Articles

Extraction, Memorialization, and Public Space in Leo McKay’s Albion Mines

In Anne of Tim Hortons (2011), Herb Wyile argues that Leo McKay’s novel Twenty-Six (2003) situates the 1992 Westray coal mining disaster in a broad set of economic and social conditions affecting Atlantic Canada at the end of the twentieth century. This essay considers McKay’s novel in the context of a wider debate over public space in northern Nova Scotia’s Pictou County through post-industrial critiques from Tim Edensor, Rebecca Scott, and Stephen High and David Lewis. While the state’s memorial infrastructure privileges straightforward narratives about the bravery and sacrifice of the miners who were killed in Westray and other disasters, and presents a smooth transition between the dangerous and violent industrial era and the clean and efficient post-industrial era, Twenty-Six employs a nonlinear timeline and images of abandoned space to contest this progressive image of the region.

1 Leo McKay’s collection of short stories, Like This (1995), and his novel, Twenty-Six (2003), take place in a thinly veiled version of his hometown, Stellarton, a small community in northern Nova Scotia’s industrial belt. Stellarton and its surrounding area were home to several of Atlantic Canada’s majorcoal mines during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The key geographical space of McKay’s fictional world is Foord St., which runs through the middle of town and is named after the most significant and volatile of Pictou County’s coal seams. The Foord seam was the catalyst for many of the region’s famous mining tragedies, including an 1880 explosion that killed fortyfour men and, more recently, the 1992 Westray disaster, the inspiration for Twenty-Six.McKay’s novel intersects and comes into tension with strategies employed by the state in memorializing this moment in Canada’s history. The public space of McKay’s version of Stellarton, its parks, streets, memorials, and neighbourhoods, displays the scars of the resource economy at the same time as it communicates the importance of coal mining to the cultural heritage of the region.1 While the state’s memorial infrastructure privileges straightforward narratives about the bravery and sacrifice of the miners who were killed in Westray and other incidents, Twenty-Six employs a nonlinear timeline and images of abandoned space in constructing an open-ended account of the disaster and its aftermath. McKay’s novel interrogates the place of the Westray disaster in Canada’s national imaginary, contesting an ever-present story of progress that centres on a smooth transition between the dangerous and violent industrial era and the clean and efficient post-industrial era.

2 In Anne of Tim Hortons: Globalization and the Reshaping of AtlanticCanadian Literature (2011), Herb Wyile argues that Twenty-Six situates the Westray 2 disaster in a broad set of economic and social conditions impacting Atlantic Canada at the end of the twentieth century. Arvel and Ziv Burrows, two brothers who work at the mine (Arvel is killed in the explosion, while Ziv quits Eastyard after one shift), find it impossible to hold down consistent work in late-1980s Albion Mines. Ziv works part-time at Zellers, where he receives no benefits, and Arvel spends his time “jobbing around,” struggling to parlay his electrician’s training into steady work. Wyile maintains that Twenty-Six connects the explosion to the socio-economic context of the 1980s, a recessionary climate during which “safety concerns were egregiously eclipsed by political and economic considerations” (66-67). For Wyile, TwentySix dramatizes a world in which mine officials and the state ignored blatant safety issues and cajoled workers into doing their jobs even as managers turned off methanometers and ignored pleas to follow even basic precautions, such as laying down stone dust. Wyile also situates Arvel’s death in a generational shift taking place within the Burrows family: as the press and his managers tell Arvel that he is lucky to have a job in such a dire economic climate, his father, Ennis, a successful union organizer and labour activist, berates him about taking pride in his work and pressures both of his sons to find honest employment at Eastyard. Wyile notes that the novel locates Ziv’s and Arvel’s struggles in the instability of a globalized economy that drives down wages, creates groups of underemployed and desperate people looking for work, and strips away the social safety net.

3 This essay considers the novel in the context of a wider debate over public space in Pictou County. On the one hand, this public space delivers a strikingly similar message to inhabitants regarding the region’s economic circumstances: it tells people about the county’s proud history of coal mining, that the mines contributed to the project of constructing Canada, and, perhaps most importantly, that the area remains a resource colony with a store of coal that needs to be taken out of the ground by any means necessary. On the other, the fractured temporal structure of McKay’s novel and his emphasis on abandoned industrial sites and buildings and their role in memorializing the disaster complicates an abstract reading of the space of Pictou County that sees the region as a series of resources just waiting to be extracted.

