Articles

Self-Narrative Elicitation in Counseling:

An Exploration of the Usefulness of Selected Interview Methods

An important element of many forms of counseling is the narrative articulation of the client experience. This article aims to define self-narrative elicitation methods, to explore their use in counseling, and to present a quantitative empirical examination of narrative interview instructions. It examines whether the self-narrative inclination and selected situational factors influence the narrativity level of the utterances when elicited by different types of self-narrative instructions. The results show that the utterances produced by three different types of instructions (open-ended question; photo-elicitation; life-asbook metaphor) do not differ in narrativity level. The narrativity of utterances measured micro-analytically on the lexical level remains independent from the external factors (sequence, topic, type of instruction). Given the level of narrativity and length of response, the three instructions are close to each other. At the same time the narrativity is significantly influenced by self-narrative inclination. It is worth acknowledging personal features that can change the way the story is told in interviews and thus affect the counseling practice.

The Value of Self-Narrative Elicitation in Counseling

1 It is now quite commonly maintained in psychology that telling stories is one of the defining characteristics of being human (e.g., Bruner, 1991; Hermans, 1999; McAdams, 2006). Telling a story about autobiographical experiences may be understood as an interpersonal activity that occurs in the scope of the so-called narrative discourse (Ochs & Capps, 1996); it may also be an intra-personal activity that concerns story construction and telling stories to oneself, for example in the form of internal dialogues (e.g., Hermans et al., 1993; Sobol-Kwapinska et al., 2019). In discussing the psychological value of narrative activity (both inter- and intra-personal) in the literature, making meaning of personal experience, valuing experiences, and constructing personality are emphasized and expressed in the idea of narrative identity (e.g., McAdams, 2018; Singer, 2004). It should also be noticed that narrative psychology has become a lively branch of psychology (Laszlo, 2008; Schiff, 2006), and one with a great impact on counseling in almost every approach (not exclusively in narrative counseling) and in many settings— especially clinical, educational, and vocational, where a host of narrative techniques of intervention and assessment are widely used (McLeod, 2003; McMahon, 2018).

2 The general professional counselor’s role is to facilitate the client’s work in ways that respect the client’s values, personal resources, and capacity for self-determination (e.g., Dryden & Mytton, 1999). It is often suggested that the “not-knowing” stance—in which the counselor remains open to the possibility of a different response—represents the core values of narrative approaches to counseling and psychotherapy (Speedy, 2000). McLeod (2003) shows a number of facilitative processes potentially associated with the experience of telling a story to an interested and empathic listener, such as the experience of being accepted, the opportunity for the client to discover that there are different stories that can be told about the same events and experiences, as well as the use of creation of a narrative account to make sense of a confusing set of experiences. We may say that helping the client to tell his or her story seems to be an important aspect of professional competence (McLeod, 2003). Tantam (2002) posits, however, that listening skills do not suffice, and that mental health professionals also need to shape the story. This suggests that the professional narrative competence of a counselor may be twofold—requiring first the capacity to encourage and give permission to the client to narrate by setting up favorable conditions, and second, the capacity to actively conduct an interview, rich in client narrative activity, by means of proper questions, as well as timing and other subtle verbal and non-verbal interventions.

3 It is assumed that practitioners and researchers elicit self-narratives because they expect additional psychological value resulting from the personal storytelling and the stories told (Hermans, 1999, Laszlo, 2008; McAdams, 2006). It should be emphasized that additional psychological value emerges not only from the process of storytelling, but also from the possibility of self-narrative analysis as an analysis of text (utterance, statement). Thus, self-narrative is valuable as a method of intervention as well as an assessment tool. How can self-narrative elicitation be useful for counselors, and what is meant by “additional psychological value”? Counselors both stimulate the process of narration (storytelling) and analyze the self-narrative (story). We focus here on the self-narrative as the product of storytelling.

4 First, the narrative structuring of individual experience in storytelling gives access to the client’s patterns for organizing experience in the form of the narrative structure (e.g., narrative grammar; Greimas, 1971). It may thus be assumed that the way of telling shows how the events and experiences are constructed and represented and the connections between them occur to the narrator’s mind. The organizing of events and experiences involves temporal connections (something happened and then something else happened), enriched by causal (something happened because something happened) and teleological (someone had intentions to make something happen) connections. Having access to these types of connections, we can explore the world as it is experienced by the author of the story. This perspective seems to be very significant in psychological counseling, which is idiographically oriented and focuses on professional help adjusted to the individual needs and potential of the client (McLeod, 2009; Speedy, 2000).

5 Second, self-narratives are full of meanings important for a given culture, social world, and collective experience. Many papers in the social sciences stress that elements of cultural heritage are automatically included in the autobiographical story and that the process of meaning-making is separated from external influences in neither the content of these stories (e.g., Angus et al., 2004; Chase, 2003; McAdams, 2006) nor the available narrative patterns (e.g., Gergen, 1998). Consequently, self-narratives elicited in a counseling setting carry information not only about the individual, but also about the socio-cultural environment and the degree of socialization or rebellion against the status quo of the social world.

