Articles

A Poetics of Simpson Pass:

Natural History and Place-Making in Rocky Mountains Park

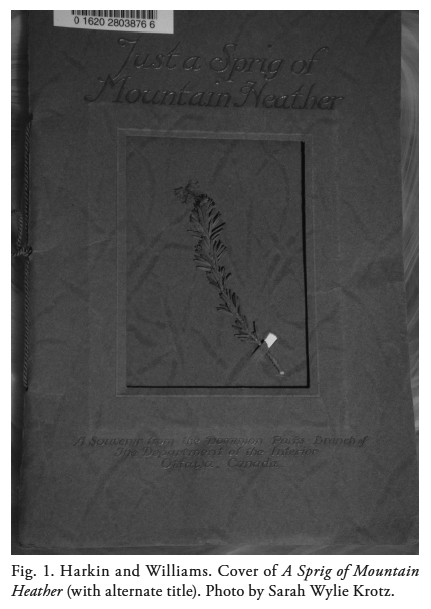

1 On 14 July 1913, Norman Sanson, meteorological observer and curator for the Banff Museum, and Abraham Knechtel, the Dominion Parks’ chief forester, climbed up to Simpson Pass in Rocky Mountains (now Banff) Park to gather armloads of heather. Some two thousand specimens were pressed and, a year later, placed in the covers of a run of pamphlets promoting Canada’s recently established Dominion Parks system.1 Published in 1914, A Sprig of Mountain Heather: Being a Story of the Heather and Some Facts About the Mountain Playgrounds of the Dominion was designed and written by James Bernard Harkin, the first commissioner for Canada’s Dominion Parks, in collaboration with Mabel Williams, his assistant in the Department of the Interior.2 E.J. Hart calls it a “totally unique publication” among park brochures and “perhaps the most interesting ever issued by the Parks Branch” (Harkin 79, 78). Part souvenir, part manifesto, it articulates Harkin’s philosophy concerning national parks. As its subtitle promises, it also tells “a story of the heather” that adorns its front cover. This story, and the connection that it forges between settler culture and the mountains, is the subject of my essay. Serving as a preamble to the more manifesto-like sections of the pamphlet, which address topics such as the “Commercial Side of Parks,” “Main Purposes Served,” “Refining Influence,” “Patriotic Influence,” and “Policy and Ideals” (8-12), the story of the heather couches the national project of park-creation in an intimate aesthetic and literary practice of natural history, with its peculiar poetics of place-making.

2 This diminutive alpine plant is perhaps not the first image that springs to mind when one thinks of the sublime landscapes of Banff or the Rocky Mountains today, when souvenirs are more likely to feature images of snow-covered peaks and bemused bighorn sheep. According to Sanson, the heather was selected over other flowers only because it proved the most suitable for pressing (1914: 27). Yet as the Toronto Globe noted at the time, it made for “‘a novel and effective way to capture the tourists’ interests in Canada’s national parks’” (qtd. in Hart, Harkin 81).3 Indeed, the heather proved a potent symbol with which to transform a remote geography on the fringes of the early Canadian spatial imaginary — a geography more readily associated with space than place — into an invitingly familiar landscape at the heart of it. At once a synecdoche of the mountain pass and a symbolic link to European culture, the pressed flower concentrates the longings of an emigrant society looking not just for recreation but also for meaningful imaginative connection to the land.

3 The opening lines of the pamphlet, for example, present the heather as a part of the place itself:

Capitalizing on an appreciation of “objects of nature as objects, as material possessions with all the satisfying virtues of the concrete” that characterized practices of natural history throughout the nineteenth century (Merrill 11), the authors fetishize the specimen as a concrete bearer of place and memory. The sprig of heather remains compelling for its physicality. A century after they were picked, the flowers are papery and brittle, with only a hint of red left in their delicate bells. Their green leaves have faded to brown. Nevertheless, to look upon this simple botanical offering is to feel an immediate and tangible link to the “sunny alpine garden, nearly a mile and a half above the sea”4 where it was gathered (Harkin 3). “[I]n very reality” a part of the pass, each flower carries traces of that summer in 1913: of the animals that brushed up against it, the insects that took shelter in its leaves, and, finally, the men who picked it and gently carried it down the mountainside to be transformed into a specimen and a story. As a physical object, then, the sprig of heather both augments and transcends the text in which it is embedded.