Stellarton and the Politics of Memorialization

4 McKay’s fiction aims to understand the particular political, economic, and social context of post-industrial northern Nova Scotia, and Foord St. stands as a microcosm for the shift from the industrial era to the age of call centres, retail jobs, and “flexible” work. Most of the streets that intersect with Foord are named after mine shafts or mining companies; it is home to two miners’ memorials as well as the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry; and on North Foord St., just blocks away from the company houses of the Red Row (which feature prominently in McKay’s work), the national headquarters and distribution centre of one of the region’s largest retail companies, Sobeys, loom over the rest of the county.

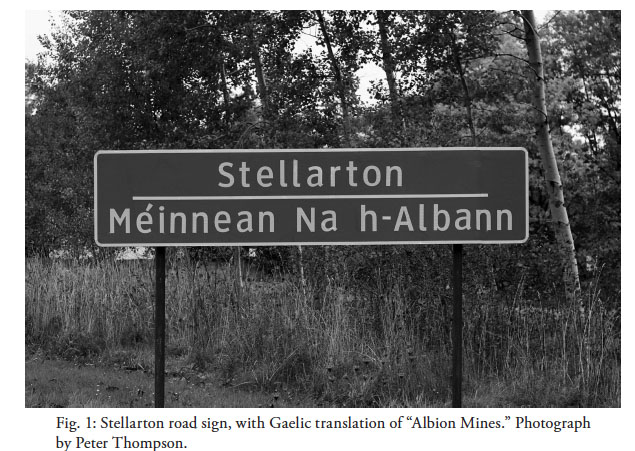

5 McKay calls Stellarton by the name given to the area by the General Mining Association in 1827, Albion Mines.3 While most of Stellarton’s streets, parks, and neighbourhoods are named after mine managers, seams, and pits, the only place other than McKay’s work where this name currently appears is on the green road signs at the three major entrances to town. In 2006, the Nova Scotia Department of Transportation and Infrastructure Renewal established a policy allowing Gaelic place names to appear on road signs for regions in the province where inhabitants historically spoke Gaelic. The department also created a website for visitors who might be less comfortable with pronunciation to find out more about these names and to have them sounded out phonetically.4 Instead of providing a Gaelic translation of Stellarton, the department translated the original name of the town, Albion Mines, to Méinnean Na h-Albann, a subtle but significant nod to the area’s colonial past, its status as a resource base for the rest of the country, and to the state’s push to attract visitors to the area by highlighting its real or imagined Scottish heritage.5 While it may seem like a relatively small detail, this sign, like McKay’s work, disrupts a narrative of progress that the Canadian state looks to construct, one that accentuates Canada’s maturation from colony to nation, and glosses over inconvenient and unpleasant events like the process of settling the country and industrial accidents.

6 The Westray disaster, which resulted in the death of twenty-six miners, is a key event in this narrative. Spurred on by political manoeuvring designed to consolidate Brian Mulroney’s and Donald Cameron’s power in the late 1980s, Westray brought international attention to Canada and to Pictou County and led to a wholesale restructuring of the industrial economy in the region (which was already in decline).6 By calling his fictional community Albion Mines, McKay suggests that less has changed in the time since the founding of the coalfield in this area than we might like to admit. The novel reminds readers that the narrative of belonging and sacrifice that nationalism constructs necessarily depends on the ability to forget certain things (Renan 11).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 17 The name “Albion Mines” appearing on these prominent signs and in McKay’s fiction also calls attention to connections between what John Urry calls “the tourist gaze” and what we might call “the extractive gaze,” a term that describes industrial society’s preference to view the environment as something that can be divided up, surveyed, and mined for resources.7 Tourist brochures and advertisements in places such as Atlantic Canada bolster the extractive gaze by glossing over the environmental impact of the resource industry, by directing attention away from the history of labour disputes, and by refashioning accidents and disasters as heroic moments.8

