Articles

Anne Shirley, Storyteller:

Orality and Anne of Green Gables

Trinna S. FreverUniversity of Michigan

1 ANNE OF GREEN GABLES, and its author L.M. Montgomery, claim a strong affiliation with print literary traditions. Montgomery read avidly from a wide range of books, as her journals attest, and this varied reading is reflected in her literary style. The late Rea Wilms-hurst documented the massive web of intertextual references present in the Anne series alone. Elizabeth Epperly’s groundbreaking The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance remains a benchmark in Montgomery scholarship for its thorough analysis of romantic/Romantic literary influences upon and within Montgomery’s texts. Harvesting Thistles: The Textual Garden of L.M. Montgomery speaks directly to Montgomery’s varied textual affiliations, and more recent works continue to develop the complex, intricate use of intertextuality resonant within her writing.1

2 Yet scholarly emphasis on the literary affiliations of Anne of Green Gables belies an equally significant, and abundantly present, narrative influence on Montgomery’s work: oral storytelling. Little critical attention is paid to Montgomery’s strong personal bond with the spoken word, as expressed within her journals and novels, and particularly within Anne of Green Gables. The presence of this second layer of narrative style, an intermingling of oral and print literary techniques, heightens the complexity of Montgomery’s literary project. While oral and print narratives are often at odds, Montgomery manages to create a smooth flow between print and orality, aligning herself simultaneously with great authors of literary tradition — Shakespeare, Scott, Byron — and with the oral storytellers of Scottish tradition, as well as the less formalized storytelling practices of families and rural communities.2 This dual, oral-print affiliation is an important component of Montgomery’s broad international appeal, spanning nearly a century of avid readership. She fulfills the roles of both literary great and local storyteller, drawing in the audiences of each of these narrative-weavers, and in the process, crafting a work that fulfills the functions served by both traditions: to educate, to uplift, to heal, to challenge, to soothe, to entertain, to delight. An understanding of Montgomery’s use of and affiliation with oral storytelling in Anne of Green Gables is key to understanding her narrative style, the relationship created between reader and text, and thus the novel’s far-reaching appeal. These effects are achieved primarily through the depiction of Anne Shirley as a storyteller.

3 Any reader of Anne of Green Gables knows that Anne is a talker. The memorable drive from Bright River with Matthew, where Anne talks uninterrupted for a page and a half, and with scant interruption for another five beyond, sticks out vividly within the text.3 Indeed, though Anne’s talkiness is portrayed as a “trial” to some of the characters in the novel, it is one of the most appealing aspects of Anne’s character according to Matthew, Diana, and numerous readers. But outside of Anne’s ability to charm listeners with her “quaint speeches” (236), Anne’s characterization as a chatterer serves several important functions within and outside the text. This depiction overturns the long-standing Victorian childrearing adage that “children should be seen and not heard,” as the novel was released at a time when childrearing practices were shifting (Waterston and Rubio, 308). Anne’s vocalness reinforces the importance of female voices, and the opinions contained therein, in the home, the school, the church, and the community. Anne has featured scenes of speaking out in each of these settings, and each time it is a confirmation of her significant role as a talker within the larger Avonlea setting.4 In addition to the social functions of Anne’s speech, her talking serves a narrative function as well, by aligning the text with oral storytelling traditions and the narrative importance of the voice. Several affiliations to orality appear within the text of Anne of Green Gables — vocal and physical performance, fairy story, gossip, ghost story, Greek myth, reading aloud, recitation, healing story, community story — and each of these narrative traditions, with its distinct style, comes to bear on the larger framework of the novel, aligning Montgomery’s text with minstrels and oral storytellers as well as their authorial counterparts. Anne is the centre of each and all of these narrative effects.

4 Storytelling differs from print text on several levels. As Walter Ong argues, print is by nature linear and fixed, decoded by reading lines across a page, and its narratives focus upon “strict linear presentation of events in temporal sequence” (147). Moreover, while interpretations of a written text can vary, the text itself is identical upon each reading: “Though words are grounded in oral speech, writing tyrannically locks them into a visual field forever” (Ong 12). The spoken voice in storytelling, by contrast, is spatial rather than linear, and ephemeral rather than fixed. Sound fills the air, and yet each time a story is told, it may resonate differently with unique word choices, volume, inflection, and other characteristics of performance.5 Print and storytelling also feature differing relationships to their audience, with print “speaking” to individual readers in a silent, visual code, and storytelling speaking to a physically present audience that interacts with the teller and tale as the tale unfolds. These disparate qualities lead to different narrative aesthetics and styles for print and oral story, such that the values of one (a clear plot that follows an individual character, for example) and the values of another (a rich soundscape, the ability for the audience to emotionally connect with both teller and tale simultaneously) create different types of stories, different measures for judging narrative success and importance, different modes of communicating their themes, and in some cases, different cultural values as well.6 When Montgomery brings the elements of oral storytelling to bear upon her print text, it creates a polyvocal narrative style, whereby the voice of Anne as storyteller runs parallel to the voice of the print narrator, collapsing the hierarchical levels of narrative that place author-narrator-reader as a descending chain of power in the literary act, and that distinguish between “real life” and the told tale, thus recuperating the reader into the communal experience of a listening audience that oral storytelling represents.7

5 When Anne talks, it is not a random event within Anne of Green Gables. Her speech forms a pattern across the text, a structural thread that binds isolated incidents together, lending coherence to the novel as a whole, drawing the reader into Anne’s world through her storytelling, and establishing the relationship between text and reader as one of speaker and listener within an oral storytelling tradition. Anne’s introduction in the novel is accomplished through a long monologue, followed by a reaction from her audience in the novel (in this case, Matthew Cuthbert). This introduction sets up a pattern of monologue/reaction within the text. Anne tells a long series of observations or a set of interconnected anecdotes to a listener, and by extension, to the reader of the book, who becomes the audience of her speech alongside the in-book listener. The in-book listener then comments, not so much on the content of her speech, but on the fact of the speech itself, calling attention to Anne’s talkiness in general, and emphasizing the narrative technique at play. Anne is established as an oral storyteller to the characters within the book, but also to the readers of the book, who are drawn into an oral storytelling moment, and a closer connection with Anne herself, through the narrative act.

6 The most common form for the monologue/reaction format in the book is for Anne to talk to Marilla for a long, uninterrupted duration — one is “ten minutes” by Marilla’s clock (93) — and then to receive a reprimand from Marilla for her chattiness. An early example of this pattern occurs when Anne relates the details of her life prior to arriving at Green Gables. At Marilla’s prompting, Anne tells inset stories — sub-stories within the larger narrative of the book— of her parents’ life before her birth, her parents’ death, her life with the Thomases, the death of Mr. Thomas, her life with the Hammonds, the death of Mr. Hammond and departure of Mrs. Hammond, her life at the Hopeton orphan asylum, and her educational history, as well as offering an evaluative critique of her various guardians’ maternal abilities.8 This relating of events goes on for loosely three pages of text, with only brief interruptions from Marilla to guide the content of the narrative. These inset stories mark Anne as a storyteller and narrator in her own right, alongside the omniscient narrator who opens the novel. Each of these stories is a miniature narrative in itself, including major life events such as birth, death, the breakup and reforming of families, and immigration. Though the stories are conveyed as part of Anne’s own history, they point to a world of stories outside Anne’s own, with Anne as their storyteller. As is common with both real-life communities and storytelling within print texts, Anne is also established as a link in a chain of storytellers, rather than a lone storyteller unto herself. Several of the events Anne relates, most especially her parents’ courtship and her own birth, would be impossible for Anne to know firsthand. Rather, she is told these tales by Mrs. Thomas, as emphasized by the frequent repetition of the phrase “Mrs. Thomas said” (39). One gleans immediately through Anne’s narration that Mrs. Thomas is neither as benevolent nor as intelligent as Anne herself, but it is still apparent that Mrs. Thomas too has “got a tongue of her own” (11), and the chain of narration that passes from Mrs. Thomas to Anne reinforces Anne’s role as a storyteller in the traditional sense, and not merely an avid conversationalist.

