"The Immense Odds Against the Fossil’s Occurrence":

The Poetry of Christopher Dewdney as Materialist Historiography

Geoffrey HlibchukUniversity of Buffalo

1 Of central importance to the poetry of Christopher Dewdney is the historicity of nature, and, chiasmatically, the nature of history. This importance is often overlooked by critics of Dewdney’s work, who tend to bypass the historical dimension of his writing in favour of an atemporal solipsism that is presumed to be central to his writing. Such an approach, which sees his poetry as documenting "the solipsism of consciousness" (Hepburn 32), has the effect of lessening the historical impact of the work and instead emphasizing a "dream of Self" as the centripetal force of Dewdney’s writing. Even the historical thrust of Dewdney’s Natural History series tends to become, in Christian Bök’s words, more a portrayal of "heightened consciousness" ("radiant" 29) than a poetic investigation into the intersections of nature and history. Elsewhere, the complex interplay of nature and history in Dewdney’s poetry is frequently brushed under the carpet to make room for the application of more ahistorical or postmodern theoretical approaches. Thus, we frequently see analogies made between Dewdney’s writing and the atemporal theoretical applications of quantum mechanics, Lacanian psychoanalysis, and neurobiology.1 These approaches have led critics to see his poetry as a site wherein temporality is "thought to occur simultaneously" (Highet 17), effectively neutralizing the complex historical juxtapositions that his texts create. Such tendencies would presumably tell us that history is not a central concern of Dewdney’s work, and, indeed, at present there is currently no major study of the historical dimensions of his poetry. Dewdney himself seems almost to have anticipated this oversight in his poetry, writing in the first volume of his Natural History of Southwestern Ontario that "events occur linearly so densely they are viewed as simultaneous" (Spring 21). But a reader does not do justice to Dewdney’s work if this simultaneity is not untangled.

2 This is not to say that previous critical approaches have failed to provide a rich and useful context in which to understand Dewdney’s work, only that the absence of light shed on its historical aspects seems to constitute something of a lacuna. Nor do I wish to suggest that Dewdney’s poetic work is simply historically linear; rather, what makes his poetry interesting is its temporal reconfiguration of natural-historical images. In Dewdney’s own words, his work gives a voice to "the creatures themselves, speaking from the inviolate fortress of a primaeval history" (Predators 8), and his most intriguing poetry describes these voices of the past somehow projecting themselves into the present day. The lyrical subject in Dewdney’s work, dwelling in a contemporary landscape (as do all lyrical subjects), is effectively threatened and placed under siege by this "primaeval history," which forcefully undermines or else mocks its foundations. Although the critical emphasis on subjectivity and consciousness is partly attributable to Dewdney’s own interest in neurophilosophy, this focus threatens to eclipse Dewdney’s poetry, which attempts to problematize subjectivity via natural history. Hence, rather than upholding a solipsistic position, a main feature of Dewdney’s work appears to be a consciousness radically disrupted by the forces of natural history. Solipsistic, then, would be a misnomer for a poetry that so often disturbs the certainty of autonomous consciousness. As Dewdney writes, "Certain people seem to stand behind one" (Predators 55), thus suggesting a multiplicity dwelling behind the single subject. Not only people, but a variety of threatening phenomena exist in Dewdney’s poetry in a number of different forms, all threatening to disrupt the status quo: tornados ripping through small-town complacency, parasites subtly taking over their hosts, remote-control agents menacing consumers in shopping malls, and, most frequently, reanimated fossils ossifying and transubstantiating the flux of contemporary life. This frequency undoubtedly makes the fossil a crucial component of Dewdney’s work, detailing, as it does, a petrifaction of the lyrical subject in such a way that "inadvertent parts" of its self "will be fossilized" (Recent). It is hence in Dewdney’s poetry that the force of history returns onto the present day with a vengeance.

3 Such a collision between fossil and subject is not merely a poetic flourish in Dewdney’s work, but it indexes a particular ideological tactic. To illuminate this strategy, I rely here on the writings of Walter Benjamin, whose work shares numerous conceptual affinities with Dewdney’s earlier poetry. Though there does not appear to be any direct influence of Benjamin’s work on Dewdney (Benjamin’s specific elucidations of materialist historiography that I rely on here were not published until well after the appearance of Dewdney’s early poetry), the congruencies between their work at the very least can illuminate the ways in which Dewdney employs natural history. At best such a tactic may be able to recast Dewdney’s work as a political force, and thus hopefully remedy another lacuna in his critical legacy: the lack of an explicitly politicized interpretation of his work.

