Articles

From Serial to Book:

Leacock’s Revisions to Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town

— Stephen Leacock, Moonbeams from the Larger Lunacy

1 When asked for his advice by Stephen Leacock in 1909, editor B.K. Sandwell, a former student of Leacock’s at Upper Canada College, advised against publishing in book form a selection of the comic sketches Leacock had been writing for magazines since his college days. Sandwell was anxious about Leacock’s professional reputation as a serious political economist, which Leacock had become in 1906 with the publication of The Elements of Political Science, the work that would remain, surprisingly, his bestselling book. Ignoring Sandwell’s advice and rejected by Houghton Mifflin, the American publisher of his economics textbook, in 1910 Leacock, at his brother George’s urging, self-published Literary Lapses. In what has become a Canadian publishing legend, the slim green-boarded volume was picked up at a Montreal newsstand by British publisher John Lane to charm some travelling boredom, and subsequently published by his The Bodley Head to the acclaim that launched Leacock’s career as the English-speaking world’s most popular humorist for the period roughly 1910-1925.

2 In the fall of 1911, a perhaps contrite Sandwell arranged a meeting between Leacock and Edward Beck, the managing editor of the Montreal Daily Star. The result of that meeting was, in Sandwell’s words, “the only really large-scale commission that Leacock ever received for a fictional job to be done for a purely Canadian audience” (Sandwell 7). Thus the first notable influence that newspaper serialization had in the history of Leacock’s masterpiece, Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town: the targeting of a Canadian readership for his most coherent, and many have attested his best, volume of humorous fiction (with only 1914’s Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich to rival its claim).