6 A self-narrative also allows the narrative identity to be examined as a life story (complete with setting, scenes, characters, plots, and themes) that situates a person in the world, integrates a life in time, and provides meaning, purpose, and an integrative personal myth (McAdams, 2018). In his personality model, McAdams (2006) describes self-narratives as an existential dimension, connected with the attempt to make sense of an individual’s life at a point in time. This personality level is therefore quite difficult to assess psychologically. However, it seems that through quantitative and qualitative content analysis of self-narratives it is possible to obtain diagnostically valuable data from the life story. Counselors are able to recognize how the client synthesizes his or her experiences, how he or she integrates time perspectives and different social roles, and what kind of point the client’s life story carries. This kind of information is very valuable at the stage of gathering data to diagnose adequately and to plan the intervention accurately.

7 To summarize, eliciting self-narratives during interviews is diagnostically useful, especially for recognizing the integrative life-story personality level, to establish the way in which personal experience coexists with socio-cultural influences, and for recognizing the client’s idiographic ways of organizing individual experience.

Research on Methods Aimed at Narrative Elicitation

8 There has been little direct research on narrative-elicitation methods or instructions, and existing studies have mainly dealt with vocational practice. For example, there is a study on facilitators and barriers for narrative elicitation and setting goals in a particular example of person-centered care practice during admission interviews in health service (Naldemirci et al., 2020). The analyses show that the narrative elicitation consists of the following strategies: preparing for narrative elicitation; lingering in the patient’s narrative; and co-creating—that is, the practitioner’s and third parties’ engagement in—the patient’s narration. The skills needed in narrative elicitation are not the same as in medical history taking. They encourage ethical reflection, and the need for patients and counselors to adopt a broad life perspective (instead of a narrow perspective of the illness). Naldemirci et al. (2020) also draw attention to the co-construction of the narrative, concentrating on well-balanced self-disclosure and joint interviews with families (for other coconstruction issues, see more in Holstein & Gubrium, 2016). As far as the patients were concerned, they were not familiar with self-narrative in a medical context, but many of them considered such conversations to be personally meaningful. As the researchers insist, the study identified strategies of narrative elicitation in a specific ward, but there is need for further research addressing the contextual variations of the use of narrative in different settings. Recently three data collection methods (video diaries, narrative interviews, and semi-structured interviews) were compared in a children’s healthcare context (Litovuo et al., 2019). The authors concluded that narrative interviews with parents have the potential to capture temporal, spatial, locus, and organizational dimensions through stories and are well suited for mapping children’s experiences and the actors influencing them.

9 In psychotherapy and counseling, on the other hand, work with narrative is emphasized as a particular process of capturing the experience that changes in the healing direction. For example, emotion-focused therapy emphasizes the importance of the narrative unfolding of significant personal experiences and experiential awareness that lead eventually to emotional transformation and self-narrative reconstruction (Cunha et al., 2017). In recent years, meticulous research on changes in self-narration in the psychotherapy process has been developed (Montesano et al., 2017). Nevertheless, researchers’ attention has focused on how self-narration changes in psychotherapy rather than on the circumstances for inducing or stimulating a narrative with specific methods or instructions.

10 Thus, we know that eliciting self-narrative is a unique relational phenomenon based on co-construction and that it can lead to specific verbal data. However, research to date still does not provide insight into the factors that contribute to obtaining highly narrative material through the use of specific narrative instructions.

A Closer Look at Self-Narrative Elicitation Methods

11 Specific methods of conducting a psychological interview are preferable for setting up the proper conditions and stimulating the narrative activity of the client to better contribute to obtaining autobiographical narrative texts (Hardin, 2003; Kvale, 2007). The self-narrative elicitation methods, as we call them here, are concerned with the data collection (creation) stage during the qualitative assessment and intervention and are based upon an in-depth psychological interview, in which the subject’s (research participant’s) self-reflection appears.

The Structure of Self-Narrative Elicitation Methods

12 Such methods consist of a narrative stimulus (self-narrative eliciting instruction), which may involve the use of words (verbal stimulus), images (visual stimulus), or both simultaneously. The narrative stimulus helps the research participant to produce a free, undisturbed narrative utterance about his or her biography and inspires the participant to structure experiences narratively. Examples of self-narrative elicitation methods include McAdams’s life story interview (McAdams, 1995); Schutze’s (1987) narrative interview; photo-elicitation interviews (e.g., Glaw et al., 2017); life-line interviews (Cermak, 2004; Schroots, 2003); relational anecdotes paradigm interviews (Wiseman & Barber, 2004); and other common open-ended questions to facilitate narratively-structured autobiographical accounts (e.g., “Please tell a story about being a parent”). For example, in Schutze’s narrative interview, the verbal narrative stimulus (a broad general question about a personally meaningful event) appears at the beginning of the interview; the interviewer does not interrupt with any verbal interventions until the self-narrative has finished. As can be seen, the thematic orientation should freely refer to the participant’s biography and may have a broad or narrow range; it may cover the whole life (“tell me your life-story”) or be oriented toward specific events (such as in the life story method in which, among other things, the subject is asked to recount peak experience, nadir experience, earliest memory, and turning point; McAdams, 1995).

