Articles

Protecting Her Brand:

Contextualizing the Production and Publication of L.M. Montgomery’s “The Alpine Path”

1 With the publication of Anne of Green Gables in 1908, L.M. Montgomery experienced a sudden surge of public interest in her private life. In a journal entry dated 10 November 1908, she wrote: “I had a letter to-day from a Toronto journalist who had been detailed to write a special article about me for his paper — wants to know all about my birth, education, early life, when and how I began to write etc.” Somewhat begrudgingly she accedes to his wish but on her own terms: “Well, I’ll give him the bare facts he wants. He will not know any more about the real me or my real life for it all, nor will his readers” (SJLMM 1: 342). Although Montgomery never quite shook her reluctance to render up her private life for mass consumption, the rising tide of human-interest journalism and celebrity profiling in the early twentieth-century periodical press made it necessary for her to generate a more nuanced response to the demands of the media and her fans. Over time, and somewhat at the prodding of both her publisher and the press, Montgomery learned how to craft a public identity that could be mobilized when necessary to satisfy the public appetite to “know all.” This public image was conservative, domestic, and feminine, and it was well-received by the media and her fans who used it, promoted it, and even added to it with their own observations and embellishments. Firmly tied to her domestic fiction and buttressed by dominant constructions of genteel femininity, the persuasive brand that Montgomery had created came to be a cornerstone of her public identity.

2 One of the more significant and substantial interventions Montgomery made into the production and dissemination of her public image and brand in Canada was the publication of a memoir in 1917. “The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career,” originally serialized over six installments in Everywoman’s World magazine, was Montgomery’s longest, most detailed public representation of her life and career.1 While the conditions of its publication prevented the memoir from circulating as widely as her novels, “The Alpine Path” nevertheless offers us some insight into the brand Montgomery was cultivating. As we shall see, the text has strong ties to Montgomery’s other media strategies and builds upon information and narratives already in circulation, but it also bears the traces of her reluctant and cagey engagement with the demands that she “throw open the portals of sacred shrines to the gaze of the crowd” (SJLMM 2: 202). Narratives about her domestic life are conspicuously absent, but Montgomery’s refusal to narrate this portion of her life does not undermine her brand; in fact, it is on the strength of that brand that Montgomery is able to write and publish this text as she does. As an investigation of the contexts of the production and publication of “The Alpine Path” reveals, the memoir both invokes and affirms the public image Montgomery had already put into play. It is through her previous media work and the text’s publication in a domestic magazine that her audience could make sense of the vague domestic signals and fill certain gaps and silences with conventional gender scripts. Remobilizing the human-interest journalism she so reluctantly participated in, Montgomery allows the brand to speak where she will not, and the result is a public autobiography that implicates but does not narrate her private life and domestic identity.

3 In the first few decades of the twentieth century, human-interest journalism in Canada was on the rise and those men and women whose cultural products circulated widely in the new mass markets found that they, too, had become objects of interest for mass consumption. Although profiles of the famous had long been part of periodical culture, changing trends in representation now favoured intimate and realistic over hagiographic portraits (Ponce de Leon 33-34, 61). As Charles Ponce de Leon has demonstrated, a realistic and authentic profile was increasingly contingent upon accessing and representing the individual’s private life, where, it was believed, the “real” person could be found (42-75). In this cultural climate, Montgomery’s attempt to pawn off reporters with just “the bare facts” was doomed to fail.

4 In Benjamin Lefebvre’s compendium of media articles on Montgomery in the L.M. Montgomery Reader, it appears that, for the first year or two after the publication of Anne of Green Gables, Montgomery could and did restrict the flow of information about her. As Lefebvre notes, she kept the focus on her “writing life” and masked the more personal details: one 1908 article in the Boston Journal even obscures her gender (“Introduction” 8). In 1909, we see her continuing to resist the pressure to reveal herself: in response to her publisher’s anxious request for a new photograph, she writes in her journal, “I hardly think it so very ‘urgent and important’ that the great American public should see my face” (SJLMM 1: 348). However, as the journals attest, the volume and frequency of requests for information on Montgomery only increased, and although she composed a stock retort of “‘information’ regarding my childhood and ‘career’” for distribution in January 1910, this did not close the door on public interest or speculation (SJLMM 1: 368). Later that same year in Boston, interviewers probed deeper, eliciting information about her rural life in Prince Edward Island, her living arrangements with her grandmother, and her opinions on Boston, suffrage, and women’s domestic responsibilities.2 Not only did these articles expand the scope of public knowledge about Montgomery well beyond tales of “childhood and career,” but also their preoccupation with her physical appearance soon became a staple component of most Montgomery profiles.