4 At the same time, no less than the decorative cover, this text frames our reading of the heather: its layered cultural and geographical narrative imbues the flower with a mnemonic resonance reflecting the desires of a settler society immersed in the work of inscribing the land in its own image. In 1914, Harkin and Williams were busy transforming the Rocky Mountains landscape into“a post-Confederation national icon, a place to visit to discover the heart of the country” (Sandilands 143). The story of the heather suggests that, in their minds, this process of place-making was as vital to the well-being of the nation as were the opportunities for “recreation in the out-of-doors” and “stimulating companionship with nature” that the parks provided (Harkin 7, 8). For many of the pamphlet’s intended readers, the mountains remained at the perceived edge not just of the Prairies but also of civilization as a whole. Describing her early work with the Parks Branch, which had been created only three years earlier (in 1911) and was housed in Ottawa, Williams remarked that “[t]hree thousand miles away from their inspiring reality, it was difficult to visualize these national parks”; although Harkin had travelled west (“to the great appreciation of those living and working there,” notes MacEachern), when Williams helped to put together this pamphlet in the Ottawa office, she had not yet laid eyes on the Rockies and the parks that she had been employed to promote (qtd. in MacEachern 26, 29, 35). A botanical specimen that you could hold in your hand, a synecdoche of the mountain pass, and a symbol of what the mountains might represent to such newcomers, the sprig of heather not only adorns but also informs the parks philosophy that the pamphlet articulates. With the pressed flower serving as the primary line of connection between prospective visitors and what, for most, remained a remote geographical region, the story of the heather affords a glimpse of the powerful role that natural history played, not only in the cultural reinvention of the alpine landscape but also in the imaginative appropriation of space in early Canada more broadly.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 15 Natural history in early Canada comprised a varied terrain ranging from individual, often amateur, efforts to far-reaching institutionalized studies such as The Geological Survey of Canada, founded in 1841 and renamed The Geological and Natural History Survey of Canada between 1879 and 1889, whose inventories highlighted increasingly vast regions for agriculture and resource exploitation. “Born of wonder and nurtured by greed,” as the historian Carl Berger puts it (3), the successes of natural history depended as much upon modest efforts as they did upon ambitious ones. As Suzanne Zeller observes, along with natural philosophy, natural history represented

Without claiming to be making anything more than a humble “piecemeal” contribution (this is “Just a Sprig of Mountain Heather” as the pamphlet’s cover suggests), Harkin and Williams offer the specimen as an addition to “the stock of knowledge” about the still young dominion: “It is just possible that some of you may not know that heather flourishes in Canada, and yet there are lofty slopes and plateaus in the Rockies and the Selkirks generously carpeted with heather like the hills and moors of Scotland” (3). In its invitation to discover a little-known feature of Canadian geography, A Sprig of Mountain Heather appeals to the spirit of exploration that animated nineteenth-century natural history as it worked to fill in the blank spaces of the map, especially in remote outposts of empire.