The Usefulness of Self-Narrative Elicitation Methods

13 The methods discussed here aim to obtain autobiographical narrative data (utterances) using a process of storytelling triggered by narrative stimulus. We suggest here that the usefulness is determined by the following criteria: method independence and the level of narrativity of the utterances obtained as a response to the narrative stimulus. Method independence is the method’s potential for not being subject to the circumstances of the interview situation or to the features of the research participant. It mainly concerns the independence of the instruction from external and personal factors. The second functional criterion is the narrativity level of the utterances obtained as a response to the narrative stimulus. The level of narrativity is defined by the extent to which the utterance fulfills the key criteria of a self-narrative (see also Habermas & Doell-Hentschker, 2017). In a good self-narrative method, the instruction provokes the participant to produce a narratively structured autobiographical utterance. The better the instruction, the higher the narrativity level of the utterance is expected to be that is evoked by the instruction.

Specific Aims and Research Questions

14 This study is a quantitative empirical evaluation of chosen qualitative counseling interview interventions, conducted to enrich knowledge of self-narrative elicitation methods and to estimate and assess the possible ways in which these methods work in practice in counseling. The complex evaluation of the usefulness of particular methods is difficult because of the variety of decisions made by the counselors conducting the interviews, the individual features of the people participating in them, and external circumstances that are difficult to control. However, it seems justifiable to examine the issue of the dependence or independence of how these methods function (especially the effects of the instructions) from chosen personality factors and situational circumstances, such as the interview topic or instruction sequence. Therefore, this study—quite uniquely in this field of research— is not only concerned with determining the level of usefulness of particular self-narrative instructions, but also with verifying whether external factors and individual differences in narration may modify in any way the method’s functional usefulness. The self-narrative inclination, understood here as a tendency to think about oneself in self-narrative categories and to reporting on these events and autobiographical experiences, is considered in this paper as an important variable of individual differences. If the functioning of the instructions is modified by such an individual tendency, then the self-narrative methods would hardly work autonomously.

15 In the context of these considerations, the following research questions were asked: Do differences in the narrativity level of utterances occur if: (a) different self-narrative elicitation instructions are used; (b) the sequence of giving instructions is different; (c) the person tells a story on a positive or negative topic; (d) the person has a low, average, or high self-narrative inclination; and (e) these factors interact. Additionally, we have described some of the self-narrative features that appeared after applying various instructions.

Methods

General Design of the Study

16 This research is situated within the empirical discussion of methods of collecting qualitative data in research and diagnostic interviews, especially in the context of psychological counseling. Empirical research on methods is one of the pillars of evidence-based assessment and practice (Hunsley & Mash, 2005). The more we know about such methods, including the interview, the more consciously and accurately they can be selected for diagnostic and counseling purposes (see also Miller, 2010). In this mixed-methods study we use a quantitative computer-assisted analysis of qualitative interview data (e.g., Fakis et al., 2014). Thus, first, we elicited self-narratives with an interview (qualitative methods). Second, we analyzed the self-narrations following the quantitative content analysis method. In psychology, an example of this approach is the work of Pennebaker (e.g., Tausczik & Pennebaker, 2010). In our study we measure narratives from a microanalytic approach (brief units, counting of frequencies relative to the total of a unit of measurement like words, formal criteria) in contrast to the macroanalytic approach (see Habermas & Doell-Hentschker, 2017). We used a traditional computer-assisted content coding method—a dictionary method (e.g., Nelson et al., 2018).

Main Research Stages and Participants

17 Empirical studies were designed, consisting of three stages: a questionnaire screening test to determine the base level of self-narrative inclination, qualitative interviews conducted with controlled selection of instructions, and a lexical content analysis of utterances.

18 First, at the screening stage (reaching 140 university students, 54 women, age: M = 20.96, SD = 1.43), the self-narrative inclination questionnaire (IAN-R) allowed three groups of individuals to be specified, differing in terms of self-narrative inclination (high, average, and low). Each group consisted of 12 participants. Second, qualitative interviews were conducted, employing the random use of two self-narrative elicitation instructions from the pool of the three prepared instructions (in sum, 72 self-narrative elicitation instructions in the group of 36 individuals). The interviews were all conducted by the same person, who was not aware of the questionnaire results, and took place at an academic facility. The people taking part in the research gave their informed consent to the interview, to having their utterances recorded with a digital voice recorder, and to the transcripts of their utterances being used in analyses and publications. In the interview stage, selected external situational circumstances were controlled, such as interview topic, sequence of topics, and instructions. Third, the lexical content analysis of utterances was applied to the 72 transcripts of self-narratives (every participant contributed two self-narratives).

Interview Topic and Sequence

19 The choice of interview topic, inspired by McAdams’ (1995) life-story method, was limited to two possibilities: positive (peak) and negative (nadir) experiences. Each participant in this research talked about both topics. The sequence of the topic was also noted, as the positive (and negative) topic might have occurred in the first or a second place. The whole interview lasted from 15 to 50 minutes.

