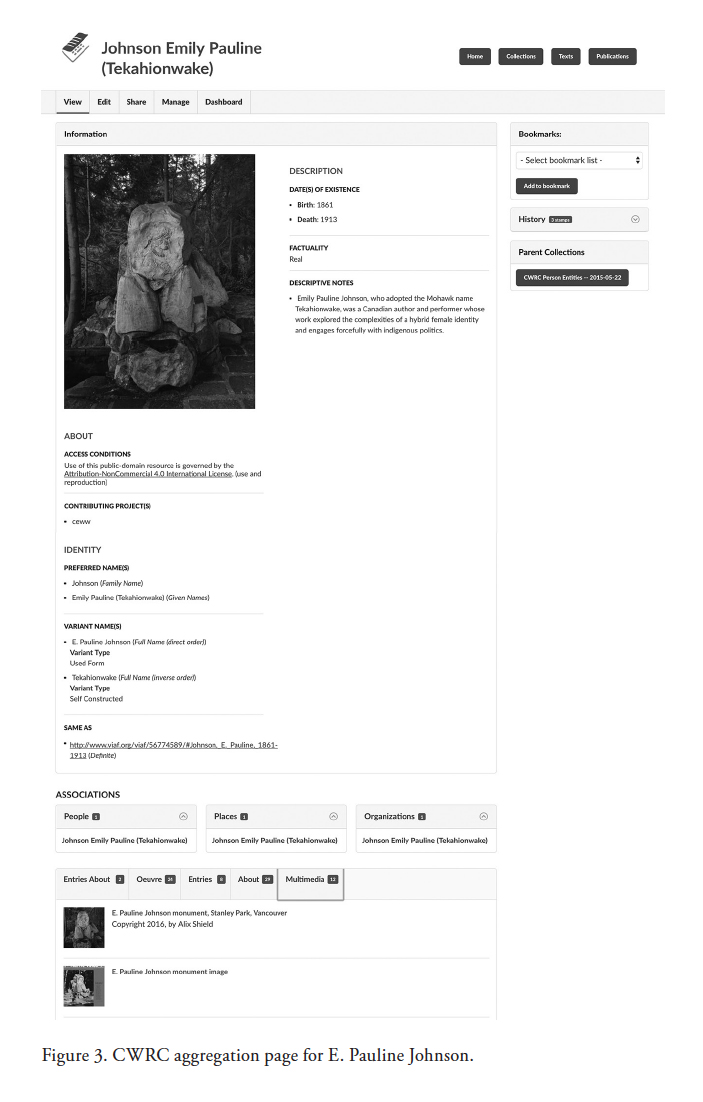

15 In many ways, digital textuality breaks the tyranny of close reading — illuminating and powerful a mode of engagement with textuality as it is — and pushes us to explore new methods of reading and interpretation, whether they fly under the flag of “distant reading” (as coined by Franco Moretti to denote engaging via computers with quantities of text too vast to be read conventionally), “algorithmic criticism” (as advocated by Stephen Ramsay for engaging hermeneutically using machines), or “surface reading” (advocated by Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus as an antidote to “symptomatic” reading, in which the critic presumes superior knowledge of the text). So it happens within this expanded context that a digital “book” might look like the original edition of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, as produced by a scanner (see Figure 1).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

