Articles

Poetry beyond Illocution

Visual and conceptual poetry became significant practices in Canada in the late 1950s and 1960s as part of a dissatisfaction with what Antony Easthope in 1986 would call a moribund “bourgeois poetic discourse,” “the poetry of the ‘single voice.’” The latter, however, would continue to survive in school anthologies and arts council policies as a protected form, while the new non-discursive poetries found most of their audiences in art galleries, libraries, music clubs, on the internet, and as often through international presentation as Canadian. The result has been a rich accumulation of visual and conceptual poetry, with its own major figures, that is little understood or studied nationally and often better known and appreciated outside of Canada than within.

— Antony Easthope (Poetry as Discourse 161)

1 It is now not only forty years since the founding of Studies in Canadian Literature but also twenty-nine years since British literary theorist Antony Easthope pronounced lyric poetry, “the poetry of the ‘single voice,’” to be moribund and fifty-one years since bpNichol pronounced it and all “ordinary” or “regular” poetry to be already “dead.” “Dead but won’t lie down,” my late mother would have said, in a cliché nearly as old as the poetry in question. Easthope’s description of the condition of “bourgeois poetic discourse” in Britain in 1984 — its institutionally maintained audience, the popularity of other “poetic” forms — seems to be as accurate there now, as well as here in Nichol’s Canada, as it was when Easthope wrote it. The persistence of residual literary forms and the misrecognition of them as still dominant, of course, are not problems in themselves, unless they interfere both with the circulation of new work and with the recognition that culturally more relevant forms have already emerged, and thus harm the cultural standing of the genre itself.

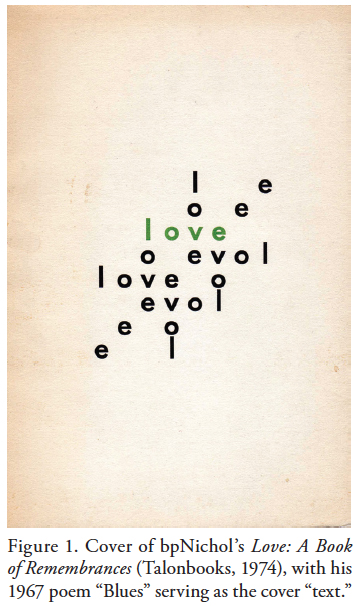

2 In my recent biography of Canadian poet and lay psychotherapist bpNichol, I spend some time on the arguments that the nineteen-year-old Nichol developed around 1964 for writing visual poems. Unaware of the international concrete poem movement then active mostly in Brazil, Britain, and Switzerland, he was calling his proposed new poems “ideopoems.” These visual poems, almost all constructed out of words, letters, or fragmentary sentences, would help him, he believed, to avoid didacticism and self-pitying emotional expression, which he saw as the main weaknesses of his attempts to write discursive poetry. He also believed that self-pity and narcissism were serious limits both to the Freudian psychotherapy that he was undergoing and to the success of any psychoanalysis (Davey 64-68). He would later call his early visual poetry a means of resisting writing poetry that was “didactic” and “arrogant” (“Interview” with Coupey et al. 154), poetry that was a “type of arrogance” (“Interview” with Norris 237) because it sought to “impos[e] some sort of preconceived notion of wisdom on the occasion of writing” (Bayard and David 19). In these arguments, one can perceive the shadow of earlier modernist arguments (also little appreciated in Canada in their time) against Victorian moralism and sentimentality and in favour of imagism, impersonality, and the collaging of images as in Eliot’s “Preludes” and The Waste Land, Pound’s “ideogrammic method” in The Cantos, and Woolf’s theory of the novel as a montage of still moments (see Banfield; and Goldman). But, more important for Nichol, one can also see the outlines of his later realization that a renewed, nonnarcissistic poetry was useful for general cultural health as well as personal sanity.