Self-Narrative Elicitation Instructions (Narrative Stimuli)

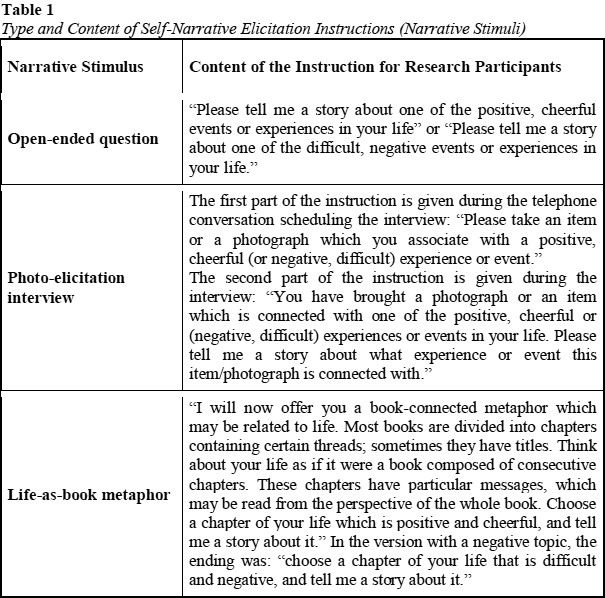

20 In this research, the following three different narrative stimuli (instructions) were presented to the participants: open-ended question; photo-elicitation interview; life-as-book metaphor.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1

21 The methodology for conducting the interviews in the present research was inspired by Schutze’s (1987) narrative interview, in which the four basic stages of conducting an interview are specified. The first stage is the introduction, which aims to ensure that the individual understands the rules of participation in the research and is ready to tell a story. The second stage consists of stimulating a free utterance by means of a narrative stimulus; this was the key moment in the research, in which one of the three self-narrative instructions was used. The third stage consists of asking internal (clarifying) questions, connected with the interviewee’s self-narrative. The fourth stage consists of asking external questions (connected with the topic of the research, but referring to previously omitted issues). Next is the interpretation stage, in which the researcher asks the participant about the importance of the event or experience in the context of his or her entire life. The conclusion stage involves discussing the interview and research procedure. A conversation on the two topics was conducted with all participants according to the same scheme (with the omission of the introduction and conclusion stages).

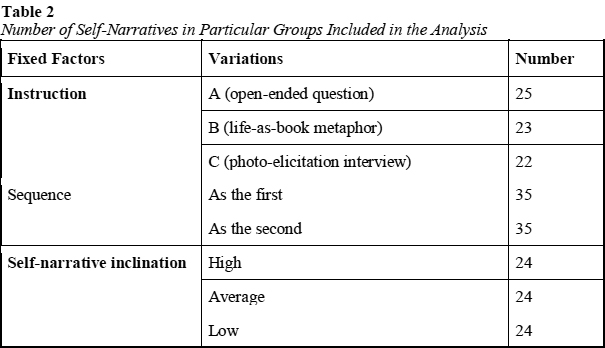

22 To sum up, the research was planned in such a way that, in all groups, three self-narrative eliciting instructions (A, B, and C) referring to one of two topics (positive [1] and negative [2] experience or life event) were used. Each participant was subjected to two out of three instruction types, so that each person talked about both a positive and a negative topic. The sequence of using the instructions and the topic (first or second) was also included.

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 2

Measures

Self-Narrative Inclination

23 To measure self-narrative inclination, the self-report measure was used (IAN-R, Soroko, 2013). The questionnaire consists of 30 items in 3 subscales: Narrative reporting (N; readiness to speak about one’s autobiography, e.g., “My stories are far more extended than other peoples’ stories”); Distancing (D; distancing oneself from one’s own experience, e.g., “Owing to the fact, that I reflect on my life, I better understand myself and other people”); and the Cultural aspect (C; drawing on cultural heritage in speaking about the self, e.g., “When I think about my life, a metaphor, a fable or other story comes to my mind”). The final result is the total sum of all the results obtained in the subscales. Scores close to the mean score were considered average (M = 92; SD = 15), high scores were at least one standard deviation above the mean score (above 107 points) and low scores were at least one standard deviation under the mean score (under 77 points). The IAN-R is reliable, and its validity is satisfactory (Soroko, 2013).

Utterance Narrativity Level

24 A pool of lexical narrativity indices in Polish was designed. The indices were based on counting selected words, parts of sentences, parts of speech, and phrases with a particular meaning, and referring them to the total count of words in the whole text. The indices belonged to the following categories: causality (cause-effect ordering index; e.g., “because,” “it was related,” “reason”); intentionality (ordering according to the intentions and aims of the character index; e.g., “in order to,” “plan”); temporal (time ordering index; e.g. “now,” “then,” “moment”); elements of the narrative structure (narrative structure index; e.g., “once upon a time,” “suddenly”); narrative and persuasive figures of speech (narrative structure, persuasion and rhetoric index; e.g., “listen to my story,” “it was the clue”); activity (activity occurrence index; A = verbs/adjectives); subjective responsibility for actions (index of actions taken by the subject; e.g., “myself”); and life reflection (distancing oneself and reflection on existential notions; e.g., “life,” “lesson,” “evaluated”).

