Articles

Could the Tree of Life Model Be a Useful Approach for UK Mental Health Contexts?

A Review of the Literature

Some suggest the ethos of the Tree of Life (ToL) group aligns with the concept of “personal-recovery” promoted in mental health policy. Thus, it is claimed that the group could be a useful approach within UK mental health services. This review collated 14 papers to explore whether existing literature regarding the ToL group supports this assertion. The papers were synthesized using the thematic analysis method and three broad themes were identified, which support the argument for its utility within services. These were recovery-aligned themes, the inclusivity of the model, and group processes relevant to mental health contexts. The papers are critically appraised, key concerns regarding the wider literature discussed, and clinical implications summarized.

1 Narratives regarding psychological distress have changed in recent years away from “disorder narratives” focused on lifelong disability, decline and the need to “cure” or “remove” symptoms (Harding, Zubin, & Strauss, 1987; Ridgway, 2001). Narratives now acknowledge “personal-recovery,” where individuals can live meaningful lives in the presence of ongoing distress (Slade et al., 2012). Although recovery from mental health difficulties is defined as a unique and personal experience, Leamy et al. (2011) found by reviewing over a thousand studies that many processes were common between people. These included connectedness, hope, renewed identity, meaning-making and empowerment, all of which have come to dominate mental health legislation. Services now emphasize the importance of those key elements in recovery from mental ill health (Slade et al., 2014). However, it has been acknowledged that this transformation in policy has been difficult to translate into practice. Some have highlighted the lack of recovery-focused care in mental health services and have criticized the “tokenistic” approach to recovery that often exists in inpatient wards (Slade et al., 2014). The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health (2016) subsequently recommended that services should increase recovery focused activity in mental health settings (Mental Health Taskforce, 2016; NHS England, 2014).

The Narrative Approach

2 The word “narrative” refers to the emphasis placed upon the stories of people’s lives and the differences that can be made through the telling and retelling of these stories (White & Epston, 1990). When a context is problem- or deficit-focused, as some suggest mental health services are, the stories people tell about themselves come to reflect these discourses and become problem-saturated (Payne, 2006). Narrative approaches intend to reconnect the person with parts of their life that are not dominated by the problem to create an “alternative story” filled with strengths and resilience rather than problems and deficits (Morgan, 2000).

3 Some have suggested that the strength and re-storying focus of the narrative approach, as well as its focus on personal understandings and responses to mental health difficulties, aligns with the mental health recovery movement (Fraser et al., 2018; Nurser, 2017). In keeping with this, the British Psychological Society (BPS) recommended further investigation of one narrative methodology, Collective Narrative Practice, to improve recovery-aligned activities in UK mental health contexts (BPS, 2012; DoH, 2001).

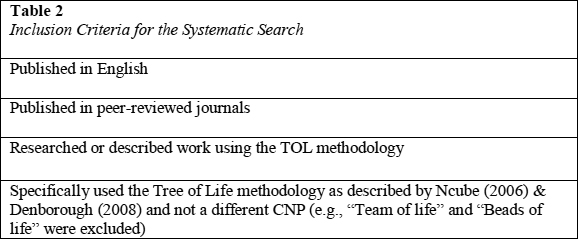

4 The phrase “Collective Narrative Practice” (CNP) describes a collection of group methodologies based on the narrative approach. They were developed to respond to communities who have experienced significant distress and for contexts where traditional therapy may not be culturally resonant or possible (Denborough, 2012). This review focuses on the first such methodology to be developed, called the Tree of Life group (ToL). The core elements of the methodology include helping people to find a “safe place to stand” by identifying the rich mix of skills and strengths within a community alongside their hopes and dreams for the future, and then exploring the multiple ways that communities have responded individually, and collectively, to hardship, so as to create an alternative story of coping and resilience (Denborough, 2012). A summary of the ToL group and the narrative intentions of the group can be found in Table 1 below but are detailed in full in Ncube’s (2006) paper. A general overview of the history of CNPs can be found in Denborough’s article (2012).

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1

5 It is well documented that, in the current NHS climate, there is a shortfall in psychological therapy provision (Hellider, 2009; Paturel, 2012). Therefore, narrative group therapy, such as CNPs, are an effective way to increase access to psychological therapies in a cost-effective manner whilst providing additional therapeutic benefits of social cohesion and universality (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005). In addition, by running a group with an ethos that moves away from the idea of “cure” (as in clinical recovery), services may be able to redirect resources into what is important to service users; this includes creating a meaningful life in the presence of ongoing psychological distress. With this in mind, service users could be discharged earlier from services, with support focusing on managing rather than removing symptoms. This change of focus in mental health care could ultimately reduce inpatient admissions and, in turn, lower costs.

