Articles

On Reflexivity:

Tribute to Catherine Kohler Riessman

This paper is a tribute to Catherine Kohler Riessman, whose imprint on the field of narrative studies is legendary. It draws on some of her most influential publications to highlight her enduring commitment to and practice of researcher “reflexivity” and how her scholarship has influenced my work. I draw upon several of Cathy’s most influential publications to highlight her model of reflexivity in practice—a tacking back and forth between research questions, the literature, the data we collect and interpretations we make, our intellectual biographies, politics, personal experiences, and research relationships. We can look to Cathy’s scholarship for the power of revisiting, re-feeling, revising and re-envisioning our data. Her brand of feminist scholarship serves as a guide for bringing intellectual labour; historical, political and theoretical change; and personal lives into closer relation.

1 This paper is a tribute to Catherine Kohler Riessman, who has given so much of herself to the field of narrative studies. Cathy’s generous stance as a person and as a scholar has inspired a generation of researchers, myself included. She embodies feminist scholarship—a combination of “hand, brain, and heart” working together, the kind of feminist work that feminist science studies scholar, Hilary Rose (1983) advocated years ago as the epistemological stance for the natural (and we can add social/humanist) sciences. Cathy’s hands, brain, and heart have shaped my life and work in so many ways, so it is especially hard to pinpoint a particular theme or driving concept of her work to highlight. That said, because I have had the privilege of participating in a writing group with Cathy and Marjorie DeVault for close to two decades, I have learned up-close about Cathy’s commitment to and practice of “reflexivity,” which is the topic of this paper and her most formative influence on my work.

2 I can remember vividly when Cathy came to a writing group meeting, both surprised by the invitation and reluctant to agree to write a chapter on reflexivity for The Handbook of Narrative Analysis. In her characteristically humble way, she asked, “What do I know about reflexivity?” coupled with “I’m done with writing for handbooks.” And yet, she felt pulled to agree because of her personal connection to and admiration for editors Alexandra Georgakopoulou and Anna De Fina. Of course, Marj and I were quick to point out that the arc of Cathy’s writing career was itself the heart of reflexivity, and that she had ever so much to offer.

3 Cathy’s (2015) article, “Entering the Hall of Mirrors: Reflexivity and Narrative Research” situates the concept of reflexivity in its anthropological groundings and most importantly, in her own personal encounters with reflecting and revising her interpretations of data over time. The article is especially generative to use as a teaching tool with students, which is a hallmark of Cathy’s scholarship.

4 She begins her chapter with a caveat, capturing the contradictions of the Handbook task:

This paper and its evolution was one of my absolute favorites to witness and comment upon in writing group. As Cathy notes in the chapter,

I think her words lift up and codify a valued practice of reflexivity—a tacking back and forth between so many things: research questions, the literature, the data we collect and interpretations we make, our intellectual biographies, politics, and personal experiences, all the time searching for the words (and for some images) and writing styles (including different genres of writing) to best advance our claims. Cathy’s chapter provides a wonderful model for thinking about reflexivity, grounded in her own beginnings as well as the beginnings of the concept within anthropology more generally. She ties her personal reflexive beginnings to the second-wave feminist critique of the “absent investigator in social science writing” (2015, p. 221) and to numerous feminist sociologists who guided her thinking (Krieger, 1991; Oakley, 1980; Reinharz, 1984; Smith, 1987; Stacey, 1988; Stanley & Wise, 1983). Cathy embraced the first-person “I” to acknowledge herself as the human instrument of research and to signal that a researcher’s subjectivity (sometimes called “bias”) is not something to be rooted out, but to be acknowledged and made transparent as part of the inquiry. Ever careful to name people who have influenced her thinking, Cathy’s citation practices stand out as part of her trailblazing feminist scholarship, naming those who influenced her in ways that have brought others (especially women and younger scholars) along with her.