5 Neither press nor publishers, it seemed, could be satisfied with the kind of distance and anonymity Montgomery seemed to crave, and so, in this first decade of her celebrity, we see a public image and public relations strategy emerging. Wherever possible, Montgomery attempted to keep the gaze on her writing, but it was a strategy that worked best if she was the author of the article. Such a narrow scope was not sustainable in interviews where reporters increasingly needed to showcase their intimacy with their subject, which they did with Montgomery by describing her appearance and the setting of the interview and by asking questions unrelated to her writing career.3 As the Boston interviews reveal, Montgomery was already crafting a public identity for those situations, an identity steeped in conventional constructions of domestic femininity that were, as Lefebvre notes, occasionally more conservative about gender roles than she had articulated in private (“Introduction” 9). It was, however, an eminently sensible posture to strike: not only did it coalesce nicely with the domestic worlds of her fiction, lending her and, in turn, her texts legitimacy and authority, but it was a very safe and sensible image to cultivate in a culture still heavily invested in traditional gender roles.4 It was also a very marketable image: as Holly Pike has observed regarding the media material in Montgomery’s scrapbooks, “advertising surrounding Montgomery consistently focused on pastoral aspects of her work and life, her dainty physical appearance, and her domesticity. The marketing strategy was to present her as a suitable companion and guide for the young women and girls who were her readers” (245).

6 As her personal life changed, this portrait evolved to include Montgomery as a contented wife and doting mother who, Karr suggests, “[saw the] need for public-spirited women, [but] preferred to devote herself to home and family” (125). After 1911, we see media articles foregrounding Montgomery’s domestic identity as “Mrs. Ewan Macdonald, a charming wife and mother,” and some even printed Montgomery’s personal family photographs and signalled an intimate familiarity with the details of Montgomery’s home (MacMurchy, “L.M. Montgomery” 185). One 1914 article in the Toronto Star Weekly, for example, takes readers into the manse in Leaskdale to tell tales of “Punchkins,” the new baby; Montgomery’s cat; and family heirlooms (MacMurchy, “Anne” 190-94). Accompanying such stories are photographs of the home where Montgomery was married and of her son, Chester, with the cat (Heilbron 253).

7 While some of these more intimate portraits of Montgomery’s private life were written by a journalist friend (Heilbron 253), and others seem to posture an intimacy with, or proximity to the author, they did not likely have, there is much evidence to suggest that Montgomery not only began to co-operate with journalists — granting interviews and carefully choosing and staging photographs — but that she was also taking an active role in promoting a particular construction of her private life.5 The details of this life were still carefully monitored — as Montgomery writes in her journal, she was not ready to reveal to her fans “the dusty, ashcovered Cinderella of the furnace cellar” (SJLMM 2: 374) or the drudgery of everyday domesticity — but an idealized portrait of her life in the private sphere was becoming a strategic part of her public identity. Yet, unlike her explicit documentation of her writing life, this domestic identity was far more covertly performed: although she rarely offered explicit narratives of her life as wife and mother, she was routinely quoted or summarized as espousing that a woman’s primary place is in the home. Moreover, the contexts within which she conducted her interviews — at home, on her honeymoon, etc. — and the photographs she provided to reporters were clearly designed to showcase that she practised what she preached; she just left it to the journalists to narrate that portion of her life. A brand was forming — one based on Montgomery’s own revelations about her writing and her performances of genteel femininity, but also significantly shaped by the human-interest journalism that observed, documented, or, at times, invented descriptions and narratives that would satisfy the reader’s desire to know the “real” Montgomery.