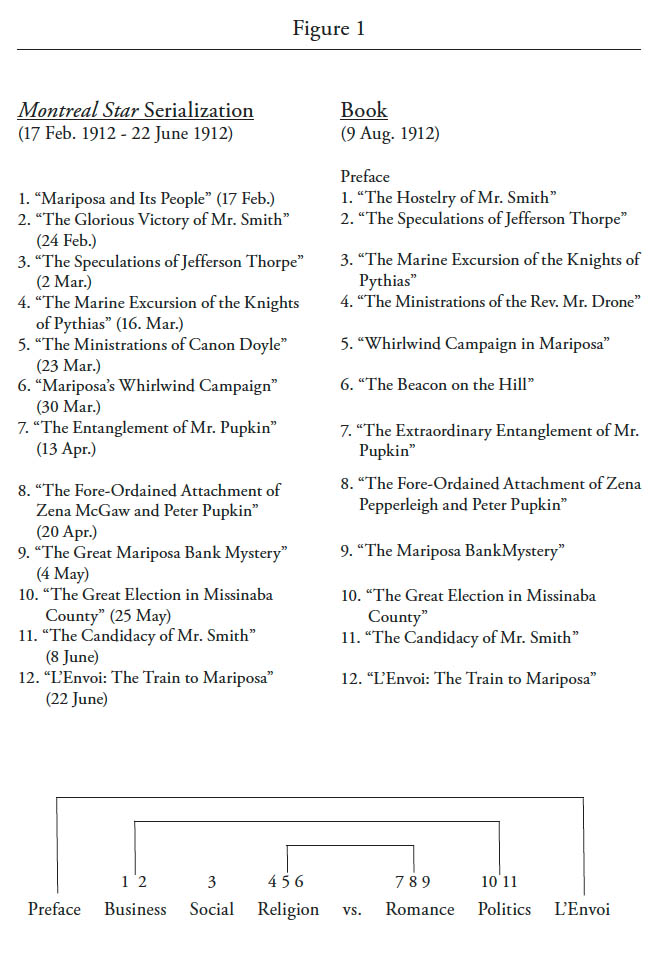

3 The series of twelve sketches that would become the book Sunshine Sketches began running in the Star on Saturdays from 17 February 1912 through 22 June 1912, and was first published in book form by John Lane on 9 August (Spadoni 115), only a month and a half after the final serial installment. Already on 24 February — only a week after the first sketch appeared — Leacock was writing to Lane in England: “I send you under separate cover some stories called Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town. They are appearing in the Montreal Star and two or three small Canadian papers: but I have reserved the books [sic] rights and the serial rights outside of Canada. I hope to do ten or twelve of these and to make a book of about 50,000 words. So if you would care to serialize them in England or in the United States and then publish them in book form I should be delighted. But I should not care to have them serialized in any way that would delay the publication of the book” (Staines 71). When his publisher declined the opportunity to serialize the sketches in England or America, undoubtedly presuming a lack of interest in small-town Canadian life, Leacock returned undaunted to his pressing interest in immediate book publication, again writing Lane on 2 March: “I am posting you more Sunshine Sketches tomorrow. Would you feel inclined to start printing them at once to save time. Of course I’ve only written 25,000 words so far and might get stuck or fall ill. But it would help greatly with Canadian sales to put the book on the market in May right after the newspapers are finished with the stuff” (Staines 72-73). This sense of urgency for book publication, compounded by the slight deception regarding the projected terminal date for serializing “the stuff,” continues through March, with Leacock promising John Lane on the 20 th that “all [of Sunshine Sketches will] be in your hands in another month” (Staines 74). Then suddenly, at the start of April, Leacock’s urgency vanishes: “I’m afraid I sent your reader awfully bad copy: I will now keep the rest of the Sunshine Sketches in hand and send you the whole copy from the start in a revised and corrected form so as to minimize proof reading” (Staines 74). And in the second week of May he writes to Walter Johnson, The Bodley Head’s managing director, “I am sailing for France tomorrow and will post my MSS from there to London. It fills 53,000 words with an autobiographical preface of 1,000 more” (Staines 75). With serialization in the Star having still over a month to run, Leacock had already revised the whole manuscript of Sunshine Sketches, in transit and at Paris. Fast work.

4 Nonetheless, within some three months of having begun the serialization of Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town, Leacock reined in his madly galloping desire to have it published in book form almost simultaneously with serialization in the Montreal Daily Star. Given Leacock’s practice of writing quickly and publishing immediately, and often the same piece repeatedly (see epigraph above), his concern for the labours of Lane’s proofreaders is at least suspect and plausibly dismissible. Most important in the letter quoted above, his reference to having added an “autobiographical preface” is the first indication of the extent of the substantial revisions he was making to the serialized version. 1 In the book, the author’s preface not only adds symmetry, providing an opening authorial frame for the closing “L’Envoi: The Train to Mariposa,” but also a third narrative voice and perspective. Leacock’s persona introduces himself to the world, giving the facts of his life in an ironic voice that is matched only by the Sketches’ narrator on the town of Mariposa. This is a more telling observation than it may first appear, as the tonal similarity in the two distinct voices can help toward answering the much vexed question of Leacock’s true view of Mariposa, and consequently of the town on which Mariposa was based, Orillia, Ontario, and of the country, Canada, which the town in the sunshine was imagined to represent “for a purely Canadian audience.” Which is to say: despite the unrelenting irony and satiric barbs of Sunshine Sketches, Leacock may well have cherished Mariposa as he did his own life; and Leacock, apparently a stranger to self-doubt, thoroughly enjoyed his seventy-four years (Lynch, Leacock on Life xv).

5 Before mid-May 1912, then, Leacock had recognized something worth his more extended attention in what was to become Canada’s first great comic fiction of the twentieth century, the book that Mordecai Richler said was “the first work to establish a Canadian voice” (Richler xiii). The determinedly unsentimental Richler’s appraisal, recorded in what was his last piece of literary journalism (an introduction to a 2000 UK edition of Sunshine Sketches), is truer than most readers — especially Canadian readers — are still willing to recognize, which is a pity. Despite having passed virtually unnoticed, Richler’s assessment could, and should, serve for Canadian literary culture as the equivalent of Ernest Hemingway’s watershed pronouncement that all modern American fiction flows from Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn (Hemingway 19). 2 As such, Sunshine Sketches, here specifically its publication history, deserves much more critical-scholarly attention than it has been given, though in recent years the scholarly work of Carl Spadoni (bibliography) and David Staines (selected letters) has gone some ways toward rectifying the lack.