The Current Review

6 The narrative approach is grounded in post-structuralism and social constructionism (White, 1997). Thus, narrative literature often moves away from structuralist research paradigms towards a rich network of “non-research” (Greenhalgh, 2014, pp. 30, 170), practicebased evidence. However, due to dominant discourses in health care of evidenced-based practice being the gold standard, this is often not seen as “credible knowledge,” and the utility of narrative approaches may often be left out of empirical reviews (Neimeyer, 1993; Nolte, et al., 2016; Roy-Chowdhury, 2003). To exclude this rich descriptive information on account of what is deemed acceptable knowledge by dominant power structures (Smith, 1997) would create a “thin” story of the ToL group. It may risk excluding many helpful stories about the identity of the ToL model that may be too complex to fit within traditional research paradigms or may not align with traditional empirical measures (Greenhalgh, 2014, p. 235; Roy-Chowdhury, 2003; Wellman et al., 2016). Clinicians have acknowledged the benefits of including practice-based evidence within reviews, as it helps to bridge the research–practice gap that often exists in healthcare settings (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006; Greenhalgh, et al., 2018). Therefore, this review synthesizes research and non-research literature, including papers that are not described as research papers, do not present aims, a method or clearly report research outcomes, but instead describe an application of the ToL group. The term “descriptive papers” is adopted for the purpose of this review.

Aims

7 To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time that a broad selection of literature on the ToL group has been brought together and synthesized whilst critically appraising the available evidence and exploring whether it could be a useful model for UK mental health contexts. Descriptive articles are included in the review to explore the stories told about the ToL group in a “rich” way.

8 This review employed a systematic search strategy to answer the following question: Could the ToL model be a useful intervention for UK mental health contexts (referred to as “mental health contexts” hereafter)?