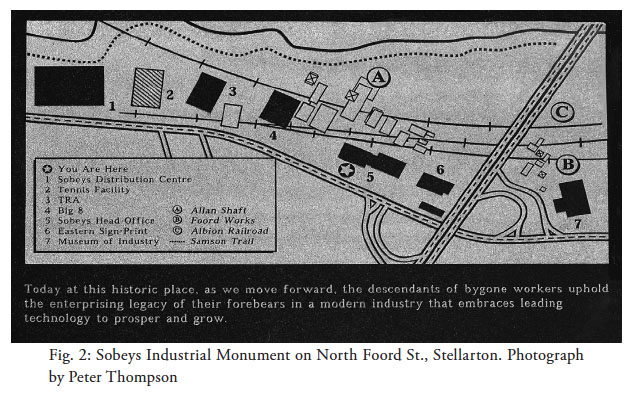

8 McKay’s fiction demonstrates that this impulse has a significant impact on the way in which contemporary Nova Scotia commemorates the coal mining industry. The logic of the post-industrial economy dictates that memory and history should be turned into material objects or spectacles, partially because of the crisis of identity that accompanies this kind of restructuring and partially because new economic development often relies on communities’ ability to sell themselves and their culture (Edensor 126; McKay, Quest of the Folk; Whitson 76). This is particularly true in Nova Scotia, a place where the tourist gaze has flattened out the edges of historical narratives and turned the past into a saleable commodity. Robin Bates and Ian McKay argue that Nova Scotia is home to a series of a-critical sites such as heritage districts, Victorian-style bed-and-breakfasts, and breweries where history is decontextualized and presented as entertainment (371). Since history and commemoration have become such integral elements of the tourist economy, the state and corporate interests delineate specific sites where memorialization can take place and favour commemorative experiences that are straightforward and ideologically sound.

9 As regional literary critics and historians have pointed out, the commodification of culture and history in Atlantic Canada invites particular interpretations of the past in which, for example, tourism is read as hospitality, economic disparity is read as quaintness and innocence, out-migration is read as evidence of an adventurous spirit, patriarchal authority is read as a commitment to the traditional family, and industrial accidents are read as instances of bravery.9 In addition to heritage districts and interpretive centres that position Atlantic Canadians as cheerful (if backwards) contributors to the “national community,” spaces such as the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry construct the history of resource extraction and manufacturing in the region as a story of sacrificein which communities such as Stellarton and Glace Bay can take pride in having had a role in literally constructing the nation, even if they have fallen on hard times.

10 Herb Wyile argues that coal mining fits uneasily into Atlantic Canada’s folk paradigm (55). While fishing and farming lend themselves to romantic ideas about connecting with nature, living off the grid, and working hard to earn a meagre living for one’s family, the coal industry is much more difficult to idealize. The history of coal mining in Atlantic Canada is full of disasters and explosions, acrimonious fights between labour and management, and is capped off by a crippling and ongoing process of deindustrialization, in which entire communities have been devastated by pit closures and the retreat of capital. As Wyile demonstrates, however, contemporary Atlantic Canada is defined in large part by the region’s relationship with resource extraction: the offshore oil and gas industry seems poised to offer a way out of the region’s depressed economic conditions and a pool of transient labour from the region drives development in Alberta’s oil sands.

11 In her work on the cultural and environmental impacts of mountaintop removal mining in West Virginia, Rebecca Scott argues that the public space and cultural history of coal mining areas play an important pedagogical role within these communities. Children learn that an arm of the imperial government such as the General Mining Association founded their hometown and that they owe their community’s housing and infrastructure to these industrial concerns. Scott calls coal a “mythic commodity” (6) — much like fish and oil — that is fetishized through songs, monuments, jewellery, and stories passed down through generations long after the industry’s heyday. Scott suggests that industrial museums locate coal mining in a narrative of national expansion and technological development. She argues that exhibits in these institutions often “selectively forget” elements of the history of coal mining and present the industry in a very straightforward, if not romantic, way: the coal companies arrived, they extracted what they could from the landscape, some people died heroically, and finally the age of coal ended, leaving behind a clean and safe post-industrial economy. This nostalgic reading of the history of coal mining positions spaces such as Pictou County as resource colonies for the rest of the country and works to “refigure an industrial wasteland into a postindustrial space of entertainment, nostalgia, and consumption” (Scott 144; see also Bommes and Wright, Zukin, among others).

