Articles

A Legacy of Canadian Cultural Tradition and the Small Press:

The Case of Talonbooks

Kathleen ScherfUniversity of Calgary

1 NINETEEN SIXTY-SEVEN was an auspicious year for the support and profile of Canadian literary culture. The Centennial, Expo ’67, accessible Canada Council grants to publishers and authors, Local Initiatives Project and Opportunities for Youth grants, the expansion of universities and their student bases, and the tenth anniversary of McClelland & Stewart’s launch in 1957 of the New Canadian Library series — all played a role in raising the Canadian literary consciousness. Two of the consciousnesses raised belonged to David Robinson and Jim Brown, who in that year launched on the University of British Columbia (UBC) campus a little magazine called Talon.

2 The expansion in literary culture of which Talon was a part included the breathtakingly rapid expansion of little magazines and small presses in English Canada during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1967, for example, Canadian Literature devoted an entire issue (number 33) to “Publishing in Canada.” The issue contains responses to a questionnaire about Canadian publishing circulated by editor George Woodcock to various writers and publishers: Earle Birney, Kildare Dobbs, Arnold Edinborough, Robert Fulford, Roderick Haig-Brown, Carl F. Klinck, Hugh MacLennan and Robert Weaver — all big names. Not one of those questions or answers deals with the existence of small presses, and of the issue’s six additional articles about publishing, only one, by Wynne Francis, has as its subject “The Little Press,” and it is primarily a checklist.

3 Only three years later, in 1970, in a Dalhousie Review article on Canadian poetry published in 1969, Douglas Barbour remarks that eighteen of the twenty books under consideration in his review were issued by small presses. Three years after that, in 1973, Woodcock devoted another issue of Canadian Literature (number 57) to the Canadian publishing scene. By now, the impact of 1967 and its attendant cultural nationalism were evident, even in the issue’s title. 1967’s descriptive title “Publishing in Canada” becomes wholly prescriptive in 1973, when the title urges us to “Publish Canadian” — all that’s missing is the exclamation mark. Of the nine articles on publishing, five focus on small presses, and this time the respondents to Woodcock’s questionnaire are all associated with “the new wave in publishing”: Shirley Gibson (Anansi), Michael Macklem (Oberon), Dennis Lee (Anansi), David Robinson (Talonbooks), James Lorimer (James, Lewis & Samuel), Victor Coleman (Coach House) and Mel Hurtig (M.G. Hurtig).

4 With vigorous activity from Talonbooks, New Star, blewointment, Very Stone House, Klanak, Periwinkle, Sono Nis and others, the small presses of British Columbia were at the forefront of this movement. Considering how geographically and financially marginal the BC small literary presses were, it is noteworthy that a fair number have survived to this day as Active Members of the Association of Book Publishers of British Columbia (ABPBC). According to the ABPBC’s current website statistics, the most editorially and financially active of the surviving small literary presses is Talonbooks.

5 Talonbooks’s primary significance lies in its activity as a publisher of Canadian literature; but as a phenomenon and as a cultural institution, the existence and survival of Talonbooks — and its huge archive housed at Simon Fraser University—is of great scholarly interest, because the life of Talonbooks closely documents and reflects the life of Canadian literary culture since 1967, with a west coast twist. Highlighted since the closure of the venerable Coach House Press is the unfortunate fact that there are only a few remaining living repositories of Canada’s literary cultural history: one is Talonbooks. As the generation of owner-managers who wrote this chapter of Canadian cultural history move toward retirement, and as more of the few remaining small literary presses face evaporation, it becomes increasingly important to document their stories in order to highlight their significance and impact on the larger development of anglo-Canadian culture.