6 When Sanson and Knechtel gathered flowers on Simpson Pass, they were participating in a nineteenth-century practice of collection and description that cast settlers as explorers discovering, naming, ordering, and gaining scientific and aesthetic appreciation of the largely uncharted spaces of their adopted homes. At least since Gilbert White published his Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne in 1789, the close observation and description of nature has been equated with attachment to local environments. White’s model for exploring the flora and fauna of one’s immediate neighbourhood resonated with particular force in the colonies, his dictum “Every country needs its own monographer” inspiring newcomers such as Philip Henry Gosse, who used the line as the epigraph for The Canadian Naturalist (1840), and Catharine Parr Traill, for whom natural history, particularly botany, became a means of reading the land, most notably in her botanical studies Canadian Wild Flowers (1865) and Studies of Plant Life in Canada (1885). As Traill had remarked in 1832 upon emigrating from Suffolk to Upper Canada, “A settler upon first locating his lot knows no more of its boundaries or natural features than he does of the Northwest Passage” (Backwoods 161-62). Not only was the land unknown, but it also lacked mnemonic value: “Here,” Traill writes, “there are no historical associations, no legendary tales of those that come before us. Fancy would starve for lack of marvellous food to keep her alive in the backwoods” (128). In the opinion of John MacTaggart, the Scottish engineer hired to survey the Rideau Canal between 1826 and 1828, it was not just the fancy but also the whole moral and intellectual spirit that could starve in such an atmosphere. In his book Three Years in Canada (1829), MacTaggart arrived at the unfortunate conclusion that while “[t]he natural beauties of Canada” were “not to be matched in the world . . . her human population [was] composed of such materials, that to mingle with them is one of the severest punishments that can be inflicted on a feeling heart.” “The cause of this,” he concluded, “arises chiefly from droves of discontented people pouring annually into the country — people, who from stress of weather, or more often from bad behavior, are obliged to quit the mother shore” (204-05). Embodying the “forced homelessness of the reluctant emigrant, the displaced person, the involuntary exile,” the inhabitants of early Canada of whom MacTaggart writes fit cultural anthropologist Keith Basso’s definition of a people “adrift, literally dislocated, in unfamiliar surroundings [they] do not comprehend and care for even less” (Casey x; Basso xiii). When experienced as dislocation rather than relocation or transplantation, emigration to Canada involved succumbing to an acute condition of what Edward S. Casey describes as “placelessness” (x).

7 While MacTaggart mentions a number of diversions with which new residents of Canada could “counteract” the psychic discontent of emigration, his favourite solution was what he called “rummaging” (52). “If the mind can find nothing interesting, disease and every evil afflict both it and the body,” he observed, “but where it can find plenty of employment, dangers and difficulties are easily surmounted” (54). More than just an intellectual distraction, to “rummage” was to explore in search of interesting and wonderful stories, facts, and natural curiosities. It was to ask the kinds of questions of one’s immediate surroundings that MacTaggart posed to the public in the Montreal Herald “soon after [his] arrival in Canada,” questions that included “[w]hat are the names of the trees, briers, shrubs, plants, herbs, flowers, mosses, &c. which are or have been found in the country?” (170-72). “Let the reasons for such names be expounded, and their qualities told,” he declared, “let specimens of about six inches cube be obtained of each tree, and let the name be stamped on each; let the leaves be preserved in a book, and the berries in spirits of wine” (172). Building to an impassioned call for a “Society for the Promotion of Natural History,” which was established in Montreal shortly thereafter, with MacTaggart “unanimously elected a member” (177), he called attention to the connection between natural history and a sense of place. As if in answer to MacTaggart’s call, Traill amassed an impressive collection of natural specimens over the course of her long life in Ontario, reassuring her readers that “[if Canada’s] volume of history is yet blank, that of Nature is open” (Backwoods 129).

8 Sanson and Knechtel were not the first people of European descent to remark upon the heather growing on the alpine meadows of the Rocky Mountains, or even of Simpson Pass. In 1866, John Keast Lord, the naturalist for the British Columbia International Boundary Commission, identified the “heather-clad moorland” of the Rocky Mountains as one of the preferred habitats of the “hermit-like” dipper, who “loves to linger amidst the wildest solitudes of Nature” (56). By 1913, the most famous botanists associated with the mountain parks were Charles and Mary Schäffer, who had travelled to the Rockies from Philadelphia every summer for a decade to compile notes for their Alpine Flora of the Canadian Rocky Mountains, which Mary Schäffer completed with Stewardson Brown in 1907 after her husband’s death. The red mountain heather is described here in the cold, precise language of taxonomic identification and classification (217). Elsewhere, Schäffer distinguishes such dry botanical inventories from the leisurely, aesthetic practice of natural history that she advocated for tourists and mountain climbers in the parks (89). Nonetheless, identification is the foundation (and a significant part of the pleasure) of any natural history practice, and the Linnaean taxonomic order had “a deep and lasting impact not just on travel and travel writing, but on the overall ways European citizenries made, and made sense of, their place on the planet” (Pratt 24). Albeit briefly (their chief interest being symbolic rather than scientific identification), Harkin and Williams’s description of the heather and its related species situates national park Nature within this Linnaean taxonomic tradition (4-5). No less than the taxidermic specimens of mountain goats and birds, pinned butterflies, and mineral samples with which Sanson diligently filled the cases of the Banff Museum, the sprig of heather promotes a sense of nature as an orderly and knowable system.