5 In disciplinary terms, Cathy credits the field of anthropology for its earlier embrace of reflexivity rather than other fields (e.g. sociology and psychology), in large part because ethnography is the coin of the realm in anthropology and because of the field’s critique of ethnocentrism. As a practice, ethnography is based on immersion in an “other”/strange/exoticized society that the anthropologist aims to make “familiar” for readers. This feature of anthropological knowledge (making the “strange” familiar) shifted once Western anthropologists turned their gaze upon their own societies and indigenous anthropologists took up the skills of ethnography as a means to protect and enhance their languages, cultures, and resources being stolen (L. T. Smith, 1999). As written texts, ethnographies are themselves reflexive products, even if not fully recognized as such by their authors or their readers. We can say the same thing about narrative studies. Whether explicitly stated or not, narrative studies are mediated by a researcher’s own background and position; the theories and techniques used; the historical moment and political context in which the research is conducted; and the relationship between the narrator (interviewee) and listener (researcher) that shapes the co-construction of what gets said, heard, and told.

6 As a member of our writing group, I came to know and admire Cathy’s acute sensitivity to the question of how much a researcher’s feelings and personal experiences should be made public. She is persistently vexed by the question of how much self-awareness and transparency is enough and how much is too much (a line she carefully walks and writes about). Indeed, Cathy brings this topic up in her article by referencing the discussion between anthropologists Barbara Myerhoff and Jay Ruby (1982) in the introduction of their influential edited volume, A Crack in the Mirror: Reflexive Perspectives in Anthropology, because it reflects Cathy’s concern about the difference between “true reflexiveness” and “self-centeredness.” Joining others in both anthropology and narrative studies, Cathy warns about forms of reflectivity that overemphasize researchers’ feelings and personal disclosures that overshadow participants’ own experiences and accounts. I believe this enduring concern is part of Cathy’s charm and personal proclivities—she is never one to want to prioritize herself over others or to be made a fuss over. In the chapter, Cathy ties this debate to the social conditions and critiques of the time, especially about the “Me Generation’s” emphasis of self over community concerns (e.g. Lasch, 1979). Even if Cathy isn’t always comfortable writing herself into her texts, she has an exquisite eye for where others might, and I have been the fortunate beneficiary of this. I have thrived on and been sustained by getting her hand-scribbled notes on the margins of draft articles or book chapters, “Where are you in this?”—or triple check marks alongside a section where she acknowledges my effort to do so.

7 In “Entering the Hall of Mirrors,” Cathy references an article she published in 2002 that I also vividly remember her drafting in writing group, entitled “Doing Justice.” In this piece, Cathy turned the mirror onto her initial analysis of interviews with a woman she called Tessa, about her husband’s domestic violence, that she had collected as part of her research for the classic text, Divorce Talk (1990). In “Doing Justice,” Cathy reviewed Tessa’s storytelling, her own field notes, memories of their research relationship, and important documents she had collected since the interviews, including Tessa’s diary and drawings. Tessa had described being repeatedly raped by her husband, which, at the time, was legally permissible and not grounds for divorce. In her original analysis, Cathy (1990) documented her own role in the co-construction of the narrative and its meaning, with Tessa emerging from a victim to a triumphant survivor who was able to force her husband to leave. The violence within Tessa’s marriage had been especially hard for Cathy to listen to, a fact she alluded to in her first analysis but stopped short of probing or making public.