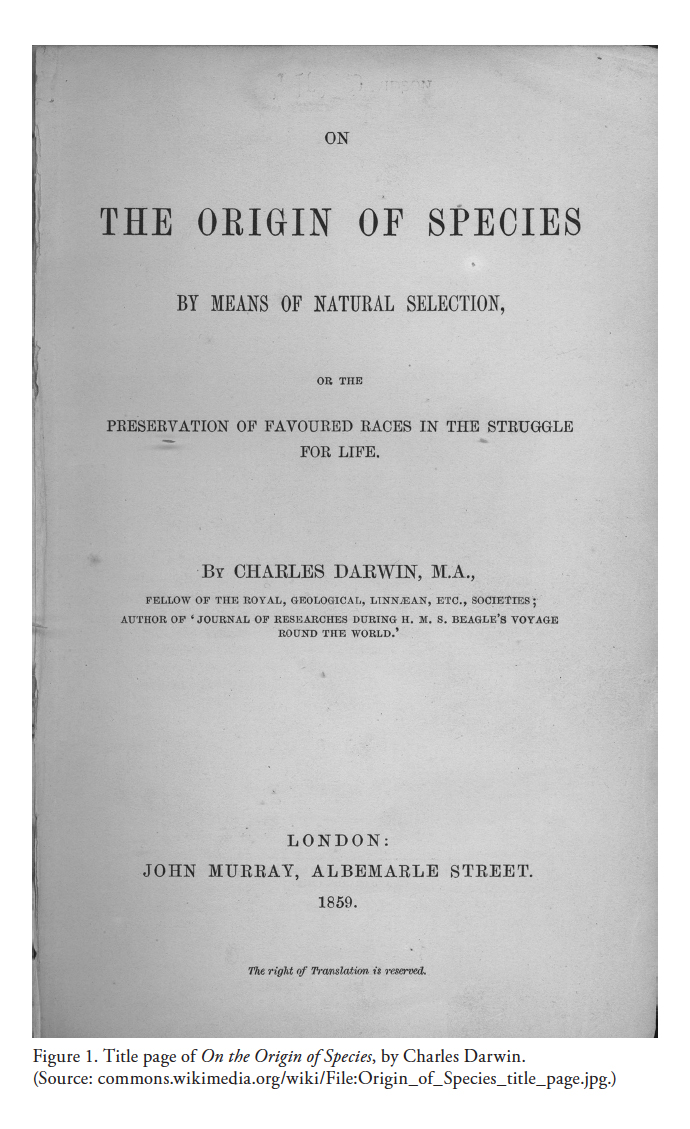

16 It might also look like Ben Fry’s “On the Origin of Species: The Preservation of Favoured Traces,” an animated and interactive visualization of the textual variants in the six editions of Darwin’s text (see Figure 2). Fry’s version of Darwin’s text is arguably fuller than any single print edition of the original(s) since it incorporates all six editions that appeared from 1859 to 1872 without privileging one over the other. Fry does not alter Darwin’s actual text(s) beyond adding a 272-word preface, but he creates an interface that provides unprecedented access to one aspect of that idealized but never instantiated text that we invoke when we refer to The Origin of Species without specifying the edition: its mutability, its instability, and its production over time through a series of material embodiments are all brought to the fore. To quote Fry, “The idea that we can actually see change over time in a person’s thinking is fascinating. Darwin scholars are of course familiar with this story, but here we can view it directly, both on a macro-level as it animates, or word-by-word as we examine pieces of the text more closely” (“Watching”). Margery Fee sees possibilities in such new forms of textuality, even if she is not quite ready to give up her paperbacks: “Not only are the media that transmit and produce text shifting, but so are what can be called reading technologies — or, if you like, literary-critical methodologies” (7). Indeed, Ramsay argues compellingly in Reading Machines: Toward an Algorithmic Criticism that the constraints of computation are compatible with older critical methods. Computers do not provide answers so much as new interpretive paths.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 217 Yet there has been relatively little uptake of new computational methods within Canadian studies. Canadianists seldom engage with digital methods despite the good support for such experimentation over the years from SSHRC generally as well as through the now defunct Image, Text, Sound Technologies, and Digital Economy initiatives. The reason is simple: copyright, copyright, copyright. Canada’s is such a young literature that little of it can be digitized without permission, though there are some sizable collections of earlier public domain materials in Canadiana’s Early Canadiana Online, Canadian Poetry Online (Kaszuba), and Library and Archives Canada’s online collections. There are of course contemporary e-lit practitioners such as the trailblazing Caitlin Fisher and more recently the innovative Sachiko Murakami with her interactive renovation poems (Fisher; Murakami), but a tiny proportion of Canadian print literature is accessible in a form amenable to digital scholarship because most of it remains under copyright, which creates barriers for certain kinds of work (at times more perceived than real) and makes it more challenging to amass and share good research corpora. Digital scholarship in CanLit therefore frequently tends toward a sociological, historical, biocritical, or bibliographical approach rather than working with the texts themselves, as in the exemplary work of Lucie Hotte, Julie Roy, Chantal Savoie, Carole Gerson, and Patricia Demers. There are some notable exceptions in primary text projects such as the recently revived Fred Wah Digital Archive and les Éditions virtuelles du Gabrielle Roy, but they are rare (Wah; Marcotte). This pattern holds outside Canada too: most digital humanities scholarship that involves working on texts themselves has focused on the nineteenth century and earlier. Only now is modernist literature starting to come out of copyright, and not coincidentally there is an upsurge in digital scholarship in this field, spurred domestically by the Editing Modernism in Canada research cluster that kicked off projects such as Canada and the Spanish Civil War: A Digital Research Environment (Sharpe and Vautour), producing both print editions and online resources (Garner; Harrison).