9 According to Mark Simpson, the particular order that was being produced in the parks through practices of collecting and display during this period was as racially inflected as was the vision of national recreation that the pamphlet also promotes; it was an order “in which white men are the dispassionate masters — the curators — of an organically determined natural world” (88). Class, too, defined the practice of natural history. For visitors to the parks — an elite group, especially in the early days — natural history frequently went hand in hand with mountain climbing. The genteel American climber Walter Wilcox botanized on Simpson Pass during the first circumnavigation of Mt. Assiniboine in 1895, devoting part of his monumental narrative of the ascent to the “discover[y]” of “new varieties” of flowers “in every meadow, swamp, and grove” along the route (143). The Alpine Club of Canada, which “was established in 1906 to put Canadians on the mountaineering map,” institutionalized this combination of interests, attracting a “well-educated, articulate constituency” of Anglo-Canadian society that “shared an avid interest in natural history, the mountains, and climbing” (Reichwein 160, 162).5

10 Race, ethnicity, and class underwrite the way in which the story of the heather “curates” the botanical specimen and its symbolic value. According to Harkin and Williams, the ancestors of this particular sprig of heather were first discovered by “Sir George Simpson, Governor in Chief of the Hudson Bay Company, who traversed [the Pass] in 1841 in the course of his journey around the world” (3). As they recount,

In addition to perpetuating natural history’s association with imperial exploration, this recollection also simultaneously registers and begins to address the problem of history and place for settler society. For longtime inhabitants of a given “portion . . . of the earth,” argues cultural anthropologist Keith Basso, place and time fold in on one another, the land itself holding in its forms, contours, and names a memory of its history (4). In order to tap into the significance of place as “bearing on prior events,” he urges, we must “loosen” our “perceptions” and allow them to transport us to “the country of the past” (4). However, as Traill and MacTaggart (among many others) were wont to point out, for newcomers, the land is not mnemonic in the way that Basso outlines, hence the familiar trope of Canada’s “lack of ghosts” — the “only” thing, according to the poet Earle Birney, that truly “haunt[s]” us (447). The Canadian consciousness that Birney addresses is, needless to say, a settler consciousness forged by emigrants and their descendants — people like Traill and her sister, Susanna Moodie, for whom Canada appeared both too prosaic and “too new for ghosts” (Traill, Backwoods 128; Moodie 267). The mountains were no exception. As one early visitor put it, compared with “other mountain ranges of the world,” the Rockies seemed “at once beautiful and haunting by their emptiness” (Hart, Jimmy 48).

11 The story of the heather appeals to the visitor’s desire for a sense of history — of ghosts — in the mountains. Like the tree trunk into which Simpson carved his initials as he passed through what would then have been known as Shuswap Pass (for the First Nation that occupied its western slopes, likely using it to trade with the Stoney-Nakoda on the other side when relations were good) and indeed, like the renaming that followed,6 the story of the heather becomes a means of transforming alien space into mnemonic place. That Harkin and Williams elide the Indigenous history of this area only reveals more starkly the imperative of overwriting that defined the parks — at least in the official narratives — in these early days. As the cultural geographer Yi Fu Tuan reminds us, “There is far more to experience” in any given place “than those elements we choose to attend to. In large measure, culture dictates the focus and range of our awareness” (148).

