Articles

Anthologies and the Canonization Process:

A Case Study of the English-Canadian Literary Field, 1920-1950

Peggy Kelly1 LITERARY CRITICS’ CONTESTATIONS of the traditional canon have led to discussions, in literary discursive communities, of multiple canons. Among the many canons considered by critics who work in materialist and cultural-studies fields are the traditional canon, the feminist canon, and the curricular or institutional canon. Drawing on American critic Alistair Fowler’s categories of canons, Alan C. Golding discusses three canons related to the literary marketplace: the potential canon constitutes the entire archive of literary production, the accessible canon includes those works which remain in print, and the selective canon is made up of accessible literature that is deemed to be of the highest quality (279). However, as Golding points out, “selection precedes as well as follows the formation of the accessible canon, affecting the form that ‘accessibility’ takes” (279). For instance, publishers, whose decisions are determined by market factors, have a major role in the construction of the accessible canon. In addition, editors of anthologies and literary histories have enormous influence not only on the shape and content of their own projects, but also on the shape and content of the traditional and curricular canons.

2 Canonization is a complex process of construction, a process which articulates with race, ethnicity, class, the popular-literature/literary-writing 2 continuum, institutional power struggles, and gender. As Robert Lecker claims, the traditional canon of Canadian literature has been racialized white and gendered male, and “the canonizers can demonstrate their liberalism by admitting a few token savages” (669). Paul Lauter sees similar exclusionary and segregating practices in the United States (438-439, 445, 451). John Guillory views the canon as a middle-class enterprise because being represented in the canon, and thereby acquiring cultural capital, means little to those who seldom read (38). Frank Davey correctly points to state institutions as important players in the canon-making process (678). For example, the Canada Council funds high art, works which are independent of the marketplace, and refuses to fund organizations such as the Canadian Authors’ Association (CAA) that are perceived to be driven by commercial concerns. Through its control over the administration of federal funds, the Canada Council has the power to perpetuate the view of the CAA as a forum of writers who are attached primarily to the marketplace, that is, at the popular literature end of the popular-literature/literary-writing continuum. Furthermore, educational institutions, in their roles as marketplaces for textbook publishers, have the power to create canons through the development of syllabi. Canadian cultural nationalists of the 1920s, such as the members of the CAA and publishers Lorne Pierce and Hugh Eayrs, were instrumental in the production of historical and literary textbooks based on English-Canadian perspectives. The history of the curricula in which these textbooks appear reveals one of the many processes through which non-canonical works become canonical (Guillory 51).

3 In this paper, I examine the production of English-Canadian poetry anthologies between 1920 and 1950 as another process of canonization, that is, as a process defined by struggles over the evaluation of the potential canon. My choice of the dates 1920-1950 derives from a larger project, a Canadian cultural history in which I examine the negotiations made by Dorothy Livesay and Madge Macbeth in the English-Canadian literary field. Relations between the social, political, and cultural forces of this period are vibrant and volatile. The economic upheaval of the Great Depression, the political turmoil of two world wars, technological and social innovations, waves of high nationalism, and fierce debates within the English-Canadian literary community mark this time period as one of immense importance and change. For instance, the copyright amendments of the 1920s were points of great contention between Canadian cultural producers and Canadian printers, and the nationalist fervour among Canadians of the period motivated a conscious development of the traditional canon. Literature was seen as a means of nation building and of developing national unity. The CAA, a volunteer, non-profit, and nationalist organization, began to publish its members’ poetry in 1925, according to CAA historian, Lyn Harrington (249). Originally formed in 1921 by Stephen Leacock, Pelham Edgar, J.M. Gibbon, and B.K. Sandwell in order to lobby against the copyright law, the CAA instituted Canada Book Week, the Governor-General’s Literary Awards, the Canadian Poetry Magazine, and the Poetry Yearbooks, many of which were organized with a nationalist purpose. In E.J. Hobsbawm’s terms, this period of the twentieth century constitutes a “crucial moment” in the history of Canadian nationalism, because nationalism became a mass movement in Canada at this time (12). 3

4 However unique and fascinating the 1920 to 1950 time period is, it also resembles other historical moments in Canada through its practice of systemic discrimination on the bases of class, race, sex, and ethnicity. These systemic biases affected the choices made by publishers, editors, and curriculum developers. Their politically based decision-making perpetuated the distinctly Anglo-Saxon, white, and masculine traditional canon that had been developing since the arrival of European settler-invaders. Furthermore, definitions of quality in literature depend on the evaluator’s gender, class, race, age, and position in the literary field. If systemic discrimination was a factor in the power relations of Canadian society during this period, the literary archive should contain evidence of the exclusion of writers on the bases of class, race, ethnicity, and sex. To test my hypothesis, and following Carole Gerson’s methodology in “Anthologies and the Canon of Early Canadian Women Writers,” I conducted a survey of forty-eight English-Canadian anthologies published between 1920 and 1950. In this study, I concentrate on the factors of gender and ethnicity. These concentrations are dictated by the research material itself, as will become clear in the discussion that follows. I examine, in detail, four anthologies which include writing by members of ethnic minorities, and I analyze the survey’s results for evidence that female writers were liable to be excluded from publication in an English-Canadian anthology.

5 The eastern-European, Irish, African-American, and Asian diasporas of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries brought waves of immigrants to Canada between 1750 and 1950. 4 Upon arrival, these new Canadians were faced with French and Anglo-Saxon imperialist discourses of assimilation, often couched in patronizing and benevolent terms. For example, J.S. Woodsworth’s 1909 text Strangers Within Our Gates represents the Anglo-Protestant ideology of Christian service to the nation and the British Empire, an imperialist ideology which dominated Canadian public discourse of the early twentieth century. Furthermore, English-Canadian literary discourse of the 1920-1950 period was dominated by anti-feminine evaluations; for instance, “virile” was an adjective frequently used by critics of both sexes to compliment an author’s work. In such a discursive community, the adjective feminine becomes an epithet. The work of William Arthur Deacon, Archibald MacMechan, J.D. Logan, E.K. Brown, and E.J. Pratt, professional writers and critics of the period, attest to their gendered views of the literary field of production.5 In addition, these critics, most of whom were academics, had important material effects on the publication records of both male and female writers. For example, E.J. Pratt held a veto over the publication of Canadian poets who submitted their work to the Macmillan publishing company in the 1930s, a period during which Pratt acted as reader and advisor to Macmillan’s president, Hugh Eayrs. As Gerson explains in “The Canon between the Wars,” the work of Doris Ferne, a member of the female collective that founded the first Contemporary Verse, 6 was rejected by Eayrs because Pratt criticized her manuscript for lack of virility (54). Many other examples of exclusionary practice suggest that female writers of the period faced barriers that male writers did not face. For instance, Dorothy Livesay, a published and active modernist writer of the period, was excluded from New Provinces (1936), the only anthology of modernist poetry to be published during the 1930s.