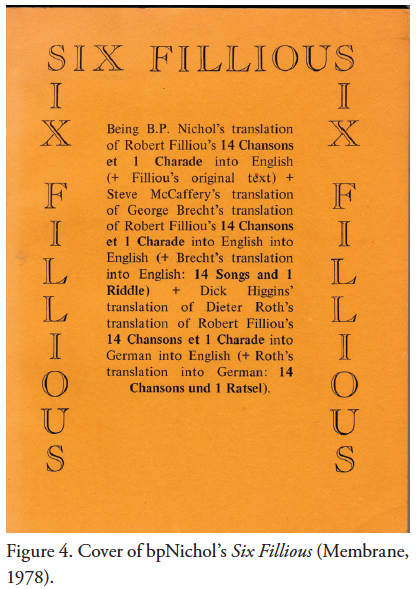

Display large image of Figure 1

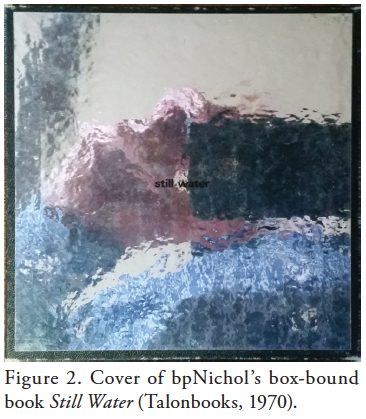

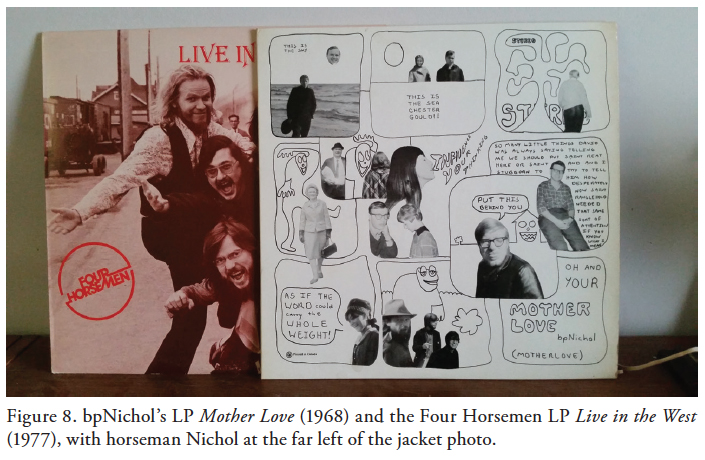

Display large image of Figure 13 Within months, Nichol became aware of international concrete poetry, including the work of other early practitioners in Canada such as Earle Birney, Lionel Kearns, bill bissett, and Judith Copithorne. He published his first book, all visual poems, with a British publisher, poet Bob Cobbings’s Writer’s Forum Press, in early 1967. With a micropress that he had founded himself, he published in 1969 a large envelope of mostly visual poetry by Birney, Pnomes, Jukollages, and Other Stunzas. This envelope contained, among other things, the first publication of Birney’s visual poem “Canada Council.” Among the three books for which Nichol co-won the 1971 Governor General’s Literary Award were two boxed, unbound collections of visual poetry, his own Still Water — its reflective silver “cover” itself a visual poem — and his anthology The Cosmic Chef. The third was the prose poem sequenceThe True Eventual Story of Billy the Kid, his first significant publication in Dadaist ’pataphysics — another mode that avoided explicit self-expression.

Display large image of Figure 2

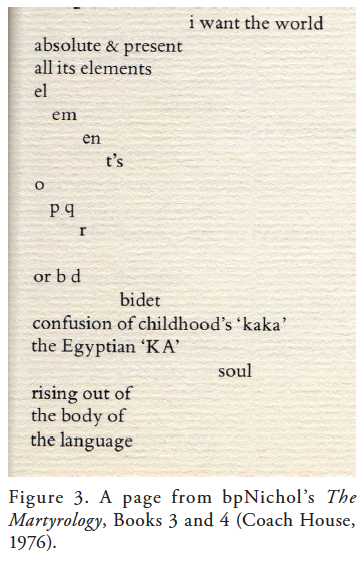

Display large image of Figure 24 Nichol continued writing discursive first-person poetry, though increasingly throughout the 1970s introducing ’pataphysical elements — science fiction histories, fictionalized saints’ lives — and elements from his visual poetry into it, the latter usually as a kind of visual poetry in process, in which the visual elements would develop as part of the syntactic argument of the poem (Figure 3). His 1971 view of lyric poetry was similar to Easthope’s later one: “[P]oetry being at a dead end” was “dead,” he would write in ABC: The Aleph Beth Book, a visual poetry suite with a repetitive manifesto running variously across, up, and down its margins; accepting that “fact” could leave us “free to live the poem” into new forms (passim).1 That the lyric’s unconsciously arrogant narcissism and individualism were part of a general cultural affliction, in which citizens and leaders alike made decisions and evaluations oblivious both to history and to the fate of humanity’s “we,” became the major implication of his continuing multivolume long poem The Martyrology. Why is a post-dead poetry necessary? For cultural sanity.2

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 35 But while nearly all of Nichol’s ostensibly first-person discursive poetry 3 was published and responded to critically only in Canada, notably The Martyrology, much of his visual and ’pataphysical poetry was published in Britain and the United States, where The Martyrology is still largely unknown. The reverse happened to his frequent collaborator, Steve McCaffery, with whom Nichol co-authored the Toronto Research Group (TRG) publications and the travel poems of In England Now that Spring.