25 To describe the transcript by means of these indices, an external code dictionary was created. Using Word Profiler (free word-counting software), the number of words in the whole corpus was established, as well as a list of unique words, together with the frequencies of all words. The total number of words amounted to 68,108, and 12.4% (8422) of these were unique. Each lexical element of the dictionary was assigned a code, by means of which its occurrences in all texts were counted. A text-coding program (a MS Office Word macro) was used on each of the 72 text samples (self-narrative transcripts that were the reactions of the research participants to the narrative stimulus) to give the number of occurrences of particular narrative categories in each text.

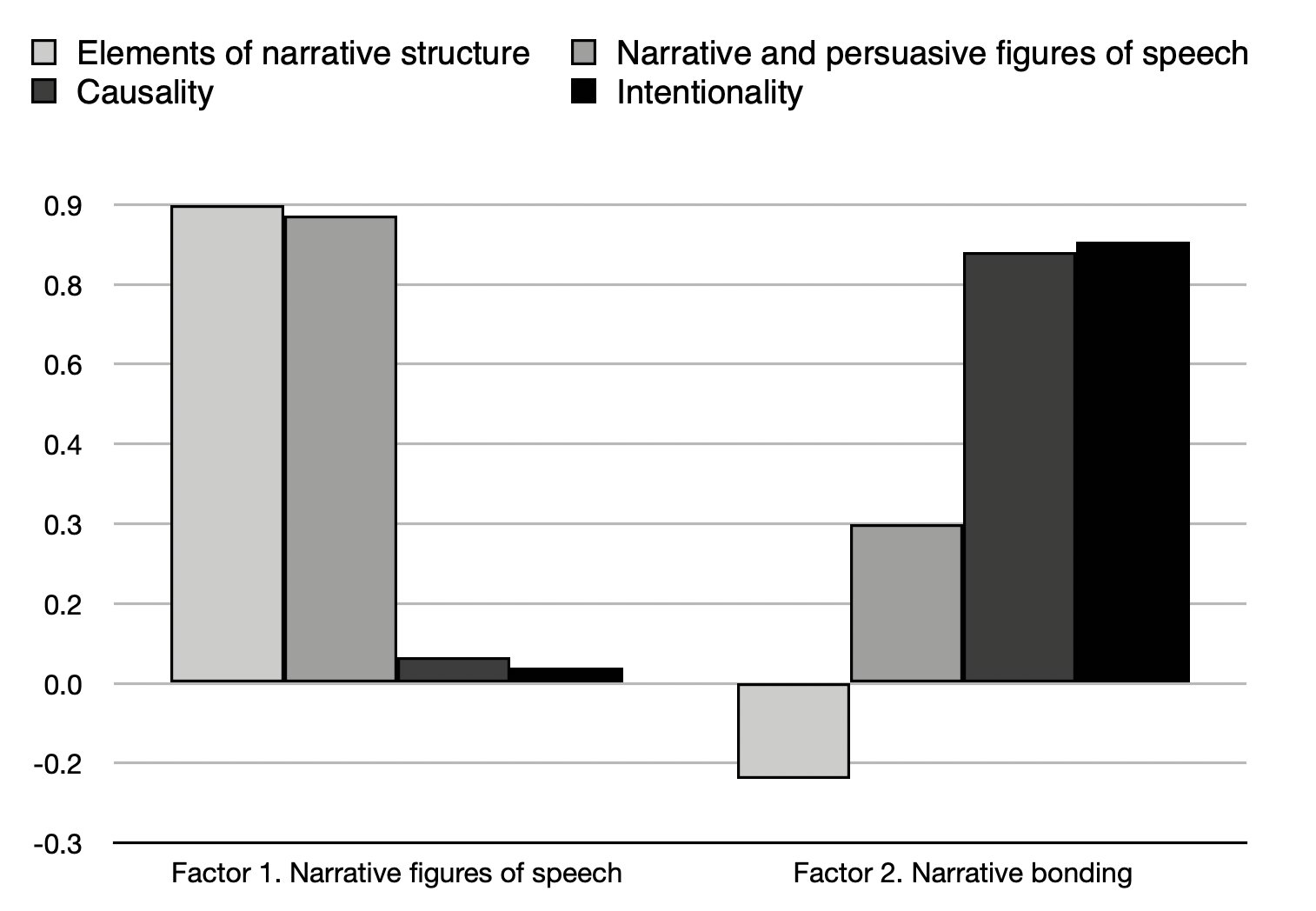

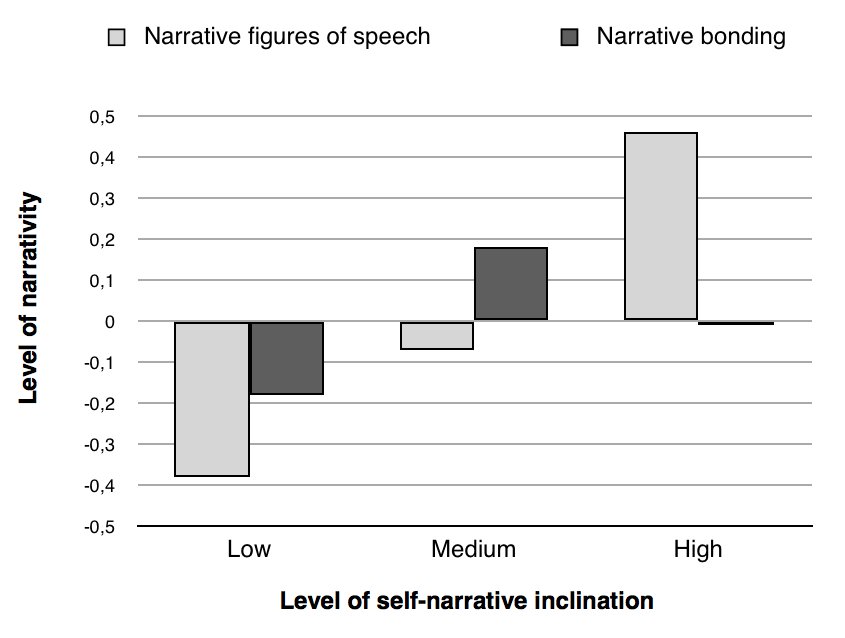

26 To facilitate further analysis, a generalized narrativity index was created to measure narrativity obtained from the partial indices, as discussed above. Exploratory factor analysis, which allowed for the generalization of indices to a higher level, was employed to achieve this. As a consequence, two factors were specified: the first consisted of elements of narrative structure (factor loading = .897) and narrative and persuasive figures of speech (.879), and the second consisted of intentionality (.847) and causality (.819). These factors are not correlated with each other (r = .06), and the total value of the explained variance is 77% (Fig. 1). The first factor was named narrative figures of speech, as it refers to utterance features in which numerous narrative figures of speech appear, serving to structure the narrative of the utterance or to enhance persuasive and rhetoric activity. This factor explains 41.3% of the variation. The second factor was named narrative bonding, as it refers to causal and intentional structuring—that is, the basic aspects of bonding events and experiences—in telling the story. This second factor explains 35.4% of the variation.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

27 In this way, two measures of narrativity (as both factors were independent from each other) were employed to determine the narrativity level of the utterances.

Results

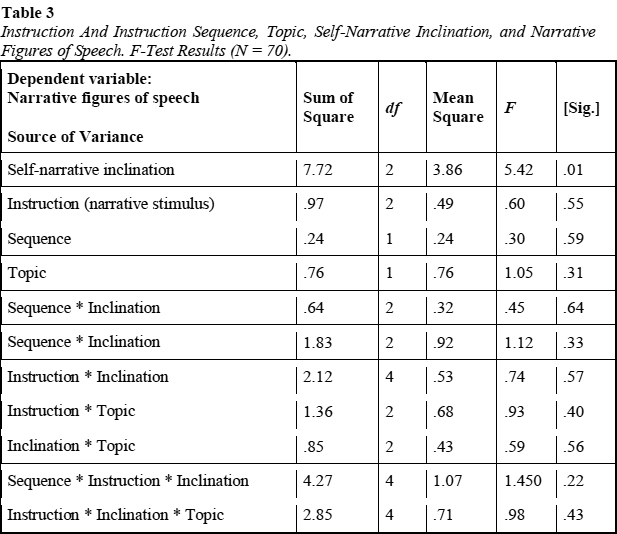

28 The research question referred to establishing the independence of the self-narrative eliciting instruction from external (topic, instruction sequence) and internal (self-narrative inclination) factors. To answer this question, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used, in which the dependent variables constitute two separate aspects of a generalized narrativity measure (narrative bonding and narrative figures of speech). The