18 Given this state of affairs, it is urgent to affirm the scholarly right to use e-books and collections of digital texts for research purposes and to push for copyright law that allows freer circulation and use of Canada’s heritage in digital form. Most of us would agree, I think, with Mikhail Bakhtin that literature is always made up of the words of others — “I live in a world of others’ words” (143) — so why would we think that literary language can or should be locked down? Many publishers and writers fear for their survival given the increased reproducibility of digital texts, but draconian copyright laws affect the ability to circulate and analyze, write, and publish on other works. We need a generous interpretation of what constitutes fair quotation and reuse. Michael Geist has argued that Canada should be pushing the concept of fair dealing to its fullest extent. As far as the publication of scholarly work is concerned, for which many of us are remunerated by academic salaries, it is worth considering using a Creative Commons licence, particularly if the work is going to be digital. Cory Doctorow regularly invokes Tim O’Reilly’s assertion that, in our attention economy, “Obscurity is a far greater threat to authors and creative artists than piracy” (Doctorow 37; O’Reilly). Like Derek Beaulieu and other writers, Doctorow gives his writing away, whereas others are adamant about payment for their work. The disruption of the publishing sector by digital media is far from over (Alonso et al.), but in the meantime Canadian literature would be well served by improved access to digital texts for research purposes so that scholars can use them for text mining, visualization, and other new approaches to literary inquiry. Such use would not affect sales, could provide some texts with greater exposure than they would otherwise get, and would allow researchers to pursue questions that currently they cannot. The research, or “non-consumptive,” use of digital texts, including those in copyright or bundled in large collections and licensed to libraries, is slowly being established by organizations such as the Hathi Trust Research Centre (Butler; HTRC Task Force for Non-Consumptive Research Use Policy; Sag; Zeng et al.). What follows is the practical need for collections of content amenable to scholarly use. Libraries are increasingly taking the lead on ensuring that scholars can access for research purposes the data sets for large digital collections rather than having to use them only through the vendor interfaces. Using copyrighted texts for search, text analysis, visualization, topic modelling, or other forms of scholarly engagement should be considered perfectly legitimate research use, just like writing on the margins of a print book or examining it under a microscope. Establishing large collections for research use simultaneously addresses the need for the citability of data sets, the reproduceability of results, and long-term preservation.

19 As the challenges associated with copyright make clear, the potential of new text technologies to advance scholarly work exists in tension with the extent to which the environments — legal, ideological, and institutional — in which we work as students and professors of textuality are threatened.Mark Leggott, speaking with Trevor Owens, uses the term “ecosystem” to describe the open-source Islandora framework for digital repositories designed to promote reuse and preservation, and this kind of language is so ubiquitous that within technical discourse it is highly naturalized, not least in the rather disingenuous adoption of the metaphor of the “cloud” to describe distributed web-based computing (Bratton 116; Jaeger et al.; Owens, “Islandora’s Open Source Ecosystem”). The environmental metaphor should be invoked with care but can be helpful in thinking through the impact of change.The earth’s biophysical environment is composed of human-constructed and natural phenomena; indeed, the entire environmentalist movement ensues from the impacts of human activities on the natural world, so extending this language to talk about human products needs to take the parallel seriously (Brown and Simpson). In this consideration of new contexts for the survival of CanLit both as a body of material and as a scholarly field, however, the concept of an ecosystem proves to be an apt means of thinking through interrelationships, dependencies, and impacts.

20 One cannot talk about survival without invoking Darwin’s theory of evolution, which investigates how well organisms adapt to their environments and, over the long haul, how particular species adapt to changes in their environments. The survival of our cultural record is threatened along with our archives, and in large part as a consequence literary studies in Canada are not adapting as quickly as they might to the digital turn in the scholarly research environment (Brown). As Hayles has noted, there is increasing evidence from biology of epigenetic changes, changes initiated and transmitted through the environment rather than through genetic code; such biological changes can be accelerated by environmental changes that make organisms even more adaptive, which, as Hayles argues, means that “evolution can now happen much faster, especially in environments that are rapidly transforming with multiple factors pushing in similar directions” (How We Think 10-11). This suggests the advantages of mindful engagement with the human-formed environments in which scholars work and by which they themselves are being formed.