7 Further, Anne’s interaction with Marilla in this exchange bears the marks of a storytelling moment, rather than a mere conventional dialogue. First, of course, is the content of the tales. Anne does not simply give information; she tells stories, stories with entire life histories behind them, and vested with her own observations and reflections, to guide the reader toward the interpretative act. Anne’s verbal relationship with Marilla, one that continues for the breadth of the book, is defined in this exchange. Though Marilla intervenes periodically, and Anne’s story adapts to her intervention (a technique not uncommon in oral storytelling communities), Anne’s voice is the dominant one. Their exchange is not really an exchange. Anne talks; Marilla listens. Anne is the storyteller; Marilla is her audience. Montgomery’s narrative choice places the reader in Marilla’s shoes. These same details of Anne’s pre-Avonlea life could easily have been conveyed by the omniscient narrator established early in the novel, as in “and then Anne related the details of her life with the un-sympathetic Mrs. Hammond….” This narrative technique of relating Anne’s tales second-hand would be an equally viable choice, if the orality of the larger narrative, and the establishment of Anne as a storyteller, were not at stake. Instead, Montgomery provides the reader with page after page of Anne’s voice, speaking. Her choice recuperates the reader into the audience of Anne’s narration, as if in the room with Anne and Marilla, rather than outside it reading a book. Montgomery uses orality to erode the distancing inherent in the print narrative act, and recasts her audience as listeners to the voice of Anne-as-storyteller. This technique also provides the readers with information about Anne as a storyteller: her word choice, her speaking style, the cadence of her sentences, her narrative frames of reference. Though Anne may talk like a book, the early establishment of her voice, its style and its quantity, verifies the novel’s strong engagement with oral tradition alongside its print affinities.

8 Marilla serves three primary roles in these exchanges. First, she listens to Anne virtually uninterrupted. Indeed, her interruptions become less and less frequent as the novel progresses. Second, she reprimands Anne for her long speeches, but in so doing, establishes her third and most crucial role: to call attention to the speeches themselves. In the aforementioned example, Marilla does not reprimand Anne directly. Instead, she thinks aloud that Anne’s “got too much to say” but that “there’s nothing rude or slangy in what she does say” (41). Though Marilla’s comments appear negative, they serve to reinforce Anne’s verbal ability by calling attention to it. Moreover, these comments open the door for disparate audience readings. Readers, who have just experienced the same speech as Marilla, almost in “real time,” are able to judge Marilla’s evaluation of Anne’s oration, and agree or disagree accordingly.9 Some will likely agree that Anne talks too much, but will find her speech charming rather than cloying. Others, advocates of the then-new childrearing theories, budding feminists, and/or talkers themselves, may feel that Anne talks just the right amount. Doting Matthew, we know, cannot hear Anne talk enough, and “the more she talks and the odder the things she says, the more he’s delighted” (90). Doubtless some readers fall into his interpretative camp as well. Indeed, even Marilla is more sympathetic than she permits herself to appear. The narration tells us that “Marilla permitted the ‘chatter’ until she found herself becoming too interested in it, whereupon she always promptly quenched Anne by a curt command to hold her tongue” (63). Regardless of the individual reaction, Marilla’s observations invite readers to share her interpretive audience position, and reinforce Anne’s position as storyteller. Marilla’s parting comment on Anne’s speaking style as “ladylike” and not “slangy” again draws attention to Anne’s verbalness by reinforcing the spoken qualities of her speech (41). Thus Marilla’s seeming reprimands actually reinforce the storytelling moments in the novel, strongly confirming Anne’s position as orator, and recreating the reading audience as active listeners to the stories of Anne.

9 As the novel progresses, Marilla’s post-monologue comments about Anne’s speech are directed toward Anne herself, though in a narrative wink, these comments do little to stem the tide of Anne’s storytelling. When Anne tells us the experience of her first prayer, Marilla counters: “When I tell you to do a thing I want you to obey me at once and not stand stock-still and discourse about it” (55). When Anne reflects on the Lord’s prayer itself, Marilla tells her to “learn it and hold your tongue” (57). When Anne tells of her imaginary friends Katie Maurice and Violetta, and speculates on the experience of living in an apple blossom (a probable reference to Anderson’s Thumbelina and/or The Rose Elf), Marilla notes that “it seems impossible for you to stop talking if you’ve got anybody that will listen to you” (59). This reprimand becomes doubly ironic when we realize that we too are Anne’s listeners, due to the narrative style, thus giving Anne free license to talk all the time. The second irony lies in the fact that this speech of Anne’s has doubled or even tripled in length from the ones receiving the previous reprimands. Even within the context of the novel, Marilla’s words serve to confirm, rather than deter, Anne’s storytelling abilities.