fixed factors, in different configurations, were: (a) self-narrative inclination (high, average, and low level); (b) instruction (A, B, C); (c) instruction sequence (as the first or second); and (d) topic (positive, negative; Table 1). The analysis showed that the narrativity level of the utterances does not depend on interview circumstances such as self-narrative instruction, instruction sequence, topic, or the interactions between them (Table 3).

Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 3

29 The narrativity level of the utterances obtained using the self-narrative methods and measured with the narrative bonding index also does not depend on the initial level of self-narrative inclination in the examined individuals, whereas the utterance narrativity level measured with the narrative figures of speech index does depend on the initial narrative inclination level (F(2, 52) = 5.42; p < .01; N = 70; eta2 = .037). To further specify between which variable levels the average differences occur, Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was used; this showed that, in the group of people with high self-narrative inclination, the narrative figures of speech index is significantly higher than for the group with low inclination (Figure 2).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

30 To summarize, self-narrative inclination proved to be an important source of variance in the narrativity level of utterances (narrative figures of speech) obtained in interviews, regardless of the type of instructions used.

Exploratory Analysis of Reactions toward Self-Narrative Stimulus

31 To answer the exploratory question about the characteristics of the narratives created as a result of the narrative stimulus, descriptive properties of the texts were controlled, such as the length of continuous speech after the narrative stimulus (number of words); delay of responding measured in seconds; and type of event that was evoked (specific, generic, period). The interviewer also delivered her personal experiences (field notes).

32 The number of words in the response to a narrative stimulus was counted (M = 317.4; SD = 222.5; min. 76, max. 876; Shapiro–Wilk W = .86; p < .001), and we coded the material for response delay measured in seconds and the type of the event evoked (according to the Self-Memory System, e.g., Conway & Loveday, 2015). An independent samples Mann–Whitney U test showed no significant differences between positive and negative topics regarding word count or response delay (U = 523; p = .086; U = 650; p = .68). The three narrative instructions did not differ in the number of words of the first response, measured from beginning to coda (Welch’s F (2, 46.13) = .2795; p = .757).