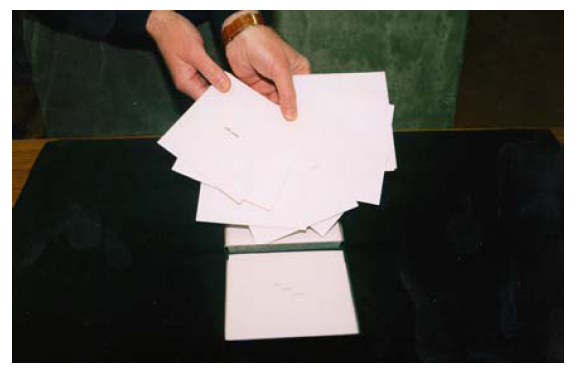

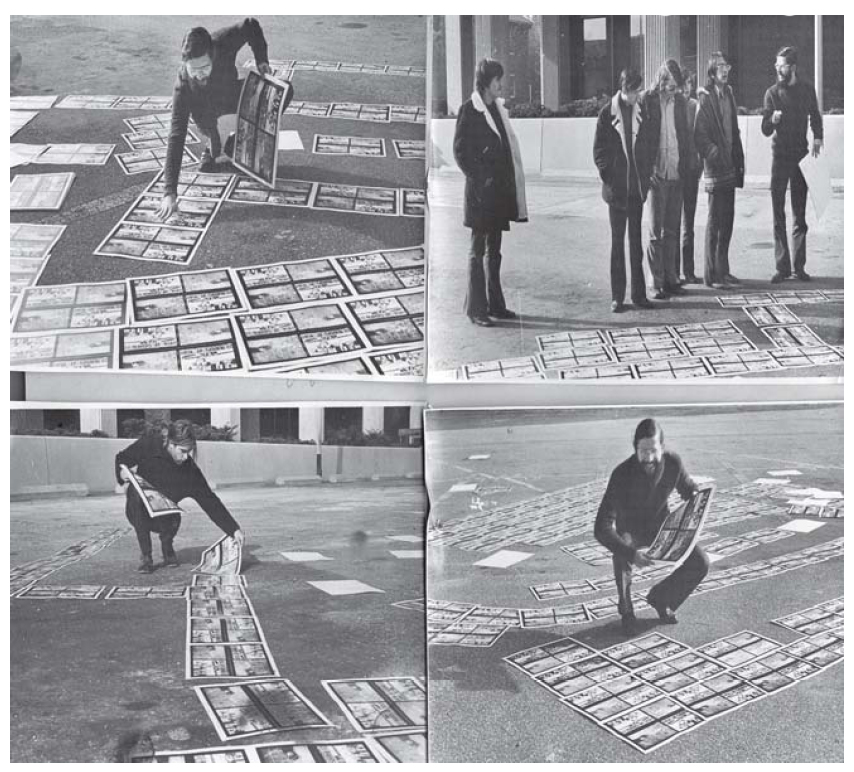

6 In 1967, Jim Brown and David Robinson, two UBC undergraduates, decided to convert Talon, their little magazine, into Talonbooks, a small poetry press. In a recent interview, David Robinson ascribed part of the reason for Talonbooks’s conception to feeling very much part of a local intellectual and artistic movement that included the Vancouver Art Gallery and Intermedia, a movement that provided “enormous support, that was confident of endless possibility, and that luxuriated in experimentation” (Interview). According to Jim Brown, there wasa struggle here on the west coast, because there was a tendency to want to produce the kind of poems that would be successful back east, and that McClelland and Stewart would publish in a book of your poetry. The reason I think that Talonbooks and Very Stone House and blewointment press in particular are important, is that they were … none of those things. (McKinnon 108)From the start, Talonbooks takes an editorial position of difference, of separating itself from and publishing against the geographical and perceived intellectual centre of Canadian letters, raging against that centre, calling out from the rim — an especially gutsy position during the great wave of pan-Canadian nationalism that crested with Expo. According to David Robinson, “Talonbooks’ impetus to begin publishing was local, which is where I think it should be. Canada is such a fucking huge country, you can’t possibly really know who’s writing in the Maritimes” (“New Wave” 57). Situating itself in the local defined Talonbooks even within the UBC campus.

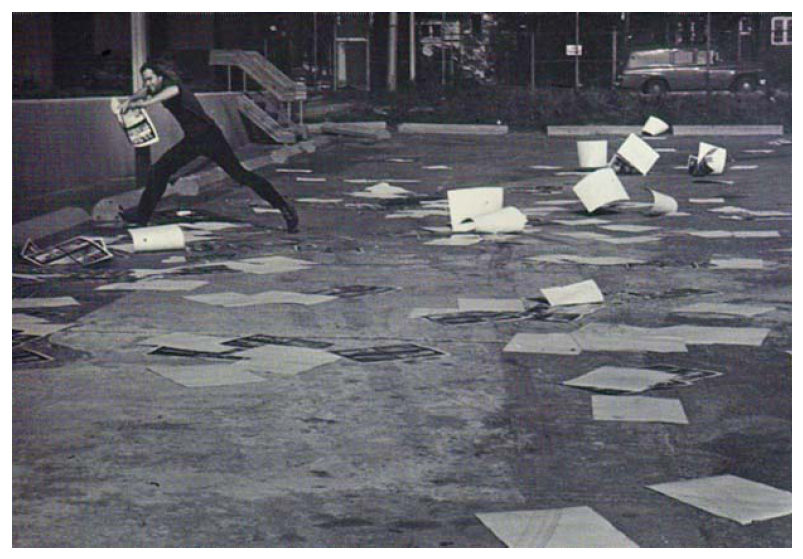

7 Here is Jim Brown in conversation with Barry McKinnon:JB: There was another polarity between the creative writing department at UBC … I guess you could call them classicists or something like that — particularly J. Michael Yates [founder of Sono Nis Press] who was a very strong poet; he had his own dogma.

BM: Part of it was: don’t pay much attention to the local.

JB: Yes, that was the thing.… In the hands of that group of people in the creative writing department, it [the magazine Prism] became obsessed with translation and with writing of poetry that seemed like it was written anywhere else but North America…. Not local; as long as it was not local then you could get published in that.