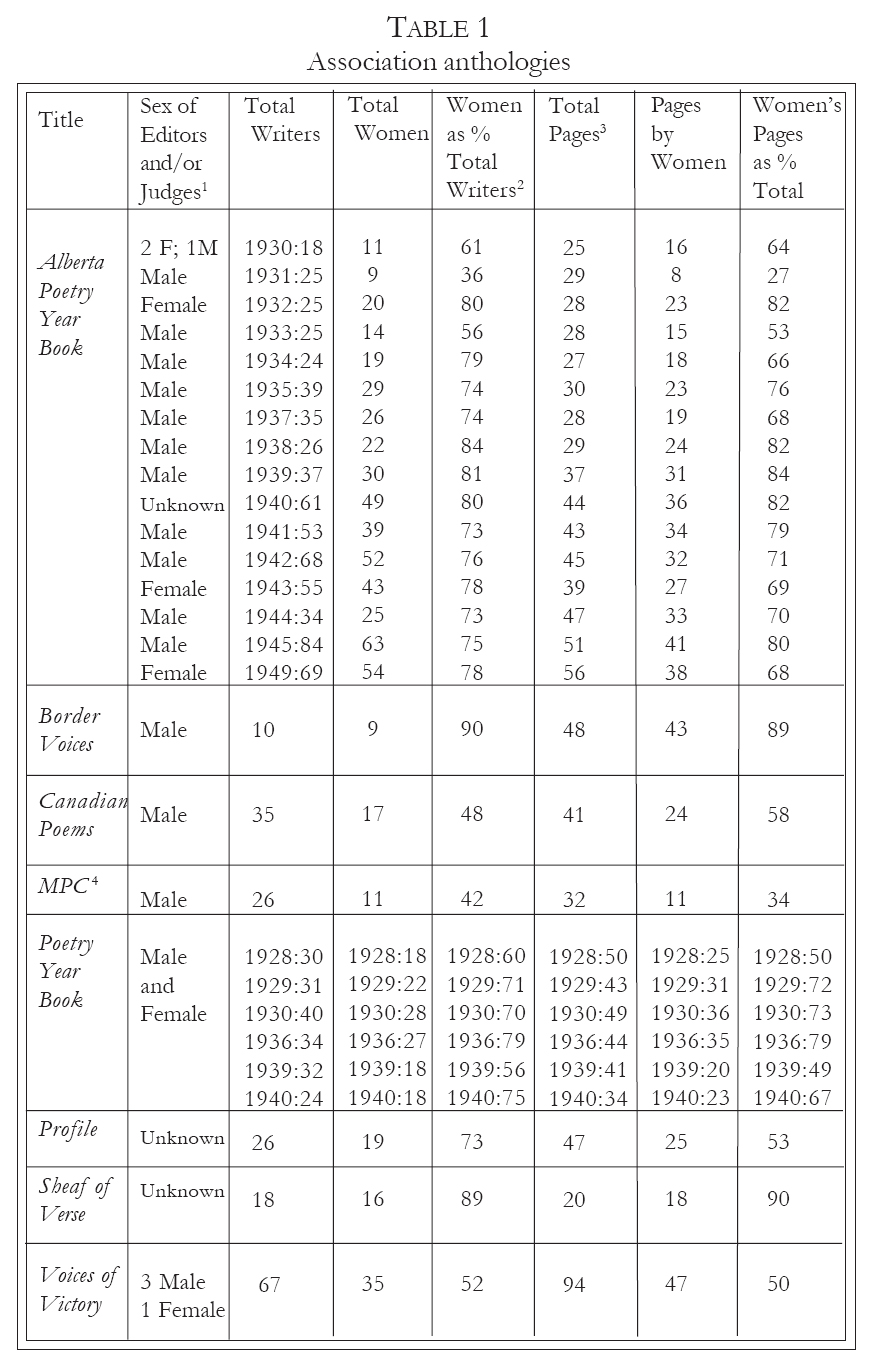

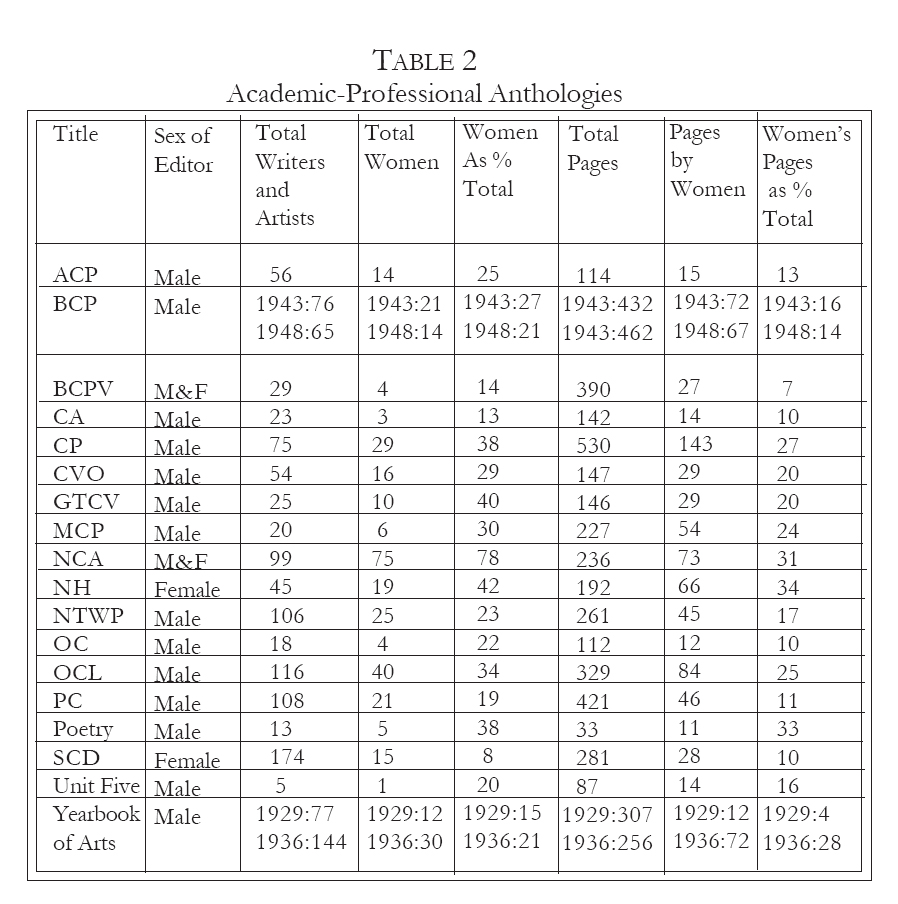

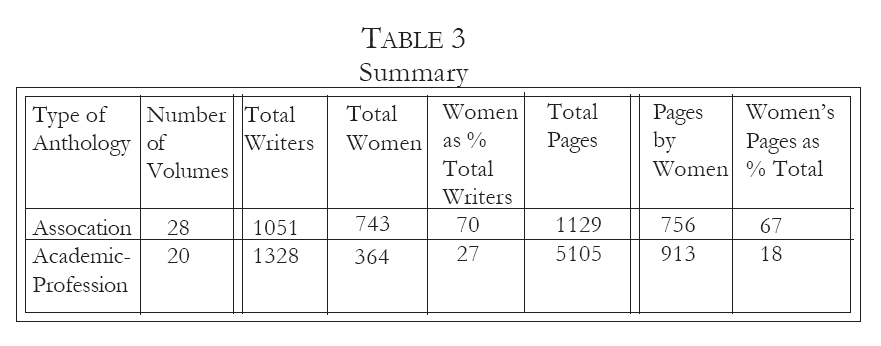

6 I began to compile the database for my study by turning to Reginald Watters’s important A Checklist of Canadian Literature and Background Materials 1628-1960 (1972), which is arranged by genre and alphabetically by author or editor within each genre. Due to the economic collapse of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s, only a small number of anthologies from the 1920-1950 period appear in Watters’s Checklist. Although a few anthologies in my database contain both prose and poetry, I looked mainly for Canadian anthologies of Canadian poetry by Canadian editors. Watters’s Checklist, which represents the potential canon, directed me to both canonical Canadian literary anthologies, such as A.J.M. Smith’s The Book of Canadian Poetry, and to popular literature, such as the anthologies produced by the CAA and the Writers’ Craft Club. 7 The latter publications do not appear in evaluative bibliographies such as Smith’s, which also served as a source for my survey list. The forty-eight anthologies which make up my study fall into two major groups: anthologies produced by individual editors and anthologies produced by associations. The individual editors are mainly academics or professional writers, whose anthologies were produced by established publishing companies; I refer to them as the academic-professional group. The CAA’s and the Writers’ Craft Club’s anthologies make up the association category. My analysis is based on a count of the number of male and female writers in each anthology, as well as the number of pages allotted to each sex. The results of this process appear in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

7 The association anthologies represent a complex position in the field. On the one hand, in comparison to the academic-professional anthologies, which were the products of private negotiations between the publisher and the editor, the association anthologies were produced through a more public and bureaucratic process. Most of the association volumes, twenty-seven of twenty-eight, were published by branches of the CAA. The poems in these volumes were drawn from the results of national or regional poetry competitions held annually by local CAA branches. Two levels of “gate-keepers” operated in this competitive process: the editors and the judges, both of whom made decisions concerning the anthology before it reached the printer (Gerson, “Anthologies” 57). The association anthologies’ editors shaped the anthologies by setting guidelines for submissions and appointing judges, and the judges finalized the anthologies by selecting the contents. Both associations in this survey, the CAA and the Writers’ Craft Club, acted as publishers. In the academic-professional category, on