8 Strategically, then, for Montgomery to produce a memoir that confirmed and consolidated her existing public image and legitimized the conservative worldview of both her texts and her readers made sense, and “The Alpine Path” does appear to fulfill most of these functions. The memoir opens conventionally enough with an invocation of the circumstances that compel her to write and a tracing of her family lineage on Prince Edward Island. By the end of the first installment (June 1917), she has begun to offer anecdotes of her halcyon childhood, memories that grow more narratively coherent as she ages. In total, roughly half of “The Alpine Path” is given over to these narratives that, we are meant to glean, later became the foundation or sites of inspiration for some of her poetry and fiction. In the third installment (Aug. 1917), the pace changes, and we move quickly from a meandering history of influence and inspiration to a speedy account of the practical application of her experiences and skill: in just a few paragraphs, we cover her first public performance at age nine to a growing list of publications and her career as a school teacher.

9 By the fourth installment (Sept. 1917), the style and format of the text shift dramatically as Montgomery relies more and more heavily on extensive quotation from her journals (the exception being a brief section on the experience of writing and publishing Anne of Green Gables). Equally puzzling as this shift in format is the conspicuous change in content halfway into the fifth installment (Oct. 1917): where narratives had, hitherto, been closely related to either the influence or pursuit of her literary career, the remainder of this and the following, final installment turn into a travelogue of Montgomery’s honeymoon in the UK. In the final paragraphs, her literary accomplishments since her honeymoon are quickly summed up, and she concludes with lofty sentiments borrowed from Keats’s Endymion that rationalize literary “immortality” as the product of hard work and sacrifice.

10 In most respects, “The Alpine Path” harmonizes nicely with both Montgomery’s fiction and what her audience likely already knew about her: the emphasis on her childhood in Prince Edward Island and its relatively pastoral representation functions as both a source for and a validation of her creative work. Responding to the burgeoning “Anne industry” in Cavendish, she clarifies which Cavendish landmarks correctly correspond to which spaces in Anne and, in addition to explicitly citing sources for particular stories, she implicitly encourages readers to see connections between her own childhood and Anne’s (she even justifies Anne’s “precocity” by tracing its roots in her own childhood sentiments). Even the narrating “I” — a good-humoured, genteel lady who both appreciates the absurdities and passions that govern the young and warmly encourages education and hard work — seems designed to remind us of Anne’s narrator. The text’s histories of self, family, and writing are also very much in alignment with what had previously circulated in the media — in fact, significant sections of “The Alpine Path” repeat almost verbatim certain anecdotes and stories already published in other interviews and profiles, no doubt a strategic and efficient ploy to ensure consistency in her image and respond to the market’s appetite for narrative without having to actually offer more than already in circulation.6

11 If “The Alpine Path” seems intent on being consistent with the information and public persona already disseminated, it is also quite obviously an incomplete accounting. The information provided confirms only a portion of what her audience might know or might expect to learn about Montgomery: of the development of the writer, much is provided, but of the production of Montgomery as a domestic creature, specifically as a wife and mother, there is nothing. There are no narratives of her childhood that reveal any inclination for the domestic arts; all interests, skills, and ambition are focused on anticipating her future work as a writer. Of Montgomery’s adult life in domestic spaces, we are told very little, and of her considerable labour in this sphere, we hear nothing. Without warning, we are told that she married but not to whom or why, and the indifference with which this event is narrated is strikingly out of character for the otherwise vibrant and engaged narrator: “In the winter of 1911, Grandmother Macneill died at the age of eighty-seven, and the old home was broken up. I stayed at Park Corner until July; and on July 5th was married” (Oct. 1917: 8).