(McKinnon 109-10)

Talonbooks sought not only to express but also to serve the local. David Robinson’s belief “that we have the writers — poets, playwrights, novelists, short story writers, even artists and film makers, … [who] need books — as a service to their community and to the community at large” (“New Wave” 50) became one of the early strengths of Talonbooks, as this 1972 quotation from Alvin Balkind, then Director of UBC’s Fine Arts Gallery, demonstrates:What Talonbooks … represents is a viable alternative to the present order of printers and publishers. As a press, it has deliberately stepped outside of a profit-oriented situation and has placed its sole emphasis on service to the literary and artistic community.Although the press has seldom worked with more than two or three people, it has made a significant contribution to the arts and letters of this country and to the west coast in particular, where there is virtually no activity with the same degree of sophistication and the same commitment to cultural production. (Talonbooks Archive, MsC 8.1.2.2)Alert readers will of course recognize Balkind’s discourse as supporting a Talonbooks grant application; the founders of Talonbooks believed that the small presses of British Columbia suffered inequities in grant distribution, losing out to the east, beneficiary of most grant money, and to commercial houses, which could show more activity, thus qualifying for larger grants. In a joint letter to the Canada Council dated 7 October 1967, Brown and Robinson state their position:We feel that small press publishers are essential to Canadian Poetry. The publishing of West Coast poets has been sadly neglected. The combined aim of Very Stone House and Talonbooks is to provide a means of repairing this situation. Large publishing firms are neither equipped to handle small editions by new poets, nor are they able to keep pace with current trends — publication through a large press takes years — through a small press, months…. The West needs a voice of its own. This voice must be situated here. (MsC 8.4.5.8)Talonbooks’s specific political position on grants to publishers expresses the geoliterary protest established by TISH earlier in the decade, and which by 1967 was less radical and more widespread. In 1972, Vancouver’s Bob Amussen and Gerry Gilbert issue the first number of their magazine The British Columbia Monthly, whose political and cultural position, announced in the inaugural editorial, manifests thematic similarities to those of TISH and Talonbooks:Sometime last summer George Bowering said that what was needed was a Vancouver Review of Books. From that not-so-chance remark developed the notion of a magazine which would provide an authentic west coast response to new books, films, video, art happenings, food, along with special features on various aspects of life and politics.…We have recycled the title from an earlier periodical… [which] was awash with exhortations… [like] “Educate Eastern Canada.

Pass on the BC Monthly!” Plus ca change…. (1.1 [June-July 1972]: 3-4)

8 One reason the new wave in publishing affected Canadian literary culture so profoundly might be the power it attained from controlling its own means of production. Writers were able to convey their visions not only through their work, but also through their artefacts; they took ownership and therefore assumed responsibility in the act of cultural production. An early Talonbook, bpNichol’s Still Water (1970), is a good example, having won both the Governor-General’s Award for poetry and a Book Society of Canada “Look of Books” design award — a deep and effective penetration of Canadian literary culture.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

9 The “cover” is a 13.5 cm square cardboard box, 1 cm in height, with black edging and a silver mylar cover, lettered with small, unobtrusive black type. The mylar cover reflects as still water would; the “pages” take us down into the pool: they are twenty-eight unattached leafs of white tweed weave card stock containing the concrete poems. The artefact reflects exactly Nichol’s physical vision of Still Water as described in an October 1970 telegram to David Robinson (MsC 8.3. 14.3). Indeed, correspondence from most of the press’s early writers reveals both the extent of their participation in book design, as well as how much Talonbooks strove to include the authors in the physical production of their own works. Take, for example, Victor Coleman’s idea for the cover of his 1972 Talon book Parking Lots, the covers for which were printed at Coach House and shipped to Talonbooks, where the book was assembled. It also won a “Look of Books” award:The cover… is a photo of a mini-minor (Moriss) in an empty Parking Lot with me standing beside it, door open, I’m looking up, pic taken from five stories up. When we get the covers printed we’ll take ’em to the same parking lot on Sunday morning and proceed to try to get a good clear tire print over each of the covers…. That whole event will be documented & photos taken that Sunday morning will be used as the “illustrations” for the poems…. (MsC 8.2.5.19)

10 These photos reveal something interesting about the publishing philosophy at Talonbooks. They document the making of the object; their very existence and their inclusion in the text signifies the importance of the process of cultural production. The leaping man in the next photo is very much like a passage near the end of Daphne Marlatt’s “musing with mothertongue” in her Touch to My Tongue: “inside language she leaps for joy, shoving out walls of taboo and propriety, kicking syntax” (48-49). Like the image of Marlatt’s woman writer who leaps for joy with her new-found linguistic freedom, this image is striking in the joyful leap that kicks out the walls of publishing propriety: the writer can control the means of production of his or her own artefact. Or, as Victor Coleman himself recently reminisced about Coach House Press: “This was how to get those slacker poets into the mix. Allow them to get their hands dirty by helping to make their own books; a way to complete their collective vision of the new direction in Canadian writing and publishing” (28). This sense of collective vision is a defining feature of Talonbooks and of the new alternative presses blossoming across Canada during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

11 These three interrelated features characterize the early period of Talonbooks, a period which runs from 1967 to about 1977: 1) providing an editorial alternative to larger houses; 2) responding to the pan-Canadian, New Canadian Library, patriotic agenda in favour of articulating the local; 3) designing visually arresting books, in which the authors have a hand.