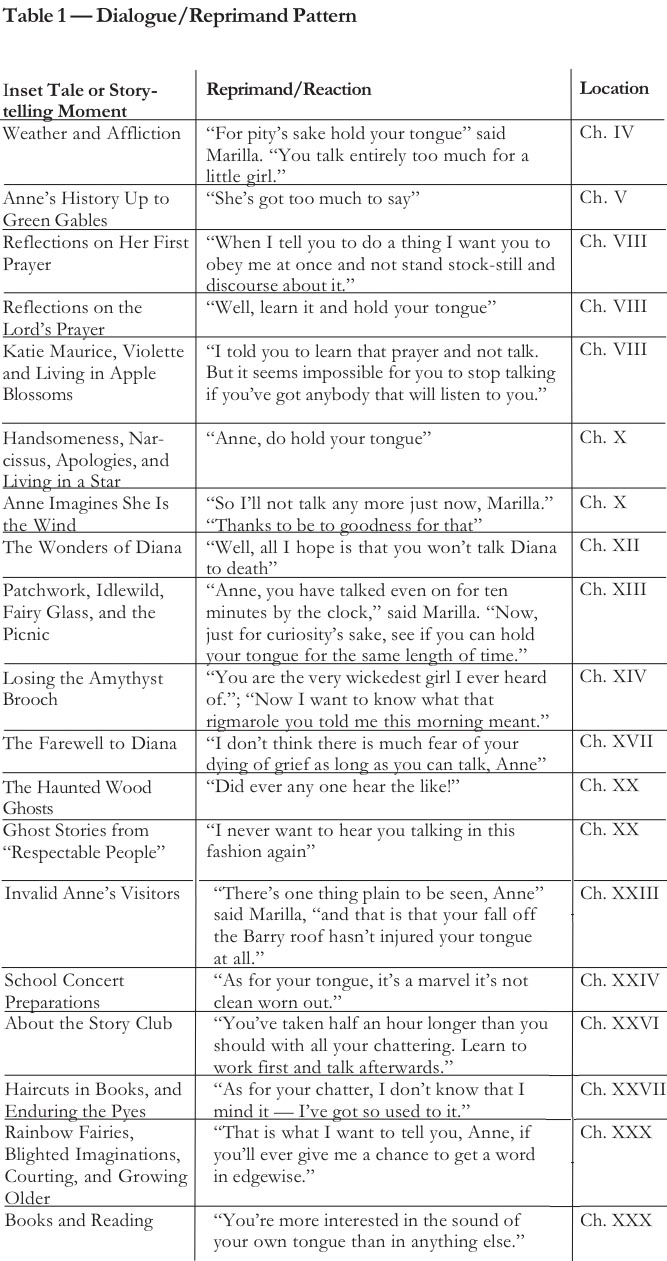

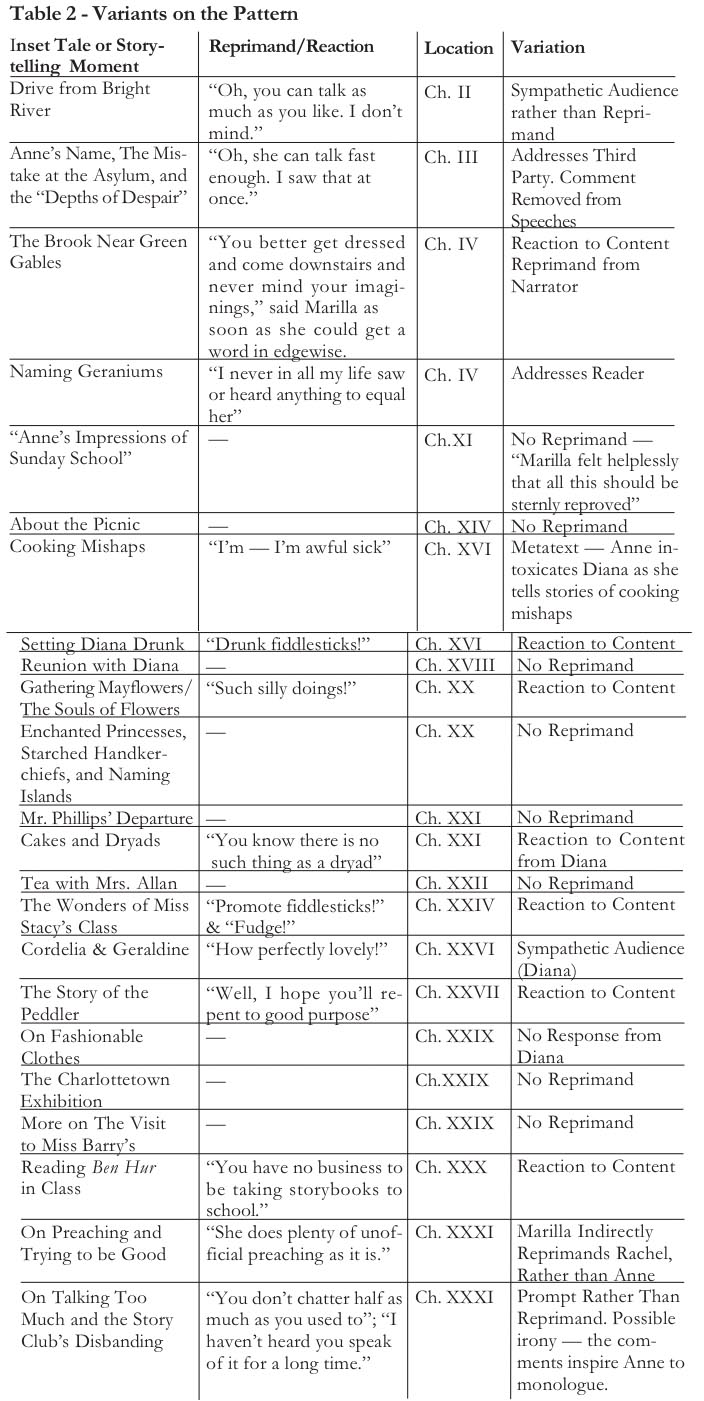

10 This monologue/reprimand pattern appears at least nineteen times in the novel, and slight variants to the pattern account for an additional twenty-three or more episodes (see Table 1 and Table 2). Each of these moments is presented in Anne’s voice, uninterrupted for anywhere from a paragraph to three pages, and each time Marilla’s comments serve the same function: to remind us that Anne is a talker, a storyteller, and to reinforce the listening act we readers have just experienced (see Table 1, column 2). Anne’s themes go largely unquestioned; her voice itself is what receives Marilla’s supposed scorn, until Marilla herself finally admits that she has “got so used to it,” which is translated by the omniscient narrator as “Marilla’s way of saying that she liked to hear it” (219). Once again, Marilla’s speech draws attention to Anne’s role as storyteller and her own role as interpretative audience, reinforcing the reading/listening audience’s own role in the storytelling process. This act defines an interpretive storytelling community around Anne, both within and outside the novel, refocusing the relationship of reader to text, and aligning Anne with oral tradition, through the novel’s narrative process.

11 The narrative structure as a whole represents a fluctuation between Anne’s voice, the voices of the other characters in the novel (often storytellers themselves), and the voice of the omniscient narrator. Since Anne speaks a long monologue in nearly every chapter, the novel can be interpreted as polyvocal, representing a fusion of voices rather than a single, dominant narrative voice guiding the text.10 Aside from its narratological implications, this presentation of Anne as alternate narrator through her storytelling affects her characterization and her impact upon the reader. For instance, some of Anne’s mishaps or “scrapes” within the novel are conveyed by the omniscient narrator, like the episodes with Mrs. Allan and the liniment cake, and the scene where Anne falls from the ridgepole of the Barry’s kitchen roof. We “witness” these scenes as they happen, guided by the narration that forms a counterpoint to Anne’s voice. Yet many of the key episodes of the novel are presented by Anne’s narration, rendered through her perspective and speaking style, including the scene of the mouse drowning in the plum pudding sauce, the farewell and reunion with Diana, and the visit to Miss Josephine Barry that Anne claims is an “epoch” in her life (125; 132-33; 146-47; 233-37). This narrative technique allows the reader to experience Anne’s antics doubly: once in themselves, and once in the telling.