12 Much of the memorial infrastructure on Foord St. employs this kind of nostalgic reading of the history of coal mining in the area. This is clearly the message delivered by Sobeys, which built its own miners’ monument when it unveiled its new national office in Stellarton in 2000. The Sobeys Industrial Monument is designed to insert the company and its various enterprises into the industrial heritage of the region. The map of Pictou County on the memorial places Sobeys’ distribution centre, the Big-8 factory, and its head office next to shuttered mine sites, such as the Allan Shaft, and composes a historical timeline in which the closure of mines coincided with the rise of Sobeys as the town’s major employer. The inscription on this monument reads: “Today at this historic place, as we move forward, the descendants of bygone workers uphold the enterprising legacy of their forebears in a modern industry that embraces leading technology to prosper and grow.” This monument, along with the state’s tourism and memorialization complex, constructs a historical narrative in which the service industry’s call centres, interpretive displays, hotels, cultural performances, and grocery stores seamlessly replaced resource extraction.10

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 213 The Nova Scotia Museum of Industry memorializes the Westray disaster and other mine collapses and fires in much the same way, offering interpretive displays called “Coal and Grit,” “Blood and Valour,” and “The Mining Life.” Built during the same era as Westray, the museum was designed to document and memorialize the legacy of industrial development in Nova Scotia, including the steel-working industry, the railway, and especially coal mining.11 The Museum of Industry supplanted a small, community-run mining museum in Stellarton, and, in a further irony, hosted the public inquiry that looked into the safety conditions at Westray. However, Twenty-Six resists the narrative of progress outlined on the Sobeys memorial and in the Museum of Industry — the idea that we have learned from the past and that working conditions have improved — and calls our nostalgic response to the fall of the industrial economy into question.

Public Space in Twenty-Six

14 Stellarton has a complex relationship with its industrial past. While the state and corporate interests fashion a commemorative structure that emphasizes closure and progress, Twenty-Six resists this reading of the coal mining industry, complicating the process of memorialization. To do so, McKay employs a distorted temporal structure throughout Twenty-Six. He pushes the date of the Eastyard explosion back to 1988 and constructs a nonlinear narrative in which the story jumps from year to year and events take place repeatedly and from different perspectives. One of the novel’s pivotal scenes, Arvel leaving his parents’ house for the mine, which he ominously calls his “grave,” is retold several times. The repetition of these moments makes the temporal layout of the novel seem arbitrary and punctuates one of the novel’s central messages: although the poor working conditions, disregard for safety, and ultimately the disaster itself seem as though they are events, in Ziv’s words, that might have taken place in, say, the 1880s, Westray took place during the late twentieth century under the supervision of the Nova Scotia government.

15 One of the novel’s key sequences is when the main characters of Twenty-Six find out about the explosion. This unfolds several times, with Ziv experiencing a bump while he is sleeping over at his friend’s house; Meta, Ziv’s sometime girlfriend, hearing about the news in Japan; Dunya and Ennis, the Burrows brothers’ parents, feeling the explosion in bed; and Jackie, Arvel’s recently estranged wife, receiving an anonymous call from Eastyard’s human resources department — the mine kept such poor records that the company was unaware of who was working at the time of the explosion and had to call around to find out which miners were potentially on the job site. The narrator juxtaposes Meta’s discovery of the disaster through news reports in Tokyo with the residents of Albion Mines learning that something terrible has happened by waking up to the ringing of an air raid siren in the middle of town. Hearing this siren is especially disturbing for residents because the disaster marks the first time that it has been used in an emergency situation. During the previous fifty years, the siren had only been heard when the town was conducting routine maintenance tests or offering curfew reminders to local children.

16 Just before his final shift, Arvel dreams about the Red Row of the early twentieth century, seeing a series of houses with coal sheds and no indoor plumbing and walking his regular route to the pit with his grandfather (who, in the dream, is the same age as he is). McKay renders time arbitrary and even meaningless by playing around with the sequence of events in his narrative and by inserting Arvel into another moment of the history of coal mining in the region. By embedding the present with so many reminders of past coal extraction and disaster, Arvel is simultaneously an observer and participant in this dream; he walks with his grandfather at the same time as he narrates the dream from a distance. When he sees the hustle and bustle of the town he is dreaming about, the level of activity surprises him, even though, at the same time, he is familiar with these images: “these buildings before him, this smokestack, the wheels that turn the big lift: these have been written on his mind by something stronger than memory” (67-68). At first glance, it is easy to read Arvel’s statement as a kind of gesture to a sense of cultural memory or inheritance in which, to use a phrase that one reads often in literature about mining, coal is in his blood. However, Arvel’s intimate knowledge of the town’s coal mining past comes instead from being reminded of it over and over by Albion Mines’ memorial infrastructure.