Method: Literature Search

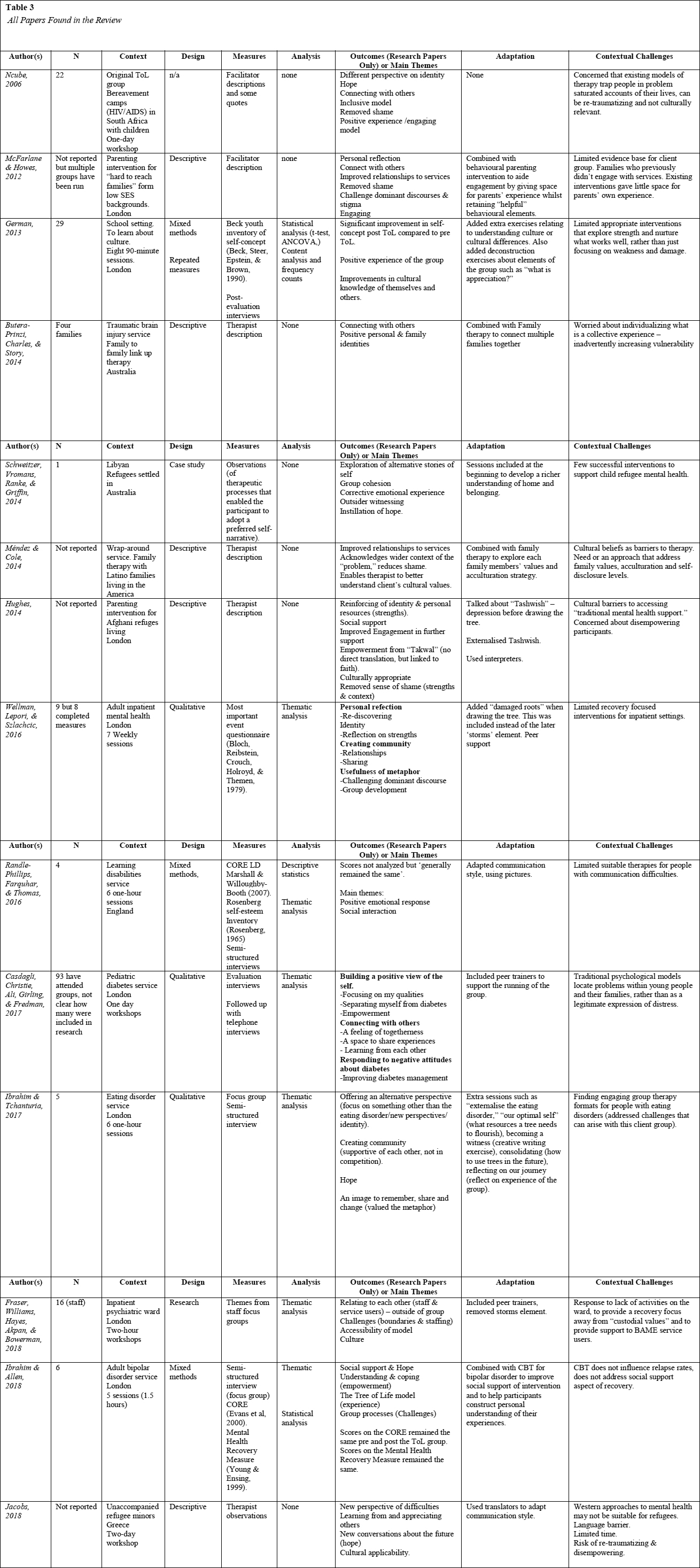

9 Three electronic databases were searched on 15 August 2019. Searches were conducted using PsychINFO, SAGE, and Wiley Online Library. As this review does not exclude descriptive papers, literature searches had to continue beyond standard database searches. The International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work was later searched using the terms “Tree of Life” and then “Collective Narrative Practice,” as this journal holds multiple accounts written about narrative work. Similarly, a wider search was conducted using Google, Google Scholar, and publications such as Context and The Clinical Psychology Forum to ensure as many descriptive articles as possible were included. Several clinicians who are embedded within ToL networks, including a key figure in creating the ToL group, were approached for any additional papers that may have been missed, and the authors posted a question on a specific ToL social media page regarding additional papers. A further six papers were found and examination of the reference section of all papers revealed four more relevant papers. Table 2 outlines the inclusion criteria for papers identified in the literature search.

Literature Review

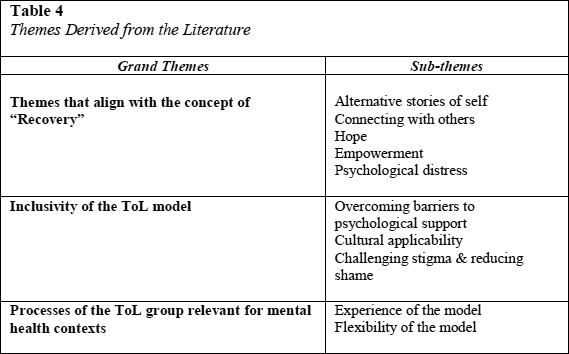

Structure

10 What follows is a narrative literature review that is structured according to themes drawn out from the literature using a thematic analysis method (Ferrari, 2015; Thomas & Harden, 2008). Individual papers were analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Firstly, the descriptive papers were read in full and then content from the articles was organized into codes so that themes could be explored across papers, forming part of the synthesis. Overarching patterns or divergences between themes were identified so that initial codes could be organized into grand themes. Table 3, below, shows all the papers included in the review.

Thematic Summary

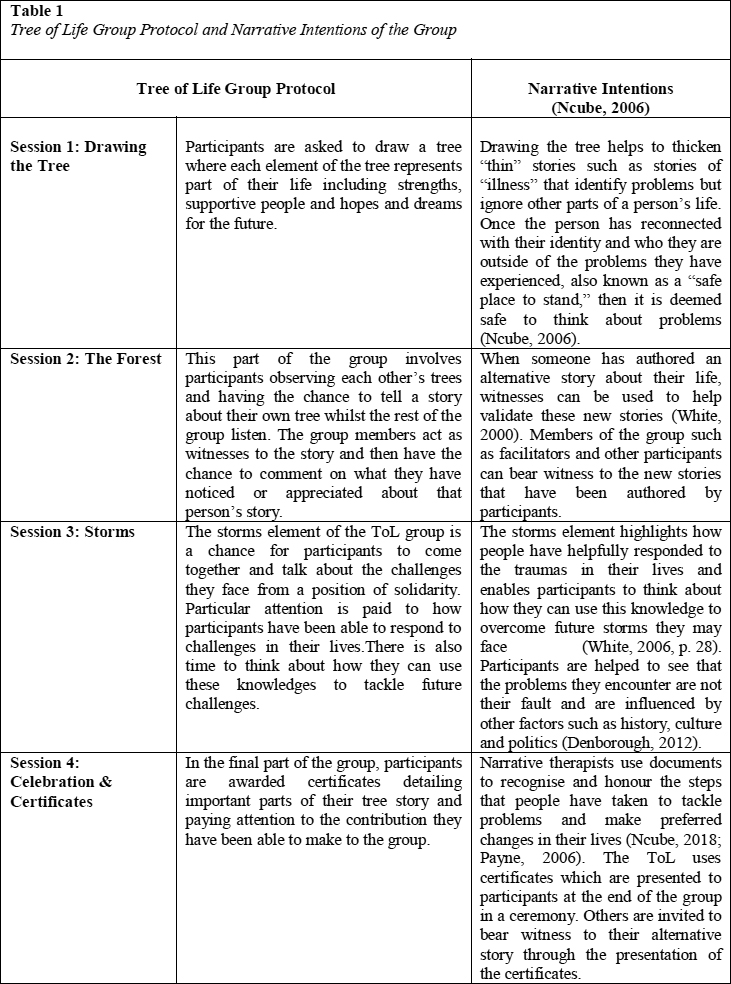

11 Three overarching themes were derived from the literature that applied to the utility of the ToL group in mental health contexts and are summarized in Table 4:

Themes that Align with Stages of Personal Recovery

12 Thirteen papers were identified as belonging to at least one theme that aligns with the concept of personal recovery from mental health difficulties as described by Leamy et al. (2011).