6 In the remainder of this essay I will describe some of the other changes Leacock made between the serialization of Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town and its publication as the complete work of literary art that has come down to us. The initiatory commission to write for a Canadian readership, Leacock’s seeing the serialized version of Sunshine Sketches unfold in the Montreal Daily Star, his experiencing readers’ responses even while he was busily writing the next instalment — such conditions of serial publication would naturally have contributed significantly to the process of revising for book publication. Although there are a number of books on the history of serial publication (Richard Altick 1957, 1991; Graham Law 2000; R.M. Wiles 1957, 1965; Patricia Okker 2003), the transition from newspaper and magazine serialization to book publication has not received much attention. When it has, as in essays and papers by Kevin Morrison, Robert L. Patten, and Carole Gerson, the purpose — one that I endorse — has been to treat the original serialization as a distinct text with its own life respecting reader-ship and author. As Gerson directs, “we as critics and scholars should approach our subjects with greater circumspection when we know that the contents of books were initially published in other contexts” (9). We should. My purpose here, though, is different: to examine the ways in which the revisions made in the transition from serialization to book publication shed light on Leacock’s intentions with the Sketches in the first half of 1912, which should contribute to a better appreciation of his view of the purpose of humour and, more generally, his comic vision of humanity and the coming metropolitan modernity.

7 Of greatest interest in such a consideration are the structural changes that Leacock made — the additions, combinations, and divisions (no deletions) — but it is worth briefly noting some of the minor revisions. As is well known, Sunshine Sketches’ Mariposa was based on the town of Orillia, a hundred kilometres north of Toronto. From serialization to book, Leacock changed the names of some of the characters who were but thinly veiled actual Orillians. For example, in the Star, the book’s Henry Mullins is called George Popley, who was based on Orillia’s George Rapley; Judge Pepperleigh appears in the Star as Judge McGaw, who was based on Orillia’s Judge McCosh (whose fictional daughter, Zena McGaw, appears nominally in the subsequently revised title of the eighth story in the Star, as can be seen in Figure 1), and so forth. Leacock’s first biographer, Ralph Curry, writes that between serialization and book, Leacock’s Orillian friend Judge Tudhope “had written him a letter righteous with mock indignation, threatening to sue him on behalf of the town of Orillia. Leacock enjoyed the letter, but the publishers grew cautious and made him change the names” (Curry 98-99). I have not been able to locate any evidence supporting Curry’s justification of the revision, and I doubt anyway that Leacock could have been made to do anything, or that his British and Canadian publishers were wary of the actual townsfolk’s legal proceedings based on a work of humorous fiction.

8 What is more likely, and more significant, is that Leacock would not have wanted to give such particular offence. That may sound paradoxical, even contradictory, applied to such a gifted humorist-satirist, but in his many writings on comic literature (including two books), Leacock stated repeatedly that humour should be kindly. In his post-humously published unfinished autobiography, The Boy I Left Behind Me, he revealingly (and rarely for Leacock) related an incident from his student days of having given offence with his gift for mimicry, an unintended offence that taught him “how not to be funny, or the misuse of a sense of humour which lasted me all my life” (159-60). In Humour and Humanity: An Introduction to the Study of Humour (1937), he defined humour as “the kindly contemplation of the incongruities of life, and the artistic expression thereof” (15). The American satirist S.J. Perleman, among others, supposedly said that Leacock’s definition, with its stipulation of kindliness, was an impossible condition. And Robertson Davies believed that the unfavourable Orillian response to Sunshine Sketches forever constrained Leacock’s natural gift for satire (27, 45, 56). In the first instance, those of Perleman’s persuasion fail to understand that by “kindly” Leacock did not mean gentle, only that the ultimate purpose of humorous literature should be an acknowledgement of shared humanity, of kinship — equally kin with regard to folly and kind with respect to tolerating it. Leacock could and did write pointed satire when his subject warranted such treatment, as Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich (1914) demonstrates. That book can serve, too, in answer to Davies’s unfounded claim, since the Adventures was published two years after the Sketches.