17 After the explosion, Ziv walks past the miner’s memorial on Foord St., where he “pauses to look up at the statue on top of the miner’s monument, the old-time miner with his safety lamp. There is no space left for names on the pedestal. Eastyard will require a whole monument unto itself” (306). Elsewhere, the narrator points out that the miner’s monument had “more names on it than both sides of the war monument put together” (17), a piece of local trivia that McKay has talked about in interviews (Methot 16). The manager of the old community-run miner’s museum, George Hannah, becomes something of a folk hero in the aftermath of the disaster when footage emerges of him telling a reporter on the eve of Eastyard’s first shift that the Foord seam is too dangerous to mine. He says, “‘You’d might as well build the memorial to the dead right now. . . . Just leave plenty of room on it to carve the names in later” (197). McKay locates this event in a temporal space in which the disaster was at once pre-ordained and also caused by willing negligence on the part of managers and politicians, who mixed hubris, a lack of regard for human life, and desperation in creating the conditions for it.

18 McKay enhances the distorted temporal structure of Twenty-Six through a preoccupation with abandoned space, including discarded factories, sinkholes caused by subsidence, and derelict industrial sites. McKay presents a deindustrialized landscape in which development has stalled, finances have dried up, and companies and workers have abandoned manufacturing sites, which become symbolic of transition and decline, instead of promise and development. In Corporate Wasteland: The Landscape and Memory of Deindustrialization (2007), Steven High and David Lewis argue that these sites inspire two responses. The first is the widespread belief in North America that stripping down the manufacturing base and shuttering factories is a natural part of capitalist development and that people who live in areas affected by these closures have failed to adapt adequately to changing circumstances. The other, perhaps more diffuse, response is nostalgic: industrial ruins represent a moment in time when work knit communities together, when the resource economy sustained the nuclear family, and when masculine culture thrived.12

19 Critics such as D.M.R. Bentley, Brooke Pratt, and Justin Edwards have suggested that Canadian authors have long been attracted to abandoned space. They argue that ruins, obsolete buildings, overgrown railway tracks, and empty outports at once connect us with the past and create a sense of uncertainty or dread about the future. In the specific case of Canada, abandoned spaces evoke what Cynthia Sugars and other English-Canadian theorists have identified as a set of cultural anxieties about belonging and the dominant society’s tenuous relationship with the land. Although critical attention in Canada has focused heavily on ghost towns and crumbling houses, abandoned industrial sites are increasingly prevalent and play a particularly key role in contemporary Atlantic Canadian literature.13 These spaces disrupt our understanding of progress and development and call attention to the failure of modern capitalism to provide universal security, even in a country with an advanced economy such as Canada. While ruinsclaimed and managed by the heritage industry might connect us to a romantic narrative about the past and represent physical evidence of the nation and its imagined community, abandoned industrial sites call attention to breaks and slippages in our relationship with the past and with development.

20 In the national imaginary, regions such as Pictou County are positioned as “sacrifice zones” (Scott 161) that suffer environmental and health-related consequences of resource extraction and eventually experience such fallouts as economic depression, increased levels of drug addiction, and outmigration in the post-industrial era. Scott argues that while the “logic of extraction” covers up evidence of problematic historical events such as labour violence, industrial accidents, and the boom-and-bust cycle of the resource economy, remnants of mining in the form of subsidence, memorials, and abandoned buildings still mark the landscape of these areas. She argues that these traces serve two functions. On the one hand, the decaying factories and abandoned mines communicate to inhabitants of coal mining regions that they are dependent on an industry whose best days are behind it, and thus contribute to economic and cultural circumstances in which employers overlook safety concerns and drive down wages. At the same time, however, the empty buildings and industrial sites of these regions also contest ideas surrounding universal progress and the ability of the heritage industry or mining companies to “reclaim” the land and make it usable through building commemorative plaques, or turning it into parks and other recreational spaces (Goin and Raymond 30).