12 One of the most striking aspects of the way in which Harkin and Williams historicize the heather and the mountain pass is also what tells us most clearly that it is not an Indigenous sensibility, but rather that of “the British exile,” that the pamphlet sought to nurture (Harkin 11). In Simpson’s account of the heather, the image of this particular part of Canada that has begun to crystallize dissolves into a recollection of the moors of Scotland. Even if the Red Mountain Heather is not “the genuine staple of the brown heaths of the ‘land o’ cakes,’” as Simpson puts it (3), the reminiscence that it occasions reveals the complex imaginative weaving of the local and the faraway in settler relationships to the land: if Simpson’s feet were firmly planted on the Pass, his mind was, at least momentarily, transported elsewhere. Natural history has long been bound up in this fabric of mnemonic geography. For all her desire to “foster a love for the native plants of Canada,” for instance, Traill also “long[ed] to introduce seeds from England” (Wild Flowers n. pag.; Backwoods 125) and delighted in the appearance of invasive species such as the Tall Buttercup (Ranunculusacris) for its ability to conjure her longed-for childhood home:

So potent is the natural object as a locus of memory that it symbolizes not just rootedness in place but also an uncanny transcendence of both time and geographical distance. Thus, in the final pages of Landscape and Memory, Simon Schama describes Henry David Thoreau coming upon “a spot so wild that the ‘huckleberries grew hairy and inedible.’” “The discovery,” Schama writes,

Just as Thoreau’s wilderness of huckleberries imaginatively transports him to another time (the early colonial history of Concord in “Squaw Sachem’s day”) and place (Labrador), Harkin and Williams’s heather is “a tiny link” that exceeds its local habitat. Yet whereas the one “saves” its discoverer “the trouble” of travelling from a settled hub to the fringes of settler space, the other transports readers from the fringes of empire closer to its centre.

13 “No people ever loved a flower as the Highlander loves his heather,” we read; “He honors the thistle as the emblem of Scotland, but the heather warms his heart. With its garlands he has crowned his heroes; it is interwoven with his songs and poems” (Harkin 5). Through a web of cultural allusions, Simpson Pass comes to signify not the terrain of Indigenous hunting grounds and vision quests,7 or even, ultimately, of European explorers’ journeys, but the literary landscape of Robert Burns, Robert Louis Stevenson, John Leyden, Sir Walter Scott, and Andrew Lang. The story of the mountain heather becomes the story of the Picts, who made liquor of rare and wonderful powers out of the plant, and of Bonnie Prince Charlie, who lay as a fugitive for three weeks on a bed of it in the Cave of Corragbroth (5-6). As I.S. MacLaren observes, the pamphlet’s epigraph, “Living flowers that skirt the eternal frost” (borrowed from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 1802 poem, “Hymn Before Sun-Rise, in the Vale of Chamouni”), “not only links the Rocky Mountain ‘playgrounds’ with one of the best-known tourist destinations in the French Alps but also colours them with the imagination of one of the foremost Romantic nature poets, thereby cultivating their nature as something wholly recognizable and admirable” (Mapper 152n). In addition to imbuing the New World landscape with imported cultural significance, such literary associations underscore that part of the restorative power and moral “uplift” that mountain parks could offer their visitors was a poetic sensibility cultivated by capital N Nature (Harkin 10). In the words of the famous nineteenth-century urban park designer Frederick Law Olmsted, “‘the charm of natural scenery tends to make us poets. There is a sensibility to poetic inspiration in every man of us, and its utter suppression means a sadly morbid condition. Poets, we may not be, but a little lifted out of our ordinary prose we may be often to our advantage” (qtd. in Bentley 177).8 Just as the aesthetic and symbolic value of the heather becomes part of the layered geographical, historical, and poetic significance of Simpson Pass, so too does it colour our sense of the parks as a whole, “culturing [their] wilderness,” to borrow MacLaren’s formulation,9 and thus negotiating the space between cultivated and wild, place and space.