the other hand, the editors both judged and edited the anthologies, and negotiated with the publisher, the second gate-keeper in this category. Although most editors in both groups of anthologies were male, association anthologies were edited by both women and men, whereas the poetry submitted to the association anthologies came overwhelmingly from women writers and was adjudicated by male judges, in most cases. However, in the case of the Alberta Poetry Yearbook, there were only three editors in fifty years, 1930-1980, all of whom were female (Harrington 249-51). During the same period, the judges who chose the contents of the yearbooks were mainly male, according to June Fritch, one of the long term editors of the Alberta Poetry Yearbook (qtd. in Harrington 250). The division of labour for the Alberta CAA’s poetry publications follows the gendered divisions within masculinist systems of power. Judging a poetry contest consisting of hundreds of entries is a difficult task, but it places the judge in a more powerful position than that of editor, a position which involves mundane work. As Fritch comments, “the most devoted woman wearies of this expenditure of her time and talent” (qtd. in Harrington 250). In addition, the volunteer work of the judges is acknowledged in print in the association anthologies, usually in a preface or foreword, but most editors remain unnamed. Border Voices, edited by Carl Eayrs in 1946, and Voices of Victory (1941), a publication of the CAA’s Toronto branch, constitute the two exceptions to this rule. The editorial board of Voices of Victory consisted of three men and one woman and its judges were all male. 8

8 The association volumes garner slight cultural capital, are deemed to be vanity publishing, and have little hope of entering the traditional canon. Almost no critical attention was paid to these publications when they appeared. Only three reviews were published in Canada: two favourable and one unfavourable. For example, in the Canadian Poetry Magazine, an organ of the CAA, Clara Bernhardt praised Voices of Victory as “a collection which every Canadian, for reasons patriotic or aesthetic, will want upon his bookshelf” (44). 9 Voices of Victory was also the subject of the unfavourable review, published a month earlier in Saturday Night and written by Robertson Davies. “It would be dishonest and unfair to the cause of poetry in this land to pretend that this volume is any very significant addition to its literature,” Davies asserted (24). Moreover, F.R. Scott criticized the CAA’s poetry contests for encouraging “old and decrepit” “Canadian poetasters” to write poetry that is ideologically nationalist and imperialist, formally “orthodox,” and humourless (“New Poems for Old II” 338, 337). Both Scott and Davies, unlike Bernhardt, have since become canonical figures in the Canadian literary field.