21 In his 2002 study, Industrial Ruins: Space, Aesthetics, and Materiality, Tim Edensor argues that projects designed to improve abandoned industrial spaces give us the sense that these dangerous industries have purposefully and smoothly been replaced by the cleaner, safer, and more efficient occupations of the post-industrial era. He argues that “modern capitalism proceeds by forgetting the scale of devastation wreaked upon the physical and social world, for obliterating traces of this carnage fosters the myth of endless and seamless progress. However, lost and abandoned objects convey this destruction” (101). Building on Henri Lefebvre’s observation that capitalism relies on a colonization of space and an abstract reading of the physical environment in which all space is either useful or potentially useful, Edensor suggests that abandoned buildings constitute sites that contest this idea (8). He argues that abandoned sites convey the destructive history of resource extraction, resist closure and surveillance, locate objects both in the past and the present, and defy easy explanation and commodification. Industrial ruins represent instability, traces of the past, and material reminders that development takes place unevenly (Nielson 60).

22 Ziv and Arvel grew up in a neighbourhood that struggles with reconciling these issues, the Red Row, “a half-dozen or so blocks of duplexes built by the Acadia Coal Company in the first decades of the century” (5). Ziv says that he is constantly aware of the history of mining in the region: he hears stories about it from his relatives, and many of his neighbours are retired coal miners. For Ziv, the deep connection between his neighbourhood and the mining industry is oppressive: he often compares the feeling of being “completely submersed . . . in that murky history” (5) with the feeling of the weight of the earth bearing down on him while working underground (16-17). As David Creelman argues, the characters who inhabit the fictional world of McKay’s short story collection, Like This, are “disconnected from their cultural heritage and are immersed in the immediate, insurmountable problems of the present” (212). This changes in Twenty-Six, however, as the characters in this novel struggle against the prevalence of reminders of the mining industry and a cultural heritage to which they have lost access. Ziv and Arvel experience alienation precisely because they are constantly being made aware of this lost way of life.

23 Ziv and Arvel’s preferred place to play as children was George Hannah’s mining museum, where they signed false and humorous names on the guestbook and joked around about the strange objects housed there. Arvel recalls being struck by pictures of trams, factories, and people milling about in his now essentially empty hometown and says that the strange tools housed in the museum “were like the relics of a lost civilization” (84). Even as he looks at the lists of collapses and explosions and thinks about the men who lost their lives, Arvel laments the loss of this way of life and the industry that supported it, noting that his will be the “first North American generation to fare worse than their parents” (83).

24 Ennis and Dunya’s violent reaction to the explosion also brings the importance of these material reminders of the mining industry into focus. Ennis goes on a rampage and destroys almost all of their furniture and possessions, causing Dunya to hit him with a heavy pot, which puts him in a coma for the duration of the search. Dunya proceeds to strip the house of everything they own, leaving behind only a wooden dresser from Ziv’s room that they are unable to fit out the door. The dresser, which had been built in the room from “old powder boxes from the pit” (237) and is inscribed with the word “explosive” on its side, serves as another reminder to the Burrows family of the impact of coal mining on the region and their family. While Ziv and Arvel feel economic and familial pressure to find jobs at Eastyard, these objects as well as the landscape of Albion Mines communicate the importance of the mining industry to the culture of the region.

25 One of the most distinctive features of McKay’s Red Row is the “big cut-stone remains of the Cornish Pumphouse, a hundred-year-old relic of the mining heydays” (256), which Ziv walks past every day on his way home. The pumphouse, as the narrator observes, makes him think about the conditions under which his neighbourhood was built and its place in the post-industrial landscape of Atlantic Canada:

One of the most dramatic effects of deindustrialization is the retreat of capital from regions in which a significant number of people still reside. For Ziv, this essentially means that he and the other inhabitants of his neighbourhood live in discarded company houses and are surrounded by a series of objects to which they are both intimately attached and alienated. The physical geography of Albion Mines serves as a constant reminder to Ziv and the rest of the inhabitants of the community of the tumultuous history of resource extraction in the area. Ziv’s cultural alienation certainly stems from growing up in a world in which he is unable to find steady work and is constantly judged against his father’s success in the world of manufacturing; however, it also comes out of the experience of living in the former company housing of an industry that has all but died out. Ziv constructs himself as an outsider to the space of Albion Mines, in spite of the fact that he grew up and lived in the town his entire life.