4 Benjamin’s and Dewdney’s work is not as distant as it may seem; affinities between the two are seemingly numerous. Both writers’ work takes place on geographically and temporally identifiable planes that are then transposed onto the present: Benjamin’s on the nineteenth-century Parisian arcades, and Dewdney’s on the southwestern Ontario of the Palaeozoic era. Likewise, both locales are hydraulically submersed; Benjamin’s Paris is a "sunken city, and more submarine than subterranean" (Selected 3: 40), as Dewdney’s Palaeozoic southwestern Ontario (site of the future Paris, Ontario, a prominent city in Dewdney’s work) is covered by an ocean "warm, tropical and shallow" (Palaeozoic). Beyond the superficiality of these historico-geographical similarities, an analogy can be made between the modi operandi of both writers. Dewdney once described his work as an attempt to instigate "the rupture of the present by the past, as if the past, instead of being a passive event, has suddenly ruptured back through time and intruded upon the present" (Heinimann 52). Benjamin’s work provides a parallel; a proper historical approach, he explains, does not "fasten" onto the objects of the past, but rather "springs them loose from the order of succession" (Arcades N10a, 1). The past is not studied, then, as much as it is unexpectedly released. This strategy of blasting objects "out of the continuum of history" (Selected 4: 395) is an activity that Benjamin sees as making us "recognize today’s life, today’s forms, in the life and in the … lost forms" of the past (Arcades N1, 11). Worried that modernity’s desire to distance itself from the past was leading it down the road of fascism, Benjamin attempted to destabilize the present by identifying paradigms of the past that could derail the historical continuum along which the modern travelled. Beyond any epistemological value it may have, the purpose of such a radical historiography is to rescue phenomena "from the discredit and neglect into which they have fallen" (Arcades N9, 4), thus saving them from being paved over by the relentless highway of progress.

5 This restoration of the neglected is the crux of what Benjamin referred to as materialist historiography. In what was to be the realization of this method, The Arcades Project, Benjamin attempted a critique of the prevalent historiography (mostly influenced by Hegel) that saw history as a fatefully progressive drive towards a cumulative and all-encompassing spirit. But where this Hegelian framework sees history as a progressive drive towards the utopian absolute, the materialist historiographer sees only a catastrophic accumulation of death and loss. Since Benjamin recognized that history inevitably sides with the victor, then the materialist historiography allies with the dead and forgotten in order to provide an alternative to the dominant ideology. It attends to those who have been brushed aside by history. Otherwise, "Whoever has emerged victorious participates to this day in the triumphal procession in which current rulers step over those who are lying prostrate" (Selected 4: 391). Progress, for Benjamin, is only the result of a high optical vantage point that comes with unwittingly standing on a growing mass of dead bodies; the job, as he saw it, was to make ourselves more aware of this necrotic substructure. This disavowal of progress is understandable in light of Benjamin’s historical context, which saw him writing his last works on historiography just as the Nazis were reaching their apotheosis. But Benjamin’s attitude is also more generally shared by Modernism, specifically in its privileging of the fragmentary and discontinuous over the holistic and sequential. A fragment no longer retains its force when sewn into a tapestry of continuity; hence the idea of progression is antithetical to Benjamin’s philosophy of the fragmented and the discrete. As he wrote to Max Horkheimer, a work is better composed "the more it will be able to break free from a superficial continuity" (qtd. In Jennings 24). This attitude toward progress significantly problematized his Marxism, much to the consternation of his colleagues in the Frankfurt School, since it prevented him from believing in a history that would progressively culminate in the victory of the proletariat. More than just a criticism of Marxist-Hegelianism, however, his critique of progress was an attempt to shock the world out of its mythological belief that everything was getting better. To combat this erroneous faith in progress, Benjamin has the historian resuscitate the people and objects of a lost and forgotten history and take them out of sequence to recirculate their ghosts in the contemporary era, thus memorializing those whom the dominant ideology would best like to forget. This haunting serves to defrock the guise of progress, and redeem these lost spectres from the continuum of history that would have otherwise banished them to oblivion. In opposition, then, to a history that would present a predictable "eternal image of the past," Benjamin instead calls upon the materialist historiographer to present "a given experience with the past — an experience that is unique" (Selected 3: 262). This experience is typified by a shock-like encounter with memory that "flashes up at a moment of its recognizability" (Selected 4: 390). No longer tending over a smooth progression of time, Benjamin’s historian seeks images that would disturb the complacency in which we dwell. This is also Dewdney’s project, to jostle the snug certainty in which we live. To effect such a shock, Dewdney’s strategy, like Benjamin’s, is to implement the subaltern voices of those who have been violently silenced. As Dewdney describes it, his poetry is an "emphatic statement for all those things that have been trampled or destroyed … by West european industrial nations," a "sort of speaking for those that cannot speak for themselves" (O’Brian 92). These voices are emblematized, in Dewdney’s poetry, in the figure of the fossil. Hence, much of his poetry uses the fossil as a forgotten figure, seemingly distant yet fast encroaching upon the present day:The ravine is submerged in a cedar forest, roots probing rock, searching for pockets of ancient being, lost continents. The cedars tap the Silurian era, they live on the essence of the fossils in the rock freeing something locked into the stone for millions of years. (Radiant 95)This image of the past returning in an unmediated form to the present is typical of Dewdney’s work. He thus shares with Benjamin the strategy of awakening the archaic in order to startle the present out of its complacency, a strategy evidenced in both authors’ employment of the fossil, the archaic emblem par excellence, in their respective works.