6 McCaffery, who has created mostly visual and conceptual poems, is little known in Canada but widely praised in the United States.4 The split was especially unfortunate for Nichol, who had written all of his various kinds of poetry to be read as interlocking, a single work, and had struggled to find ways to reorganize it so that its interrelationships and cultural implications would be clearer to his readers (Davey 180-81, 205, 215-16). I suspect that he would have been appalled by the binary critical views of his writing— as dated lyricism versus avant-garde visual poetry and ’pataphysics — that have developed since his death in 1988 (see Bök; and Wershler) and possibly see them as similar to the sadly psychotic hallucinations of The Martyrology’s saints.

7 Regrettably, most contemporary readers seem to have interpreted his 1971 “poetry is dead” declarationas a mere literary figure; there is no evidence that any took it as a serious observation, one that the young poet had hoped would inspire action or response. His 1964-71 notebooks, however, show that the limited communication value that Nichol perceived in the conventions of established poetry was part of a personal crisis in which his self-disgust at often being willing to live superficially blended with his dismay that so much conventional poetry was being written to such little effect. When he wrote of the dominant discursive first-person poem as “ordinary,” he was calling it both banal and futile — much as he sometimes suicidally feared his own life might be becoming. The “poetry is dead” assertion of ABC therefore should also have been read as related to another 1971 poetics salvo: his satiric attack in The Captain Poetry Poems on Al Purdy, Milton Acorn, and “the courier de bois [sic] image of the [Canadian] poet: ‘you go into a bar, slam your poems on the table, and order a brew for all the guys’” (“Interview” with Norris 241). Macho self-display, Nichol believed, had become a Canadian sub-genre of the dominant lyric ordinary. His objections here were not a posture or an attempt at scandal; they were part of a serious attempt to liberate himself through alternative poetries from mere competence in an earlier period’s verse forms. He was not the only prominent Canadian poet to perceive the narrowly self-perpetuating field that “ordinary” poetry was at risk of becoming. The period 1964-71 was also when Leonard Cohen created and left behind a brilliant series of lyric poetry collections in favour of Easthope’s “popular song” and when George Bowering published Genève, the first of several major procedural poems.5 For Nichol, as for Cohen and Bowering, the problem of writing a new, and more relevant, kind of poetry was not a problem of content but a problem of form — a problem of genre, language, and medium. Nichol saw a “need to free up form — to unarmour the poem,” as “[s]yntax and the way you structure the sentence limits the content you can put out” (Bayard and David 28). As a collective problem, it was not going to be solved by enlarging the variety of ethnicities, races, or sexualities that wrote and published poetry, as desirably democratic a social goal as that was, because an interest in writing a poem does not necessarily imply an interest in freeing up the forms that limit what a poem can “say.” It was a problem that would be enacted vividly two decades later by Marlene NourbeSe Philip in her amazing “Discourse on the Logic of Language” (55-60) — a poem that, again, would unfortunately be read most often as a “mere” poem rather than a serious manifesto on poetics.

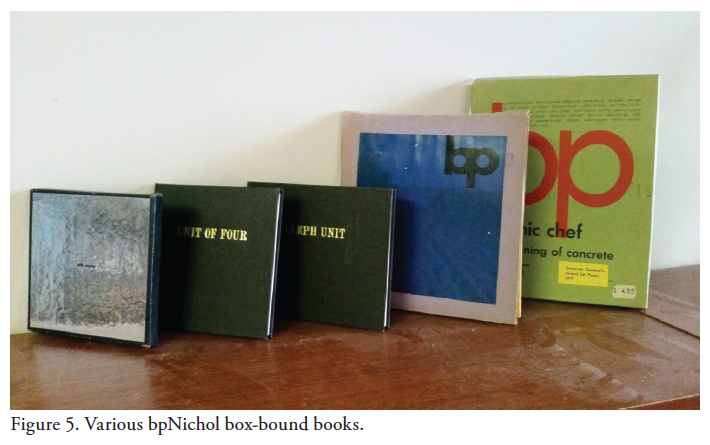

8 Nichol’s initial visual, sound, and conceptual work overlapped not only with the emergence in the early 1960s of international visual poetry but also with that of the multinational art group FLUXUS (initially called Neo-Dada by its organizer George Maciunas) in Wiesbaden and New York, though there is no evidence that Nichol was aware of the group or its members until 1966, when FLUXUS participant Emmett Williams invited him to contribute to the anthology of concrete poetry that he was editing for poet Dick Higgins’s Something Else Press. Nichol would eventually, in 1978, edit a book of Robert Filliou translations with contributions by Filliou’s fellow FLUXUS members Higgins and Dieter Roth and develop a friendship with FLUXUS sound poet Bernard Heidsieck. FLUXUS’ interest in boxed rather than bound collections of artwork (the “Fluxkit,” promoted by Maciunas from 1964 to 1973) was echoed in Nichol’s first Canadian book, the boxed bp from Coach House Press in 1967, in the award-winning The Cosmic Chef and Still Water of 1970, and in several later books produced by artist Barbara Caruso,6 but again there is no evidence that he knew of the Fluxkit7 — though he did likely know by then of Marcel Duchamp’s late-1930s Boîte en valise.