9 Apart from the comparatively minor matter of names, and after the major restructuring of the sketches (discussed below), the most significant substantial revision from serialization to book occurs at the end of “The Beacon on the Hill,” the third and final of the sketches on religion in Mariposa. In the Montreal Daily Star, the religious sketches end (after the mistaken Church of England Church has been burned down for the insurance money and a yet more ostentatious edifice erected in its place) with this leave-taking of the Rev. Mr. Drone, who apparently has suffered a stroke: he “can read with the greatest ease works in the Greek that seemed difficult before. Because his head is so clear now” (“The Ministrations of Cannon Drone” 23). McClelland and Stewart’s New Canadian Library edition of Sunshine Sketches, the text most used in classrooms, as well as that more recent British edition introduced by Richler, makes the last fragmentary sentence, “Because his head is so clear now,” a concluding subordinate clause, replacing Leacock’s penultimate period with a comma. The correct version, by setting apart the “because” clause as a concluding sentence, pointedly questions the “clarity” of Drone’s post-stroke mind both tonally through irony and grammatically with the “broken” sentence fragment. Not to put too fine a point on it, the original close of “The Beacon on the Hill” in its serialized version in the Star effectively leaves the Rev. Mr. Drone in a condition of idiocy.

10 The first edition of Sunshine Sketches, whose page proofs Leacock corrected in Paris (which in itself is interesting), retains the serial’s appraisal of the Rev. Mr. Drone, punctuated correctly. However, Leacock appended this new closing paragraph: “And sometimes, — when his head is very clear, — as he sits there reading beneath the plum blossoms he can hear them singing beyond, and his wife’s voice” (148). There is some evidence that Leacock added this pathetic closing touch in response to his mother’s unfavourable reaction to the thinly disguised depiction of her gentle Orillian minister, Canon Green. 3 And note (see Figure 1) the attempt at disguise from serialization to book in the change from “Canon” to “Rev. Mr.” It would be mistaken, though, to draw from the biographical story an inference (as Davies does) of Leacock’s lack of artistic integrity. As stated, Leacock believed that true humour, kindly humour, operated between the satiric and the sentimental, utilizing pathos, as here, to blunt the point of aggressive satire (Leacock, Humour and Humanity 232-33). In the instance of the three sketches on religion, which end disastrously for Mariposa, the humorous satire against Drone is harsh indeed. The pathetic reference to his dead wife and his own approaching death, added for the book, admirably serves the humorous purpose of the conservative humanist Leacock.

11 With that understood, the original ending of the religious sketches, where Dean Drone is literarily punished for his sins, nonetheless supports a view that the seemingly gentle and befuddled Drone, and not Josh Smith (the most obvious candidate), is the true villain of Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town. Smith’s individualistic drive for wealth and power can be tolerated, can even be unintentionally beneficial, in keeping perhaps with the supposed “invisible hand” of the laissez-faire economic theory of his namesake, Adam Smith. 4 Gentle, villainous Drone is the passively aggressive prime mover whose vanity, foolishness, literal-mindedness, incompetence, and dishonesty shading into criminality (he veritably embezzles church funds [56-57]) insidiously deprive Mariposa’s Anglicans of a true spiritual home, first in the “sacrilegious” demolition of its “little stone church,” which, “like so much else in life, was forgotten” (58), and then in the unaffordable building of the new church. For being so, and more so in Leacock’s first conception in serial publication, Drone gets whacked. That he is somewhat redeemed in the pathetic close of the revision testifies to Leacock’s belief in, and adherence to, his own original conception of humour and its purposes: “Humour is saved from [indifference, cruelty, and self-indulgence] by having made first acquaintance and then union with pathos, meaning here, pity for human suffering” ( Humour and Humanity 232-33).

12 Turning to the larger revisions made from serialization to book, I direct readers again to Figure 1. Leacock made three major structural changes for book publication. He added the aforementioned autobiographical preface and rearranged the sketches as follows: the first two instalments for the Star, “Mariposa and its People” and “The Glorious Victory of Mr. Smith,” were combined to form the book’s opening story, “The Hostelry of Mr. Smith”; and the sixth instalment for the Star, “Mariposa’s Whirlwind Campaign,” was divided to become the fifth and sixth stories in the book, “The Whirlwind Campaign in Mariposa” and “The Beacon on the Hill.” As observed, the addition of the preface adds symmetry, in that it, with “L’Envoi: The Train to Mariposa,” provides an authorial frame for the sketches proper (see Figure 1). That is, the preface and “L’Envoi” offer the reader different, though complementary, perspectives on Mariposa and Sunshine Sketches itself, perspectives that differ not only from one another — in being autobiographical and anticipatory as opposed to sombre and reflective — but also from the perspective of the narrator of the sketches proper (1 through 11). The central narrator is very much of the narrative’s fictional present time: he lives in Mariposa (in fact he introduces “you,” the reader, to the town as if he were a tour guide [1-5]), though he also possesses experience of the cosmopolitan world beyond. 5 All three perspectives — those of the author of the preface, the involved narrator of the sketches proper, and the reflective narrator of “L’Envoi” — are necessary to Leacock’s rounded view of Mariposa and Sunshine Sketches itself; the “L’Envoi” narrator refers self-reflexively and materially to Sunshine Sketches when he imagines his silent auditor “sitting somewhere in a quiet corner reading such a book as the present one” (141).