12 Though they are not actually presented twice, Anne’s retelling of events intensifies their Anne-ness: we see her mishaps, and evidence that she is a delightfully “odd little thing” (74), through the events themselves, and again through the style of Anne’s speech. For example, when Anne allows the tainted pudding sauce to be served because she is imagining that she is “taking the veil to bury a broken heart in cloistered seclusion,” we recognize both the event and its phrasing as vintage Anne (125). Likewise, when Anne burns a pie for Matthew’s dinner, and she informs us that “an irresistible temptation came to me to imagine I was an enchanted princess shut up in a lonely tower with a handsome knight riding to my rescue on a coal-black steed. So that is how I came to forget the pie,” it is the combination of the event itself and Anne’s verbal rendering of it that lend uniqueness and charm to the character of Anne herself (162-63). No mere horse for Anne-with-an-E, a “coal-black steed” must be the mount that gallops through her daydreams. The very Anne-ness of being overcome by an “irresistible temptation” to imagine, even when specifically endeavouring not to, is brought home to the reader through the phrase itself as much as the described action. Elizabeth Epperly refers to such moments as “Anne’s vocal self-dramatizations,” and notes how “Anne of Green Gables is charged with the rhythm and energy of Anne’s voice and personality” (17, 18). Anne becomes the interpreter of her dreamworld to Marilla, and to the readerly world, and thus her effect on the reader is doubled through the use of voice. Whatever feelings are evoked for Anne during the reading of the novel, they are evoked twice: once for the event itself, for Anne’s marvelous capacity to get into “scrapes,” and again for her characteristic verbal style in the retelling. Indeed, Anne’s skills as a storyteller are not slight, and far exceed her apparent skills in cooking. Her word choice, use of descriptive adjectives, inventive and/or adventurous plotlines, and aptitude for impromptu creation, all establish Anne as a master storyteller. True, many of her storytelling techniques, including her distinctive vocabulary, are strongly influenced by print fiction (see Epperly; Wilmshurst). Nonetheless, it is Anne’s voice, and her vibrant storytelling style, that win the day.

13 While the structural use of the inset tale featuring Anne as narrator would be enough to classify Anne as a storyteller, the content of Anne’s speeches, along with her function as storyteller within the community, reaffirm Anne’s role in a larger world of story. She is aligned with storytelling traditions that exist outside of the novel itself, connecting her intertextually and extra textually to oral tradition. Of these, the two most prominent oral traditions are the world of fairy (or Faerie), and the role of the community storyteller. Elizabeth Epperly’s work identifies Anne’s strong connections to landscape, and to knight/maiden imaginings, and contextualizes these qualities within literary tradition. While thorough and masterful in its analysis, the identification of Anne with print-based romanticism erodes an earlier identification. Each of these qualities of nature and romance comes to print from an even older story source: oral tradition. Tales of knights and maidens and little creatures hiding in the green woods exist in fairy and folk tale long before their particular manifestation in the creative works of Keats, Scott, Mallory, or Rosetti. So the same qualities that place Anne within a print tradition, when recontextualized, place her equally within the oral traditions of the fairy and the folk tale.

14 Culturally, Anne’s fairies and folk stories draw from Scottish, Danish, and other European and Asian traditions, as well as her own imagination.11 Through these connections, Anne is established not only as the subject of one tale, Anne of Green Gables, but as a teller of tales of her own, a creator in her own right, within the larger tradition of the fairy tale that exists outside the novel itself. It is here that the content of Anne’s tales becomes preeminent in her characterization as an oral storyteller. For example, Anne’s previously noted reflection about living and sleeping “in an apple blossom” (59) is strongly reminiscent of Hans Christian Andersen’s “Thumbelina,” wherein “right in the middle of the flower, on the green centre, sat a tiny little girl, graceful and delicate as a fairy” (14-15), and also his Rose Elf, who “dwelled” in a flower-house wherein “behind each petal of the rose he had a bedchamber” (103). Though Anne seems unselfconscious in her referencing, she is established as a teller within a tradition of fairy tales through her references. Such references abound throughout Anne of Green Gables, each one tying Anne to the oral tradition of the fairy story that exists outside the novel that seemingly contains her.

15 Another example comes couched inside the more gritty, true-to-life tale of Mrs. Thomas and her drunken husband. It is Anne’s fanciful tale of the “enchanted” bookcase, whereinif I only knew the spell I could open the door and step right into the room where Katie Maurice lived…. And then Katie Maurice would have taken me by the hand and led me out into a wonderful place, all flowers and sunshine and fairies, and we would have lived there happy for ever after. (58)Though the tale is Anne’s own, it claims a strong affiliation with oral traditions outside the text. Anne’s bookcase story is reminiscent of more than one tale from A Thousand Nights and a Night (also called “Arabian Nights”), where magic doors are opened with magic words. It also evokes The Pied Piper, where children are promised entry into a magical land through a hidden door, and indeed references all tales that describe a world of “flowers and sunshine and fairies.” Anne’s tale precedes The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe, The Hobbit, and other books wherein magic words open magic rooms, and everyday furniture holds a hidden world. As such, Anne creates herself as a teller in the midst of a temporal flow of stories — stories about magic and fairies and spells and secret rooms — that exist before, after, and outside Anne of Green Gables. Katie Maurice and The Enchanted Bookcase is one of Anne’s contributions to this larger fairy world, and her ritualized language of “happy for ever after” weds her tale to the tradition from which it draws, and to which it contributes (58).

16 Like most storytellers, Anne creates some of her tales, and tells other tales from within a pre-established tradition, adding only her unique spin in the telling, as when she must entertain Matthew while he waits for the tea that Anne herself was meant to brew:I told him a lovely fairy story while we were waiting…. It was a beautiful fairy story, Marilla. I forgot the end of it, so I made up an end for it myself and Matthew said he couldn’t tell where the join came in. (121)Whether creating or adapting, Anne’s role as a storyteller and her close acquaintance with fairy tale traditions are firmly established through numerous storytelling episodes like this one. Whether Anne tells us she is “imagining that I was a frost fairy going through the woods turning the trees red and yellow, whichever they wanted to be” (125), or that “All the little wood things — the ferns and the satin leaves and the crackerberries — have gone to sleep, just as if somebody had tucked them away until spring under a blanket of leaves. I think it was a little gray fairy with a rainbow scarf that came tiptoeing along the last moonlight night and did it” (239), Anne’s entrenchment in the fairy world, and her role as teller of fairy stories, reaffirms Anne’s position as a pillar of oral tradition.

17 Even outside the world of fairy, Anne’s characterization as a storyteller is conveyed through her performative skills, and her role as a purveyor of community information … a teller of Avonlea and island tales, as well as her own. This second context, that of the community storyteller, carries many similar effects to that of Anne’s fairy-world, in terms of her characterization as a storyteller. It is not uncommon for small, rural communities in the era prior to telephones and automobiles to have been driven by word-of-mouth news, and we know that in Montgomery’s own life, “Maud’s home was a gathering place for exchange of news, gossip, and local anecdote, all nourishing the love of a good story” (Waterston and Rubio 309-10). This back-fence orality is another category of storytelling, and is referred to as such within the novel. When Anne offends Rachel Lynde with her tempestuous insults, Marilla indicates that “Mrs. Lynde will have a nice story to tell about you everywhere — and she’ll tell it, too” (67). Again, when Anne is unjustly punished by Mr. Phillips at school, Marilla speculates that “Far as I can make out from her story, Mr. Phillips has been carrying matters with a rather high hand” (117), and when Marilla decides to seek Rachel Lynde’s counsel, she notes, “She’ll have heard the whole story, too, by this time” (117). Indeed, with its speed and efficiency at circulating a hot story, Avonlea knows no need of print.12 Though Anne herself takes up a position in the community of stories, they exist prior to her arrival. Indeed, when Anne sets foot in the Green Gables kitchen, she is entering not only into Avonlea and Green Gables life, but into the storied context that precedes her.