12 The suddenness of Ewan Macdonald’s appearance in her memoir is in keeping with Montgomery’s tactics for integrating him into her other life writing texts (in her private journals, he also similarly just “appears”); moreover, according to Christine Etherington-Wright, the “appearance” of a fiancée as a fait accompli is a fairly typical convention of early twentieth-century women’s memoirs (150). However, all we learn of Macdonald in “The Alpine Path” is that his employment as a pastor in Ontario was the impetus for Montgomery’s move from her beloved Prince Edward Island; otherwise, he remains unnamed and unnarrated, an absence that becomes increasingly conspicuous when the end of “The Alpine Path” is dedicated to their honeymoon. This account of the honeymoon seems particularly detached for an author with a reputation for romantic fiction — not only is it devoid of emotional or romantic content and rendered in travelogue fragments (making it easier for Montgomery to write Macdonald out of the text), but she even also mistakes the date of their trip by an entire year. Of life after the honeymoon, “The Alpine Path” is silent, offering only a list of the books she has written in the six years since. Into that stretch of time, Montgomery might have written of her delight in finally becoming a mother, of her children and married life, or even her work in the church and community, but she does not, refusing the most obvious opportunities to inscribe a domestic plot into the story of her life.

13 In short, not only is the life story that explains her domestic public identity entirely absent from the text of “The Alpine Path,” but Montgomery’s readers also could have (and would have) learned more about her life since the success of Anne of Green Gables from the average biographical portrait in a newspaper or magazine than they would have by reading her memoir. Montgomery denies her readers the story of what it is like to be a famous woman and, more importantly, a famous woman who was also a wife and mother, and provides, instead, the narrative of the making of her career.7 Yet, in light of Montgomery’s previous media strategies when she, and not a reporter, held the pen, the scope of “The Alpine Path” is not surprising: while a narrative of the intimacies of her private life would have no doubt been eagerly consumed by readers, it would have been strikingly out of character for Montgomery. Although she does not narrate her domestic or private life, “The Alpine Path” finds alternative means to inscribe if not a specific domestic life, certainly an adherence to traditional gender roles that invoke and affirm the legitimacy of her public image and brand. There are, for example, some strategic omissions in the content of “The Alpine Path” that allow Montgomery to preserve her reputation as a “lady” author and advocate of domestic femininity. Montgomery’s refusal to narrate her current experience of fame, for example, helps to protect her domestic, rural brand from the effects of nine years of mass-market international fame. By narrating only the labour that built the career and not her experience of celebrity and success, the memoir hermetically seals her off from the unsalutary effects that fame was believed to have on both individuals and their labour.8 The fruits of that success are also absent: by remaining silent on the subject of how one might take a European honeymoon or run a household on a pastor’s salary, Montgomery allows the audience’s assumptions to supply a narrative that enables both husband and wife to assume roles more befitting traditional gender scripts.

14 “The Alpine Path” further implicates and builds on Montgomery’s brand as an advocate of conventional domesticity through its representation of — or, more accurately, its failure to represent — how she balanced her domestic work while nurturing a writing career at the same time. As we can see in the opening of the fourth installment, the absence of such narratives suggests that there is nothing remarkable or strenuous about managing both at once: “Grandfather died in 1898 and Grandmother was left alone in the old homestead. So I gave up teaching and stayed home with her. By 1901 I was beginning to make a ‘livable’ income for myself by my pen” (Sept. 1917: 8). Of the domestic labour that occupied her from 1898 to 1901, we are told nothing as if to signal that domestic labour is neither real work nor did it imperil her creative powers. Into this silence, readers are invited to remember the fate of Anne Shirley at the end of Anne of Green Gables. Like Montgomery, Anne must give up her teaching career when Matthew dies and return home to be with Marilla, but it is a sacrifice that is both proper and filled with its own domestic rewards:

While Anne appears resigned and contented by this turn of events, it is significant that the narrator of the novel articulates what Anne (and Montgomery in “The Alpine Path”) cannot — a kind of mourning for a lost career and closing horizons. The promise of fulfillment from domestic labour is offered as a kind of compensation but, more importantly, this “path” does not preclude or prohibit that natural impulse toward creative work. Moreover, this imagery of paths and flowers further encourages the audience of “The Alpine Path” to read parallels between Anne’s experience and Montgomery’s and to inscribe a contentment with domesticity that Montgomery could not or would not (we know from her journals that the abandonment of her teaching career and her return home was marked by unhappiness and depression).9 Fans would know that for Montgomery, like Anne, that “bend in the road” signals further career prospects and marriage.