13 In that book, the revised sketches proper can be grouped into five thematic sections (excluding the authorial frame composed of preface and “L’Envoi”).

- Sketches 1 and 2, concerning the adventures of Josh Smith and Jefferson Thorpe, deal with real and illusory business practices respectively, with the climax of the first sketch (19) including the important anticipation of the political concerns of the last two sketches; that adumbration of the political sketches is key to understanding Josh Smith’s deceptive philanthropic and heroic actions throughout the stories: he is not only always acting in his own interests but also already campaigning from the first sketch onwards.

- Sketch 3 utilizes the ship trope to portray in microcosm the social life of Mariposa in the excursion aboard the Mariposa Belle.

- Sketches 4 through 6 deal with religion.

- Sketches 7 through 9 portray Mariposan romance, love, marriage, and family.

- Sketches 10 and 11 depict political machinations in Mariposa.

13 With reference again to Figure 1, readers can see that the four-sketch business and political sections of the book — sketches 1 and 2, 10 and 11 — contain the social, religious, and romantic dimensions of life in Mariposa, acting as a kind of fictional frame within the authorial frame formed by the preface and “L’Envoi.” This is what might be expected in the fiction of a conservative political economist; of course, in his added autobiographical preface, Leacock states flatly, “In Canada I belong to the Conservative party” (xvii), having dwelled ironically on his academic credentials as a McGill professor (xvi). Such a writer’s priorities offer a reason why the social-microcosm sketch, “The Marine Excursion of the Knights of Pythias,” does not come first, following the introduction of the town, as might be expected. That is to say, the overall organization of the sketches proper — and most purposefully in their restructuring for book publication — bodies forth Leacock’s priorities: the realities of business and politics come first and last, an interior frame or, with the authorial preface and “L’Envoi,” like a doubled scaffolding. And at the centre of the book, its material and fictional heart, are the spiritual realities of religion and love.

14 By reorganizing and retitling the opening sketches, Leacock gave prominence to the character of Josh Smith, who then dominates both the opening and close of Sunshine Sketches (excepting “L’Envoi”) like a dangerously clownish colossus bestriding the favoured Maripsoa. By reorganizing the middle sketches, Leacock created in the interior of the book — sketches 4 through 9 — two three-sketch sections, two triptychs of a kind, of which the first reflects Mariposan religion and the second, Mariposan romance. This contrived symmetrical centre of Sunshine Sketches opposes three sketches on the failure of Mariposa’s institutionalized Anglican religion to meet simply the needs of its parishioners with three sketches on the triumph of Mariposan romance, love, marriage, and family.

15 It is tempting to wonder if Leacock, commissioned to write this series of humorous sketches for newspaper serialization, did not pause at the original conclusion to “The Beacon on the Hill,” the approximate halfway point of fulfilling his commission, and wonder just where he had got to and where he would go. If he did so, he might have been prompted to pause not only by the spiritual travesty that ends the section on religion and the sad case of culpable “Canon Drone” with his addled brain, but equally, and perhaps more so, by the sorry state of Mariposan life generally at this point. These were supposed to be sunshine sketches of a Canadian little town, and here at mid-point Mariposa has fallen monstrously to the nadir of darkness: its Anglican minister is at best a simpleton and at worst corrupt; communal Mariposa has engaged materialistic, individualistic Josh Smith to burn down its bankrupt Church of England Church for the salvific insurance money; and the sketches on religion have climaxed in a blanketing darkness of parodic Crucifixion proportions: “Then when the roof crashed in and the tall steeple tottered and fell, so swift a darkness seemed to come that the grey trees and the frozen lake vanished in a moment as if blotted out of existence” (79). Compare the evangelist Mark (15:33) on the moment of Christ’s death: “There was darkness over the whole land.” 6