9 The devaluation of association anthologies is closely connected to the feminization of both popular literature and traditional Victorian stylistics, 10 as well as to Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of the upside-down economic character of the literary field. First, the marginalization and exclusion of feminine, emotional, domestic art forms, and the idealization and centralization of masculine, abstract, public art forms defines such a cultural field; furthermore, the popular end of the continuum is feminized within masculinist ideology. As Andreas Huyssen puts it, “The problem is rather the persistent gendering as feminine of that which is devalued” (53). Second, Bourdieu refers to the economic aspect of literary fields as upside-down because most writers assume that literary writing is above remuneration and non-commercial. Bourdieu claims that even those who object to connections between money and art garner financial benefits in the long run, through the symbolic capital and symbolic power that literary awards bring to an award winner (Field 29-73). In Bourdieu’s model, poetry belongs to the restricted field of literary production, where writers write for each other and literature is not expected to garner financial rewards; however, female authorship, feminine content, and traditional stylistics devalue the poetry published by the associations. As Guillory asserts, “The distinction between serious and popular writing is a condition of canonicity,” one that keeps most women outside the canon, because their work is often labelled popular or frivolous (23). Ironically, editors of some association anthologies hoped to support the production of poetry in Canada by offering prizes of ten to twenty-five dollars and the publication of the winning poems. The monetary prizes were meant to contribute to the professionalization of the literary vocation, and this professionalization was seen to be a necessary step in the development of a national literature. In his Preface to the 1928-29 Poetry Year Book, published by the Montreal Branch of the CAA, Leo Cox mentions the difficulty of “earning a living” and writing at the same time (iii). The CAA’s Ottawa branch also wanted “to provide one more outlet for Canadian writers” by publishing Profile: A Chapbook of Canadian Verse in 1946 (v). However, all poetry publication in Canada of this time period, whether written by men or women, amounted to vanity publishing, including those volumes that were published by established publishing companies, such as Macmillan Canada or Ryerson Press. Therefore, the prizes awarded by some association anthologies carry little weight in the masculinist literary field of the period. Contradictorily, the academic-professional anthologies that were published as textbooks stood to earn profits for their publishers, and the writers included in these textbooks also earned cultural capital by entering the canon through the curriculum. 11 This contradiction in the field rests on a complex foundation marked by gender and artistic generations, and perpetuated through the artificial binary of popular literature versus literary writing and the constructed canon. The mostly female writers who were published in the association anthologies were excluded from more widely distributed, more canonically powerful poetry anthologies. This anti-feminine foundation of the Canadian literary field of 1920-1950 is nicely illustrated by Scott’s comment on the position of modernist poetry in the Canadian literary field of the 1930s:Violent hostility has ceased in educated communities, though in Canada the modernist still has to endure the derision of ageing critics as well as the indifference of the bourgeoisie of poetry readers who pull up their Golden Treasury skirts and pass him by on the other side. (“New Poems for Old I” 297)In this passage, Scott feminizes the bourgeoisie, popular literature, and earlier literary generations at the same time as he masculinizes poets, modernism, and his own literary generation. The implication is that only young, cosmopolitan, upper-class, European-educated, and anticapitalist males like himself are enlightened enough to admit modernist poetry into the literary canon. Scott’s devaluation of non-modernist positions through the tactic of feminization constitutes one of his literary generation’s successful strategies to create a prominent place for itself in the Canadian literary field.

10 When the association and academic-professional groups of anthologies in my study are considered separately, a gender-based dichotomy is clearly evident. The percentage of women writers included in the academic-professional anthologies, twenty-seven percent, is less than half of the corresponding figure for the association anthologies, seventy percent. Furthermore, the amount of space given to women writers in each group of anthologies indicates an even wider discrepancy. Women’s writing fills eighteen percent of academic-professional anthologies and sixty-seven percent of association anthologies (see Table 3). The space assigned to female poets by the association anthologies ranges from twenty-seven to ninety percent of pages, while women’s writing in the academic-professional anthologies occupies from four to thirty-four percent of the total number of pages (see Tables 1 and 2). For example, fourteen percent of the writers published in the academic-professional anthology A Book of Canadian Prose and Verse (BCPV 1923) are female, yet the writing of these four women occupies only seven percent of the text (see Table 2). The much larger amount of textual space allotted to women in association anthologies suggests that when women have control of the material resources necessary for literary production, their published work reflects their numbers, even when positions of power, such as adjudication, are held by men. In the 1943 and 1948 editions of Smith’s canonical Book of Canadian Poetry, women writers constitute from twenty-one to twenty-seven percent of the total number of writers, and Smith allots only fourteen to sixteen percent of the texts’ pages to these writers. Gerson has shown that, after the first edition appeared, Smith gradually eliminated early Canadian women writers from successive editions of the Book of Canadian Poetry, until only two of seven remained (“Anthologies” 61). She also notes, drawing on Anne Dagg’s research, that “In English Canada, from the beginnings to 1950, women have represented 40 per cent of the authors of books of fiction and 37 per cent of the authors of books of poetry” (“Anthologies” 57).