15 In contrast to the unspoken but implied harmony between domesticity and writing, Montgomery is quite explicit in “The Alpine Path” that labour performed outside of the house is affected by domestic obligations; just as her teaching career must be abandoned upon the death of her grandfather, she acknowledges the difficulty she had maintaining her writing career while working outside the home. We linger with Montgomery in her memories of trying to write in the bitterly cold hours before the teaching day began, and we are made to feel the exhaustion that attends copy editing, especially when evenings must be given over to “keep my buttons sewed on and my stockings darned” and moments to write stolen during work hours (Sept. 1917: 8). What Montgomery represents (and fails to represent) suggests an implicit critique of women’s labour outside of the home: her previous jobs clearly affected her ability to write or had to be abandoned in order to attend to family duty. In rehearsing some of the common criticisms of the dangers of women working outside the home, “The Alpine Path” signals Montgomery’s conservative politics and, more importantly, protects her own career from being implicated in these arguments. The absence of narratives about domestic labour and a writing career implicitly suggests that the labour performed in one arena will not affect or encroach upon the labour in another, an argument she made more explicitly in other media interviews and articles.10

16 Not all of Montgomery’s attempts to avoid narrating her private domestic life work quite so seamlessly. Part way through the fifth installment, the memoir conspicuously shifts its form and content from narratives of her career to journal entries from her honeymoon; however, a strict frugality still governs Montgomery’s representation of this private life. These are restrained, even dull, travel entries that perform a kind of vague domesticity while evading personal detail. Ewan Macdonald is noticeably absent from these honeymoon entries, but this is an absence that is legitimized, in some respects, by the shift in form: one expects to find gaps in travelogues and journal writing, particularly when it is clear that only excerpts are being represented. Journal entries also allow Montgomery to avoid the teleological impulse of retrospective narrative — she does not need to make the honeymoon or the travel speak to, or culminate in, a particular point because the entries can stand as accounts of isolated incidents from the past. Yet, without this impulse, these entries also appear directionless: they cannot be recuperated into the “alpine path” construct of her writing career, for success and “arrival” occurred several years before marriage, nor is there a clear association between her experiences travelling and the content of subsequent novels.

17 This unusual (and unexpected) turn in the content and form of her memoir bears the traces of Montgomery’s conflicted concessions to her audience and her editors. In some respects, Montgomery couldn’t remain silent on the subject of her marriage: an allusion to her role as a wife was not only a critical component of her brand but also necessary for bringing the content of “The Alpine Path” in alignment with other versions of her life already circulating in the media. We also know that Montgomery was under some pressure to perform more of her private life, particularly her love life, from the editor of Everywoman’s World:

The editor’s interest in a narrative of “pangs and passions” stems not from a desire to provide a comprehensive portrait of Montgomery’s life but to capture the greatest market share possible for the magazine and, perhaps, to further integrate Montgomery’s text into the magazine’s domestic mandate. It is significant that he does not anticipate such narratives would run counter to the magazine and Montgomery’s middleclass domestic brand, whereas Montgomery is justifiably apprehensive about the impact of Herman Leard and Ed Simpson stories (represented in the journals but excised from the above quotation). Throughout her memoir, Montgomery frequently transforms unpleasant memories into pastoral narratives of delight, and though she may have refused to turn Leard or Simpson into narrative fodder, one might read the honeymoon entries as an extension of that project. Hence, even though Ewan remains unnarrated, his presence on that trip and, therein, Montgomery’s domestic identity is certainly implied.

18 The reader searching her memoir for an explicit inscription of Montgomery’s domestic life will not find it — much depends on the reader to read this identity into the text’s gaps and silences — but in the memoir’s original publication in Everywoman’s World, the domestic world is unavoidable. Not only is the memoir literally woven between advertisements for face creams and foot ointments and editorials on child rearing and house chores, but also an extra-textual domestic frame has been consciously crafted by both Montgomery and the editors. Over the six issues in which Montgomery’s memoir appears (June to November 1917), articles, editorial commentary, and advertisements were designed to support and, in some cases, recontextualize the content of the text; moreover, photographs from Montgomery’s personal collection, with captions often in the first person, frame the opening page of each installment. These features, missing from both the 1974 Fitzhenry & Whiteside and the 2005 Nimbus editions of The Alpine Path, change how we read the text and how we understand its role in affirming and crafting Montgomery’s public image.