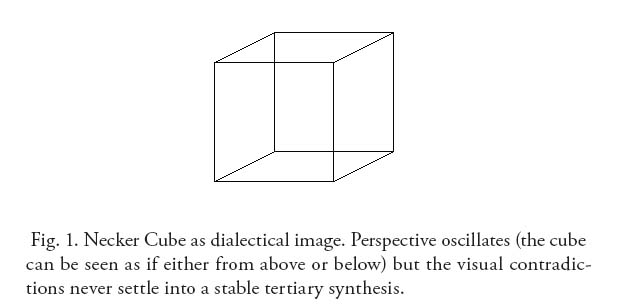

6 For Benjamin, the fossil is emblematic of a "dialectics at a standstill" (Arcades N2a, 3).2 Given its oscillatory status (not only as a simultaneous trace of life and death, but also as exhibiting the dual status of nature and history), the fossil lies in a permanent in-betweenness and, as such, is resistant to dialectical synthesis. If Hegel’s dialectic is concerned with the unfolding of spirit, then the fossil, as employed by Benjamin, represents its bête noir. This is because Benjamin uses the fossil to allegorize the intactness of dialectical contraries prior to their Hegelian synthesis; it reminds us that "nature" and "history" cannot be sublated into a tertiary reality, since the fossil is simultaneously nature and history. Benjamin, concerned that nature and history were being synthesized to the extent that historical ‘progress’ was seen as natural, attempted to separate the terms so that their difference could be preserved. The fossil became something of a symbol of this separation. Hence the two terms comprising "natural history" are separated to the point of their becoming the inverse of the other, so that, according to adorno, the "historically concrete becomes … the archetypal image of nature … and conversely nature becomes the figure of something historical" (Notes 2: 226). Or, to use a metaphor gleaned from Dewdney, we might say that the fossil is a sort of Necker cube, one that exhibits contradictory perspectives without being sublated into a third dimension (see fig. 1). While the fossil indeed may carry a dialectical potential — it can be seen as an historical link in aristotle’s great chain of being — Benjamin and Dewdney do not employ the fossil in order to ground a stable origin of human subjectivity. Their work looks to the antediluvian not to discern our place in the world, but rather to awaken distanced and forgotten phenomena that may jolt or disrupt such a placing. As Rolf Tiedemann explains, Benjamin’s "historical line of vision no longer falls from the present back onto history; instead it travels from history forward" (941). Subsequently, both writers invoke the fossil in an attempt to fossilize the living; hence, akin to history and nature, the fossil and the living are chiasmatically employed. As Dewdney writes, "THE FOSSIL IS PURE MEMORY" (Palaeozoic), and in his work this memory intertwines with subjectivity itself in a sort of reverse anthropocentrism. That is, rather than the lyric poet fossilizing the particulars of the environment into stasis, the poet, in Dewdney’s work, becomes fossilized by these particulars. This is prevalent in "Out of Control: The Quarry," a poem that takes place in a "deserted quarry":You then lean over and pick up a flat piece of layered stone. It is a rough triangle about one foot across. Prying at the stone you find the layers come apart easily in large flat pieces. Pale grey moths are pressed between the layers of stone. Free, they flutter up like pieces of ash caught in a dust-devil. You are splashed by the other children but move not. (Predators 105)Subject and fossil hence perform something of a chiasmus; the fossilized moths trapped in the stone flitter back to life, while the subject itself becomes fossilized. The fossils, then, are returned to temporality, as exemplified by their being swept up in a "dust-devil," while the fossilized subject of the poem becomes caught in atemporality; the deserted quarry seamlessly becomes a populated playground. In this temporal leap, the lyrical subject experiences a sort of fossil-time that marks it off as "other." This poem perhaps comes closest to exemplifying Dewdney’s concerns, and its importance is further attestable by its appearing twice in his collected book of poems, Predators of the Adoration.

Fig. 1. Necker Cube as dialectical image. Perspective oscillates (the cube can be seen as if either from above or below) but the visual contradictions never settle into a stable tertiary synthesis.