8 The 2002 publication illustrates the power of revisiting data. Cathy walks readers through her earlier analysis of Tessa’s account, questioning her hand in the co-constructed heroic portrayal of Tessa’s survival. She points to the historical moment and the politics and “victim discourse” of feminism in the 1980s. As times had changed, not only had legislation passed that prohibited marital rape, but so had feminist critiques of binary thinking (e.g., problematizing the dichotomy of classification as either victim or survivor). Meanwhile, reading Tessa’s diary and looking at her drawings forced Cathy to reassess a level of violence within the family that complicated the picture of Tessa’s hardships, as well as the moral message of courage and strength that Cathy admits she wanted her readers to take away from her initial interpretation of Tessa’s heroism. Cathy noticed a language of violence that was laced throughout Tessa’s poetry, as well as moments in the transcript that Cathy could see she had minimized in her earlier analysis, including Tessa’s own violence toward her husband and, Cathy suspected, her son. Furthermore, a follow up visit Cathy scheduled with Tessa had not turned out the way she had expected, leading Cathy to question whether the terms of their relationship as a friendship (more than a research relationship) were realizable and how, if at all, Tessa had benefited from the research relationship. Cathy laid bare all these twisted and sticky layers of reflexivity in “Doing Justice” (such an apt title for the piece). I remember it being a very hard piece for Cathy to write, and a work for which she had received hard feedback from others who read it. Returning to that 2002 article again in writing the Handbook chapter once again stirred the pot of her emotions, thinking, and analysis. Nonetheless, Cathy persisted with her hand, brain, and heart to critically re-examine her assumptions.

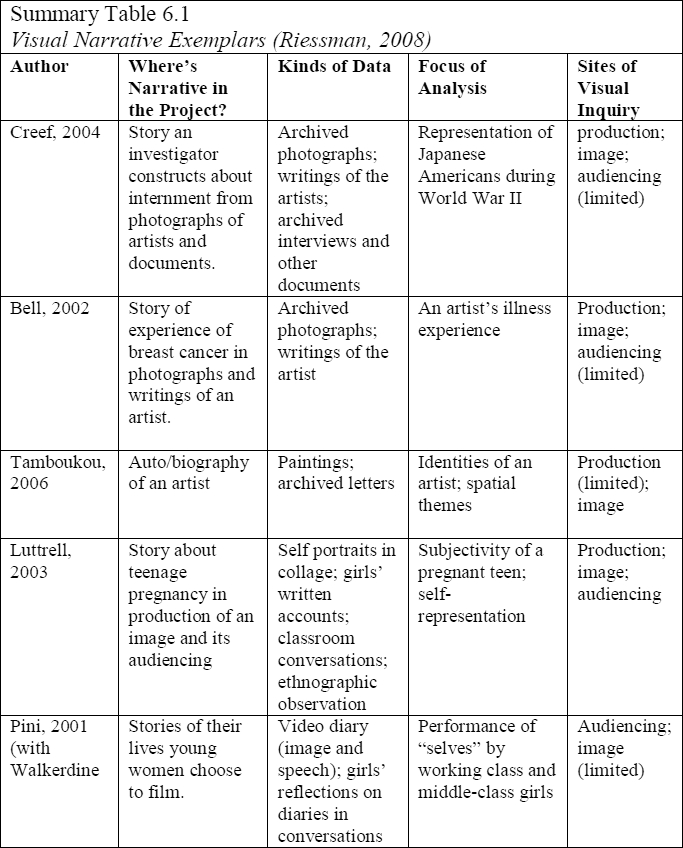

9 While not part of “Entering the Hall of Mirrors,” one of Cathy’s key contributions to the concept of reflexivity in narrative research, I believe, is her embrace of visual methods as an important means to expose and make visible things that might be seeable but not sayable. I attribute my own exploration of visual and arts-based research to Cathy’s early recognition and support for my use of collage-making with pregnant teens as a means to prompt and probe their lived experiences. Cathy helped me align my work with a visual narrative approach. I was beyond honoured when Cathy asked to include an exemplar from my research reported in Pregnant Bodies, Fertile Minds (Luttrell, 2003) in her volume, Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences (2008), an update to her earlier “little blue book,” Narrative Analysis (Riessman, 1993) that established her as an international authority in the field. In her updated volume, Cathy expanded, refined and made wide-ranging connections between networks of people around the globe and across fields, including social work, nursing, education, and communications research, using narrative methods. This book is another indispensable teaching tool with its Summary Tables that distill and codify the elements of each exemplar she has described in a chapter. For each type of narrative analysis that she discusses—thematic, structural, dialogue/performative, and visual—she offers tables that help researchers systematize their analytic choices and strategies to ensure attention is paid to (a) what definition of narrative is used, (b) transcription and how form and language is reconstructed for analysis, (c) unit of analysis, (d) attention to contexts, and (e) in the case of visual analysis, the sites of inquiry. By sites of visual inquiry, Cathy adapts the work of visual theorist Gillian Rose (2001/2012) to formulate methods for three types of visual narratives: the story of the production of the image, the story of the image itself and its content, and the story of how the image is read/understood by different audiences. Reading Cathy’s account of my process and her distillation of it in Summary Table 6.1 (Riessman, 2008) made me see my research process anew. Without being aware of it, I had incorporated all three sites of visual analysis in my design and analysis:

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1

10 I would go on to extend my embrace of visual methods with a more self-conscious eye in my next research project, thanks to Cathy’s influence. My longitudinal visual research, reported in Children Framing Childhoods: Working-Class Kids’ Visions of Care (Luttrell, 2020), put cameras in the hands of diverse children growing up in urban, working-poor and immigrant communities of colour to photograph their everyday family, school, and community lives over time (at ages 10, 12, 16, and 18). I was interested in considering what role, if any, gender, race, ethnicity, class (relative advantage), and immigrant status would have in how the young people would represent their lives and “what matters most” to them (one of the prompts for picture taking).1

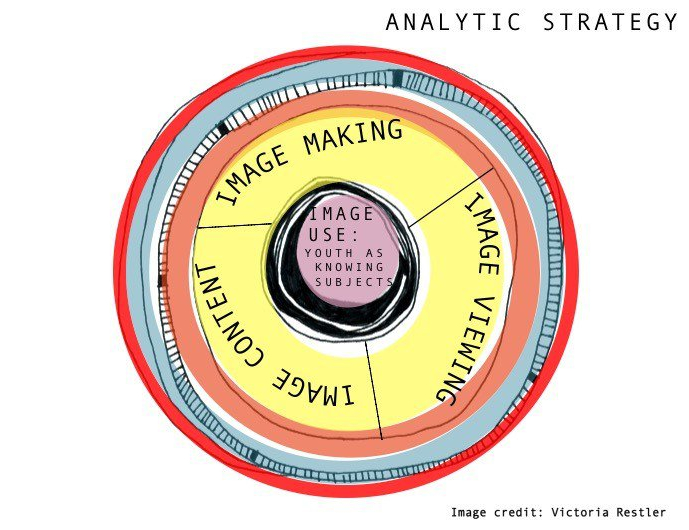

11 In doing this project, I came to realize the importance of four— not three—sites of inquiry, all of which provided glimpses into the kids’ meaning-making and how they expressed their intentions, subjectivities and agency through (1) image making, (2) image content, (3) image viewing, and (4) image use (Luttrell, 2010, p. 231):

To visualize my approach, I borrowed from the image/metaphor of a camera lens to suggest that the analysis among these four sites/“sights” of inquiry can be shuttered, widened, focused, minimized, and magnified, to name a few.

12 In terms of image-making, the project’s school context came into clear focus; for example, the research activities were understood by the kids to be an “assignment,” and certain conversations revealed the kids’ own self-judgments spoken in the voice of dominant school discourse (e.g., whether they had “stayed on task”). At the same time, the kids also made the “assignment” their own, often using the cameras for their own purposes and self-expression. For example, some took photographs to be given as a gift to a family member, others lent it to a family member who wanted to photograph a family event, still others handed their cameras to others take a picture of themselves “doing something good,” and still others “experimented” with the camera, taking photographs from “funny angles” to see what would result.

13 To analyze image content, I combined two approaches: content analysis and narrative analysis. The content analysis included coding for people, places, things, and activities (work, play, socializing); gaze and smile (or not); and idioms of posture and positions that revealed social positioning (adapted from Goffman, 1979; Lutz & Collins, 1993).2 The narrative analysis was case-based, tracing each individual child’s images and identifying narratives and thematic patterns, which was suggested to me by Elliot Mishler. I have Cathy to thank for introducing me to Elliot and the Narrative Working Group, which was invaluable to my development in narrative inquiry and for reining in the vast amount of data I had collected.