21 Adaptations to the new environment are seen everywhere, and some fly in the face of text-centred scholarship. Our students’ literacies are changing as print ceases to be the dominant cultural medium. Our own methodological literacies are also changing, as is our relation to non-textual media, which we employ increasingly in research and teaching. We are all digital scholars: we all work within “new knowledge environments.” 4 In this context, it is particularly important to be aware of infrastructure as a shaper of working environments. As Geoffrey Rockwell has observed, infrastructure, when it functions well, is transparent and naturalized. One very Canadian infrastructure is the silo, a necessary infrastructure that protects food from contamination, predation, and spoilage and provides the material conditions for best practices in resource management. In digital humanities contexts, however, silos have become a shorthand for the impediments to the interoperability and access that scholars most desire in electronic resources (Davis and Dombrowski). Silos are invoked negatively to describe how data often evade circulation in the public spaces where published information has traditionally been freely disseminated: that is, in public and university libraries. Canada doesn’t have legal deposit requirements for digital publications, so there is no space in which materials published in Canada must be made accessible to all. Digital publishers are not necessarily invested in the long-term preservation of what they publish, so their data are vulnerable to future loss. This amounts to a huge erosion of the public sphere that developed in tandem with print technologies, an erosion ironically resulting from the extension of copyright laws developed for print culture. Erosion of the information commons established in response to print-based copyright makes it harder, in a digital environment, to bring digital texts together for analysis. It is worth remembering, however, that a contrasting and exclusively Canadian version of the silo was developed in the 1920s in explicit opposition to commercial proprietary interests. Wheat pools were shared silos in which ownership of specific property gave way to a model of communal ownership for mutual advantage (Levine; MacPherson). Extrapolating this model to digital content, I hope to show that it offers the advantages of the silo while mitigating its disadvantages.

22 An infrastructure project that seeks to provide a kind of shared digital silo is the Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory (CWRC, pronounced “quirk”), which has arisen from the challenges outlined here. Its online environment is designed to be used by mainstream literary scholars, individually or in teams, working with a sustainable model for born-digital scholarship and the digitization of cultural heritage materials. I will discuss several features of CWRC that are particularly germane in this context. These affordances are not unique. Indeed, CWRC is literally built on top of and in partnership with other infrastructure initiatives emerging from museums, libraries, archives, and academia, 5 and similar features are available in various combinations in other online environments. This overview is thus meant to highlight how digital infrastructure can serve literary studies generally in the course of describing a platform produced to serve literary studies in Canada in particular. 6

23 “The Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory brings together researchers working with online technologies to investigate writing and related cultural practices relevant to Canada and to the digital turn” (Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory, http://cwrc.ca/about). This is the mandate of the CWRC project, designed to advance digital textual and cultural studies in Canada with a particular emphasis on Canadian cultural production. Its French name, le Collaboratoire scientifique des écrits du Canada, and its modest initial francophone content and start on a bilingual interface, indicate an aspiration to provide a bridge between the “two solitudes” of Canadian literary studies to bring together content, scholars, and communities. It is called a “collaboratory” in recognition that collaboration is a prominent component of much digital scholarship. CWRC aims to support a spectrum of collaborative activities, ranging from projects conducted by teams with multiple and distributed authorship to solo work undertaken by individual scholars. The latter might not seem to be collaborative, but when scholarship enables interlinking and interoperability it increases the resources available to scholars generally, reducing the amount of work required by others. A large component of CWRC’s infrastructure is therefore devoted to promoting standards ensuring that materials can be interconnected and shared.

24 CWRC seeks to enable scholars of writing in Canada and Quebec to produce work similar to the work of the Orlando Project, an early Canadian-based digital humanities project and experiment in literary history that has been seen as a game-changer in how we undertake literary scholarship (Ballaster et al.; Bowers; Reisz). The Orlando Project produced born-digital biocritical and contextual feminist recovery work that supports a wide range of inquiry through browsing, searching, slicing and dicing, and repurposing for various forms of reuse and visualization. CWRC also supports other research activities, including digitization, bibliography, multimedia collections, scholarly editions, and other forms of digital scholarship.