11 Only two of the twenty academic-professional anthologies in my survey are edited by women, while the male editor of a third was assisted by a woman (see Table 2). Ethel Hume Bennett’s anthology, New Harvesting, allocates thirty-four percent of its pages to women writers while Margaret Fairley’s Spirit of Canadian Democracy allots only ten percent, one of the lowest percentages of women authors in the entire group of anthologies. This vast difference may be explained by the nature of each woman’s anthology. Fairley’s is a collection of poems and excerpts from the prose of writers in Canada from 1632 to 1945. Besides the long time-line, Fairley’s collection focusses on politics, a masculine field which excludes most women during the time periods covered in her collection. Furthermore, Fairley draws from a wide range of textual material, including letters, political manifestos, autobiography, fiction, journalism, essays, and poetry, a range that tends to overwhelm genres that have been gendered as feminine, genres such as the novel, the diary, and the memoir. Bennett’s anthology, on the other hand, covers a much shorter time period, 1918-1938, and is restricted to poetry, which is gendered masculine and deemed to be high art, that is, of more value than popular literature because it is supposedly independent of the marketplace. Finally, Alan Creighton, editor of A New Canadian Anthology, lists Hilda M. Ridley, a member of the Toronto branch of the CAA, as his assistant. Among the academic-professional anthologies, this product of a male-female collaboration contains a relatively high proportion of female poets, seventy-five percent. I contend that the lack of women editors among academic-professional anthologies in this survey is evidence of both systemic discrimination on the basis of sex and the power of the symbolic violence of gender, factors that relate to a gendered imbalance of financial and cultural power.

12 Ethnic anthologies, narrowly defined here as anthologies that publish non-English-language writing, hardly appear at all in this group of anthologies. Two association anthologies and two academic-professional anthologies are the exceptions. In the academic-professional category, A Book of Canadian Prose and Verse (1923) contains six untranslated poems by Louis Fréchette, occupying eight pages. Fréchette’s work is followed by a poetic tribute from John Reade, titled “To Louis Fréchette / On the occasion of his poems being crowned by the French Academy” (49). In his poem, Reade describes French- and English-Canadians as “one great race to be,” because both descend from Bretons and Normans (49). In keeping with the nationalist view of the role of literature in nation-building, verse is used by Reade to call for the unity of two ethnicities, based on similarities in genealogical histories. In addition, the poet’s reference to the French Academy gestures simultaneously toward the cultural cringe of colonial writers and to the importance of language as a marker of an ethnic group. Also in the academic-professional category, Bliss Carman’s and Lorne Pierce’s Our Canadian Literature presents an eighty-three-page section of French-Canadian poetry. Sandra Campbell explains that Pierce’s self-proclaimed goal was to unify the French and English sectors of Canada through cultural exchanges; he read French-Canadian litera ture and met the authors during the course of his work as literary editor of Ryerson Press (138-39). Pierce’s rationale for a bilingual edition of a poetry anthology is similar to the assumptions underlying Reade’s poem. Pierce writes, in the foreword to Our Canadian Literature: “The golden age of letters in France and England was born of a common source. In Canada the two traditions again meet, and the roots are buried deep in a common soil” (x). Pierce also encourages other anthologists to create bilingual anthologies: “To speak of Canadian verse without including Canadian poetry written in French is a common fault among us, and one that can no longer be condoned” (x). Writing from “‘La Ferme,’ York Mills,” Pierce belongs, physically and ideologically, to the traditional, centrist view of Canada’s history, that view which recognizes only two founding nations as responsible for Canada’s development (x).

13 Profile: A Chapbook of Canadian Verse (1946) and the Manitoba Poetry Chapbook (MPC 1933) provide the other two examples of attention to ethnicity among the forty-eight anthologies surveyed. Profile was produced by the Ottawa branch of the CAA, and it contains one French-Canadian poem by Marie Sylvia. The Manitoba Poetry Chapbook, on the other hand, is much more extensively an attempt to represent the ethnic diversity among Canadian writers of the period; it includes poems in French, German, Ukrainian, Swedish, and Yiddish. The Manitoba branch of the CAA held a poetry contest that was open to Manitoban poets of all languages. All three of the judges were male, English-Canadian academics, and the winning poems were written in English and Icelandic. In the Preface, Watson Kirkconnell, who also served as a judge of the entries, emphasizes the difficulties of publishing a small volume in several languages and the importance of cooperation to the success of the project. According to Kirkconnell, Winnipeg’s “foreign language presses,” including the publisher, the Israelite Press, worked together to produce the volume (4). Kirkconnell concludes: “The result is a volume quite unique in the history of Canadian poetry. Manitoba is a province of fifty languages, and we hope that this chapbook may convey to other parts of the Dominion some hint of the rich and varied potentialities inherent in this mingling of cultures throughout the years to come” (4). Kirkconnell’s statement contrasts pointedly with Pierce’s assumption of two founding nations in Canada. However, both Kirkconnell and Broadus and Broadus, editors of the Book of Canadian Poetry, assume the existence of an unproblematized mosaic or the desirability of a unified nation. Throughout his academic career, Kirkconnell, a poet and translator, worked towards an acceptance of North- and East-European immigrants by Anglo-Saxon Canadians. His trans-lations of poetry by Icelandic-, Swedish-, Hungarian-, Italian-, Greek-, Ukrainian-, and French-Canadians into English were designed to promote a recognition among English-speaking Canadians of the variety of ethnic cultural groups in the Canadian literary field, a variety that extends far beyond the two founding nations (Craig 598). According to N.F. Dreisziger, Kirkconnell “anticipated the concept of government-supported multicultural programmes by some four decades” (94).

14 In spite of Kirkconnell’s avowed opposition to assimilation, the production of the Manitoba Poetry Chapbook may be used by the state to support its claims that multicultural equality exists in Canada. In such a case, a federal state’s interest in a unified nation is advanced by the work of employees of the postsecondary educational system, as were Kirkconnell and Edmund Broadus. For example, according to Terrence Craig, Kirkconnell wrote Canadians all: a primer of national unity (1940) in order to “reassure Canadians of the loyalty of these immigrants in wartime” (598). 12 Kirkconnell’s major role in the production of the Manitoba Poetry Chapbook must be considered in relation to this project, to which he dedicated himself only seven years later, and which Craig describes in terms that juxtapose a homogeneous group of white Anglo-Saxon Canadians to a homogeneous group of immigrants (598). The slight number of anthologies containing non-English writing in this survey suggests that, although a few members of the English-Canadian field addressed Canada’s ethnic diversity, their efforts were anomalies. Furthermore, the predominance of white Anglo-Canadian writers in this field creates a power imbalance in which non-white, non-Anglo writers function as exotic Others, just as women function as Others in masculinist societies. Such a representation of ethnicity both stems from and perpetuates racialization. At the same time, these anthologies challenge the aspirations to ethnic and racial homogeneity within English-speaking Canada. However, Broadus’s and Broadus’s hope that their anthology will contribute to understanding and unity among Canada’s regions suggests that assumptions concerning the desirability of homogeneity are not far below the surface of their rhetoric (viii).