18 Anne arrives at Green Gables through the cause of orality. Though we do not learn it until Chapter VI, the Cuthberts receive Anne, rather than the originally desired boy, because their message is “passed along by word of mouth” (44). They tell Mrs. Spencer’s brother Robert, who tells his daughter Nancy, who tells Mrs. Spencer, who tells the asylum, and this extensive chain of orality results in Anne’s arrival. So even before Anne’s selection from Hopetown, orality draws her to Avonlea. When she arrives, a storied atmosphere already cloaks Green Gables. At the novel’s opening, when Rachel Lynde’s burning curiosity drives her to seek the cause of Matthew’s departure from town in his best suit, Marilla tells Mrs. Lynde the story of their decision to adopt an orphan boy. The story of Mrs. Alexander Spencer and the Hopetown asylum is one of Marilla’s few long speeches in the book, an uninterrupted stint worthy of Anne herself (6-7). Not a silent listener for long, Mrs. Lynde counters with a barrage of orphan stories, tales of all the frightful things that orphans might do to their adoptive families, including “suck the eggs,” put “strychnine in the well,” and “set fire to the house at night” (7). No bearer of sunshine and fairy-flowers, Mrs. Lynde creates the tense context into which Anne will enter, and against which Anne must prove herself as both unfelonous orphan and storyteller.

19 Anne’s establishment as a worthy orphan is, of course, tied to her actions, but it is also clearly tied to her storytelling abilities. Anne has already won Matthew on the Bright River drive, and it is the story of her life before Green Gables that causes Marilla to feel “pity … stirring in her heart for the child” (41). These storytelling acts secure Anne’s place in the Green Gables household. To secure her place in the Avonlea community, Anne must secure the goodwill of its preeminent storyteller: Mrs. Rachel Lynde herself. Though Anne gets off on the wrong foot in this endeavor (and a stomping foot at that), her anger at Mrs. Lynde is nonetheless presented as a performance. Oral storytelling is distinguished from print storytelling, in part, by its distinctive use of voice inflection, sound effect, and bodily enactment of the story’s plot, all aspects seemingly unavailable to the print form (Bauman; Frever, “Woman Writer”). All of these qualities are present and described specifically in Anne’s rebuke to Rachel Lynde, thus recreating Anne’s angry outburst as a significant oral performative event in itself. We are told that Anne “cried in a choked voice, stamping her foot on the floor” and that she faced Mrs. Lynde “undauntedly, head up, eyes blazing, hands clenched, passionate indignation exhaling from her like an atmosphere” (65). Anne is not merely feeling her anger; she is enacting it, performing it, and though sincere and unplanned in her sentiments, this description recreates her outburst as an instance of orality.

20 The sound effects in particular mark Anne’s tirade as an oral performance. We are told that Anne gave “a louder stamp with each assertion,” and to heighten that effect, the omniscient narration interjects a “Stamp! Stamp!” to punctuate Anne’s speech (65). Moreover, when Anne leaves the room, we are told that she “rushed to the hall door, slammed it until the tins on the porch wall outside rattled in sympathy,” and that a “subdued slam above told that the door of the east gable had been shut with equal vehemence” (65). Though Anne is not herself telling a story in this instance, her capabilities as a storyteller are brought to the fore through the narrative emphasis on the performative aspects of her speech. Anne uses pitch, vibration, volume, and quality of voice to convey emotion; she uses eye contact and bodily stance to powerfully move her audience; and she includes a full range of sound effects to heighten the power of her words: stamp, stamp, slam, rattle, slam. But while these aspects are unconscious in Anne’s anger, they become fully conscious and crafted in her apology. We are told that “mournful penitence appeared on every feature” of her face, and that sincerity “breathed in every tone of her voice” (73, 74). Anne is fully, physically rapt in her performance, which is rendered in her own voice, with her distinct spoken vocabulary, and italics to indicate her vocal inflections (73). All of these aspects mark Anne as a storyteller, here presenting herself to an already-established Avonlea storyteller for approval.

21 And Mrs. Lynde provides her approval. She is described as “not being overburdened with perception,” by way of explaining how Anne’s overdramatic performance — sincere though it was — did not offend Mrs. Lynde’s sensibilities (74). One might suspect, however, that as a storyteller herself, Mrs. Lynde may hold some appreciation for the storyteller’s qualities so evident in Anne. Indeed, Mrs. Lynde’s act of forgiveness comes with a gift of story. Mrs. Lynde tells of a girl she knew from school with red hair that changed to a “real handsome auburn” when she became an adult (74). This story not only heals the breach between Mrs. Lynde and Anne, but endeavors to heal Anne’s pain over her red hair itself. Perhaps the tale of the auburn-haired girl achieves its goal, because Anne replies that she “could endure anything if only I thought my hair would be a handsome auburn when I grew up” and later in the novel notes that “people are nice enough to tell me my hair is auburn now,” in an echo of Mrs. Lynde’s forgiveness story (74, 299). In this interaction, Anne-as-storyteller gains the approval of Mrs. Lynde-as-storyteller, and a healing story seals the exchange. Just as the content of Anne’s fairy stories links her to a larger oral tradition, here her performative qualities, and her ability to use story for social purposes in an already-established oral community, tighten her bonds to the larger world of orality. Each of these moments of story-transaction reaffirms Anne’s position as a storyteller in the Avonlea community and, by extension, in the larger world outside the novel.

22 Paula Gunn Allen has argued that in Native American tribal storytelling, stories and storytellers often focus on the issue of establishing a “right relationship” within the community, achieving a balance between individual members of the community, the community itself, and the larger universe (9-10). As such, stories can have a healing capacity, serving to “right” relationships gone awry, and to create mental,emotional, or spiritual readjustments in individuals for the purpose of creating harmony in the community and with the world. Though working within a very different cultural community with distinct cultural values (emphasis on individual action, among others), Anne nonetheless exemplifies certain qualities of the tribal storyteller within her own community. She uses story to heal her rupture with Mrs. Lynde; Mrs. Lynde uses story to acknowledge her forgiveness and to ease Anne’s mind over her red hair. Other theorists note that oral story “puts us in touch with strengths we may have forgotten, with wisdom that has faded or disappeared, and with hopes that have fallen into darkness,” and that story can “awaken the lifegiving and transformative energies that help us through our difficulties” (Mellon 1, 2). As the novel develops, Anne uses her monologues, orations, and tales as verbal explorations of different modes of behavior, to assess a “right” and balanced path, and ultimately to ponder and establish her role within the community. In turn, her life lessons are passed on to the reader through her storytelling, casting her as a community storyteller not only to Avonlea, but to her readership, who are in turn created as her community through this act.