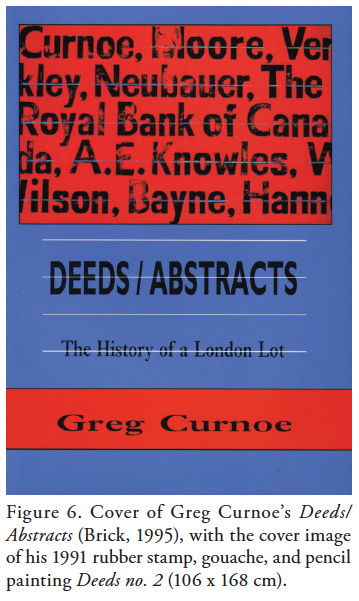

9 This somewhat indirect connection to Dada and “Neo-Dada” is similar to that of another major twentieth-century Canadian practitioner of alphabetic visual art, Greg Curnoe, who met and learned from Dada historian Michel Sanouillet in 1958 while Sanouillet was teaching at the University of Toronto (Elder 255). Curnoe’s interest in painting words and sentences might have come from Dada’s preference for non-artistic materials or developed from his creation of collages from ephemeral printed texts such as cigarette packages and bus transfers. Lettered text work made with stencils was among the first work that Curnoe created after abandoning art school in 1960. He would soon go on to produce rubber stamp and water-colour letterings of lists, words overheard, words encountered, or things he had seen or done.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 610 Both Nichol and Curnoe here were creating layers of non-lexical meaning by their acts of visually citing or reproducing the words and word clusters of these works. The words were displayed rather than said, avoiding the locutory act of the lyric poet — that is, avoiding any illusion of the artist having been the enunciator of the words written or cited.8 The enunciator of the text appears to be prior, elsewhere, other; in some of Nichol’s visual poems, enunciation, if understood as pronunciation, might seem difficult or unlikely. In the work of each artist, words have a scriptor or painter but not necessarily a speaker — as in Curnoe’s list of local workers (“Westing House Workers,” 1962), his list of comic strip characters (“Dessin Animé,” 1987), or his cryptic citation in a 1962 painting (O Let’s Twist Again) of the opening line of Chubby Checker’s 1961 hit song “Let’s Twist Again.”9 The materiality of imprinting words on paper, backgrounded or effaced in most poetry, is — especially in Curnoe — dramatically foregrounded. The possibility of a non-lettered painting or paintings or a discursive poem is evoked but left for the viewer to imagine. As US critic John Noel Chandler observed in 1973, Curnoe was “doing conceptual art and process art since before these terms were coined” (23). His replacing of realist painting with language was also in advance of US Language painters Lawrence Weiner, Edward Ruscha, and Joseph Kosuth and the British Art and Language group.10 Influenced by Curnoe rather than by Dada, Canadian poet-painter Dennis Tourbin created language work in the 1970s that similarly foregrounded materiality and obscured enunciation and, in a 1981 Art Gallery of Peterborough catalogue, referred to his paintings as “visual poetry.”11

11 The fact that Nichol, Curnoe, McCaffery, and Tourbin were displaying text rather than communicating linguistically/discursively through it expanded into visual and conceptual art that divide between “dead” poetry and poetry that could “live again,” and clarified it as a divide between artists who produce text to be viewed or, like Nichol in The Martyrology, to be viewed and experienced as a language event, and those who produce it mainly to be read as an encryption of a prior meaning. Displayed text links all of them to Vancouver visual and performance artist Michael Morris who in 1967-69 was creating single-copy concrete poems for gallery presentation as a form of visual art (Watson 78-79) and to contemporary conceptual poets such as Lisa Robertson, Peter Jaeger, and Christian Bök, who work with found or constrained text, and to the visual poetry of Derek Beaulieu.

12 In 2013, Toronto’s Power Plant Gallery presented the exhibition “Postscript: Writing after Conceptual Art,” which featured “paintings, sculpture, installation, video and works on paper from the 1960s to the present by over fifty artists and writers exploring the artistic possibilities of language,” curated by Nora Burnett Abrams and Andrea Andersson. Curiously, no work by Curnoe, Tourbin, Nichol, bissett, or McCaffery was included. The show’s title reflected the error often currently made that conceptual writing followed and was a response to conceptual art, when in fact it was part of the intermedia, visual poetry, sound poetry, Neo-Dada, FLUXUS, and performance milieu from which the concept of conceptual art emerged. The omission of 1960s Canadian visual artists appears to have contributed to the following observation by the curators:

Book binding did not restrain the work of Curnoe, though he was happy to produce between 1964 and 1972, in addition to his framed rubber stamp work, his “blue book” series of seven unique rubber-stamped book objects and an eighth published in bound facsimile by Toronto’s Art Metropole in 1989. Nor did it restrain Nichol, who distributed his visual text work as single-sheet pamphlets, quilted wall hangings, boxes of unnumbered, unbound pages, LP recordings, and in 1984 computer code on an Apple II floppy disk, as well as in the “increasingly obsolete bound structure” of the book. But however inaccurate the curators’ statement about the history of Canadian conceptual art and writing, it did point to how easily text distributed in non-bound or non-print media can be invisible to scholarly or curatorial scrutiny, whether in galleries, conference rooms, bound books, or bound scholarly journals. It also pointed to that current divide between the work of poets who continue older bound-book modes and those who work in intermedia or multimedia modes pioneered by artists such as Nichol, Curnoe, bissett, Birney, Morris, Tourbin, Copithorne, and Kearns.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 813 The Power Plant Gallery show with its strange implication that visual work created with language began in Canada in the 1990s with Darren Wershler, Christian Bök, and Michelle Gay, while beginning internationally in the 1970s with Marcel Broodthaers, Andy Warhol, and Sol Lewitt, also suggested how out of touch the Canadian visual art community might be not only with artwork such as Curnoe’s, or that of his contemporaries Morris, Tourbin and John Boyle, but also with the history of visual and conceptual poetry in the Canadian writing community. I do not believe that any major Canadian art gallery holds visual work by Nichol, McCaffery, Birney, or Copithorne except perhaps the University of British Columbia’s Belkin Art Gallery through its 1992 acquisition of the Image Bank archive of Michael Morris and Vincent Trasov. On the textual side, editor Gary Geddes famously removed concrete poetry from his 15 Canadian Poets anthology series in 1988 and from his 20th Century Poetry and Poetics anthology in 1985 (see Butling and Rudy 73-74).

14 Geddes’s slighting of visual and conceptual poetry in favour of perpetuating Nichol’s “ordinary” poetry was at least a somewhat informed gesture; in his recent memoir “Confessions of an Unrepentant Anthologist,” Geddes portrays himself as both conservative yet eclectic and knowledgeable enough to make token representations of Nichol, Lisa Robertson, and Erin Mouré in his latest anthology (70 Canadian Poets) to the extent that budget and conservatism permit. The Power Plant Gallery curators’ exclusion, even of mention, of Nichol, Curnoe, Morris, McCaffery, bissett, and Tourbin suggests only ignorance. Both exclusions, however, have serious consequences. Both obscure at least a fifty-five-year Canadian history of non-ordinary alternative poetries — a history of image-text, sound poetry, procedural poetry, mail art, collaborative art, and digital art at least as long as that of “conceptual art” in the United States and running parallel to the residual “ordinary” poetries that constitute the majority of the contents of Canadian secondary and postsecondary school anthologies. It is a history that has had its own multigenerational audiences in galleries, libraries, and music clubs rather than the largely captive undergraduate academic audiences that the anthologized “ordinary” poetries have enjoyed.

15 The Power Plant Gallery exclusions render both the included and the excluded Canadian artists as anomalies, concealing Bök’s and Wershler’s relationships, for example, with Nichol and McCaffery and instead presenting them as sidebars to the evolution of US conceptualism. The ultimate risk here is of portraying any innovative non-lyric Canadian poetics as an outgrowth of “Americanism” or “globalism” and depicting the authentic Canadian, as Geddes portrays himself, as marked by “the ingrained conservatism of the poor, or the poorly educated,” a “bias” that he hopes “has had the beneficial effect of making me concentrate on the poem itself rather than on theory or literary criticism” (211). The poem, Nichol would have argued, is never just “the poem itself,” existing outside time, but a text shaped by all those changing and “genuinely contemporary” cultural circumstances that Easthope (161) saw established poetic discourse straining to ignore. “Theory or literary criticism,” Nichol would have argued, is not antithetical to poetry but, as it has been to Philip, part of the field in which it is composed. It would be anti-intellectual to assert otherwise.