Display large image of Figure 1

7 Thus, rather than just a site where history occurs simultaneously, Dewdney’s poetry is more a depiction of the present wherein the past interrupts suddenly and unpredictably. His work features a panoply of animals, both present and prehistoric, roaming across the poems’ locales without cognizance of their anachronisms, "Because they are both out of place & welcome" (Predators 130). Benjamin’s depiction of the nineteenth-century Parisian arcades similarly makes impossible juxtapositions of time; the dinosaur walks alongside the flâneur. These anachronisms, rather than being surreal flourishes, are employed in order to allow history to break through the present moment, to "make the continuum of history explode" (Benjamin, Selected 4: 395). As such, it is somewhat reductive to consider Dewdney’s work synchronic without consideration of this historiographic aspect. To consider his poetry as temporally synchronic would presume a simplistic treatment of present and past in this work. However, the fossil and the human do not simply cohabit within these locales in Dewdney’s poetry. The human subject stands not so much paratactically to the fossil as completely absorbed by it. Consider the following section of Dewdney’s poem "a Phonology of the Coves":This lime-storm is no paradigm only sound eclipsed by its own texture could raise the voltage in these flowers (the current denies prediction) only these leaves could design the ontology of such a sweet storm. The angle of prehistoric imbalance contorts my fish-eye concentration in such a manner that the vantage over this prow steadily weakens the grip of my feet on the ground. (Palaeozoic)Limestone, composed of the sedimentary remains of marine animals, and a key trope of Dewdney’s work, here morphs into "lime-storm." The fossil blends into the geographic landscape itself, which catalyzes the destabilization of the poem’s lyrical subject. The limestone grafts itself onto the climatic backdrop of the poem, allowing for an "angle of prehistoric imbalance," which "weakens the grip of my feet on the ground." "Lime-storm" is a further deviation of "line-storm," a violent thunderstorm typified by a radical demarcation of cloud, thus associating the past, in Dewdney’s catachresis, with a sublime, unpredictable force. Such a connotative aura is amplified when considering Benjamin’s observation that "redemption is the limes of progress" (Selected 4: 404); it is only the redemptive rescuing of the past that can weaken the grip of the feet of progress. The poem thus describes an exceptional force of the past (exceptional since it is not paradigmatic) returning suddenly (as it "denies prediction") and upsetting the stance of the poem’s subject.

8 Though seen in "Phonology" as part of a weather pattern, the fossil cannot be relegated to the background in his work. In a poem entitled "Transubstantiation," Dewdney writes that Devoid of perception the blind form of the fossil exists post-factum. Its movement planetary, tectonic. The flesh of these words disintegrates. (as the words must be placed together in light of theiyr [sic] skeletons. (Palaeozoic)Fossils existing post-factum would be what Dewdney elsewhere refers to as "living fossils," which are also "sacred emissaries of the primaeval" (Predators 7). These are the traces of the distant past literally haunting the present day, oscillating somewhere in the space between life and death. But why does Dewdney animate fossils instead of animals? a fossil is emblematic of an animal without the mediation of death, since its death predates its own existence (otherwise it would not be a fossil). But although normally "devoid of perception," the fossil here is able to roam through a "planetary, tectonic" plane; it has seemingly forgotten its own death, awakening and drifting through space as some sort of petrified flâneur. Though it should not be here, nor less moving about, the fossil still nonetheless has an existence that is "post-factum." The poem also orchestrates a connection between the fossil and language. If emerson declares that "language is fossil poetry" (562) — a process where the exceptional within language becomes ossified and normalized through everyday use — then Dewdney’s living fossil prevents this normalization, since it would exist as the visible material substratum in emerson’s schematic. Words are seen by Dewdney as comprising both flesh and skeleton; though words may disintegrate, a skeletal remainder exists. In his theoretical work, Dewdney conceives of language as "a living fossil whose flesh transubstantiates itself in the wind of dialectic modification" (Alter 81). Awareness of this skeleton is akin to an awareness of the Marxist substructure; as the latter cuts through the fetishization of ideology by locating its economic substructure, so does Dewdney cut through the fetishization of the word. And although Dewdney’s use of the word "dialectic" is linguistic, it is easy to cast these remarks into a Hegelian mould. A fossil, as a trace of the animal’s death, is preserved to allow for the flesh of language, which thereafter obfuscates its own osteology. In Dewdney’s poetry, however, as in Benjamin’s dialectical image, the process is fundamentally altered; the flesh disintegrates, leaving only the memory of the dead animal behind. It is thereby that the procession of progress is halted, and redemption becomes possible.