19 Although, as her journal bears out, Montgomery and the editors of Everywoman’s World did not always have the same vision for the scope of her life story, it nevertheless made perfect sense for Montgomery to produce a memoir and for the periodical to pay handsomely for the privilege of serializing it: Everywoman’s World was a Canadian magazine whose branding was perfectly aligned with the public image that Montgomery had hitherto crafted. Created in 1914 as a vehicle for more effective advertising of Canadian products to Canadian audiences, Everywoman’s World was entirely focused on marketing to women who, it was believed, made the vast majority of purchasing decisions on domestic items (Johnston, Selling Themselves 240). The magazine carried much the same content as its American counterparts (stories, sage advice on domestic chores and capturing Mr. Right) but with distinctly Canadian content. Its byline, “Canada’s Greatest Magazine,” was no idle boast: with an English-language circulation of 100,000, Everywoman’s World could, by 1917, claim the largest circulation of any Canadian magazine (Johnston, “Women’s Writes”). Its popularity was a testament not only to the power of the middle-class domestic market in Canada at the time but also to the savvy decisions of its editorial board. Commissioning a memoir from Montgomery was one such example — not only would the memoir guarantee a high circulation for the six months it was serialized (and thus premium prices for advertising space) but Montgomery also represented the kind of feminine middle-class genteel domesticity the magazine sought to cultivate. The benefits of this arrangement would not have been lost on Montgomery: the magazine’s branding affirmed both the nature and value of her public image and would give her access to the largest Canadian audience possible through a Canadian publication.

20 The domestic world of Everywoman’s World is very much in keeping with the world of Montgomery’s fiction and her public image — one is not surprised to discover her memoir in these pages, only surprised to find that its content seems so much odds with the magazine’s domestic mandate. As a narrative of a woman’s career, “The Alpine Path” fits into the magazine’s growing interest in public women and their work — an appropriate development given both suffrage and women’s war work — but an interest consistently qualified by an attention to a woman’s primary responsibilities in the domestic sphere. In the October 1917 issue, for example, Nellie McClung is nominated as Alberta’s “Leading Woman,” yet although her active public life is foregrounded, she and the editors are careful to confirm that her children and husband receive every possible attention (M.M.M. 10). Thus, while the magazine embraced and promoted women’s work in public and political spheres, it was still nevertheless tied to a domestic mandate, in part because of the conservative traditions of its audience but also because it was designed to be a vehicle for selling domestic goods to the middle-class market.11

21 To this end, it appears that the editors expended considerable energy integrating Montgomery’s narrative of her career into the magazine and its mandate. In the June issue, in which Montgomery’s memoir first begins, there is a letter from a reader claiming to want more information on a specific woman’s career (not Montgomery) “and articles of that kind” (Dawe 54). Installments of “The Alpine Path” are promoted monthly, and the July issue also features one of Montgomery’s short stories, “The Schoolmaster’s Bride.” This story, which closely resembles an episode in Anne’s House of Dreams (also published in 1917), invites readers to draw parallels between these two fictional narratives of life in Prince Edward Island as well as the content of the July installment.12

22 More importantly, the appropriateness of women’s writing careers is everywhere articulated in Everywoman’s World, from classified ads that seek writers to a monthly phrenology column that, in the August issue, addresses the question “Will My Daughter Be An Author?” In this particular piece, the author argues that good writing is borne of hard work, dedication, and study and offers phrenological readings of various authors’ visages including Montgomery’s: “L.M. Montgomery — a face of balance and refinement. The smooth high forehead shows love of stories and sympathetic perception, the height and squareness above the temples and the arched eyebrows suggest poetic feeling and artistic taste, while the full eyes show facility of expression” (Farmer 8). This characterization of her face so amused Montgomery that she clipped the column into her journals (SJLMM 1: 344); nevertheless, for readers, this glowing endorsement of her profession and her suitability for the profession, and the flattering photograph that accompanies it, clearly buttress the claim that Montgomery is, indeed, a feminine, genteel woman.13 In addition to this specific attention to Montgomery, the article offers a philosophy on the labour of the writing profession that, not coincidentally, affirms Montgomery’s own sentiments in that month’s installment of “The Alpine Path”: echoing her narratives of the hard work and sacrifice entailed in her “apprenticeship,” the column declares, with various illustrative anecdotes, that great writing is borne of “facility and skill that [. . .] come only with labour, time, and patience” (Farmer 8).