14 Perhaps needless to say, the references to the Scottish Highlands and its literary heritage, which resonate the most strongly throughout the story of the heather, were directed to a particular audience. In fact, Harkin and Williams may have had a single illustrious visitor in mind: as MacLaren has remarked, the Edinburgh-born Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s heavily publicized visit to Jasper Park coincided with the publication of A Sprig of Mountain Heather (Mapper 104). While the pamphlet’s allusions to Picts and Bonnie Prince Charlie may have afforded Doyle considerable amusement, however, they are also symptomatic of a larger historical phenomenon in the Dominion, where the Scots had become such a dominant cultural force that they have been called “primary inventors of English Canada” (Coleman 5). There was, in fact, a dramatic surge in Scottish emigration to Canada in the decade prior to the pamphlet’s publication: between 1901 and 1914, “nearly 170,000 Scots arrived at Canadian ports — about 65 per cent as many as the estimated total for the previous century” (Campey 5). Emphasizing the geographical distribution of the plant and its relationship to “the European species” of which it is “a very close relative,” the story of the heather offers to these emigrants a sign that they might similarly thrive and proliferate in the New World, with the comfort of reminiscences of home as tangible as the sprig of heather that they could now hold in their hand (Harkin 4).

15 Natural history played an important role in the process of colonial accommodation and appropriation, serving settler society on the one hand as a means of forging an aesthetic, intellectual, and spiritual attachment to adopted homes and, on the other, as a method of identifying and securing possession of valuable resources.10 Both registers are operative in Harkin’s pamphlet, which argues for the economic as well as the moral and recreational value of parks, and impresses upon the reader that — much like the botanical specimen now in their possession — “these parks are your parks, and all the wealth of beauty and opportunity for enjoyment which they offer are yours by right and heritage because you are Canadian” (7-8; emphasis added). This “right and heritage” had only recently been established.In 1877, the terms of Treaty Seven restricted Blackfoot, Peigan, Blood, Tsuu T’ina (Sarcee), and Stoney access to the mountains, although the Stoney-Nakoda continued to hunt on the eastern slopes after relocating to their reserve at Morley, Alberta. Their use of the mountain ranges, however, was further curtailed after Rocky Mountains Park was created.11 In These Mountains Are Our Sacred Places,Chief John Snow underscores the material and spiritual losses wrought by the displacement of the Stoney, who found their lives and livelihoods redefined by the park boundaries. He recalls that in the early days of colonial settlement, the Europeans “were described as ants on an ant hill because there were so many of them” (34). In 1907, Chief Peter Wesley and Chief Moses Bearspaw of Morley could already complain, “‘our hunting grounds are covered with the houses and fences of white men’” (qtd. in Binnema and Niemi 737). In light of such descriptions, we might imagine Sanson and Knechtel from the perspective of the Stoney as just two more “ants” penetrating the mountains to carry off their treasures.

16 The rhetoric of possession that undergirds natural histories such as Schäffer’s “Haunts of the Wild Flowers of the Canadian Rockies (Within Reach of the Canadian Pacific Railroad),” an article that appeared in the “Botanical Notes” section of The Canadian Alpine Journal in 1911, both reinforces and regulates the settler’s growing sense of ownership of the parks. Directed at “the stranger, who once within the gates, is a stranger no longer,” the revelation of “[her] secret haunts,” including one spot “lovingly called ‘our garden’” justifies the “hard trudge” of a climb with the reward not just of the flowers themselves but also of privileged admittance to a secret club (92, 90). Her reluctance to disclose these haunts, and her instructions to her readers to “respect the rights of the flowers and not slaughter them,” conveys the extent to which the botanist assumed the role of guardian of a fragile part of the mountain ecosystem, that “right and heritage” came with a responsibility to protect (89).