9 In another poem, titled "Coelacanth," Dewdney writes, The existence of an extinct species is indicative not of the circumstances engendering its uncanny survival, but the point at which our nets coalesced and forced his appearance. This is not the place of departure. The event is invariably prehistoric. (Palaeozoic)The Coelacanth is a four-hundred-million-year-old living fossil — a fish existing outside of its time — which had been presumed extinct until its discovery in 1938. Here, it breaks through a "point" in time to force two different eras into constellatory juxtaposition; the prehistoric thus breaks into the present. The means of its appearance is not due to its "uncanny survival," but rather to the point where "our nets coalesced": a seemingly dialectical process in reverse, where a singular point doesn’t blossom upwards into an absolute space, but rather where the netting of space collapses downwards onto a single point. Hence what happens in the poem appears to constitute something of a reverse Hegelianism; the dialectical net growing smaller the more it moves back in time and approaches the prehistoric. But rather than a diminishing of consciousness that would theoretically accompany a reversal of dialectical consciousness (the move from the Hegelian absolute to immediate sense-perception), the coelacanth here seems to constitute something of a radical otherness. The event is "prehistoric" regardless of it having occurred in the twentieth century, and thus giving the coelacanth a discernable, almost supernatural, force. Interestingly, about the same time as the coelacanth’s discovery, Benjamin would remark that it is the technique of the historical materialist to redeem the forgotten shards of history and draw these "most vital aspects of the past into his net" (Arcades N1a, 1). The capturing of such a forgotten thing would hence represent something of a victory for Benjamin’s materialist historiographer. Against a perceived history that would see the fossil as relegated to a distant and unreachable past, Dewdney writes that The continued use of fossil fuels has released countless side-effects unknown to mankind. The highways are actually arteries carrying the lifeblood to an unarticulated primeval form using cities, oil refineries, jet and auto engines, factories, and any form of fossil fuel consumption to slowly replace the present composition of the atmosphere with the chemical composition of the atmosphere some 200 million years ago. After a certain critical point this atmosphere will become capable of generating the life-forms essential to this ancient form. (Palaeozoic) Once again, Dewdney recognizes that built on top of prehistory is a present day that always threatens to collapse back into it. Here, the guise of progress deteriorates in light of the fossil fuels that motor its technology. The present would like to use the past only to propel itself ahead and further away from it. But the further it seemingly goes from the past, the closer it moves toward it, leading to an eventual demise of man and the return of prehistory. This eternal recurrence of the fossil echoes Benjamin’s own formulations on the ability to blast the epoch "out of the homogeneous course of history" (Selected 4: 396). Thus the fossil returns to debase man’s historical progress, subtly undermining the certainty in which modern society cloaks itself. It is the poet’s responsibility to illuminate these fossils, thereby becoming "a herald who invites the dead to the table" (Benjamin, Arcades N15, 2). The dead in Dewdney’s poetry gather around the "memory table": a subterranean locus analogous to water tables through which the dead project their voices. It is hence both the writer’s objective to allow the dead — long buried and forgotten beneath the footsteps of progress — to speak.

Fig. 2. Rescuing the lost forms of yesteryear: The materialist historiographer at work. "Seminars on Science: diversity of Fishes." american Museum of Natural History. 2001. American Museum of Natural History. http://www.amnh.org/learn/pd/fish_2/photo_gallery/coelacanth.html

Display large image of Figure 2

10 As is the case with Dewdney, Benjamin’s attempt to give a voice back to the dead also constitutes a sort of reverse Hegelianism. If Hegel’s concerns lie with "freeing determinate thoughts from their fixity" (Phenomenology 20), then Benjamin’s raison d’être comprises of an attempt to, according to adorno, turn "its object to stone" (Notes 2: 228). This Medusa gaze of Benjamin’s thus allows him to articulate the silent voice of the fossil; in fossilizing the living, he levels the discursive playing field enough to allow the dead to reassemble themselves on the plane of the present. As adorno writes, Benjamin was "driven not merely to awaken congealed life in petri-fied objects … but also to scrutinize living things so that they present themselves as being ancient, ‘ur-historical’ and abruptly release their significance" (Prisms 233). In doing so, Benjamin is able to grind the Hegelian dialectic down to a halt.

11 Benjamin thus turns his focus to fossilized, pre-dialectical forces in an attempt to mine whatever revolutionary potential may lie there. According to adorno, "The petrified, frozen, or obsolete inventory of cultural fragments spoke to [Benjamin …] as fossils" (qtd. In Buck-Morss 58). It is within the early drafts of the arcades Project (of the late 1920s), in Benjamin’s first elucidation of the proto-historical, that we first find these fossils articulated in his work. Benjamin writes that "a strange rapport and primordial relatedness is revealed in the landscape of an arcade" (Arcades a°5). The fossilized animals are often indistinguishable from the subjects in Benjamin’s arcades, or rather, the fossil ossifies the subject via its inability to become mediated: a woman in the arcades with permanent waves in her hair has a "fossilized coiffure" (Arcades c°1; translation modified).3 Benjamin further writes that "as rocks of the Miocene or eocene in places bear the imprint of monstrous creature from those ages, so today arcades dot the metropolitan landscape like caves containing the fossil remains of a vanished monster" (Arcades r2, 3). Such fossils seem to cast a pall over modernity, and though unnoticed by most, Benjamin attempts to memorialize them and isolate them from their subsequent sublation into catastrophic history. These fossils lie suspended in time, untouched by the temporal flux of dialectical speed. According to adorno, Benjamin has "succeeded in refining the concept of natural history by taking up this theme of the awakening of enciphered and petrified objects" ("idea" 119). These fossilized objects speak through the dialectical image. Adorno further writes that in Benjamin’s work, the "dialectic comes to a stop in the image and … cites the mythical as what is long gone: nature as primal history" (qtd. In Benjamin, Arcades N2, 7). For this reason dialectical images "are truly ‘antediluvian fossils’" (qtd. In Benjamin, Arcades N2, 7).