12 Being alternative, local and artist-run are themes which are not, of course, particularly unique to Talonbooks — they are principles any combination of which were shared by the small presses established during this period: Oberon, New Press, Anansi, Coach House. Karl Siegler characterizes this decade as “conscious, co-operative, revolutionary innovation” (“Brief” 12). But the first serious identity crisis for Talonbooks occurred during the mid-1970s, as these presses became established business enterprises.

13 One of the critical challenges evident at this time was authorial dissatisfaction with some of the principles and practices of Talonbooks, whose ideal of a vision shared by writer and publisher was beginning to erode in some cases. For example, during its first decade, Talonbooks was very willing to experiment with alternative form. We have already examined Still Water and Parking Lots; to that we could add the joint publications of written word and phonographic poetry, such as bissett’s awake in the red desert (1968) and Jim Brown’s o see can you say (1969). Drawings, collages, etchings, and photographs were regularly included in Talon books. An outstanding example is Steveston, Daphne Marlatt’s 1974 collaboration with photographer Robert Minden. A survey of the uses of colour in Talon books during the early 1970s is almost psychedelic: red and blue ink (Bowering’s Two police poems, 1969); green paper with green and orange ink (Davey’s Four Myths for Sam Perry, 1970); blue, black, and pink ink (bissett’s drifting into war, 1971); pink paper, red and grey ink (Rosenberg’s Paris and London, 1971). Perhaps following the model of George Bowering’s 1967 Coach House Press book which took the form of a baseball pennant, the formats of Talon books during the press’s early period were also sometimes very alternative to the standard bookseller’s rack and library processing preferences. But by 1975 the sixties were getting around to ending, and the charms of the alternative world were apparently wearing somewhat thin. On 12 July 1975, George Ryga complained in a letter to David Robinson that he, Ryga,made some suggestions to you during publication which were ignored. I requested a re-cut of format to fit wire racks, from which books of inferior quality move easily. You gave me a song and dance about it being your way to do it in the manner you did it in. (MsC 8.4.7.21)Robinson gamely counters on 22 July that “Talonbooks does not and never has published books to fit wire racks” (MsC 8.4.5.7), but Ryga’s letter announces weariness and frustration with one of the rebellious principles of Talonbooks’s conception. Ryga continues:although I can understand and appreciate your individualistic posture regarding Talon, I am too old to sympathize with it or do anything to fortify your spirit. As a long-time writer, and more recently being associated with bookselling, I can assure you many of your decisions are wrong and costly. If you wish to shoulder these liabilities, and find Sunday-writers who feel the same way, that is your business. But as a professional writer, I am simply not interested in anything but the best exploitation of my work, budgetary and personal consideration not withstanding. (MsC 8.4.7.21)Other authors begin to register complaints about the length of time Talonbooks lavishes on its product. Tones range from Stephen Scobie’s rather baroque November 1973Dear David, A letter for your Querulous Authors file (the one marked “discard.”) I was just wondering (vaguely, quietly) whether, since at the time of our frantic phone calls some months ago, all that seemed to be lacking was the cover, which we supplied, there is any prospect of my being able to give a few copies of Stone Poems as Christmas presents (for 1973, that is)? (MsC 8.4.9.2)to Frank Davey’s more forthright “Like either publish or fuck off & stop screwing up other guys’ work” (MsC 8.2.8.4). The initial groovy vibe between alternative writer and alternative publisher seems to be bumming out, but the complaints worked toward making Talonbooks a less playful or — perhaps better — a more mature press: by 1974 it was very rare for Talonbooks to use either coloured paper or inks, and by 1976 almost all Talonbooks were published in a 13 or 14 cm x 21 or 23 cm format which, incidentally, fits wire book racks — I checked.

14 Along with encountering authorial dissatisfaction and accommodating more standard publishing formats, Talonbooks faced a few other challenges to its founding ethos during the mid-seventies. One of these was the realization that, like large publishing houses, Talonbooks’s survival would depend on a more solid bottom line. According to Michael Hayward’s unpublished 1991 paper “Talonbooks: Publishing from the Margins,”with a staff that had grown up during the sixties, it is not surprising that Talon’s entire decision making process reflected that era. Decisions were made communally, but very little attention was paid to the financial side of the operation. No systematic records of production costs were being kept, and as a result it was difficult to say with any certainty whether Talon was showing a profit or a loss. (15)During Talonbooks’s second decade, literary presses, if they were to continue to publish in what was now an established domestic book market, were forced to become more financially professional, as the complaints of authors were clearly signaling. In response to this new pressure, Talonbooks hired Karl Siegler as business manager in 1974. Siegler set out to analyze and to organize, to balance expenses and revenue for individual titles, and to establish regular administrative procedures for the press and its operating budget. Aside from professionalizing present and future Talonbooks operations, Siegler cleaned up messes that had been made before his arrival, including dealing with those irate authors. Playwright Jackie Crossland, for example, waxed vehement about her financial treatment at the “inefficient” hands of Talonbooks, scolding thatmost reputable publishers are fairly concerned with the legalities surrounding publication and often take care to make sure that contracts are signed by all concerned before a book comes off the press. (MsC 8.2.7.15)Siegler’s reply gives us some sense of what professionalizing Talonbooks involved:First off, let me clarify my position in this whole matter once more. I was hired by Talonbooks on Jan. 4, 1974 as a business manager, to deal with their admitted difficulty in this field in the past, present and future…. I am merely trying to settle this matter of gross negligence and incompetence on behalf of all parties concerned after the fact.His letter closes with what we now recognize as vintage Siegler:I simply cannot tolerate another message as personally insulting as your letter, dated Dec. 14, 1974. If you wish to discuss this matter further with me after you have looked at the figures below and the enclosed contract, please do so in a rational, considered manner. (MsC 8.4.9.13)Siegler brought other changes to the administrative structure and procedures at Talonbooks: staff members were laid off, printing was jobbed out, and newly-appointed commissioned sales reps doubled unit sales in three years in both Canada and the United States (Hayward 6). This professionalizing of Talonbooks’s business practices is a mark of the press’s movement into the domestic publishing establishment, as was its maturing involvement in the politics of the Canadian publishing industry.