17 Reading the story of the heather in the context of colonial appropriation helps us to recognize the limits of its particular inscription of place. Hikers can find a much different, and in many ways richer, elaboration of Simpson Pass in recent guides such as Sanford and Beck’s Historic Hikes around Mount Assiniboine and in Kananaskis Country (2010), which includes historical layers that Harkin’s promotional pamphlet does not. Overwriting, rather than archaeology, is the operative metaphor in A Sprig of Mountain Heather, which reveals as much about the culture that was recreating the significance of the Rocky Mountains as it does about the geography that inspired it. If Harkin and Williams distance this landscape from its contentious history of colonial appropriation, they equally elide its contemporary meaning to mountain men such as the legendary guide Bill Peyto, who spent several summers in a log cabin on the edge of the pass — he was living there when Sanson and Knechtel set up their flower pressing operation in 1913 (indeed, “A. Knechtel” appears to have taken a photograph of him on the Pass that summer).12A Sprig of Mountain Heather makes no mention of Peyto in its description of the Pass, despite the fact that genteel travellers like the aforementioned Walter Wilcox were drawn to the image of the mountains that such men embodied. According to Wilcox, “Peyto made an ideal picture of the wild west,” the figure that he cut astride his “Indian steed” — complete with “a buckskin shirt . . . and cartridge belt holding a hunting knife and a six-shooter” — adding considerably to the “romance of visiting this wild and interesting region, hitherto but little explored” (140, 137). For Peyto, the Rockies represented the antithesis of Europe: “Canada,” he writes in his journal, “is everything that dear old England isn’t — freedom to roam in these beautiful hills seeing no one but wild things, freedom to say what’s on a bloke’s mind without looking over his shoulder, and freedom to earn a grubstake by using brains and wits instead of depending on one’s station of birth” (Hart, Ain’t 11).

18 The story of the heather appeals less to its readers’ longing for New World freedom and wild adventures than it does to their taste for more cultivated pleasures that might make the New World seem contiguous with the Old. As the botanical descriptions that punctuate Wilcox’s Camping in the Canadian Rockies suggest, natural history (especially botany, which did not require a hunting rifle) counterbalanced the rougher side of mountaineering. His account of coming upon “the small and beautiful, purple Calypso” orchid “rearing its showy blossom a few inches above the ground” on the route through Simpson Pass attests that part of the thrill of mountain exploration lay in discovering rare species of flowers in the meadows and valleys that the great hulking peaks dwarfed (143). “We were very pleased to find this elegant and rare orchid growing so abundantly here,” he writes; “[t]here is a certain regal nobility and elegance pertaining to the whole family of orchids, which elevates them above all plants, and places them nearest to animate creation” (143-44). Wilcox delights in the discovery of the orchid not just because it is rare, but also because its peculiar beauty introduces connotations of “nobility and elegance” into the scene of “meadow, swamp, and grove” — connotations that, making the orchid “nearest to animate creation,” subtly yet powerfully humanize a landscape in which one could, as Peyto puts it, see “no one but wild things.” Stopping to examine and describe the intricate features of this flower, Wilcox not only humanizes but also creates a landmark in a topography that could seem overwhelmingly immense and in need of definition. “When seen from high altitudes,” he later explains, “a mountain appears merely as a part of a vast panorama or a single element in a wild, limitless scene of desolate peaks, which raise their bare, bleak summits among the sea of mountains far up into the cold regions of the atmosphere, where they become white with eternal snow, and bound by rigid glaciers” (185). With “no detailed maps covering this region that [were] entirely satisfactory,” the Rockies appear to the newcomer as the epitome of what Tuan calls “amorphous space” — a space that the naturalist helped to transform into “articulated geography” (iv; Tuan 83).

19 Tuan defines space and place in opposition to one another: space is amorphous; place is articulated; the one is movement, the other, “pause” (6). Place is space that is “filled with meaning”; conceptually if not also literally, place is “enclosed and humanized” (199; Westphal 5). As Wilcox demonstrates, natural history is a practice that stops you in your tracks; whether focusing on an orchid or a sprig of heather, the naturalist creates “a landmark upon which the eye pauses when it surveys a general scene, ‘a point of rest’” in “an area of freedom and mobility” (Westphal 5). Interrupting the narrative of his ascent to Mt. Assiniboine, Wilcox’s careful attention to the orchid enacts the very kind of “pause in movement” that “makes it possible for a locality to become a center of felt value,” and thus to become place (Tuan 138).