12 The fossil as emblem of the dialectical image is employed by Benjamin in part to oppose a philosophical tradition that has consistently predicated human subjectivity, in the name of progress, on the sacrifice of the animal. It is something like a wrench thrown into the temporal cogs of humanity. As derrida writes, with Benjamin in mind, "carnivorous sacrifice is essential to the structure of subjectivity" (247). The elimination of the animal clears a space for the human subject. This sacrificial economy was also identified by Benjamin’s colleague Georges Bataille, who rescued the arcades Project from historical oblivion (he hid the manuscripts before the Nazis overran France). Bataille writes that if "the animal which constitutes man’s natural being did not die … there would be no man or liberty, no history or individual" (12). Bataille’s comments come from an article on Hegelianism, and though not cited, it calls to mind Hegel’s speculation that "When suffering a violent death, every animal has a cry in which it expresses the annulment of its individuality" constituting a "negative self" (Philosophy 3: 140). No longer the mere "abstract and pure vibration" of its regular voice (Philosophy 3: 106), the animal’s death cry forms a sort of bridge between the animal’s voice and the voice of the human. We understand the animal most clearly when it is dying. This "annulment of individuality" (or, rather, "sublation of individuality," which may be a better translation of Hegel’s aufheben) allows us, according to Giorgio Agamben, tounderstand why the articulation of the animal voice gives life to human language and becomes the voice of consciousness. The voice, as expression and memory of the animal’s death, is no longer a mere, natural sign… . Although it is not yet meaningful speech, it already contains within itself the power of the negative and of memory . (45)Within the death cry of an animal, according to Hegel, the voice "constitutes a negative self or desire, which is an awareness of its own insubstantial nature as mere space" (Philosophy 3: 140). Though the animal ceases to be, its voice lingers on as an "expression and memory of the animal’s death" for the living, and language is founded on this fundamentally negative ground. The remainder of the animal’s voice, as a "sublation of its individuality," constitutes, according to agamben, "an immediate trace and memory of death" (45). Hence, this lingering, fossilized trace of death provides a foothold for the dialectic to ground speech and herald meaning, but at the same time it becomes cancelled out and repressed by the subject.

13 Both Dewdney and Benjamin reanimate this death in the emblem of the fossil, and save it from being absorbed in the Hegelian dialectic. For Dewdney, the poet’s responsibility is to get out of the way and allow the history of the "creatures themselves" to speak in a language "uncorrupted by humans" (Predators 8). Hence the fossil becomes a sort of conduit for these voices, which would imply a skirting of the Hegelian dialectic of animal sacrifice. If death is indeed a "dialectical central station" (Benjamin, Arcades C°2), the living fossil has somehow missed its train. Contra a western metaphysics that has theorized the human voice as a progressive flux emanating from the animal, reaching its apotheosis in death, Dewdney freezes this death and suspends it in the dialectical image, allowing it to flash up in the present day to haunt those who may have forgotten it.

14 If our subjectivity is predicated on the death of the animal, then the fossil constitutes a hypostatization of this process. Benjamin returns to the dying animal in order to halt the dialectical process and to compose a "static conception of movement itself" (adorno, Notes 2: 228), or a "standing wave" in the language of Dewdney’s poetry (Palaeozoic). The living fossil of both these writers’ work signifies an outside of the dialectical process; since its death is always already prior to its existence, it remains a perpetual beyond-death. Death hence remains immediate in their work, rather than properly removing itself to preserve the continuity of history. We can say that whereas Hegel invokes the animal, sacrificing it to ground the taking-place of language, then Dewdney and Benjamin freeze the process, and invest into the dead animal — qua fossil — a synchronic animation. However, in Benjamin’s work the dialectic of the animal has somehow gone awry; the woman with fossilized hair would hence point to a gross, improper collision between the animal’s death and the living subject, a profane simultaneity. As this is with Dewdney’s work, where the fossil and subject become chiasmatically switched, and subject freezes while the fossil flits away. In the living fossil, the sacrificial death of the animal is not possible, since it has not fully sublated itself, as per Hegel’s formulation. Lacking the means of transcendence, the fossil in Dewdney’s poetry runs rampant, petrifying subjects into rigidity.