15 The themes of nationalism and internationalism also intersect with both the association and academic-professional anthologies. Many association anthologies were produced with nationalist aims. For instance, the Alberta Poetry Year Book of 1930/31, one of the few in which the majority of the judges are female, 13 begins with an introduction by Evelyn Gowan Murphy in which she foregrounds nationalism and regionalism:The motive which prompted the Edmonton Branch of the Canadian Authors’ Association to sponsor a poetry competition among the residents of Alberta was a desire to inspire Canadian writers to make use of the vast wealth of western Canadian material which lies before them and to awaken in Canadians, through the medium of verse, a deeper patriotism and interest in their own country. (5)Murphy was disappointed “that the percentage of poems with a distinctive Canadian motif or background were much in the minority” among the submissions (5). The nationalist motivation of these anthologies is grounded in the nineteenth-century notion of the importance of a national literature to a nation’s strength. Moreover, the organization, by a predominantly female association, of national or regional poetry contests around a patriotic theme exemplifies one way in which women fulfill their assigned role of cultural arbiters and conduits. As Anne McClintock points out, nationalist ideology employs the metaphor of the nation as a family to mobilize, in the public sphere, masculinist divisions of labour that already operate within families (357-58). Just as capitalism depends on women to reproduce the worker, nationalist ideology expects women to maintain and reproduce a legacy of cultural traditions which are learned in private and practised in public. The conjunction of nationalism with gendered stereotypes of women as cultural reproducers naturalizes the unpaid production of nationalist poetry yearbooks by voluntary organizations as a feminine activity. The paradoxical corollary to this gendering of literary spaces lies in the delegitimization that feminization entails, a double standard which marks the Canadian literary field as masculinist and undermines the recognition of nationalist cultural products.

16 An extension of this double standard is evident in the fact that nationalist literary productions edited by men are more likely to circulate in the literary field as legitimized school textbooks. A Pocketful of Canada (1946), edited by John D. Robins, professor of literature at the University of Toronto, represents nationalism in the textbook subsection of the academic-professional group. The volume was sponsored by the Canadian Council of Education for Citizenship and the Council’s chair, H.M. Tory, who is also a major figure in Canadian academic history, wrote the introduction. “This ever-increasing accumulation of the written word constitutes the source material from which, after diligent searching, an understanding of the spirit of a nation may be derived,” writes Tory (v). The phrase, “the spirit of a nation” is typical of the Christian bent to public discourse of the period. Although Robins states that “the book is not intended as an anthology,” he does create a textbook which Tory hopes “will appeal to the boys and girls who are in the process of learning to love this land of ours” (xiii, vi). Assimilation of youth is the assurance of a legacy of nationalism, and this textbook furthers a central government’s hopes for the persistence of a federal nationalism. The volume’s black and white photographs, provided by the National Film Board and grouped under captions such as “The Conquest of Space” and “National Events,” exemplify a masculine and centralist construction of Canada. For example, the national events depicted are a hockey game in Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens and a debate in the House of Commons, both almost exclusively masculine fields of endeavour, and both located in Ontario.

17 While nationalist sentiments appear in both association and academic-professional anthologies, internationalism is restricted to the academic-professional group. George Herbert Clarke’s New Treasury of War Poetry (1943) arguably exhibits the most prominent tendency toward internationalism of all the anthologies under discussion. This volume is organized by the names of several countries, all members of the Allied nations, as well as by themes related to war. In the introduction, Clarke states, “This anthology attempts a poetic survey of the objective deeds and experiences of the United Nations and of their subjective defences and advances as well” (xxxiii). Clarke, an academic, treats English as an international language, and the New Treasury of War Poetry functions as propaganda for the Allied cause in World War II. Most poems in this collection glorify war and the soldier’s role, at the same time as they vilify Nazism; thus, democracy and gender stereotypes are both upheld by literary production. In an attempt at homogeneity that was considered essential during the war periods, Clarke describes the poets both as “one in spirit and intention” and “united” (xxxiv).

18 An example of the articulation of internationalism and nationalism appears in Stephen’s The Golden Treasury of Canadian Verse, which Scott so roundly criticized as bourgeois and traditional (1928). In the introduction, Stephen expresses the imperialist nationalism of his historical period and the belief in the importance of literature to the development of “a national spirit and consciousness” (vii). He writes, “If it be true that Canadians are not familiar with the work of the writers who have given to them a national soul and spirit, then it is our immediate duty to correct this defect in our development. Herein lies the reason for the publication of the Golden Treasury of Canadian Verse” (vii). However, Stephen is also proud of the comments of a vettor concerning his successful application of international standards to the anthology (vii). Stephen quotes the vettor’s words, identified only as “a prominent educator,” in his introduction: “The poems, while Canadian in spirit, possess the universal quality of poetry which would be recognised as such by critics outside of our country. I have been a little surprised to find that there is so much good poetry of Canadian origin” (vii-viii). Stephen’s support for international literary standards articulates with colonial imperialism in that he praises Canada for having “carried forward the great traditions of English literature,” and having “produced poets worthy to rank with those who are the glory of Britain” (viii). The Anthology of Canadian Poetry (1942) is also identified with international literary standards. In the preface, the editor, Ralph Gustafson, is critical of the boosterism of Canadian cultural nationalists of the period. “It was forgotten that Canadianism is not necessarily a poem. But that has been outgrown,” he claims (v). In his second anthology, Canadian Accent (1944), Gustafson published Leon Edel’s essay “The Question of Canadian Identity,” in which Edel positions himself against Canadian nationalists. In his foreword, on the other hand, Gustafson describes Edel’s argument as “at certain points inaccurate,” and proclaims the importance of a national literature to the development of national identity (9).