13 Alternative Stories of Self. A dominant theme across six research and five descriptive papers was the idea that the ToL group creates an alternative narrative for individuals away from problem- saturated descriptions of their lives (Butera-Prinzi et al., 2014; Casdagli et al., 2017; Fraser et al., 2018; German, 2013; Hughes, 2014; Ibrahim & Tchanturia, 2017; Jacobs, 2018; Ncube, 2006; Randle-Phillips et al., 2016; Schweitzer et al., 2014; Wellman et al., 2016).

14 In the papers that used the ToL in health contexts, the model helped participants look beyond seeing themselves solely in terms of their illness (Casdagli et al., 2017; Fraser et al., 2018; Ibrahim & Tchanturia, 2017; Wellman et al., 2016). For example, in Casdagli et al.’s (2017) group for young people with diabetes, the participants felt that the ToL model helped them to see diabetes as part of themselves rather than their full identity: “I often feel like I am just a diabetic … but this has helped me realise that there is much more to me” (p. 13).

15 The participants in Casdagli et al.’s (2017) group as well as in two other papers (Ibrahim & Tchanturia, 2017; Schweitzer et al., 2014) specifically mentioned the process of outsider witnessing as an important element of the group that facilitated the development of an alternative, more positive view of the self: “Having the group act as witnesses … helped … strengthen a [positive] self-narrative” (Schweitzer et al., 2014, p. 14).

16 Two papers used questionnaires to quantitatively explore the effect of the ToL group on participants’ self-esteem and self-concept; the results revealed a split in the data (German, 2013; Randle-Phillips et al., 2016). In the context of a ToL school-based group, German (2013) reported a statistically significant increase in post-scores compared to prescores on the Beck Self Concept Inventory (Beck et al., 1990). The study reported a large effect size and controlled for extraneous variables such as gender, ethnicity, and age, showing a robust improvement in self-concept after the ToL group. In contrast, in the context of a group for people with learning disabilities, Randle-Phillips et al. (2016) found that participants’ self-esteem decreased between pre- and post-measures. However, the authors did not employ statistical analysis of these scores, so it is not clear whether this was a significant decrease. Moreover, the self-esteem measure (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; Rosenberg, 1965) was administered to individuals with a learning disability despite not being validated for this population, which could have caused issues in the validity of the findings from this measure.

17 It is also important to note here the difference in the measures between the who am I/identity element of self (self-concept: German 2013) including future goals, strengths, beliefs, and values, compared with the how confident am I in myself element of self (self-esteem: Randle-Phillips et al., 2016). As mentioned above, the ToL model is aligned with and intends to develop the alternative identity or self-concept (who am I) . It is not denied that the two may be inextricably linked, but when someone has been exposed to an alternative version of themselves or their identity, it may take some time to develop confidence in this new-found story. Thus, the self-esteem scale may not have been a valid measure even if it had been used correctly, due to the mismatch between what it intends to measure versus what the ToL intends to do.

18 Connecting with Others. A key theme reported in seven research papers was the idea of being able to connect with others or find social support and emotional containment from others (Casdagli et al., 2017; German, 2013; Ibrahim & Allen, 2018; Ibrahim & Tchanturia, 2017; Randle-Phillips et al., 2016; Schweitzer et al., 2014; Wellman et al., 2016): “I like the way it brought everyone together to actually work with each other … I learned a lot” (German, 2013, p. 86). This theme was also present across five descriptive papers and connecting with others in the group enabled members to have their experiences heard and put into context of others’ experiences (Butera‐Prinzi et al., 2014; Hughes, 2014; Jacobs, 2018; McFarlane & Howes, 2012; Ncube, 2006): “I know I’m not alone” (Hughes, 2014, p. 149).

19 In Ncube’s (2006) group for bereaved children, reference was made specifically to the ToL facilitating participants to “re-member” (see Table 1 for definition) and purposely reconnect with people, past and present, who have been important in the person’s life. For example: “There are many people who have done a lot for us in our lives but sometimes we forget this and rarely acknowledge them” (Ncube, 2006, p. 16).