15 Additionally, this breakdown of the dialectic is especially adept to adumbration in the domain of poetry. Indeed, according to Benjamin, a dialectics at a standstill can best be articulated with the enlistment of art. Art thus can become, as adorno describes it, a means to "consolingly recollect prehistory in the primordial world of animals" (Aesthetic 119). Furthermore, Benjamin’s call for a methodological adoption of montage (Arcades N1a, 8) would indicate that materialist historiography can gain vital strategic vantage points from artistic practice, making the poet a crucial element for the propagation of such a perspective.

16 The poet, then, is well suited for the purposes of the historical materialist, armed as he or she is with the tools of its trade. Beyond montage, allegory is a vital strategy for historical materialism; as Max Pensky explains, allegory opposes "a petrifying and corrosive depiction of historical decay to the sacrificial image of eternity" (Melancholy 113). Parataxis also provides a good example of this suitability, placing objects, as it does, not in order to be synthesized to a higher level, but to be freezed in a static constellation. Interesting to note here is Dewdney’s aforementioned paratactical experimentations involving "words that are standing waves between the words" (Alter 39). The realization that "there are poems that are the standing waves between real poems" (Alter 39) is a paratactical strategy akin to the teasing out of dialectical images from a so-called "real" history, a history that has a tremendous capacity for the neglect and disregard of small but nonetheless important historical phenomena. In a more general sense, the form of the poem can more easily shatter the notions of continuity and holism that are so prevalent in other discursive spheres.

17 Poetry, then, need not jettison history to be politically or aesthetically progressive. Indeed, for Benjamin, the Surrealists and Symbolists created much more vanguard movements than their antecedents, the italian Futurists, whose aesthetic espousals of the new eventually led them to an embrace of fascism. The special status of Surrealism in his work was solely due to their ability to recognize historical flashpoints as teeming with revolutionary potential. Dewdney’s poetry, needless to say, is affiliated more with the Surrealist/Symbolist tradition than with other twentieth-century movements, given his concentrated juxtaposition of past and present. Benjamin’s appraisal of the Surrealists for finding "the revolutionary energies that appear in the ‘outmoded’" dovetails neatly with Dewdney’s caveat that "abandoned electrical machinery factories shall be worshipped" (Selected 2: 210; Recent). Rather than considering the avant-garde as solely focused on the contemporaneous, as negating all that came before it in a misplaced faith in progress, this renewal of the past becomes more of a revolutionary gambit, Benjamin insists, since the past is where a "primordial mode of apprehending words is restored" (Origin 37). This "primordial mode" is conceivably more radical than any aesthetic that discards the past with disdain. "The mineral is the lowest stratum of created things. For the poet, however, it is directly joined to the highest. To him it is granted to see in this chrysoberyl a natural prophecy of the petrified, lifeless nature concerning the historical world in which he himself lives" (Illuminations 107). In Dewdney’s poetry, this primordial mode not only takes its form solely in the description of prehistoric phenomena; his utilization of language shares a similar structure. This is most obvious in, though not limited to, "The dialectic Criminal," where Dewdney rearranges dead phrases into new configurations, thus placing them into new flash-like constellations of meaning:You on the other hand, you put your foot in your mouth & bit off more than you could chew. Now with what’s left you put your foot in the door and then accuse me of changing my tune? I had to change my tune in order to face the music. (Alter 94)This is to show that the "connotative properties" of language "are like the soft parts of a decaying fish, they rot away and leave only the skeleton to be preserved as a fossil" (Alter 81). These dead phrases are seemingly, on first approach, but dead bones that Dewdney jostles around. Though, as elsewhere in Dewdney’s work, this decay is not by any means the final stage of the process; dead words "do not really rot away," but rather "it is as if the fish’s flesh was continuously reassembled, fossilized particle by particle" over "centuries of change" (Alter 81). Like the dialectical image, which comes from the land of the dead in order to shock the viewer into a new understanding of historical reality, the dead language of Dewdney’s poem is resurrected from its subterranean dwelling and put to similar use. The living fossil reconfigures itself. Perhaps Benjamin’s famous intention to assemble a book solely out of quotations shares a similar strategic aspiration.

18 Like Charles Baudelaire, Dewdney’s own political convictions are ambiguous, especially in recent years, which have seen him adopt a dubious sort of technocracy. But as Benjamin was able to see Baudelaire’s revolutionary potential through the haze of such contradictions, so should readers of Dewdney attempt the same strategy. In revitalizing lost and forgotten phenomena of history, Dewdney’s poetry provides an adept critique of humanity’s perceived mastery of the world. In doing so, such phenomena are saved from the graveyard in which history dumps its unwanted dead. While this strategy currently receives critical appraisal from such poets as Susan Howe, who similarly seeks to "lift from the dark side of history, voices that are anonymous, slighted — inarticulate" (17), Dewdney’s poetic/political tactics receive scant attention. This is especially lamentable when Dewdney’s work is all the more radical in its debasement of humanism than Howe and other poets, who are reluctant to stray from their anthropomorphic confines. Dewdney’s radical edge is that he attempts to find the animal’s, rather than the human’s, lost voice, which remains a much more difficult project. But while there may be "immense odds against the fossil’s occur-rence" (Palaeozoic), this nonetheless should not persuade one to ignore it altogether. Rather, Dewdney’s poetry is a diving into the rapids of historical progression in order to save these lost voices of natural history.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor. Aesthetic Theory. Trans. And ed. R. Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 1997.