19 My study shows that systemic discrimination on the basis of sex was practised in the English-Canadian literary field in the decades between 1920 and 1950. Not only do the academic-professional anthologies include fewer women, they allow even less space to their women writers than is implied by the male-female ratio of their choices. In addition, the popular-literature/literary-writing dichotomy delegitimizes the literary production of writers who contribute to popular association anthologies and elevates those whose work appears in academic-professional anthologies. Moreover, within this group of English-Canadian anthologies, the ethnicity of Canadian writers is virtually ignored. Finally, these markers of the process of anthologization are perpetuated by the inclusion of academic-professional anthologies in the literary and curricular canons, and the concurrent exclusion of association anthologies. 14 Thus, the production of anthologies impacts on the formation of a canon, in this case by perpetuating the Anglo-Saxon, masculine nature of the traditional, selective English-Canadian canon, which is maintained by the reliance of later anthology editors on the earlier productions (Gerson, “Anthologies” 63).

20 In conclusion, I want to point to the usefulness, especially within educational discursive communities, of analyzing canons. As Lauter states, discussions of canons assist in “reconstructing historical understanding to make it inclusive and explanatory instead of narrowing and arbitrary” (456). Lauter’s point resonates with Catharine Stimpson’s description of the three articulated zones within which canon debates occur:At the first level is the opening up the canon to include works that have been irresponsibly excluded; at the second level is the study of the process of canon formation, for example, the kind John Guillory does; and the third is the questioning of greatness and universals …. all three of those levels have been operating simultaneously. (qtd. in Brooks et al. 387)The literary experiences of the female and ethnic writers whose work was excluded from, or published in, anthologies of the first half of the twentieth century provide instances of the first two steps; the particulars of their experiences deserve further attention from researchers. My survey of forty-eight anthologies provides statistical material for debating the third “level,” “the questioning of greatness and universals,” in one historical moment of the English-Canadian literary field (387).

ANTHOLOGIES INCLUDED IN SURVEY 15

Alberta Poetry Year Book. Edmonton: Canadian Authors’ Association, 1930, 1931, 1932, 1933, 1934, 1935, 1937, 1938, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945, 1949.

Anthology of Canadian Poetry. Ed. Ralph Gustafson. Toronto: Penguin, 1942.

The Book of Canadian Poetry (First and Second Editions). Ed. A.J.M. Smith. Toronto: Gage, 1943, 1948.

A Book of Canadian Prose and Verse. Ed. E.K. and E.H. Broadus. Toronto: Macmillan, 1923.

Border Voices: A Collection of Poems. Ed. Carl Eayrs. Windsor: CAA, 1946.

Canadian Accent: A Collection of Stories and Poems by Contemporary Writers from Canada. Ed. Ralph Gustafson. New York: Penguin, 1944.

Canadian Poems. Calgary: Canadian Authors’ Association, 1937.

Canadian Poets. Ed. John W. Garvin. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1926, 1930.

Canadian Voices and Others: Poems Selected for the Classroom. Ed. A.M. Stephen. Toronto: Dent, 1934.

The Golden Treasury of Canadian Verse. Ed. A.M. Stephen. Toronto: Dent, 1928.

Manitoba Poetry Chapbook. Ed. Watson Kirkconnell. Winnipeg: Israelite P and the Canadian Authors’ Association, 1933.

Modern Canadian Poetry. Ed. Nathaniel A. Benson. Ottawa: Graphic, 1930.

A New Canadian Anthology. Ed. Alan Creighton and Hilda M. Ridley. Toronto: Crucible P, 1938.

New Harvesting: Contemporary Canadian Poetry 1918-1938. Ed. Ethel Hume Bennett. Toronto: Macmillan, 1938.

New Harvesting: Contemporary Canadian Poetry 1918-1938. Ed. Ethel Hume Bennett. Toronto: Macmillan, 1938.

New Provinces: Poems of Several Authors. Eds. F.R. Scott and A.J.M. Smith. Toronto: Macmillan Canada, 1936. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1976. Ed. Michael Gnarowski.

The New Treasury of War Poetry: Poems of the Second World War. Ed. George Herbert Clarke. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries P, 1943.

Other Canadians: An Anthology of the New Poetry in Canada 1940-1946. Ed. John Sutherland. [Montreal: First Statement P, 1947.]

Our Canadian Literature: Representative Verse, English and French. Revised Edition. Ed. Bliss Carman and Lorne Pierce. Toronto: Ryerson P, 1935.

Poetry (Chicago) Canadian Number 58.2 (April 1941) Ed. E.K. Brown.

A Pocketful of Canada. Ed. John D. Robins. Toronto: Collins, 1946.

Poetry Year Book. Montreal: Canadian Authors’ Association, 1928, 1929, 1930, 1936, 1939, 1940.

Profile: A Chapbook of Canadian Verse. Ottawa: Canadian Authors’ Association, 1946.

A Sheaf of Verse. Ed. The Writers’ Craft Club. Toronto: Ryerson, 1929.

Spirit of Canadian Democracy: A Collection of Canadian Writings from the Beginnings to the Present Day. Ed. Margaret Fairley. Toronto, Progress, [1945].

Unit of Five. Ed. Ronald Hambleton. Toronto: Ryerson, 1944.

Voices of Victory: Representative Poetry of Canada in War-time. Ed. Canadian Authors’ Association Toronto. Toronto: Macmillan, 1941.

Yearbook of the Arts in Canada 1928-1929, and 1936. Ed. B. Brooker. Toronto: Macmillan, 1929, 1936.

Table 1. Association anthologies.

Table 2. Academic-Professional Anthologies.

Table 3. Summary.

NOTES TO TABLES

- In most anthologies, editors are unidentified and judges are identified. In some anthologies, neither is identified.

- All numbers over .75 have been rounded off to the next highest number.

- The total number of pages were calculated by counting only pages on which poetry appears. Title pages and pages of illustrations have not been included.