23 As with the monologue/reprimand pattern, Anne’s use of story to find her life path and social role collapses levels of narrative, making the reading audience her listening audience, and her community. Just prior to Anne’s curing Minnie May Barry’s case of the croup, for example, Anne is “conversing” with Matthew, in a near-monologue that features roughly one sentence of Matthew’s input to every full-fledged paragraph of Anne’s discourse. Within this dialogue, Anne tells many small sub-stories, particularly of life at the Avonlea school. We learn particulars of Mr. Phillips’s courting of Prissy Andrews, of Rachel Lynde’s and Gilbert Blythe’s political leanings, of Ruby Gillis’s theories on courtship, of the other Gillis girls’ successful courtships (a tale we are told was passed to Anne from Mrs. Lynde), of Mr. Phillips’s neglect of Miranda Sloane’s education, of Jane Andrews “crying herself sick” over a book, and of Anne’s own troubles in geometry (139-41). Though some of these moments might be classified as news or gossip rather than story, because they lack complete plotlines or apparent themes, the novel has already established that even small incidents in Avonlea life, like Anne’s argument with Rachel Lynde, qualify as “story.” Further, gossip is an important component of orality both in novels and in life, so these elements classify as stories unto themselves (Spacks). Interestingly, Montgomery expressed her own distaste for books that squeeze morality into their stories, like a “pill in a spoonful of jam” (Montgomery, Alpine Path 62). Anne’s stories, rather than posing morals outright, represent Anne’s own verbal maneuvrings in her attempt to suss out the ways of the world which she “can’t understand very well” (140). By sharing her verbal explorations directly with the reader through her voice, Anne offers life lessons from which the reader benefits. Anne shuns the prospect of being a noted flirt in favor of monogamy, expressing a preference for “one [beau] in his right mind”; she, somewhat inadvertently, questions the practice of a male teacher who spends more time courting his students than teaching them, and by extension, criticizes the neglect of women’s education by male educators (a problem rectified in the novel by the arrival of Miss Stacy); she explores the role of women in politics and the merits of different political parties; and discusses the importance of “learning lessons,” both from school and from life (139-40). Anne’s verbal grappling with the ways of the world acts as an instructive story for the young female readers of the novel, encouraging them to weigh the significant social issues Anne weighs — government, education, gender roles — over and above the model of Ruby Gillis who “thinks of nothing but beaus” (207). The moral is not passed down as an edict from on high, however. Anne is presented as mulling these issues over, and so her oral moment encourages young girls to come to their own decisions on important issues by weighing the merits of differing views. While in a more conventional household, a parent might enforce views upon a child, in Anne’s upbringing, she works out her life lessons verbally, with an adult standing by as a guide. This episode suggests to young readers that they should think for themselves, arriving at their own conclusions based on a variety of sources, as Anne does. As such, Anne serves as their community storyteller, instructing the youths of the readership through both the content of her stories, and the example she sets through the telling. Lest there be any doubt as to Anne’s capacities to minister to the youth of the Avonlea and readerly communities, consider the location of this moment in the novel. By the end of the same page, Anne is saving a young girl’s life through her “skill and presence of mind” (143). Here too, it is the telling of her actions to the community doctor, who “never saw anything like the eyes of her when she was explaining the case out,” that ultimately heals the breach between Mrs. Barry and herself (144). Though she is perhaps unwitting of her role, Anne’s stories have healing powers tantamount to the healing powers she demonstrates when she cures the young girl’s croup, and these powers are turned outward beyond the bounds of the novel, as well as toward other members of the Avonlea community. Perhaps this effect hints at another element of the novel’s popularity. Perhaps Anne of Green Gables, too, is a story that heals.

24 Anne has additional gifts as a community storyteller, investing the Avonlea community with imagination and humor. True, her own imagination has yet to learn its boundaries, as comically demonstrated through the Haunted Wood episode. Yet even in instances when her “imagination had run away with her” (165), Anne wittingly or unwittingly fulfills her role as storyteller in the community, and both Avonlea and the reader are transformed by her storytelling acts. For example, Anne serves to restore the blighted Diana’s imagination with stories about a dryad who wears a rainbow for a scarf, and another who sits “combing her locks with the spring for a mirror” (173). Though Anne’s plea is direct, “Oh, Diana, don’t give up your faith in the dryad!” (173), the effects of her storytelling are more covert. Her stories keep Diana’s imagination alive in a household where it could not otherwise flourish. Later, Diana marvels at Anne’s imagination after hearing the melodramatic tale of Cordelia and Geraldine, and Anne encourages Diana to “cultivate” her own imagination, both for its own sake and to help Diana with her schoolwork (210). From this discussion grows the Story Club, a storytelling group of girls led by Anne, formed with the purpose of developing their collective imaginations. As with the Haunted Wood, Anne’s efforts go comically awry: Ruby Gillis’s stories are filled with “lovemaking,” Diana’s are filled with murders, and Anne’s are so elaborately tragic as to be rendered comic, as Anne tells us in the story-of-the-story-club related verbally to Marilla (210-12). Though her task of developing imaginations appears to have failed, with each girl expressing loosely the world views she held before (Ruby Gillis’s are as obsessed with courtship as Ruby herself, and plain Jane produces “extremely sensible” stories), the story club proves fruitful in other ways (210). Mr. and Mrs. Allan laugh heartily over Anne’s stories, as does Miss Josephine Barry. So where stories are meant to develop the writers’ imaginations, instead they produce laughter in their audience, an effect that indeed does “some good in the world” (211). Unfortunately, Anne herself has yet to recognize the benefits of laughter at this point in her development, finding it “better when people cry” over her work (211). So though her success as a community storyteller who brings wisdom and healing to the community is unwitting, it is nonetheless success.

25 In exchange, Anne receives a healing story from one of her listeners: Mrs. Allan. Anne informs us that Mrs. Allan “said she was a dreadful mischief when she was a girl and was always getting into scrapes. I felt so encouraged when I heard that” (211). Mrs. Allan’s tale of her childhood, like Mrs. Lynde’s tale of the girl who grew to have auburn hair, serve as story-balm for Anne, helping to heal her worries and correct perceived flaws in her character, while simultaneously establishing Anne’s role in the community through the exchange of stories. Clearly, the comfort Anne takes in Mrs. Allan’s flawed childhood is equally available to the reader who delights in Anne’s childhood mishaps, and again the effects of story extend beyond the bounds of the novel. While not privy to the stories of the story club, readers are brought into the storytelling community through Anne’s actions as both subject and storyteller, and the humorous healing gained by Marilla, Matthew, Mr. and Mrs. Allan, and Miss Josephine Barry is equally available to the novel’s readership. This action collapses narrative hierarchies, creating a communality of readership and character, and a conflation of told tale and lived life, through the novel’s use of orality.