14 Unlike most “giving kids cameras” research, I designed the project to afford multiple opportunities for image viewing and with different audiences—an individual child and an adult interviewer; in small peer groups without adult direction; each child reviewing and revising a video clip based on their conversation with an adult interviewer describing their five favorite photographs (only two kids opted to make changes); and finally, the kids meeting as a group to decide which photographs to select for a public exhibition of their work. Each of these “audiencings” revealed different “truths” about why a child had taken the photo, what he/she had hoped to convey, and why it was important. The last viewing opportunity highlighted the power of revisiting data, not only for researchers, but also for participants. I asked the kids to re-view and reflect on their childhood photographs as a means to better understand their own development over time. Perhaps not surprisingly, I learned that the meanings that the kids attached to their photographs changed depending on context, their intended audience(s), and time. I wanted to preserve these multiple truths in the overarching narrative I would tell.

15 Inquiry about the kids’ image use was similarly rich in multiplicity as they used their cameras and photographs for self- and identity-making purposes—to communicate across and about social distinctions and cultural differences; to express love, gratitude, connection, and solidarity; to show pride and self-regard; to seek and express aesthetic pleasure; to defend against negative judgment; and to memorialize a past and imagine a future. In speaking about their own and each other’s images, the kids drew upon and were in dialogue with larger social forces and narratives outside the viewfinder, including discourses about immigration, racism, and anti-blackness, and deficit- and damage-based expectations about the schools, families, and communities in which they were being raised. The research generated an extensive audiovisual archive3 that I used with teachers, teachers-in-training, and graduate students learning to conduct visual research. I was struck by the extent to which the kids’ images invited reflexivity on the part of different adult viewers. Utilizing Howard Becker’s (1986) strategies for “attentive looking, not staring” at images, “naming everything in the picture to yourself and writing up notes” (p. 232). This process helped to flush out viewers’ assumptions, blinders, and projections of their own childhoods on the images. Again I turned to Cathy’s text, Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences, to help me systematize my approach and preserve all its moving parts, distinctive viewing contexts, and sites/sights of meaning-making. I came to call my overall approach a practice of collaborative seeing.

16 Cathy’s work and wisdom helped me systemize my approach, but even more, she encouraged my visual experiments throughout the analytic and writing processes. The first was to create collages from a series of the kids’ photographs as a means to re-see and re-represent their meanings in visual terms. For example, there was one series of images—“moms-inkitchens” photographs taken by the kids at age 10—that were predominant. Adult viewers often characterized these photographs as “ordinary,” “mundane,” “familiar,” and “stereotypical” (myself included, before I heard the children’s explanations). I wanted to disrupt these lenses and open space for an alternative viewing, one that could more closely honour the kids’ intentions and admiration for their mothers’ role in “feeding the family” (DeVault, 1991).4 As the project developed, and I began to think about how I could use visual and creative means to express some of my ideas, Cathy stood ready to watch and reflect with me. These efforts were integrated into the book’s accompanying website5 that feature five “digital interludes” which intentionally blur the borders between research and art, analysis and evocation, looking and feeling, ethics and aesthetics, seeing and knowing. Cathy’s awareness of the creative tension between image, text, and narrative helped to guide my journey.

17 Cathy was a witness, supporter, cheerleader, and most importantly, a friendly critic throughout my process—from the first stage of data collection to the completion of the book. Her sustained interest buoyed my spirit and confidence to take some risks, which is her enduring mark on my work, and for which I am forever grateful.

18 To conclude, Cathy’s model of reflexivity in practice is to revisit, rethink, re-feel, and revise. This is the lasting intellectual legacy she leaves to narrative studies. We can all look to her and to her scholarship for the power of revisiting data. We can look to her and her scholarship as a guide to a reflexive practice that brings intellectual labour; historical, political, and theoretical change; and personal lives into closer relation. I count myself among the many fortunate people whom she mentored, through gifts, friendship, welcome criticism, unending curiosity, care, wisdom, and insight.