- Following are the full titles for abbreviations used in Tables 1 to 3:

- ACP: Anthology of Canadian Poetry

- BCP: Book of Canadian Poetry

- BCPV: Book of Canadian Prose and Verse

- CA: Canadian Accent

- CP: Canadian Poets

- CVO: Canadian Voices and Others

- F: Female

- GTCV: Golden Treasury of Canadian Verse

- M: Male

- MCP: Modern Canadian Poetry

- MPC: Manitoba Poetry Chapbook

- NCA: New Canadian Anthology

- NH: New Harvesting

- NTWP: New Treasury of War Poetry

- OC: Other Canadians

- OCL: Our Canadian Literature

- PC: Pocketful of Canada

- PROFESSION.: Professional

- SCD: Spirit of Canadian Democracy: A Collection of Canadian Writings from the Beginnings to the Present Day

WORKS CITED

Arnason, David. “Canadian Poetry: the Interregnum.” CVII: A Quarterly of Canadian Poetry Criticism 1.1 (1975): 28-32

Bernhardt, Clara. Rev. of Voices of Victory: Representative Poetry of Canada in War-Time. Ed. Canadian Authors’ Association. Canadian Poetry Magazine 6.1 (Dec. 1941): 43-44.

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Ed. Randal Johnson. New York: Columbia UP, 1993.

Brooks, Cleanth, Gertrude Himmelfarb, Wilson Moses, and Lionel Abel. “Remaking of the Canon.” Partisan Review 58.2 (1991): 50-387.

Brown, E.K. “Canadian Poetry.” Yearbook of the Arts in Canada 1936. Ed. Bertram Brooker. Toronto: Macmillan, 1936.

Campbell, Sandra. “Nationalism, Morality, and Gender: Lorne Pierce and the Canadian Literary Canon, 1920-60.” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 32.2 (1994): 135-60.

Clarke, George Herbert. “Introduction.” The New Treasury of War Poetry: Poems of the Second World War. Ed. George Herbert Clarke. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries P, 1943. xxxiii.

Cox, Leo. “Preface.” Poetry Year Book. Montreal: Canadian Authors’ Association, 1928-29. iii.

Craig, Terrence. “Watson Kirkconnell.” The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature. Second Edition. Ed. E. Benson, W. Toye. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1997. 597-98.

Davey, Frank. “Canadian Canons.” Critical Inquiry 16 (1990): 672-81.

Davies, Robertson. “The Trumpets Falter In Their Sound.” Rev. of Voices of Victory, ed. Canadian Authors’ Association. Saturday Night 57(22 Nov. 1941): 24.

Dreisziger, N.F. “Watson Kirkconnell and the Cultural Credibility Gap Between Immigrants and the Native-Born in Canada.” Ethnic Canadians: Culture and Education. Ed. Martin L. Kovacs. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, 1978. 87-96.

Gerson, Carole. “Anthologies and the Canon of Early Canadian Women Writers.” Re(Dis)covering Our Foremothers: Nineteenth-Century Canadian Women Writers. Ed. Lorraine McMullen. Ottawa: U of Ottawa P, 1989. 55-76.

—. “The Canon Between the Wars: Field-notes of a Feminist Literary Archaeologist.” Canadian Canons: Essays in Literary Value. Ed. Robert Lecker. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1991. 46-56.

Golding, Alan C. “A History of American Poetry Anthologies.” Canons. Ed. Robert von Hallberg. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1984. 279-307.

Guillory, John. Cultural Capital: The Problem of Literary Canon Formation. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1993.

Gustafson, Ralph. “Preface.” Anthology of Canadian Poetry. Ed. Ralph Gustafson. Toronto: Penguin, 1942. 5.

Harrington, Lyn. Syllables of Recorded Time: The Story of the Canadian Authors Association 1921-1981. Toronto: Simon & Pierre, 1981.

Hobsbawm, E.J. Nations and nationalism since 1780: Programme, myth, reality. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990.

Huyssen, Andreas. After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 1986.

Kirkconnell, Watson. Preface. Manitoba Poetry Chapbook. Ed. Watson Kirkconnell. Winnipeg: Israelite P and the Canadian Authors’ Association, 1933. 4.

Lauter, Paul. “Race and Gender in the Shaping of the American Literary Canon: A Case Study from the Twenties.” Feminist Studies 9.3 (1983): 435-63.

Lecker, Robert. “The Canonization of Canadian Literature: An Inquiry into Value.” Critical Inquiry 16 (1990): 656-71.

McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Murphy, Evelyn Gowan. “The Prize Contests.” Alberta Poetry Year Book. Edmonton: Canadian Authors’ Association, 1930. 5.

Pierce, Lorne. Foreword. Our Canadian Literature. Ed. Bliss Carman and Lorne Pierce. Rev. Ed. Toronto: Ryerson, 1935. ix-x.

Reade, John. “To Louis Frechette.” A Book of Canadian Prose and Verse. Ed. E.K. Broadus and E.H. Broadus. Toronto: Macmillan, 1923. 49.

Scott, F.R. “New Poems for Old I. The Decline of Poesy.” The Canadian Forum 11.128 (1931): 296-98.

—. “New Poems for Old II. The Revival of Poetry.” The Canadian Forum 11.129 (1931): 337-39.

Stephen, A.M. Introduction. The Golden Treasury of Canadian Verse. Ed. A.M. Stephen. Toronto: Dent, 1928. vii-ix.

Tory, H.M. Introduction. A Pocketful of Canada. Ed. John D. Robins. Toronto: Collins, 1946. 5.

Vipond, Mary. “The Nationalist Network: English Canada’s Intellectuals and Artists in the 1920s” Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism 7 (1980): 32-52.

—. “The Canadian Authors’ Association in the 1920s: A Case Study in Cultural Nationalism” Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d’études canadiennes 15.1 (1980): 68-79.

Voices of Victory: Representative Poetry of Canada in War-time. Ed. Canadian Authors’ Association. Toronto: Macmillan, 1941.

Woodsworth, J.S. Strangers Within Our Gates, or Coming Canadians. 1909. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1977.

NOTES