25 Due credit for digital scholarship remains a challenge in a number of institutional contexts, so the collaboratory is built upon the recognition that individual project identities are essential. A project’s set of home pages can thus have an individual logo and banner, and it can be customized significantly to highlight specific features, provide project-specific critical apparatus and documentation, and lead into a project’s collections. For projects with external funding, a unique website can be built on top of CWRC to provide an interface or functionality different from that of the main site, while the project materials remain accessible through CWRC and interoperable with the other materials that CWRC houses. Examples include the Canada and the Spanish Civil War project, with its emphasis on pedagogical materials, and The Digital Page project, with its custom reader for digital editions.

26 For projects involving multiple contributors, appropriate credit is crucial, so CWRC is incorporating ways to visualize contributions. CWRC allows not only for the management of editorial and other processes but also for the representation of an individual’s contributions to single texts and to projects or collections of texts in ways that make evident the extent and nature of the contributions. This kind of tracking and representation of contributions is particularly important to early career scholars, many of whom are currently pushed away from digital projects by hiring and tenure practices that favour more conventional forms of publication.

27 CWRC supports aggregation. Researchers can search across all CWRC projects simultaneously to find related materials, and future functionality will support also querying relevant external materials. In creating or editing content, scholars can create links to connect their materials with other projects while retaining their distinctiveness. An example is the group of projects that forms a broader set of resources on Canadian women’s writing. The profiles of Canada’s Early Women Writers led by Carole Gerson; the wealth of bibliographical and other materials in Women Writing and Reading in Canada from 1950 directed by Patricia Demers; the biographies of Canadian Women Playwrights Online led by Dorothy Hadfield and Ann Wilson; and more focused projects such as The Digital Page: The Collected Works of P.K. Page, edited by Zailig Pollock; Karen Skinazi’s project on Winnifred Eaton/Onoto Watanna — The Alberta Years; Cecily Devereux’s bibliography of early poetry monographs; and the Canadian content of the Orlando Project: they combine with other materials to provide a richer, more complete, and diverse digital representation of women’s writing in Canada than any single project could produce. Their differently inflected and sometimes contradictory treatment of their subjects provides a multifaceted perspective that other scholars can enhance and further nuance. As Linda Morra, Jessica Schagerl, and their collaborators have demonstrated, women’s archives are deeply mediated and political, whether stored on paper or in bits (see Morra and Schagerl). CWRC provides a foundation for a decentred and distributed approach to Canadian feminist literary history.