33 However, the three methods differed in terms of the type of event evoked (chi2 (4) = 33.30, p < .001). In our study, the methods used gave us the following percentage of three types of memories: specific memory (63.9%; e.g., a fire, the moment of becoming engaged, first day at work), period of life (26.4%; school; “my first boyfriend”, journey to China), generalized memory (9.7%; relationship problems; Christmas). We noticed that simple open-ended question led to recollection of a specific event in 84% cases, the recollection of a period of life was observed in only 16% of cases, while generalized memory was absent. Similarly, after photo-elicitation questions, the response was specific in 87% of cases and generic in 3%, while none focused on a life period. By contrast, the book metaphor contributed mostly to eliciting life period memories (62.5%), with only 20.83% for specific events and 16.67% for generic memories.

34 The three methods also differed in terms of response delay (Welch’s F (2, 34.45) = 15.75; p < .001). The photo-elicitation question was the easiest to answer at once (M = .13; SD = .63; SE = .13), while the simple open-ended question required about two seconds to answer on average (M = 1.9; SD = 2.5; SE = .52) and the book metaphor was the most demanding (M = 4.56; SD = 4.68; SE = .93). The highest difference in the delay was between the photo-elicitation intervention and the book metaphor (Games-Howell post-hoc test = 4.430, p < .001; however, the other differences were also statistically significant.

35 During a qualitative analysis of the participants’ reactions to the interview procedure, the following unique features were noticed. Photo-elicitation was a vibrant experience for both the interviewer and interviewee. Participants sometimes were not able to select one photo or one thing to bring with them, so they came with multiple items. Sometimes they said they had not brought an object with them, but they thought about something (a building, a chair). At other times, the item was replaced with something less physical, for example, the date of an event. The talk was not only immediate, but also became an exchange of ideas, and the story appeared after small talk. It was also challenging for the interviewer to remain in the background. The interviewee insisted on active participation, and it would not have been natural to refuse this open invitation. Interviewers reported that it was very inspiring, and the other parts of the interview (clarification and reflection) were often unpredictable. For example, some participants started to reflect on the process of choosing the photos, and others tried to tell a single story about three photos they brought with them.

36 It seems that an important role was played here by the earlier telephone conversation and the time left before the meeting, in which the subjects could prepare for the conversation and take control of it. Participants often depicted the photo-elicitation interview instruction as exciting and as bringing insight and self-reflection. The book metaphor inspired some of the participants to give titles to life chapters, but it was not common (3 cases). It took time to present the whole instruction, and perhaps evoked a kind of not knowing whether everything went well. The life-as-book metaphor instruction provoked many comments and questions before the storytelling began. The open-ended question instruction was considered obvious and received little comment.

Discussion

37 The basic research problem is concerned with verifying whether the usefulness of self-narrative elicitation instructions is subjected to external and internal circumstances. Instruction usefulness was evaluated on the basis of utterance narrativity level, which was established with two generalized utterance narrativity measures: narrative figures of speech and narrative bonding. The influence of instruction sequence and topic (external circumstances) and of self-narrative inclination (personality feature) on the utterance narrativity level was tested. The answers to the research questions indicated a lack of difference in the narrativity level of utterances when the following were considered: (a) different self-narrative eliciting instructions, (b) instruction sequence, (c) positive or negative instruction topic, and (d) interaction of these factors. The situational factors considered thus appeared to have no influence on the narrative level of the utterances.

38 We found a lack of differences in the narrativity level when different instructions were considered. This might seem controversial in light of the many recommendations for particular self-narrative elicitation instructions for psychological interviews present in the literature. It is therefore probable that the analyzed instructions are equally useful (or useless) in eliciting self-narrative. That is, the significant limitation of this research is the fact that it is not known whether instruction usefulness is high (see Limitations section, below). Nevertheless, the narrativity of the utterances in response to the narrative stimulus may remain independent from external situational factors, such as the instruction itself and the topic or sequence of giving instructions. This is an important conclusion, and one that suggests the possible independence of a person’s narrative activity (storytelling) from external factors. However, this independence refers to a lexical level of analysis of narrativity. By taking a macro-analytical perspective, we are able to see something more. The results of exploratory analyses suggest that the responses (and the process of arranging the stories) in response to the three instructions differed both in terms of the type of memories and the time it took to start the storytelling. The time can be understood as an effect of the difficulty or non-obviousness of a given instruction (in our case a book metaphor was the example). The book metaphor with the reference to the chapters could make it more difficult for people to deliver specific memories. It is likely they tried to look at the course of their life from a distanced view and generalized experiences more. Taking into account the observation (Naldemirci et al., 2020) that an important element of the strategy of using narrative methods is proper preparation, we suggest that the book metaphor needs to be clarified to its subjects or clients.

39 In our study, the narrative figures of speech and narrative bonding indices, as well as the length of the utterances, showed no difference based on whether the clients were telling a story about a positive or a negative event or experiences. This does not mean, in general, that the level of narrativity is equal regardless of the affect. Perhaps the emotional subject of the interview should be more differentiated to reveal such differences. Research shows that narrativity is higher in narratives about angering and scary events than in narratives of sad, happy, or pride-inducing events (Habermas et al., 2009).