15 As we have seen, Jim Brown and David Robinson regarded the establishment of Talonbooks as a political act against the geographical and perceived geoliterary centre, and against the large publishing houses situated there. Siegler sophisticated the politicization of Talonbooks by agitating for change in government policies:I realized way back in 1974 when I joined Talonbooks as business manager that some form of government support was needed if Canadians were going to have their own books, authors and publishers. That’s why I got heavily involved right from the beginning in these publishing associations. In fact, I co-founded two of them — the Literary Press Group (LPG) and the BC Publishers Group (BCPG) — in 1974-75. I saw this as part of my job — ie to make the company as lean and as efficient as possible, and since that was not enough to sustain it, to work on an adequate cultural policy from both the federal and provincial governments, which would allow us to survive. (“Desperation” 125)Whereas Brown and Robinson articulated dissatisfaction but essentially went their own way, Siegler, and hence Talonbooks, dove headlong into political discourse (cf. Kogawa’s Obasan (42): Naomi: “But you can’t fight the whole country” and Aunt Emily: “We are the country.”). Like Aunt Emily, Siegler is a word warrior, and during its second decade he led Talonbooks into the politics of the Canadian publishing industry as a vigorous member, leader, and policy forger of professional publishers’ associations at provincial and federal levels, resisting extant models of cultural policy, pushing the mechanisms of public policy to allow Canadian culture to flourish, and claiming his and other small presses’ right to be involved in the systems that govern them. Since 1967, when the existence of Canadian culture was officially endorsed and promoted, the cultural sector of Canadian society and the various levels of government involved with it have been struggling to determine a cultural policy, wrestling with all aspects of such a policy’s vision, definition, purpose, and financing. With the relatively rapid establishment of a Canadian literary press industry, governments and publishers have sought a fair and functional relationship — and they still are, as the recent Donner and Lazar reports demonstrate. 1 Talonbooks became politically sophisticated and active as its role in this new industry solidified.

16 Another lesson in joining the establishment was learned during the seventies, as Talonbooks discovered another reality of the publishing business: the niche market. Talonbooks was conceived as a poetry press, but that conception was modified in 1969 with the arrival of Peter Hay. A professor of drama in Simon Fraser University’s English Department, dramaturge at the Vancouver Playhouse, and one of the founding members of the Playwright’s Co-op/Playwrights Union of Canada, Hay pitched a drama series to Talonbooks, with himself as editor. His proposal was accepted, and the series was launched with James Reaney’s Colours in the Dark (1969), Beverly Simon’s Crabdance (1972), and most notably George Ryga’s The Ecstasy of Rita Joe (1970), which is still a financial workhorse for the press today. Hay left Talonbooks under rather unpleasant circumstances: after disagreements and a six-year legal battle that cost the press $6100 in lawyer’s fees, Hay formally disengaged himself from Talonbooks in 1986 with a $10,000 settlement. But however contentious his relationship with Talonbooks, Hay’s niche-marketing concept worked beautifully. Starting with regional dramatists like Beverly Simons and George Ryga, the press steadily expanded eastward to publish playwrights like Saskatchewan’s Ken Mitchell, Toronto’s David Freeman, Quebec’s Michel Tremblay in translation, New Brunswick’s Sharon Pollack, and Newfoundland’s Michael Cook. In 1977, Karl Siegler felt secure enough to castigate John Goodwin, Michel Tremblay’s agent, for suggesting that Tremblay might prefer to go with a Toronto publisher. In Siegler’s six-page diatribe, we find this declaration:The point of all this is that these figures ratify what we’ve suspected all along — that when it comes to plays in Canada, we are No. 1; we know our customers and they know us, and if it’s plays you want, whether you’re a theatre person, a bookstore, a library or a college, you look first to Talonbooks, where more often than not, you will be more than satisfied. We are now at the point where we refuse to accept a position at the back of the bus when compared to the “giants of the east.” In our chosen area of expertise, we are Number One, period! (MsC 52.23.7)