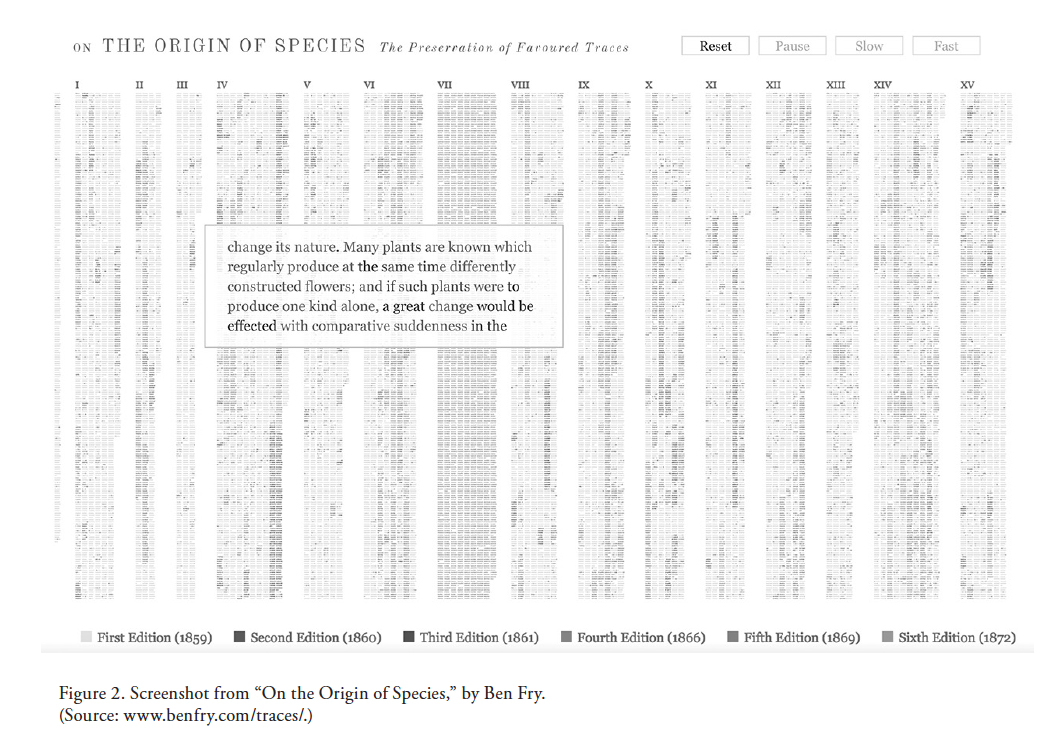

28 Aggregation involves not only being able to search across projects but also linking: CWRC connects entities — people, places, titles, organizations — across content. It will take time to arrive at a critical mass of material for many entities, but the potential of bringing together a wealth of materials from across projects is evident in the aggregation screen for E. Pauline Johnson (see Figure 3). This aggregated view combines basic information about her with organized links to associated materials within CWRC: entries about her and connected to her, works by her, secondary sources, and multimedia content.

29 To provide the basis for this kind of interoperability, the collabora-tory features a browser-based text editor called CWRC-Writer. This editor allows scholars to create or edit digital texts using standards that support textual preservation and interlinking right in their web brows-ers. A range of interfaces can be applied to content, including custom style sheets. In collaboration with Stan Ruecker and Stéfan Sinclair, CWRC also makes available the Dynamic Table of Contexts reading environment, which leverages the kind of sophisticated navigation that we get from print indexes within an online context, in contrast to most e-books, which typically exclude indexes altogether. This interface provides the basis for open-access scholarly editions, including hybrid essay collections emerging from CWRC conferences and published both in print form by the University of Alberta Press and in a free online edition (Carrière and Demers). The Dynamic Table of Contexts makes it easy to create online collections and can be used as the basis for teaching anthologies, student projects, or other editions.

30 Because reading is just one thing that you can do with a digital text, CWRC also enables different modes of engagement by enabling easier visualization of texts and collections through a bridge to the award-winning Voyant text analysis visualization suite developed by Stéfan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell. Beyond texts themselves, the collaboratory will soon make it possible to visualize relationships among the entities, the people, places, organizations, and texts found across CWRC materials: social networks, political networks, and literary networks that can help to elucidate both our past and our present. The open architecture of CWRC means that other reading and visualization interfaces can be plugged in or built to provide different ways of viewing its content.

31 Like the wheat pools that gave small farmers access to a common infrastructure, shared infrastructure for digital scholarship will be increasingly necessary given the modest funding that flows to humanities research. Moreover, given that common digital authoring platforms, such as those for blogging, are not conducive to long-term preservation, there will be pressure from funders to manage better the outputs of research. Shared infrastructure, of which CWRC is just one example of a number of initiatives worldwide, will make it easier and more financially feasible to produce digital scholarship in ways that gain from being put in conjunction and conversation with each other — in other words, from becoming interoperable within a dynamic environment. In a nutshell, CWRC is a bid to combine the ease of contribution of Wikipedia with a wider range of formats and scholarly quality control. It aims for long-term preservation or survival through collaboration rather than competition, along the lines of a wheat pool. This arguably Canadian strategy contrasts with the assumption that human nature is necessarily red in tooth and claw, in the words of Tennyson’s anticipation of Darwin, and indicates how we can modify our environments to our advantage and that of others.

32 Atwood’s Survival was an attempt to modify its environment too. Although it was criticized for arguing that the victim stance epitomized Canadian literature, it sought to critique and move beyond rather than reinforce that stance, not least in its attempt to intervene in the Canadian literary publishing environment. It can be understood as a rejection of the individualism and competition that characterized the standard view of Darwinian evolutionary processes and indeed of the dynamics of literary culture as conventionally understood. Rosemary Sullivan provides Graeme Gibson’s characterization of the historical moment and situation that produced Survival and Atwood’s public intellectual persona as one precisely of collectivity: “There was a kind of imaginative climate . . . that all of us . . . were a part of. One felt one was living in a kind of village, an imaginative village. . . . The group was better than the sum of the individuals. We discovered that that romantic nonsense that the individual artist has to be isolated was absolute crap” (Sullivan 266). That collectivity invoked by Gibson was not produced, however, around an unproblematized invocation of the nation. The same historical moment also produced Atwood’s Surfacing, a text in which the treatment of abortion, as Cinda Gault has argued, discloses a rift between the nation-state and the female subject position of the protagonist. The yoking of terms in the phrase “Canadian literature” was complex and fraught for Atwood.