20 For those who brave the summits of the mountains, the “felt value” of plants marks a landscape of contrasts. A number of climbers have perceived the alpine meadow of Simpson Pass as a living counterpoint to the “desolate peaks” and “bare, bleak summits” of the Rockies. In many accounts, this is the last inviting landscape on the ascent to the forbidding peak of Mt. Assiniboine. The British climber Sir James Outram underscores the experience in the language of the picturesque and the sublime. He describes following “a steep pathway . . . through thick firs up a narrow rocky canyon till we arrived in a beautiful open park,” where

Drawing from the pictorial economy of the picturesque, Outram locates features of the landscape “here and there, and on either hand” in a way that highlights both the variety and the pleasing arrangement of colours and textures in this park-like scene. The lush vegetation of the meadow stands in stark contrast with the “dreary silence and strange scarcity of living things” that he remarks are a “notable characteristic of the Canadian Cordilleras” (33). From the “barren and boulder-strewn” valley at the source of the Simpson River, to the “strange barrier ridges” and “the rock-bound basin . . . hemmed in by gray, ruined towers, from which the wide belts and tapering tongues of tumbled scree streamed down among the bare poles of the stricken pines, with a tiny tarn, sombre and forbidding, in its depths” (32, 33), Outram’s description of the route becomes increasingly marked by sublime terror, culminating with Mt. Assiniboine “ris[ing], like a monster tooth, from an entourage of dark cliff and gleaming glacier” (33).

21 Juxtaposed with this forbidding landscape, A Sprig of Mountain Heather illustrates the significance of the mountain parks as an extension of the domestic, civilized space of the nation.13 Growing where “[t]he distribution of . . . woods, shrubbery, trees, ponds, streams and moss-covered boulders is so harmonious that it produces the impression of an artificial park,” the heather serves as a reminder that even Canada’s most remote and wild places contain “veritable flower gardens” — “enclosed and humanized” places that offer relief from the vast, wild spaces of the mountains (6). Likened to a garden or artificial park, Simpson Pass emerges as Nature’s equivalent to the cultivated and refined luxuries that Banff Springs Hotel had been offering to tourists since it opened in 1888. Catriona Sandilands’s observation that such luxury accommodations made it possible for “the elite to climb . . . along the nation’s mythic edge” and then, “in the soft light of the evening, . . . drink sherry and soak in the hot, therapeutic mineral water of civilization, now piped conveniently to various bathhouses” draws attention to the dialectic between space and place (which is gendered as well as classed) that underpins the idea of the national park (144). In Tuan’s words, “[p]lace is security, space is freedom: we are attached to the one and long for the other” (3). As “[l]iving flowers that skirt the eternal frost,” the heather in Harkin and Williams’s pamphlet establishes the parks as a liminal zone where place and space, embodied by picturesque meadow and sublime peak, meet. The geographical phenomenon that allows the visitor “to stand one foot in the snow, the other on living flowers” symbolizes how the authors sought to satisfy the desire for both place and space (7).

22 Simpson Pass is a border space par excellence. Straddling the continental divide, it follows the height of land that separates watersheds, First Nations, and, more recently, the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia. If the great hulking masses of limestone cliff and sedimentary slope that characterize the Rocky Mountains are an archive of plate tectonics, where geologists can trace the earth-shattering collision between the deep past and the present, Simpson Pass, sitting half-hidden, a quiet interval between them, evokes the less literally earth-shattering, but nonetheless powerful, ways in which the arrival of Europeans in the Americas also reshaped landscapes and ecosystems, altering them physically, demographically, and imaginatively. Indicative of the profound and widespread imaginative transformation of Indigenous territories and wilderness into a place marked everywhere — even in the pressed leaves of a botanical specimen — with the signs of an Anglo-Canadian culture that was being defined in the east, A Sprig of Mountain Heather helps to define the Pass — and, by extension, the parks themselves — as a landscape in which it is possible to negotiate, not just between the snowy, barren peaks and the lush, fertile tree line, but also between categories such as sublime and picturesque, wild and civilized, masculine and feminine, space and place, and, indeed, Canada and Europe.

Thanks are due to the archivists at the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies for their kind research assistance; to Eric Adams, Brian Pettitt, and Liza Piper for commenting on drafts of the essay; to my anonymous reviewers for their helpful insights; and to Ian MacLaren for showing me this fascinating pamphlet in the first place. Early versions of this essay were presented at the ALECC conference in Kelowna, British Columbia, in 2012 and at the Canadian Mountain Studies Initiative at the University of Alberta in 2013.