26 McKay juxtaposes Ziv’s sense of alienation with the sections of the novel that take place in Japan. Meta writes Ziv letters from Tokyo, where she has travelled to take a job teaching English. Meta struggles in much the same way as Ziv to navigate her neighbourhood, which is at once familiar and completely alien to her. Just as Meta floats on the surface of a society that she does not completely understand, Ziv and the rest of the inhabitants of the Red Row seem unable to come to terms with their relationship with the region’s industrial history and the overwhelming sense that they no longer belong in this space.

27 Albion Mines’ history as a resource base first for the British Empire and then for Canada has a significant impact on the town’s physical geography. When Ziv leaves his hometown for university, he is struck by the steady growth he encounters in the town to which he moves, contrasting it with the uneven landscape he left behind:

The landscape and public space of Pictou County display material indications of the history of the region’s industrial era. As industry and capital gradually moved out of the area, the landscape was left with a series of scars and traces that have partially grown over, but are still very much present.

28 When the explosion at Eastyard takes place, Ziv initially believes that the bathroom he was in at the time shook as a result of routine subsidence, “a fall of earth from the cave-in of an abandoned mine shaft [which] sometimes swallowed up a house. . . . Several homes had given way in Westville, and there was an area near Bridge Avenue that had sunk by several metres when he was a kid” (182). Elsewhere, Ennis follows a moose into a swampy basin, a hole created by the after-effects of a century of mining in the area; he notes that the county is “pockmarked by holes like these, places where long-abandoned mine workings, far below the surface, have given way, collapsed” (346). Although most of the mines in the area have long been abandoned, the inhabitants of Albion Mines continue to live with the fallouts of the industry: mining shapes the landscape and continues to have a deep impact on the culture of the area.

29 The impact of these material and cultural reminders of the mining industry becomes clear in the weeks following the Eastyard disaster. The chaos of the explosion and the efforts by draegermen to find the bodies of the missing quickly shifts to hearings about who is responsible for the disaster and debates over how to properly memorialize the dead. Ziv and Arvel recall legendary stories about the violence of coal mining in Albion Mines: they cite off the top of their heads the approximate number of people killed mining coal in the region; they remember that their relatives talked about coal miners using the same hushed tones of respect and fear that they reserved for soldiers in the war (252); and the narrator says that Ziv had “grown up with the myth and lore of the Pictou County coalfield, and that lore was about nothing if it was not about injury, perilous danger, and violent death” (265).

30 Part of the way that Twenty-Six resists these mythic narratives is by dramatizing the debate over what to do with the most distinctive and imposing element of Pictou County’s post-industrial landscape: the blue and gray silos of Eastyard, which are visible from virtually anywhere in the county. After being broadcast around the world in the days after the explosion — for example, Meta does a double-take when she sees them on an international news program in Japan — the silos became emblematic of the disaster: “Constructed of ugly concrete and steel, there was nothing remarkable about the look of them at all. This was the same sort of unsightly industrial complex that scarred the landscape in other parts of the county, except that this was new” (266). The silos quickly become a constantly visible focal point in the debate over how to acknowledge the disaster.

31 Several of the families push to have the silos protected and declared permanent memorials to the dead; however, there is a strong desire on the part of the rest of the public and the state to destroy them. Ziv’s friend, Jeff Willis, leads the former camp, arguing that in housing the story of the disaster in museums operated by the state, the government is “trying to sweep the history of this event under the rug. And the death of my brother along with it” (375). He goes on to say that “my brother is buried at Eastyard Coal. Until his body is recovered, those silos are his gravestones” (375). The narrator says that the silos are visible from the TransCanada highway to people passing through the province, and that they are “unignorable, one of the most visible landmarks in the province. They are a symbol of all that’s wrong with Nova Scotia’s political and economic life” (375). Ziv decides to join Willis in this fight, stating that “the two pale columns of featureless concrete could not look more like a memorial if they were originally designed that way” (382) and noting that the families of Eastyard are lucky to have such a powerful reminder of what happened embedded in the landscape. The families on this side of the debate argue, like Edensor, that the abandoned silos represent a powerful rebuke to the straightforward narrative of the disaster produced by the state’s memorial complex.