33 Yet the book does promote them. Canadian. Literature. For all that has been written on its focus on the gloom and victimization of Canadian literature, it is actually a witty, indeed funny, and in many ways an uplifting book. It is a teleological book, embedding in its notion of “Basic Victim Positions” a narrative of progress from denial in position one through acknowledgement and anger to the “creative non-victim” stance of position four (36, 38). It is predicated, in other words, on an assertion of the possibility of change. Its articulation of the potential for cultural agency parallels slightly uncannily, but not surprisingly given Atwood’s feminism, the development of Wen Do Women’s Self Defence, a situated feminist approach to male violence that also launched in Toronto in 1972 in defiance of women’s positioning as victims (“Wen Do”). There is a ton of confidence and reassurance in Survival’s offerings of lists and lists of actually in-print texts and resources for those interested in Canadian writing and in its jaunty resistance to trends that Atwood reductively identifies and so drains of power. Thus, she reflects after her appendix on snow in the nature chapter that “Nature is a monster, perhaps, only if you come to it with unreal expectations or fight its conditions rather than accepting them and learning to live with them. Snow isn’t necessarily something you die in or hate. You can also make houses in it” (66). Survival reads much like Joanna Russ’s How to Suppress Women’s Writing from a decade later. Both authors straddle the writer/critic divide to create a feminized space for agency within literary and popular culture by means of strategic interventions in their environments.

34 This is a profoundly different historical moment in many respects than that forty-five years ago that begat the appearance of Survival, not least in our sense of the urgency of environmental thinking. Yet the nation, warts and all, remains the ineluctable context of strategies for the survival of CanLit and literary scholarship in this digital age. The nation-state is the operative unit for large-scale digitization initiatives, even within the European Union, though there are alternative models. One is the US-based Advanced Research Consortium (see ARC), a scholar-led initiative to provide peer review for digital scholarship outside normal publishing models and to aggregate digital resources in ways that defy both national and proprietary boundaries. However, all the major digitization initiatives break down nationally. One might argue that the mother ship of them all, Google Books, does not respect state boundaries, but it is being made to do so through lawsuits grounded in the intellectual property laws of nations.

35 So, in the spirit of Survival, this essay hopes to galvanize some energies toward change via a creative and constructive engagement with digital humanities. Adaptation is another word for learning. In 2010, Sidonie Smith, writing as president of the Modern Language Association, foresaw massive shifts in training as necessary to ensure the future of our disciplines and our graduates. Most formalized learning environments are ill equipped to facilitate this change, but organizations such as the Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory (HASTAC) are working to reimagine education in a digital world. And there are increasing opportunities for students and faculty to gain hands-on experience of innovative text technologies and to experience the lure of building texts and arguments, of engaging closely with cultural materials while advancing their preservation through digital methods.

36 Active and widespread engagement by a broad base of researchers with digital scholarship will modify our intellectual environments to support the effective adaptation of literary studies to digital tools and the adaptation of digital tools to serve literary studies better. There are claims that the digital humanities will transform the humanities and likewise pressures to #transformdh (Gold; Gold and Klein; Lothian and Phillips). Both will happen best with broader participation. More collaborative work and more social-facing work will mean that Canadian cultural scholarship circulates in new ways, contributing to the maintenance of a digital public sphere and increasing the pressure for a digitization strategy to ensure that Canadian literary culture is accessible and preserved in digital form. The symbiotic relationship between criticism and Canadian culture at the heart of CanLit will be revitalized, and what we can know about Canadian writing will expand. This is not to say that the terms of engagement are easy or obvious — far from it: a lot of experimentation, negotiation, failure, recursion, and iteration is needed. But the result might be new textual, intertextual, and institutional formations produced not by tech companies for which text is a resource to be mined and exploited but by those attuned to the complexities, power, and beauty of language as well as its ability to transform our selves and our worlds in continually mutating ways. If more of us push ourselves and our institutions in these directions, that will go a long way toward ensuring that, in this first digital age of the late anthropocene (Nowviskie), Canadian and Québécois literatures and literary studies not only survive but also thrive within a robust digital ecosystem.