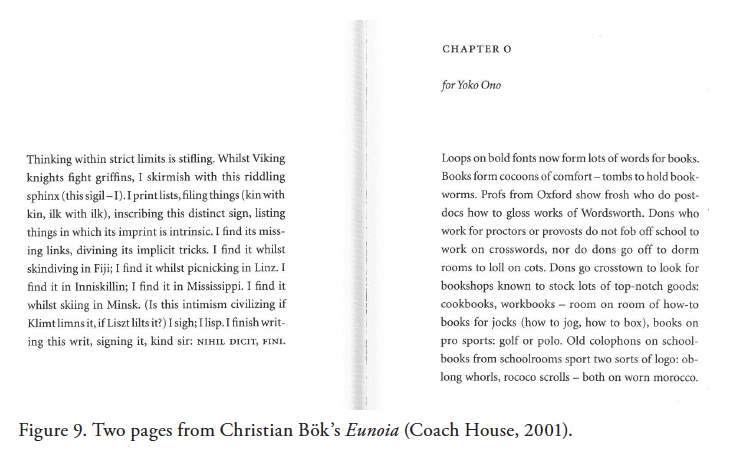

16 Poetry to be viewed more than to be read as discourse has appeared in divergent forms in Canada in recent decades. In 1996 Bök published Eunoia, a poem whose five sections are written within a principal constraint of each using only one of the five vowels and with “subsidiary” constraints such as each section being required “to describe a culinary banquet, a prurient debauch, a pastoral tableau and a nautical voyage” (103). The result is a performance text that can be witnessed, admired, but not “read” as representing something beyond its own linguistic procedures. In 2006, Bill Kennedy and Darren Wershler created Apostrophe by creating a search engine that culled statements beginning with “You are . . . ” from the Internet and editing them into a book-length poem refused entry by the Canada Council into the 2006 Governor General’s Literary Awards competition (see Bök, “Politics” 122-28). Search engine-based poetry became generally known as “flarf.” Also in 2006, Lisa Robertson surprised some readers when she told Chicago Review interviewer Kai Fierle-Hedrick that the lines of her highly praised 2001 poetry book The Weather were “all lifted” — but apparently not by computer-assisted lifting. Because of Canada Council confidentiality practices, whether any other books, such as Robertson’s or my 2011 flarf collection, the hard-to-mistake Bardy Google, have been withheld from Governor General’s Literary Awards jurors is difficult to know;12 certainly, the council’s initial intervention accorded with Easthope’s view of the state’s support of traditional understandings of what constitutes poetry. That intervention was also arguably anti-intellectual.