40 The sequence of narrative stimuli also did not appear to influence the narrativity level of the utterances. We may refer to the length of contact with the interviewer here, and, in practice, this often is not the case. The nature of psychological contact is such that it deepens with time. However, time is not enough—the quality of the relationship is needed. There is no doubt that the context of the therapeutic relationship and other therapeutic factors (especially common factors) influence the outcome of therapy, although the question of the mechanism of change is still relevant (cf. Cuijpers et al., 2018). Likewise, more open self-expression can be achieved through psychological contact (rapport), contract, or more broadly, the co-construction of interview data.

41 The discussion of the role of external circumstances and the psychological situation in producing narrative statements is still ongoing. For example, research shows that people, for personal (biographical) but also situational reasons, can tell stories with different properties on a prompted topic, so controlling these factors in narrative studies is recommended (Soroko, 2020).

42 The personality factor—the self-narrative inclination—proved to be significant in analysis of the changes in the utterance narrative level, determined by the narrative figures of speech index. This effect was not obtained for the narrative bonding index. Individuals with a high self-narrative inclination construct narrative utterances that are quite narratively structured (but not necessarily full of causal or intentional relations), regardless of the way in which the self-narrative elicitation instruction is employed. It may therefore be said that the instructions function differently for individuals with high and low self-narrative inclination, which would indicate that the instructions hardly function autonomously and are dependent on personality factors. The instructions may therefore not be equally useful (at least in the scope of narrative structuring) with different people. In light of this research, it seems justifiable to note that when a counselor comes across problems with a client’s storytelling (the client’s utterances are not structured in a narrative form), this may not reveal unconscious resistance issues or intentional hiding of selected information, but may reveal the client’s low inclination to tell autobiographical stories. Awareness of this fact can help avoid certain diagnostic artifacts, such as overestimating resistance issues or a lack of subordination. It may even decrease some unrealistic expectations, such as the belief that using a self-narrative method guarantees a highly narrative utterance or that it prevents extra-narrative linguistic expressions, like descriptions or argumentations, from being undervalued (see the so-called paradigmatic mode of thought; Bruner, 1991).

43 The question arises about the extent to which the counselor should leave the narrative to its course and to what extent he or she should enable people with low inclination to tell more narrative stories. We know from research that motivating should concentrate on the person (e.g., preparing to understand the narrative approach) and, if feasible, focus less on the external circumstances, such as the topic, sequence, or even the type of narrative stimuli used. The motivating process could include the initial phase of the interview (e.g., explanation of expectations) and will perhaps require some effort in the midst of the storytelling (e.g., by hinting at elements of the narrative, the world presented, the characters and their fates or additional prompts based on questions like “what?” “where?” “when?” or “who?”). However, while being too actively involved in the client’s storytelling, the counselor should be aware of the limited additional psychological value of self-narrative, as the free and spontaneous narrative structuring has been disturbed.

Limitations and Future Directions

44 When considering the results of this study, we have to remember that a small set of methods (instructions) was tested, and the narratives were examined only from a micro-analytical perspective and on a lexical level. The instructions elicited self-narratives that were similar according to the level of utterance narrativity. However, the significant limitation of this research is the fact that it is not known whether instruction usefulness is high, as there is no empirical point of reference that would allow that to be established now. We rely here on the rational expectations, derived from knowledge of research interviews and counseling, that people respond following the contract and react according to what they are asked about, at least at a task-based level. Other methods (instructions) used in interviews should be compared in future studies to contribute to evidence-based assessment and practice standards.

45 Moreover, the presented results are restricted to the first narrative in response to a narrative stimulus. The lack of control for the length of interview time is also a limitation, especially if we would draw conclusions about the overall usefulness of the narrative methods. The analysis of narrativity and other properties of response to the instruction should also be assessed on the macro-analytic level in future research.

46 A significant limitation of the study is that it was conducted under laboratory conditions by researchers trained in a standardized research interview. The contact (rapport) with the subjects was short, and their involvement in the research was not preceded by the need to get help in self-recognized difficulties. Subsequent research could take into account the more natural circumstances of the study, increasing its ecological validity. This would allow more to be said not only about the reaction to a particular instruction but also about the broader impact of the instruction, including the quality of the relationship and psychological rapport. Qualitative systematic analyses of the experiences of the interviewees and counselors would also bring a more realistic picture. Other personality features (besides self-narrative inclination) are therefore worth exploring, as well as other relational factors that play an important, or perhaps vital, role in obtaining autobiographical narrative data.

Conclusions

47 The narrativity of utterances measured micro-analytically on the lexical level and obtained from the participants in psychological qualitative research and counseling practice remains independent from external factors (sequence, topic, instruction). Given the level of narrativity, these methods are close to each other. It is worth noting, however, that narrativity appears to be significantly influenced by individual differences, like self-narrative inclination. Research suggests that we cannot recommend any of the tested instructions, but neither can we necessarily consider them equivalent. It is worth keeping an eye on personal factors that can change the way the story is told in interviews, thus impacting the counseling practice.