26 Anne’s role as a storyteller, and relationship with the content of her stories, is not confined to the bounds of the stories themselves. That is, storyness surrounds Anne, forming her very atmosphere and perspective beyond the discrete act of telling stories. Again, this effect is most clearly visible through Anne’s connection with two storytelling genres: the fairy world, and the community stories in which she participates. Anne’s characterization as an oral storyteller is reinforced by her near-constant interaction with the world of fairy, outside her own tales as well as within them. Fairy tales are among the most notable and prevalent of the world’s oral traditions, crossing a variety of cultures, and informing the belief systems of the narrative audience. When J.M. Barrie tells his reading audience, three years after the publication of Anne of Green Gables, that Tinker Bell “thought she could get well again if children believed in fairies” (179), and instructs his readers, “If you believe … clap your hands; don’t like Tink die” (180), he demonstrates a principle that pervades both Montgomery’s text and his own: the concept that a belief in the fairy-world extends outside the literary practice that portrays it, asking readers to turn to their own world with new eyes as a result of their interaction with fairy narrative. Not coincidentally, both Barrie and Montgomery are working from a Scottish tradition, a tradition that is profoundly oral in form and aesthetic, and for which the world of fairy forms a portion of its content.13 Similarly, the world of fairy forms the content of several of Anne’s stories, but it also pervades the atmosphere surrounding Anne and shades the omniscient narration of the novel, creating Anne not only as a storyteller, but as someone immersed in storyness.

27 Invocations — particularly nature invocations — are a common mechanism for beginning an oral tale, in a wide array of cultural traditions. Though “once upon a time” is perhaps the most recognizable of these, “il était une fois,” “In far bygone days” (Grierson 106), “Now when the child of morning, rosy-fingered Dawn, appeared” (Homer 188), and “in the days of yore and in time and ages long gone before” (A Thousand Nights 1006) all serve to place the listeners in the eternal time-space of story, removed from the linear time of print, and of contemporary life. This invocation practice sets up several of Anne’s escapades in the novel, marking Anne as existing in a storied atmosphere, as both teller and told. In one of the early passages where Anne explores the Green Gables environs, the narration spends three paragraphs in thick nature description highly evocative of the fairy tale genre. We are told that the “bridge led Anne’s dancing feet up over a wooded hill beyond, where perpetual twilight reigned under the straight, thick-growing firs and spruces” (63). Again, Anne is associated with the Pied Piper through her dancing over the hill, as well as possibly referencing “The Red Shoes” and “The Twelve Dancing Princesses” with her light-footed wanderings. Further, the concept of “perpetual twilight” under the trees signals the entry into the fairy tale realm, with its time outside time. The forest is described as glimmering and talking, other qualities commonly associated with fairy stories. Just after this passage, Anne’s own participation in the fairy world is confirmed, because she “talked Matthew and Marilla half-deaf over her discoveries,” passing on her ventures into fairy through storytelling of her own (63). As well, the omniscient narration uses terminology drawn from the fairy world to describe Anne throughout the novel. In her before-school wanderings, Anne looks “as if she were a wild divinity of the shadowy places,” while her consequent tardiness produces an “impish result” (114). Coming home from the Barrys, Anne passes under a “glittering fairy arch” (144). On the drive to her first concert, Anne hears laughter that “seemed like the mirth of wood elves” (152). When Mrs. Allan invites her to tea, Anne comes “dancing up the lane, like a wind-blown sprite” (178). Indeed, Anne even plays a fairy in the school’s first student concert (193). Though Anne’s association with the world of fairy through the omniscient narration is, in part, characterized as an aspect of childhood, it also firmly weds Anne-as-storyteller to the storytelling world.14 She is cast as an ambassador to the fairy world, and when she returns “from her other world with a start and a sigh,” it is her vocation to share that world with others through her stories (239).

28 Whether she is characterized as wood elf, imp, fairy, or sprite, the novel makes it clear that the fairy world is not solely Anne’s creation by surrounding her with a fairy context through the omniscient narration. The invocations of nature and the atemporal world of story, as well as the descriptions of Anne in her surroundings, place Anne within a larger world of fairy tale as its subject, as well as its teller. Her connection to the world of orality is multifold and non-hierarchical, as she moves freely from subject of fairy story to teller of fairy story, from subject of novel to teller of her own stories, and from ambassador to author and back again. Fairy story exists around and outside Anne, creating a metatextually reciprocal relationship between Anne’s stories, Anne’s world, Anne of Green Gables, and the world beyond.

29 But things are not all whispering firs and rainbows in the world of orality, for the community storytelling context that surrounds Anne depicts tales that are not nearly so pretty as fairies wearing rainbow scarves (239). Recall that Rachel Lynde forecasts doom surrounding Anne’s arrival with a series of tales of murderous orphans (7). Far from being an isolated incident, the dismal prophecies of these first stories hang around Anne for the duration of the novel, filtering into the “real life” of the Avonlea community. Mrs. Lynde’s retelling of the orphans who “set fire to the house at night” and placed “strychnine in the well,” as well as the omnipresent danger of death-by-orphan, echo around Anne throughout her development in this first Anne novel (7). Though Marilla seems to dismiss Mrs. Lynde’s words, when she puts Anne to bed on that first night, she makes a point of saying, “I’ll come back in a few minutes for the candle. I daren’t trust you to put it out yourself. You’d likely set the place on fire” (27). Again, when Anne rushes out to save Minnie May Barry, she drops the candle she is carrying down the cellar stairs, and Marilla later “thanked mercy the house hadn’t been set on fire” (141). When Diana and Anne create a system of signalling to each other through the candles in their windows, Marilla gruffs that “you’ll be setting fire to the curtains with your signaling nonsense” (148). Too, when Anne accidentally flavours the cake she bakes for Mrs. Allan with liniment, she laments, “Perhaps she’ll think I tried to poison her. Mrs. Lynde says she knows an orphan girl who tried to poison her benefactor” (176). Though here they terrify rather than console, Mrs. Lynde’s tales demonstrate clearly that stories transform the hearers, and in turn the world around them, and that Anne’s existence is surrounded by the pervasiveness of story. Even her arrival at Sunday school is preceded by “queer stories about Anne,” testifying to the extent that story surrounds Anne’s existence, both figuratively and literally (80). True, in a time period before electricity, a house afire would be a real danger, and so Marilla’s concerns mightn’t stem from Mrs. Lynde’s words. Yet the recurrence of this thread throughout the novel suggests that the content of told tales is not isolated to the tales themselves, but resonates in the world outside. As with the land of fairy, the community story within Anne of Green Gables exists both in inset tale and in the world beyond, suggesting the connectedness of these two realms.

30 Both the delights of fairy and the pain of poisonous pre-pubescents create story contexts in which Anne functions. Through this characterization, Anne is portrayed as both teller of tales, and subject of them (as indeed she is, by being the subject of Anne of Green Gables as well). In turn, this depiction blurs the boundaries between teller and told, and between story life and lived life. If the tales of Mrs. Lynde — purportedly true-life tales to begin with — filter out into the world surrounding Anne, and likewise Anne’s fairy-vision fills the world around her, then the subject of stories is not limited to the stories themselves. The boundary between world and story is an elusive one, an elusiveness that passes into the world outside the reader, through the novel’s use of orality.