17 By 1979, Talonbooks, “the largest publisher of plays in Canada, is going international” (Wachtel 20), with two volumes by Sam Shepard. Ten years later, in 1989, Nigel Hunt’s Quill and Quire article crowns Talonbooks “the country’s pre-eminent play publisher” (10). Certainly, Talonbooks’s backlist of Canadian playwrights is impressive: Clark, Cook, Fennario, Findley, Foon, Freeman, French, Garneau, Gray, Griffiths, Langley, Lill, MacDonald, MacLeod, Mercer, Murrell, Moore, Panych, Pollack, Reaney, Ryga, Salutin, and Tremblay, among many others. Talonbooks’s Modern Canadian Plays (1985, 1986; 2nd ed. 1993), edited by Jerry Wasserman, has been since its publication the country’s leading play anthology for the post-secondary market. A good part of the explanation for Talonbooks’s longevity is the incredible success of its drama line.

18 With a stable of good authors, a solid operational structure, a nationally recognized niche market, a number of significant grants, and a respectable profile, Talonbooks seemed to be holding its own as an established English-Canadian literary press. But as presses like Talon-books became mature, another reality of the Canadian cultural industries emerged.

19 At the beginning of the 1980s, the Department of Communications (DOC) launched a new funding program to supplement the Canada Council block grants to publishers. Unlike the Canada Council grants, which were based on publishers’ deficits, and in line with the mindset of the 1980s, the DOC grants were tied to financial success: the more books you sold, the more cash you got from the DOC. Accordingly, between 1980 and 1985, Talonbooks caused some turbulence in the world of small literary presses by diversifying its list to include books with high-volume sales: cookbooks. Mama Never Cooked Like This (1980), The Umberto Menghi Cookbook (1982), and The Granville Island Market Cookbook (1985) made a significant impact on Talonbooks’s sales revenue. According to Michael Hayward’s calculations, “Susan Mendelson’s cookbook alone increase[d] Talon’s unit sales for 1981 by over 60% from the previous year” (9).

20 Despite Talonbooks’s decision to diversify its titles and its attendant rise in sales, it — like 88% of BC publishers — relied on government grants to publishers to keep the press alive. According to the General Industry Survey of Book Publishing in BC 1982-83 (Talonbooks Business (a) 2.7), three main kinds of publishing grants were available at the beginning of the 1980s: the new DOC grants, based on sales revenue, the Canada Council Block Grants program, based on deficits, and provincial funding in the form of the BC Title Assistance program. In 1983, 76.4% of grants received by BC presses came from the two federal government programs, and 19.7% came from BC grants. The Industry Survey provides a statistical analysis to show a pattern of federal government grants decreasing, while the provincial grants remained steady, so that the total amount of real grant money to BC publishers was actually decreasing during the 1980s. When we examine the grants received by distinct genres of publishers, we find the primarily literary presses such as Talonbooks sustaining a combined decline in their share of grants and in market performance. The average print run for a book of poetry in 1983, for example, was — at 600 — about half of what it was before 1981. To make matters worse, literary publishers like Talonbooks who diversified as a result of the DOC grants were finding that cross-financing titles did not work out quite as profitably as they had hoped — cookbooks and coffee-table books sell more units than poetry books, but cost more to produce, and to achieve these greater sales, more money must be put into promotion. In actual dollars, books of recipes do not subsidize books of poems, even with the DOC grants. And yet these grants must be sought, because although government grants covered only 10.5% of publishing costs in 1982-83, they still made — and make — the difference between year-end loss and year-end break-even. If publishing grants disappeared, of the 44 publishers who reported in this 1982-83 document, only 10 (about 22%) would have survived. Government grants, insufficient as they were and are, were and are absolutely necessary for Talonbooks (and any English-Canadian-owned literary press) to continue business. Even in its maturity, this cultural industry, in a decade that emphasized industry perhaps more than it did culture, resulted not only infederal and provincial governments and program administrators, [who were] frankly a bit weary of the “seniors” of this founding generation of owner-managers not having attained an “adequate level” of self-sufficiency “despite all the help they continued to receive from the public sector” (Siegler, “Brief” 13)but also, sadly, in the disintegration of some publishing houses.