Display large image of Figure 9

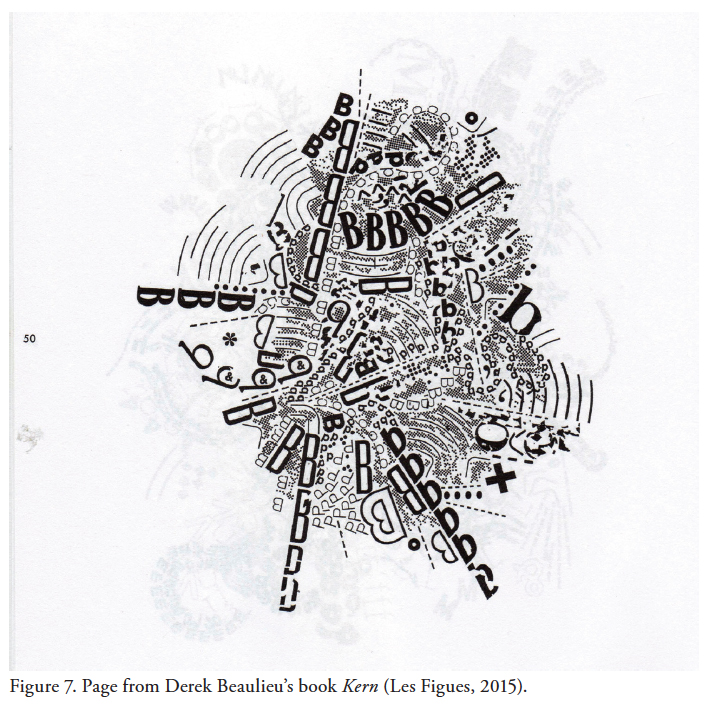

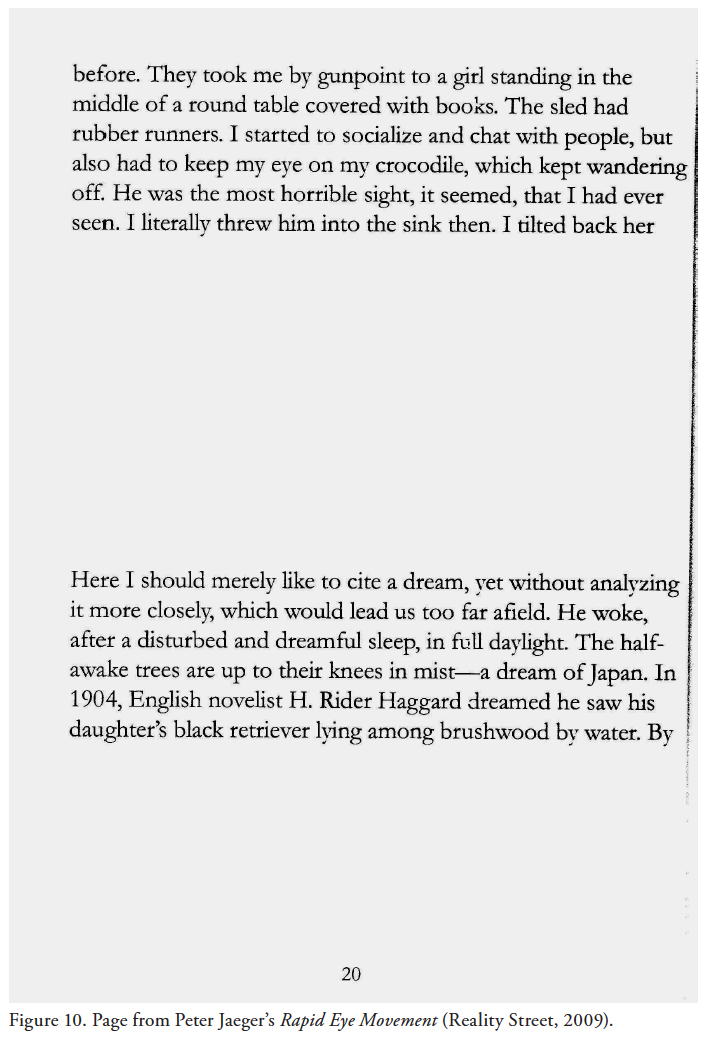

Display large image of Figure 917 Meanwhile, Peter Jaeger published Rapid Eye Movement (2009), a one-hundred-page collage of found sentences half of which are from dream accounts and half which contain the word dream, and The Persons (2011), a fifty-page exercise in life writing in which the “persons” are each given no more than two found sentences, no two sentences consecutively. Each sentence begins with a name followed immediately by a verb and is appropriated from an existing source, whether emails, lyric poetry, travel literature, newspapers, psychoanalytical literature, diaries, religious literature, and so on, and arranged in an apparently random order. The book was published by the British visual art press Information as Material. Jaeger has commented that he feels particularly drawn to the visual arts: “It never ceases to surprise me how far the ‘high-street’ poetries lag behind visual art discourses in their conceptual development,” he told interviewer rob mclennan. “As [US poet] Ron Silliman said, ‘they write like the 20th century never happened.’” Jaeger is one of a handful of contemporary British residents included in Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith’s 2011 Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual Writing but in the company of eight other Canadians: McCaffery, Beaulieu, Bök, Kennedy, Wershler, Donato Mancini, Philip, and Dan Farrell. Bök himself published last year (2015) book one of a new poetry project, The Xenotext, designed to encrypt in the DNA of a nearly indestructible bacterium a short poem that will preserve our humanity long after mammalian extinction. Many of its pages present scientific formulas to be viewed and — once again — textual performances to be admired. The bacterium-encrypted poem is unlikely ever to be anthologized by Geddes, but it has been designed to blithely survive all those poems that have been. Bök, not surprisingly, is a notable absentee from Geddes’s 70 Canadian Poets.