20 Three papers reported that this feeling of connecting with others, or community, transferred to the context outside of the group (Butera-Prinzi et al., 2014; Fraser et al., 2018; German, 2013; Wellman et al., 2016). For example, in the paper that explored staff perceptions of the ToL group in an inpatient psychiatric ward, connecting with others in the group was said to have helped to improve the ward environment as staff begun to see service users in terms of their identity and not just as patients: “It gives me a good starting point for me to build rapport with them to find out about their life” (Fraser et al., 2018, p. 10).

21 However, the results from Fraser et al. (2018) should be interpreted with caution as the paper did very little to describe the method of the research, including how participants were chosen, what questions were asked of participants, who held the interviews, and how the themes were derived. It is noted that the authors of the paper are heavily involved in the running of the ToL groups and therefore participants may have felt compelled to respond positively. Furthermore, there was no longer term follow up after the group, so it is not known whether these gains were maintained over time.

22 Engendering Hope. The theme of hope was well represented in groups run in mental health contexts and was identified in three research papers (Ibrahim & Allen, 2018; Ibrahim & Tchanturia, 2017; Wellman et al., 2016). Identifying a renewed attitude towards the future was reflected metaphorically with the idea of moving away from “doom and gloom”— away from darkness towards light (Wellman et al., 2016). For example, “It [was not] all being about a dark path” (Ibrahim & Tchanturia, 2017, p. 8); “I can see a light at the end of the tunnel” (Ibrahim & Allen, 2018, p. 17).

23 This theme was also replicated in descriptive papers with groups run to support mental health reflecting the strongest representation of hope where participants reported having renewed hope or faith that could help them to survive the storms they were facing and “look forward to living each day” (Butera‐Prinzi et al, 2014; Hughes, 2014; Jacobs, 2018; Ncube, 2006).

24 Empowerment. The theme of empowerment was present in two descriptive papers and one research paper, and although not as commonly reported as hope, was closely linked to the concept of hope in other papers. Participants reported feeling able to overcome future challenges. In the context of parenting support for “hard to reach” or refugee mothers, parents reported having new ideas or a feeling of strength within themselves (Hughes, 2014; McFarlane & Howes, 2012): “I feel stronger now as a parent” (McFarlane & Howes, 2012, p. 24). Some papers also reported that participants had specifically learnt new ideas, from themselves or from others, to help them feel able to tackle and overcome problems in their lives (Casdagli et al., 2017).

25 Tree of Life and Psychological Distress. Two quantitative papers explored the impact of the ToL group on psychological distress using the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (Ibrahim & Allen, 2018; Randle-Phillips et al., 2016). The studies found that the scores remained the same with no statistically significant reductions in distress. However, both studies had small numbers of participants to be employing statistical analysis (four and six respectively) and no consideration was given to issues of power, which is likely to have rendered the data invalid.

26 In the context of a group for people with bipolar disorder, Ibrahim & Allen (2018) used the Mental Health Recovery Measure to explore if the ToL group had any impact on recovery from psychological distress. Similarly, the measure showed that participants’ feelings of recovery remained the same in all domains on pre- and post-measures. The recovery measure was administered in the final group session and was not followed up; therefore, it is not clear whether the measure may have been impacted by negative or positive feelings regarding the ending of the group. Despite the methodological concerns, the non-significant findings are supported by the absence of an explicit theme relating to reductions in psychological distress in any of the descriptive or qualitative papers.

Inclusiveness of the ToL Model

27 A theme evident across all 14 papers was authors’ description of the inclusiveness, in some way, of the Tree of Life model.

28 Overcoming Barriers to Psychological Support. Every paper found in the literature referred to the ability of the ToL model to overcome barriers to providing psychological support, either related to the participants’ demographics or the setting in which the therapy was delivered. Many papers identified participants who may be deemed difficult to engage in other types of psychological therapy, including those from non-Western cultures, those in mental health crises, or individuals with a learning disability (Fraser et al, 2018; Jacobs, 2018; Randle-Phillips et al., 2016): “This approach may be helpful for people who had found it difficult to engage in psychological therapy in the past” (Randle-Phillips et al,, 2016, p. 3).

29 An example of this finding was identified in the four papers in the literature that referred to using the ToL model with refugees (Hughes, 2014; Jacobs, 2018; McFarlane & Howes, 2012; Schweitzer et al., 2014). In the context of running a ToL group in a refugee camp in Greece, Jacobs (2018) explained that traditional models of psychological support may disempower refugees by their focus on problems, and that the ToL model was one way to overcome this tendency. Jacobs (2018) also highlighted how Western models of therapy are unusual, or stigmatizing, to refugees, which may stop them accessing traditional types of mental health support: “Connecting with refugees is quite a challenge, as they usually come from countries that do not facilitate mental health support” (Jacobs, 2018, p. 281).

30 Despite all authors referring to the ToL group as an inclusive model, none of the papers investigated inclusivity from the perspective of participants in the groups. It is possible that this observation about the inclusive nature of the ToL model may be a biased opinion that may be evidenced through those who have chosen to participate in the group, rather than those who declined to be involved.