21 Frank Davey’s long article in the Spring 1997 Open Letter details how Coach House Press — Talonbooks’s spiritual sister and mentor — came apart as a result of the same kind of turbulence. That press, like many of its generation, was forced to ask itself: are we market-driven or artistically driven? Who are the people in charge? Are we a financially viable operation? Whose vision does the press articulate? The complex issues raised by these questions during the 1980s were further inflamed at the beginning of the 1990s by a federal government initiative. Frank Davey explains:Small Canadian publishers like Coach House were promised in 1992 large amounts of sales-based 5-year marketing money — in effect a tripling of the previous program — by the federal Department of Heritage and then encouraged by federal loan programs to borrow against the expected grants. Part of this new money was unofficially conceived as compensating for the application of the new GST to books, and partly compensating for the terminating of the postal Book Rate. Overall, the grants were also conceived as balancing the new looser policy on the foreign purchase of Canadian publishers under which unprofitable publishers for which no Canadian buyer could be found, could legally be acquired by foreign buyers. By making most small Canadian publishers ‘profitable,’ the grants would make them ineligible for foreign purchase. The massive surprise cuts to these grant programs in the 1995 federal budget left the publishers trapped in an indebtedness which government itself had lured them into undertaking. (76)The federal government also caught Talonbooks fast in this web. Taking the federal government’s advice, and borrowing $43,000 from the Federal Business Development Bank against the increased grants they had been assured would be coming for the next five years, the press increased its title output by 50%, from twelve to eighteen books, hired another employee, and met David Robinson’s demand for a $50,000 pay-off for his share of the company. By 1995, Siegler’s plan was beginning to work. The upsizing of Talonbooks resulted in a 1993 year-end loss of $51,399; in 1995, the year-end showed only a $2144 loss (although the carry-forward deficit was much higher), and every indication was that this upswing would continue; in 1996, the press could reasonably forecast a year-end profit with a sizable chunk coming off its total debt. Disaster struck in 1995, however, when the federal government announced a 60% cut in the grants. Talonbooks was, as Siegler puts it when discussing 1995, the darkest period in his professional life, “completely fucked” (Interview). Siegler owned a company that was well over $25,000 in the red, with only heavily-reduced grants to look forward to. It was, as they say, time to sink or swim. Coach House sank; Talonbooks swam. But, as Siegler remarked at the October 1997 bill bissett “tribyoot,” the government “made whores for Eleusis of us all, they did.”

22 During late 1995 and early 1996, Karl Siegler was a busy man. He negotiated good terms for bridge financing, and talked Jack Stoddart Jr. into an excellent rental agreement for space at General Distribution’s Burnaby warehouse starting in January 1996; this move alone saved the company $15,000 a year. As well, Talonbooks downsized, reducing its staff from four to two, and dropped from eighteen titles in 1995 to seven in 1996. Capitalizing on his excellent payment record, Siegler renegotiated Talonbooks’s terms with its printer, Hignell Press. In 1996, the year Coach House closed, Talonbooks’s year-end statement was in the black. According to the ABPBC website, Talonbooks no longer accepts unsolicited manuscripts, and as the preface to the 1997 thirtieth anniversary catalogue confidently announced, Talonbooks had restructured itself and avrrived at a clear vision of its place in Canadian literature, a vision it had been striving for since 1967:We’d like to take a moment to have a look forward into our future as well as backward into our past. As many of you know, when the federal government announced its draconian cuts to its publishing program two years ago, we embarked upon the largest restructuring program in Talonbooks’ history.We began by redirecting ourselves to our literary roots. While most of our colleagues scrambled to become more “commercial,” we adamantly continued, even sharpened our editorial search for the finest writing in Canada within our community of discourse: the four genres of poetry, fiction, drama and belles lettres from the anglophone and our many other founding nations in translation.This consolidation and rededication to our roots has left us the largest independent exclusively literary press in Canada. For the first time in four years, we restored profitability to the press in 1996, which we will again achieve in 1997, and in the years to come. (Siegler, Preface)Karl Siegler has continually stated — loudly — that Talonbooks has consistently sought to retain its focus as a press dedicated to “the love of an intellectual life, a life of letters.” He has recommitted his press to the literary life, seeking profitability through higher performance levels in a more sharply defined market. Talonbooks is now owned in equal shares by Karl and Christy Siegler, its sense of vision focussed and clear.

23 Reasonable readers of this Talonbooks story should, by now, be thinking of Talonbooks as a successful enterprise in the Canadian cultural industry sector; after all, I’ve constructed this narrative around the trials and tribulations of the company establishing and building collaboratively — with public money — a solid infrastructure; at this point, readers likely expect a conventional ending for this colourful western narrative — Karl and Christy Siegler should now live happily ever after, publishing high-quality writing at Talonbooks, enjoying the prestige and respect they’ve earned for their life’s work. So why can’t they? Because the proprietors of Talonbooks, and all the other owner-managers whose generation created the phenomenon of small press literary publishing in Canada will be, within the next ten years or so, nearing the end of their working lives. What then? Who will buy their companies? Who will maintain and protect the independent Canadian publishing sector? Who will maintain a forty-year investment of public funds? Who will guard the infrastructure, experience, and cultural tradition painstakingly constructed by the small literary presses I suggest are represented by Talonbooks? Unless some public policy changes are formulated, debated and implemented, the answer is probably no one — at least no one Canadian.

24 Is it important to Canadian culture to maintain Canadian ownership of these small presses? Karl Siegler thinks it is. In his 1999 submission to Sheila Copps, the Minister of Heritage, regarding the Donner and Lazar studies, he suggests taking steps to Canadianize the Canadian book trade (“Brief” 31). As Siegler pointed out in his “modest proposal” at a November 1999 forum on Canadian literary publishing at the University of Calgary, this Canadianization would primarily take fiscal forms, such as creating a federally guaranteed revolving operating capital line of credit for Canadian-owned book publishers, and establishing significant tax benefits and incentives for Canadian investors in any Canadian-owned publishing company.