23 There are many other correlations between the content of Montgomery’s memoir and the magazine’s editorial copy, and while some of these correlations are explicit editorial interventions supporting the text, others are so surprising and even ridiculous as to suggest accident rather than intent. Near the end of her installment in the July issue, for example, Montgomery narrates the time in her childhood when the schoolmaster lived with them and she expended all of her “nervous energy” playing outdoors (July 1917: 35). Facing this narrative is an advertisement for Dr. Chase’s Nerve Food, which targets “Schoolgirl’s Nerves” for when girls spend too much time studying and not enough time out of doors. Read together with the advertisement, Montgomery’s text appears to promote this product: if one cannot enjoy an active childhood, the juxtaposition implies, one can at least mitigate the harmful effects of studying too much. While the placement of this advertisement could be a coincidence (Dr. Chase products are routinely advertised in this section of the magazine), it is nonetheless significant that this specific nervous disorder is advertised here and not in the subsequent issue that focuses on women’s education. There, such an ad would do harm not only to Montgomery’s narrative of pursuing higher education but also to the several articles and editorials that support Montgomery’s installment by promoting women’s college education (albeit as a means by which women might better function in their inevitable roles as wives and mothers).

Display large image of Figure 1

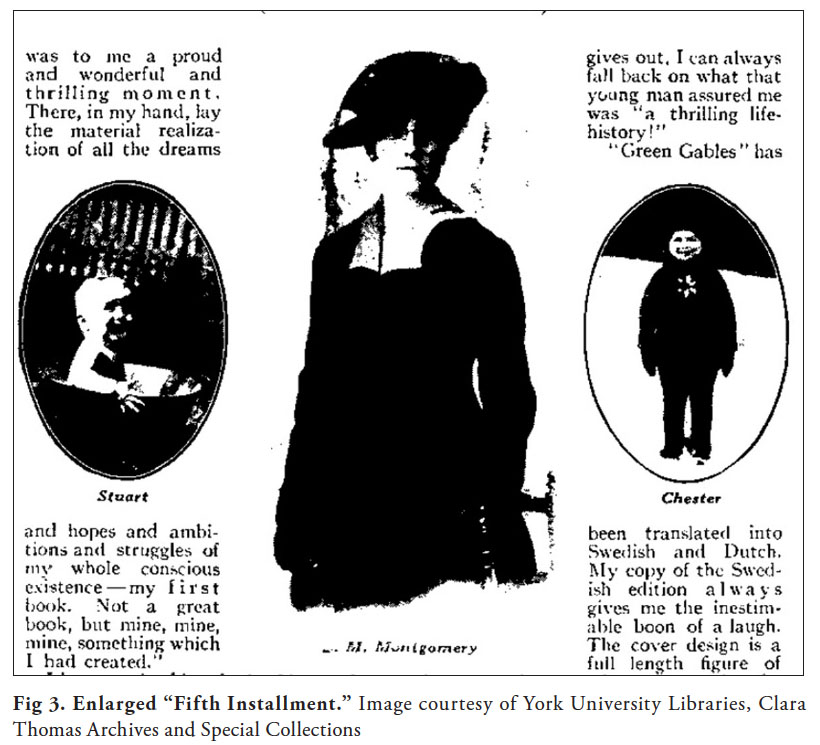

Display large image of Figure 124 The editors, it is clear, worked hard to integrate Montgomery’s text into the magazine, but it is equally important to recognize that Montgomery was also an active participant in the production of an extra-textual domestic frame. Each installment of “The Alpine Path” was accompanied by photographs from Montgomery’s personal collection and first-person commentary. The majority of these photographs show Montgomery at different ages or Prince Edward Island locations mentioned in the memoir or her novels, and in several installments, there are also images of domestic spaces, particularly homes. By the fifth installment (Oct. 1917), however, there is a marked turn in the kind of photographs that accompany the text — instead of images complementing the narratives, the photographs and their captions depart from the narrated content and offer a domestic life hitherto unrepresented in the text of “The Alpine Path.” On the first page of this installment, we are not only offered an image of her Uncle’s home, Park Corner, with a caption telling us that she was married here, but there are also two photographs of her children, Chester and Stuart, who are conspicuously absent from the content of her memoir. These photographs create a gap between the text and the extra-textual frame, which the audience must bridge in order to make these images make sense. Readers are encouraged to draw upon either their previous exposure to Montgomery’s public identity as a wife and mother or, if they are less familiar with Montgomery’s life story, the more general cultural climate that would interpret these images of a woman and two children as a conventional relationship between mother and children.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 325 Editorial interventions also prompt readers to make this connection and recast Montgomery’s career ambition as a form of maternal drive. Her pride upon receiving her first copy of Anne of Green Gables — “the material realization of all the dreams and hopes and ambitions and struggles [. . .] mine, mine, mine, something which I had created” (Oct. 1917: 8) — is used to frame an image of a different kind of labour altogether, her child, Stuart.14 Moreover, an editor’s note at the bottom of the page makes Montgomery’s relationship to this child explicit:

While “outing” Ewan Macdonald as the unnamed pastor of the Ontario church who necessitated Montgomery’s relocation, this note also ensures that the audience reads the images of the children in the context of this marriage. Just as the journalists had done previously, the editor’s note steps in to narrate, describe, and affirm what Montgomery has provided in context but neglected to narrate in content. Yet although the note clarifies and explains, it also misleads: “Mrs. Ewan Macdonald” did not write this “story of her own life”; she wrote the story of “Lucy Maude [sic] Montgomery of Prince Edward Island.” And though the story of “Mrs. Ewan Macdonald” remains untold, her spectre seems to haunt the text: it is through her and her contribution to Montgomery’s brand that readers are able to fill the text’s silences and elisions with conventional gender roles; bridge the gap between narrative content and the contexts of the text’s publication; and turn “The Alpine Path” into an instrument rather than a liability in the production and protection of Montgomery’s brand.

26 Almost a hundred years later, the contemporary reader’s experience of “The Alpine Path”is decidedly different: not only do we experience the text in a different cultural climate and in editions that lack the critical contextual frameworks that shaped how the text was first understood, but we also, often, read Montgomery through the lens of her journals and the identity crafted there. As a result, we may not always appreciate Montgomery’s tactics for producing a particular public image and the role “The Alpine Path” played in that project. It is, thus, a useful and rewarding exercise to read the relevant issues of Everywoman’s World, just recently made available through Early Canadiana Online, in conjunction with media documents assembled by Benjamin Lefebvre and Alexandra Heilbron. But perhaps it is also time for a new critical edition of the text — one capable of recuperating not only Montgomery’s public identity and the various media projects that supported this identity, but also the contexts of the original publication, such as Montgomery’s journal musings, the cultural and political conditions of being a famous woman in the early twentieth century, and the very specific conditions of the memoir’s appearance in Everywoman’s World. Such an edition would have, no doubt, taken Montgomery by surprise — she was certainly amazed to find, in 1936, that someone had taken the trouble to collect and compile all six installments of “The Alpine Path” into their scrapbook (SJLMM 5: 109). Yet “The Alpine Path” was Montgomery’s longest sustained intervention into the circulation of her public subjectivity, and if we are to properly understand how the text represents her domesticity or how she managed other aspects of her brand and public image, then it must be reconsidered in light of these original contexts.

I am much indebted to Benjamin Lefebvre, director of the L.M. Montgomery Research Group, and Peter Duerr, assistant librarian at York University, for their assistance in locating and working with printed issues of Everywoman’s World magazine held by York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections. I would also like to express my thanks to Benjamin Lefebvre and Lorraine York, McMaster University, for their thoughtful feedback on earlier drafts of this work.