31 All other authors acknowledged that the ToL group could help overcome contextual challenges to providing traditional models of psychological support (detailed in Table 3). For Jacobs (2018), this included working with “limited time” and resources (p. 282), but for others included concerns about “the potential to disempower and silence people [with] … psychological interventions” (Hughes, 2014, p. 140) by focusing on problems-saturated descriptions of people’s lives (Fraser et al., 2018; Hughes 2014; Wellman et al., 2016), or recognizing the limited evidence base for parenting interventions (McFarlane & Howes, 2012).

32 Cultural Applicability. All papers that used the ToL with refugees or with any participants from a non-Western culture referred to cultural applicability as a key reason for using the ToL model (German, 2013; Hughes, 2014; Jacobs, 2018; Méndez & Cole, 2014; Schweitzer et al., 2014). There was emphasis on the ToL model being able to incorporate different understandings of psychological distress that may not fit within other models of mental health care due to their Western values: “Western mental health service impose models of mental health care that do not fit [with non-Western cultures]” (Hughes, 2014, p. 141).

33 Méndez and Cole (2014) found that using the ToL to learn about culture between therapist and client helped to improve relationships in the therapy, but also noticed that it improved engagement in other services, as families felt they were better understood by therapists. The ability of the ToL group to improve engagement in services was additionally noted in two other papers (Hughes, 2014; McFarlane & Howes, 2012): “The Tree of Life activity can be used as an important tool in gathering cultural values ... to provide culturally sensible services” (Méndez & Cole, 2014, p. 219).

34 German (2013) specifically focused on the ability of the ToL model to help others learn about different cultures in the context of reducing racism in school children. German used quantitative measures to explore the effect of the ToL group on cultural understanding and awareness. Statistical analysis of the scores revealed that there were significant increases in cultural understanding after attending the ToL group compared to cultural understanding before the ToL group. However, it must be noted that the ToL model was used among other exercises to help the children understand their own and other cultures, such as conversations with parents and show- and-tell exercises in the classroom; therefore, it is not clear how much the increase in cultural understanding was due to the ToL model or the other classroom exercises.

35 Reducing Stigma and Shame. Four research and four descriptive papers highlighted the ability of the ToL model to deconstruct, challenge, or acknowledge wider societal discourses that contributed to problem narratives, such as the stigma and labels applied to people with learning disabilities or the wider systemic issues parents faced including poverty, deprivation, and past abuse or negative attitudes surrounding diabetes (Casdagli et al., 2017; German, 2013; Hughes, 2014; Jacobs, 2018; Méndez & Cole, 2014; McFarlane & Howes, 2012; Randle-Phillips et al., 2016; Schweitzer et al., 2014):“It helped me challenge some of the misconceptions” (Ibrahim & Allen, 2018, p. 7).

36 Interestingly, in four descriptive papers, authors reported that participants seemed able to talk about their problems “with seemingly no shame” (Ncube, 2006, p. 13) because the wider context of their difficulties had been acknowledged. For example, in the context of a parenting intervention, the authors stated that parents were able to speak about the challenges of parenting and were receptive to some of the ways to overcome them, as “they felt less blamed” (McFarlane & Howes, 2012, p. 23). Others attributed this reduction in shame to the focus of the group in speaking with solidarity rather than from an individualistic perspective (Ncube, 2006): “It proved not to be difficult to talk collectively”; “The solidarity in their responses was even bigger” (Jacobs, 2018, p. 289)

Processes of the ToL Group Relevant to Mental Health Contexts

37 Flexibility of the ToL Model. There was a theme across all papers, apart from the original paper describing the Tol methodology (Ncube, 2006), that the ToL model could be adapted in some way, to suit the context or the need of the client group. The adaptations (detailed in Table 3) were either superficial, where Ncube’s (2006) original methodology was maintained, or profound, where adaptations meant the methodology was changed in some way.

38 The superficial adaptations involved; modifying communication styles to suit the needs of participants (Hughes, 2014; Jacobs, 2018; Randle-Phillips et al., 2016), the addition of extra sessions to consolidate learning (Ibrahim & Tchanturia, 2017), or the addition of service-user peer trainers to either run, or support the running of, ToL groups (Casdagli et al., 2017; Fraser et al., 2018). The profound adaptations included three papers that removed the “storms” element of the group (Fraser et al., 2018; German, 2013; Wellman et al., 2016) and four papers that made an adaptation to the group which meant “a safe place to stand” was not reached before moving on to talk about problems (German, 2013; Hughes, 2014; Schweitzer et al., 2014; Wellman et al., 2016). Moving away from the original protocol of the group means that the researchers are not investigating the Tree of Life model itself, but rather an adaptation of it, which may call into question the validity of the data from these studies in reference to the utility of the full Tree of Life model. Moreover, Ncube (2018) advises against these kinds of adaptations as they reinforce a problem- saturated story over the subjugated alternative story of strength and resilience that the group intends to bring forward (Ncube, 2018).