31 Storytelling dominates Anne of Green Gables. Anne tells a seemingly endless stream of stories throughout the novel, undeterred by a listener that frequently tells her to “hold her tongue,” in turn emphasizing the sheer pervasiveness of Anne’s voice in the text. This narrative technique establishes the novel as a site of polyvocality, and aligns it with a storytelling world that weaves an intersecting path with the world of print. The content of Anne’s fairy tales confirms her alliance to a larger story tradition outside the text, thus permitting her vocalizations to exceed the bounds of the novel and connect with readers — and intertextual sources — in seeming direct discourse, transcending the narrator who first describes her. The use of invocation surrounding Anne recasts moments of Anne’s existence in the time-outside-time of the fairy story, simultaneously aligning inset narratives, the larger narrative of the novel, and the world beyond the novel with oral tradition, and thus wedding the novel itself to the ever-afterness of the oral tale. Anne is further allied to oral tradition through the function of her stories and her role as community storyteller, tightening community bonds, participating in a lineage of story as passed from one teller to the next, healing and being healed by the profound power of the tale. In addition to her role as teller, Anne is also steeped in storied contexts, both fairy and community. This conflation of Anne-as-subject and Anne-as-teller creates an elusive conception of “life” and “story” whereby stories bleed into lived life, shifting and shaping its boundaries and perceptions, and life becomes inseparable from its conveyance in narrative. This inseparability is literal as well as theoretical. We know from her journals and her account in The Alpine Path that Montgomery’s own experiences in the world of oral storytelling filter into Anne of Green Gables. We know from the work of Catharine Ross that actual readers feel connected to Anne, and form communities around the novel, fulfilling and exceeding the theoretical construction of a listening community through the novel’s oral narrative structure. In short, the use of orality in Anne of Green Gables has both narratological and social implications, implications for our understanding of “Text” and our understanding of readership, and these structural and social implications are inextricably bound together through the novel’s engagement with orality.

32 Anne’s role as a storyteller, telling tales to Avonlea and to her read-ership in a way that transforms their world, while living herself in a world steeped in storyness, encourages the reader to turn to the world outside the novel and view it with storied eyes. The construction of story-within-story-within-story, and story-within-life-within-story-within-life, places the listening reader within Anne’s world and her equally within ours, until tales themselves are the fabric of the world, whispering in the trees and laughing from beyond the shadows. This collapsing of narrative hierarchy pervades all levels of narrative within and outside the novel: Anne’s inset stories told to both Avonlea and reader, stories about Anne conveyed within the novel and to its readership, and the stories from and about Anne that we hear through the text of Anne of Green Gables itself. Montgomery layers story world upon story world — fairy, myth, community, Anne-story, novel — to demonstrate that the world itself is layered in narrative. That is, the world is made up of narrative layers, and the world is layered into narrative, each flowing back into the other without boundary. This metatextuality serves to bind the reader to Anne of Green Gables as a listening audience to its healing story. Life, story, and novel intersect and interweave through the figure of Anne Shirley, storyteller.

WORKS CITED

Allen, Paula Gunn. Introduction. Spider Woman’s Granddaughters: Traditional Tales and Contemporary Writing by Native American Women. New York: Ballantine, 1989.

Andersen, Hans Christian. “The Red Shoes.” Andersen’s Fairy Tales. Trans. Pat Shaw Iversen. Signet Classics Edition. London: Penguin, 1987. 189-97.

—. “The Rose Elf.” Andersen’s Fairy Tales. Trans. Pat Shaw Iversen. Signet Classics Edition. London: Penguin, 1987. 103-109.

—. “Thumbelina.” Hans Andersen’s Fairy Tales. Trans. Naomi Lewis. Puffin Classics Edition. London: Penguin, 1994. 14-31.

Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin. The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures. London: Routledge, 1989.

Bakhtin, M.M. The Dialogic Imagination. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: U of Texas P, 1981.

Barrie, J.M. Peter Pan. 1911. Puffin Classics Edition. London: Penguin, 1994.

Bauman, Richard. Verbal Art as Performance. Prospect Heights: Waveland, 1977.

The Book of a Thousand Nights and a Night: A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments. Trans. Richard F. Burton. Limited Editions Club Reprint. New York: Heritage, 1962.

Cixous, Hélene. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Rpt. in New French Feminisms. Ed. Elaine Marks and Isabelle de Courtivron. New York: Shocken, 1981. 245-64.

Classen, Constance. “Is Anne of Green Gables an American Import?” CCL: Canadian Children’s Literature/Littérature canadienne pour la jeunesse 55 (1989): 42-50.

Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Corrected Edition. Trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1998.

Emmerson, George S. “The Gaelic Tradition in Canadian Culture.” The Scottish Tradition in Canada. Ed. W. Stanford Reid. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1988. 232-47.

Epperly, Elizabeth Rollins. The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1992.

Fowke, Edith. “A Note on Montgomery’s Use of a ‘Contemporary Legend’ in Emily Climbs.” Harvesting Thistles: The Textual Garden of L.M. Montgomery. Guelph: Canadian Children’s P, 1994. 89-92.

Frever, Trinna S. “Adaptive Interplay: L.M. Montgomery, William Shakespeare, and Virginia Woolf’s Shakespearean Sister.” Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project. May 2004. <http://www.canadianshakespeares.com/essays.cfm>

—. “The Woman Writer and the Spoken Word: Gender, Print, Orality, and Selected Turn-of-the-Century American Women’s Literature.” Doctoral Dissertation. Michigan State U, 1998.

Grierson, Elizabeth. “Assipattle and the Mester Stoorworm.” Scottish Folk and Fairy Tales. Ed. Gordon Jarvie. Penguin Popular Classics Edition. London: Penguin, 1992. 106-22.

Homer. The Odyssey. Great Books of the Western World. Trans. Samuel Butler. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1952.

MacLulich, T.D. “L.M. Montgomery and the Literary Heroine: Jo, Rebecca, Anne, and Emily.” CCL: Canadian Children’s Literature 37 (1985): 5-17.

Mellon, Nancy. Storytelling & the Art of Imagination. Rockport: Element, 1992.

Montgomery, L.M. The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career. 1917. Markham: Fitzhenry & Whiteshide, 1999.

—. Anne of Green Gables. 1908. Bantam Classics Edition. New York: Bantam Books, 1987.

—. The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery: Volume I: 1889-1910. Ed. Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1985.

Norman, Marsha. ’Night, Mother. New York: Hill and Wang, 1983.

Ong, Walter. Orality & Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. 1982. London: Routledge, 1995.

Ross, Catherine. “Readers Reading L.M. Montgomery.” Harvesting Thistles: The Textual Garden of L.M. Montgomery. Guelph: Canadian Children’s P, 1994. 23-35.

Rubio, Jennie. “’Strewn with Dead Bodies’: Women and Gossip in Anne of Ingleside.” Harvesting Thistles: The Textual Garden of L.M. Montgomery. Guelph: Canadian Children’s P, 1994. 167-177.

Rubio, Mary Henley, ed. Harvesting Thistles: The Textual Garden of L.M. Montgomery. Guelph: Canadian Children’s P, 1994.

Spacks, Patricia Meyers. Gossip. Chicago: U of Chicago P: 1986.

Waterston, Elizabeth. “The Lowland Tradition in Canadian Literature.” The Scottish Tradition in Canada. Ed. W. Stanford Reid. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1988. 203-231.

Waterston, Elizabeth, and Mary Rubio. Afterword. Anne of Green Gables. By L.M. Montgomery. Signet Classics Edition. New York: Penguin, 1987.

Wilmshurst, Rea. “L.M. Montgomery’s Use of Quotations and Allusions in the ‘Anne’ Books.” CCL: Canadian Children’s Literature 56 (1989): 15-45.

NOTES