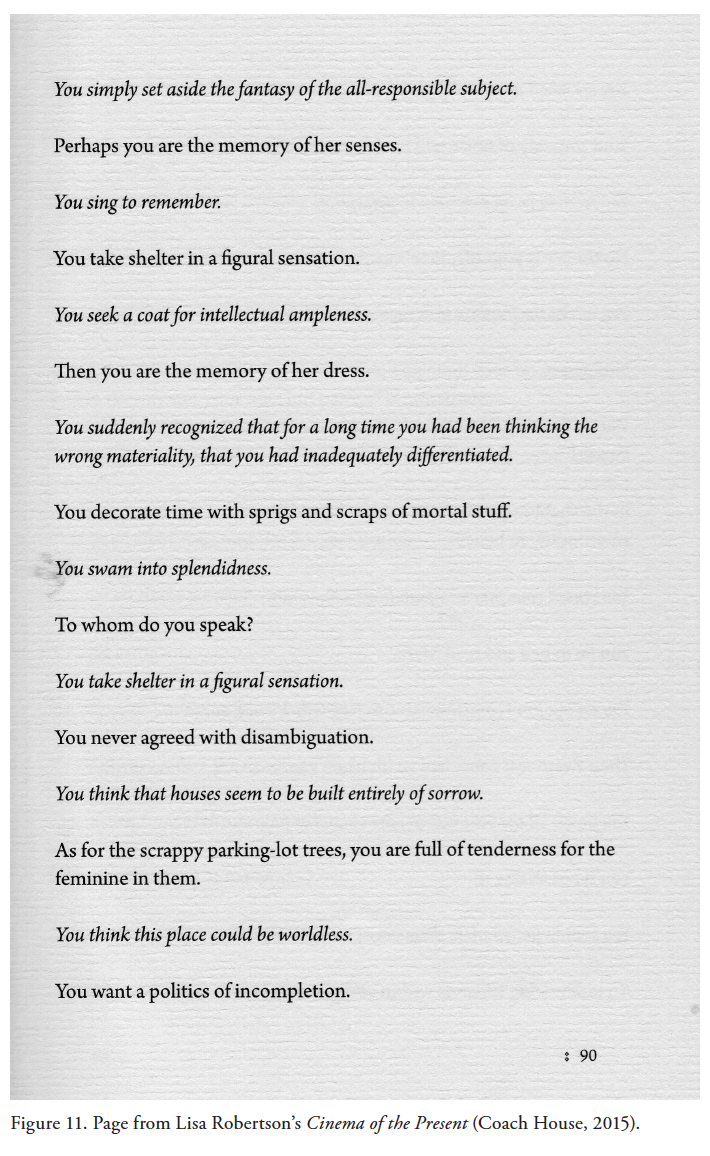

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1018 Robertson’s latest book, Cinema of the Present, is a kind of recursive cinema of language, displaying various types of sentences and pronoun functions for roughly a hundred pages, alternating italic and roman fonts, and mixing impersonal and personal statements, with the latter changing from a majority in the first person to a minority in the second. Some sentences, usually pages apart, contradict one another but in almost identical syntax and vocabulary. What the book “says” — if such a question can be asked about a book with such recalcitrant, non-explicit thematics — concerns language and poetic form and to some extent theories of conceptual poetry. Publishers Weekly reviewer Alex Crowley called the book “self-reflexive” — which it is, I suppose, if we understand Pope’s Essay on Criticism as self-reflexive. His “self-reflexive” seems to refer to the fact that numerous lines are systematically repeated in the poem rather than to the claim that there are instances when the poem discusses itself — which it doesn’t do. But Robertson’s poem does indirectly comment on its own poetics by discussing poetics, much the way that Pope’s Essay on Criticism also functions as a work of criticism. Her work, together with Bök’s, Jaeger’s, and Beaulieu’s, is a poetry that largely defies paraphrase, a poetry whose creators often perceive themselves as writing not only “against expression” but also against poetry that invites paraphrase. It is a poetry that is not an attempt at meaning, as in that staple of the undergraduate essay, “the poet is trying to say”; in McCaffery’s words, it is “prior to meaning.”13

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 1119 Neither Nichol nor Curnoe was ideologically “against expression,” but both were committed to, among other things, textual art in which words appear to resonate and communicate on their own rather than as person-specific utterances. Much the same can be said of Birney, Tourbin, Kearns, bissett, and Copithorne. It can also be said of current poets such as Gary Barwin and Kathryn Mockler, who have followed the ’pataphysical poetics pioneered in Canada by Nichol in The True Eventual Story of Billy the Kid and Truth: A Book of Fictions. Many contemporary visual and conceptual practitioners indeed tend to be “against” thematic or issue-based poetries and — like McCaffery — to divorce themselves from discursive poetries. Beaulieu writes in a recent manifesto that “poetry has become ruefully ensconced in the traditional. . . . [T]he vast majority of poets are trapped in the 20th (if not the 19th) century hopelessly reiterating tired tropes” ([3]). The echoes of Nichol’s 1971 visual poem manifesto — “poetry being at a dead end poetry is dead. . . . The poem will live again when we accept finally the fact of the poem’s death” (ABC passim) — here become bitter and contemptuous.14

20 Perhaps readers, historians, and anthologists should have taken more seriously Nichol’s puzzlement that poets continued to want to write a “dead” style of poetry, one that, as Easthope would soon observe, by the late twentieth century had little audience beyond that captive one of undergraduates. New art forms, after all, are much more than new fashions with which to make previous ones appear embarrassingly outmoded; they are the means by which art retains its cultural relevance and leverage and are — at least indirectly — of benefit to all who write. In that 1983 passage that I began this essay by quoting, Easthope declared that the poetry of the “single voice” was a residual phenomenon proper to Western bourgeois cultures of the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries and that non-discursive poetries would emerge as the canonical texts of our own periods. Perhaps that will become evident in the next forty years of Studies in Canadian Literature. At present, almost all of Easthope’s new poetry is confined in the United Kingdom to popular music, art gallery exhibitions, festival performances, and non-academic presses. Yet concurrently Christian Bök’s Eunoia was the top-selling book of poetry there for 2008 and on the Times list of that year’s top-10 books. Since 1997 three of Robertson’s books have been published there, publications which have led to her holding residencies at three British universities, including Cambridge. She has also had two poetry books published in the United States, one with the prestigious University of California Press, and another in French translation in France. Her books have been reviewed — like Bök’s and McCaffery’s — by major media such as the New York Times, Publishers Weekly, Jacket, and Chicago Review. Some of Bök’s, Beaulieu’s, and McCaffery’s books have also been published by significant US presses (see notes 4 and 13). But it would be difficult to discover that such places consider these writers among Canada’s leading contemporary poets by looking through the past decade of Canadian academic publications.