39 The ToL was also combined with other models of therapy to provide a “holistic” intervention (Butera-Prinzi et al., 2014; Ibrahim & Allen, 2018; McFarlane & Howes, 2012; Méndez & Cole, 2014). For example, in the context of a parenting intervention, the ToL was combined with traditional behavioural parenting interventions to “maintain parents’ interest” and to “give an alternative voice to those who have been oppressed by dominant narratives” and create “an atmosphere of reflectiveness missing in traditional behavioural approaches” (McFarlane & Howes, 2012, pp. 22–23).

40 Experience of the Model. Six research papers made reference to participants’ enjoyment of the model. Two quantitative analyses revealed that participants reported enjoying or experiencing positive emotions in the ToL group (German, 2013; Randle-Philips et al., 2016). In the context of a school intervention, all participants rated the group 5 out of 10 or above (10 being enjoyable), with more than half of participants rating the group 10 out of 10 (German, 2013): “I really enjoyed it .... I liked creating the tree and that you could do it in your own way” (German, 2013, p. 86).

41 Three qualitative papers referred specifically to the usefulness of the tree metaphor to either contain emotion (Wellman et al., 2016), make the group easy to remember (Ibrahim & Tchanturia, 2017), or provide a good structure (Ibrahim & Allen, 2018): “I will definitely remember the Tree of life because it is so visual” (Ibrahim & Tchanturia, 2017, p. 7).

42 Four of the qualitative papers identified themes that highlighted challenges noted by participants or facilitators—specifically, challenges regarding the groups’ attendees: participants not attending, loud participants, participants wanting to swap partners (German, 2013; Ibrahim & Allen, 2018; Randle-Phillips et al., 2016), or participants not wanting ward staff to attend (Wellman et al., 2016). In the descriptive paper that explored staff perceptions of the ToL group, staff reported finding it challenging to know how much personal information to share with participants (Fraser et al., 2018).

43 The theme of experience was represented in descriptive papers through facilitator reports of participants enjoyment of the model, reflected by authors reporting on the “engaging” nature of the model and describing how much participants were talking in groups or getting involved with the group activities (Hughes, 2014; Jacobs, 2018; McFarlane & Howes, 2012; Méndez & Cole, 2014; Ncube, 2006): “All boys agreed to come back,” reported Jacobs (2018, p. 289); Ncube (2006) spoke of “the enthusiasm the children were demonstrating” (p. 9).

44 In the descriptive papers, challenges were often not reported, which raises questions as to whether there is a positive publication bias to the running of groups that were successful, or whether authors are leaving out challenges from reflective accounts which once again would mean a positive bias in reporting on the ToL group. Even in research papers, there tended to be a positive publication bias where challenges or limitations of the model were often left out of reports.

Discussion

45 This review aimed to explore whether the ToL group could be a useful model for mental health contexts. Three key themes were identified in the literature that helped to answer this question: themes that align with the concept of recovery, the inclusivity of the ToL model, and processes of the ToL group relevant for mental health contexts.

46 This review supports claims made by professionals who have used the ToL model, that the model aligns with the concept of personal recovery from mental health difficulties (Fraser et al., 2018, Ibrahim & Allen, 2018; Wellman et al., 2016). Many recovery processes featured heavily in the ToL literature (see Table 4), with 13 papers identifying at least one process as an important outcome of the ToL group. In addition, the literature showed that many of the key intentions of the group documented by Ncube (2006) and Denborough (2012) were well represented within the themes found, suggesting that the ToL is achieving what it sets out to achieve.

47 The review highlighted the ability of the ToL model to connect people and create a supportive environment. The finding that this connectivity transferred to contexts outside of the group is important, as it has been shown that better inpatient experiences are linked to faster recovery rates and reduced subsequent admissions (Mullen, 2009). On a wider note, it appeared that the ToL model was able to challenge longstanding institutional “disorder” narratives by helping staff to see service users through their identity, rather than their diagnosis.

48 Despite the ToL model’s alignment with the concept of recovery, there were no significant changes observed on measures of psychological distress. At first glance, this may indicate that it may not be a useful model for a mental health context, as the focus of these contexts traditionally is to reduce psychological distress. However, as mentioned earlier, personal recovery moves away from “curing” distress towards understanding difficulties and living a meaningful life in the presence of ongoing symptoms. Not finding any significant changes in psychological distress may reflect the measures’ focus on observing a reduction of symptoms (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2016) which is not the intention of the ToL group. Rather the ToL group could be said to focus on changing the relationship with the problem through re-storying (Hughes, 2014).