16 Of course, without evidence, no critic can know what was in Leacock’s mind in the winter and spring of 1912 as he serialized and then revised Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town. But it is conceivable that Leacock, experiencing readers’ responses to his sketches as they were appearing in the Montreal Daily Star, including the unfavourable response of his beloved mother to the portrayal of her Orillian minister, and in light of his specific commission, may well have surprised even himself when he recognized where he had landed Mariposa and his newspaper readers: in darkness and spiritual despair, with the central figure of his fiction, the town of Mariposa, under complete erasure, “blotted out of existence.” If that had been the case, a writer such as Stephen Leacock would have realized the need for something redemptive following the failure of religion. But whatever the circumstances may have been, his revision of the organization of the sketches from serialization to book — those now facing triptychs — highlights a counterbalancing between religion and romance, most likely a compensatory relationship. Following his anticipation of the failure of traditional religious institutionalism in the coming twentieth century — recall that Mariposa is Canada at that time, not only as per the conditions of Leacock’s newspaper commission but also in the opening of the first story: “I don’t know whether you know Mariposa. If not, it is of no consequence, for if you know Canada at all, you are probably well acquainted with a dozen towns just like it” (1) — what better salvation for the humanist Leacock to offer than human love. 7

17 Leacock, of course, has brilliant parodic fun with the Zena Pepperleigh–Peter Pupkin romance in sketches 7 through 9. But it is as important to recognize that the “puppy-love” romance sketches begin with the mature married love of Judge Pepperleigh and his wife, a love that sustains them through the decidedly unfunny death of their son, Neil, in the Boer War (87). Moreover, it is noteworthy that the opening of the romance sketches deals also with the love of the parents for their children, Zena and Neil. The romance sketches are also about real love, then, mature sustaining love, and, in view of the preceding three sketches on the loss of true religion, redemptive human love. If the religious sketches brought Mariposa and Sunshine Sketches to their darkest moment, the romance sketches “irradiate” (92) the town with the titular sunshine. The big bang moment occurs in the passage describing Peter’s sighting of Zena and is worth quoting at length. Observe in the following passage the skill with which Leacock uses point of view, moving from initial ironic distance to unqualified, un-ironic endorsement, the seriousness of which he highlights with a Dickensian direction to readers to pause and reflect on what they have just witnessed:

17 Here “the past is all blotted out,” with no past more immediately in need of corrective counter-blotting than that which has just occurred with the toppled steeple of the church. As in the traditional romantic conception of love’s beginning, the first strike is purely visual, darting through the eye en route to the heart: Zena is a pretty girl, and for that “commend me to the month of June in Mariposa.” The narrator knows that the preferred place, the small town, Mariposa, is essential to this process: “The whole town [is] irradiated with sunshine.” Here is that titular instant of illumination, Leacock’s conservative-humanist singularity, in which he also employs his definitive word for humour, “kindliness.” In other words, the kindly vision, whether of humorous literature or human beings, is dependent on a loving predisposition. One must have one’s heart in the right place, as all comes home to place: “only those who have lived in Mariposa, and been young there, can know at all what he felt.”

18 The structurally manipulated, balanced opposition between failed religion and successful romance at the centre of Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town alone demonstrates that Leacock’s masterpiece is a highly organized short story cycle (Lynch, Leacock on Life 26-31), a complex work of literary art, and the best illustration of Leacock’s claim in its preface that true humorous literature is an “arduous contrivance” (xvii). Leacock’s architectonic genius was never again as impressively displayed as in this work that should be recognized as the first masterpiece of Canadian fiction: from its framing autobiographical preface expressing concern for the fate of the Canadian small town, to the metropolitan Mausoleum Club of “L’Envoi” with its layering of points of view on the increasingly abstract figure of “Mariposa,” to the interior opening and closing frame tales of business and politics (fairly interchangeable institutions in Leacock’s informed vision — and what prescience is evident in that anticipation of the twentieth century’s increasing reliance on image politics), to that essentially spiritual confrontation contrived for the centre of the book. Thus it proves instructive, and perhaps even fascinating, to recognize some of the ways in which Leacock’s revisions to Sunshine Sketches from serialization to book in 1912 can bring into clearer focus its author’s intentions and comic vision of human frailty and responsibility at the start of modern times.

I am grateful to Nadine C. Mayhew for her help with Figure 1.