—. Hegel: Three Studies. Trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen. Cambridge: MIT P, 1993.

—. "The Idea of Natural History." Trans. R. Hullot-Kentor. Telos 60 (1984): 111–24.

—. Notes on Literature. 2 vols. Trans. Shierry Weber Nicholson. New York: Columbia UP, 1992.

—. Prisms. Trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber. Cambridge: MIT P, 1981.

Agamben, Giorgio. Language and Death: The Place of Negativity. Trans. K. Pinkus and M. Hardt. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 1991.

Bataille, Georges. "Hegel, Death and Sacrifice." Trans. Jonathon Strauss. Yale French Studies. 78 (1990): 9–28.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Trans. H. Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Ed. R. Tiedemann. Cambridge: Belknap/Harvard UP, 1999.

—. Gesammelte Schriften. Ed. R. Tiedemann and H. Schweppenhäuser. 6 vols. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1972–1982.

—. Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken, 1968.

—. The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Trans. J. Osborne. London: Verso, 1985.

—. Selected Writings. Ed. Michael W. Jennings et al. 4 vols. Cambridge: Belknap/Harvard UP, 1996 – 2003.

Bök, Christian. "Radiant Inventories: A Natural History of the Natural Histories." Canadian Poetry 32 (1993): 17–36.

—. "The Word entrances: Virtual realitics in Dewdney’s Log Entries." Studies in Canadian Literature 18.2 (1993): 17–26.

Buck-Morss, Susan. The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Cambridge: MIT P, 1989.

Derrida, Jacques. "Force of Law: The ‘Mystical Foundation of authority.’" Acts of Religion. By Derrida. Ed. Gil Anidjar. New York: Routledge, 2002. 230–300.

Dewdney, Christopher. Alter Sublime. Toronto: Coach House, 1980.

—. A Palaeozoic Geology of London, Ontario: Poems and Collages. Toronto: Coach House, 1973. N. pag.

—. Predators of the Adoration: Selected Poems 1972–1982. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1983.

—. The Radiant Inventory. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1988.

—. Recent Artifacts from the Institute of Applied Fiction. Montreal: McGill University Libraries, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, 1990. N. pag.

—. Spring Trances in the Control Emerald Night. A Natural History of Southwestern Ontario, Book 1. Berkeley: The Figures, 1978.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "The Poet." The Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson Vol. 3. Ed. Alfred R. Ferguson and Jean Ferguson Carr. Cambridge: Belknap/Harvard UP, 1983. 3–24.

Hegel, G.W.F. Phenomenology of Spirit. Trans. A.V. Miller. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1977.

—. Philosophy of Nature. Trans. M.J. Petry. 3 vols. London: Allen and Unwin, 1970.

Heinimann, David. "A Conversation with Christopher Dewdney." Public Works. London: University of Western Ontario, 1985.

Hepburn, Allen. "The Dream of Self: Perception and Consciousness in Dewdney’s Poetry." Canadian Poetry 20 (1987): 31–50.

Highet, Alistair. "Manifold Destiny: Metaphysics in the Poetry of Christopher Dewdney." Essays on Canadian Writing 34 (1987): 2–17.

Howe, Susan. "Statement for the New Poetics Colloquium, Vancouver, 1985." Jimmy & Lucy’s House of "K " 5 (Nov. 1985): 13–17.

Jennings, Michael. Dialectical Images: Walter Benjamin’s Theory of Literary Criticism. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1987.

Jirgens, Karl. Christopher Dewdney and His Works. Toronto: ECW, 1994.

Lecker, robert. "Of Parasites and Governors: Christopher Dewdney’s Poetry." Journal of Canadian Studies 20.1 (1985): 136–52.

O’Brian, Peter. "An Interview with Christopher Dewdney." Rubicon 5 (1985): 88–117.

Pensky, Max. Melancholy Dialectics: Walter Benjamin and the Play of Mourning. Amherst: Massachusetts UP, 1993.

—. "Method and Time: Benjamin’s Dialectical Images." The Cambridge Companion to Walter Benjamin. Ed. David S. Farris. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004. 177–98.

Tiedemann, Rolf. "Dialectics at a Standstill: Approaches to the Passagen-Werk." The Arcades Project. Trans. H. Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Ed. R. Tiedemann. Cambridge: Belknap/ Harvard UP, 1999. 929–45.

Notes