49 This review highlighted the inclusivity of the ToL model, which was described in every paper as one of the main motivations for using it. This is relevant due to the increasingly diverse contexts in which psychological interventions are being sought and delivered, combined with the increasingly diverse populations requiring psychological support in the UK. A recent report revealed that many people, especially marginalized populations, feel excluded from mental health services due to their lack of focus on diversity (London Assembly, 2018).

50 This review also highlighted that the ToL appears a useful model to begin to challenge and acknowledge some of the wider influences and discourses that contribute to people’s experiences of problems, something which many feel is often ignored in some models of therapy that focus on the individual (McGrath, Griffin, & Mundy, 2015; White, 1997). Some authors felt that this acknowledgement of wider contextual factors and stigma helped to reduce shame around addressing different problems (Jacobs, 2018; McFarlane & Howes, 2012; Ncube, 2006). It is widely acknowledged that shame is an emotion linked to many different mental health problems, but also an emotion that can contribute to further difficulties and that can prevent help-seeking (Miller, 1996; Rüsch et al., 2014).

Overall Critique of the Literature for the ToL Group

51 There was a general paucity of published research articles on the ToL group, considering it has been used in clinical contexts since 2006. Although some possible reasons for this have been considered, there are many methods that would be more aligned with the narrative approach, including case study designs or narrative analysis. Use of such approaches would help increase the number of research papers written on the ToL group, helping to secure its use in evidence-based mental health contexts.

52 There were several issues of bias in the literature. First, there tended to be a largely positive reporting of experiences of the ToL group with less attention paid to challenges of running the group. There generally appeared a lack of reflexivity in the reporting of descriptive articles, which meant that bias in the reporting of running groups was not considered. Second, the issue of researcher bias was not fully considered by all authors. Of particular concern was that all qualitative interviews were carried out by facilitators of the groups, which as previously mentioned may have made it difficult for participants to speak honestly about their experiences of the groups (Collins, Shattell, & Thomas, 2005).

53 The use of mixed methods was a particular area of downfall as these papers often had a very small number of participants which may be acceptable in collecting qualitative data, but is not sufficient for quantitative analysis.

Clinical Implications

54 Mental health services may benefit from using the ToL model for several reasons: first, to facilitate engagement in services by improving the availability of culturally diverse and strengths-focused approaches. Second, there is an increasing call for approaches that are recovery-based. The emerging positive impact of using service-user facilitators to run the ToL group would suggest that more services should explore the use of peer support when considering running a ToL group. This fits with global policies that promote the use of experts by experience in all different areas relating to psychosocial wellbeing. It appears to have benefits for both service users and peer trainers.

55 It is recommended that clinicians, where possible, follow the original methodology and intentions of the group and avoid making profound adaptations that may displace the group from its original narrative intentions, until more is known about removing key elements of the group. Removing the storms element may reinforce dominant ideas that “expert knowledge” in mental health settings is more powerful, or important, than participants’ own experience, which is not the intention of the group. Ncube (2018) acknowledges that the ToL group can be run by anyone from any profession but highlights the importance of receiving the relevant training to ensure that facilitators are aware of the theoretical intentions of the group. It is recommended that clinicians hoping to run a ToL group for the first time attend training on the ToL group (PHOLA offer a certified Tree of Life training but other trainings are available through different mental health trusts).

Limitations of the Review

56 Leamy et al.’s (2011) model of recovery features heavily throughout the review and some may suggest the themes found in the literature were moulded to fit recovery processes. However, this framework was used to guide the reporting of the themes, after the initial analysis had been completed. Bracketing measures were taken to reduce chances of bias in moulding themes to fit with the model.

57 Additionally, although clear reasons have been presented for including descriptive papers, there are risks that conclusions drawn from the literature may hold a positive bias. This is because in some papers formal research protocols were not implemented and the literature focuses on the author’s account of the group with little consideration of the issue of bias or further exploration of participants’ views.

Conclusions

58 This is the first review to consider a wide range of literature on the ToL group. Both research and descriptive papers (n=14) were reviewed to answer the question: Could the ToL group be useful in mental health contexts? Findings were organized under three broad themes: recovery aligned outcomes, inclusivity of the ToL model, and processes of the ToL group relevant to mental health contexts. A key finding of the review was that the ToL model is helpful for those where other models may not be applicable either due to their Westernized or problem-focused approach to distress. Thus, it is a model that can be utilized in the ever-expanding contexts requiring formal psychosocial support and is relevant in today’s mental health contexts due to its alignment with elements of recovery models. It is suggested that clinicians should be cautious when making adaptations to the group to avoid distancing it from the theoretical intentions and that the use of peer trainers could provide benefits both to the participants of the group and the service user experts themselves.