25 The startling events of 26 June 2000 certainly highlight such concerns. On that day, Avie Bennett, owner of McClelland & Stewart for fourteen years, announced that he would sell 25% of the firm to Random House, and donate the remainder to the University of Toronto. Bennett, facing the succession problem articulated by Karl Siegler, and in an effort to prevent the breaking up of the venerable publishing house, askedWhat better way can there be to safeguard a great Canadian institution, a vital part of Canada’s cultural heritage, than by giving it to the careful stewardship of another great Canadian institution? (“McClelland & Stewart”)Random House, owned by the world’s third-largest media conglomerate, Bertelsmann, will take one-quarter of any profits, with the rest going to the University of Toronto to provide an endowment to support Canadian arts and culture. The university, however, is not required to make good on any losses incurred by McClelland & Stewart, a situation which, as Robert Fulford pointed out the day after the announcement, puts Random Housein a position to provide whatever funds are necessary, in return for a larger share of the ownership. Has Bennett, in his effort to provide a stable future for McClelland & Stewart, pointed it toward eventual absorption by Bertelsmann? (“The future”)A good question. If we believe, along with Robert Fulford, that Canada’s largest literary publisher may be vulnerable to foreign and/or conglomerate ownership, then we should be very concerned for the future of those smaller literary presses, herein represented by Talonbooks, on which we continue to depend to foster Canadian literary talent.

WORKS CITED

Association of Book Publishers of British Columbia website. www.books.bc.ca

Barbour, Douglas. “The Young Poets and the Little Presses, 1969.” Dalhousie Review 50.1 (1970): 112-26.

Canadian Literature 33 (1967). Special issue: “Publishing in Canada.”

Canadian Literature 57 (1973). Special issue: “Publish Canadian.”

Cockburn, Jean, and Mary Schendlinger. “Twenty Years of Talonbooks, A Bibliography 1967-86.” line 7/8 (1986): 136-54.

Cockburn, Jean. The Origins and Development of Talon Books Publishing House. MLSc thesis, U of Alberta, Spring 1978.

Coleman, Victor. “The Coach House Press: The First Decade. An Emotional Memoir.” Open Letter 9.8 (1997): 26-35.

Davey, Frank. “The Beginnings of an End of Coach House Press.” Open Letter 9.8 (1997): 40-77.

Fulford, Robert. “The future of McClelland & Stewart.” 27 June 2000. www.robertfulford.com

General Industry Survey of Book Publishing in BC 1982-83 (Talonbooks Archive, Business (a) 2.7). Special Collections, Simon Fraser Library, Burnaby, British Columbia.

Hayward, Michael. “Talonbooks: Publishing from the Margins.” Unpublished paper for Simon Fraser University course Communications 870, April 1991.

Hunt, Nigel. “Drama-book Publishing: Canadians Play the Field.” Quill and Quire Mar. 1989: 10.

Kogawa, Joy. Obasan. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

“McClelland & Stewart Owner Donates Canadian Publishing House to the University of Toronto.” 26 June 2000. www.mcclelland.com/MandS_donated.html

MacSkimming, Roy. Publishing on the Edge: A Cultural and Economic Study of Book Publishing in British Columbia. Vancouver: ABPBC, 1993.

Marlatt, Daphne. “musing with mothertongue.” Touch to My Tongue. Edmonton: Longspoon, 1984. 45-49.

McIntyre, Lillian. “BC Publishing: A Microcosm of Canadian Publishing.” Canadian Library Journal 33 (1976): 21-25.

McKinnon, Barry. “With Jim Brown: Vancouver Writing Seen in the 60s.” line 7/8 (1986): 94-123.

Melanson, Holly. Literary Presses in Canada, 1975-1985: A Checklist and Bibliography. Halifax: Dalhousie School of Library and Information Studies, 1988.

“New Wave in Publishing.” Canadian Literature 57: 1973.

Robinson, David. “From the Unmysterious West.” Books in Canada July 1971: 13.

—. Interview with Kathleen Scherf. 9 June 1998.

Siegler, Karl. “Desperation Filters Up Through the Positions: Two Letters from the Talonbooks Archive.” line 7/8 (Spring/Fall 1986): 124-35.

—. “Amusements.” Open Letter 9.8 (Spring 1997): 92-98.

—. Interview with Kathleen Scherf. 17 January 1998.

—. “A Brief Economic, Cultural and Historical Context for the 1999 Donner Competitiveness and Lazar Needs Assessment Studies Commissioned by the Department of Canadian Heritage.” Unpublished, Summer 1999.

—, and Christy Siegler. Preface. Talonbooks 30th Anniversary Catalogue, 1997. N.pag.

Talonbooks Archive. Special Collections, Simon Fraser University Library. Burnaby, British Columbia.

Tratt, Grace. Checklist of Canadian Small Presses, English Language. Halifax: Dalhousie School of Library and Information Studies, 1974.

Wachtel, Eleanor. “Downhill All the Way.” Books in Canada April 1979: 20-22.

NOTE