32 Of course, the postscript to the novel is that the real silos were destroyed in 1998 in a very public and ritualized display and the story of Westray was transported across the river to the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry.14 High and Lewis argue that the destruction of factories, grain elevators, and mine shafts represent “secular rituals” in which crowds gather, politicians give speeches, and news agencies provide wide coverage of the ceremonial demolishing. For High and Lewis, the demolition of these landmarks announces the end of the industrial era and tells onlookers that the social and economic systems it once sustained are fundamentally changing. This is certainly the case in Pictou County, where the implosion of the Westray towers spelled the end of whatever was left of industrial expansion in the area.15

33 In one of the final scenes of the novel, Ziv stands on Foord St. and looks out toward the East River, where he can see the Red Row, the Museum of Industry, and the silos of Eastyard all at the same time. McKay’s novel forces us to see connections between these three elements of Pictou County’s landscape, insisting that politicians and corporate interests capitalized on the region’s economic conditions and the alwayspresent history of the mining industry to will the mine into existence, and then turned to the commemorative apparatus of the state to make sense of the disaster after the fact.

34 Twenty-Six resists the pastoral and innocent version of Atlantic Canada pushed by the tourism industry and calls attention to the region’s uneasy place in Canada’s federation. While the nostalgic impulse that has annoyed a generation of Atlantic Canadian writers favours straightforward and easy-to-understand accounts of the mining industry, McKay locates Westray in a moment in which a depressed economy, a lack of regard for safety, and traces of coal mining in the public space of Pictou County combined to set the stage for the disaster. For McKay, Westray exists at both the extreme margin and heart of national discourse in Canada; he demonstrates that Pictou County is positioned as a resource colony for the rest of the country and that in the aftermath of the explosion, narratives about progress and technological development provided a way to make this event comprehensible and to mitigate the idea that the state, the rest of the country, and the developers responsible for the mine viewed the workers at Westray (and the inhabitants of the county) as expendable.

35 While readers sometimes pass off Twenty-Six as didactic or heavyhanded in its critical treatment of the Westray disaster and its aftermath, paying attention to the novel’s treatment of public space reveals the nuances of McKay’s presentation of the region’s industrial heritage. McKay’s position on the political and economic conditions that precipitated the explosion seems clear; however, Twenty-Six captures the complexity of northern Nova Scotia’s response to memorializing the disaster and dealing with the fall of the industrial era. McKay’s characters are caught between fondly remembering and renouncing an industry that played an extremely important role in driving economic development and building infrastructure while simultaneously destroying the environment, exploiting workers and their families, and maintaining dirty and unsafe working conditions. The impact of the memory of the mining industry on McKay’s characters is clear: Ziv and Arvel are lost and alienated without it, and Albion Mines is struggling to figure out what comes next.

36 By presenting a fractured temporal structure, calling Stellarton by the name given to it by the General Mining Association (and the Nova Scotia Department of Transportation and Infrastructure Renewal), and examining the politics of commemoration in Albion Mines, TwentySix highlights post-industrial Nova Scotia’s complex and ambivalent relationship with the legacy of the coal mining industry. The state and corporate interests divert attention away from the impact of coal mining by treating the death and injury of workers in events such as Westray as necessary elements of the story of national expansion. In the case of Pictou County and many other parts of Atlantic Canada, the tourism industry and the state consolidate and advance this project by disciplining the gaze of outsiders to look only for picturesque or highly mediated landscapes and by latching on to a reading of the industrial heritage of the province that accentuates bravery, sacrifice, and anti-modern notions of the continuity of work. Leo McKay’s work calls attention to the prominence of remnants of the mining industry and muddies the debate over memorializing the Eastyard/Westray disaster. In doing so, Twenty-Six contests this tendency to view Atlantic Canada through such a nostalgic lens and resists the idea that Westray was a tragic moment in the region’s otherwise smooth progression into an efficient and hospitable post-industrial economy.